Abstract

The study on the parity of the radial profile of radial displacements due to MHD instabilities in magnetically confined torus plasmas is a crucial subject in fusion plasma research. In some experimental devices, only the parity transition from even to odd parity profile (even-to-odd parity transition) has been observed. Now, an odd-to-even parity transition is first observed after the even-to-odd parity transition in the Large Helical Device (LHD). Moreover, the odd-to-even and even-to-odd parity transitions repeatedly occur when the resonant magnetic perturbation (RMP) applied by external coils is large. The even parity profile is driven by the resistive interchange MHD instability, while the odd parity profile is driven by the “Edge” MHD instability. The even-to-odd and odd-to-even parity transitions are inferred to occur when the “Edge” instability becomes unstable and when it stabilizes under the unstable interchange instability, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Parity transitions in the radial profile of radial displacements evaluated from the plasma temperature and/or density fluctuation profiles due to MHD instabilities are sometimes observed in magnetically confined torus plasmas. The odd and even parity profile across a resonant surface is strongly associated with the topology of the magnetic container to confine plasmas. An odd-parity profile indicates the existence of a magnetic island. The island can significantly degrade the thermal insulation performance of the magnetic container, and, in the worst case, the growth of the islands leads to discharge terminations, so-called “disruptions”. Therefore, the study of the parity transition is one of the crucial subjects in fusion plasma research, as it is closely related to the appearance and disappearance of the island.

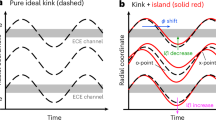

It is noteworthy that for radial displacement profiles with odd or even parity, there are only two possible parity transitions: from odd to even and from even to odd. It should be noted that the toroidal mode number (n) and poloidal mode number (m) remain unchanged during the parity transitions. In the previous experimental works on the parity transition, only the even-to-odd parity transitions have been reported. Roughly speaking, the behaviors of the even-to-odd parity transitions can be categorized into two groups. In the first group, the dominant parity quickly changes from even to odd through the collapse events, and the peak-to-peak distance (corresponding to “magnetic island width”) in the radial profile of fluctuation amplitude rapidly grows and saturates. They are observed before and after collapse events due to the resistive interchange mode in the negative magnetic shear operation of DIII-D tokamak1, due to the EIC (energetic ion-driven resistive interchange mode) growth2 in the Large Helical Device (LHD). In the second group, the magnetic fluctuation amplitude gradually increases over multiple cycles without any clear collapse events when the dominant fluctuation with even parity profile is present. Then, its profile switches from the even parity to the odd parity. This behavior has been observed when the neoclassical tearing instability grows after the formation of the seed island due to a sawtooth crash in tokamaks such as the ASDEX-U3,4 and the DIII-D5, before and after locked-mode-like instabilities occur in the LHD6, before and after the “Edge” MHD instability grows in the LHD7. Note that the “Edge” instability is defined as an odd parity mode that appears when the rational surface is located near the plasma boundary under low magnetic Reynolds number conditions.

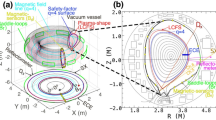

Previously observed parity transitions, as mentioned above, are transitions from even to odd parity. However, recently, a transition from odd to even parity is first observed in the LHD. This transition occurs only after the even-to-odd parity transition. Figure 1 shows the typical discharge of both even-to-odd and odd-to-even transitions observed in the LHD. The figure includes the time evolution of (a) the volume-averaged plasma beta value with heating power of NBIs, (b) the line-averaged electron density with the amount of gas puffing, (c) the magnetic fluctuation amplitude normalized by the operation magnetic field, and (d) the m/n = 1/1 external RMP coil current normalized by the operation magnetic field. The magnetic configuration is set to a magnetic axis torus location of 3.75 m, the toroidal field strength of 0.75 T, and plasma aspect ratio of 6.38. During the whole plasma discharge, a static external RMP with IRMP/Bt ~ 100 A/T is imposed, which corresponds to almost cancelling the intrinsic error field9. As shown in Figs. 1(a) and (c), the fluctuation amplitude is approximately 10 × 10− 5 in the initial phase of the discharge from t ~ 3.5 to 4.07 s, and it increases rapidly to about 50 × 10− 5 at t ~ 4.07 s, then the beta value decreases by about 13%. Note that the magnetic fluctuation amplitude of the m/n = 1/1 component is evaluated by root-mean-square for 5 ms. At t ~ 4.61 s, the fluctuation amplitude is reduced to about 10 × 10− 5 and the beta value recovers to the same level as in the initial phase of the discharge. Furthermore, after t ~ 4.86 s, an increase in fluctuation amplitude and a degradation of the beta value occur again, and after t ~ 4.96 s, a decrease in fluctuation amplitude and a recovery of the beta value take place once more. Note that the heating power is almost constant, and the electron density gradually changes from t = 3.5 to 5.3 s.

