Abstract

The impending crisis for food production is the biggest threat to sustenance of soil resources due to industrial farming practices adopted by multitudes of farmers on all parts of the world inclusive of the Southern Telangana Zone (STZ) in India. This can extensively degrade the soil if not substituted by soil resource-saving agricultural systems. This present experiment is implemented to assess the impact of contrasting tillage practices and weed management practices on soil nutrient stratification ratio (SR), carbon sequestration rate (CSR), carbon management indices (CMI), carbon retention efficiency (CRE) and monitor the grain yield of maize after three-years in CA with a cotton-maize-Sesbania rostrata cropping system. Three tillage practices (main-plots) included the T1:Conventional tillage with cotton- Conventional tillage with maize- fallow i.e., No Sesbania rostrata (Farmers’ practice), T2:Conventional tillage with cotton- Zero tillage with maize- Zero tillage with Sesbania rostrata and T3: Zero tillage with cotton + Sesbania rostrata residues- Zero tillage with maize + Cotton residues- Zero tillage with Sesbania rostrata + Maize stubbles. Weed management tactics (Sub plots) were W1: Chemical weed control, W2: Herbicide rotation, W3: Integrated weed management and W4: Single hand-weeded control. Sampling of the soil in the 0 − 15 and 15–30 cm, subsequent to harvesting of maize was analyzed for pH, EC, soil macronutrient’s availability, soil organic carbon (SOC), and computed for soil nutrients SR, CSR, CMI and CRE duly following the standard analytical procedures. The results indicated that in the 0–15 cm, 15.3% of SOC, 15.1% of available soil N, 19.6% of available soil P and SR of 1.20 for SOC were higher under T3 relative to T1. Similarly, 58.1% of cumulative CSR, 58.8% of CRE in the 0–30 cm, and 30.3% of CMI in the 15–30 cm were higher under T3 compared to T1. The passive pool of carbon (CPSV) was the dominant contributor of SOC to total SOC in the 0–30 cm soil layer. The T3 had higher Kernel yield (11.6%) in comparison T1. Kernel yield was also 23.4–43.1% higher under W1, W2, W3 over W4. These findings suggest that adoption of zero tillage (ZT) with crop residue retention (T3), IWM and chemical weed control/ herbicide(s) could be a viable solution for improving the soil health and contributing towards enhanced crop productivity in cotton-maize-Sesbania rostrata cropping system in this zone.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Paris agreement states that about 195 countries agreed on a new climate treaty described as ‘a monumental triumph for people and our planet’ and to combat climate change, accelerate, and intensify the actions and investments needed for a sustainable low carbon future aimed at strengthening the global response to climate change by keeping a global temperature rise well below 2 degrees Celsius, above pre-industrial levels, and to pursue efforts of limiting the temperature increase, even further to 1.5 degrees Celsius1. India has already committed itself to restore 26 million hectares of degraded land by 2030, aimed at achieving “Land Degradation Neutrality” (LDN) which entails significant carbon sequestration via increased forest and tree cover etc., thus creating an additional carbon sink of 2.5 to 3 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent2. This initiatives are intended to respond to meet the demand for food production of 10 billion population increase across the world by 20503. Cereal-based production is predominantly followed in the Southern Telangana Zone (STZ) of India and contributes to nearly 40% of the overall cereal production of the country4. Maize is the second essential crop cultivated during the winter season following rice in STZ of India. Globally, available soil resources are declining at an alarming rate mainly due to overexploitation of these resources under commercial farming practices5, which may pose a challenge of meeting sustainable development goals (SDGs) (1) “no poverty,” (2) “zero hunger,” and 15. “life on land” coined by the United Nations. About 10 hectares of land assigned for agricultural production get depleted instantly as a result of various degradation processes such as erosion, nutrient depletion, etc6. These are the consequences of urbanization and industrial agricultural systems.

According to United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP), during the second half of the 20th century, around two billion hectares of land catered for agriculture had undergone extensive soil degradation7. India is comprised of approximately 328.8 M ha, total geographical area, of which 180 M ha falls under agricultural production with various soil kinds. It bolsters up to 17.5% of the global population with 2.4% of global geographical area and 9% of cultivable land. Approximately one hundred and twenty million hectares of cultivable land is regarded as degraded in India8 which is a considerable solicitude for sustainable food production9. Thus, an increase in productivity in an attempt to meet the shortage of food with shrinking land resources, must always be supported by a sustainable agricultural system to cease or at least slow-down the adverse effects on the quality and quantity of soil resources, land degradation and biological diversity10. In the light of this challenging context for agriculture, soil organic carbon (SOC) forms the base for sustainable soil resources being a reservoir for the overall soil available nutrients11. In spite of that, the SOC content in India is as low as 0.3 per cent from 1% in the previous 70 years which is of great concern to keep the pace in agricultural production12.

Soil nutrients are of utmost importance in plant nutrition and constitute about 95% of the food production13. The availability of these nutrients in optimum amounts in the soil are crop yields determinant factor, thus, the linkage between long-term specific soil management practices like conservation agriculture (CA) through the adoption of sustainable tillage systems and weed control strategies are necessitated in order to comprehend soil management practices which can extensively increase crop yield and enhance soil quality14. CA is defined as a notion of soil resource preservation for agricultural production, based on augmenting the activities occurring above and beneath the land naturally and biologically on a long-term basis. Lowering of tillage intensity minimizes soil disruption, covering the soil with crop residues and short-duration crops permanently and diversified rotation of crops for attaining greater production while conserving soil and water conservation effectively as well as sequestering adequate SOC align with CA precepts15. The soil environmental gains of zero tillage (ZT) with at least 30% crop residues retained in CA are well-established16,17 and the main factor behind the success of ZT coupled with other CA precepts is preservation of SOC and soil nutrients via SOC storage and nutrient’s accumulation in the soil stratum18. Several studies have reported the sur face and the spatial distribution of SOC, and various soil nutrients, but research on the quantification of their long-term storage and accumulation in the different soil profile is very limited in STZ. The stratification of soil nutrients and compositions, particularly of soil pH, EC, CEC, C, N, P have been found to be very common in various vegetation and croplands19,20. The stratification ratio (SR) is defined as the ratio of a soil attribute at the soil surface in a profile to that at a lower soil depth in a profile. The high SR values (generally > 2) denote good soil quality20.

Alterations in farming management practices comprised of conservation tillage and crop residue incorporation in CA have been observed to furnish some soil health gains on improving essential soil quality parameters (e.g. SOC, nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium etc.) with great potential to sequester SOC in STZ of India21. Bochalya et al.22. deduced that CA sequesters the greatest SOC adjacent to the upper soil layer. Thus, the contentious outcomes of the influence of tillage with regard to alterations in SOC status and storage may result in misconception of the impacts of tillage practices on soil functions. Further, factors such as variations in various soil types, climatic conditions, and cropping systems will also pose difficulty to get consistent conclusions on how tillage practices affect soil quality23. The knowledge on carbon management index (CMI) under conservation agricultural practices particularly in the semi-arid regions of STZ in India is of utmost importance for the preservation of soil resources, and minimal adverse environmental impacts. These insights on these aspects of CMI are crucial in regions where soils are intrinsically low in OC concentration and productivity is frail as in STZ. To better understand the mechanisms by which C is maintained in the soil, the total organic carbon (TOC) in soil gets split into the labile, slow pool, and passive, recalcitrant pool with changes in residence duration24. The labile pool of carbon is the portion of TOC having the most instant turnover periods. Simultaneously, this fraction is essential for crop productivity perspective as it provides the soil food systems, thus impacting nutrient cycling for preservation of soil quality and production25,26. The latest meta-data analysis indicated that the influence of conservational tillage practice in comparison with conventional tillage (CT) on crop yields, is inconsistent and impacted substantially by certain crop factors27. Traditionally, farmers control weeds in maize by pre-emergence herbicide spraying followed by inter-cultivation and manual weeding13. The introduction of new-generation selective herbicides and scarcity of manual labor to perform manual weeding has led to a significant rise in pre-emergence and post-emergence herbicide utilization in maize crops. Several studies have confirmed the adverse as well as the positive impacts of agro-chemicals on crop productivity28. However, the over-use and excess application of such herbicides tend to exude into the soil environment resulting in bio-accumulation and generation of a vast quantity of residues which in turn may lead to nutrient imbalance and quality drop-off in crop production13. Thus far, research studies on long-term storage of SOC, its management indices, and soil nutrients distribution within various soil layers in STZ of India are scarce with synergistic contrasting tillage and weed management practices in CA. Adoption of conservation tillage can sustain the soil health and quality, and improve cereal-based crop production in STZ. Thus, the current three-years CA experiment has been taken up to identify the best tillage and weed management practice that can maintain high maize production levels and improve the soil quality through quantification of stratification ratio of SOC, soil nutrients, SOC sequestration, CMI, and target yield of maize, after the third year of maize crop cycle under cotton-maize-Sesbania cropping system.

