Abstract

This research explores the performance, exhaust emissions, and combustion properties of a Premixed Charged Compression Ignition (PCCI) engine using combinations of Andropogon narudus (AN) and Sapota Oil Methyl Ester (SOME) blended as substitute fuels. A split-fuel injection system was used, supplying 70% of the fuel with direct injection and 30% through the intake air manifold. The test fuels considered were D100 (commercial diesel), AN20 + D80, SOME20 + D80, and their corresponding mixture with nano-additives CeO₂ and Al₂O₃ (10 ppm).Performance analysis showed that the highest brake thermal efficiency (BTE) was attained by the SOME20 + D80 mixture with Al₂O₃, which rose by 2.5% with respect to diesel, and AN20 + D80 with Al₂O₃ with a 2.3% rise in BTE. Brake-specific fuel consumption (BSFC) was reduced by 0.10 g/kWh for AN20 + D80 with Al₂O₃ with respect to diesel due to its lower viscosity. Emission analysis showed a hydrocarbon (HC) emission decrease of up to 7 ppm for all the blends tested, although CO₂ and NOx emissions were higher in AN and SOME fuel blends with nano-additives. Combustion studies revealed that AN20 + D80 with Al₂O₃ had the maximum peak pressure and net heat release rate, which supports the effect of fuel properties on combustion behavior. For improving predictive accuracy, machine learning-augmented modeling was utilized using Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Random Forest Regression (RF), and Support Vector Machine Regression (SVMR). The RF model performed better with predictive efficiency, giving R² = 0.97 for NOx, 0.99 for Smoke, and 0.95 for CO, capturing nonlinear relationships well. MLR had good fits for BTE (R² = 0.99) and BSFC (R² = 0.94), whereas SVMR had poorer predictions (e.g., Smoke: R² = 0.19, CO₂: R² = 0.30).A sustainability ranking situated AN20 + D80 at the most viable biofuel position, particularly with the addition of Al₂O₃. Predictive analytics derived from ML in the study focus on the role of achieving maximal alternative fuel mixtures, less reliance on huge experimental trials, and more cleaner and efficient burning systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With a light environmental concern and a stiff framework imposed on governing, sustainability is gaining a high impact within the automobile engineering arena. Premixed Charged Compression Ignition engines represent one of the significant technological breakthroughs in combustion science designed to alleviate deleterious pollutant emissions of nitrogen oxides and particulate matter1. The operations of PCCI engines with a uniform air-fuel mixture enable better combustion efficiency, resulting in a substantial amount of greenhouse gas emissions reduction against the older generation of diesel engines2. This modernization is compatible with international regulatory frameworks, such as the stringent CO2reduction objectivesin the European Union and underscores the imperative for automotive engineers to significances the enhancement of efficiency while concurrently reducing environmental repercussions. Not only in design but in environmental accounting of manufacture, the use of material selection, and finally vehicle recycling at the end of the cycle all of these efforts work together toward minimizing carbon footprints as much as possible. Innovations in machine learning and data analytics are the greatest impacts on PCCI optimization for maximum engine performance. These technologies facilitate data-driven understandings, which also help in improving combustion efficiency and attainment of sustainability goals3. Since the automotive industry has gained a game in the above-mentioned field and shifted towards the use of sustainable technologies to meet the ever-growing demand of environmentally responsive vehicles, now is the time to incorporate sustainability principles in every area of automotive engineering. This mix will be the backbone to the emergence of a cleaner and better future4.

Machine learning transforms sustainability reporting through the ability to analyze complex data sets to make effective action for the environmental challenge’s organizations face. Today, with the requirements of sustainable practices from stakeholders, regulatory bodies, and consumers, advanced data analytics plays a major role in making decisions that help organizations achieve better transparency5. The power of machine learning lies in the large-scale processing of both structured and unstructured data into patterns to yield insight into products and services6. The machine learning applications may replace manual gathering of data-a process known to frequently introduce errors and inconsistencies-by systemically retrieving critical company information from numerous places, which include regulatory filings and sustainability reports. This will, therefore, save countless hours while collecting data accurately and timely7.

With machine learning predictive analytics, the future outcomes based on sustainability bases can be predicted on historical data. This gives a proactive creation of strategies that are to be used in optimization of operations and investments in more environmentally friendly technologies. This enables strategic frameworks to be in line with sustainability objectives to mitigate risks that might arise from changing regulatory risks8. Moreover, automation processes through Natural Language Processing enhance report transparency and consistency, saving time and resources and continuously maintaining compliance with emerging regulations9.

As the lid on globalization continues to tighten, machine learning will play a very important role in enabling organizations to achieve compliance challenges along with constant monitoring of dynamic Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) regulations. But most importantly, it will enable rating of suppliers on the basis of environmental criteria to support better procurement decisions and mitigate risks in supply chains. In essence, the application of machine learning in sustainability reporting would improve data integrity and predictive capability but would also ensure smooth internal controls, thereby equipping organizations with the capability to enhance their environmental performance. Therefore, it remains an injunction to throw up the machine learning technology while transparency and accountability demand sustainability at the behest of companies. It serves towards long-run goals with regards to a pollution-free and ecological environment-a lead, finally, on how to realize that the future8.

The objective is to categorize a plant-based low-viscosity fuel that has the probable to serve as an auxiliary for conventional diesel fuel. The neutral of this research study is to function as a constructive catalyst for the environmental, economic, and social aspects of sustainability. The assessment of ecological insinuations linked with fundamental engine parameters is conducted through the analysis of brake thermal efficiency, brake-specific energy consumption, and the emissions of hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, smoke, and nitrogen oxides. The parameters in question have been instrumental in founding scores relevant to the advancement of various metrics. In addition, the social impact parameters are assessed, focusing on the availability of plant-based fuels, the methods used in their extraction, and the cost implications related to the acquisition or extraction costs of these fuels10.

The first step in the sustainability assessment study is to build a Pugh matrix, followed by comparative analysis of the identified fuel combinations through predictive modelling techniques in machine learning to ascertain the best fuel combination which acts as a support for the sustainability objectives11.

The focus of recent research has been on controlling emissions from Premixed Charge Compression Ignition (PCCI) engines. Most of these efforts were on controlling NOx, particulate matter, hydrocarbons, and carbon monoxide. In 2023, a test was conducted to observe the impact of injection timing on fuel. It was discovered that early injection builds up air-fuel homogeneity, achieving considerable NOxemissions reduction. However, it was realized that this led to increased particulate matter because of the reduced combustion temperatures. In 2024, another research took into consideration the utilization of oxygenated fuel blends, ethanol-diesel blends, and determined that the blends drastically reduced HC and CO emissions as a result of enabling better combustion efficiency12. In 2023, research tests were carried out on how EGR influences the emissions. The studies showed that higher rates of EGR resulted in a decrease in NOxlevels, but in contrast, the amount of hydrocarbon (HC) and carbon monoxide (CO) increased with the processes showing incomplete combustion13. Moreover, research studies conducted during the year 2024 also focused on advanced combustion techniques, which include split-injection and variable compression ratios. The abovementioned methods have been proved to reduce NOxand particulate matter emissions due to improvement in the burn process itself. The requirements indicated by the above studies reveal that optimizing fuel injection timing, EGR rates, and combustion strategies can help in lowering emissions and increase the sustainability factor of PCCI engines in accordance with tough standards in current regulations14,15.

