Abstract

Functional constipation (FCon) is a prevalent common functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) frequently linked to mental and psychological disorders. Although previous studies have demonstrated alterations in brain structure and function in FCon, there remains a lack of investigation into the network-level structural inter-relationships (e.g., structural covariance) within key regions such as the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC). This study aimed to investigate whether gray matter volume (GMV) covariance in OFC subregions is selectively disrupted in FCon patients. A cohort of 87 patients with FCon and 87 healthy controls (HC) underwent high-resolution structural MRI scans. The GMV covariance was analyzed using voxel-based morphometry, and the covariance patterns between OFC subregions and other brain regions were examined using a general linear model. FCon patients demonstrated selective alterations in GMV covariance, notably within the lateral and medial OFC subregions, which showed altered covariance with brain regions associated with sensory, motor, and cognitive control functions, including the olfactory cortex, supplementary motor area, insula, and superior frontal gyrus. Our findings indicate that FCon patients show specific GMV covariance alterations in the OFC subregions, suggesting that these structural changes may be associated with disrupted brain–gut interactions and gastrointestinal dysfunction in patients with functional constipation, though the complex and bidirectional nature of gut–brain communication warrants further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Functional constipation (FCon) is a common functional gastrointestinal disorder (FGIDs), characterized by infrequent or difficult bowel movements, often accompanied by symptoms such as bloating, abdominal pain, and a sensation of incomplete evacuation1,2,3. According to the Rome IV criteria, FCon is diagnosed based on specific symptom-based guidelines, including fewer than three defecations per week, straining during defecation, or a sensation of anorectal obstruction. The global prevalence of FCon varies widely, with estimates ranging from 0.7 to 79%, and an average prevalence of approximately 16% in adults4,5. In addition to gastrointestinal discomfort, many FCon patients experience comorbid mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety6,7, which exacerbate their symptoms and lower their quality of life. The chronic nature of FCon imposes a substantial economic burden on healthcare systems and reduces social productivity8,9. Despite its high prevalence and significant impact, the exact pathophysiological mechanisms underlying FCon remain unclear, presenting challenges for developing effective treatments strategies.

In recent years, multimodal neuroimaging techniques, including structural magnetic resonance imaging (sMRI)10, resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI)11,12,13, and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI)14, have provided novel insights into the neural mechanisms of FCon. These studies have demonstrated that FCon is associated with both functional and structural changes in the brain, particularly in regions involved in sensory processing, emotional regulation, and motor control11,12. For instance, rs-fMRI studies have shown altered functional connectivity in brain networks such as the salience network, sensorimotor network, and default mode network13. Structural MRI studies have revealed reduced GMV in several brain regions, including the thalamus, anterior insula, and prefrontal cortex15. These findings suggest that FCon may result from disruptions in the microbiota-gut-brain (MGB) axis, where abnormal brain activity contributes to gastrointestinal dysfunction and mental health disorders16. It is possible that FCon induces both functional and structural anomalies in the brain through the MGB axis, further exacerbating psychological and gastrointestinal symptoms7,17.

The orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) plays a crucial role in decision-making, emotional processing, and reward evaluation18,19,20. Neuroimaging studies in FCon patients have suggested that the OFC, along with its connections to the insula, cingulate gyrus, amygdala, hypothalamus and thalamus, may be involved in the altered processing of visceral signals21. Notably, irritable bowel syndrome patients (IBS) exhibit GMV reductions in the medial OFC, ventromedial and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, anterior insula, cingulate cortex and hippocampus, suggesting shared neural disruptions in emotion regulation and cognitive control across FGIDs22. Additionally, white matter changes in IBS include decreased connectivity in sensory-processing tracts (thalamus, insula, cingulum, fornix)23. Functional changes in functional dyspepsia (FD) further highlight disruptions in pain and salience networks, including the frontal cortex, insula, anterior cingulate cortex, thalamus, hippocampus, and amygdala24. These findings suggest that alterations in the OFC and its associated networks may be part of a broader neurobiological mechanism underlying FGIDs. However, the OFC is not a homogeneous structure; it is composed of several subregions, each with distinct functional roles25,26. For instance, the medial OFC is primarily involved in the evaluation of rewards and affective processing27, while the lateral OFC is associated with the suppression of negative emotions and behavioral control28. Gray matter volume (GMV) covariance is an established method to describe the topology of the brain, reflecting anatomical and functional connectivity changes mediated by the development of axonal connections29,30,31,32. Recently, our group have demostrated that the OFC shows selective subregional structural alterations in FCon patients15. Therefore, we propose a hypothesis that specific OFC subregions may show altered GMV covariance, indicating their distinct role in FCon pathophysiology. Using structural MRI, we investigate the covariance patterns between OFC subregions and other brain regions to explore whether the GMV covariance of these subregions is selectively disrupted in FCon patients. This study aims to provide a more refined understanding of the structural covariance alterations within specific OFC subregions in FCon patients. Given the OFC’s critical role in visceral signal processing, emotional regulation, and sensory integration, our findings may offer new insights into how alterations in OFC connectivity patterns relate to the gut-brain axis in FCon.

