Abstract

Over the past two decades, the method of controlling magnetic capsule robots for targeted drug delivery in gastrointestinal (GI) environments using external magnetic fields has been frequently discussed. In typical targeted drug delivery tasks, capsule robots must not only possess the ability to navigate across large obstacles but also adjust their orientation upon reaching the target site. However, most reported magnetic actuation systems struggle to simultaneously fulfill these two requirements. In this paper, we present a three-degree-of-freedom (3-DOF) semi-open closed-loop magnetic actuation system (SCMAS) for generating static gradient magnetic fields and dynamic rotating magnetic fields. By utilizing a BLE-IMU module to provide real-time feedback on the orientation of the internal permanent magnet and employing a PD controller for precise control, the SCMAS achieves both high accuracy and adaptability. We applied the SCMAS to a permanent magnet capsule robot and a capsule drug delivery robot, conducting multi-point drug delivery experiments in isolated porcine gastric tissues. The experimental results demonstrate that the SCMAS can achieve localized point-to-point orientation control and speed control over a wide range. This study may provide new insights into control strategies for magnetic capsule robots in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, the use of magnetic fields to control robots for targeted medical interventions inside the human body has become a prominent research focus in the field of robotics1,2,3,4,5. Compared to electromagnetic control systems6,7,8,9, permanent magnet actuator10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 (PMA) offer greater advantages in enabling large-scale and long-duration motion of robots18,19. By leveraging the magnetic gradient fields generated by permanent magnets and the rotating magnetic fields produced by specific rotational motions20, magnetic control systems can exert both magnetic gradient forces and magnetic torques on magnetic robots inside the human body21. Giovanni Pittiglio et al. proposed a dual External Permanent Magnet (dEPM) platform for magneto-mechanical manipulation, which optimizes the orientation of two permanent magnets mounted at the end of robotic arms. This system achieves a large workspace while enabling gradient-free fields in all three directions and control over five main independent gradient components22. Enjie Fang et al. introduced a hybrid electromagnetic actuation system integrating a pair of Helmholtz coils and three permanent magnets, enabling magnetic levitation control of capsule robots23.

Moreover, in the gastrointestinal (GI) environment, the presence of mucus and gastric folds24 makes the movement of robots particularly challenging. In our previous work, we designed a bio-inspired octopus sucker-structured targeted drug delivery robot, which utilized a rotating magnetic field in a one-dimensional motion direction to enable the magnetic soft robot to roll forward25. However, the motion path of the robot often lies within a two-dimensional plane and is highly susceptible to disturbances from the unknown GI environment. Therefore, there is a need for a control system capable of generating rotating magnetic fields in arbitrary directions within a two-dimensional plane.

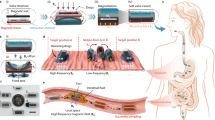

Overview of Semi-open Closed-loop Magnetic Actuation System (SCMAS) developed in this study. (A) Application on permanent magnet capsule robot: ideal orientation control and continuous point-to-point control. (B) SCMAS is composed of a “magnetic sphere” driven by three omni-directional wheels. (C) Exploded view of the magnetic sphere: embedded with a cylindrical permanent magnet and a BLE-IMU sensor module. (D) Application on capsule drug delivery robot: 2D navigation and targeted drug delivery.

In this paper, we propose a three-degree-of-freedom (3-DOF) semi-open closed-loop magnetic actuation system (SCMAS) (as shown in Fig. 1B,C) and mount it on a three-axis sliding platform for orientation control of a permanent magnet capsule robot (as shown in Fig. 1A) and motion control of a capsule drug delivery robot (as shown in Fig. 1D). Furthermore, by applying this control system and a drug delivery robot optimized for the GI environment to isolated porcine gastric tissue, efficient motion control and multi-point drug delivery of the robot can be achieved.

Our core contributions are listed below:

-

1.

A 3-DOF semi-open closed-loop magnetic control system, SCMAS, has been designed and constructed; the system is designed to control the attitude of permanent magnets and to realize static gradient magnetic field control and dynamic rotating magnetic field control at 3-DOF;

-

2.

