Abstract

Extra-large HDL molecules (average diameter 14.3 nm) were inversely associated with preeclampsia. Additionally, extremely (particle diameters from 75 nm upwards) and very large (average diameter 64 nm) VLDL metabolites were associated with an increased the risk of preeclampsia. These findings provide evidence of molecules of interest for establishing risk or developing potential therapeutic targets" to "Specifically, extra-large HDL molecules (average diameter 14.3 nm) were inversely associated with preeclampsia, whereas extremely large (≥75 nm) and very large (average diameter 64 nm) VLDL metabolites were associated with an increased risk. These findings highlight distinct lipoprotein-related metabolic signatures linked to preeclampsia and suggest potential targets for risk assessment and therapeutic intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Preeclampsia is pregnancy-specific condition with detrimental effects on both the pregnant person and the fetus. Globally, preeclampsia complicates 5–8% of all pregnancies, ranking as a leading cause of maternal mortality, especially in middle- and low-income countries1,2.

Despite being recognized for decades, its pathophysiology is not completely understood, and efforts to identify biomarkers for risk estimation, early diagnosis, or complications prediction have proven ineffective. Consequently, prevention strategies are notably deficient3. The only cure for preeclampsia is delivery, which poses risks related to premature delivery for both mothers and newborns4. Therefore, it is critical to continue to understand the etiopathology of the disease.

Preeclampsia results from a combination of placental factors5,6, maternal–fetal immune dysfunction7, and maternal cardiometabolic factors8, and is classically characterized by maternal hypertension, proteinuria, after 20th week of pregnancy and other end-organ damage in the mother.

Metabolomics, the profiling of intermediate metabolites, is emerging as a crucial platform for understanding the mechanisms underlying human diseases. Given that preeclampsia is a complex condition, utilizing new technologies is necessary to improve understanding of the biological pathways underlying disease. Recently, research on metabolomic profiles or fingerprints in pregnant women (via targeted and untargeted metabolomics) has begun to elucidate the type and effect of various small-sized metabolites associated with preeclampsia. However, studies often have small sample sizes and findings are highly heterogeneous9. From this context, we aimed to determine the metabolomic profile associated with preeclampsia and its subtypes (i.e., early-onset preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome) in a cohort of pregnant women in Colombia.

Results

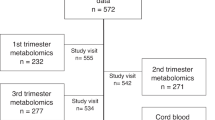

596 serum samples from pregnant women were included in the study (357 controls and 239 cases) (Fig. 1). Among women with preeclampsia, 65 women presented HELLP syndrome and 58 women developed preeclampsia before the 34th week of gestation. Significant differences were found in age, recruitment city, race, smoking in current pregnancy, initial and final weight, and gestational age between cases and controls (Table 1).

Metabolome-wide association study

For all preeclampsia, metabolites related to HDL size and extra-large HDL [HDL size: ORa 0.56 (95% CI 0.42–0.75) p = 7.1 × 10–5; XL-HDL-PL: ORa 0.56 (95% CI 0.42–0.75) p = 8.9 × 10–5; XL-HDL-L: ORa 0.57 (95% CI 0.43–0.76) p = 0.0001 XL-HDL-C: ORa 0.58 (95% CI 0.44–0.77) p = 0.0001; XL-HDL-CE: ORa 0.59 (95% CI 0.44–0.78) p = 0.0001] as well as PUFA/MUFA ratio [ORa 0.50 (95% CI 0.38–0.66) p = 9.0 × 10–7] and the ratio of polyunsaturated fatty acids to total fatty acids (PUFA%) [ORa 0.55 (95% CI 0.42–0.72) p = 2.7 × 10–5] showed inverse associations. The ratio of monounsaturated fatty acids to total fatty acids (MUFA%) was associated with a twofold increased risk of preeclampsia [ORa 2.32 (95% CI 1.71–3.12) p = 4.5 × 10–8] and glutamine showed a similar association [ORa 1.89 (95% CI 1.36–2.62), p = 0.0001], (Fig. 2A,B; Table S4).