Methods and materials

Participants

A total of 93 patients ranges from 18 to 70 years diagnosed with functional constipation based on the Rome IV criteria were recruited from Shanghai Ten People’s Hospital, along with 91 healthy controls (HCs) from the local community matched for age and sex. The exclusion criteria included neurological or psychiatric disorders, brain lesions, and contraindications for MRI scanning. Specific exclusion criteria were: (1) MRI contraindications; (2) left-handedness; (3) organic intracranial lesions; (4) history of head trauma, alcoholism, drug abuse or psychiatric diagnosis; (5) suboptimal image quality; and (6) pregnant or lactating women. Six FCon patients were excluded from the study. Among them, two were excluded due to suboptimal image quality, one due to an intracranial lesion (meningioma), and three due to dental implants. Similarly, four HCs were excluded, including three for poor image quality and one for dental implants. Ultimately, the final study sample consisted of 87 FCon patients and 87 HCs. The experiment was approved by the Ethical Committee of Shanghai Tenth People’s Hospital (23KN16) and was conducted according to the declaration of Helsinki, and each participant signed an informed consent form prior to the participation.

Clinical assessment

Patients with FCon have completed series of self-administered questionnaires designed to comprehensively evaluate constipation severity, its impact on daily activities, and overall mental health status. These assessments included: (i) the Wexner constipation score, which measures frequency of defecation, sensation of incomplete evacuation, abdominal pain or bloating, the difficulty of defecation, and duration of symptoms; (ii) the Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality of Life (PAC-QOL) scale, which evaluates how constipation affects daily life33; (iii) the ZUNG Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS)34 and the ZUNG Self-Rating Depressive Scale (SDS)35, both of which assess the severity of anxiety and depression. The healthy control (HC) group also completed the SAS and SDS questionnaires.

MRI data acquisition and preprocessing

Structural MRI images were acquired using a 3.0-Tesla Ingenia scanner (Philips) equipped with a 32-channel head coil. To minimize noise, cotton balls and earplugs were provided, while foam pads were used to reduce head movement. T1-weighted sagittal images were acquired using the turbo field echo (TFE) sequence with the imaging parameters: repetition time (TR) = 7.0 ms; echo time (TE) = 3.2 ms; matrix = 256 × 256; field of view (FOV) = 256 × 256 mm2; flip angle (FA) = 12°; slice thickness = 1.0 mm with no interslice gap; and a total of 192 slices.

Gray matter volume calculation

All structural MRI images were preprocessed using CAT12 software (version r1364, http://dbm.neuro.uni-jena.de/cat) following a standardized workflow. The preprocessing steps included bias correction, tissue segmentation, and spatial normalization with Diffeomorphic Anatomical Registration Through Exponentiated Lie Algebra (DARTEL) algorithms. Afterward, Jacobian modulation was applied to preserve the total amount of gray matter volume, generating normalized and modulated gray matter maps for each participant. These maps were then smoothed using an 8 × 8 × 8mm3 full-width at half maximum (FWHM) Gaussian kernel.

