Abstract

Biological sex determination is essential for analyzing human skeletal remains in archaeology, anthropology, and forensic science. This study investigates whether Raman spectroscopy of intact human dental enamel can be used as a non-destructive method for sex estimation. Orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) and logistic regression identified sex-specific spectral characteristics in 88 human teeth from 47 modern individuals (26 females, 21 males). The OPLS-DA model showed excellent performance, with R2Y(cum) = 0.943 and Q2Y(cum) = 0.895. Raman shift wavenumbers at 373, 1182, and 1600 cm−1 were identified as the most reliable discriminators and included in a final logistic regression model. This model achieved an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC-AUC) of 0.98, a sensitivity of 0.87, and a specificity of 0.94. Our results indicate that Raman spectroscopy can effectively differentiate male and female human dental enamel based on subtle differences in molecular composition—possibly linked to residual differences between AMELX and AMELY-derived proteins. This non-destructive, rapid, and reliable method offers a valuable alternative for sex determination in contexts where chemical analysis is impractical or sample preservation is critical and holds promise for future applications in archaeological and forensic material.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Determining biological sex is essential in archaeology and anthropology for reconstructing population dynamics, social structures, migration patterns, and health, as well as for exploring gender roles in ancient and modern contexts1. Accurate sex determination is also critical in forensic settings, for example, in victim identification at crime scenes or mass disasters and for providing evidence in legal proceedings2.

Traditional methods of sex estimation focus on morphological and osteometric analyses of skeletal features, particularly the pelvis, and cranium3,4,5,6. However, these approaches become less reliable when remains are fragmented, belong to subadult individuals, lack comparative reference data, or are poorly preserved, underscoring the need for alternative techniques7,8,9.

Molecular advances have introduced more sophisticated tools for sex determination. DNA-based methods are widely used for various tissues10,11,12,13,14,15, with bones and teeth especially valued for their durability and resistance to environmental degradation16,17,18,19. A common DNA target is the dimorphic amelogenin gene, located on the X (AMELX) and Y (AMELY) chromosomes, which encode sex-specific variants of a structural protein of dental enamel. These sex-specific nucleotide variations can be detected by PCR and electrophoresis20,21,22,23,24. The amelogenin protein plays a critical role in tooth enamel formation, with AMELX and AMELY variations traceable to specific amino acid differences25,26 (Figure 1; Table 1). Advanced proteomic techniques can identify these sex-specific peptide sequences1,27.

However, molecular applications in archaeology, anthropology, and forensics face two main challenges: (1) the preservation of endogenous biomolecules and (2) the risk of contamination from exogenous sources. Ancient DNA analysis is particularly sensitive to degradation and contamination10,28. In contrast, proteins—especially in enamel—tend to preserve better, often for millions of years29,30,31. Proteomics can thus succeed in cases where DNA analysis fails32. Nonetheless, DNA and proteomic methods require destructive sampling, specialized laboratory facilities, and complex protocols, which may be prohibitive when sample preservation is paramount or resource availability is limited1,26,27,33.

Raman spectroscopy provides a promising non-destructive alternative. By detecting molecular vibrations via inelastic light scattering, Raman spectroscopy produces a detailed molecular “fingerprint” without damaging the sample (Figure 1)34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41. It has been successfully applied to a variety of biological tissues, including bone and dental structures. Recent studies have demonstrated its use in sex determination of dental tissues, but often involve destructive sampling of dentin or cementum or lack a clear molecular explanation for observed differences42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51.

To date, no studies have systematically investigated sex determination using Raman spectroscopy on fully intact dental enamel. However, as the most durable biological tissue, dental enamel is a logical candidate for such analyses—particularly given its acellular, inert nature throughout life52,53 and the known persistence of enamel-derived peptide fragments over evolutionary timescales1,27,29.

We present a non-destructive method for sex determination using Raman spectroscopy of intact human enamel, validated on juvenile teeth with confirmed biological sex extracted during routine orthodontic procedures. Spectral data were analyzed using multivariate classification techniques—orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) and logistic regression—to identify sex-specific Raman shift wavenumbers potentially associated with differences in AMELX and AMELY isoforms1,22,27.

Differences in peptide sequence are known to influence protein properties such as hydrophobicity, polarity, and aromatic content, which affect folding and structure—and, in turn, their Raman signatures46,47. We hypothesize that Raman spectroscopy captures molecular fingerprints, which reflect variations between AMELX and AMELY isoforms, thereby offering a promising, non-invasive approach for biological sex determination, particularly where destructive sampling is not feasible.

Although this study focused on modern teeth, the cost-effective and reproducible protocol we present lays the groundwork for future applications in archaeological, forensic, and clinical contexts. By demonstrating the feasibility of non-destructive sex determination using Raman spectroscopy on intact dental enamel, our method addresses a key challenge in the analysis of rare or valuable specimens. It expands the current toolkit with a scalable approach that combines molecular sensitivity with sample preservation—offering new possibilities for research in the life sciences and beyond.