Metabolome-wide association for preeclampsia, time of onset, and HELLP syndrome. (A) Multiple test p-value correction graph in preeclampsia. (B) Forest plot with metabolites associated with preeclampsia. (C) Multiple test for p-value correction graph in early-onset preeclampsia. (D) Forest plot with metabolites associated with early-onset preeclampsia. (E) Multiple test for p-value correction graph in HELLP syndrome. (F) Forest plot with metabolites associated with HELLP Syndrome. In (A, C, E) the red line represents the FDR-adjusted p-value threshold, and the green line represents the unadjusted p-value.

In the case of time of onset, a gradient of risk was observed for early-onset preeclampsia, particularly for Isoleucine (Fig. 2C,D, Tables 2, S4).

In HELLP syndrome, higher MUFA% was associated with an association of risk [ORa 5.17 (95% CI 2.55–10.5) p = 5.2 × 10–6]. However, PUFA% [ORa 0.28 (95% CI 0.14–0.54) p = 0.0001] and the PUFA/MUFA ratio [ORa 0.23 (95% CI 0.11–0.46) p = 2.8 × 10–5] were inversely associated with HELLP syndrome (Table S4, Fig. 2E–F).

Network analysis

The co-expression network analysis identified 7 highly interconnected metabolite modules (Table S5). The unadjusted module relationship showed that red module inversely correlated with all preeclampsia (β = − 0.21, p = 2.8 × 10–7), HELLP syndrome (β = − 0.12, p = 0.0044), and early-onset Preeclampsia (β = − 0.16, p = 6.4 × 10–5). Metabolites within this module corresponded to very-large (average diameter 14.3 nm) HDL molecules (XL-HDL-P, XL-HDL-L, XL-HDL-PL, XL-HDL-C, XL-HDL-CE, XL-HDL-FC).

Additionally, the green module was also inversely correlated with all preeclampsia (β = − 0.11, p = 3.43 × 10–3) and early-onset preeclampsia (β = − 0.11, p = 0.0036), while the turquoise module was inversely associated with HELLP syndrome (β = − 0.09, p = 0.01) (Fig. 3). The green module included large (average diameter 12.1 nm) HDL molecules (HDL SIZE, L-HDL-P, L-HDL-L, L-HDL-PL, L-HDL-C, L-HDL-CE, L-HDL-FC), and the turquoise module included subclasses of several lipoproteins of different sizes (VLDL, IDL, LDL), cholesterol, fatty acids, among others (Supplemental material—Table S6 shows complete list in turquoise module).

After adjustment for potential confounders (Table 3), the inverse association between modules and outcomes remained for the red (extra-large HDL metabolites) and green (large HDL metabolites) modules in all preeclampsia (Fig. 4A). However, these associations were not observed for HELLP syndrome (Fig. 4B), and early-onset preeclampsia (Fig. 4C). On the other hand, the brown and yellow module showed a risk association with all preeclampsia. Metabolites in brown module are related to VLDL markers, including extremely (particle diameters from 75 nm upwards), very (average diameter 64 nm) and large (average diameter 53.6 nm) sizes, (Supplemental material—Table S7 shows complete list in brown module). Metabolites in yellow module are related to fatty acids and triglycerides in VLDL, LDL and HDL markers (Supplemental material—Table S8 shows complete list in brown module).

Discussion

Main findings

This study examined the associations between serum metabolomic markers at the time of delivery assessed through proton NMR, and preeclampsia, time of onset, and HELLP syndrome among Colombian pregnant women. An association was observed between very large HDL molecules and reduced odds for all preeclampsia. On the other hand, we also found a risk association between elevated levels of MUFA% (in the MWAS approach) and disturbances in several VLDL particles with all preeclampsia (in the WGCNA analysis).

The role of HDL, as well as the role of other lipids, in pregnant women using non-metabolomic techniques, has been previously described10. Several meta-analyses have consistently reported an inverse association between HDL and preeclampsia [Weighted mean difference in HDL levels: − 0.33 mg/dL (95% CI − 0.59, − 0.08, p = 0.011)11, − 8.86 mg/dL (95% CI − 11.50, − 6.21)12, and − 2.1 mg/dL (95% CI − 3.5, − 0.8)13].