Materials and methodologies

Details and characterization of the experimental area

This current field study was undertaken at College Farm, PJTSAU, Southern Telangana Zone of India under All India Coordinated Research Project (AICRP) on Weed Management. The field trial is located at 160 18’ 17” North latitude and 780 25’ 38” East longitude presented as satellite outlook in Supplementary Fig. 1. The zone is dryland with approximately 708 mm of mean annual rainfall29. The experiment was implemented from 2019 in the monsoon, winter, and summer seasons under cotton (Gossypium hirsutum), maize (Zea mays), green manure (Sesbania rostrata) rotations, respectively. An experiment continued from 2019 until 2024 and collection of soil samples for analysis of soil parameters and yield estimation were done after harvest of winter maize crop in 2023-24 (after fifth year in the 10th crop cycle). Meteorological observations taken during the crop development from the station situated at the Institute of Agricultural Research (IAR), Rajendranagar on weekly basis are presented in Supplementary Fig. 2.

Soil characteristics

The soil of the study area falls under the soil order Inceptisol, sandy clay loam in texture, red chalk in color, slightly alkaline (7.82) in soil pH as a result of available lime concretion beneath the horizon, 1.23 Mg m-3 in bulk density, non-saline (0.33 dS m-₁), medium range in soil organic carbon (6.50 g kg-₁), low range in available soil nitrogen (220.90 kg ha-₁), medium range in available soil phosphorus (22.40 g kg-₁), and high range in available soil potassium (408.75 kg ha-₁) in the soil surface (0–15 cm) at initiation of experiment.

Design of the experiment and treatment details

Conservation agriculture (CA) experiment was conducted in accordance with a split-plot design with three tillage (s) practices in the main plots, as shown in Table 1; four weed management options in the sub-plots as detailed in Supplementary Table 1; and treatment combinations of tillage and weed management were replicated thrice. For T1, which was subjected to conventional tillage, the plots were prepared by plowing two times, followed by rotovating and seeding. In T2, no-till of the soil (Zero tillage- ZT) i.e., seeding was done directly by opening the soil followed by surface soil sealing, and in T3, there was ZT (cotton) + Sesbania rostrata residues (SrR) in monsoon – ZT (maize) + cotton residues (CR) in winter – ZT (Sesbania rostrata) + maize stubbles (MS) (i.e., Sesbania rostrata was sown adjacent to maize stubbles) in summer. The succeeding crops (cotton and Sesbania rostrata) residues were shredded and retained (as surface mulch), and seeding was performed directly by opening the soil, accompanied by surface sealing with mulch from crop residues (Table 1).

The cumulative mean annual input of organic biomass/residues from cotton and Sesbania rosrata retained in T3 plots, since the year 2019–2024, was about 200.0 to 240.0 Mg ha-₁, estimated according to30. The weed management strategies used included: W1: chemical weed control, W2: herbicide rotation, W3: integrated weed management (IWM), and W4: single hand-weeded control, as fully described in Supplementary Table 1. No-tillage operations or weed management were implemented prior to the sowing of summer Sesbania rostrata, as it was cultivated up to 45 days to be retained and cover the soil in T3. There was no Sesbania rostrata sown in the T1 plots; i.e., the plots were fallowed during the summer season.

Crop management

Sowing and fertilizer application during maize development

The experimental particulars and attributes of crop varieties are shown in supplementary Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Before sowing of the crops (cotton and maize), the field was plowed twice followed by rotovation and levelling field operators in conventionally tilled (T1) plots, whereas in no-till (ZT) plots, seeds dibbling was performed. The cotton and maize crops were thinned in the portions of the plots with high crop population and gap filled where seeds did not emerge 13 and 10 days, respectively after seed emergence. For Sesbania, sowing was done directly in solid rows (30 cm spacing) between the maize stubbles in the T2 and T3 treatments without any tillage operations. Conversely, the CT (T1) plots were fallowed during summer i.e., there was no Sesbania in such plots. This distinction in management practices reflects the specific treatments applied to each plot in the experimental design. The crops particularly cotton and maize were raised in accordance with recommended dose of fertilizers (RDFs); the N: P: K (120-60-60 kg ha− 1) were applied in the form of urea, di-ammonium phosphate (DAP) and muriate of potash (MOP) for cotton. The recommended dose of phosphorus (RDP) was applied in the form of DAP as basal after cotton emergence in T1, T2 and T3. Urea were applied at 30 DAS, flowering stage and square formation stages of cotton in equal splits; the N: P: K (200:60:50 kg ha-₁) were supplied through urea, DAP and MOP, respectively to raise maize crop. Application of urea and DAP were split thrice as basal, at knee height and maize tasseling period. No fertilizer application during growth and development of Sesbania rostrate. Both the crops (cotton and maize) were fully developed following cultural practices and typically advanced with rainfall in monsoon during cotton and supplemental irrigation in winter during maize. At 30 days after sowing (DAS), Sesbania rostrata was knock-down and removed in the T2 while in the T3, shrub master was used to shred and retain Sesbania as surface mulch to the soil. The details on the dates of sowing and harvesting for each crop are presented in supplementary Table 4.

Sampling and standard analytical procedures

Soil samples were randomly picked in triplicate and mixed thoroughly from each treatment plot at a depth of 0–15 and 15–30 cm after the harvest of maize crop (10th crop cycle) in April, 2023. These collected samples were well air-dried under shade, processed through a wooden hammer and passed through 0.5-millimeter sieving, and then analyzed for organic carbon (OC). For analysis of soil pH, electrical conductivity (EC), and soil macronutrient availability (nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K) a 2-millimeter sieve was used for sieving the soil samples. Laboratory analysis was performed by following the standard protocols suggested by Walkley and Black31 for OC, Subbiah and Asija32 for available soil N, Olsen et al.33 for available soil P, Jackson (1973) for available soil K, soil pH and electrical conductivity (EC), and Blake and Hartge34 for bulk density (BD) in the 0–15 cm and 15–30 cm soil layers. BD was computed on the basis of oven-dry weight using Eq. (1):

Where; Ms represent the mass of soil on oven-dry basis in megagram (Mg),

Vts is the summation volume of soil core in cubic meters (m−3).

Quantification of stratification ratio (SR)

The stratification ratios (SRs) of SOC, EC, pH, N, P and K were computed by20.

