Abstract

Quality of life (QoL) is a crucial factor which has to be taken into account in the treatment of vestibular schwannomas. This study compared microsurgical and radiosurgical treatments, focusing on three. (1) evaluating post-treatment clinical outcomes, (2) assessing the effect on QoL and (3) analyzing complication rates, particularly in geriatric patients. In this retrospective study, 586 patients underwent either microsurgery or gamma knife radiosurgery between 1990 and 2013. Demographic and treatment data were collected, including quality of life (QoL) assessments using the Short Form 36 (SF-36) and evaluations of the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS). Complication rates were also analyzed. The study included 194 microsurgery patients and 392 radiosurgery patients. Radiosurgery patients showed significantly better postoperative hearing and facial nerve function (p < 0.05). QoL scores were higher in the radiosurgery group for physical and emotional role functioning, while microsurgery patients (including aged 65 years and older) reported better scores for bodily pain and general health perceptions. Neurological complications were 41.9% in the microsurgery group, most of them being permanent (92.9%). Radiosurgery generally showed better preservation of hearing, facial nerve function, and quality of life compared to microsurgery, although both treatments appeared equally effective in older patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Minimizing treatment burden and preserving the patients’ quality of life (QoL) is, besides tumor control, paramount in vestibular schwannoma management1. While treatment options to achieve complete tumor removal or long-term tumor control have evolved, the treatment priority remains unchanged: avoiding complications and safeguarding patients’ QoL2. Current strategies to achieve these goals are multidisciplinary and personalized. Microsurgery by a suboccipital-retrosigmoid approach utilizing intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring (IOM)-guidance as well as gamma knife radiosurgery (GKRS) are well established treatment standards. Both, however carry relevant treatment-associated risks3,4. In this context, recent literature suggests that microsurgery may initially negatively impact QoL with subsequent improvement seen over time, while GKRS has a less negative effect with minimal change during follow-up on patients’ QoL5. Still, there is no consensus on which aspects of QoL are most affected or the role of factors such as tumor size, cranial nerve function and age6. With regards to the latter, evidence shows that the geriatric subpopulation (> 65 years) is particularly vulnerable to treatment-associated complications since pre-existing comorbidities and patient frailty complicate treatment and recovery7. However, vestibular schwannomas are known to cause significant disabilities in the elderly when left untreated7,8. In this context, the SF-36 has been the most widely used comprehensive measure of QoL and a valuable tool for comparing outcomes across different treatment modalities throughout different age groups9. By retrospectively analyzing data spanning over two decades, this study aimed to compare the effects of microsurgical and GKRS treatment of vestibular schwannomas on QoL and treatment-associated complication rates.

Methods

Patients and outcome analysis

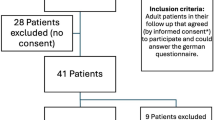

This was a retrospective study conducted at a single interdisciplinary center. Following approval from the institutional review board (EK 125/16) the tumor registry was queried from February 1990 to November 2013 for patients who underwent either microsurgery or GKRS for unilateral vestibular schwannoma at an academic interdisciplinary center. Patients who were previously treated with radiotherapy were excluded from this analysis. Clinical outcome analysis focused on caudal cranial nerve (CN) function (i.e. CN V, CN VI, CN VII, CN VIII and CN IX impairment), the incidence of hydrocephalus/shunt dependency and gait ataxia. Facial nerve function was assessed by the House-Brackmann Facial Nerve Grading System: grades I-III were considered good facial function10. Hearing function was differentiated into normal hearing, hypacusis, and normal hearing as assessed by pure tone and speech audiometry11. Furthermore, the presence of patient reported tinnitus was recorded. The patients’ QoL analysis was performed by the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36). Additionally, the patients’ functional status was assessed by the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) and treatment-associated complications were recorded.

Treatment

The treatment modality for all patients was recommended on a case-by-case basis by an interdisciplinary neurooncological tumor board. All patients who underwent microsurgery were operated using the retrosigmoid-suboccipital approach as previously described and IOM was routinely used in all procedures12. In brief, GKRS was performed using a Leksell Gamma Knife model B (Elekta Instrument AB, Stockholm, Sweden)13. Multishot-dose plans were created to construct a radiation field conformal with the tumor shape. Treatment planning was performed using Leksell Gamma Plan (Elekta Instrument AB) as described previously14. The median applied dose was 12.7 Gy (range 11.0–14.0 Gy).