Enamel development and sex determination using Raman spectroscopy. Amelogenin is the principal matrix protein found in dental enamel and is essential for its development. During enamel formation, amelogenin assembles into nanospheres with a hydrophobic core and a hydrophilic, negatively charged outer layer. These nanospheres organize into higher-order structures that serve as a scaffold for hydroxyapatite crystal growth before being partially degraded during enamel maturation. Amelogenin is encoded by two genes: AMELX (on the X chromosome) and AMELY (on the Y chromosome). Due to sequence variations, the resulting protein isoforms exhibit structural differences that can be used for biological sex determination through proteomic analysis1,27. Our method applies Raman spectroscopy, a widely used, non-destructive physicochemical technique based on inelastic light scattering, to detect vibrational modes of both organic and inorganic components in enamel. When a monochromatic light source (such as a visible or near-infrared laser) interacts with molecular bonds in a sample, most scattered light remains at the same wavelength (Rayleigh scattering), while a small fraction undergoes inelastic scattering (Raman scattering), producing wavelength shifts corresponding to specific molecular vibrations54. We hypothesize that the sequence differences between AMELX and AMELY isoforms contribute to the spectral variation observed between sexes. By leveraging these spectral features, our approach offers a non-destructive means of estimating biological sex. This proof-of-concept was developed using intact modern human teeth and lays the groundwork for future applications. Open source images taken from Wikimedia Commons55,56.

Results

Spectroscopy and data preprocessing

A total of 88 teeth were analyzed, comprising 66 permanent and 22 deciduous teeth. Most permanent teeth were premolars (n = 64), consistent with their frequent extraction for orthodontic purposes; two incisors were also included. Among primary teeth, molars (n = 20) were most common, followed by canines (n = 2). The mean age at the time of extraction was 12.70 ± 2.13 years for males and 12.22 ± 1.89 years for females, with a combined group mean of 12.46 ± 2.02 years.

Raman spectra were acquired from all 88 teeth using a portable 785 nm Raman spectrometer coupled to a 20× video microscope, covering a spectral range of 65–3351 cm−1. After baseline correction using a locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS), the spectra were normalized based on the intensity of the 580 cm−1 peak, corresponding to the ν4 PO42−(asymmetric bending) mode of hydroxyapatite47,57. This normalization accounts for variations in signal intensity and ensures consistency across samples. Following visual inspection, 24 spectra were excluded as outliers, resulting in a final dataset of 240 high-quality spectra.

Mean Raman spectra from male and female enamel samples showed prominent peaks between 200 and 1700 cm−1, attributed to inorganic (phosphate) and organic (protein and lipid) components (Figure 2)57.

Raman spectra of human dental enamel. This figure displays the mean Raman spectra of dental enamel from female (top, blue) and male (bottom, red) samples, with shaded areas representing 95% confidence intervals. Two light grey insets highlight representative sections of each average spectrum, enlarged three-fold to improve the visibility of confidence intervals.

Orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA)

OPLS-DA was used to separate predictive spectral variation (associated with sex) from orthogonal (non-predictive) variation. The full spectral range (200–3350 cm−1) was retained without band pre-selection or dimensionality reduction. After testing different numbers of orthogonal components, the final model consisted of one predictive and six orthogonal components, accounting for 92.2% of total spectral variance (R2X(cum) = 0.922) and 94.3% of variance in the response variable (R2Y(cum) = 0.943). Predictive ability was high (Q2Y(cum) = 0.895), with a root mean square error of estimation (RMSEE) of 0.121. Figure 3 shows a clear group separation along the predictive component (t[1]P), and Figure 4a illustrates the performance plateau at six orthogonal components. Permutation testing (n = 100) yielded p-values of 0.01 for R2Y and Q2Y, confirming statistical significance (Figure 4b).

OPLS-DA scores plot demonstrating separation between male and female dental enamel samples. The scatter plot shows the first predictive component (t[1]P, x-axis) and the first orthogonal component (tO[1], y-axis). Each point corresponds to a Raman spectrum, color-coded by biological sex (red = females, blue = males). Shaded ellipses indicate 95% confidence intervals. Clear separation along t[1]P suggests discriminative spectral differences between sexes.

OPLS-DA model performance and statistical validation. (a) Cumulative explained variance (R2Y, gray bars) and predictive ability (Q2Y, black bars) across 1 to 6 orthogonal components. Both metrics increased with added components, plateauing at five to six, suggesting model stability. (b) Permutation test with 100 random label assignments. Observed R2Y and Q2Y values (solid squares) exceeded all permuted values (diamonds), indicating statistical significance (p = 0.01).

Spectral feature selection

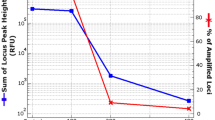

Further analysis with the OPLS-DA model aimed to identify reliable spectral features for sex differentiation. Three metrics were extracted to assess each wavenumber’s relevance: predictive loadings, which indicate how strongly a wavenumber contributes to the model’s classification axis; variable importance in projection (VIP) scores, which summarize each wavenumber’s overall influence across all components of the model; and orthogonal loadings from the six orthogonal components, which capture variation unrelated to class separation. The orthogonal loadings were normalized, weighted by their explained variance, and summed to produce cumulative weighted orthogonal loadings, reflecting non-discriminative signal contributions. Both predictive and cumulative orthogonal loadings were normalized to a 0–1 scale to allow direct comparison (Figure 5a). VIP scores were also normalized and plotted alongside the loading metrics to support visual interpretation of each wavenumber’s overall relevance in the model.

An index was calculated for each wavenumber, which is defined as the absolute difference between normalized predictive and cumulative weighted orthogonal loadings (Index = |Predictive| – |Orthogonal|; Figure 5b) to quantify discriminative strength. Wavenumbers with high index values were considered robust discriminative features, combining strong class-separating potential with low noise sensitivity. Local maxima in the index curve exceeding a threshold of 0.25 were selected as reliable features. The resulting peaks (Table 2) correspond to Raman shifts associated with phosphate vibrations, C–H bending in organic constituents, and amide bands, suggesting compositional and structural sex-related differences in dental enamel.

