Abstract

We theoretically investigate the strain-tuned moiré flat bands and two-photon absorption (TPA) in magic-angle (MA) twisted bilayer graphene (TBG). Using a low-energy continuum model for strained TBG and second-order perturbation theory, we demonstrate that uniaxial strain significantly modulates both electronic and optical properties. Strain magnitude controls the flat band separation, while strain direction induces periodic variations in the band structure. The TPA spectra reveal strain-dependent features: intraband transitions dominate at higher strains, enhancing the absorption coefficient by an order of magnitude, while interband transitions exhibit characteristic spectral shifts. Notably, smaller strain direction angles yield larger TPA coefficients with red-shifted peaks. These results provide fundamental insights for developing strain-tunable optoelectronic devices based on moiré materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The emergence of “twistronics” has opened new avenues for exploring novel quantum phenomena in two-dimensional (2D) materials. By stacking two monolayer crystals with a small twist angle θ, a moiré pattern with an extended periodicity emerges, giving rise to extraordinary physical properties such as superconductivity, topological flat bands, and even-order nonlinear optical effects1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. Particularly, inTBG at the magic angle θ ≈ 1.05°, strong interlayer hybridization leads to the formation of flat bands with a high density of states, which underpin unconventional superconductivity and other intriguing phenomena10,11,12.

Beyond twist engineering, strain has emerged as an alternative and experimentally feasible approach to manipulate moiré patterns and engineer flat bands12,13,14. For instance, in TBG with a twist angle of θ ≈ 1.25°, a small uniaxial heterostrain of 0.35% is sufficient to induce flat bands13,14. Furthermore, a 0.5% uniaxial heterostrain can separate the moiré conduction and valence bands, creating a bandgap of ~ 30 meV, as commonly observed in scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) experiments13,15,16. Notably, nearly flat moiré bands have also been observed near the top of the valence band in heterostrained bilayer transition metal dichalcogenides, even in the absence of twisting13. These findings highlight the potential of strain engineering as a powerful tool for tailoring the electronic properties of 2D materials.

The ability to control electronic properties through twist and strain engineering naturally extends to the optical domain, particularly in nonlinear optical processes. The susceptibility tensor of second harmonic generation in TBG, for example, exhibits remarkable tunability ranging from 0 to 28 × 104 pm2/V depending on the twist angle17. More importantly, theoretical simulations based on the continuum model have revealed that strain systematically shifts the van Hove singularity-associated peaks in TBG’s optical conductivity18, suggesting a promising avenue for controlling light-matter interactions.

Among various nonlinear optical phenomena, TPA stands out as a particularly promising process in TBG systems. TPA offers several unique advantages for optoelectronic applications, including longer excitation wavelengths, deeper penetration depth, and higher spatial resolution19,20. These characteristics, combined with TBG’s exceptional tunability, make it an ideal platform for exploring strain-engineered TPA effects. While our previous work established the theoretical framework for twist-angle-dependent TPA in unstrained graphene systems21, the incorporation of strain engineering remains unexplored despite its demonstrated capability to tailor electronic properties in 2D moiré systems. This knowledge gap motivates our current investigation into strain-modulated TPA properties in TBG, aiming to unlock new possibilities for advanced optoelectronic applications.

Theoretical framework

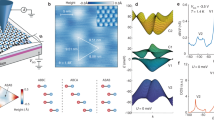

We begin by examining AA-stacked bilayer graphene and introduce a deformation through two distinct modifications: (1) a relative twist between the layers by − θ/2 and + θ/2 respectively, and (2) application of uniaxial strains of equal magnitude but opposite directions to layers 1 and 2. Figure 1 illustrates the resulting moiré pattern for TBG with relative twist angle θ, along with its corresponding Brillouin zone.