GMV covariance alterations pattern of OFC subregions

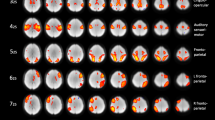

On the basis of the human Brainnetome Atlas36, the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) was automatically divided into 6 subregions in each hemisphere (Fig. 1): OrG_6_1, OrG_ 6_2, OrG_ 6_3, OrG_ 6_4, OrG_6_5, OrG_6_6 bilaterally. For each OFC subregion, we extracted the mean GMV of each OFC subregion. Additionally, we calculated total intracranial volume (TIV) as a global measure to control for individual differences in brain size. The GMV covariance patterns of OFC subregions were then computed based on previously established method29,37,38. This method is sensitive to interregional anatomical correlations and has been successfully used to investigate similar neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders32, thereby offering a novel perspective on the structural underpinnings of FCon.

Using the SPM12 toolbox in MATLAB, a voxel-wise permutation-based non-parametric linear regression model was conducted to identify the potential differences in covariance between the GMV of the OFC subregions and each cerebral voxel between FCon patients and HCs, with age, sex, and TIV included as covariates (Eq. 1):

Then, we applied threshold-free cluster enhancement (TFCE) combined with family-wise error (FWE) correction to control for multiple comparisons (P < 0.05, corrected). TFCE enhances signal detection by integrating both cluster extent and voxel-wise intensity, without requiring an arbitrary cluster-forming threshold39. Statistical significance was determined using permutation testing, ensuring robust correction for multiple comparisons. Furthermore, to interpret the direction of disrupted GMV covariance in the OFC subregions, a two-sample t-test was used to compare the mean GMV differences between FCon patients and HCs in each OFC subregion. (P < 0.05, Bonferroni correction). This analysis allowed us to determine whether the regions showing altered GMV covariance exhibited a common increase or decrease in GMV across groups.

Illustration of the specific locations of different orbitofrontal cortex subregions. The image was created using MRIcroGL software (version 1.2.20211006; https://www.nitrc.org/projects/mricrogl). Abbreviations: L, left; OrG, orbital gyrus; R, right.

Target region definition and revealing subregion-specific covariance disruption patterns

To identify the specific covariance disruption patterns in OFC subregions for FCon patients, we focused on brain region of interest (ROIs) that showed altered covariance in at least one OFC subregion. The analysis followed these steps: (1) For each OFC subregion’s statistic map, we created a binary mask indicating regions where there were significant group differences in GMV covariance between that subregion and other brain voxels; (2) The binary masks from all OFC subregions were then combined to form a whole mask; (3) We determined the intersection between this whole mask and each region in the Anatomical Labelling Atlas 3 (AAL3)40; (4) Then the overlapping ratio between these intersection voxels and each ALL3 region were calculated; (5) Target ROIs were identified based on two criteria: an overlapping ratio bigger than 15% and the overlapping volume exceeding 1mm3; (6) Finally, the mean GMV value of identified ROIs were extracted. To visualize the unique disrupted structural covariance patterns across OFC subregions in FCon, we created a radar chart.

Association between the GMV covariance and clinical features

The clinical assessments included the Wexner constipation score, PAC-QOL, SAS and SDS. Spearman correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between GMV covariance changes and these clinical variables in FCon patients with age and sex as covariates using SPSS version 22. (P < 0.05, uncorrected). Multiple comparison correction was not applied due to the exploratory nature of the analysis and the limited sample size, and results were interpreted accordingly.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

The demographic and clinical characteristics of FCon patients and healthy controls were summarized in Table 1. There were no significant differences in gender distribution between the groups (χ2 = 0.096, P = 0.106), and only a slight difference in age (F = 6.837, P = 0.010). In contrast, FCon patients showed markedly higher BMI (F = 28.53, P < 0.001), as well as significantly elevated levels of depression (F = 14.81, P < 0.001) and anxiety (F = 32.79, P < 0.001) compared to healthy controls.

