Abstract

Multiple myeloma (MM) progression is driven by immune dysregulation within the tumor microenvironment (TME). However, myeloma-intrinsic mechanisms underlying immune dysfunction remain poorly defined, and current immunotherapies show limited efficacy. Using RNA-seq data from 859 MM patients (MMRF-CoMMpass), we integrated xCELL, CIBERSORT, and ESTIMATE algorithms to deconvolute immune-stromal dynamics. Consensus clustering identified immune subtypes, followed by differential gene analysis and LASSO-Cox regression to construct a prognostic model validated in an independent cohort (GSE19784, N = 328). Immune Subtype Classification: Two subgroups emerged: Multiple myeloma-associated immune-related cluster 1 (N = 482): Immune-dysfunctional TME with Th2 cell enrichment, preadipocyte accumulation, and CXCL family suppression, linked to poor survival (P < 0.001). Multiple myeloma-associated immune-related cluster 2 (N = 377): Immune-active TME with cytotoxic CD8 + T/NK cell infiltration and favorable outcomes. Prognostic Gene Signature: Ten immune-related genes (UBE2T, E2F2, EXO1, SH2D2A, DRP2, WNT9A, SHROOM3, TMC8, CDCA7, and GPR132) predicted survival (The One-year AUC = 0.682 and The Over 5-years AUC = 0.714). We define a myeloma-intrinsic immune classification system and a 10-gene prognostic index, offering a framework for risk-stratified immunotherapy. Integration with flow cytometry could optimize precision treatment in MM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

MM is a malignant hematologic tumor, ranking as the second most common condition in the field of hematology-oncology. It is characterized by the uncontrolled proliferation of abnormal plasma cells within the germinal center. The onset of multiple myeloma tends to be subtle, giving rise to clinical manifestations such as bone deterioration, kidney impairment, and the presence of monoclonal gammopathy1. The clinical spectrum of plasma cell proliferation encompasses benign plasma cell expansion, known as monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), progressing further to a premalignant state termed smoldering MM (SMM)2. Additionally, MM can progress to an extramedullary stage, with some cases transitioning to plasma cell leukemia (PCL)3,4,5,6,7. Despite considerable advancements in therapy over the past decade, MM remains an incurable ailment8.

Genetic modifications within malignant plasma cells exert a pivotal influence on the clinical trajectory of MM. In addition to well-documented genetic anomalies like del(17p) and t(4;14), various cytogenetic factors contribute to the development of active MM, including del(1p32), gain(1q), and trisomy1. Intriguingly, these alterations frequently occur within transformed plasma cell clones during the MGUS and SMM stages, suggesting an intricate interplay between quiescence and the progression to premalignancy, influenced by external factors2. In this context, the human body’s immune system assumes a substantial role in maintaining this equilibrium. Clinical investigations have revealed that MM cells exhibit many of the physiological traits of normal human plasma cells. Yet, they also depend on the bone marrow microenvironment for their survival and proliferation, eventually establishing a form of immune evasion9. This allows them to break free from the confines of the bone marrow and disseminate throughout other body tissues, clinically presenting as plasmacytomas10.

It is well-established that the bone marrow microenvironment plays a pivotal role in governing the initiation of MGUS-MM and the progression of MM. Smoldering monoclonal gammopathy represents an intermediate stage in the evolution of multiple myeloma. This phase was first identified in 1980, characterized by a serum M protein concentration exceeding 3 g/dL and a bone marrow plasma cell (BMPC) percentage surpassing 10%6. However, investigations have revealed that individuals with smoldering monoclonal gammopathy often exhibit cytogenetic diversity, including abnormalities such as t(4;14), del(13q), gain(1q), and del(17p)11. Recent clinical studies have demonstrated that immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs) like Lenalidomide, when administered during the early stages of high-risk smoldering multiple myeloma, can delay the transition to symptomatic multiple myeloma12. This underscores the role of the bone marrow microenvironment in influencing the progression of multiple myeloma following immunomodulatory drug treatment. It is disheartening to note that patients at advanced stages have a median overall survival (OS) of less than six months. Both EMM and PCL represent malignant plasma cell variants that persistently exploit the bone marrow microenvironment, eventually disseminating throughout the body13. The tumor immunological microenvironment comprises cellular clusters, including immune-competent helper cells, located around tumor cells within human tumor tissues. These cell clusters regulate tumor cell growth and proliferation through intercellular interactions and molecular communication14. Most of these clusters consist of helper cells and T cells. Notably, the microenvironment in the bone marrow differs from that in peripheral lymphoid organs and supports the maturation and differentiation of various lymphocyte types15.

As early as 1889, Stephen Paget introduced the renowned "Seed and Soil" hypothesis, an early conceptual framework illustrating the interaction between tumor cells and the immune microenvironment16. In the context of MM, genomic alterations in plasma cells represent the “seeds” that infiltrate the microenvironment, akin to the “soil” of the bone marrow originally tailored for normal human plasma cells. Within this microenvironment, the infiltrating cells receive crucial survival signals. Some studies have observed minimal discernible distinctions between the malignant plasma cells of MGUS and the “soil” represented by the normal plasma cell-bone marrow microenvironment, which impacts their viability17.

Recent phase III clinical trials have yielded discouraging outcomes regarding the effectiveness of PD-1/PD-L1 in myeloma treatment18,19. This underscores the inadequacy of our current comprehension of the immune mechanisms underlying multiple myeloma, highlighting the need for further research to unravel the intricacies of this disease. Some experts suggest that employing flow cytometry for immunophenotyping myeloma cells and employing targeted precision therapies may offer an optimal approach to treating myeloma9,20,21.

The NGS data contained within the MMRF-CoMMpass database originate from samples collected after bone marrow aspiration in multiple myeloma patients. These samples underwent sequencing following isolation using CD138 + immunomagnetic beads22,23. Regrettably, there is a paucity of literature focusing on this database in the context of TME-related research, owing to inherent limitations in experimental methodologies. We postulate that within the “niches” within myeloma bone marrow, CD138 + myeloma cells likely exert an intrinsic driving force on other immune cells. This presumed "tumor cell driving force" likely involves the expression and regulation of immune-related genes that induce downstream genes, facilitating intercellular crosstalk. At the same time, combining anti-angiogenic therapy with immunotherapy holds promise to reshape the tumor microenvironment and enhance treatment outcomes24. This combination strategy has gained considerable attention due to its potential to overcome the immunosuppressive environment within tumors, thus facilitating a more effective anti-tumor immune response. To bridge this gap, we propose a bioinformatics framework that leverages bulk RNA-seq data from CD138 + myeloma cells to deconvolute immune dysregulation patterns. Unlike conventional methods, our approach identifies tumor-intrinsic gene signatures that predict both immune dysfunction and patient outcomes, enabling scalable clinical translation. This, in turn, culminates in a state of immune suppression or dysfunction within the microenvironment, ultimately leading to tumor cell dominance and unfavorable prognoses. The identification of immune-related prognostic markers for multiple myeloma within this database remains an open question.

In summary, this research aims to advance our comprehension of the molecular mechanisms and the immunological microenvironment of multiple myeloma. It seeks to establish more precise prognostic models, laying a crucial foundation for informed clinical decision-making in the management of multiple myeloma.

Materials and methods

MM data source and data preprocessing

All MMRF-CoMMpass data (N = 859) were freely downloaded from the GitHub repository https://github.com/marziassettinno/MMRFBiolinks, encompassing RNA-seq data (HTSeq counts), single nucleotide variants (SNV), clinical data, and associated phenotypic data22,23. The MM cohort belonged to the MMRF-CoMMpass study and was recruited through the TCGA GDC portal, which also served as the training cohort for our research. They were all normalized using the TPM method25. Another myeloma research cohort was downloaded (GSE19784, N = 328) for external validation (referred to as the validation cohort) in this study from the GEO datasets (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE19784)26. All patient clinical data and related information were rigorously protected to ensure their exclusive use for nonprofit research purposes and to effectively prevent disclosure. The overall research workflow is depicted in Figure S1.

Immune infiltration cells treatment by consensus clustering

To create different subgroups among the various characteristics of immune infiltrating cells in this MM study, the R program Consensus Cluster Plus was employed to identify groupings of different immune infiltrating cell patterns in this dataset using the Pearson correlation coefficient and the “Pam” method, with the permutation parameter set to 1000 to achieve this goal27.

Quantification of the immune infiltration cell condition by xCell algorithm

The xCell algorithm is a novel spillover compensation technique that harmonizes 1872 pure human cell type transcripts from very different tissue cells and separates the cell types. The frequency of tumor matrix cells in this MM study was generated using the xCell R package in the R platform28.