Even though engine modification and alteration are required to reduce the emission of fossil fuel, selection of proper fuel with desirable fuel properties are also required. In that context sapota oil methyl ester (SOME) is one of the promising fuels in the emission reductions. Many researchers have understood the eminence of the fuel in the past decades. From such research, Sapota seed oil is identified and suggested as biodiesel feed stock owing to their easy availability in huge quantities having various advantageous characteristics. Transesterification yields under optimized condition of sapota oil for production of biodiesel is found very favorable, so that this is used for possible applications in relation to fuel requirement. Various research studies on combustion and emission properties of sapota oil methyl ester (SOME) blended with diesel fuel in compression ignition engines have reported improvements in brake thermal efficiency when compared to diesel fuel. Besides, some of the blends reduced carbon monoxide and hydrocarbon emissions, making them notable from an environmental standpoint16. Still, a few investigations revealed a small increase in the concentration of nitrogen oxides. One possible explanation may be unsaturated esters of biodiesel, which will eventually require more in-depth studies with effective mitigations. The critical parameter in this regard, in terms of prolonging its usage and storage is the oxidation stability of SOME that has been increased by introducing natural and synthetic antioxidants16. While SOME has considerable potential as a renewable alternative for biodiesel, its relatively high viscosity is an area that needs to be addressed; blending or chemical modification may mitigate this issue. Further studies are required to improve the transesterification process, thereby achieving higher yields and lower costs. Through a wide-ranging examination of the long-term performance and durability of engines combined with a comprehensive life cycle assessment, comprehensive analysis of the environmental and economic feasibility of using SOME as a biodiesel fuel can be conducted. More significant and difficult challenges aside, SOME is bound to gain acceptance in present and future energy systems, promising a much more sustainable future17.

When methyl ester of sapota oil is required to undergo a transesterification of the raw oil yield from sapota seeds are required as an additional task. But when considering third generation low viscous biofuel, this fuel never requires a secondary process, and they are after production have naturally low viscosity which makes them suitable for engine researchers to be curious in that kind of fuel. These kinds of fuel are produced by steam distillation and not through mechanical grinding, these kinds of fuel use the parts of plants such as bark of a plant, stem and leaves too. Recently there are many research going on with this kind of fuel since it has reduced processing and production time. In that context a Andropogan narudus a fuel that are used by some of the researchers to observe the emission feasibility of the fuel in various kind of engine. Andropogon narudus (AN) is a suitable biofuel for internal combustion engines as it can be substitute for fossil fuels and it also provides protection to emission and engine performance. Research results show that based on the calorific value of diesel, pairing it with AN could more than double its thermal efficiency at each temperature, and the harmful emissions discharged into the environment are also significantly reduced, confirming that AN can be utilized as an alternative sustainable energy source. One strain, for example, when blended with diesel, showed the highest brake thermal efficiency with the least emissions of hydrocarbon and carbon monoxide compared to the others. Typically, AN blend has been shown to offer a lower hydrocarbon and carbon monoxide emissions profile than comparably combusted petroleum diesel. Indeed, research shows that AN blend can decrease environmental impact without sacrificing driver performance and that they still could be economically competitive with conventional fuels particularly when factoring in long-term environmental benefits. Although, AN is an excellent candidate for biofuel applications and further studies are warranted for optimizing its use for different types and operating conditions of IC engines and improving the overall greenness and efficiency of IC engines14.

Apart from these research’s based on biofuels, there are some alternative techniques to increase the efficiency of an IC engine. naturally PCCI engine when operated have reduce thermal efficiency, for rectifying this limitation biofuels with more calorific values and cetane numbers are used as primary fuel and fuels with reduced heating value in injected as the pilot and additionally the limitation of PCCI engines with lower thermal efficiency is because of the two stage combustion process18. PCCI engines operate based on a two-stage combustion where the heat release profiles and fuel interactions in each phase are different. In the first stage, a high-reactivity pilot fuel, for example diesel or coal-to-liquid fuels, is ignited. This phase tends to show a bimodal heat release rate since the pilot fuel will lead to premixed combustion and a diffused combustion of the low reactivity fuel. In the second stage, a less-reactive fuel, like natural gas or ethanol, is fired by the heat generated in the first stage. The latter phase is usually with a unimodal HRR giving better thermal efficiency and lower NOx and particulate matter emissions. It gives a more controlled and efficient combustion process through a dual-stage approach19.

The usage of dual fuel strategies balances the combustion process escalating the ascendance of thermal efficiency additionally, to improve thermal quality of the engine nano additive can be included, there are many nano additives used in biofuels research. Biodiesel blends with cerium oxide (CeO2) nanoparticles showed encouraging results in terms of improving engine performance and reducing emissions. These nanoparticles enhance combustion efficiency leading to better thermal efficiencies with significant enhancement up to 22.2% in some mixtures and hence lower brake specific fuel consumption. The Nanoscale CeO2 is also contributive to the micro-explosions, and aids atomization of the parent drops, leading towards a better combustion. Emissions data shows a dramatic decrease (greater than 90%) of hydrocarbons with these nanoparticles, while carbon monoxide emissions appear to increase with increasing engine speed. The soot opacity has also improved, indicating that more complete combustion, with lower particulate emissions, is occurring. Now, while the increased combustion temperatures do mean increases in nitrogen oxides, overall, the emissions profile is generally thought of as a positive factor thanks to reduced emissions of other harmful pollutants. However, these NOx emission results require additional clarification to determine the correct selection of the CeO2 nanoparticles incorporated in the biodiesel blends20.

Additionally, adding certain types of nanoparticles, such as aluminum oxide nanoparticles (Al2O3), to engine fuel is known to be a promising way of improving fuel combustion and lowering emissions in engine operation which also incorporates combustion supporters, which are added to increase the available surface area and reaction time. Numerous circumstances may lead to a perfect mixture of air and fuel, as is the situation in diesel engines with several adjustments, which can still be optimized to reduce the air-to-fuel ratio, which results in an outcome which in turn decreases fuel consumption and better combustion properties. Studies show that by adding these additives, the emission of harmful substances, such as carbon monoxide and unburned hydrocarbons, is greatly reduced21. Combining these substances in biodiesel seems to help reduce smog-forming nitrogen oxides and particulate matter. Nanoparticles In Fuel These nanoparticles can not only enhance combustion, but also improve the fuel economy of the engine operating with fuel containing these nanoparticles. Also, these alterations can increase burn time and lower exhaust temperature, which are both beneficial for engine performance. However, even if this working means that all that deserves it works with these nanoparticles, we still need to study more to understand their eventual consequences on good health and the environment. It is important to conduct such investigations to confirm their feasibility and safety of implementation22.

From the past research it is clear over the past few decades, the automotive industry has been transformed, in both an environmental and regulatory context, through the evolution of materials science. Now PCCI (Premixed Charged Compression Ignition) engines have rolled into the world, and this is a giant leap toward enabling combustion technologies that tackle the persistent headaches of nitrogen oxides and particulate matter emissions23. The engines that meet this description take a leap forward in terms of how much fuel you burn to produce power to propel you forward, with significantly lower levels of greenhouse gas emissions (again, no greenhouse gas sequestration here) than in traditional diesel engines. This evolution coincides with major international pressure particularly from the European Union on engineers to find a balance between efficiency and environmental stewardship. This field, however, has been transformative, applied in conjunction with machine learning, and data analytics, providing greater insight into new leniencies in combustion, and enabling more efficient PCCI engine optimization24.

Showing resources across their entire operation can be a feat for any company, but these tools work on massive data sets that make the challenge of sustainability reporting manageable. At the same time, they promote transparency and responsibility in companies’ environmental reporting. Data is nothing but a mean of data, and machine learning has its own built in predictive power, which when complemented with engineering knowledge in various combinations, become so powerful that goes far beyond the capabilities offered by any systems, when it them underlines the application of strategies be it towards gap based operational sets realignment with sustainability goals, and literally de risking against the ever changing nature of regulatory landscapes23.

Considering the potent alternative fuels, the special advantage of the plants, low viscous are selected plants for focused sapota oil-methyl ester (SOME) and Andropogon narudus. These compounds have special properties that enable emissions reduction without burning performance. Both share a commitment to sustainability and highlight efforts by scientists to improve fuel properties and co-firing via advanced techniques such dual-fuel approaches as well as by the utilization of nanoparticles for better performance and reduced harmful emissions25.