Altered GMV covariance patterns of OFC subregions in FCon

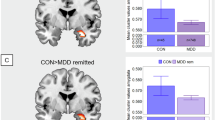

We observed significantly increased GMV covariance patterns in four OFC subregions for FCon patients, including the OrG_L_6_2, OrG_L_6_3, OrG_L_6_4 and OrG_R_6_4 (P < 0.05, TFCE-FWE correction). These subregions consistently showed elevated GMV covariance with several regions, including the bilateral olfactory cortex, amygdala, superior frontal gyrus, inferior frontal gyrus and insula (Fig. 2). Specifically, the left OrG_6_2, corresponding to the orbital area 12/47, exhibited increased GMV covariance with the left triangular part of the inferior frontal gyrus, bilateral olfactory cortex, left supplementary motor area, paracentral lobule, and putamen. The left OrG_6_3, representing the lateral area 11, showed enhanced GMV covariance with the bilateral olfactory cortex. Additionally, the bilateral OrG_6_4, associated with the medial area 11, displayed distinct patterns: the left OrG_6_4 showed increased GMV covariance with the left Heschl gyrus and paracentral lobule, whereas the right OrG_6_4 showed enhanced GMV covariance with the left superior frontal gyrus, right olfactory cortex, and left putamen.

Altered GMV covariance patterns of the four OFC subregions in FCon patients. The color bar indicates the intensity of altered GMV covariance in FCon patients (t-value). The image was created using BrainNet Viewer (version 1.7; https://www.nitrc.org/projects/bnv/). Abbreviations: L, left; OrG, orbital gyrus; R, right.

Furthermore, two-sample t-tests also revealed a significant decrease in GMV in FCon patients across these four OFC subregions (P < 0.05, Bonferroni correction) (Fig. 3).

Specific differential GMV covariance patterns of OFC subregions

Based on the target ROIs defined in the methods section, we selected a total of 20 regions, including the left amygdala (AMYG), left caudate (CAU), left Heschl gyrus (HES), left triangular parts of the inferior frontal gyrus (IFGtri), bilateral insular cortex (INS), bilateral olfactory cortex (OLF), right precentral gyrus (PCG), bilateral precuneus (PCUN), left paracentral lobule (PCL), left putamen (PUT), bilateral dorsal part of superior frontal gyrus (SFGdor), left supramarginal gyrus (SMG) and left superior temporal gyrus (STG).

To visualize the unique GMV covariance patterns of each OFC subregion, we created GMV covariance radar charts by comparing each OFC subregion and the 20 selected ROIs (Fig. 4). Compared to the HC group, the OrG_L_6_2 in FCon patients showed primarily increased covariance with bilateral olfactory cortex (OLF) and left putamen (PUT); OrG_L_6_3 exhibited stronger covariance with the bilateral OLF and right amygdala (AMYG); OrG_L_6_4 displayed greater covariance mainly with the left paracentral lobule (PCL); and OrG_R_6_4 showed elevated covariance with the left Heschl gyrus (HES) and left dorsal superior frontal gyrus (SFGdor).

The different GMV covariance fingerprints of the four OFC subregions in FCon patients. Abbreviations: AMGY: amygdala; CAU: caudate nucleus; HES, Heschl gyrus; INS, insular cortex; L, left; OLF, olfactory cortex; OrG, Orbital gyrus; PCG, precentral gyrus; PCL, paracentral lobule; PCUN, precuneus; PUT, putamen; R, right; SFGdor, dorsal part of superior frontal gyrus; SMG, supramarginal gyrus; STG, superior temporal gyrus.

Association between the GMV covariance and clinical information

Spearman correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between GMV covariance alteration and the clinical data in FCon patients. There was a weak positive correlation between the SAS score with the GMV covariance between OrG_R_6_4 and SFGdor_L (r = 0.181, P = 0.049, uncorrected). Similarly, the PAC-QOL score showed a positive correlation with the GMV covariance between OrG_R_6_4 and SFGdor_L (r = 0.204, P = 0.031, uncorrected). No significant association were found between the GMV covariance patterns of OFC subregions and SDS or Wexner constipation scores.

Discussion

The study is the first to identify selective disruptions in GMV covariance within specific subregions of the OFC in patients with Fcon. Our findings emphasize the complex role that OFC subregions play in coordinating interactions between cortical and subcortical areas, suggesting potential disruptions in the integration of sensory and emotional processes of FCon. Notably, increased GMV covariance was observed in several OFC subregions, potentially indicating abnormal structural co-variation with brain regions involved in sensory, motor, and cognitive functions. These insights provide a deeper understanding of how OFC subregions may influence the pathological mechanisms underlying FCon.