Metabolomics studies in preeclampsia, especially during the third trimester, have shown similar findings regarding HDL subclasses. Stadler et al.14 reported that women with preeclampsia had reduced levels of large and cholesterol-rich HDL, especially in those with early-onset preeclampsia. Dysfunction in the antioxidant activity of HDL has also been described in women with preeclampsia, marked by reduced activity of the enzyme PON1 and increased release of APO AI15. These changes seem to be present even from the second trimester16. These findings suggest that HDL levels may have a protective causal effect, and if they do, they should also be present from the first trimester. Recently, a two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) study examined the role of lipid traits in preeclampsia in four ancestry groups. This analysis showed that higher HDL-C levels were associated with a decreased risk [OR = 0.84 (95% CI, 0.74–0.94; P = 0.004) per-SD increase in HDL-C], and this trend remained consistent across all sensitivity analyses17.

Circulating HDL are composed of sub particles that vary in size (5–12 nm) and composition (density 1.063–1.210 g/mL). The most abundant proteins in circulating HDL are apolipoprotein AI (60%) and AII (20%), while phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin are major phospholipids18,19. Additionally, HDL particles carry enzymes with antioxidant capacity such as paraoxonase-1 (PON1) and lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT)18. HDL protective effect resembles what has been described in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in general population20,21.

Recently, the importance of HDL has been recognized not only in terms of quantity but also in terms of its composition and functionality. In non-pregnant populations, an inverse correlation has been observed between HDL size and different systemic markers of inflammation (Gly-A, Gly-B, Gly-F), and cardiovascular death in patients with heart failure22. Also, higher levels of small HDL have been associated with 4.5-fold higher risk of diabetes mellitus in women (HR 4.56 95% CI 3.50–5.93)23.

During normal pregnancy, HDL has little to no change in concentration but increases in size, at expense of triglyceride content especially. Also, larger HDL is also associated with an increase in APO AII function, which could inhibit hepatic lipase activity to maintain lipid homeostasis24. Besides reverse lipid transport, HDL also plays a role in cholesterol efflux, hemostasis, immunity, inflammation, maintenance of endothelial function and vasodilation25.

Regarding the role of fatty acids, a recent MR analysis found that MUFA% were causally related to an increased risk of preeclampsia (OR 1.150, 95% CI 1.006–1.315, p = 0.041), while PUFA% and PUFA/MUFA were associated with decreased risk (OR 0.805, 95% CI 0.658–0.986, p = 0.036; OR 0.807, 95% CI 0.694–0.938, p = 0.005, respectively)26. For altered VLDL metabolism, changes in VLDL-triglycerides and VLDL-cholesterol have been reported in women with preeclampsia and preeclampsia with fetal growth restriction, increasing by 1.5–1.6 times and up to 2.8 times, respectively27.

Finally, women with early-onset preeclampsia showed elevated levels of short-chain amino acids. Youssef et al.28 also found an overrepresentation in the pathways of amino acid metabolism (arginine, alanine, aspartate, glutamate), in addition to alterations in lipid profile (linoleic acid) in women with early-onset preeclampsia. BCAAs are implicated in cell signaling processes and the biosynthesis of proteins. An in vitro study demonstrated that BCAA deprivation in decidua cells suppressed insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 1 (IGFBP1) production, negatively influencing the migration of human extravillous trophoblast cells29. This finding may be of particular interest for pathophysiology of preeclampsia in first trimester.

The pro- and anti-atherogenic effects of components of the lipid profile have been well-established for several decades in the general population30. However, despite previous reports in the literature, sufficient strategies have not been established to understand the effect of changes in the functionality of low molecular weight lipid particles in pregnant women. The findings of this study are consistent with other reports, both in the general population and pregnant women, regarding the protective effect of HDL and the increased risk of adverse outcomes from elevated levels of fatty acids. Moreover, the identified metabolomic profiles may help differentiate subtypes of preeclampsia and provide a better understanding of disease pathogenesis. Further longitudinal research is needed to establish whether the changes found in this study occur from the first trimester onwards and whether they additionally have a potential causal effect that could fully elucidate the mechanisms involved in populations of mixed ethnic origin and determine the therapeutic potential of HDL in this context.