The control performance of the SCMAS system was evaluated to realize point-to-point control and speed control;

-

3.

The practical application potential of SCMAS was explored by capsule drug release robot. 2D navigation and multi-target drug delivery experiments were performed on isolated porcine gastric tissue.

Results

The primary function of the SCMAS is to regulate the orientation of permanent magnets, thereby generating gradient magnetic fields and rotating magnetic fields in any desired direction within a three-dimensional space to facilitate the propulsion of capsule robots. To mitigate the impact of model inaccuracies and stochastic noise on the orientation of the permanent magnets during transmission, a BLE-IMU sensor module is affixed to the cylindrical permanent magnet, which is then housed within the magnet sphere. This module transmits the current orientation data of the permanent magnet to the host computer via Bluetooth communication. Given the inherent model errors and random noise present in the SCMAS, a PD controller is employed to achieve precise control over the orientation of the permanent magnets. Consequently, the SCMAS exhibits high-precision positional control capabilities within a three-dimensional space, along with a certain degree of velocity control proficiency.

Components of SCMAS and drug release coil

The mechanical construction of the SCMAS comprises a drive mechanism and a magnet sphere, as illustrated in Fig. 2A. Within the drive mechanism, three 42 Step motors, labeled 1 through 3, actuate corresponding omniwheels. To achieve a semi-open configuration that affords the system a larger operational workspace, the 42 Step motors numbered 1 and 3 are coupled to their respective omniwheels via a 90-degree planetary steering gear. Both the 42 Step motors and the planetary steering gears are securely fastened to the base using screws.

Within the magnet sphere, the assembly is anchored to the drive mechanism via the magnet sphere support. A cylindrical permanent magnet measuring \(\phi\)40*30 mm, along with a BLE-IMU module, is housed within a spherical casing of 60 mm in diameter. The spherical casing is composed of upper and lower sections that are joined by a threaded connection and mounted within the magnet sphere support. To minimize friction between the spherical casing and the magnet sphere support during rotation, the interior of the magnet sphere support is designed with recesses to accommodate copper beads. These copper beads facilitate the conversion of sliding friction into rolling friction, thereby enhancing the smoothness of the sphere’s motion.

The electrical control system of the SCMAS is bifurcated into an upper computer and a lower computer, as depicted in Fig. 2B. The lower computer employs an STM32F103 series MCU to generate frequency signals that actuate the step motor driver, thereby controlling the motion of the 42 step motors. Concurrently, it utilizes two ADC channels to acquire data from a rocker, which is instrumental in toggling between different motion modalities. The upper computer, operating on the ROS Noetic system, receives real-time orientation data of the magnet sphere from the BLE-IMU module and visualizes it through the Rviz module. Additionally, it computes the requisite rotational speeds for the omniwheels at any given moment using a PD controller. Communication between the upper and lower computers is facilitated via a serial interface.

When the SCMAS is applied to a capsule drug delivery robot, an alternating magnetic field is generated by an electromagnetic coil to control the oscillation of a magnet sheet housed within the capsule robot, thereby facilitating drug release. The alternating magnetic field is produced by amplifying a sinusoidal signal with a frequency modulated by the DAC of an STM32F407 series MCU, which is then powered by a DC motor driver to energize the electromagnetic coil.

Kinesiology of SCMAS

The SCMAS facilitates the orientation movement of the magnet sphere through the rotation of three omniwheels. Each omniwheel is equipped with five rollers along its periphery, which serve to filter out the motion of the magnet sphere in directions perpendicular to the rotation of the omniwheels26. Consequently, when establishing the kinematic model of the SCMAS, it is reasonable to approximate that the influence of each omniwheel on the magnet sphere is independent and cumulative.