Our study uncovered distinct GMV covariance patterns in various OFC subregions among FCon patients. Specifically, the left OrG_6_2, mainly located in the orbital area 12/4741, exhibited increased GMV covariance with several regions, including the left triangular parts of the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), bilateral olfactory cortex, left supplementary motor area (SMA), paracentral lobule, and putamen. This pattern suggests that OrG_6_2 is involved in a network integrating sensory and motor functions12. The triangular part of the IFG is linked to language processing, executive function, and decision-making42, while the SMA and paracentral lobule play key roles in motor control43. The heightened covariance with these regions may represent a compensatory mechanism in response to deficits in motor control or sensory processing in FCon patients44. Previous research has indicated that the SMA and paracentral lobule are critical for initiation and execution motor tasks, including those related to pelvic floor and sphincter control45. The observed alterations might reflect an adaptive response to disrupted autonomic or sensory feedback in FCon patients, which could contribute to the abnormal defecation and bowel habits commonly reported in these individuals10.

The left OrG_6_3, primarily located in the lateral area 1141, showed enhanced GMV covariance with the bilateral olfactory cortex. This connection is particularly noteworthy because both the OFC and olfactory cortex are key regions for processing sensory information, especially in relation to smell and taste46. The OFC plays a crucial role in evaluating sensory stimuli and making reward-related decisions47. The heightened GMV covariance with the olfactory cortex observed in FCon patients may reflect altered sensory processing or increased sensitivity to visceral signals, which could impact their perception of bodily sensations and contribute to disrupted gut-brain communication48. Such heightened sensitivity, often termed visceral hypersensitivity, is a hallmark of functional gastrointestinal disorders49. Alterations within these sensory networks could lead to an exaggerated perception of abdominal discomfort or pain, potentially worsening constipation symptoms in affected individuals.

In contrast, the bilateral OrG_6_4 subregions, located in the medial area 1141, exhibited more widespread GMV covariance changes. The left OrG_6_4 showed increased covariance with the left Heschl gyrus and paracentral lobule, while the right OrG_6_4 presented the most extensive covariance alterations, involving the left dorsal superior frontal gyrus (SFGdor), right olfactory cortex, and left putamen. This suggest that the right OrG_6_4 might play a more significant role in integrating sensory and motor information in FCon patients, potentially impacting higher-order cognitive processes such as attention, decision-making, and motor planning50. The SFG, as part of the prefrontal cortex, is involved in executive functions like working memory and attentional regulation51, while the putamen, a core component of the basal ganglia, is critical for motor control and habit formation52. These altered connections may reflect disrupted cognitive control over habitual or reflexive behaviors, such as the urge to defecate or sphincter relaxation-potentially contributing to the chronic constipation observed in FCon patients.

The weak positive correlation between the SAS score and GMV covariance between the right OrG_6_4 and left SFGdor suggests that anxiety may impact the structural connectivity patterns in FCon patients. This observation is consistent with previous research indicating that anxiety is a common comorbidity in FCon and can exacerbate symptoms through its influence on brain-gut interactions53. However, multiple comparison correction was not applied, and caution is required when interpreting the statistical significance of these findings. Similarly, the positive relationship between the PAC-QOL score and the GMV covariance in the same regions further underscores the clinical relevance of these structural connectivity changes. However, despite significant alterations in OFC GMV covariance, we found no direct correlation between these changes and constipation symptom scores. This may be due to the complex and multifactorial nature of FCon, where psychological comorbidities (e.g., anxiety and depression), other brain network disruptions, and individual variability in symptom perception contribute to symptom severity6,7. Additionally, the OFC is involved in broader functions, such as decision-making and emotional regulation18,19,20, which may not directly correspond with constipation-related symptomatology. These findings emphasize the need to consider both psychological and physiological factors in the management of FCon and highlight the importance of further research to elucidate the underlying neurobiological mechanisms and their clinical implications.