Data collection

Tumor size was measured radiographically using contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance (MR) imaging (see illustrative case in Fig. 1). At least two senior neuroradiologists independently evaluated the tumor sizes in a blinded manner preoperatively, 6 months post-treatment and at the final follow-up. Clinical-neurological follow-up assessments were conducted at discharge and 3 to 6 months post-treatment, including evaluations of CN function as well as assessments for hydrocephalus and ataxia. Separate analyses were performed for elderly patients aged 65 years and older. SF36 evaluation was performed 9–12 months after treatment (median 10.5 months).

Statistical analysis

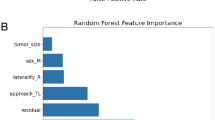

Data were checked for consistency and normality using Saphir-Wilks test. Fisher’s Exact test or Pearson’s Chi Squared test were used to analyze cross tabulations. In case of normal distributions, independent t-tests were used, otherwise bootstrap-t tests to compare means. Marginal homogeneity test was used to test the change of tumor sizes (smaller, stable, larger) over time. Linear and logistic regression analyses were also applied and illustrated using Scatterplots. All reported tests were two-sided, and p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses in this report were performed by use of STATISTICA 13 (Hill, T. & Lewicki, P. Statistics: Methods and Applications. StatSoft, Tulsa, OK) and PASW 27 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0., Armonk, NY). Data analysis was performed as per protocol and all statistical analyses were performed by a biostatistician (WH).

Results

Patients

The total study population consisted of 586 patients (308 females) with a median age at treatment of 57.5 years (IQR 47–68 years) and a mean KPS of 89.6 ± 5.8 prior to treatment. The microsurgery cohort consisted of 194 (33.1%) cases and 392 (66.9%) patients were treated by GKRS. Among patients who underwent GKRS were 17.6% cases who had undergone prior surgery and in accordance with the inclusion criteria no patients had received prior radiotherapy. The median pre-treatment KPS was 90.2 ± 9 and 89.3 ± 3.1 respectively, for the microsurgery and GKRS groups (p = 0.18). Patients who underwent microsurgery had larger tumors (2.6 vs. 1.8 cm3; p < 0.0001) and more often of female sex (59.8 vs. 49%; p = 0.017). Furthermore, patients aged 65 years and older were more common (24.2 vs. 36.4%; p = 0.03) among the GKRS cohort (data summarized in Table 1).

With regard to CN functions the following status were recorded prior to treatment: the share of patients with hypacusis and anacusis were 62.9% and 33% in the microsurgery cohort and the respective rates were 74.1% and 22.8% in the GKRS cohort. Thus, pre-treatment anacusis was significantly more common in patients treated by surgery (p = 0.009). Normal hearing function and tinnitus prior to treatment were equally distributed (p > 0.05). Good facial nerve function was seen in 193 (99.5%) patients of the microsurgery cohort and 376 (96.4%) patients of the GKRS cohort (p = 0.016; Tables 2 and 3). No pre-treatment differences in CN V, CN VI and CN IX function as well as incidence of hydrocephalus and ataxia between cohorts were detected (all p > 0.05) In the subgroup of patients > 65years, hydrocephalus was more frequent in the microsurgery group preoperatively (17% vs. 4.9%; p = 0.01), but not postoperatively (3% vs. 8%; p = 0.43). The same was seen for ataxia both before and after treatment overall.

Functional impairment and QoL

Performance status measured by the KPS remained consistent across groups both before and after treatment, showing virtually no change. Neither being 65 years or older nor having a higher tumor volume were prognostic factors for low KPS throughout the follow-up period (p = 0.84 and p = 0.73 for all groups). Quality of life data, measured using the SF-36, revealed that patients in the microsurgery group reported higher QoL scores at the last follow-up (median 10.5 years) for “bodily pain” and “general health perceptions” in comparison to the gamma knife radiosurgery group, both overall and in patients aged 65 years and older. The radiosurgery group showed overall better scores for “physical functioning,” “physical role functioning,” and “emotional role functioning” (data summarized in Table 4). Neurological complications were 41.9% in the microsurgery group. Most of them were permanent (92.9%). In the radiosurgery group, the proportion of those whose tumors decreased in size increased from 15.4% (6 months) to 28.9% (last follow-up; p < 0.00001).