Profiling immune-related algorithms to analyze immune infiltration

We selected xCELL, CIBERSORT, and ESTIMATE based on their complementary strengths in myeloma biology: xCELL: Uniquely includes bone marrow stromal and adipocyte signatures (e.g., preadipocytes), critical for MM microenvironment analysis. CIBERSORT: Optimized for hematopoietic cell deconvolution, outperforming TIMER/EPIC in resolving T/B/NK cell subsets. ESTIMATE: Provides global immune/stromal scores validated in MM clinical cohorts, unlike EPIC’s solid tumor focus.

The CIBERSORT software was employed to transform MM RNA-seq data into fractions representing immune-related cells. Prior to this, the training cohort data underwent standardization as per the requirements of CIBERSORT. CIBERSORT estimates the proportion of 22 immune cell types (e.g., T cells, macrophages) in bulk RNA-seq data using a reference signature matrix (LM22) derived from purified leukocyte subsets. We selected CIBERSORT for its validated accuracy in hematologic malignancies29.

Subsequently, we applied the ESTIMATE calculates stromal and immune scores to quantify tumor microenvironment composition, leveraging gene signatures specific to stromal cells (e.g., fibroblasts) and immune infiltrates. ESTIMATE was prioritized for its proven utility in myeloma studies30.

By computing scores based on gene signatures, the algorithm predicts the levels of infiltrating stromal and immune cells. We conducted single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (SSGSEA) using the GSVA software package in R version 4.0.2, specifying the parameter: method = “ssgsea”31, for the RNA profiles of each sample.

Functional enrichment assay resulted in DE-IRGs

Differential gene expression analysis between the different TME subgroups was conducted using the R package limma, considering genes with |log (fold change) |> 1 and P < 0.05 as differentially expressed genes. Gene Ontology and KEGG enrichment analyses were performed on the ClusterProfiler R package for KEGG pathway enrichment analysis32, and all data visualization charts were created using R. Then we got the differentially expressed immune-related genes (DE-IRGs).

Unifoliate Cox risk regression and LASSO regression to further prognosis

Initially, the prognostic significance of each DE-IRG was assessed. Subsequently, a DE-IRG with a significant prognostic impact was selected, and the LASSO regression method was employed to evaluate its significance. Unifoliate Cox regression analysis was also used to ascertain the relationship between differentially expressed genes of the two MAIC subtypes and survival, with P values < 0.05 indicating genes relevant to survival. Next, we individually incorporated the survival-relevant genes in multiple myeloma into the LASSO analysis. The LASSO method, which performs automatic feature selection, was employed to identify reliable prognostic features. The R software package glmnet was utilized, which applies tenfold cross-validation to identify the optimal features.

Finally, a set of 10 features included in the model was selected as the best feature combination. The risk score was computed based on the product of each feature’s expression value and its corresponding coefficient (b), determined by the multivariate Cox risk regression model. Patients were categorized into either a high-risk or a low-risk group based on the median of the IRGPI score. The Myeloma risk-score is the sum of the exponential of gene1 times b1, plus the exponential of gene2 times b2, up to the exponential of genen times bn.

Using the results of the Cox regression analysis involving multiple factors, we developed a prognostic model for overall survival. The discriminatory ability of this prognostic model was evaluated by constructing Kaplan–Meier survival curves. Additionally, we calculated the area under the ROC curve (AUC) to further assess the performance of the prognostic model for 3-year survival.

Statistical analysis and processing

Differences in expression levels between the two MAIC subtypes were assessed using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. To investigate the correlation between MAIC subtypes and clinical outcomes, we generated survival curves employing the Kaplan–Meier method and determined statistical significance using the log-rank test (Mantel-Cox). The creation of survival curves was facilitated by the R package "survminer." To evaluate the prognostic value of the 10 genes, we utilized the survival package ROC to construct ROC curves and calculate the AUC33. All statistical analyses were conducted in R (https://www.r-project.org/) to assess the expression correlations among genes within the prognostic model. P values below 0.05 were regarded as indicating statistical significance.

Results

Collection of basic information on the training cohort

A total of 859 patients were included in the study, constituting the training cohort from the MMRF-CoMMpass database. All clinical patient information can be found in Table 1. Patients with MM were categorized based on clinical ISS grading and were separated into three stages4. In terms of gender distribution, male patients outnumbered female patients, although the differences between the sexes were not found to be statistically significant across the three disease stages (as determined by the chi-square test, not significant). With regard to racial composition, white individuals were the most represented in the training cohort, exhibiting significant disparities compared to other racial groups (chi-square test, P < 0.001). As previously mentioned, within the subsequent immune-related subgroup, the MAIC groups, significant differences were observed between patients in the MM II and III stages within the MAIC1 group (Fisher’s exact test, P < 0.001). Furthermore, a significant distinction was noted among male patients within the MAIC groups across MM stages II and III (Fisher’s exact test, P < 0.001, Table 1).

MM-associated immune-related clustering performed on the training dataset

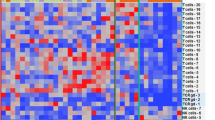

Upon performing consensus clustering to identify two primary subgroups with noticeable heterogeneity in immune cell infiltration within the training cohort, we designated them as MAIC1 (N = 482) and MAIC2 (N = 377), respectively (Fig. 1A. Subsequently, we consolidated all patient information from these two clusters and assessed the Kaplan–Meier survival curve between them. The overall survival curve (OS) revealed that the MAIC1 subgroup exhibited a poorer clinical prognosis compared to the MAIC2 group (P = 0.0066, Fig. 1B). We then summarized the detailed characteristics of tumor stromal status and clinical data for all 859 patients (Fig. 1C). In the MAIC1 subgroup, an elevation in various cell types was predominantly concentrated. These included Th2 cells, Th1 cells, preadipocytes, common lymphoid progenitor (CLP), myocytes, osteoblasts, smooth muscle cells, CD4 + cells, myeloid erythroid progenitor (MEP) cells, fibroblasts, and pericytes, among others, when compared to the MAIC2 group. The increased presence of these cell populations was significantly associated with a more adverse trend in the MAIC1 subgroup. Notably, the common lymphoid progenitor cell plays a pivotal role as the origin of specific B-cell malignancies, suggesting that any abnormal mutations within it impair cellular functionality, leading to gradual deterioration and eventual tumor formation34. Preadipocytes in the bone marrow have been confirmed to differentiate into mature adipocytes and are increasingly recognized for their involvement in promoting myeloma malignancy35,36. Additionally, the aberrant regulation of osteoblasts in the MAIC1 group suggests an imbalance in the expression of inflammatory and other cellular factors within the bone marrow microenvironment, resulting in osteoblast suppression37,38. Conversely, the MAIC2 group, characterized as the immune-active type, exhibited a more diverse population of immune cells compared to the first group. Notably, various immune cells such as B cells, naive B cells, mesenchymal stem cells (MSC), naive CD8 + T cells, memory B cells, GMP, DC, cDC, monocytes, macrophages M1, and macrophages M2 displayed significantly higher relative expression levels in the MAIC2 group. This diversity of cell types indicates an inflammation-like status within the MAIC2 group, suggesting a more favorable bone marrow environment for MAIC2 patients compared to the MAIC1 group.

Identification of two immune subtypes (MAIC1/MAIC2) in multiple myeloma training cohort. (A) Consensus clustering matrix for K = 2 subgroups. (B) Kaplan–Meier survival curves showing significantly worse outcomes in MAIC1 (brown, N = 482) versus MAIC2 (blue, N = 377) (P = 0.0066, log-rank test). (C) Integrated heatmap of clinical features (MM stage, gender, race) and immune cell composition. Black boxes highlight cell types with significant inter-subtype differences (***P < 0.001, log-rank test).

MAIC groups represent different immune heterogeneity

To gain a more precise understanding of immune cell infiltration in this MM study, we employed the CIBERSORT algorithm. Our analysis encompassed the overall performance of LM22 cell components from 859 patients (Fig. 2A).

Immune cell infiltration patterns in MM training cohort. (A) Stacked bar plot of 22 immune cell proportions across 859 patients (CIBERSORT). (B) Correlation matrix of immune cells (ssGSEA). Red/blue gradients indicate positive/negative correlations (range: − 1 to 1). (C) Differential immune cell abundance between MAIC1 and MAIC2 (Wilcoxon test). Significance levels: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

As mentioned earlier, correlations among immune cell infiltration results in myeloma patients were computed. Notably, a negative correlation was observed between plasma cells and memory B lymphocytes in this Pearson correlation matrix (Fig. 2B), with both displaying a positive correlation with naive B lymphocytes. Additionally, a clear positive relationship was evident between M1 macrophages, regulatory T cells, and immature B cells with resting dendritic cells. Monocytes, on the other hand, exhibited a positive correlation with several cell types, including immature B lymphocytes, memory B lymphocytes, regulatory CD4 + T cells, immature CD4 + T lymphocytes, follicular helper T cells, and gamma delta T cells (Fig. 2B). Moreover, the differences in the distribution of immunological data between the two MAIC groups were compared using the Wilcoxon test (Fig. 2C). The analysis revealed significant variations in the composition of several immune cells (asterisks indicate statistical differences). Specifically, compared to the MAIC2 subgroup, a higher proportion of memory B lymphocytes (P = 2.34e − 06), eosinophils (P = 1.81e − 08), activated memory T cells (P = 3.03e − 03), and resting memory T cells (P = 8.99e − 06) were observed in the MAIC1 group. Conversely, most other immune cells demonstrated a higher distribution in the MAIC2 group, including naive B cells, activated dendritic cells, resting dendritic cells, M2 macrophages, activated mast cells, resting mast cells, monocytes, neutrophils, activated NK cells, and CD8 + T cells, among others (Fig. 2C).