The base coordinate system of the SCMAS and the rotational axes \(\varvec{a}_{\varvec{i}}\) of the omniwheels (described using the right-hand rule) are illustrated in Fig. 2C. The relationship between the angular velocity of the magnet sphere and the rotational speeds of the omniwheels can be expressed as follows (detailed derivation is provided in Note S1.):

Where \(\omega _i\left( i=1,2,3 \right)\) represents the magnitude of the angular velocities of the three omniwheels, and \(\varvec{\omega }_{\varvec{a}}\) denotes the vector form of the angular velocities of the three omniwheels. The symbols \(r_m\) and \(r_\omega\) correspond to the radii of the magnet sphere and the omniwheels, respectively. The three-dimensional vector \(\varvec{\omega }_{\varvec{m}}\) describes the angular velocity of the magnet sphere and can be used to represent any rotation of the magnet sphere within a three-dimensional coordinate system, as depicted in Fig. 2D.

According to the transformation relationship between angular velocity and ZYX Euler angular rates:

where \(\alpha\), \(\beta\) and \(\gamma\) correspond to the roll, pitch, and yaw angles of the magnet sphere, respectively, and the dotted notation above each variable signifies its time derivative. By integrating equation 1 with equation 2, the relationship between the rotational speeds of the omniwheels and the roll-pitch-yaw angular rates of the magnet sphere can be established. This relationship enables the control of the 3-DOF orientation of the magnet sphere through the application of a PD controller. The control logic block diagram of SCMAS is shown in Fig. 2E.

3-DOF point-to-point orientation control

In this section, we conducted tests on the point-to-point control capabilities of the SCMAS. For ease of description in the following text, we use a vector \(\left[ \alpha ,\beta ,\gamma \right]\), to represent the orientation coordinates of the magnet sphere in the roll-pitch-yaw coordinate system.

We marked a blue sticker directly above the initial orientation of the magnet sphere ([0, 0, 0]) and observed the position of the blue marker from a top-view perspective to illustrate changes in the magnet sphere’s orientation (as shown in Fig. 3A).

In the Original Point Regression test, the ideal pose of the magnet sphere was set to its initial orientation. After enabling the SCMAS, the magnet sphere sequentially moved from Point 1 to Point 6 and returned to its initial orientation (see Vid. S1). The error curves of the roll, pitch, and yaw angles during each point regression process are shown in Fig. 3C. According to the experimental data, the response time at 5% standard were approximately 2.2433s for \(\alpha\)(roll), 2.0333s for \(\beta\)(pitch) , and 2.5133s for \(\gamma\)(yaw); the response time at 2% standard were approximately 2.6367s for \(\alpha\)(roll), 2.6600s for \(\beta\)(pitch) , and 2.9467s for \(\gamma\)(yaw); the repeat positioning error were approximately 0.0041567rad for \(\alpha\)(roll), 0.0084833rad for \(\beta\)(pitch) , and 0.0070150rad for \(\gamma\)(yaw). (Detailed results see Note S3)

In the Original Point Regression and Rotation test, after returning to the initial orientation, the magnet sphere was commanded to rotate with an angular velocity direction of \(\omega =\left[ 0,0,-1 \right]\) (see Vid. S2). The variations in the roll, pitch, and yaw angles during the entire motion are depicted in Fig. 3D.

In the Multi-Point Control test, three target points were defined: Point 1 [0.75, 0.75, 0], Point 2 [0.75, − 0.75, 0], and Point 3 [− 0.75, − 0.75, 0]. The magnet sphere was controlled to move sequentially from the initial position to these three target points (see Vid. S3). The error curves of the roll, pitch, and yaw angles during the entire process are shown in Fig. 3E. The average steady-state errors were approximately 0.0119874 rad for \(\alpha\)(roll), 0.0117191 rad for \(\beta\)(pitch), and 0.0080835 rad for \(\gamma\)(yaw).

To demonstrate the capabilities of the SCMAS in applications involving permanent magnet capsule robots (such as WCE27,28,29,30,31), we embedded a cylindrical permanent magnet measuring \(\phi\)10*5mm into a capsule-shaped shell to simulate a permanent magnet capsule robot. The permanent magnet capsule robot was positioned 30mm above the top vertex of the SCMAS (as shown in Fig. 4A). The permanent magnet capsule robot resides within the magnetic field generated by the permanent magnet in the SCMAS. In Fig. 3B, we simulate the magnetic field distribution of the permanent magnet inside the magnet sphere by COMSOL, and the result is that the surface is capable of generating a maximum magnetic field of about 70 mT at the center of the plane 30 mm from the top vertex on the SCMAS.Under the influence of magnetic torque, the magnetic moment of the permanent magnet capsule robot aligns parallel to the direction of the magnetic field lines at its current position (as illustrated in Fig. 4B). Consequently, the orientation of the magnet sphere and the permanent magnet capsule robot exhibits an injective map relationship.