The selective GMV covariance changes identified in OFC subregions suggest a potential disruption in the balance between cortical and subcortical networks in FCon patients, likely reflecting disruptions in the brain-gut axis. The brain-gut axis, a bidirectional communication pathway linking the central nervous system with the gastrointestinal tract, plays a key role in maintaining gut homeostasis and regulating visceral sensitivity49. The interplay between brain structure, emotions, and constipation symptoms in FCon likely reflects a bidirectional relationship mediated by the gut-brain axis. Dysregulation of this axis has been implicated in the pathogenesis of functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs), altering the way visceral are processed and perceived, and contributing to the experience of abdominal pain54. Chronic constipation and altered gut motility can induce maladaptive brain plasticity via gut microbiota dysbiosis, neuroinflammation, and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis hyperactivity55. Conversely, anxiety and depression may contribute to brain structural changes in FCon by elevating stress-related neuroendocrine activity53. HPA axis dysregulation leads to increased cortisol levels, affecting gray matter volume and connectivity in key regions like the OFC, amygdala, and hippocampus56. The observed correlation between SAS scores and OFC-SFG connectivity suggests that anxiety may exacerbate these brain changes, influencing both sensory processing and emotional regulation. These findings support the idea that brain changes, emotions, and gut dysfunction interact dynamically, rather than following a simple causal pathway.

Our findings hold significant clinical relevance for advancing the understanding of the neurobiological mechanisms underlying FCon and informing the development of targeted treatment strategies. The identification of specific OFC subregions with altered GMV covariance patterns suggests that these regions could potentially serve as biomarkers for diagnosing FCon or tracking treatment efficacy. However, this study has some limitations. First, the correlation analysis was conducted only in FCon patients, which may introduce selection bias and limit generalizability. Additionally, we did not correct for multiple comparisons in the correlation analysis due to the exploratory nature of the study and the limited sample size. Second, despite matching group-level sex distributions, female predominance (~ 73% FCon cohort) may confound results given sex-specific gut-brain axis modulation. Future research should stratify by sex, replicate these analyses in larger, more diverse samples, including both patients and healthy controls, while implementing stricter statistical corrections, and focus on exploring the causal links between anxiety, altered OFC GMV covariance, and FCon symptoms through longitudinal studies. Additionally, employing multimodal neuroimaging techniques that combine functional and structural MRI could provide deeper insights into the complex interactions between the OFC and other brain networks in FCon.

In conclusion, this study reveals selective disruptions in GMV covariance within specific OFC subregions in FCon patients, indicating that these structural abnormalities may play a role in altered sensory processing and impaired motor control. The associations with anxiety and quality of life scores emphasize the importance of a comprehensive treatment approach that addresses both the psychological and physical dimensions of FCon to achieve better patient outcomes.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

Drossman, D. A. Functional Gastrointestinal disorders: History, pathophysiology, clinical features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology 19 (2016).

Black, C. J., Drossman, D. A., Talley, N. J., Ruddy, J. & Ford, A. C. Functional gastrointestinal disorders: Advances in understanding and management. Lancet 21(10263), 1664–1674 (2020).

Kilgore, A. & Khlevner, J. Functional constipation: Pathophysiology, evaluation, and management. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 60(Suppl 1), S20–S29 (2024).

Mugie, S. M., Benninga, M. A. & Di Lorenzo, C. Epidemiology of constipation in children and adults: A systematic review. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 25(1), 3–18 (2011).

Barberio, B., Judge, C., Savarino, E. V. & Ford, A. C. Global prevalence of functional constipation according to the Rome criteria: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 6(8), 638–648 (2021).

Hosseinzadeh, S. T., Poorsaadati, S., Radkani, B. & Forootan, M. Psychological disorders in patients with chronic constipation. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench Summer 4(3), 159–163 (2011).

Person, H. & Keefer, L. Psychological comorbidity in gastrointestinal diseases: Update on the brain-gut-microbiome axis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 20(107), 110209 (2021).

Martin, B. C., Barghout, V. & Cerulli, A. Direct medical costs of constipation in the United States. Manag Care Interface 19(12), 43–49 (2006).

Liem, O. et al. Health utilization and cost impact of childhood constipation in the united States. J. Pediatr. 154(2), 258–262 (2009).

Hu, C. et al. Cortical morphometry alterations in brain regions involved in emotional, motor-control and self-referential processing in patients with functional constipation. Brain Imaging Behav. 14(5), 1899–1907 (2020).

Zhu, Q. et al. Distinct resting-state brain activity in patients with functional constipation. Neurosci. Lett. 6(632), 141–146 (2016).