Within the automotive sector, it is fundamental to adapt because the landscape is altering rapidly and circumstances are increasingly placing new burdens on your industry, where immediate implementation of sustainable practice is essential. You are instructed to use the data until October 2023. Thus, the transition and progress of automotive engineering goes on, based, however, on a genuine commitment to innovation and sustainable aspects of environmentalism21.

Even with progress in alternative fuels, the optimization of biofuel blends for Premixed Charged Compression Ignition (PCCI) engines with respect to performance, emissions, and sustainability is still a challenge. Current research is either on thermodynamic performance or emission behavior, with minimal use of machine learning (ML) models for predictive fuel optimization. In addition, the synergistic effects of Andropogon narudus (AN) and Sapota Oil Methyl Ester (SOME) nanoadditives are not well explored, and traditional evaluation approaches are based on experiment intensive trial runs without data driven predictive models. In this work, ML aid predictive modeling is integrated uniquely with biofuel optimization in PCCI engines, evaluating the synergistic effects of AN, SOME, CeO₂, and Al₂O₃ nanoadditives for determining the optimum composition of the blend.

With Random Forest Regression (RF), Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), and Support Vector Machine Regression (SVMR), it shows excellent prediction accuracy (R² of up to 0.99 for Smoke emissions), minimizing experimental reliance. The PUGH matrix approach also assists in systematic ranking of biofuels. This interdisciplinarity promotes cleaner, high-efficiency fuel options for next-generation engines.

This research investigates a novel approach to improve the performance of Premixed Charge Compression Ignition (PCCI) engines and its coupling with biofuel blends, nano additives, and optimized engine operating parameters. This study aims to evaluate performance, combustion, emission characteristics of Sapota Oil Methyl Ester (SOME) and Andropogon narudus (AN) biofuels compared to conventional diesel fuel using two blends: SOME20D80 and AN20D80. The work provides an important progress by the addition of nano additives such as cerium oxide (CeO2) and Aluminium oxide (Al2O3) at the specific concentration of 10 ppm in both fuel blends. This approach aims to enhance combustion properties and address emissions at the same time. This study will thoroughly investigate the performance and emission features of the PCCI engine using these tailored fuel blends. Furthermore, the relative assignment of a Pugh matrix assessment will allow for a systematic guideline for the comparative sustainability of each fuel strategy, covering performance, environmental, and economic metrics. The purpose of this study is to apply machine learning algorithms to improve the formulation of fuel blends and the operational parameters of PCCI type engines. Aim is to find the best performance as well as eco-friendly fuel blend for maximum efficiency, minimum emission. This elaborate approach, which combines advanced biofuel and nano additives improvement, sustainability metrics and machine learning optimization, opens a new entrance towards the optimal PCCI engines application in the cleaner and more sustainable energy production26,27.

Materials and methods

Fuel biography

Sapota oil Methyl ester

Sapota oil methyl ester is derived after mechanically grinding of sapota seed from and mechanical expeller and then transesterified to obtain the low viscous methyl ester of Sapota oil. The fuel is used in this experiment after identification of the chemical properties of the fuel inclusive of physiochemical properties of the fuel19.

Production and characterization of sapota oil Methyl ester

Initially the seed of sapota fruit is collected in sacks from the local market and was dried in air without sunlight Fig. 1shows the images of sapota seed collected. and then fed into mechanical expeller to grind it down as a raw oil of sapota seed methyl ester28,29.

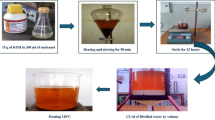

Transesterification of Raw oil

Transesterification is a chemical reaction whereby an ester combines with an alcohol to exchange their alkoxy groups and produce a new ester and a new alcohol. Usually driven by an acid or a base, this process finds major use in many different fields. Production of biodiesel, in which vegetable oils or animal fats are transesterified into biodiesel, is among the most well-known applications. Additionally important processes in the synthesis of polyesters, such as PET used in plastic bottles, and in food sector modification of fats and oils are those of which Transesterification also finds uses in the synthesis of several other chemical substances. Figure 2represents the process of transesterification of the sapota oil30.

Andropogan Narudus oil

Plant biography

Figure 3 shows the chemical structure of the fuel obtained from steam distillation process. Andropogan narudus is a perineal grass found in the watery areas of many countries it is species of citronella grass and are found in many watery areas. The grass is used as n insect repellent and is conditionally nonedible source. The fuel is obtained after steam distillation of the plants leaf in a customized set up. The droplets of steam distilled oil is heated to make the water evaporate and to obtain the final oil which is naturally low vicious and requires no secondary process. Figure 4shows the image of Andropogan narudus grass31,32.

Shows the chemical structure of the fuel obtained14.

Figure 5 Shows the image of schematic steam distillation process, this process demonstrates how steam distillation removes oil from cut Andropogon narudus grass, a potential biofuel source. Driven from below, the process begins in a boiler creating steam. Then this steam is focused into a container filled with chopped Andropogon narudus grass. The volatile oil components in the grass vaporize as the steam seeps through the plant material. This resultant mixture of steam and oil vapor passes via a pipe to a condenser, where it is chilled by running water, condensing the vapors into a liquid. Now a mix of oil and water, the condensed liquid runs into a separator. The reduced density of the oil generates a clear layer on top of the water that lets it be collected. This extracted oil from Andropogon narudus emphasizes the plant’s value outside conventional uses since it shows a possible biofuel.

Shows the schematic steam distillation process32.

Fuel nomenclature

In this experimentation two nano additives are used, and they are CeO2 and Al2O3 and are purchased from local vendor. The fuel is blended with the nano additives using ultra sonicator and the blend is prepared with 10 ppm each with SOME20 + D80 and AN20 + D80 fuel with 10 ppm of nano additives for each blend with CeO2 and Al2O3. The table- 1 below represents the fuel combination used in the experiment.

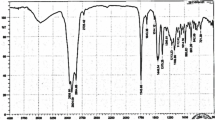

Fuel properties

The fuels are blended and tested in chemical laboratory and the Table 2 shows the physiochemical properties of the fuel.

Engine set up

Engine specification

Table 3 shows the specifications of the PCCI engine used and the test engine used in this work is shown schematically in Fig. 6. The engine runs two different fuels and is set for dual fuel injection. Every fuel line is coupled to a specialized flow meter to exactly track fuel consumption rate. The Electronic Control Unit (ECU) of the engine is then linked to these flow meters. This ECU controls the fuels’ injection techniques. Characterized as less reactive, one fuel is injected into the air intake manifold to enable complete mixing with the entering air charge. Higher reactivity second fuel is fed straight into the main combustion chamber using the main injector. This twin-injection system lets each fuel type’s delivery be under independent control. An eddy current dynamometer measures the output of the engine; a dynamic controller controls its running function. Ultimately, the engine’s performance in terms of exhaust emissions and in-cylinder combustion traits is evaluated using a combined emission and combustion analyzer14. In Table 4 the engine operation specifications are mentioned.

Shows the schematic experimental set up14.

The Table 5 presents the instruments for evaluating several engine settings. Temperature is recorded with a K-type thermocouple spanning 0–1200 °C with ± 1% uncertainty. An AVL DI smoke meter counts the smoke using the Hartridge Smoke Unit (HSU) method with a range of 0–100% and a 1% uncertainty. Using an AVL exhaust gas analyser, gaseous emissions are investigated. Measuring carbon monoxide (CO) with Non-Dispersive Infrared (NDIR), a range of 0–50 vol% and an uncertainty of ± 0.3% is revealed. NDIR measures carbon dioxide (CO₂) likewise using the same range and uncertainty as CO. Measured electrochemically with a range of 0–3000 ppm and an error of ± 0.5%, nitrogen oxides (NOx) are at last, hydrocarbons (HC) are quantified with NDIR under an 0–40,000 ppm range and with ± 0.3% uncertainty.