In the Capsule robot attitude rotation test, we first controlled the magnet sphere to the orientation [0.35, 0, 0] and then commanded it to rotate with an angular velocity direction of \(\omega =\left[ 0,0,-1 \right]\) (see Vid. S4). Correspondingly, the permanent magnet capsule robot also rotated around the vector [0, 0, − 1] (as shown in Fig. 4C).

In the Capsule Robot Orientation Control test, we defined three target points: Point 1 [0, 0.45, 0], Point 2 [− 0.45, 0.45, 0], and Point 3 [0.45, 0.45, 0]. The magnet sphere was controlled to move sequentially from the initial position to these three target points (see Vid. S5). During the orientation changes of the magnet sphere, the orientation of the permanent magnet capsule robot correspondingly changed to Pose 1, Pose 2, and Pose 3 (as depicted in Fig. 4D).

3-DOF speed control

We applied the SCMAS system to a capsule drug delivery robot to demonstrate its velocity control capabilities in three-dimensional space. The capsule drug delivery robot features a drug release port on its surface, which is sealed by a magnetic valve composed of two magnetic sheets with different magnetization directions (as shown in Fig. 5A). This design is primarily based on the structure described in reference29. The lower magnetic sheet has a small opening at the drug release port, while the upper magnetic sheet is solid. When the capsule drug delivery robot is in motion, the interaction force between the lower and upper magnetic sheets keeps the magnetic valve closed, preventing drug leakage. When the capsule drug delivery robot reaches the target site, an alternating magnetic field of a specific frequency causes the upper magnetic sheet to oscillate rapidly, opening the magnetic valve and releasing the drug.

Construction and 2D navigation of capsule drug delivery robot. (A) General view of capsule drug delivery robot. (B) Construction of capsule drug delivery robot. (C) Control relationship of SCMAS and capsule drug delivery robot. (D) Angle change for speed control with 2 omniwheels. (E) Angle change for speed control with 3 omniwheels. (F) 2D navigation of capsule drug delivery robot.

The permanent magnet in the SCMAS generates a magnetic torque on the lower magnetic sheet as it rolls, causing the capsule drug delivery robot to roll accordingly (as shown in Fig. 5C). By mounting the SCMAS on a three-axis sliding platform, the capsule drug delivery robot can be navigated in a two-dimensional plane. This is achieved by translating the SCMAS within the x-y plane while controlling the magnet sphere to roll with an angular velocity direction perpendicular to the direction of motion.

The fabrication process of the capsule drug delivery robot is illustrated in Fig. 5B. A mold with the shapes of the lower and upper magnetic sheets was created using SLA printing. A mixture of neodymium iron boron magnetic powder and Ecoflex 00-50 in a 1:1 ratio was thoroughly stirred and then injected into the mold. The surface was leveled using a scraper. The mold was left to stand at 50 °C for 50 min to allow the lower and upper magnetic sheets to cure. Subsequently, the lower and upper magnetic sheets were fixed in a magnetizer according to the required magnetization directions for magnetization.

Application of SCMAS and capsule drug delivery robot for multi-target drug delivery in isolated porcine gastric tissues. (A) Conceptual diagram of multi-target drug delivery. (B) Experimental scenes and descriptions. (C) Conceptual diagram of targeted drug delivery. (D) Optimized architecture of capsule drug delivery robot for GI environments. (E) Drug release from a capsule drug delivery robot in simulated gastric fluid under an alternating magnetic field with an amplitude of 30 mT and a frequency of 10 Hz. (F) Multi-target drug delivery in isolated porcine gastric tissues.