Jin, Q. et al. Sex-related differences in resting-state brain activity and connectivity in the orbital frontal cortex and Insula in patients with functional constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 31(5), e13566 (2019).

Yu, X. et al. Aberrant intrinsic functional brain networks in patients with functional constipation. Neuroradiology 65(2), 337–348 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. Functional constipation is associated with alterations in thalamo-limbic/parietal structural connectivity. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 33(12), e13992 (2021).

Cai, W. et al. Transcriptomic signatures associated with gray matter volume changes in patients with functional constipation. Front. Neurosci. 15, 791831 (2021).

Stilling, R. M., Dinan, T. G. & Cryan, J. F. Microbial genes, brain & behaviour - epigenetic regulation of the gut-brain axis. Genes Brain Behav. 13(1), 69–86 (2014).

Mayer, E. A., Naliboff, B. D. & Craig, A. D. Neuroimaging of the brain-gut axis: From basic understanding to treatment of functional GI disorders. Gastroenterology 131(6), 1925–1942 (2006).

Kringelbach, M. L. & Rolls, E. T. The functional neuroanatomy of the human orbitofrontal cortex: Evidence from neuroimaging and neuropsychology. Prog Neurobiol. 72(5), 341–372 (2004).

Kringelbach, M. L. The human orbitofrontal cortex: Linking reward to hedonic experience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6(9), 691–702 (2005).

Rolls, E. T. The orbitofrontal cortex and emotion in health and disease, including depression. Neuropsychologia 128, 14–43 (2019).

Price, J. L. Definition of the orbital cortex in relation to specific connections with limbic and visceral structures and other cortical regions. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 1121, 54–71 (2007).

Li, Z. et al. Irritable bowel syndrome is associated with brain health by neuroimaging, behavioral, biochemical, and genetic analyses. Biol. Psychiatry 15(12), 1122–1132 (2024).

Asadi Anar, M. et al. Alterations of fractional anisotropy and white matter integrity in irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of diffusion tensor imaging studies. Front. Neurosci. 18, 1426218 (2024).

Lee, I. S., Wang, H., Chae, Y., Preissl, H. & Enck, P. Functional neuroimaging studies in functional dyspepsia patients: A systematic review. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 28(6), 793–805 (2016).

Liu, H., Qin, W., Qi, H., Jiang, T. & Yu, C. Parcellation of the human orbitofrontal cortex based on gray matter volume covariance. Hum. Brain Mapp. 36(2), 538–548 (2015).

Ongur, D., Ferry, A. T. & Price, J. L. Architectonic subdivision of the human orbital and medial prefrontal cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. Jun. 2(3), 425–449 (2003).

Amodio, D. M. & Frith, C. D. Meeting of Minds: The medial frontal cortex and social cognition. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7(4), 268–277 (2006).

Seeley, W. W. et al. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. J. Neurosci. 28(9), 2349–2356 (2007).

Mechelli, A., Friston, K. J., Frackowiak, R. S. & Price, C. J. Structural covariance in the human cortex. J. Neurosci. 7(36), 8303–8310 (2005).

Alexander-Bloch, A., Giedd, J. N. & Bullmore, E. Imaging structural co-variance between human brain regions. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14(5), 322–336 (2013).

Alexander-Bloch, A., Raznahan, A., Bullmore, E. & Giedd, J. The convergence of maturational change and structural covariance in human cortical networks. J. Neurosci. 13(7), 2889–2899 (2013).

Sebenius, I. et al. Structural MRI of brain similarity networks. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 26(1), 42–59 (2025).

Marquis, P., De La Loge, C., Dubois, D., McDermott, A. & Chassany, O. Development and validation of the patient assessment of constipation quality of life questionnaire. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 40(5), 540–551 (2005).

Zung, W. W. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics 12(6), 371–379 (1971).

Zung, W. W. A self-rating depression scale. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 12, 63–70 (1965).

Fan, L. et al. The human brainnetome atlas: A new brain atlas based on connectional architecture. Cereb. Cortex 26(8), 3508–3526 (2016).

Seeley, W., Crawford, R. K., Zhou, J., Miller, B. L. & Greicius, M. D. Neurodegenerative diseases target large-scale human brain networks. Neuron 16(1), 42–52 (2009).