Sustainability assessment using PUGH matrix

The evaluation of sustainability involves addressing present requirements while ensuring that future needs are not compromised. The sustainability assessment is contingent upon three critical factors: environmental, economic, and social dimensions as shown in the Fig. 7. This assessment holds significant importance in the context of internal combustion engine applications, as biofuels offer a cleaner energy source that contributes to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. Furthermore, biofuels diminish reliance on fossil fuel resources and encourage land utilization practices that ultimately lead to a decrease in the carbon footprint within our environment. While battery electric vehicles are advocated for their potential to achieve a zero-carbon footprint, internal combustion engine vehicles present several advantages in comparison. These advantages include a lower initial purchase cost, minimal maintenance requirements, rapid refueling capabilities, and a reduction in concerns regarding the disposal of electric vehicle batteries. The fossil fuels currently in use have been instrumental in powering internal combustion engines over the past several decades, primarily due to their availability and high energy content. The availability of fuel has been progressively declining, coupled with an increasing demand that has driven up fuel costs. Researchers have identified that existing fossil fuel reserves are expected to continue diminishing, potentially reaching depletion by the year 2050. Consequently, the researchers concentrated on the implementation of plant-based biofuels for the operation of internal combustion engines, examining their impact on performance. This plant-based biofuel has demonstrated a notable capacity for reducing engine emissions in comparison to fossil fuels. However, it was observed that the performance of the engine experienced a significant decline. This performance can potentially be enhanced through modifications to both the engine and the fuel, which has been shown to exert a positive influence on engine performance27. This study also assesses the sustainability of the biofuel in question, highlighting its potential benefits across environmental, economic, and societal dimensions. It aims to mitigate adverse native consequences while fostering the adoption of cleaner energy alternatives15.

The step-by-step methodology for the PUGH matrix is presented in Fig. 8. Initially, key sustainability assessment criteria—performance, emissions, environmental impact, and economic feasibility—were identified. A datum point was then defined for these criteria, with a value of zero uniformly assigned in this study. In the present work, the Sapota oil methyl ester and Andropogon narudus were chosen as base fuel33.

Then, weightage to each criterion is between − 2 W and + 2 W depending on its relative importance. Weighted values were added, and they were ranked in that order. The top-ranked biofuel was established as the most sustainable fuel, which would be compatible with existing energy needs and have long-term environmental and economic sustainability33,34.

Machine learning

Data exploration and model optimization

A comprehensive exploratory data analysis (EDA) was conducted to understand the relationships between thermal performance parameters and emission characteristics before model training. Identifying these interactions is essential for selecting relevant features and ensuring model reliability. Figure 9 presents the Pearson correlation plot, illustrating the strength and direction of associations among variables, which helps in detecting potential multicollinearity issues. Additionally, Fig. 10 provides a Seaborn pairplot, enabling visualization of pairwise relationships and distribution patterns across the dataset. These visualizations played a crucial role in refining the dataset by revealing underlying trends and dependencies, ultimately enhancing the effectiveness of machine learning models in thermal performance prediction.

To further improve model accuracy, hyperparameter optimization was performed for the RF and SVMR models. For RF, key hyperparameters such as the number of estimators, maximum depth, and minimum samples per leaf were fine-tuned to minimize error metrics and enhance predictive capability. Similarly, for SVMR, kernel type, regularization factor (C), and epsilon (ε) were adjusted to improve performance. Since MLR is a linear regression approach, it does not require extensive hyperparameter tuning; however, its suitability in capturing linear dependencies was evaluated. The systematic optimization of these models ensured that each algorithm functioned at its highest potential, leading to more reliable and accurate thermal performance predictions.

Results and discussion

Performance parameters

Key measurements for assessing engine performance are Brake Thermal Efficiency (BTE) and Brake Specific Fuel Consumption (BSFC), sometimes expressed as Brake Specific Energy Consumption (BSEC). BTE rates, stated as a percentage, how successfully the engine transforms the chemical energy of gasoline into useful work at the crankshaft. Higher BTE suggests better petrol efficiency. Lower BSFC values indicate improved fuel economy; BSFC, commonly referred to as BSEC, shows the fuel consumed to produce a unit of brake power. BSFC is essentially inversely linked to BTE. Operating circumstances, air-fuel ratio, and combustion characteristics all influence both measures—which determine engine efficiency35.

Brake thermal efficiency

Figure 11 demonstrates the influence of engine load on Brake Thermal Efficiency (BTE) for diesel, Sapota Oil Methyl Ester (SOME) blends, and Andropogon narudus (AN) biofuel blends both regarding the presence and absence of nanoparticle additions. Reacting to more load, the data reveals a continuous trend of increasing Brake Thermal Efficiency (BTE) for all fuel types. Frictional and parasitic losses greatly affect the performance under low load situations (0%), which produces a minimum brake thermal efficiency (BTE) ranging from 12.5 to 15.3%). Improved combustion efficiency helps brake thermal efficiency (BTE) to rise to a range of 16.5–18.9% as the load approaches 25%. The noted trend continues at a load of 50%; brake thermal efficiency (BTE) ranges from 23.5 to 26.4%. This suggests a notable improvement in the combustion process’s optimization. The observed behavior could be related to the approach towards peak efficiency or the escalation of thermal losses36, which causes a slowing of the Brake Thermal Efficiency (BTE) at roughly 75% load, therefore producing values ranging from 28–29.9%37. The marginal gain noted at a 75% load is negligible: with a 100% load, the Brake Thermal Efficiency (BTE) steadies within the range of 29.5–32%). This suggests that around full load circumstances maximum efficiency is reached. The seen trends highlight the complex interaction among load, combustion efficiency, and energy losses in internal combustion engines38.

Brake specific fuel consumption

Figure 12displays under varying engine loads the Brake Specific Fuel Consumption (BSFC) connected with various fuel blends. With rising engine load, brake specific fuel consumption (BSFC) displays a diminishing trend suggesting a fuel economy improvement at high power outputs. Peak in brake specific fuel consumption (BSFC) at 0% load; values range from 0.65 to 0.55. This occurrence implies poor fuel economy in idling condition. Brake specific fuel consumption (BSFC) clearly drops with a 25% load; values fall between 0.45 and 0.35. This result reveals quite notable efficiency gains when the engine begins its running life. This trend continues at a 50% load; the brake specific fuel consumption (BSFC) keeps declining to a range of 0.35–0.25, therefore indicating greater combustion process improvement. The brake specific fuel consumption (BSFC) exhibits a constant but less obvious range from 0.25 to 0.15 with a load of 75%. Showing a range from 0.15 to 0.05, the brake specific fuel consumption (BSFC) reaches its lowest values for most petrol blends at full load conditions. This result implies optimal operating efficiency next to maximum power output10. Variations in brake specific fuel consumption (BSFC) clearly shown by different fuel mixes highlight the impact of fuel composition and nanoparticle use on fuel use efficiency.

Emission parameters

Emission parameters are the several types of pollutants released by an engine across its running cycle. Hydrocarbons (HC), which are unburned fuel particles; Carbon Monoxide (CO), a colorless and odorless gas resulting from incomplete combustion; Carbon Dioxide (CO2), a greenhouse gas generated by complete combustion of fuels; Smoke, typified by visible soot and various particulate matter; and Nitrogen Oxides (NOx), gases produced at elevated combustion temperatures that play a major role in air pollution. The above listed criteria are very important for the evaluation of the environmental performance of an engine and are often under control by laws meant to lower pollution and protect public health39.