Finally, the magnetized lower and upper magnetic sheets were installed into the SLA-printed capsule drug delivery robot shell, and epoxy resin was applied at the positions indicated in Fig. 5B. After securing the lower and upper magnetic sheets, the upper and lower shells of the capsule drug delivery robot were bonded together using epoxy resin. Once the epoxy resin had cured, a magnetic torque was applied to the capsule drug delivery robot to open the magnetic valve, and drugs were injected using a syringe.

In the previous discussion on the kinematics of the SCMAS, we based our analysis on the assumption that the rollers installed on the edges of the omniwheels can filter out the motion of the magnet sphere in directions perpendicular to the rotation of the omniwheels. However, in practice, the omniwheels and the magnet sphere do not interact solely through the rollers. When non-roller parts of the omniwheels come into contact with the magnet sphere, the resistance to driving the magnet sphere by the other omniwheels increases, inevitably leading to some degree of slippage.

In point-to-point control, the error-based PD controller can compensate for the errors induced by slippage, thereby achieving relatively high positional control accuracy. However, during speed control, such slippage can cause unsteady motion and errors in the movement of the magnet sphere.

We conducted a comparison between SCMAS systems utilizing two omniwheels and three omniwheels. In both systems, the magnet sphere was initially rotated at a speed of \(\pi\) rad/s around the axes \(\left[ -1,0,0 \right]\),\(\left[ -\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2},0,-\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \right]\) and \(\left[ \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2},0,-\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \right]\), respectively. Subsequently, the rotational speed was increased to \(2\pi\) rad/s. The angular variation curves are shown in Fig. 5D,E. The results indicate that the SCMAS can achieve higher control precision during speed control by sacrificing one degree of freedom.

The SCMAS can perform navigation control of the capsule drug delivery robot within a two-dimensional plane, as illustrated in Fig. 5F. To demonstrate the navigation capabilities of the SCMAS system in a two-dimensional plane, we constructed a maze using FDM printing (as shown in Fig. 5F). Initially, the capsule drug delivery robot was placed at the red dot as the starting point. The SCMAS system, mounted on a three-axis sliding platform, was used to drive the capsule drug delivery robot sequentially to the black, blue, and green dots within the maze (see Vid. S8). This demonstrates the potential application of the SCMAS in targeted drug delivery.

To further demonstrate the capability of SCMAS in targeted drug delivery, we designed targeted drug delivery experiments in isolated porcine gastric tissues. The SCMAS navigated the capsule drug delivery robot to reach multiple drug delivery targets and controlled the capsule drug delivery robot for drug release via electromagnetic coils to realize multipoint targeted drug delivery (as shown in Fig. 6A,C).

In Fig. 6E, we injected water mixed with green dye into the chamber of the previously prepared capsule drug delivery robot and placed it in simulated gastric fluid. Under the influence of a magnetic field with an amplitude of 30 mT and a frequency of 10 Hz, the vibration of the upper magnetic sheet promoted the exchange of internal and external fluids, causing the denser dye to continuously flow out along the direction of gravity.

In experiments using isolated porcine gastric tissues, we conducted multi-point drug delivery tests. The mucus and gastric folds on the surface of the porcine gastric tissue made the movement of the capsule drug delivery robot quite challenging. Inspired by the structure of sea urchins33, we used hot melt adhesive to create similar spike-like structures on the surface of the capsule drug delivery robot (as shown in Fig. 6D). This modification enhanced its ability to overcome obstacles and move forward in high-viscosity fluids while rolling on the gastric wall surface.

In Fig. 6B, the SCMAS was mounted at the end of a three-axis sliding platform, and an electromagnetic coil for generating an alternating magnetic field was installed at the end of an FR5 robotic arm. In Fig. 6F, the capsule drug delivery robot was navigated in two dimensions using the SCMAS and the three-axis sliding platform. After reaching Drug Release Point 1 from the initial position, the FR5 robotic arm moved the electromagnetic coil above the capsule drug delivery robot to generate an alternating magnetic field, thereby controlling drug release. The release of the drug was primarily achieved through the diffusion of liquids between the internal and external environments as the magnet valve repeatedly opened. As the FR5 robotic arm moved away, the drug delivery process ceased. Subsequently, the capsule drug delivery robot was navigated to Drug Release Point 2, and the above procedure was repeated to complete drug delivery at the second point.