Strengths and limitations

This study has some limitations. Due to the evaluation of metabolites at the time of outcome occurrence, it is not possible to establish a cause-effect relationship between the markers of interest and preeclampsia from this study. Also, cases and controls were not matched by any variable at recruitment. However, the recruitment team made significant efforts to select controls immediately after recruiting the cases, from the same hospital, and with similar age and ethnicity to the cases. Additionally, potential confounders, such as age, city of recruitment, and ethnicity, among others, were considered during the multivariate logistic regression analysis.

The study also has several strengths, including a larger sample size compared to most metabolomic studies in pregnant women assessing the risk of preeclampsia, and the detailed clinical phenotyping, including HELLP syndrome. Additionally, the Colombian population is highly admixed and is diverse compared to other published studies. This work expands the metabolic profiling data available across populations in pregnancy. Finally, the selected metabolomic platform has a wide range of clinically important metabolites been previously validated in pregnant population, and a wide range of clinically important metabolites.

Conclusions

In this observational study of Colombian pregnant women at the time of delivery, high levels of very large and large HDL metabolites associated were inversely with all preeclampsia, early-onset preeclampsia (< 34 weeks of gestation), and HELLP syndrome after adjustment for possible confounders. In addition, VLDL related metabolites were associated with an increased the risk for all preeclampsia and early-onset preeclampsia. These findings align with existing literature suggesting an important role for lipids in preeclampsia pathophysiology. Further research, including cohort studies evaluating HDL metabolite disruptions in the first trimester, could shed light on their potential predictive value for preeclampsia risk. Exploring the causal relationship between HDL and preeclampsia, as well as its severity, through Mendelian randomization studies, may also provide valuable insights. Continued exploration of lipid profiles in pregnant women can enhance the evidence base for improving risk prediction, as well as for formulating targeted medications aimed at preventing preeclampsia.

Material and methods

Design and population

A case–control study was conducted using serum samples from GenPE study (Genetics and Preeclampsia) and biobank. Briefly, GenPE is a multi-center case–control study that recruited primigravid women aged < 26 years old at the time of delivery who were free of preexisting chronic, metabolic, or autoimmune disease at childbirth between 2000 and 2012 from eight cities in Colombia. After signing informed consent, participants underwent a semi-structured interview, and peripheral blood was collected for use in preeclampsia-related studies with written patient authorization. Blood samples were collected at recruitment (during delivery) from antecubital vein using tubes devoid of anticoagulants (Becton Dickinson, USA). Following clot formation, samples underwent centrifugation for 10 min. The resulting serum was then aliquoted into 300 uL fractions and preserved at − 80 °C until the metabolomics analysis was conducted31.

Definition of preeclampsia

Preeclampsia cases were diagnosed in women who had new-onset arterial hypertension (blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg in two separate measurements) and proteinuria (≥ 300 mg in 24 h or ≥ 1 + dipstick reading in a random urine sample with no evidence of urinary tract infection) after the 20th week of pregnancy. Additional sub-phenotypes of preeclampsia were defined according to time of disease onset (early < 34 + 0 weeks, intermediate 34 weeks to 36 + 6 weeks, late ≥ 37 + 0 weeks) and severity (HELLP syndrome: hemolysis (schistocytes or total bilirubin > 1.2 mg/dL); elevated liver enzymes: AST ≥ 70 IU/L, LDH ≥ 600 IU/L; thrombocytopenia < 100,000 platelets/mm3).

Controls were normotensive women without proteinuria who delivered at term (≥ 37 weeks).

Metabolomic assessment

Metabolomic assessment was performed on serum samples using Proton Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR +) metabolomics (Nightingale Health Ltd)32 and included the measurement of 250 biomarkers (169 directly measured and 81 ratios derived from direct measurements) across eleven categories: amino acids, cholesterol, fatty acids, apolipoproteins, lipoprotein particle concentration and size, lipoprotein subclasses, glycolysis-related metabolites, glycerides and phospholipids, inflammation, ketone bodies, and fluid balance (see Supplementary material, Table S1, for a detailed list).