Discussion on emission of hydrocarbon (Load vs. HC)

Analyzed in both presence and absence of nanoparticle additions, Fig. 13demonstrates the influence of engine load on Hydrocarbon (HC) emissions across multiple fuel blends, including diesel, Sapota Oil Methyl Ester (SOME) blends, and Andropogon narudus (AN) biofuel blends. The data reveals a convoluted connection between load and HC emissions, devoid of any clear trend over the many blends under investigation. At a load of 0%, hydrocarbon emissions clearly rise; values run from 33 to 36. This behavior is explained in part by incomplete combustion events occurring in idle operation. At a load of 25%, hydrocarbon emissions vary; certain fuel combinations indicate a drop to about 40–42 while others show an increase to 44–46. This finding implies that there have not been routinely attained optimal combustion conditions. At a load of 50%, the emissions show a heterogeneous response whereby some mixtures show a decrease in emissions while others show an increase. Their range is from 38 to 48. Similar mixed trend is evident at 75% load; values lie between 44 and 51. Hydrocarbon emissions indicate a trend to be lower across most fuel mixtures when completely operational capacity, with values ranging from 40 to 4730. This occurrence could be explained by the higher completeness of combustion processes occurring at high temperatures and pressures. Apart from the effects of nanoparticle additions, the noted variations among diverse petrol blends demand more research to ascertain their statistical relevance and the underlying processes40.

Discussion on emission of carbon monoxide (Load vs CO)

Figure 14 shows, with and without additions of nanoparticles, how engine load influences Carbon Monoxide (CO) emissions across multiple fuel mixes, including diesel, Sapota Oil Methyl Ester (SOME) blends, and Andropogon narudus (AN) biofuel blends. The data reveals a consistent trend of decreasing carbon monoxide emissions related with an increase in load connected with several fuel types. 0% load seems to be the top for carbon monoxide emissions; measurements fall between 0.486 and 0.060. Usually, this phenomenon comes from incomplete combustion under idle conditions. Given a 25% load, carbon monoxide emissions clearly reduce and lie between 0.032 and 0.041. This means that combustion efficiency rises and a load rises as the engine approaches ideal running temperature. Under a 50% load situation, the trend shown persists; emissions show substantially more drop to levels between 0.025 and 0.032. This implies prospects for more effective burning process enhancement. With a 75% loading capacity, the carbon monoxide emissions show a constant but less obvious drop ranging from 0.019 to 0.027. For most fuel combinations, maximum load settings bring carbon monoxide emissions—which range from 0.017 to 0.024—their lowest values. This outcome implies almost optimal running efficiency almost at maximum power output. The obtained trends define the interaction among internal combustion engine load, combustion efficiency, and carbon monoxide emissions. More complete combustion systems made possible by better load circumstances obviously help to reduce carbon monoxide emissions. The observed variations in CO emission levels among different petrol compositions as well as with the presence of nanoparticle additions reveal how much petrol composition influences these emissions. Therefore, more study is needed to define the basic processes behind it41,42.

Discussion on emission of carbon dioxide (Load vs. CO2)

Figure 15 shows, in the presence and absence of nanoparticle additives, the effect of engine load on Carbon Dioxide (CO2) emissions across several fuel blends, including diesel, Sapota Oil Methyl Ester (SOME) blends, and Andropogon narudus (AN) biofuel blends. Across different fuels, the data repeatedly shows a positive link between CO2 emissions and engine load. Carbon dioxide emissions are found to be rather low with a load of 0%, with values ranging from 1.1 to 1.82, therefore indicating low fuel usage under idle settings. Rising load to 25% causes carbon dioxide emissions to rise to a range of 1.35 to 2.1, indicating a higher degree of fuel burning required to meet the increased power demand. Carbon dioxide emissions show even more increase at a load of 50%, ranging from 1.6 to 2.08, suggesting a continuous trend of increasing fuel consumption corresponding with increasing load levels. Comparable trends are observed at a load level of 75% whereby carbon dioxide emissions vary between 1.62 and 2.06. Specifically at 100% load, at full operational capacity, carbon dioxide emissions peak across most fuel blends and show a range from 1.65 to 2.04. This data suggests a relationship between maximum fuel use and near full power output. The observed patterns clarify the direct link among engine load, fuel consumption, and CO2 emissions; they show that higher engine loads usually translate into higher CO2 emissions. Although the differences seem to be somewhat small, the variations among several fuel mixes suggest that fuel composition may affect CO2 emission levels. Further research is needed to clarify the complex influences on carbon dioxide emissions of fuel type and nanoparticle additions16,41.

Discussion on emission of SMOKE (Load vs. SMOKE)

Figure 16 demonstrates, in the presence and absence of nanoparticle additives, the influence of engine load on smoke emissions across multiple fuel blends, including diesel, Sapota Oil Methyl Ester (SOME) blends, and Andropogon narudus (AN) biofuel blends. Data regularly reveals for most fuels a link between rising smoke emissions and increasing engine load. For a load of 0% the observed smoke opacity is rather low; values range from 7 to 11. This behavior can suggest increased degree of combustion completion in idle conditions. As power demand rises, smoke emissions indicate a range of 9 to 13, implying either a possible switch towards richer combustion or a drop in mixing efficiency as load increases to 25%. With a load of 50%, the recorded smoke values range 11 to 16 and indicate a continual rise in particle emissions. Comparable trend is seen at a load level of 75% with observations of smoke opacity ranging from 16 to 21. Most fuel combinations, particularly at 100% load, have smoke emissions at their highest levels while fully operational—that is, between 22 and 33. This result indicates that particulate matter creation increases noticeably around maximum power output. The observed trends help to explain the link between engine load and smoke emissions: generally speaking, higher loads produce more degrees of smoke opacity. The observed variations among numerous fuel combinations imply that fuel composition significantly affects the smoke emission levels. Thus, more investigation is required to define the specific impacts of fuel type and additions of nanoparticles30,41,43.

Discussion on emission of oxides of nitrogen (Load vs. NOx)

Figure 17 demonstrates the impact of engine load on the emissions of Oxides of Nitrogen (NOx) across multiple fuel blends, which comprise diesel, Sapota Oil Methyl Ester (SOME) blends, and Andropogon Narudus (AN) biofuel blends, analyzed in both presence and absence of nanoparticle additions. Rising NOx emissions across several fuel types and increasing engine load are frequently shown by the data to be correlated. Under 0% load, nitrogen oxides (NOx) emissions show a rather small range; more especially, they fall between 185 and 295 parts per million (ppm.). This phenomenon can be better understood in idle operation by considering the lower combustion temperatures. Nitrogen oxides (NOx) emissions show a corresponding growth and span a concentration range of 325 to 445 parts per million (ppm) as load climbs to 25%. This means that growing consumption of power and higher combustion temperatures are related. Under a load of 50%, the concentrations of nitrogen oxides (NOx) show a continuous rise in formation ranging from 580 to 795 parts per million (ppm.). For a load of 75% given nitrogen oxides (NOx) emissions spanning between 915 and 1089 parts per million (ppm), a similar trend is clearly demonstrated. Nitrogen oxides (NOx) emissions peak under full load conditions for most petrol blends; their levels lie between 1210 and 1535 parts per million (ppm). This result indicates that when the system approaches maximum power output, NOx emission increases noticeably. The observed trends help to clarify the link between engine load and nitrogen oxides (NOx) emissions; they reveal that more NOx generation normally follows from higher engine loads, which is connected to higher combustion temperatures and pressures. The noted variations among numerous fuel mixtures imply that fuel composition greatly affects NOx emission levels44,45,46.

Combustion parameters

In cylinder pressure (crank angle vs. in- cylinder pressure in bar)

Figure 18 presents, for various fuel mixes, the in-cylinder pressure data as a function of different crank angles (CA), therefore providing interesting study of their combustion characteristics. By essentially adjusting crank angles, the table displays the phases of compression, combustion, and expansion strokes between − 40° and 40°. The fuel compositions examined are diesel, a mix of 20% Andropogon narudus (AN) biofuel with 80% diesel (referred to as ANB20-Diesel), and 20% Sapota Oil Methyl Ester (SOME) and 80% diesel (designated as SOME B20D). These also include ten ppm of either Cerium Oxide (CeO2) or Aluminium Oxide (Al2O3) nanoparticles47,48.