SOC stock, sequestration and carbon retention efficiency

The grand total for organic carbon (OC) stocks in both 0–15 cm and 15–30 cm (0–30 cm) layers was calculated using Eq. (2):

The bulk density (BD) for 0–15 cm soil layer was the overall average of the treatment means, which was 1.34 Mg m-3 was determined post-harvest of maize crop. Similarly, the BD for 15–30 cm soil depth (D) in meters (m) was 1.36 Mg m-3. The OC stocks of two layers (0–15 and 15–30 cm) were added up as to derive the entire SOC stock of the sampling profile.

Calculation for Sequestration of SOC was achieved using Eq. (3) by Srinivasarao et al.35:

Retention of carbon efficiency (CRE) was computed using Eq. (4) suggested by (Bhattacharyya et al.36. :

SOC stocks (Mg ha-₁) derived from initial and final, and CEI are estimated carbon input accrual (Mg ha-₁) calculated in order to evaluate the rates of SOC sequestration.

Soil organic carbon pools and carbon management index

Various pools of OC were computed by a modified Walkley and Black method described by Chan et al.25. Total organic carbon (TOC) was calculated using the Eq. (5) by Jha et al.37. ;

The lability index (LI) and carbon management index (CMI) were calculated as per the following Eqs. (6 and 7)38.

CPI is carbon pool index. The SOC in the reference is from undisturbed soil (collected) under the trees adjacent to the experimental field which was 12.52 g kg-1 for 0–15 cm and 8.95 g kg-₁ for 15–30 cm. While estimating SOC in the reference, composition of soil in the 0–15 and 15–30 cm soil layers were drawn from virgin soils beneath the trees adjacent to the experimental field. Sample composition was obtained by taking 3 soil samples at random depth-wise (0–15 and 15–30 cm) and intermix them and was the soil samples representative which were collected. The carbon management index was calculated by the following (Blair et al.38. formula;

Crop yield, harvest index and estimated carbon input

Maize grains produced from individual plots were air-dried under shade until 12% moisture content was achieved and weighed prior to threshing, recorded and presented in kg ha-₁. Similarly, the stover yield was cut down, air-dried, weighed and expressed in kg ha-₁. The harvest index was calculated as the percentage of maize grain yield by biological yield. The cumulative mean annual input of organic biomass/residues to the soil from all crops within the cropping system (cotton – maize – Sesbania rosrata) for the year 2020 was estimated as 52.3 to 60.0 Mg ha-₁. After three years of the cropping system, 2023 it was about 200.0 to 240.0 Mg ha-₁. Thus, about 80.0–100.0 Mg ha-₁ of biomass (C input) was added to the soil in the 0–30 cm soil layer through residues incorporation/retention under various tillage and weed management treatments. The estimated carbon input (ECI) was calculated by taking the maximum value (100.0 Mg ha-₁) of cumulative C input and multiplying it with assumed carbon content of 40%30.

Statistical and principal component analysis

The data was analyzed statistically by applying the analysis of variance technique, dully following the ANOVA for two-way analysis as described by Panse and Sukhatme39. The critical variances for testing the means for statistical significance was computed at 5 per cent probability level. Turkey’s test was used to rank the treatment means for their significance at 5% probability level. Standardized PCA was performed on the correlation matrix as proposed by Andrews et al.40 and Govaerts et al.41 in ‘R’ software42.

Results

Soil bulk density

The soil bulk density (BD) ranged from 1.30 to 1.39 and 1.28–1.44 Mg m-3 in 0–15 and 15–30 cm soil depths, respectively across all the treatments (Supplementary Table 5). Among tillage practices, CT(C)-CT(M)-Fallow (NSr) recorded significantly lower BD (1.30 Mg m-3) in 0–15 cm compared to ZT(C) + SrR-ZT(M) + CR-ZT(Sr) + MS. The higher BD (1.44 Mg m-3) was observed under CT(C)-CT(M)-Fallow (NSr) in 15–30 cm compared to ZT(C) + SrR-ZT(M) + CR-ZT(Sr) + MS (Supplementary Table 5). The BD values were higher than the initial BD value (1.23 Mg m-3).

Soil physicochemical properties

Soil organic carbon (SOC)

The adoption of different tillage practices exerted a significant impact on SOC at both soil sampling depths. The ZT(C) + SrR-ZT(M) + CR-ZT(Sr) + MS exhibited a significantly higher SOC (7.92 g kg-₁) over CT(C)-CT(M)-Fallow (NSr) and CT(C)-ZT(M)-ZT(Sr). In the 15–30 cm, SOC was reduced in all the treatments in comparison with 0–15 cm soil depth (Supplementary Table 5). The trends on SOC in 15–30 cm depth were similar to that of the 0–15 cm, based on the treatment performance. Overall, SOC contents were higher in all the treatments than their initial values (Supplementary Table 5).

Soil pH and electrical conductivity (EC)

Soil pH and EC were not significantly influenced by tillage and weed management practices, and the treatment’s interaction effects on pH and EC were non-significant (Supplementary Table 5). However, a reduction in pH was observed across all tillage practices and weed management practices over the initial pH values at both sampling depths, while EC was increased above the initial value in both soil layers. Further, pH increased with an increase in soil depth and EC decreased with an increase in soil depth (Supplementary Table 5).

Available soil nutrients

It is evident that available soil macronutrients (N, P and K) content fell below the initial value(s) under CT(C)-CT(M)-Fallow(NSr), CT(C)-ZT(M)-ZT(Sr) and all weed management practices (Supplementary Table 6). The ZT(C) + SrR-ZT(M) + CR-ZT(Sr) + MS significantly enhanced the available soil N, and P over the initial values (Supplementary Table 6). A drastic decrease of the overall soil macronutrients availability was observed when soil depth was increased (15–30 cm).

Stratification ratios (SRs) of soil physico- chemical properties and available nutrients

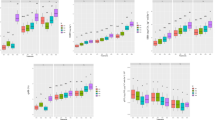

The SRs of soil physico-chemical characteristics (SOC, pH and EC) and soil macronutrients (available N, P, K) are depicted in Figs. 1a, b and c and 2a, b and c, respectively. The SRs ranged from 0.96 to 0.97 for pH, 1.14–1.19 for EC, 1.10–1.21 for SOC (Fig. 1a, b, c) and 1.26–1.38 for available soil N, 1.17–1.22 for available soil P and 1.07–1.23 for available soil K (Fig. 2a, b, c). Among tillage practices, the significantly higher SR for SOC (1.21) was recorded under ZT(C) + SrR-ZT(M) + CR-ZT(Sr) + MS. Similar results were observed for SRs of N, P, K in which the ZT(C) + SrR-ZT(M) + CR-ZT(Sr) + MS recorded significantly higher SR compared to other tillage systems examined (Fig. 2a, b, c). However, SR values obtained were less than (< 2.0). Hence, these results have indicated that soil parameters viz., SOC and N, P, K availability have the capability to improve SRs under the adoption of ZT(C) + SrR-ZT(M) + CR-ZT(Sr) + MS practice.

(a–c) Effect of tillage practices and weed management options on stratification ratio of soil physico-chemical properties (soil pH, electrical conductivity (EC) and soil organic carbon (SOC). Means having distinct symbols demonstrate significant variances between the treatments at 5% probability level (Tukey’s test) and means having the same symbols indicate no significant variances among the treatment means at 5% probability level. Refer to Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1 for treatment details.

(a–c) Effect of tillage practices and weed management options on stratification ratio of available soil nutrients (N, P, K). Means having distinct symbols demonstrate significant variances between the treatments at 5% probability level (Tukey’s test) and means having the same symbols indicate no significant variances among the treatment means at 5% probability level. Refer to Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1 for treatment details.