A typical discharge with the Edge MHD instability. (a) volume-averaged beta value (black line) and NBI heating power (red dotted), (b) line-averaged electron density (black) and voltage of piezo valve for hydrogen gas puffing (red dotted), (c) normalized magnetic fluctuation amplitude and (d) absolute value of normalized RMP coil current. Parameters in subplots (c) and (d) are normalized by the toroidal magnetic field. The hatched regions in the figures represent the time periods when the odd-parity mode is present.

Typical radial profiles of the amplitude and phase of density fluctuations during t ~ 3.5 to 4.07 s and t ~ 4.07 to 4.61 s are shown in Fig. 7(d1, e1) and (d3, e3) of Ref7. The amplitude and phase are evaluated from the line-integrated electron density fluctuations measured by a CO2 interferometer10. The channel spacing of the CO2 interferometer is approximately 0.01 m. The typical width of the even parity structure is about 0.04 m, while that of the saturated odd parity structure is about 0.05 m. Therefore, the distinction between even and odd parity structures can be reliably determined even from line-integrated data. It should be noted that ECE diagnostics are not available in the operational magnetic field range where the parity transition occurs. According to early works on the MHD instabilities of the LHD, the radial profile during t ~ 3.5 to 4.07s corresponds to the even parity, which is induced by the m/n = 1/1 resistive interchange MHD instabilities11,12, and that during t ~ 4.07 to 4.61 s corresponds to the odd parity, which is caused by the m/n = 1/1 “Edge” MHD instability7. The “Edge” instability occurs when the plasma beta and density are relatively high, and it reduces the confinement performance by 10–20%7. On the contrary, the resistive interchange instability reduces the confinement performance by less than 5%11. These results indicate a clear correlation between parity transitions and plasma confinement performance: the even-to-odd transition leads to confinement degradation, whereas the odd-to-even transition induces confinement improvement. The parity transitions are considered to result from the stabilization or destabilization of the ‘Edge’ instability under conditions where the resistive interchange mode remains unstable.

In this study, the density fluctuation amplitude is evaluated using the RMS value over a 5 ms time window. To detect short-time parity transitions that cannot be resolved from the density fluctuation profile alone, an alternative criterion based on the magnetic fluctuation amplitude evaluated over a shorter time window is used: the parity is considered odd when the magnetic fluctuation amplitude exceeds approximately 3 × 10− 4, and even when it is below this threshold.

Clarifying the conditions under which parity transitions occur is crucial because these transitions directly affect magnetic island formation and stability, significantly impacting plasma confinement and the operational stability of fusion devices. This paper reports on the first observation of odd to even parity transitions in LHD, aiming to clarify their triggers. The temporal evolution of magnetic island widths associated with parity transitions is examined in detail, and the influence of external RMP on the occurrence of parity transitions is also investigated. The results demonstrate that odd-to-even parity transitions, first observed in this study, occur more frequently at higher external RMP amplitudes, indicating that external magnetic perturbations potentially contribute to parity transitions associated with the stabilization of magnetic islands.

Results

With the experimental setup and parity definitions established, the temporal evolution of island widths associated with both types of parity transitions is quantified below.