(a) Top view of the moiré pattern of TBG. The small blue and black dots represent the atoms in layers 1 and 2, respectively. (b) Primitive cell basis vectors of untwisted bilayer graphene and the uniaxial strain application directions of angle \(\phi\) with respect to the axis x. (c) Schematic illustration of moiré BZ for TBG. The two large blue and red regular hexagons represent the BZ of layers 1 and 2, respectively. And the small black regular edges shape the moiré BZ of TBG. (d) The moiré BZ of TBG with strain for ξ = − 1 valley.

The twisting deformation modifies the Brillouin zones of both layers, while the applied strain transforms the regular hexagonal Brillouin zone into a flattened hexagonal configuration (Fig. 1(d)). In the small-angle approximation, the total deformation tensor ε, which incorporates both the strain tensor S(s, \(\phi\)) and rotation matrix R(θ), can be expressed as13:

Since both the strain and twist to the two layers are of the same magnitude and opposite directions, the total deformation tensor of the two layers has the relationship ε2 = − ε1 = ε/2. The uniaxial strain which is dependent on the magnitude s and direction \(\phi\) is written in a 2 × 2 matrix as13

The Poisson ratio for graphene is taken as ν = 1.6. The primitive lattice vectors of pristine monolayer graphene are defined as a1 = a(1, 0) and a2 = a(1/2, \(\sqrt 3\)/2), where a ≈ 0.246 nm is the graphene lattice constant. The corresponding reciprocal lattice vectors are given by b1 = 2π/a (1, –1/\(\sqrt 3\)), b2 = 2 π/a (0, 2/\(\sqrt 3\)). The first Brillouin zone (BZ) of each layer forms a regular hexagon, with Dirac points located at \({\text{K}}_{0\xi } = - \xi \frac{4\pi }{{3a}}(1,0)\), where ξ = ± 1 indexes the two valleys. After applying the deformation caused by twisting combined with strain, a moiré pattern is formed and the shape of both the unit cell and the BZ are changed. The primitive lattice vectors and the reciprocal lattice vectors of the moiré superlattice are transformed by \({\text{a}}_{i}^{{M}} = \varepsilon^{ - 1} {\text{a}}_{i}\) and \({\text{b}}_{i}^{{M}} = \varepsilon^{\text{T}} {\text{b}}_{i}\) with i = 1, 2. Since the lattice construction problem in TBG with strain has been presented in detail in Refs.12,13 and references therein, we won’t go into this again. This geometrical deformation produces a moiré superlattice whose BZ is no longer a regular hexagon but a stressed one (Fig. 1(c)). Under the two center approximation and the small strain limit, the coordinate position of Dirac fermions in momentum space can be given by Mannaï12 and Bi et al.13:

where \({\text{G}} = \frac{\sqrt 3 }{{2a}}\beta (s_{xx} - s_{yy} , - 2s_{xy} )\) is the effective gauge connection for the low energy Dirac fermions with the hopping modulus factor β ≈ 310. I is the Identity matrix. We can derive the coordinates of the two Dirac points in valley associated with the parameters s, \(\phi\) and θ as following:

At small twist angles, the period of the moiré pattern is much longer than the lattice constant, resulting in negligible interactions between different energy valleys. Regarding the interlayer tunneling, the Hamiltonian of TBG system can be written under the low-energy continuous model as12