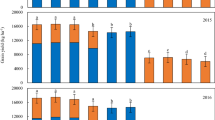

Soil organic carbon (SOC) stocks, SOC sequestration rate (CSR) and carbon retention efficiency (CRE)

The SOC stocks and SOC sequestration rate varied with increase in soil depths and were significantly influenced by tillage at soil surface (0–15 cm). Weed management practices did not show any significant difference (Table 2). In the 0–15 cm depth, the SOC stocks was significantly superior (15.92 Mg ha-₁) under ZT(C) + SrR-ZT(M) + CR-ZT(Sr) + MS compared to CT(C)-CT(C)-Fallow (NSr) (13.60 Mg ha-₁) and CT(C)-ZT(M)-ZT(Sr) (14.59 Mg ha-₁). The ZT(C) + SrR-ZT(M) + CR-ZT(Sr) + MS has restored SOC stocks at 0–15 cm depth, while it was spread over in the soil, particularly in the ploughed profile in CT systems. The treatment interaction effects on SOC stock were non-significant. The cumulative (0–30 cm soil depth) carbon stocks and rates of C sequestration followed the same pattern as SOC stocks and SOC sequestration rate in both the soil layers (0–15 cm and 15–30 cm) (Table 2). The greatest cumulative SOC stocks (29.18 Mg ha-₁) and C-sequestration rate (1.98 Mg C ha-₁ yr-₁) were recorded under ZT(C) + SrR-ZT(M) + CR-ZT(Sr) + MS compared to the CT(C)-CT(C)-Fallow(NSr) and CT(C)-ZT(M)-ZT(Sr) (Table 2). The carbon retention efficiency (CRE) was significantly highest (11.90%) under ZT + R(C)-ZT + R(M)-ZT + R(Sr) and higher (8.40%) under CT(C)-ZT(M)-ZT(Sr) compared to CT(C)-CT(C)-Fallow(NSr). CRE was significantly influenced by weed management, and tillage and weed management interaction effects were not significant (Fig. 3). The linear relationship of CRE and C-sequestration rate to cumulative C stocks as indicated by the regression analysis graphs was significant (P = 0.05) (Fig. 4a and b).

Effect of tillage practices and weed management options on carbon retention efficiency (CRE). Means having distinct symbols demonstrate significant variances between the treatments at 5% probability level (Tukey’s test) and means having the same symbols indicate no significant variances among the treatment means at 5% probability level. Refer to Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1 for treatment details.

Soil organic carbon (SOC) pools and total organic carbon (TOC)

SOC pools and TOC were positively impacted by tillage practices in the 0 − 15 and 15–30 cm soil layers. The very labile carbon: CVL (3.35 g kg-₁), less labile carbon: CL (2.68 g kg-₁), less labile carbon: CLL (2.42 g kg-₁), and TOC (11.69 g kg-₁) were significantly higher under ZT(C) + SrR-ZT(M) + CR-ZT(Sr) + MS (Table 3). The SOC pools followed the order; CVL> CL> CNL> CLL, across all tillage and weed management treatments at both soil sampling depths. In the 15–30 cm, the trend was found to be similar to 0–15 cm soil layer for CVL, CL and TOC, but the decrease compared to 0–15 cm depth. The CNL and CLL fluctuated inconsistently and were not significantly influenced by the treatments and their interactions (Table 3).

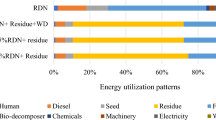

Passive and active pools of oxidizable soil organic carbon

The passive (CPSV) and active (CACT) pools of carbon were significantly impacted by different tillage systems and weed management choices in the 0–30 cm soil layers (Figs. 5a and b). Three tillage practices indicated that 46–49% of CACT and 51–54% of CPSV pools were contributed to TOC, in the 0–30 cm (Fig. 5a). Similarly, 45–52% of CACT and 48–55% of CPSV pools were contributed to TOC by four weed management options (Fig. 5b).

The ratio of CACT to CPSV pools ranged from 0.90 to 1.50 and 0.60–1.80 in the 0–15 and 15–30 cm soil layers, respectively (Fig. 6). This ratio of CACT to CPSV pools was found to be greater than 1.0 across all the treatment combinations except under CT(C)-ZT(M)-ZT(M) in combination with herbicide rotation (T2W2) and ZT(C) + SrR-ZT(M) + CR-ZT(Sr) + MS on interaction with herbicide rotation (T3W2) in the 0–15 cm soil layer. The treatment combinations; CT(C)-CT(M)-Fallow(NSr) and chemical weed control (T1W1), CT(C)-CT(M)-Fallow(NSr) and single hand-weeded control (T1W4), ZT(C) + SrR-ZT(M) + CR-ZT(Sr) + MS and single hand-weeded control (T3W4) recorded higher CACT: CPSV pool of 1.50 in the 0–15 cm relative to all other treatment combinations. In the 15–30 cm soil layer, significantly higher CACT: CPSV pool of 1.80, 1.70 and 1.50 was noticed under ZT + R(C)-ZT + R(M)-ZT + R(Sr) on interaction with IWM (T3W3), ZT + R(C)-ZT + R(M)-ZT + R(Sr) in combination with herbicide rotation (T3W2), CT(C)-ZT(M)-ZT(M) in combination with single hand-weeded control (T2W4), respectively relative to all other tillage and weed management combinations (Fig. 6).

Carbon lability, pool, and management index

LI and CPI were significantly influenced by tillage practices in 0–15 and 15–30 cm soil layers. (Table 4). The ZT(C) + SrR-ZT(M) + CR-ZT(Sr) + MS was observed with significantly higher LI (2.26), CPI (0.63) and CMI (142.47) in the 0–15 cm (Table 4). The trend observed in the 0–15 cm, was similar for 15–30 soil layer, in which ZT(C) + SrR-ZT(M) + CR-ZT(Sr) + MS was found to be significantly higher on LI, CPI and CMI. Interestingly, depth-wise comparison of CMI had indicated that a significantly higher CMI (146.32) was recorded under ZT(C) + SrR-ZT(M) + CR-ZT(Sr) + MS, followed by CMI of 121.50 under CT(C)-ZT(M)-ZT(Sr) in the 15–30 cm compared to 0–15 cm soil layer, indicating better soil management with increase in soil depth from 15 to 30 cm (Table 4).

Crop yield and harvest index

Tillage and weed management practices exerted a significant influence on maize grain yield (kernel yield). There was no significant effect (P = 0.05) observed on harvest index (HI) by tillage practices and weed management options subsequent to harvest of maize (Table 5). A significantly higher KY (6801 kg ha− 1) was recorded under ZT(C) + SrR-ZT(M) + CR-ZT(Sr) + MS, while significantly lower KY (6014 kg ha− 1) was observed with CT(C)-CT(M)-Fallow(NSr). Adoption of chemical weed control and herbicide rotation resulted in significantly higher KY (7245 kg ha− 1 and 7324 kg ha− 1), followed by integrated weed management (IWM) with KY of 6722 kg ha− 1. The significantly lower KY (4099 kg ha− 1) was exhibited by single hand-weeded control (Table 5).