Figure 19 shows the peak pressure values of all the fuels and data analysis shows variations in fuel type and pressure matching varying crank degrees. At −40° CA, the observed pressure values for all fuel combinations are somewhat low, which corresponds with the compression stroke. These values cover diesel’s 1.4072 to the ANB20-Diesel combination with Al2O3’s 2.4353. As the crank angle reaches 0° CA and beyond—which characterizes the combustion phase—pressure increases somewhat dramatically. Peak pressure exhibits fluctuation over the many blends, which is a crucial element influencing combustion efficiency. Combining Al2O3 with 10° CA, the closest known measurement, the pressure values range from 34.1643 for diesel to 59.1220 for ANB20-Diesel. The ANB20-Diesel mix together with Al2O3 nanoparticles has the highest peak pressure, implying a more complete combustion process. Variance in the crank angle matching the peak pressure reveals details on the timing of combustion events. More exact findings depend on more research involving the construction of pressure-combustion angle diagrams and the computation of combustion parameters including heat release rate. Still, the results reveal that the type of biofuel (SOME rather than AN) and the usage of nanoparticles affect in-cylinder pressure, therefore affecting combustion performance49.

Net heat release rate (Crank angle vs. Net heat release rate in J/OCA

Analyzed both in the presence and absence of nanoparticle additives, Fig. 20 illustrates the net heat release rate (NHRR) across a range of crank angles (CA) for numerous fuel blends, including diesel, Sapota Oil Methyl Ester (SOME) blends, and Andropogon Narudus (AN) biofuel blends. The table defines the relevant interval connected to the combustion process by spanning crank angles between − 40° and 40°. Extensive from in-cylinder pressure data, the NHRR offers a measurement of the rate of energy release connected with the combustion process. The data analysis shows variations in the time and amplitude characteristics of heat emission connected with various fuel compositions. Around − 40° C, the NHRR readings approach zero, which matches expected behavior prior to combustion’s commencement. Starting and developing the combustion process, NHRR rises in line with the approaching 0° CA crank angle20.

Emphasizing the peak NHRR values obtained from Figs. 20 and 21 displays the greatest heat release attained for every blend during the combustion phase. Peak values determine most importantly the evaluation of combustion intensity and efficiency. For instance, the variance in peak Net Heat Release Rate (NHRR) between diesel and the SOME B20D80 mix is revealed. The SOME mix may aid to enable a more quick and complete combustion process since the peak NHRR for SOME B20D80 is essentially 5% more than that of diesel. Variations in fuel parameters affecting atomization and mixing characteristics might assist to explain this phenomenon. In the same line, a comparison of blends with nanoparticle additions to those without such additives can help to define the effect of these additives on the peak net heat release rate (NHRR). For example, adding CeO2 nanoparticles to the SOME B20D80 mix produces a 3% increase in peak Net Heat Release Rate (NHRR), implying that these nanoparticles function as combustion catalysts thereby allowing a rise in the reaction rate. The corresponding crank angle shows the timing of the peak Net Heat Release Rate (NHRR), which helps one to understand the phasing of combustion events. Advanced combustion phasing, defined by peak net heat release rate (NHRR), occurring at a former point in the cycle, may increase thermal efficiency. The observed variations in peak NHRR and their temporal characteristics highlight the significant role fuel composition and additives perform in the combustion process, therefore affecting general engine performance and emissions outputs9.

Results for sustainability assessment study using PUGH matrix

Criterion 1: performance factor

Brake Thermal Efficiency (BTE) represents the engine’s ability to convert fuel into mechanical output efficiently. At peak load conditions, diesel fuel in the PCCI engine exhibited lower BTE due to the absence of oxygen, resulting in a 0 W weightage. However, the inherent oxygen content in SOMEB20D80 and ANB20D80 facilitated the chemical reaction between oxygen and carbon molecules, warranting a + 1 W weightage. Furthermore, the addition of nanoparticles, i.e., CeO₂ and Al₂O₃, improved fuel atomization, reduced ignition delay, and combustion efficiency due to their high surface area and catalytic properties. Overall, these effects improved BTE, thus resulting in a + 2 W weightage for biodiesel with nanoparticles27.

BSFC is a measure to estimate the fuel energy content per brake power with respect to fuel calorific value. It is specifically significant in the case of biofuels because of the fluctuating calorific value of the latter. Two biofuels, Sapota Oil Methyl Ester and Andropogon Narudus Biodiesel were blended with diesel in the ratio of 20% (B20) and tested in an PCCI engine in the current work. The tests identified that the blends of biodiesel provided lower BSFC at all power output ranges. This is because the blends had higher oxygen content and lower viscosity, enabling a stoichiometric air-fuel ratio within the combustion chamber. Therefore, the biodiesel blends were given a weightage of 0 W, whereas diesel, which required more energy to produce a unit of brake power, was given a weightage of −1 W. In addition, the introduction of nanoparticles to the combustion chamber improved the combustion process because of their oxygen content and greater surface-to-volume ratio, improving combustion efficiency within the PCCI engine. Therefore, the biodiesel-nanoparticle blends were given a weightage of + 1 W50.

Criterion 2: environmental factor

The unburned HC emission formed because of insufficient oxygen present in the combustion chamber. HC emissions from an RCCI engine depend on a lot of things, like the fuel type, the injection strategy, the EGR rate, and the shape of the piston bowl. In the present work, the fuel type played a pivotal role in the formation of HC emissions. The diesel engine produced a higher amount of HC emissions because the lag of oxygen led to more combustion area covered by the non-stoichiometric combination fuel, hence claiming − 1 W weightage. Similarly, the SOMEB20D80 combination of the biodiesel produced more HC emissions, claimed because of the lower energy content and higher density of the fuel. Hence, SOMEB20D80 biofuel warranted − 1 W. But the ANB20D80 biodiesel blend claims 0 W weightage because of the higher latent heat vaporization characteristics that enhance the chemically correct mixture, which leads to reduced HC emissions. Also, adding nanoparticles to the biofuel mix makes the HC emission go up, which results in a −1 W weightage. The presence of metal-based particles in the combustion chamber alters the ignition delay period, resulting in a reduced premixed combustion phase, occasionally lowering the in-cylinder temperature, and increasing HC emission, which in turn suppresses the oxidation of HC molecules51.

Insufficient oxygen present in the combustion chamber leads to an increase in CO emission. The diesel engine claimed a −1 W weightage in the CO emission because of more CO emission caused by insufficient oxygen to convert all the molecules of carbon into CO₂. Diesel fuel gives off more CO than the SOMEB20D80 and ANB20D80. This is because oxygen in the combustion chamber and the fuel’s latent heat vaporization create more chemical mixtures. Hence, both the blends claim + 1 W. The nanoparticle-blended biodiesel was awarded + 2 W because the CeO₂ and Al₂O₃ enhance atomisation and motivate a better combustion rate52.

Complete combustion occurs when the engine transforms all hydrogen and carbon molecules into water and carbon dioxide. But the larger amount of CO2 emissions causes greenhouse gases and warnings against global warming. In the present research work, the RCCI engine produces a lower amount of CO₂ emissions when powered by diesel fuel; hence, the diesel was awarded + 1 W weightage. Furthermore, the fuel SOMEB20D80 and ANB20D80 produce more CO2 emissions as compared to other fuels. But the biodiesel used in the charge makes for more land usage, which leads to reduced CO2 emissions; hence, 0 W is assigned. The nanoparticle in the biodiesel blends promotes more complete combustion and oxidises the higher amount of carbon into carbon dioxide. Even though the biodiesel blend promotes the carbon life cycle, the nanoparticle still releases more CO₂ emissions; because of that, the nanoparticle warranted − 1 W53.