Subsequently, the TPM (Transcripts Per Kilobase of exon model per Million mapped reads) data from the training set was input into the R package ESTIMATE to compute the ESTIMATE score, Stromal score, and Immune score for MM patients. Regardless of the score type, whether it was the ESTIMATE score, Immune Score, or Stromal Score, it was observed that these scores were significantly lower in MAIC1 compared to the MAIC2 group (Fig. 3A).

Furthermore, ssGSEA analysis for the three distinct score types in the two groups was performed. This method allows for the integration of gene expression levels from individual samples to conduct enrichment analysis and score each sample based on immune cell or immune pathway-related characteristics (Fig. 3B). In summary, Fig. 3B presents the distribution of 28 immune-infiltrating cell types across the two MAIC subsets. Notably, in myeloma patients belonging to the immunosuppressive MAIC1 group, there is a marked reduction in both the number and distribution of these cell types. Conversely, the analysis results for these 28 immune-infiltrating cell types clearly indicate significantly higher expression levels in MAIC2 patients.

DE-IRGs identified between MAIC subgroups

It is well-established that multiple myeloma cells can induce an immunosuppressive state in the TME within other immune cells. Therefore, it is pertinent to select differentially expressed immune-related genes (DE-IRGs) from both immune states to elucidate the potential biological properties of DE-IRGs within these two MAIC subsets. We identified a total of 1947 DE-IRGs in the two subgroups, with 650 genes being upregulated in MAIC1 and 1297 genes downregulated in MAIC2 (Fig. 4A). Notably, among the top five most prominently upregulated genes in the MAIC1 group were PTN, CDH2, ADAM22, GABRB2, and NTRK, among others. PTN, a secreted growth factor, plays a functional role in various biological processes within tumors, including tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis39.

Differentially expressed immune-related genes (DE-IRGs). (A) Volcano plot demonstrating the differentially expressed immune-related genes (DE-IRGs) between the two MAIC subgroups, identifying genes with significant upregulation (log2 fold change > 1 and p-value < 0.05). The plot represents the magnitude and significance of gene expression changes, with the size of the dots indicating the magnitude of differential expression. (B) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of MAIC1-upregulated genes, identifying significant biological pathways associated with the tumor microenvironment and immune response. The analysis highlights functional categories enriched for genes regulated in MAIC1 subgroup. (C) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of MAIC2-upregulated genes, with bubble size indicating the number of genes contributing to each pathway. (D) Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis for MAIC1-upregulated genes, focusing on biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components. (E) Detailed GO enrichment results for MAIC1-upregulated genes, showing specific pathways and their relevance to multiple myeloma progression. (F) Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) results for MAIC2 group, identifying predicted biological pathways enriched in immune-active state. (G) GSEA results for MAIC1 group, identifying biological pathways enriched in immune-dysfunctional state.

CDH2 (N-cadherin) is known to be a key player in bone marrow malignancies, mediating the protective effect of cancer cells against chemotherapy and contributing to treatment resistance in leukemia40. ADAM22 has been implicated in targeting breast cancer, and clinical trials using the peptide analog LGI1MIM to target ADAM22 for the treatment of metastatic brain disease in breast cancer patients have been conducted41. GABRB2, a critical tumorigenic factor, serves as a novel oncogene in the context of papillary thyroid carcinoma42; NTRK is involved in neurotrophic signaling and holds significance in neuronal development and function, among other roles. Conversely, in the MAIC2 group, the most prominently upregulated genes included S100A9, CD83, IL-1β, LAPTM5, and the CXCLX family (except CXCL17), among others (see Fig. 4A and Table 2).

These proteins form a common heterodimer structure known as S100A8/A9 and have been widely reported to participate in multiple signaling pathways within tumor cells43. CD83, a marker for mature dendritic cells, holds significant importance in regulating immune responses and resolving inflammation. Particularly, CD83’s presence on the cell membrane plays a crucial role in the maturation of CD4 + T cells and contributes to the suppression of autoimmunity by promoting regulatory mechanisms that dampen excessive immune responses44. IL-1β, one of the 11 members of the IL-1 family, is now considered a therapeutic target for various autoinflammatory diseases, including SMM45. LAPTM5 encodes a transmembrane receptor associated with lysosomes. Upon BCR stimulation, LAPTM5 mRNA expression increases, leading to apoptosis of immature B cells through two distinct pathways It induces the internalization of BCR, consequently reducing the phosphorylation of SYK and ERK46. Furthermore, the CXCLX family, which comprises chemokines, including the CXC subfamily, plays a pivotal role in attracting and mobilizing various types of immune cells, regulating tumor behavior, promoting angiogenesis, and closely associating with the development of tumors and inflammatory diseases47.

Subsequently, we conducted GO and KEGG enrichment analysis of the upregulated metabolism-related genes in each MAIC subgroup. MAIC2 exhibited enrichment in biological processes such as immunoglobulin-mediated immune response, humoral immune response, and leukocyte migration (Fig. 4B and Table S1 in Supplementary Materials). In contrast, MAIC1 displayed enrichment in calcium-dependent cell adhesion through plasma membrane cell adhesion molecules, regulation of membrane potential, regulation of postsynaptic membrane potential, and synaptic tissue (Fig. 4D and Table S in Supplementary Materials). It was observed that gene sets in the MAIC2 group were significantly enriched in the complement and coagulation cascade, NF-κB signaling pathway, TNF signaling pathway, Toll-like receptor signaling pathway, and other related signaling pathways (Fig. 4D). Conversely, gene sets in the MAIC1 group were significantly enriched in signaling pathways related to neuroactive ligand-receptor interactions (Fig. 4E).

MAIC-derived DE -IRGs-investigation of prognostic potential

To assess the prognostic potential of the differentially expressed genes (N = 1947) between MAIC subtypes, univariate Cox analysis was performed. This analysis identified 633 differential genes that demonstrated statistical significance for prognosis (see Table S3 in Supplementary Materials). These prognostically relevant differential genes were functionally enriched in various biological processes (BP), molecular functions (MF), and cellular components (CC) (Fig. 5A), indicating their diverse roles. Significant differences were observed in processes related to T-cell activation, leukocyte formation, and cell adhesion, among others. In the pursuit of independent prognostic factors, LASSO analysis was employed to identify markers that could independently predict multiple myeloma outcomes. Ten independent prognostic factors were identified, namely UBE2T, E2F2, EXO1, SH2D2A, DRP2, WNT9A, SHROOM3, TMC8, CDCA7, and GPR132 (Fig. 5B and Table S4 in Supplementary Materials). The co-expression of these 10 independent prognostic factors was further examined (Fig. 5D), along with their expression patterns in the two immune subtypes. The impact of these 10 genes’ expression on overall survival was assessed (Fig. 5).

A prognostic index was then constructed for all cancer samples using the following calculation formula:

The Kaplan–Meier survival curve demonstrated that patients classified as low-risk in the context of multiple myeloma had significantly longer survival compared to patients classified as high-risk (log-rank test, P < 0.001). The prognostic model’s predictive performance was evaluated using the ROC curve, with an AUC of 0.714 over 5 years, indicating superior predictive power. Additionally, Fig. 5E displays ROC curves for the 1-year, 3-year, 5-year, and 7-year periods. In the validation cohort (GEO data), the prediction model built using these 10 genes showcased significant differences in survival between the low-risk and high-risk groups (log-rank test, P < 0.001). The model’s performance was further assessed using ROC curves, which are shown for 1-year, 5-year, and 7-year periods in Fig. 5F. To gain a deeper understanding of the diagnostic potential of the 10 genes, we performed additional MMRF survival analyzes for each gene. The results of these analyzes can be seen in Fig. 6, where we present the results of the survival analysis specifically for the 10 genes that are part of the diagnostic panel. These results further contribute to our assessment of the diagnostic capacity of these genes and provide valuable insight into their association with patient survival in the context of multiple myeloma.