Identification of key spectral features for sex differentiation in dental enamel. (a) Spectral metrics over 200–3350 cm−1: normalized predictive loadings (blue) show each wavenumber’s contribution to sex classification; cumulative weighted orthogonal loadings (red) reflect noise-related variation; and normalized VIP scores (purple) indicate overall variable importance. Wavenumbers with high predictive and low orthogonal loadings are considered reliable discriminators. (b) The index plot displays the absolute difference between predictive and orthogonal loadings (Index = |Predictive| – |Orthogonal|). Peaks with local maxima above 0.25 (black dots) are labeled by wavenumber and predictive loading, marking key Raman shifts for sex differentiation (Table 2). These results underscore Raman spectroscopy’s potential for accurate, non-destructive sex identification in dental enamel.

Logistic regression model

Using the ten highest-ranking peaks from the index analysis, we trained a logistic regression model to predict biological sex. The dataset was randomly split into a training set (70%) and a test set (30%). Four peaks (373, 1182, 1197, and 1600 cm−1) emerged as statistically significant predictors (p < 0.05), with coefficients of 14.4087 (p = 0.040681), −78.1089 (p = 0.016529), 49.6110 (p = 0.045181), and 95.0144 (p = 0.000155), respectively. Due to spectral proximity between 1182 and 1197 cm−1, only the more significant 1182 cm−1 peak was retained in the final model to reduce multicollinearity.

The final model included three predictors: 373, 1182, and 1600 cm−1. It achieved an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.98 for the receiver operating characteristic (ROC), reflecting excellent discriminative ability (Figure 6), sensitivity of 0.87 (male samples correctly identified by the model), and specificity of 0.94 (female samples correctly identified). The final logistic regression equation was:

Samples with p ≥ 0.5 were classified as male; those with p < 0.5 were classified as female.

ROC curve showing the predictive performance of the logistic regression model. The ROC curve evaluates the refined model based on three Raman shifts (373, 1182, and 1600 cm−1) for sex classification in dental enamel. Sensitivity (true-positive rate) is plotted against 1 − specificity (false-positive rate) across thresholds (blue curve). The diagonal line represents chance-level performance (AUC = 0.5). The logistic regression model achieves an AUC of 0.98, signifying excellent discriminative capability. The model correctly identified 87% of male samples (sensitivity) and 94% of female samples (specificity).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that Raman spectroscopy integrated with OPLS-DA and logistic regression reliably differentiates male from female human dental enamel rapidly and non-destructively. By targeting key Raman shift wavenumbers, our logistic regression model achieved a cross-validated area under the curve (AUC) of 0.98 (via internal cross-validation) with a sensitivity of 0.87 and a specificity of 0.94, enabling straightforward prediction of biological sex from enamel spectra. The logistic regression equation predicts the probability that a sample is male (probability ≥ 0.5) or female (probability < 0.5).

We used modern, taphonomically unaltered teeth to establish a controlled reference baseline of known biological sex. This foundational step is critical before applying the method to archaeological or fossil material, where biomolecular preservation is expected to be more variable. Our work aligns with previous studies, such as Gamulin et al., who applied Raman spectroscopy to the cementum at the tooth apex and the dentin at the cervical region (dentin-enamel junction), or Banjšak et al., who used destructive sampling of dentin for sex determination46,47. In contrast, our focus on intact enamel—where amelogenin, the key protein in enamel formation, is most directly relevant—not only simplifies the procedure while preserving the sample but can potentially exploit the long-term stability of enamel proteins even over geological time scales29. Unlike bone or dentin, enamel is an acellular and avascular tissue that does not remodel after eruption52. While amelogenin and other structural proteins are largely enzymatically degraded during enamel maturation, residual peptide fragments—including those differing between the AMELX and AMELY protein variants—become embedded in the hydroxyapatite lattice and remain stable in the inert enamel matrix throughout life53. In enamel’s protective environment, these peptides may persist for millennia post-mortem, as demonstrated by their successful identification in archaeological and fossil teeth through proteomic analysis1,29.

Except for caries, post-eruptive changes to enamel are largely restricted to superficial enamel and are limited to ion exchange and remineralization processes affecting the outermost ~ 10–20 μm. These surface dynamics do not alter the deeper enamel architecture or degrade embedded proteins within the prismatic structure58. Using a 785 nm excitation wavelength in Raman spectroscopy allows spectral acquisition from subsurface enamel well beyond the zone of superficial alteration. The resulting vibrational spectra capture signals from mineral (phosphate, carbonate) and organic components, including the residual protein matrix. This is consistent with prior studies demonstrating the capacity of Raman spectroscopy to detect organic signatures in mature enamel54,57,59,60. Thus, Raman-based detection of biological sex-related signatures in mature enamel is feasible and likely transferrable to ancient specimens.