Quality control revealed two biomarkers (pyruvate and glycerol) with missing data in over 15% of samples, and 44 biomarkers with missing values ranging from 0.2 to 7.2% of samples (Supplementary material—Table S2). The remaining metabolites were quantified in all serum samples.

Covariates

Clinical information including age, city of recruitment, race, socioeconomic status ranging from 0 (most deprived) to 6 (most affluent) and low socioeconomic status (defined as below 3), family history (mother or sister) of preeclampsia, attendance to prenatal care, consumption of folic acid and B complex vitamins, presence of infections (vaginitis and urinary tract infections), and smoking habits during the current pregnancy was collected using a standard questionnaire. Additionally, data regarding the patients’ weight at the beginning and end of pregnancy, gestational age at delivery, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, mode of delivery and time of sampling were also recorded for all participants.

Power calculation

The power calculation was performed using Pearson’s chi-squared test (Epidat 4.2)33, based on specific assumptions. These included a proportion of exposed cases (P1) of 52.7%, a proportion of exposed controls (P2) of 65%, and a 1:1 case-to-control ratio. The difference of 13% in exposure between cases and controls was used as the basis for the calculation10. With a total sample size of 596 patients and a confidence level of 95%, this calculation demonstrated that an odds ratio (OR) of 0.6 could be detected with 80% power. Serum samples were chosen using randomized sampling, stratified by city and case/control status to ensure representativeness between the women recruited for the GenPE study and the sample for this study (Table S3).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as medians and Interquartile Range (IQR), while categorical variables are reported as absolute and relative frequencies. Missing data for each variable is also documented. Differences between cases and controls were assessed using the Χ2 statistic or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, as appropriate. For continuous variables, Wilcoxon test was employed based on their distribution. The normality of quantitative variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Metabolomic biomarkers with missing data, which corresponded to values below the limit of detection, were imputed using half the minimum value, as this was deemed appropriate, and then standardized using inverse normal transformation before association analysis.

To identify the metabolomic profile associated with preeclampsia and its subtypes, two approaches were followed. The first approach was a Metabolome Wide Association Study (MWAS) to estimate the associations between each metabolite (n = 250) and the outcomes of interest. A logistic regression model was used to assess the association between each metabolite and preeclampsia. To evaluate the association between each metabolite and HELLP syndrome, patients were classified into three groups: controls, cases without HELLP, and cases with HELLP, based on clinical and laboratory criteria. Similarly, to assess the time of onset, patients were categorized into controls, cases with late onset (≥ 37 weeks), intermediate onset (34–36.6 weeks), and early onset (< 34 weeks). In both scenarios, multinomial regression analyses were performed to account for the nature of the outcomes. Associations analyses were adjusted for age, recruitment city, race, smoking, initial and final weight, gestational age, mode of delivery and time of sampling. Variables were selected based on clinical relevance and p-value (< 0.05). The effect measure is reported as odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence interval (CI), and p-value. Given that multiple comparisons were performed, p-value was adjusted using False Discovery Rate (FDR)34. Biomarkers with an FDR-adjusted p-value < 0.0002 were considered statistically significant. For this approach, we estimated all directly quantified metabolites and their ratios.

The second approach was addressed through Weighted Gene (Metabolite) Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA)35, which included the following steps: network construction, module detection (clusters of highly interconnected metabolites), and module relationships study. For network construction, an adjacency matrix was estimated using a power (soft threshold) of 20, a correlation of 0.7 (Supplemental material—Fig. S1) based on Pearson’s method, with a minimum of 5 metabolites per module. Correlation coefficients (β) and P-values without adjustment are reported for every module detected. Finally, adjusted logistic regression coefficients were estimated to assess the associations between each module and outcomes of interest and are reported as adjusted OR (aOR). For WGCNA, only directly quantified metabolites (n = 169) were included.