Discussion

Project background and research necessity

In clinical oncology, significant strides have been made in the application of NGS technology for the comprehensive analysis of tumor genetics. This technology has afforded researchers a deeper understanding of genetic abnormalities, including the identification of oncogenes that drive tumor growth. By scrutinizing tumor cells at the molecular level, scientists can explore potential therapeutic avenues48. In the realm of hematology and oncology, blood samples present a wide array of cell types and quantities49. NGS has empowered us to dissect transcriptomic information, cellular functionalities, and the TME, among other aspects. This comprehensive approach aids in unraveling the intricacies of tumor progression and dissemination, facilitating personalized clinical interventions and precise targeted therapies. However, in the context of multiple myeloma, the immune cell status within the TME and its bidirectional relationship with tumor development remain enigmatic. It is widely recognized that the “niche” serves as the fundamental unit for immune cells within the myeloma related TME21,49. As the neoplastic stage advances, the activity of myeloma cells frequently intertwines with that of immune cells within these "niches," potentially influencing tumor progression by regulating myeloma cell proliferation and viability. This study draws upon the MMRF-CoMMpass database for immune-related investigations, driven by several compelling reasons: Firstly, this database boasts the largest available sample size (at least the open resources available to us ), excluding single-cell sequencing data22; Secondly, prior scholars have not explored this database through the lens of immunologically relevant genetic markers, leaving a knowledge gap. Thirdly, we posited that myeloma cells situated in the "bone marrow niche" act as the driving force that induces a state of immune dysfunction or immunosuppression by manipulating the surrounding immune cells. This manipulation ultimately fosters malignant myeloma cell growth, granting them dominance and the ability to evade immune surveillance. In such scenarios, patients inevitably face dismal prognoses. Finally, our focus on CD138 + myeloma cells provided high-purity transcriptional profiles of malignant plasma cells but inherently limited our ability to resolve stromal-immune crosstalk. For example, CXCL12, a key chemokine secreted by stromal cells—was underrepresented in our analysis, potentially underestimating its role in MAIC1 immune dysfunction. However, this approach aligns with our hypothesis that myeloma-intrinsic genes drive microenvironmental reprogramming, as evidenced by the prognostic power of tumor cell-specific markers like UBE2T and E2F2. To reconcile this, future studies will integrate whole bone marrow RNA-seq or spatial transcriptomic to disentangle tumor-autonomous versus stromal-driven immune suppression. Built upon this hypothesis, we harnessed various immune algorithms to dissect the RNA sequencing data of CD138 + myeloma cells. This RNA expression profile allowed us to delineate the functionality and distribution of immune cells within the myeloma TME. In essence, it elucidates the internal forces at play within cancer cells that result in an altered gene expression profile, culminating in immune cell suppression. Furthermore, at the outset of our study, we contemplated employing two distinct immune cell sorting algorithms (xCELL and CIBERSORT) for analysis. Remarkably, the results obtained from both methods exhibited a relatively high degree of consistency (Figs. 1C and 2), underscoring the reliability of our analytical approaches.

Research results and theoretical extension

Intracellular cell signaling within immune cells exerts a significant influence on the survival and immune evasion mechanisms employed by multiple myeloma cells. This encompasses the distribution and functionality of T cells within both the immune system and peripheral blood 49. A multitude of studies have elucidated that in the peripheral blood of individuals with multiple myeloma, there is a reduction in the proportion of CD4 + and CD8 + components, an aberrant Th1/Th2 ratio, compromised T cell functionality, and a diminished count of NK T cells50. In the activated bone marrow microenvironment where multiple myeloma cells thrive, T cells often exhibit signs of immunosuppression, exhaustion, and cellular senescence21,51. In the scope of our research, we have observed a notable increase in the abundance of Th2 cells within the subgroup of individuals characterized by immune suppression when compared to another group.

Th2 cells are renowned for their pivotal role in the immune response, particularly in combatting parasitic infections and mitigating allergic reactions. They accomplish this by secreting specific proteins known as cytokines, including IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, which wield significant influence over the immune response, aiding in the effective clearance of parasites and counteracting allergic reactions52. However, in the context of multiple myeloma, Th2 cells primarily assume an immunosuppressive function, especially within the bone marrow microenvironment of multiple myeloma. Cytokines secreted by Th2 cells, such as IL-10 (a key anti-inflammatory molecule), possess the capability to inhibit the activity of Th1 cells and reduce the antigen processing and presentation functions exhibited by various cells53. This shift in the myeloma TME may afford tumor cells the means to elude immune surveillance and foster the progression of multiple myeloma. Some studies have suggested that a high proportion of Th2 cells in multiple myeloma may signify a poor response to treatment. Conversely, other research, such as that conducted by Qing Yi et al., has reported that Th1 and CTL can suppress the growth of multiple myeloma cells54. Additionally, Th2 cells promote the proliferation of multiple myeloma cells by augmenting the secretion of antibody heavy chain-specific protein (Idiotype protein, Id), alongside other cytokines54. Th2 cells, along with the cytokines they secrete, might also exert an impact on bone metabolism, primarily by enhancing osteoclast activity, thereby exacerbating bone destruction in multiple myeloma34. The extent of bone damage in multiple myeloma steadily worsens, contributing to a myriad of disease burdens35. Consequently, it can be inferred that manipulating the Th1/Th2 balance in multiple myeloma holds promise as a therapeutic strategy55.

Secondly, in accordance with our data, an elevated expression of preadipocytes was discerned within the cellular milieu of the immunosuppressed subset, denoted as the MAIC1 group, among MM patients. This observation suggests a reciprocal interaction transpiring between MM-derived BMAd and the multiple myeloma cells within individuals belonging to the immunosuppressed subset. Furthermore, multiple myeloma sets in motion a “vicious cycle” by reshaping the phenotype of preadipocytes: the augmented presence of preadipocytes not only fosters the proliferation and homing of multiple myeloma cells, culminating in their accumulation within the patient’s bone marrow, but also results in the domination of multiple myeloma within the patient’s bone marrow. Preadipocytes represent the precursor cells of adipose tissue and are a constituent of the bone marrow. The association between adipocytes and MM has long piqued the interest of medical experts.

This is because the onset of MM exhibits a correlation with age, and the proportion of BMAd is rarely low in human infants, but it can ascend to as much as 70% in the elderly, indirectly underscoring the connection between BM fat cells and MM56. In 2016, Trotter et al. unearthed that the number of BMAd and preadipocytes experiences an upsurge in individuals afflicted with multiple myeloma, and these cells also exhibit a pro-cancer inclination36. More recently, researchers have unveiled that after an in vitro co-culture of preadipocytes and multiple myeloma cells, myeloma cells incite a specific phenotypic transformation in preadipocytes through the secretion of MM-supportive cytokines, ultimately leading to the senescence of preadipocytes. This suggests that bone marrow-derived adipose tissue cells from multiple myeloma serve as one of the sources of cellular signaling that trigger the homing behavior of myeloma cells41.

Extrapolating from the data depicted in Fig. 2C, the cellular composition of the MAIC2 group surpasses that of the MAIC1 group to a significant extent. This phenomenon could be attributed to the immunosuppressed state of the MAIC1 group, suggesting that the state of immunosuppression has matured, and the microenvironment has succumbed to the dominance of myeloma cells that proliferate malignantly. For instance, M2 macrophages within the multiple myeloma tumor microenvironment undergo polarization induced by MM cells, subsequently promoting various tumor activities, such as MM cell homing, myeloma cell proliferation, angiogenesis, among others57. However, the results depicted in Fig. 2C do not unequivocally substantiate this observation. We propose that a bidirectional regulatory mechanism exists between the cells within the myeloma and its immune microenvironment. While the tumor cells are suppressed by normal immune cells, thereby retarding their tumorigenicity, the myeloma cells, in turn, cause the BM microenvironment to descend into an immunosuppressive state58.

Notably, the results gleaned from our GO and KEGG enrichment analysis of DE-IRGs reveal that the MAIC2 cluster primarily engages in immune-related regulatory pathways and signaling activities pertinent to tumor cells within the myeloma microenvironment. Specifically, it is implicated in immunoglobulin-mediated immune response, humoral immune response, and leukocyte migration (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, it plays a role in cancer-associated signaling pathways such as osteoclast differentiation, NF-κB signaling, and PI3K-Akt signaling (Fig. 4C). Conversely, the discerned biological activities associated with the MAIC1 subset exhibit a relatively weak correlation with tumor cell activities, as the results predominantly revolve around the neuronal signaling pathway (Fig. 4).