Our analysis of the predictive and orthogonal loadings from the OPLS-DA model identified several Raman shift wavenumbers that effectively differentiate between sex, including the peaks at 373 cm−1, 1182 cm−1, and 1600 cm−1 as key predictors. In the following paragraphs, we discuss the potential underlying molecular mechanisms. To contextualize the statistical findings, we propose that these Raman shifts reflect underlying molecular and structural differences between AMELX and AMELY isoforms, influencing how proteins integrate with enamel crystallites during formation. We interpreted the sex-specific signals directly from intact enamel without using isolated amelogenin peptide standards for reference. We aimed to develop a non-invasive, in situ method that reflects the protein–mineral interactions in their native environment. Synthetic peptide standards do not capture the conformational constraints or mineral matrix embedding that influence Raman signal generation.

The Raman shift at 373 cm−1is associated with the symmetric bending of phosphate in the inorganic hydroxyapatite, the primary mineral phase in enamel47,61. If AMELX and AMELY exhibit distinct susceptibilities to cleavage or generate slightly different cleavage products, this would change their spatiotemporal distribution within the developing enamel layer. Such differences could alter how (and when) proteins interact with growing enamel crystallites and thus lead to variations in crystal organization. Consequently, the final mineral structure—including features detectable by Raman spectroscopy (e.g., subtle shifts in specific vibrational peaks)—may differ based on which amelogenin isoform predominates and how efficiently it is degraded during key stages of enamel maturation.

The 1182 cm−1Raman shift is linked to C–H bending vibrations within the organic component62 Variations in the primary sequences of AMELX and AMELY include differences in amino acids, often leading to alterations in a protein’s secondary and tertiary structures or aggregation states. In particular, proline is known to influence protein folding significantly. It is often called a “helix breaker” due to its rigid ring structure, which introduces kinks into α-helical regions (54). If AMELX contains a higher frequency of proline residues than AMELY, as some sequence alignments suggest, these residues could disrupt the secondary structure differently in the two isoforms. Such structural differences in amelogenins can, in turn, alter how these proteins integrate into the enamel matrix, influencing local vibrational modes.

The Raman shift at ~ 1600 cm−1may be attributed to amide I or II vibrations (C=O stretching, N–H bending, and C–N stretching)54,63,64 and aromatic ring modes. While phenylalanine is often highlighted, tyrosine, tryptophan, and histidine can also contribute signals in this region54,62, reflecting a combination of different molecular vibrations. Differences in the AMELX and AMELY protein sequences could influence the configuration of these amide bonds and the overall protein conformation. Beyond the notable insertions in AMELY (e.g., the 14 amino acid insertion from residues 35–48, methionine at residue 59), sequence disparities in proline content can also contribute to variations in protein folding and vibrational spectra. This may alter backbone and side-chain interactions within the enamel matrix, ultimately producing subtle but detectable shifts in the amide I/II region (~ 1600 cm−1) of the Raman spectrum. Hence, proline—a seemingly minor difference in amino acid composition—could be an important factor underpinning the distinct vibrational signatures observed for AMELX versus AMELY65.

By linking the identified Raman shifts to AMELX and AMELY isoforms, we highlight the critical role of protein–mineral interactions in enamel and propose a molecular basis for the observed spectral variation. This understanding is further supported by high-resolution Raman spectroscopy studies, showing that differences in enamel mineralization and the organic matrix can lead to detectable spectral features57. This insight not only supports the reliability of Raman-based sex determination but also underscores why intact enamel is the logical target for such analyses.

Despite these promising findings, several limitations and caveats merit discussion. First, the sample size (88 teeth from 47 individuals), though sufficient for proof-of-concept, may not fully capture the variability in enamel composition across diverse populations or age groups. Moreover, using anonymized samples precludes correlating spectral differences with factors such as age, social status, diet, or health—variables that may also influence enamel composition. Additionally, despite the high accuracy demonstrated by our OPLS-DA and logistic regression models, the limited sample size and number of predictors may still pose a risk of overfitting. The specific sample type may also limit the generalizability of our findings. Only modern samples (primarily adolescent teeth with short post-eruption times) were studied. The specificity of the identified spectral features for distinguishing male and female samples could vary depending on the enamel preservation state and exposure to environmental factors. Thus, studies with larger, more diverse sample sets are necessary to validate these findings across different contexts and improve their broader applicability.

Future research should expand the sample set to improve statistical power and validate our findings across a broader demographic and preservation spectrum, including archaeological and forensic specimens. Another promising avenue is the application of Raman spectroscopy to other biological materials, such as hair or nails, to assess its broader utility in identifying biological traits and personal identification. Additionally, integrating advanced machine learning algorithms - such as support vector machines (SVM), neural networks, or ensemble methods - may further improve the accuracy of sex determination and uncover additional informative spectral features not evident through conventional analysis.

Given its portability, rapid data acquisition, and non-destructive nature, Raman spectroscopy is well suited for on-site applications during excavations or forensic investigations, particularly when conventional methods are constrained by sample preservation or ethical considerations. Our findings thus establish a foundation for expanding the use of Raman spectroscopy in sex determination, with promising implications for anthropological, paleontological, forensic, and even clinical contexts.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates that Raman spectroscopy is a reliable, non-destructive tool for sex determination in human dental enamel, leveraging distinct spectral signatures that likely reflect variations in AMELX and AMELY peptide sequences. Several specific Raman shift wavenumbers emerged as significant predictors for biological sex, providing a robust physicochemical foundation for sex differentiation. A key advantage of Raman spectroscopy is its non-destructive nature, which preserves valuable samples and bypasses the need for extensive preparation or chemical treatment. With its potential for rapid, in situ analysis, this method has the potential to complement existing approaches across multiple disciplines. While this proof-of-concept study focused on modern teeth, it lays the groundwork for future applications—from forensic casework to the analysis of ancient, prehistoric, or even fossilized human remains. Validation across broader populations, age groups, and varying preservation states will be critical for assessing the method’s broader utility. With continued refinement, Raman spectroscopy may open new avenues for non-invasive bioarchaeological and forensic investigations, contributing to a deeper understanding of human developmental biology and evolution.