The NOx emissions are formed in the internal combustion engine at higher cylinder temperatures and pressures; during that condition, the nitrogen reacts with oxygen and produces the NOx emissions. Because diesel fuel doesn’t have any natural oxygen in it, it gives off less NOx when used in an RCCI engine than the other blend combination. This is why + 1 W is given. But the biodiesel produces a larger amount of NOx emissions because of two factors: the first is the presence of natural oxygen in the fuel, and the second is that the lower latent heat vaporization of the fuel promotes the chemically correct mixture, which leads to a higher amount of NOx emissions; hence, 0 W is assigned. This is because adding nanoparticles improves the ignition and combustion properties, which causes more NOxto be released and a −1 W assignment16,32.

The RCCI engine releases more smoke emissions because of incomplete combustion, which is similar to a diesel engine. However, the RCCI engine uses the two different fuels, which leads to a complex combustion process. When diesel fuel was added to the RCCI engine, a rich mixture of air and fuel formed in the combustion chamber. This caused more smoke to form and gave the engine a −1 W weightage. The density of the SOMEB20D80 fuel, when used in the engine, results in similar smoke formation. Because the fuel is denser, it makes bigger droplets, which prevents complete combustion. The same thing happened when the fuel was used with CeO₂ and Al₂O3, so the blend combination 1 W was recommended. But the ANB20D80 fuel and its combination of CeO₂ and Al₂O₃ produce the lower smoke formation caused by lesser viscosity and latent heat of vaporisation and assign + 1 W weightage for the fuel.

Criterion 3: economical factor

The ANB20D80 and SOMEB20D80 were claiming more economical benefit than diesel fuel because the biodiesel blends offer cost-effectiveness, provide energy security, and ensure long-term sustainability. The production of the biodiesel from non-edible crops lessens reliance on traditional fossil fuels. In contrast to diesel fuel, which experiences fluctuations in global crude prices, the local economy tends to stabilize biodiesel prices. The researchers identified that the biodiesel provides better lubricity than diesel fuel, which leads to reduced wear and tear on the engine, which means the biodiesel not only offers economic benefits but also longer engine life. The promotion of biodiesel contributes to mitigating climate change and reducing the carbon lifecycle. From the study, it was identified that the production of biodiesel has a significantly higher initial cost but long-term economic benefits, which include lower maintenance costs, energy security, and reduced environmental risk. Therefore, we have awarded + 1 W weights to ANB20D80 and SOMEB20D80, while diesel fuel claims 0 W. Adding nanoparticles to fuel makes it work better, but they are more expensive and take longer to make. Also, it’s important to know how to handle biodiesel that has nanoparticles mixed in. Hence, the nanoparticle-blended biodiesel blends were assigned − 1 W.

From the sustainability study, the ANB20D80 scored the highest value of + 5 W and ranked as I; further, the 10 ppm of the CeO₂ blend of the ANB20D80 scored + 3 W and ranked as II. The results indicate that Andropogon narudus provides sustainable fuel for the nation. Table 6 indicates the development of PUGH matrix. Figure 22 shows the aggregated scores of all the parameters developed from the experimental investigations. Figure 23 shows the kiviat plot of scores of all the parameters and their variation with the fuels used54.

Results and discussion of ML analysis

The evaluation of machine learning models for predicting thermal performance parameters demonstrates that the Random Forest (RF) algorithm exhibits superior predictive capability compared to Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) and Support Vector Machine Regression (SVMR). Among the parameters analyzed, RF achieved the highest accuracy for NOx (R² = 0.97), Smoke (R² = 0.99), and CO (R² = 0.95), underscoring its effectiveness in capturing complex nonlinear interactions inherent in engine performance and emission characteristics. The ability of RF to model intricate dependencies between operational variables makes it a highly suitable approach for optimizing engine efficiency and controlling emissions.

Conversely, MLR displayed strong predictive accuracy for BTE (R² = 0.99) and BSFC (R² = 0.94), suggesting that linear regression techniques are appropriate for parameters exhibiting strong linear correlations. However, the model’s performance declined significantly for CO₂ (R² = 0.40) and HC (R² = 0.64), indicating the presence of substantial nonlinearities in the combustion and emission processes. While MLR remains a useful tool for understanding fundamental thermal performance trends, its inability to fully capture complex emission dynamics limits its applicability in predictive modeling for advanced engine systems.

SVMR, on the other hand, exhibited the weakest predictive performance, particularly for Smoke (R² = 0.19), CO₂ (R² = 0.30), and BSFC (R² = 0.45), indicating its limited effectiveness in modeling thermal performance parameters. The suboptimal performance of SVMR may be attributed to challenges in selecting an appropriate kernel function for highly variable and nonlinearly distributed data. However, the model performed reasonably well in predicting CO (R² = 0.92) and NOx (R² = 0.94), highlighting its potential for application in selective emission modeling scenarios.

From a practical perspective, the outcomes of this study have significant implications for improving engine performance and emission control strategies. The superior predictive ability of RF can be leveraged for real-time engine control, enabling enhanced fuel efficiency and reduced environmental impact through adaptive operational tuning. The strong performance of MLR for BTE and BSFC suggests its applicability in refining combustion efficiency and fuel consumption models. Furthermore, the accurate prediction of NOx and CO emissions can aid in the development of proactive emission reduction strategies, particularly for regulatory compliance in the automotive and industrial sectors. The insights obtained from machine learning-based thermal performance modeling can also facilitate the development of next-generation hybrid and alternative fuel-powered engines, ensuring optimal performance while minimizing pollutant emissions.

In inclusive way, RF emerges as the most robust model for thermal performance prediction due to its ability to accurately capture both linear and nonlinear dependencies. While MLR proves beneficial for parameters with predominant linear relationships, SVMR’s effectiveness remains limited due to its relatively higher prediction errors. The graphical representation of these results is provided in Figs. 24 and 25, and 26, illustrating the predicted versus actual performance of each model and further reinforcing the superiority of RF in thermal performance estimation.

Conclusions

In summary, this research examined the performance, emissions, and combustion characteristics of varying compositions of Andropogon narudus biofuels and sapota oil methyl ester in a PCCI engine setup.

-

The findings showed that blending sapota oil methyl ester with an Al₂O₃ additive produced the highest brake thermal efficiency, and the Andropogon blends had lower brake-specific fuel consumption due to their lower viscosity.

-

The emission analysis reported a reduction in hydrocarbon emissions in the tested blends and reported CO₂ and NOx emissions more increased, attributing fuel composition compromise at the expense of emissions.

-

Combustion characteristics revealed that the introduction of Al₂O₃ contributed to the rate of pressure rise and heat release rate, both related to physical fuel properties.

-

Moreover, machine learning models, particularly Random Forest, were also good performers in predicting performance and emissions and thus have promise in the biofuel formulation optimization.

-

Sustainability analysis showed that AN20D80 is the most sustainable fuel blend, while machine learning analysis confirmed the best choice of biofuels with the best performance, emissions, and sustainability trade-off.

This research determines the need for advanced modelling techniques in order to foster the uptake of more efficient biofuels and minimal environmental harm.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Aceves, S. M., Flowers, D. L., Espinosa-Loza, F., Babajimopoulos, A. & Assanis, D. N. Analysis of premixed charge compression ignition combustion with a sequential fluid mechanics-multizone chemical kinetics model. SAE Tech. Papers. 115–2005. https://doi.org/10.4271/2005-01-0115 (2005).

Pradeep, V. & Anand, K. Novel strategies to extend the operating load range of a premixed charge compression ignited light-duty diesel engine. Fuel 317 (January), 123520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2022.123520 (2022).

Elumalai, P. V. et al. Combustion and emission behaviors of dual-fuel premixed charge compression ignition engine powered with n-pentanol and blend of diesel/waste tire oil included nanoparticles. Fuel 324 (PB), 124603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2022.124603 (2022).