Discussion

Key findings

Vestibular schwannomas require careful treatment planning to balance tumor control with preservation of neurological function and QoL15. Our study focused on comparing outcomes between microsurgery and radiosurgery, revealing several key findings: (1) GKRS demonstrated superior postoperative hearing and facial nerve preservation, (2) QoL scores, particularly in physical and emotional role functioning, were higher in the radiosurgery group, and (3) neurological complications were more common and often permanent in the microsurgery cohort.

Clinical outcome

Regarding hearing and facial nerve function, our results align with existing literature that underscores the advantages of radiosurgery and reports about its CN VII preservation rates16,17. However, when reviewing the data from the geriatric subgroup only (65 years and older), no significant differences in postoperative outcomes for facial nerve function, hearing preservation, and complications related to CN VI and CN IX impairments between the two treatment modalities could be seen. This is in line with previous studies suggesting that older age does not necessarily compromise the surgical outcomes of vestibular schwannoma treatments18,19. The influence of age on outcomes is multifaceted and might be affected by co-morbidities in older patients or compensatory mechanisms in younger ones. The timing of postoperative assessments may also play a role, as later assessments may reflect complications or age-related frailty, making direct comparisons difficult.

Our analysis of QoL, as assessed by SF-36, revealed notable distinctions between the two treatment modalities. Patients undergoing GKRS consistently reported higher QoL scores in physical and emotional role functioning compared to those treated with microsurgery. This might suggest that radiosurgery may offer patients better functional outcomes, i.e. maintaining daily activities and emotional well-being post-treatment. Conversely, microsurgery patients reported higher QoL scores in domains related to bodily pain and general health perceptions. This might imply that microsurgery could offer advantages in terms of pain management and overall health perceptions. Of note, patients aged 65 years and older who underwent microsurgery reported higher QoL scores in domains related to bodily pain and general health perceptions as well. This might indicate that despite potentially higher complication rates, the geriatric subpopulation may experience less discomfort and have a better overall perception of their health status post-treatment compared to their counterparts who underwent radiosurgery. Ultimately, it is possible that factors such as dizziness, tinnitus and facial nerve deterioration play a significant role in impacting quality of life, particularly in physical and emotional functioning. Additionally, hearing loss could further contribute to these challenges, but these hypotheses warrant further investigation.

Limitations

This study is limited by its retrospective design and the long timeframe (1990–2013). Consequently, advancements in surgical and radiosurgical techniques may influence current outcomes, limiting the applicability to present-day practices2. Moreover, SF-36 data were only collected postoperatively and not preoperatively for all patients, which limits the ability to assess changes in quality of life attributable to the treatment itself. Nevertheless, our data emphasize the significance of tailored treatment decisions, particularly for older patients suffering from vestibular schwannomas.

Conclusions

This study underscores the benefits of GKRS in preserving hearing, facial nerve function, and certain quality of life aspects, while microsurgery excels in pain management and general health perceptions. Future studies incorporating recent data are needed to reflect advancements and ultimately improve patient outcomes.

Data availability

All data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Guillemin, F., Puechmaille, M., Khalil, T. & Biau, J. The recent management of vestibular schwannoma radiotherapy: A narrative review of the literature. J. Clin. Med. 13, 1611. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13061611 (2024).

Carlson, M. L., Link, M. J. & Vestibular Schwannomas N Engl. J. Med. 384, 1335–1348 https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra2020394 (2021).

Fík, Z. et al. Hearing after vestibular schwannoma surgery: Is it preserved forever?? Otol Neurotol. 44, 260–265. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0000000000003801 (2023).

Shin, Y. et al. Neurotological complications after radiosurgery versus conservative management in acoustic neuromas: A systematic review-based study. Acta Otolaryngol. 123, 59. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016480310000822 (2003).