Discussions

The soil management practices which involve(s) tillage, and diversified cropping system in conservation agriculture (CA) may alter the bulk density (BD) and soil organic carbon (SOC). The decrease in the intensity of tillage and continuous maintenance of crop remains under CA are essential tactics for the preservation of soil resources and sustenance of agro-ecosystems with limited mechanical practices and judicious use of chemical inputs43. Soil play a key role as a source or sink for carbon, depending on advanced agricultural management techniques, and also contributes significantly in carbon cycling44. These interface implementations can modify nutrient pathways and availability to the crop, slow-down rates of evaporation, and decomposition of SOM and, consequently improve carbon repository capacity45. In this present investigation, lower BD values were observed in the top soil layer under conventionally tilled (CT) plots probably due to intensive tillage operations. In contrast to that, the BD exhibited an increasing trend in the upper soil layer for zero tilled plots which might be the result of low soil disturbance. Similar findings were reported by Abaganduru et al.46. who have observed that the BD in the top soil, from 0 to 20 cm was higher for Zero tillage (ZT), accompanied by minimum tillage (MT), which demonstrated that lowering of tillage intensity slow-down soil disturbance, thus, leading to a rise in BD in the top soil. The increase in the depth of the soil profile demonstrated an increase in BD particularly under CT practices and could be attributed to heavy farm machinery load and continuous removal of crop residues having a negative impact on soil compaction. These results are supported by Hobbs and Gupta47. Similarly, Alabi et al.48. have reported that sub-surface soils encounter low soil disturbance relative to surface soils, which result in an increased BD.

Less BD exhibited by conservation tillage i.e., ZT(C) + SrR-ZT(M) + CR-ZT(Sr) + MS in the 15–30 cm could be associated with continuous retention of cotton and Sesbania crop residues on fixed plots, and enhanced SOC content. The impact of weed control strategies on BD and SOC remain unknown and this is consistent with the findings of Anshuman et al.49. who observed non-significant influence on BD and SOC by four hand-weeding and integrated weed control.

In the present investigation, soil organic carbon (SOC), stocks and nutrient availability such as soil available nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) are favored by reduced tillage with cumulative retention of the crop residues in CA practices, proven by the results of the present experiment. These findings are in congruence with the discovery of Sapre et al.50. in which the increments on soil N and P availability where Sesbania rostrate and maize residues were retained in rice, rice residues in wheat and wheat residues in maize in a four-years CA experiment, and SOC stocks51 in the eastern Himalaya zone with the adoption conservation tillage. This could be due to regular build-up of crop residues, which augmented the soil system with N and P from decomposed SOM. Significantly higher N availability was also announced by Alam et al.52. in the upper soil surface under ZT in wheat-mungbean cropping sequence. Cotton and maize crops are predominant and exhaustive in nature4 and absorb vast amounts of available soil nutrients particularly in CT systems which removes the crop leftovers subsequent to harvest. This could be the result for soil nutrient availability to fall below the initial values. These results concur with that of Sapre et al.50. who observed a non-remarkable variation of N, P, K under CT managed system relative to the initial soil nutrient availability status. The SOC stocks, pools and total organic carbon (TOC) were significantly reduced when soil sampling depth increased ascribed to soil surface residue accrual and less concentration of the roots in the soil sub-surface. These research findings concur with that of Yadav et al.53. , Choudhary et al.54. and Kumar et al.55. However, non-labile (NLL) pool of SOC was observed to be significantly higher under CT(C)-CT(M)-Fallow(NSr) in the 15–30 cm in comparison with 0–15 cm soil depth probably due to its recalcitrant.

The gains for sequestering SOC as to sustain the soil resources and crop production through adoption of a suitable tillage practice are well-established and documented56,57. The carbon retention efficiency (CRE) is a measure of how well an ecosystem and soil microbes function together to retain carbon in the soil. Carbon sequestration rate (CSR) is a mechanism in which carbon is being captured and stored from the atmosphere into the soil on long-term basis. In the current study, the greatest cumulative CSR, CRE, TOC was observed under ZT(C) + SrR-ZT(M) + CR-ZT(Sr) + MS which could be attributed to no-disruption of the soil aggregates and high SOM content brought about by added crop residues and permanent soil cover under diverse cropping system, indicating more rapid turn-over for active C (CACT) pool and tillage as a determinant factor over CRE and SOC sequestration rate. Yadav et al.53. also reported the beneficial effects of no-till with the addition of crop residues and adequate C-inputs on enhancing C-reserves and transposing the process of soil degradation over conventional tilled systems. The distribution of SOC pools were lower under conventional tillage plots probably due to intensive ploughing and removal of the plant residues after crop harvest. Similar results were discovered by Khambalkar et al.58. , and Chivane and Battacharyya59 in which the distribution of SOC pools were very less in the CT tillage systems in the absence of crop residues probably due to less biomass production. In contrast to that, several studies have reported a reduction in the tillage intensity along-with the addition of crop residues to have resulted in the build-up of very labile and labile carbon under CA scenarios60,61 and modification of SOC lability and its indices viz., lability index (LI), carbon pool index (CPI) and carbon management index (CMI), consequently influencing the soil quality62, which agrees with the results of the present investigation. Lability index (LI) was significantly higher in the 0–15 cm under ZT(C) + SrR-ZT(M) + CR-ZT(Sr) + MS ascribed to a greater amount of CL pool in such treatment. LI has been elucidated by Hazra et al.63. as the sum of of the corresponding weightage of CL pool, thus a greater LI signifies productive soil with the highest CACT. The CPI was used to show the accrual of carbon (C) with respect to the reference C (C was drawn from virgin soils in the trees adjacent to the study area). Parihar et al.64. had indicated that the greater CPI signifies the accrual of SOC in the soil relative to the lower CPI. It is well-known that SOC under the trees particularly from virgin soils is more than that of the cultivable lands. It is also well-established and documented that agricultural management practices such as CA, can bolster the CPI under diversified cropping systems. Conservation tillage i.e., ZT(C) + SrR-ZT(M) + CR-ZT(Sr) + MS adopted in the current experiment had recorded a higher CPI particularly in the 15–30 cm possibly due to inclusion of Sesbania rostrata well-known to have a rapid decomposition rate due to less lignin content and low C: N ratio leading to more C input, which revealed more accrual of SOC for the entire soil profile (0–30 cm). Similar research findings were reported by Yadav et al.53.

No-till and or reduced tillage (RT) under intensive cropping systems is broadly deemed as a viable alternative for enhancing CMI under various agro-ecological systems38. The CMI is acquired from TOC pool, and is essential for assessing the magnitude of agricultural systems adopted for promoting soil quality and enhancing SOC sequestration38,62,65. The higher CMI value (s) signifies the best agricultural management practices significant to elevate SOC and bolster the soil quality66. In the present study, the adoption of tillage practices and weed management options in the 0–15 and 15–30 cm soil depths have positively influenced CMI. The higher CMI values were observed in the15-30 cm than 0–15 cm soil depth with significantly higher values observed under by ZT(C) + SrR- ZT(M) + CR-ZT(Sr) + MS which could be interlinked with appropriate adoption of tillage and weed management combinations, C inputs and less soil disruption.

The ZT(C) + SrR-ZT(M) + CR-ZT(Sr) + MS when combined with single hand-weeded control resulted in significantly higher CACT: CPSV in the 15–30 cm soil layer, and was the dominant contributor of CACT pool to TOC for the entire soil sampling profile depth (0–30 cm) which could probably be due to less soil disturbance, crop residue addition in conjuction with cultural weed control, well-known to harbor a vast diverse group of microbes for decomposition of the crop residues. The CACT: CPSV was more than 1 in the ZT(C) + SrR-ZT(M) + CR-ZT(Sr) + MS in combination with all weed management practices in the 15–30 cm soil layer, signifying more easily labile or oxidizable fractions than recalcitrant form of carbon. In contrast, Kumar et al.55. reported CACT: CPSV ratio of less than 1 under CT and weed management combinations, indicating more of recalcitrant carbon than easily oxidizable pools.