While our computational analyses robustly associate Th2 cell enrichment and CXCL dysregulation with immune dysfunction in MM, we emphasize that these findings represent correlative insights rather than mechanistic proof. Bulk RNA-seq-based deconvolution (e.g., xCELL/CIBERSORT) infers cell-type proportions from transcriptional signatures, which may not fully capture post-translational modifications or spatial interactions critical to Th2-mediated immunosuppression. For instance, elevated Th2 scores could reflect either true cellular abundance or altered cytokine secretion profiles. Similarly, CXCL family expression changes may arise from tumor cell-autonomous signaling or stromal crosstalk, necessitating spatial transcriptomics or multiplex immunohistochemistry for validation. Notably, our observation of CXCL12 downregulation in the MAIC1 subgroup contrasts with prior reports linking CXCL12 upregulation and also CXCL12/CXCR4 axis plays a key role in the homing of normal and MM cells at BM level59. This discrepancy may stem from differences in sample selection (e.g., CD138 + only vs. whole bone marrow profiling) or the temporal dynamics of CXCL12 expression during disease progression. Future studies integrating longitudinal samples and stromal compartment analysis are needed to resolve this paradox60.

The expression profile of CXCLx is notably higher in the MAIC2 group in comparison to the MAIC1 group (see Table 2), with the exception of a slight upregulation of CXCL17 in the MAIC1 group (see Table 2, P = 0.0019). As widely acknowledged, the CXCLX belongs to the CXC subfamily of chemokines, primarily involved in tumor initiation, development, and metastasis54. These chemokines are adept at attracting and activating immune cells, consequently influencing the infiltration of inflammatory cells, and thereby altering the composition and function of the TME61,62. Furthermore, the CXCL family can directly incite the migration of immune cells, such as T cells and macrophages, to the tumor site by binding to specific receptors63.

Moreover, the expression of the CXCL family is entwined with tumor drug resistance and may serve as a pivotal prognostic indicator for tumors64,65. Ordinarily, when normal human cells maintain the expression of CXCLx-related proteins, they can effectively entice and mobilize immune cells to launch attacks on and eliminate nascent tumor cells, constituting one of the body’s defense mechanisms. However, when the expression of CXCLX-related proteins diminishes, these immune cells may no longer be efficiently drawn to the tumor cell locale. In such an instance, the tumor cells might “elude” the immune system’s assault, an occurrence referred to as "immune escape." In summary, the dwindling expression of the majority of CXCLX family molecules in tumor cells may heighten the difficulty for the immune system to locate and eradicate these tumor cells, consequently enhancing the tumor’s ability to evade the immune system. In the context of myeloma, the aberrant regulation of the CXCR4/CXCL12 axis has been linked to multiple important cellular signaling pathways, playing a role in osteoclast genesis and tumor proliferation in multiple myeloma65. As for CXCL17, it serves as a chemokine that attracts dendritic cells and macrophages, although it can also be expressed in other bodily regions during episodes of inflammation. CXCL17 exerts an influence on T cell homeostasis and function, thereby harboring potential implications for the treatment of autoimmune disorders or cancer66,67.

Based on our findings, it is conceivable that these two MAIC subpopulations may represent two distinct phases of multiple myeloma, characterized by their immune cell characteristics. Specifically, the immune-suppressive MAIC1 subpopulation exhibits indications of immune dysregulation and immune cell exhaustion. During this phase, myeloma cells assume a dominant role in the multiple myeloma bone marrow environment, leading to widespread suppression of immune cells, which has a detrimental impact on patient survival and prognosis. In contrast, the MAIC2 subpopulation represents a dynamic phase characterized by reciprocal interactions between myeloma cells and immune cells, with immune cells persisting in their role of maintaining immune defenses. It is important to note that immunosuppression typically arises from the interplay of three key factors. Firstly, it involves the dysfunction and/or depletion of effector lymphocytes. Secondly, it encompasses the inhibition of metabolites and cytokines that hinder anti-tumor immunity. Lastly, it entails the generation and mobilization of immunosuppressive cells15,21,58. Thus, we can confidently affirm that the MAIC1 group exhibits a state of immune dysfunction. Based on these findings, the next step would be to use the immune dysfunction status of the MAIC1 subgroup as a clinical entry point, proposing the following strategies to improve treatment outcomes. Patient Stratification: The MAIC1 subtype (immune-dysfunctional) in this study and high-risk IRGPI scores could identify patients may be unlikely to respond to PD-1/IMiD combinations (e.g., pembrolizumab + lenalidomide). These patients may benefit from alternative strategies, such as CAR-T therapy targeting BCMA or GPRC5D68. Immunotherapy Trial Design: We suggest stratifying patients in upcoming anti-CD38/anti-SLAMF7 trials (e.g., isatuximab + elotuzumab) by MAIC subtype to evaluate whether immune-active MAIC2 patients exhibit enhanced NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity69.Dynamic Monitoring: The IRGPI score could serve as a liquid biopsy biomarker to track immune microenvironment remodeling during daratumumab therapy, akin to ctDNA monitoring in solid tumors70.

Since we consider the MAIC1 subpopulation to represent immunocompromised patients, it is reasonable to use genetic markers obtained from immune-related cell selection to predict the prognosis of multiple myeloma patients. Among the 10 DE-IRGs, namely UBE2T, E2F2, EXO1, SH2D2A, DRP2, WNT9A, SHROOM3, TMC8, CDCA7, and GPR132, many have been well-documented in research and are closely linked to various tumors, including multiple myeloma. For example, the UBE2T gene is responsible for producing a crucial enzyme for DNA repair. Mutations in UBE2T have been detected in several cancer types, including multiple myeloma, leading to higher expression levels in MM patients, particularly in those with advanced stages of the disease71. Increased UBE2T expression is linked to disease advancement, the growth of myeloma cells, and worsening of symptoms in multiple myeloma patients72. Experimental evidence suggests that inhibiting UBE2T can lead to the death of multiple myeloma cells. Interestingly, our results show that UBE2T gene expression is significantly upregulated in the high-risk group compared to the low-risk group (Fig. 6, P < 2.2e-16). E2F2 encodes a crucial transcription factor that plays a central role in regulating cell growth and division. Recent research has highlighted the close connection between E2F2 and tumor progression, underscoring its significance as a DE-IRG in stomach adenocarcinoma73. Additionally, one study has revealed that E2F2 promotes the development of MM by inhibiting PECAM1-dependent cell adhesion and accelerating myeloma cell proliferation. Consequently, E2F2 has the potential to function as an independent prognostic marker and therapeutic target for MM74. Based on the data obtained, there is an increasing trend in the expression of the E2F2 gene in the MACI1 subset (in comparison to the MAIC2 group, Fig. 6, P < 0.0001). As we know, the EXO1 gene plays a role in repairing DNA damage75. Researchers have reported that polymorphic variations in the EXO1 gene can serve as biomarkers for assessing chemotherapy drugs in patients with malignant lymphoma76. In the low-risk group, a decrease in the expression of the EXO1 gene suggests a potential link between EXO1 gene expression and the prognosis of multiple myeloma (compared to the high-risk group, Fig. 6, P < 2.2e − 16). Similarly, the SH2D2A gene encodes a T-cell-specific adapter protein responsible for T-cell activation and cellular signal transduction. In 2012, researchers discovered that SH2D2A plays a crucial role in T cell-mediated cancer immune surveillance77. Based on our data, we also clearly observed a significant increase in the expression of the SH2D2A gene in immunosuppressed patients (compared to the low-risk group, Fig. 6, P < 2.2e − 16). We also mentioned the CDCA7 gene, which encodes a protein involved in DNA replication processes during cellular division and is implicated in various malignancies, including Burkitt lymphoma. Overexpression of CDCA7 increases the risk of B-cell malignancies and other lymphomas, while a deficiency in CDCA7 effectively reduces tumor cell proliferation78. However, based on our research findings, there was a decrease in the expression levels of CDCA7 in the high-risk group, which contradicts the conclusions drawn from existing literature (compared to the low-risk group, Fig. 6, P < 2.2e − 16).

On the other side, this study centers on the construction of a transcriptomic predictive model targeting immune microenvironment features in MM, with the goal of developing innovative predictive tools through an innovative immune stratification strategy. These tools aim to provide theoretical and practical guidance for individualized diagnosis and treatment of MM. Recent in genomic rapid advances, the extensive application of transcriptomic data mining in public MM datasets, have significantly enhanced the understanding of the MM cancer biology79. Specifically, the breakthrough application of single-cell transcriptomic sequencing has led to more powerful in the accuracy and generalizability of MM predictive systems80,81. In the context of clinical prognostic stratification systems, numerous molecular markers and statistical predictive models have been established by the academic community, with the R-ISS system being the most representative4. Notably, with the advancement of precision medicine research, integrative analyses of multi-omics data have led to the iterative development of multi-dimensional prognostic evaluation systems, such as the R-ISS series models82,83,84. These novel evaluation systems have significantly enhanced the precision of prognostic assessment, furnishing scientific evidence for the formulation of individualized treatment regimens81,85,86,87.It is noteworthy that predictive tools based on genetic mutation characteristics are rapidly evolving, which not only enhance the granularity of clinical decision-making processes but also provide new perspectives for the formulation of targeted therapy strategies81,88. By systematically integrating multi-omics data, researchers can offer more precise therapeutic recommendations for patients84, which facilitates real-time monitoring of disease progression and provides reliable for the dynamic optimization of MM clinical treatment plans, ultimately advancing the practice of precision medicine.