Methods

Provenance and permissions statement

This study was conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and ethical regulations. A prospective review by the Zurich Cantonal Ethics Commission (KEK) concluded on February 21, 2020 (BASEC No. 2020-00288) that the project does not fall under the scope of the Swiss Human Research Act (HRA), as it involves no new interventions on human subjects or collection of fresh human tissue.

The analyzed teeth were drawn from an anonymized medical collection held at the Institute of Evolutionary Medicine (IEM), consisting of approximately 200 human teeth extracted between 1986 and 1992 by the School Dental Service of the Canton of St. Gallen (Switzerland) during routine orthodontic treatment. The collection was originally assembled for an unpublished study on post-Chernobyl radioisotope deposition. At the time of collection, all samples were anonymized and labeled only with date of birth, sex, and extraction date.

A total of 88 teeth were selected for analysis. As this material was collected before current Swiss human research regulations, informed consent was not obtained at the time of collection and was not required retrospectively. The KEK Zürich confirmed that no additional approvals or permissions were necessary under Swiss law. All specimens remain curated within the IEM’s recognized anatomical collection, ensuring long-term preservation and compliance with institutional and national standards.

Raman spectroscopy data acquisition

Raman spectra were obtained using a portable Raman spectrometer (i-Raman Plus, B&W Tek, Newark, Delaware, USA) coupled with a video microscope (BAC151, B&W Tek) providing 20× magnification. The spectrometer operated with a 785 nm excitation wavelength, covering a spectral range from 65 to 3351 cm−1. To optimize spectral quality while preventing sample damage, the laser power was set to 20% of its maximum output, with an integration time of 120 s for each measurement. Three measurements were taken from different regions of visually healthy tooth crown enamel for each sample, resulting in 264 spectra. Dark scans with identical integration times were subtracted from the measurements to correct for background noise.

Data preprocessing

Several preprocessing steps were implemented to prepare the Raman spectra for analysis. Baseline correction was performed using a locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) function to eliminate background fluorescence and other baseline effects. Following this, the spectra were normalized using the intensity of the 580 cm−1 peak, which corresponds to the ν4 PO42−(asymmetric bending) mode47. This peak is characteristic of the phosphate structure in hydroxyapatite and is prominently featured in enamel due to its highly organized crystalline nature. This normalization method ensures consistency and comparability across spectra. It distinguishes enamel from other biological hard tissues, such as bone, which typically shows a weaker 580 cm−1 peak and a more substantial 590 cm−1peak57. Additionally, wavenumbers below 200 cm−1 were excluded because of inconsistencies and challenges in algorithmic baseline correction. Upon visual inspection, 24 spectra were identified as outliers due to poor quality or anomalies and were excluded from further analysis, resulting in a final dataset of 240 high-quality spectra. This preprocessing approach ensured the reliability and comparability of the dataset for subsequent analysis. R code is shown in Supplementary Table 3.

All analyses were performed using R version 4.0.5. Packages used include ggplot2 for data visualization, dplyr for data manipulation, ropls for OPLS-DA modeling, ggrepel for improved text labeling in plots, and gridExtra for arranging multiple plots.

Orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA)

OPLS-DA was employed to analyze the preprocessed Raman spectra due to its effectiveness in handling complex and high-dimensional data. OPLS-DA separates the predictive variation from the orthogonal variation, enhancing discrimination between classes. The full spectral range (200–3350 cm−1) was retained without band pre-selection or dimensionality reduction. The preprocessed spectra were used directly as input for the OPLS-DA model. One predictive component and six orthogonal components were used to capture relevant variations and remove irrelevant noise. Model performance was assessed using metrics such as the cumulative explained variation in the predictor variables (R2X(cum)), the cumulative explained variation in the response variable (R2Y(cum)), the predictive power (Q2Y(cum)), and the Root Mean Square Error of Estimation (RMSEE). Permutation testing confirmed the statistical significance of the model.

During the model development phase, different numbers of orthogonal components were tested to evaluate their impact on the cumulative explained variation in the predictor variables (R2X) and the response variable (R2Y), as well as the predictive accuracy (Q2Y)—exclusion of regions below 200 cm−1 and above 2400 cm−1 further improved model robustness. The model performance metrics showed a plateau in R2Y and Q2Y values around five to six orthogonal components (Figure 4a). This plateau indicates that the optimal complexity of the model was achieved with six orthogonal components, effectively balancing the trade-off between capturing relevant variations and avoiding overfitting. The statistical significance of the OPLS-DA model was confirmed through permutation testing, a robust method used to validate the reliability of the model’s classification performance. In this testing, the response variable (biological sex) was randomly permuted 100 times to generate a distribution of R2Y and Q2Y values under the null hypothesis of no association between the predictors and the response. The results of the permutation test, with p-values of 0.01 for R2Y and Q2Y, confirming that the observed separation between male and female samples is statistically significant and not due to random chance, are shown in Figure 4b. R code is shown in Supplementary Table 4.