Conclusion

In this study, we designed and developed a three-degree-of-freedom (3-DOF) semi-open closed-loop magnetic actuation system (SCMAS). The SCMAS enables point-to-point control and speed control by manipulating the orientation of an internal permanent magnet. For point-to-point control, we conducted tests including Original Point Regression, Original Point Regression and Rotation, and Multi-Point Control, and applied the SCMAS system to the orientation control of a permanent magnet capsule robot. For speed control, we analyzed the precision of the SCMAS under two-wheel and three-wheel driving configurations and performed two-dimensional navigation experiments using the SCMAS system with a capsule drug delivery robot. Finally, we conducted multi-point targeted drug delivery experiments within isolated porcine gastric tissues. During the experimental process, we realized that the actual clinical application of the capsule robot has further difficulties compared with the ex vivo simulation experiments, such as the capsule robot’s position can not be directly sensed, and the more complex intestinal environment, etc. Through the flexible endoscopy32 or make the capsule robot itself with the ability of sensing the surrounding environment34, it can help us to better complete the task of targeting the drug delivery. In the future, we plan to explore more efficient omnidirectional wheel structures and control algorithms, and further explore the potential of SCMAS for applications within the fields of soft magnetic robots and magnetic fiber robots35,36.

Methods

Construction of SCMAS

The base and supporting structures of the SCMAS were primarily fabricated using an FDM printer (X1-Carbon, Bambu Lab, China) with PLA material (PLA Sparkle, Bambu Lab, China). The 42 Step motor and corresponding step motor drivers were sourced from Xingyi Electronic Technology, China. The framework of the omniwheels was crafted using CNC machining (JLC, China), while the rollers and connecting components were 3D-printed using TPU material (TPU 95A, Bambu Lab, China).

Inside the magnet sphere, the spherical shell was manufactured using white resin via SLA printing (9600, JLC, China). The cylindrical permanent magnet is an N45 magnet with a diameter of 40 mm and a thickness of 30 mm. The BLE-IMU module (IM600, Chenyi Electronic Technology, China) communicates with the upper computer through a Bluetooth serial module (BLE serial module) (TR100, Chenyi Electronic Technology, China).

The upper computer is a PC (FX707ZR, ASUS, China) running Ubuntu 22.04, equipped with an i7-12700H CPU (Intel, USA) and an RTX3070 GPU (Nvidia, USA). The ROS Noetic system is operated on the upper computer to simultaneously run node programs for IMU data reception and unpacking, PD controller (PD controller) calculations, and communication with the lower computer. The lower computer is a minimal system board based on the stm32f103C8T6 microcontroller (ST, Italy).

The three-axis sliding platform used to mount the SCMAS was provided by Fanggong Intelligent, China.

Construction of drug release coil

The drug release coil, used to open the magnet valve of the capsule drug delivery robot, was wound with enameled wire of 0.8 mm diameter, consisting of 800 turns, and internally equipped with FeNi alloy (Jiangsu National Nickel New Material Technology, China). The DC motor driver (model AQMD6020NS-E2B) used to drive the coil was provided by Akelc, China. The MCU used to generate the sinusoidal signal is the stm32f407VET6 (ST, Italy). During the drug delivery experiments in isolated porcine gastric tissues, the alternating magnetic field applied had an amplitude of 40 mT and a frequency of 20 Hz.

Construction of permanent magnet capsule robot and capsule drug delivery robot

The outer shells of the permanent magnet capsule robot and the capsule drug delivery robot were fabricated using transparent photosensitive resin (Clear V5 Resin, Formlabs, USA) via an SLA printer (Form 4L, Formlabs, USA). The permanent magnet inside the permanent magnet capsule robot is made of N54 grade of NdFeB.