Study limitations

Honestly, this study has several limitations: Firstly, as we know, our study is inherently limited by the absence of detailed bone marrow transplantation (BMT) status in the MMRF-CoMMpass and GEO datasets, which might not be openly detailed in public online resources. This omission is significant because BMT, a common treatment modality for MM, can profoundly influence the TME and immune reconstitution. Patients who undergo BMT may experience substantial changes in immune cell composition and functionality, which could alter the classification of immune subtypes and the performance of predictive models58,88,89,90. Moreover, it is essential to recognize that, regardless of whether MM patients receive BMT or not, the immunosuppressive state of the BM in advanced stages significantly impacts therapeutic outcomes, survival quality, even in economic burden91. These factors are closely aligned with the overarching goal of our study, which seeks to elucidate immune phenotypes and predict prognosis. Thus, the absence of BMT status information in our datasets could introduce confounding effects on immune subtype classification and prognostic model performance, potentially compromising the generalizability and accuracy of our findings. Recognized these limitations, we are planning future studies to incorporate BMT-related data through multi-center collaborations to addressing this gap, we hope to provide a more robust framework for risk-stratified immunotherapy in MM patients.

Secondly, we aimed to analyze stromal mutations, often referred to as mutation burden, in relation to the immune state of myeloma in this research. Unfortunately, after conducting statistical analyses, we did not observe a significant difference in stromal mutations between the two MAIC subsets (Figure S2). The findings can be summarized as follows: missense mutations were the most frequent type in MM, with C > T being the primary base mutation in both groups. Secondly, the occurrence ratio of IGHV2-70 gene mutations was highest among the patients (Mutation frequency: MAIC1 vs. MAIC2 is 65% to 59%, chi-square test, P > 0.05). Thirdly, there were two notable changes in the mutation ratio of key genes associated with MM progression, namely DIS3 (Mutation frequency MAIC1 vs. MAIC2 is 9–13%, chi-square test, P > 0.05), and the FAM46C gene (MAIC1 vs. MAIC2 is 11–9%, chi-square test, P > 0.05). It is worth mentioning that DIS3 genetic mutations are prevalent in approximately 10% of myeloma patients and are often associated with monosomy 13 and del (13q). Researchers have considered DIS3 as an independent predictive factor by analyzing somatic mutations in the MMRF-CoMMpass data, suggesting that DIS3 mutations may alter biological processes in the transcriptome of myeloma cells, as well as RNA metabolism-related cellular signal pathways92. The FAM46C gene, a recently discovered protein inhibitor associated with MM, encodes proteins responsible for regulating protein trafficking and secretion. In myeloma patients, mutations in the FAM46C gene may lead to increased protein transfer and ER stress within tumor cells93. As we are aware, the mutation burden in tumor cells is closely linked to changes in the immune status of the TME. A high mutation burden results in the appearance of new antigens on the surface of tumor cells, enhancing the immune system’s ability to recognize and attack tumors, thereby activating the immune response. These new antigens on tumor cells can enhance the capability of immune cells to target tumors and influence the sensitivity of immunotherapy, ultimately enhancing treatment effectiveness. However, alterations in the immune system may inhibit its response, reducing its effectiveness in combating tumors, which can lead to increased tumor cell proliferation and a decrease in the mutant load. This, in turn, may result in the generation of additional new mutations. The mutational burden of tumor cells and their altered immune status are interconnected. An increased mutation burden leads to the presentation of more neoantigens on the surfaces of tumor cells, enhancing the immune system’s ability to recognize and combat tumors, thereby triggering immune responses94. Conversely, the presence of these neoantigens on tumor cells can enhance the efficacy of immune cells against tumors and modify the sensitivity of immunotherapy, ultimately improving clinical treatment outcomes95. However, alterations in immune status may hinder the immune system’s response, reducing its ability to eliminate tumors and allowing for increased tumor cell proliferation. This process may lead to a decreased mutational burden, potentially resulting in the generation of additional new mutations96.

Thirdly, the cellular pathways examined in the MAIC1 subgroup primarily revolve around four main aspects: (a) calcium-dependent cell adhesion of plasma membrane cell adhesion molecules, (b) regulation of membrane potential, (c) regulation of postsynaptic membrane potential, and (d) enrichment of synaptic organization (see Fig. 4D). Currently, there is no direct evidence linking these specific cellular pathways to the biological behaviors of multiple myeloma cells. An exception to this is the case of thalidomide, a drug used in multiple myeloma treatment. It has been discovered that thalidomide-induced hyperactivity of calcium-dependent potassium channels (Ca2+ active K+ channels) is responsible for the pathological mechanism leading to thalidomide-associated reversible memory loss in myeloma patients97. Several factors contribute to the limitations of GO/KEGG enrichment analysis. Firstly, the accuracy of gene enrichment analysis can be influenced by various factors. The quality of experimental data, including sample processing, sequencing technology, and data preprocessing, can all impact the results. Any issues at these stages may lead to results that diverge significantly from reality. Moreover, the precision of gene enrichment analysis tools like GO and KEGG relies on the quality and comprehensiveness of annotation databases. If these databases fail to comprehensively represent the characteristics of the specific tumor cells under investigation, the analysis outcomes may lack accuracy. Tumor heterogeneity is another factor that can affect the results since cells within the same tumor may exhibit diverse gene expression patterns. Our study has inherent limitations due to the constraints of bulk transcriptomic approaches. While bioinformatics tools efficiently prioritize candidate mechanisms, they cannot replace functional assays in confirming causality. For instance, although LASSO-selected genes such as SH2D2A and CDCA7 show prognostic significance, their roles in immune evasion require validation through CRISPR-based perturbation studies. Moreover, our understanding of biological processes, particularly in complex diseases like multiple myeloma, remains incomplete. Addressing these challenges necessitates advancements in experimental techniques, the adoption of more precise gene enrichment analysis tools, a deeper consideration of tumor heterogeneity, and continuous updates to our knowledge of disease biology.

Summary

In summary, our forthcoming research is centered on understanding the mechanisms and consequences of mutations in multiple myeloma cells concerning immune regulation. We will also investigate the connection between the mutation burden of tumor cells and immune checkpoints, as well as its potential impact on immunotherapy. Through this exploration, we aim to develop novel strategies and approaches for the treatment of multiple myeloma.

To recap, our study utilizes patient data from existing databases to analyze prognostic signatures related to the tumor microenvironment in multiple myeloma. Our goal is to advance personalized clinical treatment for multiple myeloma and identify potential beneficial biomarkers for targeted therapy. Recent research has shown that clinical phase III trials of anti-PD-1 blockade therapy have yielded unsatisfactory results in treating multiple myeloma20. This underscores the importance of a comprehensive evaluation of the disease status and progression in multiple myeloma, coupled with flow cytometry immunophenotyping. Our research findings are particularly well-suited for integration with flow cytometry techniques, enabling prognostic assessments of multiple myeloma patients.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study has provided valuable insights into the immunological subtypes of multiple myeloma (MM), a hematologic malignancy characterized by abnormal plasma cell proliferation influenced by both genetic factors and the tumor microenvironment. We have observed significant immune dysregulation in one subset, while another exhibits an inflammatory immune response, indicating the presence of diverse immune activities in MM. Most importantly, through the analysis of NGS data, we have identified ten crucial immune-associated genes (UBE2T, E2F2, EXO1, SH2D2A, DRP2, WNT9A, SHROOM3, TMC8, CDCA7, and GPR132) with potential prognostic significance in MM. The discovery of these genes underscores the molecular and immunological heterogeneity within MM and provides insights into novel clinical strategies. Furthermore, our research has led to the development of an immunodiagnostic model for MM, complementing existing techniques like flow cytometry and immunotyping.