Identification of reliable discriminative features

We performed a detailed analysis of the OPLS-DA model to identify reliable discriminative features. The predictive loadings, which indicate the contribution of each wavenumber to the discriminative model, were extracted from the OPLS-DA model. Additionally, orthogonal loadings for the six orthogonal components, which represent variations orthogonal to the predictive component, were also extracted. The six orthogonal component loadings were then weighted by their respective explained variance. The explained variance of each orthogonal component indicates the proportion of variation captured by that component. By weighting the orthogonal loadings, we account for the relative importance of each component. These weighted orthogonal loadings were then summed to obtain the cumulative weighted orthogonal loadings. This cumulative measure reflects the combined influence of all orthogonal components. The predictive and cumulative weighted orthogonal loadings were normalized to a 0–1 scale to facilitate comparison (Figure 5a). This step ensures all loadings are on a common scale, making calculating and interpreting the subsequent indices easier. An index was calculated for each wavenumber to quantify its discriminative power, taking into account the potential noise introduced by orthogonal components. The index was computed as the absolute value of the normalized predictive loadings minus the absolute value of the cumulative weighted orthogonal loadings (Figure 5b). Wavenumbers with high index values were considered reliable features for sex determination, showing high predictive power and low influence from noise. Local maxima in the index values above a threshold of 0.25 were marked as reliable features, demonstrating strong predictive influence with minimal noise interference. This approach ensures that only wavenumbers with high predictive power but low orthogonal influence are highlighted as reliable features. R code is shown in Supplementary Table 5.

Deriving a simplified regression model for sex determination

To develop a practical tool for sex determination, we trained a logistic regression model using the identified peaks as predictors. The dataset was randomly split into a training set (70%) and a test set (30%) to evaluate the model’s performance. Significant peaks were identified based on their p-values (< 0.05) from the model summary. Of the initial ten peaks shown in Table 2, a refined logistic regression model, including only three significant peaks (373 cm−1, 1182 cm−1, and 1600 cm−1), was derived. The model’s performance was assessed using metrics such as the AUC, sensitivity, and specificity, and an ROC curve was plotted (Figure 6).

Data availability

The experimental data that support the findings of this study are available in Figshare with the identifier: https://figshare.com/s/a861c0d74dca745795d7.

Change history

28 May 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04229-4

References

Stewart, N. A., Gerlach, R. F., Gowland, R. L., Gron, K. J. & Montgomery, J. Sex determination of human remains from peptides in tooth enamel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 114, 13649–13654 (2017).

Nagare, S. P., Chaudhari, R. S., Birangane, R. S. & Parkarwar, P. C. Sex determination in forensic identification, a review. J. Forensic Dent. Sci. 10, 61–66 (2018).

Rogers, T. & Saunders, S. Accuracy of sex determination using morphological traits of the human pelvis. J. Forensic Sci. 39, 1047–1056 (1994).

Williams, B. A. & Rogers, T. Evaluating the accuracy and precision of cranial morphological traits for sex determination. J. Forensic Sci. 51, 729–735 (2006).

da Silva, J. C. et al. A systematic review of photogrammetry as a reliable methodology in gender identification of human skull. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 97, 102546 (2023).

Krishan, K. et al. A review of sex estimation techniques during examination of skeletal remains in forensic anthropology casework. Forensic Sci. Int. 261, 165e161–165e168 (2016).

Cavazzuti, C., Bresadola, B., d’Innocenzo, C., Interlando, S. & Sperduti, A. Towards a new osteometric method for sexing ancient cremated human remains. Analysis of late bronze age and Iron age samples from Italy with gendered grave goods. PLoS One. 14, e0209423 (2019).

Bewes, J., Low, A., Morphett, A., Pate, F. D. & Henneberg, M. Artificial intelligence for sex determination of skeletal remains: application of a deep learning artificial neural network to human skulls. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 62, 40–43 (2019).

Singh, S., Singha, B. & Kumar, S. Artificial intelligence in age and sex determination using maxillofacial radiographs: A systematic review. J. Forensic Odontostomatol. 42, 30–37 (2024).

Stone, A. C., Milner, G. R., Pääbo, S. & Stoneking, M. Sex determination of ancient human skeletons using DNA. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 99, 231–238 (1996).

Degrelle, S. A. & Fournier, T. Fetal-sex determination of human placental tissues. Placenta 61, 103–105 (2018).

Gokulakrishnan, P. et al. Determination of sex origin of meat and meat products on the DNA basis: a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 55, 1303–1314 (2015).

Devaney, S. A., Palomaki, G. E., Scott, J. A. & Bianchi, D. W. Noninvasive fetal sex determination using cell-free fetal DNA: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 306, 627–636 (2011).

Finch, J. L., Hope, R. M. & van Daal, A. Human sex determination using multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Sci. Justice. 36, 93–95 (1996).

Luptáková, L. et al. Sex determination of early medieval individuals through nested PCR using a new primer set in the SRY gene. Forensic Sci. Int. 207, 1–5 (2011).

Rohland, N. & Hofreiter, M. Ancient DNA extraction from bones and teeth. Nat. Protoc. 2, 1756–1762 (2007).

Pretty, I. A. & Sweet, D. A look at forensic dentistry–Part 1: the role of teeth in the determination of human identity. Br. Dent. J. 190, 359–366 (2001).

Sweet, D. & DiZinno, J. A. Personal identification through dental evidence–tooth fragments to DNA. J. Calif. Dent. Assoc. 24, 35–42 (1996).