The molds used to prepare the magnet sheets for the capsule drug delivery robot were created using white photosensitive resin (White V5 Resin, Formlabs, USA) via an SLA printer (Form 4L, Formlabs, USA). The magnet sheets were composed of silicone rubber (Ecoflex\(^{\textrm{TM}}\) 00-50, Smooth-On, USA) and NdFeB particles (MQFP-15-7, Magnequench, Canada) mixed in a 1:1 ratio. The prepared magnetic sheets were fixed in a capacitive pulse power supply (J1801N) according to the required magnetization direction and magnetized under a pulsed magnetic field of approximately 1.8 T. After magnetization, the high coercivity of the NdFeB particles ensured that the magnetic sheets exhibited stable magnetic moments. The epoxy resin used to bond the magnet sheets to the outer shell was provided by 3M, USA.

Data availability

All data that support the plot within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ze, Q. et al. Spinning-enabled wireless amphibious origami millirobot. Nat. Commun. 13, 3118 (2022).

Zhang, X., Chen, G., Fu, X., Wang, Y. & Zhao, Y. Magneto-responsive microneedle robots for intestinal macromolecule delivery. Adv. Mater. 33, 2104932 (2021).

Liu, X. et al. Magnetic living hydrogels for intestinal localization, retention, and diagnosis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2010918 (2021).

Li, X., Zhao, F., Rong, W., Li, D. & Xie, H. A mucoadhesive magnetic millimeter-scale robot with two motion modes for drug delivery to the colon. Appl. Mater. Today 35, 101941 (2023).

Keller, H. et al. Method for navigation and control of a magnetically guided capsule endoscope in the human stomach. In 2012 4th IEEE RAS & EMBS International Conference on Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics (BioRob), 859–865 (IEEE, 2012).

Cai, M. et al. Performance-guided rotating magnetic field control in large workspaces with reconfigurable electromagnetic actuation system. IEEE Trans. Robot. (2024).

Song, L. et al. Motion control of capsule robot based on adaptive magnetic levitation using electromagnetic coil. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 20, 2720–2731 (2022).

Kummer, M. P. et al. Octomag: An electromagnetic system for 5-dof wireless micromanipulation. IEEE Trans. Robot. 26, 1006–1017 (2010).

Nguyen, K. T. et al. A composite electro-permanent magnetic actuator for microrobot manipulation. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 229, 107516 (2022).

Liao, Z. et al. Accuracy of magnetically controlled capsule endoscopy, compared with conventional gastroscopy, in detection of gastric diseases. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14, 1266–1273 (2016).

Yang, Z. & Zhang, L. Magnetic actuation systems for miniature robots: A review. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2, 2000082 (2020).

Armacost, M. P. et al. Accurate and reproducible target navigation with the stereotaxis niobe® magnetic navigation system. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 18, S26–S31 (2007).

Guo, X., Pan, K., Wang, Q. & Wen, Y. Robust adaptive sliding-mode control of a permanent magnetic spherical actuator with delay compensation. IEEE Access 8, 128096–128105 (2020).

Xu, Y., Li, K., Zhao, Z. & Meng, M.Q.-H. Adaptive simultaneous magnetic actuation and localization for wce in a tubular environment. IEEE Trans. Robot. 38, 2812–2826 (2022).

Ryan, P. & Diller, E. Magnetic actuation for full dexterity microrobotic control using rotating permanent magnets. IEEE Trans. Robot. 33, 1398–1409 (2017).

Salmanipour, S. & Diller, E. Eight-degrees-of-freedom remote actuation of small magnetic mechanisms. In 2018 IEEE international conference on robotics and automation (ICRA), 3608–3613 (IEEE, 2018).

Sakuma, H. Three-dimensional motion control of an untethered magnetic object using three rotating permanent magnets. Sci. Rep. 13, 18052 (2023).

Du, X. & Yu, J. Image-integrated magnetic actuation systems for localization and remote actuation of medical miniature robots: A survey. IEEE Trans. Robot. 39, 2549–2568 (2023).

Ebrahimi, N. et al. Magnetic actuation methods in bio/soft robotics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2005137 (2021).

Mahoney, A. W. & Abbott, J. J. Generating rotating magnetic fields with a single permanent magnet for propulsion of untethered magnetic devices in a lumen. IEEE Trans. Robot. 30, 411–420 (2013).