The analysis was conducted in Stata v15.036 and R 3.4 (package WGCNA)35.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data are located in controlled access data storage (GitLab) at Fundación Cardiovascular de Colombia.

References

Lawrence, E. R., Klein, T. J. & Beyuo, T. K. Maternal mortality in low and middle-income countries. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 49(4), 713–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.OGC.2022.07.001 (2022).

Ngene, N. C. & Moodley, J. Preventing maternal morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia and eclampsia particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 94, 102473. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BPOBGYN.2024.102473 (2024).

Townsend, R. et al. Prediction of pre-eclampsia: Review of reviews. Ultrasound in Obstet. Gynecol. 54, 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.20117 (2019).

Sibai, B., Dekker, G. & Kupferminc, M. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet 365(9461), 785–799. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17987-2 (2005).

Rana, S., Lemoine, E., Granger, J. & Karumanchi, S. A. Preeclampsia. Circ. Res. 124(7), 1094–1112. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313276 (2019).

Lyall, F., Robson, S. C. & Bulmer, J. N. Spiral artery remodeling and trophoblast invasion in preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction: Relationship to clinical outcome. Hypertension 62(6), 1046–1054 (2013).

Jung, E. et al. The etiology of preeclampsia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 226(2S), S844–S866. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AJOG.2021.11.1356 (2022).

Dimitriadis, E. et al. Pre-eclampsia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 9(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-023-00417-6 (2023).

Mayrink, J. et al. Prediction of pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders using metabolomics: A systematic review. BMJ Open 12(4), e054697. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJOPEN-2021-054697 (2022).

Serrano, N. C. et al. Lipid profile, plasma apolipoproteins, and pre-eclampsia risk in the GenPE case-control study. Atherosclerosis 276, 189–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ATHEROSCLEROSIS.2018.05.051 (2018).

Shahid, R., Bari, M. F. & Hussain, M. Serum biomarkers for the prediction and diagnosis of preeclampsia: A meta-analysis. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 17(1), 14–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JTUMED.2021.07.003 (2022).

Spracklen, C. N., Smith, C. J., Saftlas, A. F., Robinson, J. G. & Ryckman, K. K. Maternal hyperlipidemia and the risk of preeclampsia: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 180(4), 346. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJE/KWU145 (2014).

Alonso-Ventura, V. et al. Effects of preeclampsia and eclampsia on maternal metabolic and biochemical outcomes in later life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Metab. Clin. Exp. 102, 154012. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.METABOL.2019.154012 (2020).

Stadler, J. T., Scharnagl, H., Wadsack, C. & Marsche, G. Preeclampsia affects lipid metabolism and HDL function in mothers and their offspring. Antioxidants 12(4), 795. https://doi.org/10.3390/ANTIOX12040795 (2023).

Einbinder, Y. et al. High-density lipoproteins (HDL) composition and function in preeclampsia. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 298(2), 405–413. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00404-018-4824-3 (2018).

Antonić, T. et al. Cholesterol metabolic profiling of HDL in women with late-onset preeclampsia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(14), 11357. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJMS241411357/S1 (2023).

Hosier, H., Lipkind, H. S., Rasheed, H., DeWan, A. T. & Rogne, T. Dyslipidemia and risk of preeclampsia: A multiancestry mendelian randomization study. Hypertension 80(5), 1067–1076. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.122.20426 (2023).

Rizzo M, Otvos J, Nikolic D, Montalto G, Toth PP, Banach M. Subfractions and subpopulations of HDL: An update.

Endo, Y., Fujita, M. & Ikewaki, K. HDL functions-current status and future perspectives. Biomolecules 13(1), 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/BIOM13010105 (2023).

Jung, E., Kong, S. Y., Ro, Y. S., Ryu, H. H. & Do, S. S. Serum cholesterol levels and risk of cardiovascular death: A systematic review and a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(14), 8272. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH19148272 (2022).

Cooney, M. T. et al. HDL cholesterol protects against cardiovascular disease in both genders, at all ages and at all levels of risk. Atherosclerosis 206(2), 611–616. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ATHEROSCLEROSIS.2009.02.041 (2009).