where

are the Hamiltonians of layer 1 and 2 written in the vicinity of \({\text{K}}_{1\xi }\) with the vector \({\mathbf{q}}_{j\xi }\)(j = 1, 2, 3) which connects the Dirac point \({\text{K}}_{1\xi }\) and three Dirac points \({\text{K}}_{2\xi ,j}\) around \({\text{K}}_{1\xi }\) by \({\mathbf{q}}_{1\xi } = {\text{K}}_{1\xi } - {\text{K}}_{2\xi }\), \({\mathbf{q}}_{2\xi } = {\mathbf{q}}_{1\xi } + \xi {\text{b}}_{1}^{{M}}\), and \({\mathbf{q}}_{3\xi } = {\mathbf{q}}_{1\xi } + \xi ({\text{b}}_{{M}} + {\text{b}}_{2}^{{M}} )\). Once the basic structural unit composed of \({\text{K}}_{1\xi }\) and the nearest three Dirac points \({\text{K}}_{2\xi ,j}\) is determined, the reciprocal lattice space of TBG with strain is fixed. The matrices Tj are the interlayer tunneling which is reduced to \(T_{1} = w({\mathbf{I}} + {\varvec{\sigma}}_{x} )\),\(T_{2} = w({\mathbf{I}} - \frac{1}{2}{\varvec{\sigma}}_{x} + \xi \frac{\sqrt 3 }{2}{\varvec{\sigma}}_{y} )\) and \(T_{3} = w({\mathbf{I}} - \frac{1}{2}{\varvec{\sigma}}_{x} - \xi \frac{\sqrt 3 }{2}{\varvec{\sigma}}_{y} )\), with Pauli matrice σ and the interlayer tunneling amplitude w ~ 118 meV whenever the bilayer graphene is AA or AB stacking12,13. By diagonalizing the Hamiltonian in Eq. (4), we obtain the low-energy band structure of strained TBG. Using the eigenvalues and wave functions derived from the continuum model, we calculate the TPA coefficient α2 for strained TBG through second-order perturbation theory of photon-electron interactions22:

TPA coefficient α2 is related with the transition rate W2 by Eq. (8), where \(\hbar \omega\) the incident photon energy, d the thickness of TBG and I the intensity of the incident light. Mfi is the transition matrix element when electron absorbs two photons and then transits from initial state φi to final state φf through an intermediate state φm. Ei, Ef, Em are the corresponding energy levels of these three states. Hint is the electron-photon interaction Hamiltonian which is expressed as Hint = e \(\hbar\)/(mec)A·k with electron charge e, effective mass me, speed of light in vacuum c and the light wave vector potential A.

Numerical results and discussion

This section systematically investigates how the positions of Dirac points, electronic band structures, and TPA spectra evolve with both twist angle and applied strain. Our analysis focuses on twist angles near the magic angle (θ ≈ 1.1°), where correlated electronic states are most prominent. For the strain range, we select 0.1% to 0.6% uniaxial strain based on two key considerations. For one thing, this range aligns with experimentally achievable strain levels in TBG samples as reported in Ref.23; for another thing, it represents a physically meaningful regime where strain effects become observable while maintaining sample integrity—higher strains (> 0.6%) could induce defects or layer decoupling, while smaller strains (< 0.1%) would produce negligible modifications to the electronic structure.

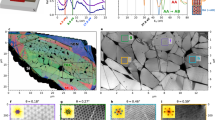

Figure 2 demonstrates the cooperative effects of strain and twist angle on moiré BZ deformation and Dirac point dynamics in TBG. For uniaxial strain with \(\phi\) = 0°), K1 and K2 exhibit transverse kₓ displacements, whose magnitude depends on both strain amplitude s and direction \(\phi\), as governed by the trigonometric relations in Eqs. (4)–(5). Notably, a critical angle \(\phi\) = π/6 separates two distinct regimes: below π/6, trajectory slope increases with \(\phi\), while above π/6 it decreases (Fig. 2b). Figure 2(c)–(d) shows the twist-angle dependence of Dirac point positions at fixed strain (s = 0.3%, \(\phi\) = 0 − π/3), revealing exclusive ky shifts described by \({\mathbf{K}}_{\xi } (y) \propto \pm \frac{2\pi \theta }{{3a}}\xi\), where ± corresponds to K1, K2 in ξ valley. Remarkably, the observed degeneracy for \(\phi\) = 30° (40°)/60° (50°) stems from sin2 \(\phi\) symmetry. These results establish orthogonal control of Dirac points via strain and twist, with enhanced effects compared to monolayer systems24,25, consistent with theoretical predictions26.

Trajectory movement of two Dirac points K1, K2 in the first BZ for the ξ = − 1 valley under twisting and uniaxial strain in bilayer graphene. k was measured with respect to the unstrained and untwisted Dirac point which was marked with “ + ” in figure. (a)–(b) Dirac points shift with the uniaxial strain when twist angle is fixed as θ = 1.05°. (c)–(d)The Dirac points shift with the strain direction and twist angle under strain magnitude s = 0.3%.