Keller, H. et al. Method for navigation and control of a magnetically guided capsule endoscope in the human stomach. In 2012 4th IEEE RAS & EMBS International Conference on Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics (BioRob), 859–865 (IEEE, 2012).

Pittiglio, G. et al. Collaborative magnetic manipulation via two robotically actuated permanent magnets. IEEE Trans. Robot. 39, 1407–1418 (2022).

Fang, E., Wang, J. & Song, S. A magnetic actuation system based on electromagnetic coils and permanent magnets for controlling capsule robot. In 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics (ROBIO), 1665–1669 (IEEE, 2024).

Greenwood-Van Meerveld, B., Johnson, A. C. & Grundy, D. Gastrointestinal physiology and function. Gastrointest. Pharmacol. 1–16 (2017).

Tong, D. et al. Octopus-inspired soft robot for slow drug release. Biomimetics 9, 340 (2024).

Wright, S. E., Mahoney, A. W., Popek, K. M. & Abbott, J. J. The spherical-actuator-magnet manipulator: A permanent-magnet robotic end-effector. IEEE Trans. Robot. 33, 1013–1024 (2017).

Chen, W., Sui, J. & Wang, C. Magnetically actuated capsule robots: A review. IEEE Access 10, 88398–88420 (2022).

Ye, D., Zhang, F., Yuan, S., Song, S. & Meng, M. Q.-H. Magnetically driven wireless capsule robot with targeting biopsy function. In 2019 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics (ROBIO), 1222–1227 (IEEE, 2019).

Valdastri, P., Simi, M. & Webster, R. J. III. Advanced technologies for gastrointestinal endoscopy. Ann. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 14, 397–429 (2012).

Shamsudhin, N. et al. Magnetically guided capsule endoscopy. Med. Phys. 44, e91–e111 (2017).

Munoz, F., Alici, G., Zhou, H., Li, W. & Sitti, M. Analysis of magnetic interaction in remotely controlled magnetic devices and its application to a capsule robot for drug delivery. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 23, 298–310 (2017).

Sun, Y. et al. Magnetically driven capsules with multimodal response and multifunctionality for biomedical applications. Nat. Commun. 15, 1839 (2024).

Mateos, L. A. Bionic sea urchin robot with foldable telescopic actuator. In 2020 IEEE/ASME International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics (AIM), 1063–1068 (IEEE, 2020).

Iakovidis, D. K. et al. Deep endoscopic visual measurements. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 23, 2211–2219 (2018).

Fan, J. et al. Magnetic fiber robots with multiscale functional structures at the distal end. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2309424 (2024).

Zhao, Y. et al. Microgripper robot with end electropermanent magnet collaborative actuation. Micromachines 15, 798 (2024).

Acknowledgements

All authors would like to acknowledge the support from Robot and Microsystem Research Center of Soochow University. Y. C. and D. T. would like to acknowledge the support from Hui-Chun Chin and Tsung Dao Lee Chinese Undergraduate Research Endowment (CURE).

Funding

This work was supported in part by National Key Research and Development Project under Grant 2023YFB4705300, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62422313, 62103294, and 61925304, and Hui-Chun Chin and Tsung Dao Lee Chinese Undergraduate Research Endowment (CURE).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y. C. and D. T. conceived and designed the research. Y. C. constructed mechanical and electrical control system for SCMAS. Y. Z. designed and constructed the capsule drug delivery robot. X. F. and T. C. directed the project. All authors wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Source of isolated porcine gastric tissues

The isolated porcine stomach tissue used in the multipoint targeted drug delivery experiments was provided by bache farmer’s market from China.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information 2.

Supplementary Information 3.

Supplementary Information 4.

Supplementary Information 5.

Supplementary Information 6.

Supplementary Information 7.

Supplementary Information 8.

Supplementary Information 9.

Supplementary Information 10.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Y., Tong, D., Zhao, Y. et al. SCMAS: an IMU-based 6-DOF closed-loop permanent magnet actuation system for magnet agent. Sci Rep 15, 17808 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00320-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00320-y