Papatsoutsos, E. & Spielmann, P. M. Self-evaluated quality of life and functional outcomes after microsurgery, stereotactic radiation or observation-only for vestibular schwannoma of the adult patient: A systematic review. Otol Neurotol. 39, 232–241. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0000000000001664 (2018).

Carlson, M. L. et al. Long-term quality of life in patients with vestibular schwannoma: An international multicenter cross-sectional study comparing microsurgery, stereotactic radiosurgery, observation, and nontumor controls. J. Neurosurg. 123, 1059–1071. https://doi.org/10.3171/2014.10.JNS141028 (2015).

Helal, A. et al. Differential impact of advanced age on clinical outcomes after vestibular schwannoma resection in the very elderly: Cohort study. Oper. Neurosurg. (Hagerstown). 21 (3), 104–110. https://doi.org/10.1093/ons/opab170 (2021).

Dörner, L. et al. Age, preoperative tumor volume and widening of the internal acoustic meatus are independent factors associated with poor preoperative hearing in vestibular schwannoma patients - results of a single-center retrospective analysis. Neurosurg. Rev. 47 (1), 262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-024-02419-8 (2024).

da Cruz, M. J., Moffat, D. A. & Hardy, D. G. Postoperative quality of life in vestibular schwannoma patients measured by the SF36 health questionnaire. Laryngoscope 110, 151–155. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005537-200001000-00027 (2000).

House, J. W. & Brackmann, D. E. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 93 (2), 146–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/019459988509300202 (1985).

Gardner, G. & Robertson, J. Hearing preservation in unilateral acoustic neuroma surgery. Ann. Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 97 (1), 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/000348948809700110 (1988).

Basma, J. et al. History, variations, and extensions of the retrosigmoid approach: Anatomical and literature review. J. Neurol. Surg. B Skull Base. 83 (Suppl 2), e324–e335. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0041-1729177 (2022).

Bailo, M. et al. Gamma knife radiosurgery as primary treatment for large vestibular schwannomas: Clinical results at long-term follow-up in a series of 59 patients. World Neurosurg. 95, 487–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2016.07.117 (2016).

Huffmann, B. C., Reinacher, P. C. & Gilsbach, J. M. Gamma knife surgery for atypical meningiomas. J. Neurosurg. 102 (Suppl), 283–286. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.2005.102.s_supplement.0283 (2005).

Goldbrunner, R. et al. EANO guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of vestibular schwannoma. Neuro Oncol. 22 (1), 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/noz153 (2020).

Tatagiba, M. et al. A comparative study of microsurgery and gamma knife radiosurgery in vestibular schwannoma evaluating tumor control and functional outcome. Neurooncol Adv. 5 (1), vdad146. https://doi.org/10.1093/noajnl/vdad146 (2023).

Aman, R. A., Petonengan, D. A. A., Hafif, M. & Santoso, F. Hearing preservation, facial nerve dysfunction, and tumor control in small vestibular Schwannoma: A systematic review of gamma knife radiosurgery versus microsurgery. J. Clin. Neurol. 19 (3), 304–311. https://doi.org/10.3988/jcn.2022.0116 (2023).

Strickland, B. A. et al. Surgical outcomes following vestibular schwannoma resection in patients over the age of sixty-five. J. Neurol. Surg. B Skull Base. 84 (2), 129–135. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1771-0504 (2023).

Van Abel, K. M., Carlson, M. L., Driscoll, C. L., Neff, B. A. & Link, M. J. Vestibular Schwannoma surgery in the elderly: A matched cohort study. J. Neurosurg. 120 (1), 207–217. https://doi.org/10.3171/2013.6.JNS122433 (2014).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows. Study conception and design: A.R., C.B.; data collection: A.R., B.H., C.B.; analysis and interpretation of results: A.R., C.S., W.H., C.B.; draft manuscript preparation: A.R., B.H., C.S., R.A.K., H.C., C.B. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board (EK 125/16) and the need for a formal informed consent to participate was waived by the IRB given the retrospective nature of this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Romagna, A., Schwartz, C., Huffmann, B. et al. Analysis of quality of life and outcomes of vestibular schwannoma patients after resection and radiosurgery in an interdisciplinary treatment concept. Sci Rep 15, 15941 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00372-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00372-0