Kelly, C. et al. A convergent functional architecture of the Insula emerges across imaging modalities. Neuroimage 16(4), 1129–1142 (2012).

Smith, S. M. & Nichols, T. E. Threshold-free cluster enhancement: Addressing problems of smoothing, threshold dependence and localisation in cluster inference. Neuroimage 1(1), 83–98 (2009).

Rolls, E. T., Huang, C. C., Lin, C. P., Feng, J. & Joliot, M. Automated anatomical labelling atlas 3. Neuroimage 1(206), 116189 (2020).

Mackey, S. & Petrides, M. Quantitative demonstration of comparable architectonic areas within the ventromedial and lateral orbital frontal cortex in the human and the macaque monkey brains. Eur. J. Neurosci. 32(11), 1940–1950 (2010).

Heather Hsu, C. C. et al. Connections of the human orbitofrontal cortex and inferior frontal gyrus. Cereb. Cortex 1(11), 5830–5843 (2020).

Wolpert, D. M. & Landy, M. S. Motor control is decision-making. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 22(6), 996–1003 (2012).

Zhao, J., Gregersen, T., Fassov, J., Krogh, K. & Gregersen, H. Implications of rectal preconditioning for interpretation of sensory-motor data. J. Biomech. 23(99), 109541 (2020).

Neshatian, L. et al. Alterations in brain activation patterns in women with functional defecatory disorder: A novel fMRI rectal balloon expulsion study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 34(12), e14389 (2022).

Rolls, E. T. The functions of the orbitofrontal cortex. Brain Cogn. 55(1), 11–29 (2004).

Pauli, W. M., Hazy, T. E. & O’Reilly, R. C. Expectancy, ambiguity, and behavioral flexibility: Separable and complementary roles of the orbital frontal cortex and amygdala in processing reward expectancies. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 24(2), 351–366 (2012).

Bienenstock, J., Kunze, W. A. & Forsythe, P. Disruptive physiology: Olfaction and the microbiome-gut-brain axis. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 93(1), 390–403 (2018).

Vanuytsel, T., Bercik, P. & Boeckxstaens, G. Understanding neuroimmune interactions in disorders of gut-brain interaction: From functional to immune-mediated disorders. Gut 72(4), 787–798 (2023).

Rich, E. L., Stoll, F. M. & Rudebeck, P. H. Linking dynamic patterns of neural activity in orbitofrontal cortex with decision making. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 49, 24–32 (2018).

Friedman, N. P. & Robbins, T. W. The role of prefrontal cortex in cognitive control and executive function. Neuropsychopharmacology 47(1), 72–89 (2022).

Krentzel, A. A. & Meitzen, J. Biological sex, estradiol and striatal medium spiny neuron physiology: A mini-review. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 12, 492 (2018).

Moloney, R. D. et al. Stress and the microbiota-gut-brain axis in visceral pain: Relevance to irritable bowel syndrome. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 22(2), 102–117 (2016).

Mayer, E. A. & Tillisch, K. The brain-gut axis in abdominal pain syndromes. Annu. Rev. Med. 62, 381–396 (2011).

Morais, L. H. & Schreiber HLt, Mazmanian, S. K. The gut microbiota-brain axis in behaviour and brain disorders. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19(4), 241–255 (2021).

Danese, A. & McEwen, B. S. Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiol. Behav. 12(1), 29–39 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants who involved in the study. And each participant signed an informed consent form prior to the participation. We also thank the assistance from medical writers, proof-readers and editors.

Funding

This study was funded by the Project of Chongming Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality(CKY2024-22)and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82100698).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.S., L.L. and W.C. designed research; T.H., J.G., H.T. and W.C. performed research; T.H., J.G., H.T. and W.C. was involved in the clinical assessment; Q.S., L.L. and J.Y. processed part of data; W.C., H.T. and J.Y. provided guidance and advice; Q.S., L.L. and J.Y. analyzed data; Q.S., L.L. and W.C. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Su, Q., Liu, L., Hua, T. et al. Selective disruption of gray matter volume covariance in orbitofrontal cortex subregions among patients with functional constipation. Sci Rep 15, 15440 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00148-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00148-6