Data availability

The related datasets during the current study are available in the TCGA GDC repository (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov) and GEO repository, (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), respectively

Abbreviations

- AUC:

-

The area under the ROC curve

- BMAd:

-

Bone marrow Adipocyte

- BCR:

-

B cell receptor

- BMAt:

-

Bone marrow adipose tissue

- BM:

-

Bone marrow

- CLP:

-

Common lymphoid progenitor

- cDC:

-

Conventional dendritic cell

- DC:

-

Dendritic cell

- DE-IRGs:

-

Differentially expressed immune-related genes

- EMM:

-

Extradentary multiple myeloma

- ERK:

-

Extracellular regulated protein kinases

- GEO:

-

Gene expression omnibus

- GMP:

-

Granulocyte–macrophage progenitor

- GSEA:

-

Gene set enrichment analysis

- IMiD:

-

Immunomodulatory drugs

- LGI1MIM:

-

A peptide mimetic of the ADAM22 ligand LGI1

- IRGPI:

-

Immune related gene prognostic index

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes

- K-M:

-

Kaplan–Meier

- MAICs:

-

Multiple myeloma-associated immune-related cluster

- MEP:

-

Myeloid-erythroid progenitor

- MGUS:

-

Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance

- MM:

-

Multiple myeloma

- MMRF-CoMMpass:

-

Multiple myeloma research foundation clinical outcomes in MM to personal assessment of genetic profile

- MSC:

-

Mesenchymal stem cell

- NGS:

-

Next generation sequencing

- PCL:

-

Plasmacytoma leukemia

- PD-1:

-

Programmed cell death-1

- PECAM1:

-

Platelet and endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1

- RNA-seq:

-

RNA sequencing

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- SMM:

-

Smoldering multiple myeloma

- SNV:

-

Single nucleotide variant

- SYK:

-

Spleen tyrosine kinase

- TCGA:

-

The cancer genome atlas

- TME:

-

Tumor microenvironment

- Th:

-

T helper cell

- TPM:

-

Transcripts per million

References

Brigle, K. & Rogers, B. Pathobiology and diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 33(3), 225–236 (2017).

Mateos, M. V. & Landgren, O. MGUS and smoldering multiple myeloma: Diagnosis and epidemiology. Cancer Treat. Res. 169, 3–12 (2016).

Waldenstrom, J. Studies on conditions associated with disturbed gamma globulin formation (gammopathies). Harvey Lect. 56, 211–231 (1960).

Greipp, P. R. et al. International staging system for multiple myeloma. J. Clin. Oncol. 23(15), 3412–3420 (2005).

Rollig, C., Knop, S. & Bornhauser, M. Multiple myeloma. Lancet 385(9983), 2197–2208 (2015).

Crowley, J. P. Smoldering multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 303(16), 941 (1980).

Kazandjian, D. Multiple myeloma epidemiology and survival: A unique malignancy. Semin. Oncol. 43(6), 676–681 (2016).

Lentzsch, S., Ehrlich, L. A. & Roodman, G. D. Pathophysiology of multiple myeloma bone disease. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am. 21(6), 1035–1049 (2007).

Cohen, A. D. Myeloma: Next generation immunotherapy. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Edu. Program 2019(1), 266–272 (2019).

Terpos, E., Ntanasis-Stathopoulos, I. & Dimopoulos, M. A. Myeloma bone disease: from biology findings to treatment approaches. Blood 133(14), 1534–1539 (2019).

Rajan, A. M. & Rajkumar, S. V. Interpretation of cytogenetic results in multiple myeloma for clinical practice. Blood Cancer J. 5, e365 (2015).

Raza, S., Safyan, R. A. & Lentzsch, S. Immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs) in multiple Myeloma. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 17(9), 846–857 (2017).

Finsinger, P. et al. Clinical features and prognostic factors in solitary plasmacytoma. Br. J. Haematol. 172(4), 554–560 (2016).

Pitt, J. M. et al. Targeting the tumor microenvironment: Removing obstruction to anticancer immune responses and immunotherapy. Ann. Oncol. 27(8), 1482–1492 (2016).

Dosani, T. et al. The cellular immune system in myelomagenesis: NK cells and T cells in the development of myeloma[corrected] and their uses in immunotherapies. Blood Cancer J. 5(4), e306 (2015).

Fidler, I. J. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: The “seed and soil” hypothesis revisited. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3(6), 453–458 (2003).

Das, R. et al. Microenvironment-dependent growth of preneoplastic and malignant plasma cells in humanized mice. Nat. Med. 22(11), 1351–1357 (2016).

Usmani, S. Z. et al. Pembrolizumab plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone for patients with treatment-naive multiple myeloma (KEYNOTE-185): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 6(9), e448–e458 (2019).

Manier, S. et al. Current state and next-generation CAR-T cells in multiple myeloma. Blood Rev. 54, 100929 (2022).

Zhang, Q. & Zhang, Z. Stepwise immune alterations in multiple myeloma progression. Nat. Cancer 1(5), 477–479 (2020).

Nakamura, K., Smyth, M. J. & Martinet, L. Cancer immunoediting and immune dysregulation in multiple myeloma. Blood 136(24), 2731–2740 (2020).

Shaw, M. L. The MMRF: Understanding and sharing the genomic landscape of multiple myeloma. Am. J. Manag. Care 27(9), SP392 (2021).

Settino, M. & Cannataro, M. MMRFBiolinks: An R-package for integrating and analyzing MMRF-CoMMpass data. Brief. Bioinform. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbab050 (2021).

Rao, L. et al. Targeting angiogenesis in multiple myeloma by the VEGF and HGF blocking DARPin(®) protein MP0250: A preclinical study. Oncotarget 9(17), 13366–13381 (2018).

Zhao, S., Ye, Z. & Stanton, R. Misuse of RPKM or TPM normalization when comparing across samples and sequencing protocols. RNA 26(8), 903–909 (2020).

Kuiper, R. et al. A gene expression signature for high-risk multiple myeloma. Leukemia 26(11), 2406–2413 (2012).

Wilkerson, M. D. & Hayes, D. N. ConsensusClusterPlus: A class discovery tool with confidence assessments and item tracking. Bioinformatics 26(12), 1572–1573 (2010).

Zhong, X. et al. Cellular components in tumor microenvironment of neuroblastoma and the prognostic value. PeerJ 7, e8017 (2019).

Newman, A. M. et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat. Methods 12(5), 453–457 (2015).

Yoshihara, K. et al. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nat. Commun. 4, 2612 (2013).

Bao, X. et al. A novel epigenetic signature for overall survival prediction in patients with breast cancer. J. Transl. Med. 17(1), 380 (2019).

Kanehisa, M. et al. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44(D1), D457–D462 (2016).

Heagerty, P. J., Lumley, T. & Pepe, M. S. Time-dependent ROC curves for censored survival data and a diagnostic marker. Biometrics 56(2), 337–344 (2000).

Green, M. R. & Alizadeh, A. A. Common progenitor cells in mature B-cell malignancies: Implications for therapy. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 21(4), 333–340 (2014).

McDonald, M. M. et al. Adipose, bone, and myeloma: Contributions from the microenvironment. Calcif. Tissue Int. 100(5), 433–448 (2017).

Trotter, T. N. et al. Adipocyte-lineage cells support growth and dissemination of multiple myeloma in bone. Am. J. Pathol. 186(11), 3054–3063 (2016).

Silvia Marino, G. & Roodman, D. Multiple myeloma and bone: the fatal interaction. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 8(8), a031286. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a031286 (2018).

Kristinsson, S. Y. et al. Bone disease in multiple myeloma and precursor disease: Novel diagnostic approaches and implications on clinical management. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 11(6), 593–603 (2011).

Liu, S. et al. Discovery of PTN as a serum-based biomarker of pro-metastatic prostate cancer. Br. J. Cancer 124(5), 896–900 (2021).

Parker, J. et al. Targeting N-cadherin (CDH2) and the malignant bone marrow microenvironment in acute leukaemia. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 25, e16 (2023).

Charmsaz, S. et al. ADAM22/LGI1 complex as a new actionable target for breast cancer brain metastasis. BMC Med. 18(1), 349 (2020).

Jin, Y. et al. GABRB2 plays an important role in the lymph node metastasis of papillary thyroid cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 492(3), 323–330 (2017).

Chen, Y. et al. S100A8 and S100A9 in cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 1878(3), 188891 (2023).

Grosche, L. et al. The CD83 molecule - An important immune checkpoint. Front. Immunol. 11, 721 (2020).

Lust, J. A. et al. Induction of a chronic disease state in patients with smoldering or indolent multiple myeloma by targeting interleukin 1beta-induced interleukin 6 production and the myeloma proliferative component. Mayo. Clin. Proc. 84(2), 114–122 (2009).

Wang, Y. et al. LAPTM5 mediates immature B cell apoptosis and B cell tolerance by regulating the WWP2-PTEN-AKT pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119(36), e2205629119 (2022).

Zhou, C. et al. The role of CXCL family members in different diseases. Cell Death Discov. 9(1), 212 (2023).

Mosele, F. et al. Recommendations for the use of next-generation sequencing (NGS) for patients with metastatic cancers: A report from the ESMO Precision Medicine Working Group. Ann. Oncol. 31(11), 1491–1505 (2020).