Even-to-odd parity transition

First, the typical behavior of the even-to-odd parity transition is introduced in detail. Figure 2(a) shows the time evolution of the magnetic island width evaluated from the m/n = 1/1 radial magnetic fluctuation amplitude (Wmag) and that evaluated from the m/n = 1/1 line-averaged electron density fluctuation amplitude profile (Wpeak) around the even-to-odd parity transition in the discharge shown in Fig. 1. Here, the magnetic fluctuation amplitude is determined by calculating the difference between the maximum and minimum values within one cycle of the m/n = 1/1 magnetic fluctuation. The density fluctuation amplitude is derived as the root-mean-square of the density signals over a 5 ms interval and is updated every 1 ms. The former is based on the assumption that the perturbed current has a delta function centered around the resonant surface. The latter is the peak-to-peak distance of the line-averaged electron density fluctuation amplitude profile as shown by the hatched regions of Figs. 2(c1, c2). Figure 2(b) shows the frequency of the m/n = 1/1 fluctuation. The frequency is evaluated as the inverse of the period between the successive peaks in the m/n = 1/1 magnetic fluctuation. Before t = 4.06 s, the m/n = 1/1 magnetic fluctuation is already observed, and its amplitude and frequency remain constant. Around t ~ 4.06 s, the magnetic fluctuation amplitude gradually grows, and after 5 to 6 cycles, the Wpeak starts to rise as shown in Fig. 2(a). Figures 2(c1, c2) show the radial profiles of the line-averaged electron density fluctuation amplitude and phase difference with the magnetic fluctuation at t = 4.067 s just after the magnetic island is detected by the interferometer. Here, it should be noted that the minimum detectable value of the Wpeak is about 0.02 m (5% of the plasma minor radius), which corresponds to twice the channel spacing of the interferometer. The magnetic island width saturates approximately 10 ms after the beginning of the expansion. When the radial magnetic fluctuation is saturated, the Wmag is almost the same as the Wpeak. Note that the timescale for the magnetic island width to saturate is approximately equivalent to that for the neoclassical tearing mode to saturate after the formation of the seed island due to a sawtooth crash in the ASDEX-U3,4. The reason why almost the same growth time of magnetic islands, which are expected to have different formation mechanisms, remains a challenge for future research.

Behavior of the magnetic island from even to odd parity transition. (a) magnetic island widths evaluated from the radial magnetic fluctuation amplitude and the radial profile of electron density fluctuations, and (b) frequency of the m/n = 1/1 magnetic fluctuation. (c1)(c2) Radial profiles of amplitude and phase of electron density fluctuations after the even-to-odd parity transition. The hatched area represents the island location.

Odd-to-even parity transition

Next, the typical behavior of the odd-to-even parity transition is introduced in detail. Figures 3(a) and (b) show the time evolution of the magnetic island widths and the frequency of the magnetic fluctuation around the odd-to-even parity transition in the discharge shown in Fig. 1. Note that the radial profiles of the density fluctuation amplitude and phase difference for the odd and the even parity modes are similar to what was shown in Fig. 7(d3, e3) and (d1, e1) of Ref7, respectively. The Wpeak begins to decrease together with the reduction in magnetic fluctuation amplitude at t = 4.61 s, and the width becomes zero in 5 ms when the magnetic fluctuation amplitude stops decreasing at the value to 1/5, and the magnetic fluctuation continues to be observed. It should be noted that the time scale is less than by about half of that in the even-to-odd parity transition. During the even-to-odd transition, the frequency gradually decreases along with the increase in amplitude, but during the odd-to-even transition, the frequency drops abruptly as the magnetic island width begins to decrease.

External RMP effect on odd-to-even parity transition

In order to investigate the influence of the external RMP on the odd-to-even parity transition, experiments were conducted by varying the amplitude of the static RMP. The RMP coils in LHD consist of ten pairs of upper and lower coils. Three independent power supplies are available, allowing the application of RMPs with toroidal mode numbers such as n = 1 and n = 2. In this study, the main component of the external RMP has a mode number of m/n = 1/1, followed by m/n = 2/1 as the next dominant component. Figure 4 shows the number of odd-to-even parity transitions in discharges under the same experimental conditions, except for the RMP amplitude, for the period from t = 3.8 to 5.0 s with steady heating. The odd-to-even parity transitions, which result from the stabilization of the Edge instability, are indicated by a rapid decrease in the magnetic fluctuation amplitude. Note that the first even-to-odd parity transition is observed around t = 3.8 s, which corresponds to approximately 0.5 s after the start of heating, when the density is sufficiently high, and t = 5.0 s corresponds to 0.3 s before the heating is turned off. From Fig. 4, it is found that when IRMP/Bt exceeds 1500 A/T, the repetition frequency of odd-to-even parity transitions significantly increases. It should be noted that in discharges with 0 < IRMP/Bt < 2400 A/T, the external RMP does not penetrate into the resonant surface.