Suman, P., Manju, R., Shetty, V. A., Hegde, A. M. & Muthtamil, Rao, S. Sex determination from the pulp tissue of deciduous teeth exposed to natural soil and wet clay - A PCR study. Indian J. Dent. Res. 31, 562–568 (2020).

Sasaki, S. & Shimokawa, H. The amelogenin gene. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 39, 127–133 (1995).

Lau, E. C., Mohandas, T. K., Shapiro, L. J., Slavkin, H. C. & Snead, M. L. Human and mouse amelogenin gene loci are on the sex chromosomes. Genomics 4, 162–168 (1989).

Sullivan, K. M., Mannucci, A., Kimpton, C. P. & Gill, P. A rapid and quantitative DNA sex test: fluorescence-based PCR analysis of X-Y homologous gene amelogenin. Biotechniques 15, 636–638 (1993). 640 – 631.

Chowdhury, R. M. et al. Sex determination by amplification of amelogenin gene from dental pulp tissue by polymerase chain reaction. Indian J. Dent. Res. 29, 470–476 (2018).

Álvarez-Sandoval, B. A., Manzanilla, L. R. & Montiel, R. Sex determination in highly fragmented human DNA by high-resolution melting (HRM) analysis. PLoS One. 9, e104629 (2014).

Fujimoto, K. et al. Highly sensitive sex determination method using the exon 1 region of the amelogenin gene. Leg. Med. (Tokyo). 59, 102136 (2022).

Mikšík, I., Morvan, M. & Brůžek, J. Peptide analysis of tooth enamel—A sex estimation tool for archaeological, anthropological, or forensic research. J. Sep. Sci. 46, e2300183 (2023).

Gowland, R. et al. Sex estimation of teeth at different developmental stages using dimorphic enamel peptide analysis. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 174, 859–869 (2021).

Quincey, D., Carle, G., Alunni, V. & Quatrehomme, G. Difficulties of sex determination from forensic bone degraded DNA: A comparison of three methods. Sci. Justice. 53, 253–260 (2013).

Demarchi, B. et al. Protein sequences bound to mineral surfaces persist into deep time. eLife 5, e17092 (2016).

Gamble, J. A. et al. Advancing sex estimation from amelogenin: applications to archaeological, deciduous, and fragmentary dental enamel. J. Archaeol. Sci.-Rep. 54, (2024).

Brůžek, J. et al. Undertaking the biological sex assessment of human remains: the applicability of minimally-invasive methods for proteomic sex estimation from enamel peptides. J. Cult. Herit. 66, 204–214 (2024).

Buonasera, T. et al. A comparison of proteomic, genomic, and osteological methods of archaeological sex estimation. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-68550-w.

Ziganshin, R. H., Berezina, N. Y., Alexandrov, P. L., Ryabinin, V. V. & Buzhilova, A. P. Optimization of method for human sex determination using peptidome analysis of teeth enamel from teeth of different biological generation, archeological age, and degrees of taphonomic preservation. Biochem. (Mosc). 85, 614–622 (2020).

Butler, H. J. et al. Using Raman spectroscopy to characterize biological materials. Nat. Protoc. 11, 664–687 (2016).

Song, J., So, P. T. C., Yoo, H. & Kang, J. W. Swept-source Raman spectroscopy of chemical and biological materials. J. Biomed. Opt. 29, S22703 (2024).

Kuhar, N., Sil, S., Verma, T. & Umapathy, S. Challenges in application of Raman spectroscopy to biology and materials. RSC Adv. 8, 25888–25908 (2018).

Raman, C. V. & Krishnan, K. S. A new type of secondary radiation. Nature 121, 501–502 (1928).

Lambert, P. J., Whitman, A. G., Dyson, O. F. & Akula, S. M. Raman spectroscopy: the gateway into tomorrow’s virology. Virol. J. 3, 51 (2006).

Salzer, R., Steiner, G., Mantsch, H. H., Mansfield, J. & Lewis, E. N. Infrared and Raman imaging of biological and biomimetic samples. Fresenius J. Anal. Chem. 366, 712–716 (2000).

Haka, A. S. et al. Diagnosing breast cancer by using Raman spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102, 12371–12376 (2005).

Allakhverdiev, E. S. et al. Raman spectroscopy and its modifications applied to biological and medical research. Cells. 11, (2022).

Galli, R. et al. Sexing of chicken eggs by fluorescence and Raman spectroscopy through the shell membrane. PLoS One. 13, e0192554 (2018).

Higgins, S., Jessup, R. & Kurouski, D. Raman spectroscopy enables highly accurate differentiation between young male and female hemp plants. Planta 255, 85 (2022).

Harz, M. et al. Minimal invasive gender determination of birds by means of UV-resonance Raman spectroscopy. Anal. Chem. 80, 1080–1086 (2008).

Muro, C. K., de Souza Fernandes, L. & Lednev, I. K. Sex determination based on Raman spectroscopy of saliva traces for forensic purposes. Anal. Chem. 88, 12489–12493 (2016).

Banjšak, L., Gamulin, O. & Birimiša, M. Age estimation and sex determination using Raman spectra of human dentine. Acta Stomatol. Croat. 57, 353–363 (2023).

Gamulin, O. et al. Possibility of human gender recognition using Raman spectra of teeth. Molecules. 26, (2021).