The band structure of TBG is effectively modulated by both twist angle and strain. For θ = 1.05°, flat bands with a bandwidth of ~ 9 meV emerge near the Fermi level at the Γ point in the absence of strain (Fig. 3a). Applying uniaxial strain preserves the flat bands while systematically increasing the band gaps (Fig. 3(b)–(d)). Strain direction further tunes the band structure. At s = 0.6%, the flat band gaps exhibit non-monotonic dependence on \(\phi\). For K1, the gap peaks at 36 meV (\(\phi\) = 10°) before decreasing sharply to 6 meV (\(\phi\) = 40°), while at M1 it reaches 46 meV (\(\phi\) = 10°–20°) then slightly decreases to 42 meV (\(\phi\) = 40°) (Fig. 4). This demonstrates that strain magnitude and direction provide independent control over band topology, consistent with Refs.12,13. The retention and tunability of these flat bands under strain offer promising avenues for engineering correlated states in moiré systems.

The strain-dependent evolution of flat band gaps in TBG reveals profound symmetry-selective modulation, as evidenced by the three-dimensional plots of gaps at high-symmetry points K and M (Fig. 5). At the K point, the band gap exhibits clear π/3 periodicity in strain direction \(\phi\), with the first maximum occurring at \(\phi\) ≈ 15°. This tripled periodicity reflects the underlying threefold rotational symmetry C3 of the Dirac cone. In striking contrast, the M point displays a fundamentally different π-periodic response, featuring a primary maximum at \(\phi\) ≈ 10° and a secondary peak at \(\phi\) ≈ 80° within the first cycle. This doubled periodicity emerges from the lower symmetry of the Brillouin zone boundary, where the electronic states couple differently to strain perturbations13. The observed harmonic modulation at M point, characterized by distinct primary and secondary maxima, suggests a more complex strain coupling mechanism compared to the K point. Beyond directional effects, the band gaps at both symmetry points show monotonic enhancement with increasing strain magnitude at fixed angles, consistent with the band structure evolution shown in Figs. 3, 4. Notably, while monolayer graphene requires substantial strain to directly open a bandgap27,28,29, TBG demonstrates much richer strain response—preserving flat bands while continuously modulating their separation. This distinct behavior stems from the moiré-induced renormalization of the strain coupling in TBG, which breaks the simple degeneracy of flat bands while maintaining their overall character26. We also display the energy gap between the two flat bands vary with twist angle and strain magnitude at \(\phi\) = 15°in Fig. 5(c)–(d). It is found that the variation of bandgap is more significantly regulated by the magnitude of strain magnitude than twist angle. The quantitative mapping of these strain-gap relationships provides crucial insights for designing strain-tunable quantum phases in moiré systems.

The TPA process in TBG involves electronic transitions through intermediate states, which can be categorized into intra-conduction band, intra-valence band, and interband transitions based on the involved band structure (Fig. 3(d))30. Our analysis reveals that strain-mediated modification of flat bands profoundly influences these optical transitions, as demonstrated by the TPA spectra near the M point for θ = 1.05° (Fig. 6(a)). The spectrum exhibits four distinct peaks in the mid- to far-infrared range, with a characteristic “dimple” feature emerging near 50 meV photon energy. This distinctive spectral feature originates from the energy gap asymmetry between conduction and valence bands near the M point, where the low-energy peaks (< 50 meV) are dominated by intraband transitions (Fig. 6(c)–(d)), while the high-energy peaks (> 50 meV) primarily arise from interband transitions (Fig. 6(b)), creating measurable deviations between their transition resonances.