Figure 5 represents the time evolution of the volume-averaged beta value (a) and the root-mean-square amplitude of the magnetic fluctuation (b) in the discharge with an externally imposed RMP of 1870 A/T. Vertical dashed lines in Fig. 5 are the indicators of the odd-to-even parity transitions. The indicators are observed ten times from t = 3.8 to 5.0 s. Figure 5 shows that in the large RMP case, transitions between the even and odd parity occur much more frequently than in the small RMP cases.

(a) volume-averaged beta value (black line) and heating power (blue) and (b) the root-mean-square amplitude of the magnetic fluctuation in the discharge with |IRMP/Bt| ~ 1870 A/T. The hatched area corresponds to the time interval from t = 3.8 s to 5.0 s, during which the number of odd-to-even transitions is counted. Vertically dashed lines in the hatched area correspond to the occurrence of the odd-to-even parity transition.

Discussion

The above results show that odd-to-even transitions occur more frequently under large RMP; given that previous studies have demonstrated a strong dependence of the onset of “Edge” instability on plasma beta and magnetic Reynolds number (S), these findings are interpreted below in terms of beta–S trajectories. Figure 6 shows the trajectory of the time evolution of the volume-averaged plasma beta and the S around the resonant surface during the even-to-odd and odd-to-even parity transitions for both cases when the external RMP is small and large. In For the data points labeled “just before onset” and “just before stabilization” in Fig. 6, S is evaluated from the Thomson scattering data taken at 33 ms intervals, while the volume-averaged β is selected from its own signal, which is sampled at higher time resolution near the respective event timings. Therefore, the time stamps of β and S differ in these cases. In contrast, for the “saturated phase of collapse” and “saturated phase of beta”, both β and S are taken from the same Thomson scattering sampling timing. Note that the typical parity transition time is less than 10 ms, and the typical decay and recovery time of beta during the collapse and recovery for small RMP cases is approximately 60 ms and 40 ms, respectively. The symbols, ●, small ● and 〇 represent data points just before the even-to-odd parity transition, during the collapse, and in the saturated phase of the collapse, respectively. Similarly, ▲, small ▲ and △ indicate data points just before the odd-to-even parity transition, during the beta recovery, and in the recovered phase of the beta, respectively. Dotted lines indicate the temporal evolution during the even-to-odd parity transitions, and dash-dotted lines represent the temporal evolution during the odd-to-even parity transitions. Moreover, the blue symbols represent the small RMP cases, while the red symbols represent the large RMP cases. It is important to note, based on previous research7, that the even-to-odd parity transitions occur when the plasma beta is higher than a certain value and the S is lower than a certain value as shown by the gray closed circles of Fig. 6. According to Fig. 6, in the small RMP cases, after the even-to-odd parity transition, both the beta value and the S decrease. Subsequently, the beta value remains relatively constant while the S increases, and the odd-to-even parity transition occurs. After the odd-to-even parity transition, the beta value increases with the S remaining relatively constant. On the contrary, when the external RMP is large, the even-to-odd parity transition occurs in the region where both the beta value and S are larger than those of the small RMP cases. After the even-to-odd parity transition, the beta value decreases. Subsequently, the beta value decreases slightly, and then the odd-to-even parity transition occurs. After the odd-to-even parity transition, the beta value increases. During this period, the change in the S is almost constant, which is different from the small RMP cases. When the external RMP is large, the fact that the S decreases only slightly after the even-to-odd transition increases the likelihood of the odd-to-even transition, contributing to the frequent repetition of both transitions.

The volume-averaged plasma beta (<βdia> ) and the local magnetic Reynolds number around the resonant rational surface (S) during the even-to-odd and odd-to-even parity transitions. The symbols ○, small ● and ● represent data points just before the even-to-odd parity transition, during the collapse, and in the saturated phase of the collapse, respectively. Similarly, △, small ▲ and ▲ indicate data points just before the odd-to-even parity transition, during the beta recovery, and in the recovered phase of the beta, respectively. Blue (red) symbols correspond to data in discharges with |IRMP/Bt| < 120 A/T (> 1500 A/T), respectively. The grey closed symbols represent the threshold for the even-to-odd parity transition for small external RMP case.