The stratification ratio (SR) is a great measure of soil quality, and values of SR are normally higher at deeper soil profile. The SR becomes significant where a huge variation between the soil surface and sub-surface exist. In the present study, the SRs were found to be equal to or greater than 1 in the overall treatments. However, the significantly higher SRs were notable under the ZT(C) + SrR-ZT(M) + CR-ZT(Sr) + MS which could be due to less soil disturbance and high SOM content resultant to addition of continuous crop residues. These results concur with Franzlueebbuers20 who had reported the variation for SR of SOC as 1.1–1.9 in the 0–15: 12.5–20 cm soil sampling depth under CT and 2.1–3.4 under ZT induced by continuous build-up of soil surface C input, although the sampling depth was different from the present investigation. Similarly, Sapre et al.50. announced the overall significant rise on SR for SOC and total nitrogen (TN) in the deeper soil depths under all the tillage treatments with greatest (2.24) being observed under ZT followed by reduced tillage (RT) with 1.62 and CT with 1.42. However, there is no consistent figure for SR which has been reported to signify a high soil quality67. Among all soil attributes studied, SOC and available soil N were found to have higher SRs indicating that the soil quality can be assessed better through SRs of SOC and soil N availability.

Better growth/development of crops and increased yield rely to a large extent on tillage practices, as these play a crucial role in determining the development of the crop’s rooting system, the soil volume explored by the roots for moisture and nutrients, the availability of air, and the regulation of soil temperature, among other factors. The importance of crop-weed interaction in determining the competition faced by the crop plants for the light, moisture and space is well-established. Confined root growth lead to decreased nutrient uptake and poor crop growth. The meta-data analysis of ZT with residue retention indicated that the effect on crop yields in comparison with CT, is inconsistent and impacted substantially by cropping systems followed by aridity index, crop residue maintenance, ZT duration, and weed management strategies27. In this present investigation, maize grain, and harvest index demonstrated higher values when subjected to the ZT(C) + SrR-ZT(M) + CR-ZT(Sr) + MS treatment in comparison to other tillage methods. This superior performance can be interconnected to the development of robust, deep-rooted systems in the crops facilitated by the practice of zero tillage.

The implementation of ZT is thought to augment the nutrient absorption capacity of the crops, thereby fostering their physiological growth and overall development. Furthermore, the preservation of crop residues on the soil surface under the ZT(C) + SrR-ZT(M) + CR-ZT(Sr) + MS treatment likely contributed to the enhanced retention and availability of soil moisture. This aspect proves especially crucial during the post-tasseling stage of the maize crop, which coincided with a hot period from mid-March to May. Given the limited moisture conditions during this period, supplemental irrigation was applied to ensure optimal soil moisture levels throughout the crop development. The research outcomes by You et al.68. also indicated that short-term reduced tillage (rotary-till and no-till) and residue incorporation enhanced soil properties and spring maize grain yield, growth and attributes and increased root biomass and shoot ratio. Furthermore, the interaction of tillage and residue treatments can increase crop biomass and yield69,70. Several previous studies conducted on short-term conservation tillage have not paid full attention as to how yield can be improved.

No-till enhances root biomass, shoot biomass, regulate shoot to root ratio, and increase yield in comparison with plow-till and rotary-till71,72. Residue incorporation can also enhance crop biomass and yield due to enhanced soil buffer capacity73,74. The post-emergence tank-mix combination of atrazine and tembotrione herbicide was applied at recommended rates in both W1 and W2 which resulted in effective weed control and no phyto-toxicity. The absence of phytotoxic effects suggests the efficacy and safety of the tembotrione and atrazine combination in weed management, contributing to better crop performance. Poor crop performance was also observed under unweeded control which ultimately reflected in yield. This could be due to high weed density at critical crop growth stage which out competed with the crop for available moisture, nutrient, light and rooting space. Ganapathi et al.75. also recorded higher kernel, harvest index, and least weed dry weight with IWM compared to the use of only advocated herbicides and non-weeded treatments due to less weed infestation. Similar results were obtained by Kumar et al.55. who observed that when pre-emergence herbicide was applied followed by one rotary hoeing at 35 DAS led to increased grain and stover yield. The results of Ahmad et al.76. concur with the findings of this present investigation, who noticed that Nicosulfuron application and one-hand weeding with a hoe at 15 DAS led to greater kernel yield, whereas the least kernel yield was obtained from unweeded control. In the current study, there was an increase in corn yield and HI when employing a zero tillage with crop residue retention (ZT + R) and chemical weed control and IWM. This improvement could be attributed to the synergistic effects of efficient weed management achieved through the use of both chemical and cultural mechanical control tactics, along with the moisture and nutrient preservation facilitated by no-till practices that retained crop residues. These results are supported by Ahmad et al.76. who deduced that maize can flourish when cultivated in zero tillage either with application of atrazine, glyphosate or with hand weeding (HW) at 40 DAS alternative to manual weeding in spring seasons to attain higher grain yield.

Conclusions

A Conservation agricultural experiment was undertaken to examine its impact on soil quality parameters (SQPs) and yield of maize. The results indicated that zero tillage (ZT) with crop residues retention to the soil enhanced the SOC, available soil nutrient status and stratification ratio (SR), cumulative Carbon sequestration rate (CSR), carbon retention efficiency (CRE), active carbon (CACT), and passive carbon(CPSV) pools in the order; very labile carbon (CVL) > labile carbon (CL) > non-labile carbon (CNL) > less labile carbon (CLL), kernel yield (KY) and CACT to CPSV pool ratio in the sub-surface soil layer (15–30 cm). CPSV pool was the dominant contributor of soil organic carbon (SOC) to total organic carbon (TOC). The kernel yield (KY) was observed to be significantly higher under chemical weed control and integrated weed management (IWM). Based on the results of the present investigation, it may be deduced that the impact of tillage practices and weed management options offers a decisive insight on evaluating both tillage and weed management practices that would better enhance the soil health status indicated by the contents of SOC and improve yieldof maize in cotton- maize- Sesbania rostrata cropping system in the region of Southern Telangana in India. No-till with crop residues retention and IWM alternative to chemical weed control could be recommended treatment combination to the farmers to increase productivity of maize and alleviate the possible soil degradation process in this region. However, these treatments thereof may not be suitable agricultural management practices for certain regions depending on the certain factors such as the agronomic management practices, climate variability and soil types etc. To gauge the SQPs up to the depth of 30 cm only may also not give a clear pathway and idea on the levels of SOC. This suggest that future research on CA experiments should be conducted to further monitor the crop yield response and soil quality on long-term basis, considering the soil depth beyond 30 cm as to authenticate these SQPs on implemented agricultural management practices in Southern Telangana region.

Data availability

Available upon request and the corresponding author should be contacted on request.

References

COP 21. ‘UN chief hails new climate change agreement as monumental triumph’ UN News. https://news.un.org/en/story/2015/12/517982-cop21-un-chief-hails-new-climate-change-agreementmonumental-triumph (2015).

UNCCD. www.unccd.int/news-stories/press-releases/world-leaders-call-global-action-restore-degraded-land (2019).

Gunawardena, M. A., Lokupitiya, E. & Gunawardena, P. Land degradation neutrality and carbon neutrality: approaches, synergies, and challenges. Front. Forests Global Change. 7, 1398864 (2024).

Nthebere, K., Sharma, S. H. K., Kumari, C. P. & Qureshi, A. A. Long-term effect of different cropping systems on carbon sequestration in a sandy loam soil of Telangana. Agricultural Reviews. 43 (2), 249–254 (2022).

Foley, J. A. et al. Solutions for a cultivated planet. Nature 478 (7369), 337–342 (2011).

UNCCD. Land and soil in the context of a green economy for sustainable development, food security and poverty eradication, the Submission of the UNCCD Secretariat to the Preparatory Process for the Rio + 20 Conference. Revised Version 18 (2011).