Teis, A. et al. Particle size and cholesterol content of circulating HDL correlate with cardiovascular death in chronic heart failure. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 3141. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-021-82861-6 (2021).

Mora, S. et al. Lipoprotein particle size and concentration by nuclear magnetic resonance and incident type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes 59(5), 1153–1160. https://doi.org/10.2337/DB09-1114 (2010).

Melchior, J. T. et al. Pregnancy is accompanied by larger high density lipoprotein particles and compositionally distinct subspecies. J. Lipid Res. 62, 100107. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JLR.2021.100107 (2021).

Woollett, L. A., Catov, J. M. & Jones, H. N. Roles of maternal HDL during pregnancy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 1867(3), 159106. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BBALIP.2021.159106 (2022).

Wang, Y., Liu, S., Wu, C., Yu, H. & Ji, X. Association between circulating unsaturated fatty acid and preeclampsia: A two-sample Mendelian randomization study. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. Off. J. Eur. Assoc. Perinat. Med. Fed Asia Ocean. Perinat. Soc. Int. Soc. Perinat. Obstet. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2023.2294691 (2024).

Youssef, L. et al. Paired maternal and fetal metabolomics reveal a differential fingerprint in preeclampsia versus fetal growth restriction. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 14422. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-021-93936-9 (2021).

Youssef, L. et al. The interplay between pathophysiological pathways in early-onset severe preeclampsia unveiled by metabolomics. Life (Basel, Switzerland). 12(1), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/LIFE12010086 (2022).

Tanaka, K. et al. Branched-chain amino acids regulate insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 1 (IGFBP1) production by decidua and influence trophoblast migration through IGFBP1. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 22(8), 590–599. https://doi.org/10.1093/MOLEHR/GAW032 (2016).

Nicholls, S. J. & Nelson, A. J. HDL and cardiovascular disease. Pathology 51(2), 142–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PATHOL.2018.10.017 (2019).

Colmenares-Mejia, C. C. et al. Uric acid and risk of pre-eclampsia: Results from a large case–control study and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-29651-4 (2023).

The Preventative Health Company|Nightingale Health. https://nightingalehealth.com/. Accessed 9th February 2024.

EPIDAT—Consellería de Sanidade—Servizo Galego de Saúde. https://www.sergas.es/Saude-publica/EPIDAT?idioma=es. Accessed 10th November 2022.

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Series B (Methodological) 57(1), 289–300. https://doi.org/10.2307/2346101 (1995).

Langfelder, P. & Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-9-559 (2008).

Stata: Software for Statistics and Data Science|Stata. https://www.stata.com/ [Accessed 1st February 2022].

Funding

This project was funded by Minciencias—Colombia, call 844-2019, ID 404-2020 656684468096 (CR, CCCM) and NIH-NHLBI grants, K08 HL146963 (KJG) and R01 HL163234 (KJG, JH). The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CC Colmenares-Mejia: Protocol/project development, Data collection or management, Formal analysis, Manuscript writing/editing PK. Bautista-Niño: Data and sample collection or management; Supervision; Manuscript writing/editing DC Quintero-Lesmes: Manuscript writing/editing C Riaño: Manuscript writing/editing; Funding acquisition JM Satizabal: Supervision; Manuscript writing/editing J Hu: Validation; Supervision; Manuscript writing/editing KJ. Gray: Validation; Supervision; Manuscript writing/editing NC. Serrano: Protocol/project development, Data collection or management, Data analysis; Funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

KJG has served as a consultant for BillionToOne, Aetion, Janssen Global, and Roche outside the scope of the submitted work. Remain authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Ethics approval

This study was conducted according to the international Declaration of Helsinki and Resolution 8430 of the Colombian national regulations. Ethics approval was granted by Research Ethics Committee at Fundación Cardiovascular de Colombia (May 27th, 2019. CEI 2019–00099).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Colmenares-Mejia, C.C., Bautista-Nino, P.K., Quintero-Lesmes, D.C. et al. Metabolomic profile associated with preeclampsia and its severity: a case-control study in Colombian pregnant women. Sci Rep 15, 31615 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00154-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00154-8