Choi, Y. S. Immuno-oncology for B-cell lymphomas. Blood Res. 56(S1), S70–S74 (2021).

Murakami, H., Ogawara, H. & Hiroshi, H. Th1/Th2 cells in patients with multiple myeloma. Hematology 9(1), 41–45 (2004).

Zelle-Rieser, C. et al. T cells in multiple myeloma display features of exhaustion and senescence at the tumor site. J Hematol. Oncol. 9(1), 116 (2016).

Romagnani, S. Th1/Th2 cells. Inflamm. Bowel. Dis. 5(4), 285–294 (1999).

Otsuki, T. et al. IL-10 in myeloma cells. Leuk. Lymphoma 43(5), 969–974 (2002).

Hong, S. et al. Roles of idiotype-specific t cells in myeloma cell growth and survival: Th1 and CTL cells are tumoricidal while Th2 cells promote tumor growth. Cancer Res. 68(20), 8456–8464 (2008).

Prabhala, R. H. et al. Elevated IL-17 produced by TH17 cells promotes myeloma cell growth and inhibits immune function in multiple myeloma. Blood 115(26), 5385–5392 (2010).

Caers, J. et al. Neighboring adipocytes participate in the bone marrow microenvironment of multiple myeloma cells. Leukemia 21(7), 1580–1584 (2007).

Favaloro, J. et al. Myeloid derived suppressor cells are numerically, functionally and phenotypically different in patients with multiple myeloma. Leuk. Lymphoma 55(12), 2893–2900 (2014).

Yi, Z. et al. The yin-yang effects of immunity: From monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance to multiple myeloma. Front. Immunol. 13, 925266 (2022).

Giallongo, C. et al. CXCL12/CXCR4 axis supports mitochondrial trafficking in tumor myeloma microenvironment. Oncogenesis 11(1), 6 (2022).

Yang, Y. et al. CXCL12-CXCR4/CXCR7 axis in cancer: From mechanisms to clinical applications. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 19(11), 3341–3359 (2023).

Lee, N. H., Nikfarjam, M. & He, H. Functions of the CXC ligand family in the pancreatic tumor microenvironment. Pancreatology 18(7), 705–716 (2018).

Xiang, X. et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts: Vital suppressors of the immune response in the tumor microenvironment. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 67, 35–48 (2022).

Bagheri, H. et al. CXCL-10: A new candidate for melanoma therapy?. Cell Oncol. (Dordr) 43(3), 353–365 (2020).

Watanabe, T. et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced CXCL10 mRNA level and six stimulant-mRNA combinations in whole blood: Novel biomarkers for bortezomib responses obtained from a prospective multicenter trial for patients with multiple myeloma. PLoS ONE 10(6), e0128662 (2015).

Ullah, T. R. The role of CXCR4 in multiple myeloma: Cells’ journey from bone marrow to beyond. J. Bone. Oncol. 17, 100253 (2019).

Hernandez-Ruiz, M. et al. Cxcl17(-/-) mice develop exacerbated disease in a T cell-dependent autoimmune model. J. Leukoc. Biol. 105(5), 1027–1039 (2019).

Choreno-Parra, J. A. et al. The protective and pathogenic roles of CXCL17 in human health and disease: Potential in respiratory medicine. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 53, 53–62 (2020).

Merz, M. et al. Bispecific antibodies targeting BCMA or GPRC5D are highly effective in relapsed myeloma after CAR T-cell therapy. Blood Cancer J. 14(1), 214 (2024).

Zamagni, E. et al. Anti-CD38 and anti-SLAMF7: The future of myeloma immunotherapy. Expert Rev. Hematol. 11(5), 423–435 (2018).

Park, M. S. et al. Importance of circulating tumor DNA analysis at diagnosis in early triple-negative breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer 32(2), 416–425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12282-025-01673-y (2025).

Cao, K. et al. Pan-cancer analysis of UBE2T with a focus on prognostic and immunological roles in lung adenocarcinoma. Respir. Res. 23(1), 306 (2022).

Zhang, W. et al. High expression of UBE2T predicts poor prognosis and survival in multiple myeloma. Cancer Gene. Ther. 26(11–12), 347–355 (2019).

Khan, M. et al. A novel necroptosis-related gene index for predicting prognosis and a cold tumor immune microenvironment in stomach adenocarcinoma. Front. Immunol. 13, 968165 (2022).

Chen, S. N. et al. E2F2 modulates cell adhesion through the transcriptional regulation of PECAM1 in multiple myeloma. Br. J. Haematol. 202, 804 (2023).

Gioia, M. et al. Exo1 protects DNA nicks from ligation to promote crossover formation during meiosis. PLoS Biol. 21(4), e3002085 (2023).

Shinozuka, K. et al. Impact of polymorphic variations of gemcitabine metabolism, DNA damage repair, and drug-resistance genes on the effect of high-dose chemotherapy for relapsed or refractory lymphoid malignancies. Biol. Blood Marrow Transp. 22(5), 843–849 (2016).

Berge, T. et al. SH2D2A modulates T cell mediated protection to a B cell derived tumor in transgenic mice. PLoS ONE 7(10), e48239 (2012).

Yunhan Wang, Y. et al. High expression of CDca7 in the prognosis of glioma and its relationship with ferroptosis and immunity. Genes 14(7), 1406. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes14071406 (2023).

Wallington-Beddoe, C. T. & Mynott, R. L. Prognostic and predictive biomarker developments in multiple myeloma. J. Hematol. Oncol. 14(1), 151 (2021).

Poos, A. M. et al. Resolving therapy resistance mechanisms in multiple myeloma by multiomics subclone analysis. Blood 142(19), 1633–1646 (2023).

Maura, F. et al. Genomic classification and individualized prognosis in multiple myeloma. J. Clin. Oncol. 42(11), 1229–1240 (2024).

Hagen, P., Zhang, J. & Barton, K. High-risk disease in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: Beyond the R-ISS and IMWG definitions. Blood Cancer J. 12(5), 83 (2022).

D’Agostino, M. et al. Second revision of the international staging system (R2-ISS) for overall survival in multiple myeloma: A European Myeloma Network (EMN) Report Within the HARMONY Project. J. Clin. Oncol. 40(29), 3406–3418 (2022).

Zhong, L. et al. Exploring the R-ISS stage-specific regular networks in the progression of multiple myeloma at single-cell resolution. Sci. China Life Sci. 65(9), 1811–1823 (2022).

Yu, Z. et al. Characterization and application of a lactate and branched chain amino acid metabolism related gene signature in a prognosis risk model for multiple myeloma. Cancer Cell Int. 23(1), 169 (2023).

Sun, F. et al. A gene signature can predict risk of MGUS progressing to multiple myeloma. J. Hematol. Oncol. 16(1), 70 (2023).

Min, R., Hu, Z. & Zhou, Y. Identifying the prognostic significance of mitophagy-associated genes in multiple myeloma: A novel risk model construction. Clin. Exp. Med. 24(1), 249 (2024).

Guillerey, C. et al. Immune responses in multiple myeloma: role of the natural immune surveillance and potential of immunotherapies. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 73(8), 1569–1589 (2016).

Soekojo, C. Y. & Chng, W. J. Treatment horizon in multiple myeloma. Eur. J. Haematol. 109(5), 425–440 (2022).

Colombo, F. et al. In vitro models of the crosstalk between multiple myeloma and stromal cells recapitulate the mild NF-κB activation observed in vivo. Cell Death Dis. 15(10), 731 (2024).

Ahmadi, P. et al. T cell redirection as a new standard of care for relapsed multiple myeloma: Impact on inpatient capacity, financial burden and infrastructural requirements in Germany. Bone Marrow Transplant. 60(4), 538–540. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-024-02505-x (2025).

Todoerti, K. et al. DIS3 mutations in multiple myeloma impact the transcriptional signature and clinical outcome. Haematologica 107(4), 921–932 (2022).

Manfrini, N. et al. FAM46C and FNDC3A are multiple myeloma tumor suppressors that act in concert to impair clearing of protein aggregates and autophagy. Cancer Res. 80(21), 4693–4706 (2020).

Rooney, M. S. et al. Molecular and genetic properties of tumors associated with local immune cytolytic activity. Cell 160(1–2), 48–61 (2015).

Gibney, G. T., Weiner, L. M. & Atkins, M. B. Predictive biomarkers for checkpoint inhibitor-based immunotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 17(12), e542–e551 (2016).

McGranahan, N. et al. Clonal neoantigens elicit T cell immunoreactivity and sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade. Science 351(6280), 1463–1469 (2016).

Choi, T. Y. et al. BK channel blocker paxilline attenuates thalidomide-caused synaptic and cognitive dysfunctions in mice. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 17653 (2018).

Acknowledgements