Two-photon absorption spectra associated with the nearest six energy bands near zero energy in twist bilayer graphene with twist angle θ = 1.05° and different strain magnitude at strain direction \(\phi\) = 15°. (a) Both the interband and intraband transitions are involved; (b) Interband transition two-photon absorption spectra; (c) Intra-conduction band transition two-photon absorption spectra; (d) Intra-valence band transition two-photon absorption spectra.

Systematic investigation of strain effects shows that increasing strain magnitude from 0.3 to 0.6% dramatically enhances the TPA coefficients, with intraband transitions becoming dominant at higher strains (10 times stronger than interband transitions at 0.6% strain). Notably, the interband transition peaks at 70 meV and 95 meV exhibit a “seesaw” behavior with varying strain. Furthermore, when examining strain direction effects at fixed magnitude (Fig. 7), we observe that as the strain direction approaches the normal to the material surface, the TPA coefficients increase significantly while the absorption peaks undergo a systematic red-shift. These comprehensive results demonstrate that strain engineering provides powerful control over TPA pathways through its modification of flat band topology, with the transition-type-dependent responses offering new possibilities for developing graphene-based nonlinear optical devices with tunable properties.

Conclusion

In this study, we have systematically investigated the strain- and twist angle-dependent electronic and optical properties of TBG using a low-energy continuum model. Our theoretical analysis reveals that uniaxial strain induces characteristic displacements of Dirac points in the moiré Brillouin zone, with distinct periodic modulations of the flat band gap observed at high-symmetry points—showing π/3 periodicity at the K point and π periodicity at the M point, particularly significant near the magic angle. These findings demonstrate the profound influence of strain direction on the electronic structure of TBG. Through second-order perturbation theory of electron-photon interactions, we have further elucidated the strain-dependent nonlinear optical response of TBG. The calculated two-photon absorption (TPA) spectrum exhibits four distinct peaks in the mid- to far-infrared regime, with their relative intensities and positions strongly dependent on both strain magnitude and direction. Notably, we observe that intraband transitions become increasingly dominant at higher strains (0.6%), exhibiting a remarkable tenfold enhancement in the TPA coefficient compared to interband transitions. The interband transition peaks, meanwhile, display a characteristic “seesaw” behavior with increasing strain. The TPA coefficient shows particularly strong directional dependence, increasing significantly as the strain direction approaches the sample normal while simultaneously undergoing a systematic red-shift. Our results demonstrate strain engineering as an effective approach to control TBG’s electronic and optical properties. The tunable TPA effects, including enhanced intraband transitions and direction-dependent spectral shifts, enable novel optoelectronic devices. Future work should explore combining strain with electric fields or doping for multi-parameter control of moiré materials.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Andrei, E. & MacDonald, A. H. Graphene bilayers with a twist. Nat. Mater. 19, 1265–1275 (2020).

Balents, L. General continuum model for twisted bilayer graphene and arbitrary smooth deformations. SciPost Phys. 7, 048 (2019).

Naik, M. H. & Jain, M. Ultraflatbands and shear solitons in moiré patterns of twisted bilayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 266401 (2018).

Naik, M. H., Kundu, S., Maity, I. & Jain, M. Origin and evolution of ultraflat bands in twisted bilayer transition metal dichalcogenides: Realization of triangular quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 102, 075413 (2020).

Nimbalkar, A. & Kim, H. Opportunities and challenges in twisted bilayer graphene: A review. Nano-Micro Lett. 12, 1–20 (2020).

Suárez Morell, E., Correa, J. D., Vargas, P., Pacheco, M. & Barticevic, Z. Flat bands in slightly twisted bilayer graphene: Tight-binding calculations. Phys. Rev. B 82, 121407 (2010).

Tarnopolsky, G., Kruchkov, A. J. & Vishwanath, A. Origin of magic angles in twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 106405 (2019).

Wu, F., Lovorn, T., Tutuc, E., Martin, I. & MacDonald, A. H. Topological insulators in twisted transition metal dichalcogenide homobilayers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 086402 (2019).

Zhu, Z., Carr, S., Massatt, D., Luskin, M. & Kaxiras, E. Twisted trilayer graphene: A precisely tunable platform for correlated electrons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 116404 (2020).