Oldeman, L. R., Hakkeling, R. T. A. & Sombroek, W. G. World Map of the Status of human-induced Soil Degradation: an Explanatory Note. (International Soil Reference and Information Centre, 1990).

Maji, A. K., Obi Reddy, G. P. & Sarkar, D. Degraded and Wastelands of India—Status and Spatial Distribution. (A Joint Publication of ICAR and NAAS, 2010).

Nthebere, K. et al. Impact of conservation agricultural practices on Depth-wise distribution of soil Physico-chemical attributes and available soil nutrients under Cotton-Maize-Sesbania cropping system. Biological Forum –. Int. J. 15 (8a), 496–502 (2023a).

Weiss, M., Jacob, F. & Duveiller, G. Remote sensing for agricultural applications: A meta-review. Remote Sens. Environ. 236, 111402 (2020).

DeBano, L. F. & Wood, M. K. Soil loss tolerance as related to rangeland productivity. In Proceedings of Soil Quality Standards Symposium. 15–27 (1990).

National Rainfed Area Authority. Ministry of Agriculture and Farmer’s Welfare. (Government of India, 2022).

Nthebere, K. et al. Changes in Soil Physical Properties and Available Micronutrients as Influenced by Tillage and Weed Management Strategies under Diversified Cropping System. Biological Forum – An International Journal, 2023.15(9), 131–140. (2023).

Zulu, S. G., Magwaza, L. S., Motsa, N. M., Sithole, N. J. & Ncama, K. Long-Term No-Till conservation agriculture and nitrogen fertilization on soil micronutrients in a Semi-Arid region of South Africa. Agronomy 12 (6), 1411 (2022).

FAO. Conservation agriculture. Rome. https://www.fao.org/3/i4009e/i4009e (2022).

Hobbs, P. R., Sayre, K. & Gupta, R. The role of conservation agriculture in sustainable agriculture. Philosophical Trans. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 363 (1491), 543–555 (2008).

Thierfelder, C. & Wall, P. C. Investigating conservation agriculture (CA) systems in Zambia and Zimbabwe to mitigate future effects of climate change. J. Crop Improv. 24 (2), 113–121 (2010).

Verhulst, N. et al. Conservation agriculture, improving soil quality for sustainable production systems. Adv. Soil. Science: Food Secur. Soil. Qual. 1799267585, 137–208 (2010).

Chang, R., Fu, B., Liu, G., Wang, S. & Yao, X. The effects of afforestation on soil organic and inorganic carbon: A case study of the loess plateau of China. Catena 95, 145–152 (2012).

Franzluebbers, A. J. Soil organic matter stratification ratio as an indicator of soil quality. Soil. Tillage Res. 66 (2), 95–106 (2002).

Parihar, C. M. et al. Long term effect of conservation agriculture in maize rotations on total organic carbon, physical and biological properties of a sandy loam soil in north-western Indo-Gangetic plains. Soil Tillage. Res. 161, 116–128 (2016).

Bochalya, R. S. et al. Conservation agriculture: an option to mitigate the adverse effect of climate change: A review. Pharma Innov. J. 10 (7), 51–65 (2021).

Zhao, X. et al. Stratification and storage of soil organic carbon and nitrogen as affected by tillage practices in the North China plain. PLoS One 10(6), e0128873. (2015).

Parton, W. J. & Rasmussen, P. E. Long-term effects of crop management in wheat‐fallow: II. CENTURY model simulations. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 58 (2), 530–536 (1994).

Chan, K. Y., Bowman, A. & Oates, A. Oxidizible organic carbon fractions and soil quality changes in an oxic paleustalf under different pasture leys. Soil Sci. 166 (1), 61–67 (2001).

Majumder, B., Mandal, B., Bandyopadhyay, P. K. & Chaudhury, J. Soil organic carbon pools and productivity relationships for a 34-year old rice–wheat–jute agroecosystem under different fertilizer treatments. Plant. Soil. 297, 53–67 (2007).

Pittelkow, C. M. et al. When does no-till yield more? A global meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 183, 156–168 (2015).

Dhanker, R., Goyal, S., Kumar, K. & Hussain, T. Bacterial community response to pesticides polluted soil. In Recent Advancement in Microbial Biotechnology, 339–355. (Academic, 2021).

Kadiyala, M. D. M. et al. Assessment of climate change and vulnerability in Indian state of Telangana for better agricultural planning. Theoret. Appl. Climatol. 143, 309–325 (2021).

Bolinder, M. A., Janzen, H. H., Gregorich, E. G., Angers, D. A. & VandenBygaart, A. J. An approach for estimating net primary productivity and annual carbon inputs to soil for common agricultural crops in Canada. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 118 (1–4), 29–42 (2007).

Walkley, A. & Black, I. A. An examination of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter, and a proposed modification of the chromic acid Titration method. Soil Sci. 37 (1), 29–38 (1934).

Subbiah, B. V. & Asija, G. L. A rapid procedure for the Estimation of available nitrogen in soils. Curr. Sci. 25 (8), 259–260 (1956).

Olsen, S. R. Estimation of Available Phosphorus in Soils by Extraction with Sodium Bicarbonate. No. 939 (US Department of Agriculture, 1954).

Blake, G. R., Hartge, K. H. & Bulk density. Methods of soil analysis: Part 1. Physical and mineralogical methods 5, 363–375. (1986).

Srinivasarao, C. et al. Soil carbon sequestration and agronomic productivity of an Alfisol for a groundnut-based system in a semiarid environment in Southern India. Eur. J. Agron. 43, 40–48 (2012).

Bhattacharyya, R. et al. Effect of fertilization on carbon sequestration in soybean–wheat rotation under two contrasting soils and management practices in the Indian Himalayas. Soil. Res. 47 (6), 592–601 (2009).

Jha, P. et al. Predicting total organic carbon content of soils from Walkley and black analysis. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 45 (6), 713–725 (2014).

Blair, G. J., Lefroy, R. D. & Lisle, L. Soil carbon fractions based on their degree of oxidation, and the development of a carbon management index for agricultural system. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 46, 1459–1466 (1995).

Panse, V. G. & Sukhatme, P. V. Statistical Methods for Agricultural Works. (ICAR, 1978).

Andrews, S. S., Karlen, D. L. & Mitchell, J. P. A comparison of soil quality indexing methods for vegetable production systems in Northern California. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 90 (1), 25–45 (2002).

Govaerts, B., Sayre, K. D. & Deckers, J. A minimum data set for soil quality assessment of wheat and maize cropping in the highlands of Mexico. Soil Tillage. Res. 87 (2), 163–174 (2006).

Team, R. D. C. R. A language and environment for statistical computing. (2010).

Liu, X. et al. Zoning of rural water conservation in China: A case study at Ashihe river basin. Int. Soil. Water Conserv. Res. 3 (2), 130–140 (2015).

Blakemore, R. J. Non-flat Earth recalibrated for terrain and topsoil. Soil. Syst. 2 (4), 64 (2018).

Iqbal, M., Ul-Hassan, A. & van Es, H. M. Influence of residue management and tillage systems on carbon sequestration and nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium dynamics of soil and plant and wheat production in semi-arid region. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 42 (5), 528–547 (2011).

Abagandura, G. O., Nasr, G. E. D. M. & Moumen, N. M. Influence of tillage practices on soil physical properties and growth and yield of maize in Jabal al Akhdar, Libya. Open. J. Soil. Sci. 7 (7), 118–132 (2017).

Hobbs, P. R. & Gupta, R. K. Sustainable resource management in intensively cultivated irrigated rice–wheat cropping systems of the Indo-Gangetic Plains of South Asia: Strategies and options. In: International Conference on Managing Natural Resources for Sustainable Production in 21st Century 14–18. (2000).