Sikirzhytskaya, A., Sikirzhytski, V. & Lednev, I. K. Determining gender by Raman spectroscopy of a bloodstain. Anal. Chem. 89, 1486–1492 (2017).

Smith, G. D. & Clark, R. J. H. Raman microscopy in archaeological science. J. Archaeol. Sci. 31, 1137–1160 (2004).

Williams, A. C., Edwards, H. G. & Barry, B. W. The ‘iceman’: molecular structure of 5200-year-old skin characterised by Raman spectroscopy and electron microscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1246, 98–105 (1995).

Edwards, H. G. et al. Raman spectroscopy of Natron: shedding light on ancient Egyptian mummification. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 388, 683–689 (2007).

Robinson, C., Brookes, S. J., Shore, R. C. & Kirkham, J. The developing enamel matrix: nature and function. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 106 (Suppl 1), 282–291 (1998).

Simmer, J. P. & Hu, J. C. Expression, structure, and function of enamel proteinases. Connect. Tissue Res. 43, 441–449 (2002).

Ramakrishnaiah, R. et al. Applications of Raman spectroscopy in dentistry: analysis of tooth structure. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 50, 332–350 (2015).

Dozenist Radiograph of lower right 3rd, 2nd, and 1st molars in an 11-year-old child [image]. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Molarsindevelopment11-24-05.jpg (2005).

Pathologist without a beard. Tooth enamel under microscope [image]. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tooth_Smile.jpg (2021).

Shah, F. A. High-resolution Raman spectroscopy reveals compositional differences between pigmented incisor enamel and unpigmented molar enamel in Rattus norvegicus. Sci. Rep. 13, 12301 (2023).

Cuy, J. L., Mann, A. B., Livi, K. J., Teaford, M. F. & Weihs, T. P. Nanoindentation mapping of the mechanical properties of human molar tooth enamel. Arch. Oral Biol. 47, 281–291 (2002).

Kirchner, M. T., Edwards, H. G. M., Lucy, D. & Pollard, A. M. Ancient and modern specimens of human teeth: A fourier transform Raman spectroscopic study. J. Raman Spectrosc. 28, 171–178 (1997).

WentrupByrne, E., Armstrong, C. A., Armstrong, R. S. & Collins, B. M. Fourier transform Raman microscopic mapping of the molecular components in a human tooth. J. Raman Spectrosc. 28, 151–158 (1997).

Shah, F. A. Towards refining Raman spectroscopy-based assessment of bone composition. Sci. Rep.-Uk 10, (2020).

Chalmers, J. M. & Griffiths, P. R. Handbook of Vibrational Spectroscopy (2002).

Nemecek, D., Stepanek, J. & Thomas, G. J. Jr. Raman spectroscopy of proteins and nucleoproteins. Curr. Protoc. Protein Sci. Chap. 17, Unit17.18 (2013).

Diem, M., Griffiths, P. R. & Chalmers, J. M. Vibrational Spectroscopy for Medical Diagnosis. (Wiley, 2008).

Morgan, A. A., Rubenstein, E. & Proline The distribution, frequency, positioning, and common functional roles of proline and polyproline sequences in the human proteome. PLoS One 8, (2013).

Socrates, G. Infrared and Raman characteristic group frequencies: tables and charts. (2001).

Shimanouchi T, United States. National Bureau of S, United States.Dept. of C. Tables of molecular vibrational frequencies. NationalBureau of Standards; for sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. Govt.Print. Off. (1972).

Nelson, D. G. A. & Williamson, B. E. Low-temperature laser Raman-spectroscopy of synthetic carbonated apatites and dental enamel. Aust J. Chem. 35, 715–727 (1982).

Ager, J. W., Nalla, R. K., Breeden, K. L. & Ritchie, R. O. Deep-ultraviolet Raman spectroscopy study of the effect of aging on human cortical bone. J. Biomed. Opt. 10, (2005).

Anwar Alebrahim, M., Krafft, C., Sekhaneh, W., Sigusch, B. & Popp, J. ATR-FTIR and Raman spectroscopy of primary and permanent teeth. Biomed. Spectrosc. Imaging. 3, 15–27 (2014).

Zhu, G. Y., Zhu, X., Fan, Q. & Wan, X. L. Raman spectra of amino acids and their aqueous solutions. Spectrochim. Acta A. 78, 1187–1195 (2011).

Osmani, A., Par, M., Škrabić, M., Vodanović, M. & Gamulin, O. Principal component regression for forensic age determination using the Raman spectra of teeth. Appl. Spectrosc. 74, 1473–1485 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the competitive IEM Starting Grant 2019 (01.01.2020–31.12.2021), which was awarded to P.E.E..

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.E.E. conceptualized the study. P.E.E. supervised the research. P.E.E. aquired funding for the research. R.H. and P.E.E. were involved in sample and/or data collection. F.J.R., P.E.E. and R.H. were involved in sample curation. R.H. undertook or assisted with lab work. P.E.E. and R.H. undertook formal analysis of the data. R.H., A.E.W., F.J.R., and P.E.E. were involved in writing, reviewing, and/or editing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article the legends of Figures 1,2,3 and 6 were incomplete. Due to a technical issue during the production of this Article, parts of the figure legends have been inadvertently truncated and erroneously stated elsewhere in the main text. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hug, R., Wood, A.E., Rühli, F.J. et al. Advancing non-destructive sex determination on human dental enamel using Raman spectroscopy. Sci Rep 15, 15519 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00407-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00407-6