Cao, Y. et al. Correlated insulator behaviour at half-filling in magic-angle graphene superlattices. Nature 556, 80–84 (2018).

Cao, Y. et al. Unconventional superconductivity in magic-angle graphene superlattices. Nature 556, 43–50 (2018).

Mannaï, M. & Haddad, S. Phys. Rev. B 103, L201112 (2021).

Bi, Z., Yuan, N. F. & Fu, L. Designing flat bands by strain. Phys. Rev. B 100, 035448 (2019).

Huder, L. et al. Electronic spectrum of twisted graphene layers under heterostrain. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 156405 (2018).

Choi, Y. et al. Electronic correlations in twisted bilayer graphene near the magic angle. Nat. Phys. 15, 1174–1180 (2019).

Kerelsky, A. et al. Magic angle spectroscopy. arxiv:1812. 08776 (2018).

Yang, F. et al. Tunable second harmonic generation in twisted bilayer graphene. Matter 3, 1361–1376 (2020).

Cai, X. X., Luo, G. Y., Li, Z. Q. & He, Y. Optical conductivity of twisted bilayer graphene under heterostrain. Acta Phys. Sin. 70, 187301 (2021).

Luo, X., Feng, X., Liu, Y. & Guo, J. Rashba spin-orbit coupling enhanced two-photon absorption and its polarization dependence in monolayer black phosphorus. Opt. Express 28, 9089–9098 (2020).

Zhang, S. et al. Direct observation of degenerate two-photon absorption and its saturation in WS2 and MoS2 monolayer and few-layer films. ACS Nano 9, 7142–7150 (2015).

Zhou, C., Feng, X. & Gong, R. Angle-tunable two-photon absorption in twisted graphene systems. Physica E 140, 115204 (2022).

Nathan, V., Guenther, A. H. & Mitra, S. S. Review of multiphoton absorption in crystalline solids. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B-Opt. Phys. 2, 294–316 (1985).

Kerelsky, A. et al. Maximized electron interactions at the magic angle in twisted bilayer graphene. Nature 572, 95–100 (2019).

Li, C. L. New position of Dirac points in the strained graphene reciprocal lattice. AIP Adv. 4, 087119 (2014).

Li, Z., Liu, Z. & Liu, Z. Movement of Dirac points and band gaps in graphyne under rotating strain. Nano Res. 10, 2005–2020 (2017).

Nguyen, V. H. & Dollfus, P. Strain-induced modulation of Dirac cones and van Hove singularities in a twisted graphene bilayer. 2D Mater. 2, 035005 (2015).

Pereira, V. M., Castro Neto, A. H. & Peres, N. M. R. Tight-binding approach to uniaxial strain in graphene. Phys. Rev. B 80, 045401 (2009).

Cocco, G., Cadelano, E. & Colombo, L. Gap opening in graphene by shear strain. Phys. Rev. B 81, 241412–241415 (2010).

Ni, Z. H. et al. Uniaxial strain on graphene: Raman spectroscopy study and band-gap opening. ACS Nano 2, 2301–2305 (2008).

Gong, R., Zhou, C. & Feng, X. Magnetic field dependent two-photon absorption properties in monolayer MoS2. Phys. Rev. B. 105, 195301 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 12264057, 12264055), the Key Applied Basic Research Program of Yunnan Province (202201AS070023), Yunnan Revitalization Talent Support Program, the Spring City Plan: The High-level Talent Promotion and Training Project of Kunming (2022SCP005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Lianmeng Yu: Methodology, Investigation, Writing—Original Draft; Zhaoming Fu: Data Curation, Software, Validation; Peizhi Yang: Writing—Review and Editing;Xiaobo Feng (Corresponding Author): Conceptualization, Funding Acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing—Review and Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, L., Fu, Z., Yang, P. et al. Strain-enhanced two-photon absorption in twisted bilayer graphene. Sci Rep 15, 15565 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00158-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00158-4