Alabi, A. A. et al. Effects of different land uses on soil physical and chemical properties in Odeda LGA, Ogun State, Nigeria. Environ. Earth Sci. 78, 1–14 (2019).

Anshuman, K., Singh, R. R., Yadav, S., Singh, N. & Kumar, N. Studies on the effect of weed management practices on soil parameters and availability of N, P, and K under turmeric (Curcuma longa L). Pharma Innov. 10 (4), 596–599 (2021).

Sapre, N., Singh, P., Kewat, M. L. & Sharma, A. R. Cumulative effect of tillage and weed management practices on soil property, weed dynamics and productivity of Mungbean (Vigna radiata L.) in rice-wheat-mungbean cropping system. J. Pharmacognosy Phytochemistry. 8 (1), 1881–1886 (2019).

Das, A. et al. Tillage and cropping sequence effect on physico-chemical and biological properties of soil in Eastern Himalayas, India. Soil Tillage. Res. 180, 182–193 (2018).

Alam, M. K., Islam, M. M., Salahin, N. & Hasanuzzaman, M. Effect of tillage practices on soil properties and crop productivity in wheat-mungbean-rice cropping system under subtropical Climatic conditions. Sci. World J. 20, 2–9 (2014).

Yadav, G. S. et al. Potential of conservation tillage and altered land configuration to improve soil properties, carbon sequestration and productivity of maize based cropping system in Eastern Himalayas, India. Int. Soil. Water Conserv. Res. 9 (2), 279–290 (2021).

Choudhary, V. K., Kumar, P. S. & Bhagawati, R. Response of tillage and in situ moisture conservation on alteration of soil and morpho-physiological differences in maize under Eastern Himalayan region of India. Soil Tillage. Res. 134, 41–48 (2013).

Kumar, V. et al. Tillage, crop residue, and nitrogen levels on dynamics of soil labile organic carbon fractions, productivity and grain quality of wheat crop in typic Ustochrept soil. J. Pharmacognosy Phytochemistry. 7 (1), 598–609 (2018).

Bhattacharyya, R., Tuti, M. D., Kundu, S., Bisht, J. K. & Bhatt, J. C. Conservation tillage impacts on soil aggregation and carbon pools in a sandy clay loam soil of the Indian Himalayas. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 76 (2), 617–627 (2012).

Bono, A., Alvarez, R., Buschiazzo, D. E. & Cantet, R. J. C. Tillage effects on soil carbon balance in a semiarid agroecosystem. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 72 (4), 1140–1149 (2008).

Khambalkar., Priyadarshani, A., Tomar, P. S. & Verma, S. K. Influence of integrated nutrient management on carbon sequestration and its relationship with productivity of Pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum)-mustard (Brassica juncea) cropping sequence. Ind. J. Agron. 58 (4), 68–77 (2013).

Chivhane, S. P. & Bhattacharyya, T. Effect of land use and bio-climatic system on organic carbon pool of shrink-swell soils in Vidarbha region, Maharashtra. Agropedology 20 (2), 145–156 (2010).

Prasad, J. V. N. S. et al. Effect of ten years of reduced tillage and recycling of organic matter on crop yields, soil organic carbon and its fractions in Alfisols of semi-arid tropics of Southern India. Soil Tillage. Res. 156, 131–139 (2016).

West, T. O. & Post, W. M. Soil organic carbon sequestration rates by tillage and crop rotation: a global data analysis. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 66 (6), 1930–1946 (2002).

Babu, S. et al. Designing energy-efficient, economically sustainable and environmentally safe cropping system for the rainfed maize–fallow land of the Eastern Himalayas. Sci. Total Environ. 722, 137874 (2020).

Hazra, K. K. et al. Diversification of maize-wheat cropping system with legumes and integrated nutrient management increases soil aggregation and carbon sequestration. Geoderma 353, 308–319 (2019).

Parihar, C. M. et al. Long-term impact of conservation agriculture and diversified maize rotations on carbon pools and stocks, mineral nitrogen fractions and nitrous oxide fluxes in Inceptisol of India. Sci. Total Environ. 640, 1382–1392 (2018).

Vieira, F. C. B. et al. Carbon management index based on physical fractionation of soil organic matter in an acrisol under long-term no-till cropping systems. Soil Tillage. Res. 96 (1–2), 195–204 (2007).

Parihar, C. M. et al. Dependence of temperature sensitivity of soil organic carbon decomposition on nutrient management options under conservation agriculture in a sub-tropical Inceptisol. Soil Tillage. Res. 190, 50–60 (2019).

Patra, S. et al. Effect of conservation agriculture on stratification of soil organic matter under cereal-based cropping systems. Arch. Agron. Soil. Sci. 65 (14), 2013–2028 (2019).

You, D. et al. Short-term effects of tillage and residue on spring maize yield through regulating root-shoot ratio in Northeast China. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 13314 (2016).

Abdullah, A. S. Minimum tillage and residue management increase soil water content, soil organic matter and Canola seed yield and seed oil content in the semi-arid areas of Northern Iraq. Soil Tillage. Res. 144, 150–155 (2014).

Radicetti, E., Mancinelli, R., Moscetti, R. & Campiglia, E. Management of winter cover crop residues under different tillage conditions affects nitrogen utilization efficiency and yield of egg-plant (Solanum melanogena L.) in mediterranean environment. Soil Tillage. Res. 155, 329–338 (2016).

Jin, Y. H., Zhou, D. W. & Jiang, S. C. Comparison of soil water content and corn yield in furrow and conventional ridge sown systems in a semiarid region of China. Agric. Water Manage. 97 (2), 326–332 (2010).

He, J., Li, H., Kuhn, N. J., Wang, Q. & Zhang, X. Effect of ridge tillage, no-tillage, and conventional tillage on soil temperature, water use, and crop performance in cold and semi-arid areas in Northeast China. Soil. Res. 48 (8), 737–744 (2010).

Getahun, G. T., Munkholm, L. J. & Schjønning, P. The influence of clay-to-carbon ratio on soil physical properties in a humid sandy loam soil with contrasting tillage and residue management. Geoderma 264, 94–102 (2016).

Rusinamhodzi, L. et al. A meta-analysis of long-term effects of conservation agriculture on maize grain yield under rain-fed conditions. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 31, 657–673 (2011).

Ganapathi, S. et al. Studies on the effects of different tillage and weed management approaches on weed and growth parameters in maize crops and its influence on yield. Mysore J. Agricultural Sci. 56 (2), 121–128 (2022).

Ahmad, H., Shafi, M., Liaqat, W., Jan, M. F. & Rehan, W. Effect of tillage practices and weed control methods on yield and yield components of maize. Middle East. J. Agricultural Res. 7 (1), 175–181 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors are extremely thankful to All India Coordinated Research Project (AICRP) on weed management for the financial sponsorship received for the implementation and execution of this ongoing conservation agriculture experiment carried out at college farm, Professor Jayashankar Telangana State Agricultural University (PJTSAU), Rajendranagar, Telangana (India) under the aegis of “All India Coordinated Research Project on Long-Term Experiments.”

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The contributions of all authors must be described in the following manner; The authors confirm contribution to the manuscript as follows: study conception and design: K.N, R.P.T, P.B and J.G; data analysis and interpretation of results: K.N, M.A and M.B.N.Y: K.N and L.P.C; draft manuscript preparation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nthebere, K., Tata, R.P., Gudapati, J. et al. Assessment of conservation agriculture on soil nutrient’s stratification ratio, carbon sequestration rate, management indices and crop productivity in Southern Telangana India. Sci Rep 15, 15038 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00177-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00177-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

From scarcity to sustainability: agriculture intensification for food security and climate resilience in drylands

Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change (2025)