Figure 7 presents the trajectories of local temperature and density during the even-to-odd parity transition. Each symbol represents the data in a single discharge. Blue indicates the case with relatively small external RMP, while red corresponds to the case with relatively large RMP. The open symbols represent data just before the onset of the instability, and the filled symbols represent data after the saturation of the collapse. In the small RMP case, a decrease in temperature leads to a reduction in both local beta and S.In contrast, in the large RMP case, both the temperature and density increase simultaneously, or the temperature remains nearly constant while the density decreases. In both situations, since the S is weakly dependent on density, the variation in S remains suppressed. This means that the impact of the odd parity mode on the local pressure for the large RMP case is smaller than that for the small RMP case.

After the even-to-odd transition under low RMP conditions, the observed temperature drop indicates a reduction in the temperature gradient caused by the magnetic island associated with the odd-parity mode. This weakened gradient may contribute to the gradual decrease in mode frequency observed during the even-to-odd transition, as seen in Fig. 2(c).

The trajectories of local density and temperature around the resonant surface during even-to-odd transitions for both low and high RMP cases as shown in blue and red symbols, respectively. The symbols differ for each discharge. The dashed lines and one-pointed chain lines correspond to the constant beta value and constant S, respectively.

The mode frequency at the island saturation for the large RMP case is slightly higher than for the small RMP case, but the saturated Wpeak is almost the same. This may be because of a high electron diamagnetic drift velocity, which is proportional to the local pressure gradient at the resonant surface. This suggests that the flattening width in the pressure profile is different depending on the amplitude of the external RMP even if a saturated island width is the same in both small and large RMP cases.

Figure 8 shows the time evolution of the magnetic island widths during a phase when both even-to-odd and odd-to-even parity transitions frequently occur in the discharge with the large RMP, while the beta does not fully recover. During the even-to-odd parity transitions of the phases, the growth time of the Wpeak is shorter than that in the small RMP cases. This is another reason why the parity transitions occur more frequently in large RMP cases. However, the reason for the shortened growth time of the Wpeak remains unclear. This is one of the future works.

Summary

In summary, on the parity of the radial profile of the radial displacement across a resonant surface in the magnetically confined torus plasmas, an odd-to-even parity transition is observed for the first time in the LHD. The transition is always observed after the even-to-odd parity transition, which is already observed in some torus plasmas. In the LHD, the repetition frequency of the transitions between the odd and the even parity increases when the amplitude of the RMP applied by external coils is large. Even-to-odd and odd-to-even parity transitions are inferred to be observed when the ”Edge” MHD instability and the resistive interchange MHD instability become dominant, respectively. On the contrary, in the other even-to-odd parity transition phenomena observed in the ASDEX-U, DIII-D, and so on3,4,5, the parity transitions occur following the non-linear processes of the MHD instabilities with the mode structure of the even parity. In these cases, the non-linear processes of the MHD instabilities with the odd parity structure should drive the generation of the MHD instabilities with the even parity structure. However, it would hardly occur. This is a hypothesis, which is a future subject. Moreover, during both parity transitions, it is not yet clear whether the two types of parity modes are mixed. Additionally, the influence of even parity modes on the occurrence of odd parity modes and the influence of odd parity modes on the occurrence of even parity modes are another future subject.

Methods

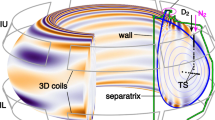

Large helical device

The Large Helical Device (LHD) is a magnetic confinement fusion experimental device where a magnetic container is generated by only coils. In the LHD, a magnetic island appears within the magnetic container when the plasma density is relatively high. Utilizing the high spatial-resolution interferometer installed in the LHD, detailed observations of the mode structure before and after the formation and stabilization of the magnetic island are achieved. This led to the discovery of not only even-to-odd parity transitions but also odd-to-even parity transitions in the radial structure of the MHD instability.

Radial profile measurement of plasma fluctuations

The radial profiles of temperature and density fluctuations driven by MHD instabilities are closely related to the presence of magnetic islands and the radial displacement profiles. When a magnetic island forms within the magnetic container, thermal insulation within the island is lost, resulting in pressure flattening in the island region. As the magnetic island passes through the pressure measurement region, pressure decreases on the core side of the island while increasing on the edge side. Since the magnetic island rotates with the plasma, when it moves out of the measurement region, the core-side pressure increases while the edge-side pressure decreases. Consequently, if a rotating magnetic island exists, radial profiles of temperature and density fluctuations with opposite phases around the magnetic island can be observed. Therefore, the parity of the radial profile of the fluctuations enables the inference of the presence of a magnetic island. Radial displacement profiles are also important parameters of MHD instabilities. The radial displacements are defined as the ratio of the pressure fluctuation to the gradient of the pressure equilibrium component.

External RMP coils

Auxiliary coils are used to apply magnetic perturbation to the magnetic container. The coils specifically used to apply resonant magnetic perturbations (RMP) are referred to as RMP coils. In magnetic confinement experimental devices, the stabilization of MHD instabilities through controlled magnetic perturbation has been demonstrated.

The RMP coils in LHD consist of ten pairs of upper and lower coils. Three independent power supplies are available, allowing the application of RMPs with toroidal mode numbers such as n = 1 and n = 2. In this study, the main component of the external RMP has a mode number of m/n = 1/1, followed by m/n = 2/1 as the next dominant component. In the LHD, it is discovered that when the amplitude of the external RMP exceeds a certain threshold, odd-to-even parity transitions occur more frequently.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the LHD data repository at https://doi.org/10.57451/lhd.analyzed-data.

References

Jayakumar, R. et al. Observation and analysis of a resistive mode with interchange parity in negative central shear plasmas in the DIII-D Tokamak. Phys. Plasmas. 9, 5043–5049 (2002).

Du, X. D. et al. Resistive interchange mode destabilized by helically trapped energetic ions and its effects on energetic ions and bulk plasma in a helical plasma. Nucl. Fusion 56, 016002 (2016).

Igochine, V. et al. Tearing mode formation induced by internal crash events at different Βn. Nucl. Fusion 57, 036015 (2017).

Igochine, V. et al. Conversion of the dominantly ideal perturbations into a tearing mode after a Sawtooth crash. Phys. Plasmas 21, 110702 (2014).

Igochine, V. et al. Seeding of neoclassical tearing modes by internal crash events in the ASDEX upgrade and DIII-D Tokamaks. Nucl. Fusion 59, 066038 (2019).

Takemura, Y. et al. Mode locking phenomena observed near the stability boundary of the ideal interchange mode of LHD. Nucl. Fusion. 52, 102001 (2012).

Takemura, Y. et al. Onset of instability with collapse observed in relatively high density and medium beta regions of LHD. Phys. Plasmas. 29, 092505 (2022).

Watanabe, K. Y. et al. Characteristics of MHD equilibrium and related issues on LHD. Fusion Sci. Technol. 58, 160–175 (2010).

Morisaki, T. et al. Flux surface mapping in LHD. Fusion Sci. Technol. 58, 465–470 (2010).

Tanaka, K. et al. Improvements of CO2 laser heterodyne imaging interferometer for Electron density profile measurements on LHD. Plasma Fusion Res. 2, S1033–S1033 (2007).

Watanabe, K. Y. et al. Effect of pressure-driven MHD instabilities on confinement in reactor-relevant high-beta helical plasmas. Phys. Plasmas 18 (2011).

Sakakibara, S. et al. MHD study of the reactor-relevant high-beta regime in the large helical device. Plasma Phys. Control Fusion. 50, 1–10 (2008).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the LHD experiment group for their excellent support. One of the authors (Y.T.) would like to thank Dr. K. Ida (NIFS) for useful discussions. This work was supported in part by the National Institute for Fusion Science under Grant No. KLPH004, by JSPS KAKENHI (No. 20K03910), and by a dispatch grant from the Future Energy Research Association.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.T. conceived the experiment. Y.T., K.W. and S.I. conducted the experiment. S.S. provided key measurements. Y.T. analysed the results. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Takemura, Y., Watanabe, K., Ito, S. et al. Parity transition of radial structure of MHD instability in magnetically confined torus plasmas. Sci Rep 15, 14890 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00181-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00181-5