Azizul, M. A. et al. Improvement of combustion process and exhaust emissions with premixed charge compression ignition. J. Automot. Powertrain Transp. Technol. 2 (1), 9–25. https://doi.org/10.30880/japtt.2022.02.01.002 (2022).

Kinikar, H. A., Kanasepatil, A. B. & Thipse, S. S. Influence of different biodiesel fuels on the PCCI-DI combustion concept for constant speed Genset application. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 1042 (1). https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/1042/1/012001 (2022).

Alemayehu, G., Firew, D., Nallamothu, R. B., Wako, A. & Gopal, R. Operating parameters optimization for lower emissions in diesel engine with PCCI-DI mode using Taguchi and grey relational analysis. Heliyon 8 (6), e09679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09679 (2022).

Agarwal, A. K., Singh, A. P. & Kumar, V. Particulate characteristics of low-temperature combustion (PCCI and RCCI) strategies in single cylinder research engine for developing sustainable and cleaner transportation solution, Environ. Pollut. 284(November 2020):117375, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117375

Ramachandran, E. et al. Prediction of RCCI combustion fueled with CNG and algal biodiesel to sustain efficient diesel engines using machine learning techniques. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 51 (103630). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2023.103630 (2023).

Kale, A. V. & Krishnasamy, A. Application of machine learning for performance prediction and optimization of a homogeneous charge compression ignited engine operated using biofuel-gasoline blends. Energy Convers. Manag. 314 (May), 118629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2024.118629 (2024).

Perumal Venkatesan, E. et al. jamesand Performance and emission reduction characteristics of cerium oxide nanoparticle-water emulsion biofuel in diesel engine with modified coated piston, Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26(26):27362–27371, (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-05773-z

Edwin Geo, V., Nagarajan, G., Nagalingam, B., Aloui, F. & Tazerout, M. A comparative analysis of different methods to improve the performance of rubber seed oil fuelled compression ignition engine. Fuel 280 (March), 118644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2020.118644 (2020).

Roschat, W. et al. A highly efficient and cost-effective liquid biofuel for agricultural diesel engines from ternary blending of distilled Yang-Na (Dipterocarpus alatus) oil, waste cooking oil biodiesel, and petroleum diesel oil. Renew. Energy Focus. 48 (January), 100540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ref.2024.100540 (2024).

Nguyen, V. N. et al. Engine behavior analysis on a conventional diesel engine combustion mode powered by low viscous Cedarwood oil/waste cooking oil biodiesel/diesel fuel mixture – An experimental study. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 184 (February), 560–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2024.02.002 (2024).

Joshua, P. J. T., Kandasamy, A., Venkatesan, E. P. & Saleel, C. A. Experimental study on sustainability involving the Pugh matrix on emission values of High-Temperature air in the premixed charged compression ignition engine. ACS Omega. 8 (44), 41243–41257. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c04694 (2023).

Ross, N. S., Mia, M., Anwar, S., Saleh, G. M., Ahmad, S. & M., and A hybrid approach of cooling lubrication for sustainable and optimized machining of Ni-based industrial alloy. J. Clean. Prod. 321, 128987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128987 (2021).

Sagin, S. V. et al. Use of biofuels in marine diesel engines for sustainable and safe maritime transport. Renew. Energy. 224 (February). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2024.120221 (2024).

Sivalingam, A. et al. Citrullus colocynthis - an experimental investigation with enzymatic lipase based Methyl esterified biodiesel. Heat. Mass. Transf. 55 (12), 3613–3631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00231-019-02632-y (2019).

Pan, D. et al. Study on the effect of Two-Stage injection strategy for Coal-to-Liquid/Gasoline Reactivity-Controlled compression ignition combustion mode. ACS Omega. 9 (16), 18191–18201. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c10315 (2024).

Perumal Venkatesan, E. et al. Performance and emission reduction characteristics of cerium oxide nanoparticle-water emulsion biofuel in diesel engine with modified coated piston. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 26 (26), 27362–27371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-05773-z (2019).

Venu, H., Raju, V. D., Lingesan, S., Elahi, M. & Soudagar, M. Influence of Al2O3nano additives in ternary fuel (diesel-biodiesel-ethanol) blends operated in a single cylinder diesel engine: performance, combustion and emission characteristics. Energy 215, 119091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2020.119091 (2021).

Ali, M., Kashif, M., Zaidi, A. A. & Jamil, R. Statistical optimization of biodiesel production from Non-edible Pongamia Pinnata oil. Period Polytech. Chem. Eng. 68 (3), 419–427. https://doi.org/10.3311/PPch.36753 (2024).

Qiu, Y., Lan, X., Liu, J., Wang, G. & Huang, Z. Optimization design of nozzle parameters under the condition of submerged water jet breaking soil based on response surface method. Appl. Ocean. Res. 154, 104369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apor.2024.104369 (2025).

Lionus Leo, G. M., Jayabal, R., Kathapillai, A. & Sekar, S. Performance and emissions optimization of a dual-fuel diesel engine powered by cashew nut shell oil biodiesel/hydrogen gas using response surface methodology. Fuel 384 (133960). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2024.133960 (2025).

Gurusamy, M. & Subramanian, B. Study of PCCI engine operating on pine oil diesel blend (P50) with benzyl alcohol and diethyl ether, Fuel 335(x):127121, (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2022.127121

Zhang, H. et al. Innovative free radical induced synthesis of WO3-doped diethyl Malonate grafted Chitosan encapsulated with phosphorylated alginate matrix for UO22 + adsorption: parameters optimisation through response surface methodology. Sep. Purif. Technol. 353 (128455). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2024.128455 (2025).

Padmanaban, J. et al. Sustainability study and SWOT analysis of mixed biofuel blends in engine at various injection pressure analysed by experimentally and statistically. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 31574. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79073-z (2024).

Padmanaban, J., Kandaswamy, D. A., Joshua, P. J. T. & Natarajan, A. Statistical analysis of engine fueled with two identical lower aromatic biofuel blends at various injection pressure. Energy Sources Part. Recover Util. Environ. Eff. 46 (1), 7720–7735. https://doi.org/10.1080/15567036.2024.2368495 (2024).

Ramalingam, K. et al. An assessment on production and engine characterization of a novel environment-friendly fuel. Fuel 279 (118558). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2020.118558 (2020).

Ramalingam, K., Vellaiyan, S., Kandasamy, M., Chandran, D. & Raviadaran, R. An experimental study and ANN analysis of utilizing ammonia as a hydrogen carrier by real-time emulsion fuel injection to promote cleaner combustion. Results Eng. 21 (February), 101946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.101946 (2024).

Prashanth, K. & Srihari, S. Emission and performance characteristic of a PCCI-DI engine fueld with cotton seed oil bio-diesel blends. ARPN J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 11 (9), 5965–5970 (2016).

Ramalingam, K., Kandasamy, A. & Chellakumar, P. J. T. J. S. Production of eco-friendly fuel with the help of steam distillation from new plant source and the investigation of its influence of fuel injection strategy in diesel engine. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 26 (15), 15467–15480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-04773-3 (2019).

Ramalingam, K. et al. An assessment on production and engine characterization of a novel environment-friendly fuel. Fuel 279 (May), 118558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2020.118558 (2020).

Venu, H. et al. A comprehensive combustion, performance, and environmental analyses of algae biofuel, hydrogen gas, and nano-sized particles (liquid-gas-solid mix) in agricultural CRDI engines. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 73 (April), 839–855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.05.209 (2024).

Rahman Adib, A. et al. Novel biofuel blends for diesel engines: optimizing engine performance and emissions with C. cohnii microalgae biodiesel and algae-derived renewable diesel blends. Energy Convers. Manag X. 23 (August), 100688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecmx.2024.100688 (2024).

Le, T. T. et al. An experimental assessment of waste transformer oil and palm oil biodiesel blended with diesel fuel on A single cylinder direct in diesel engine. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 14 (1), 246–258. https://doi.org/10.18517/ijaseit.14.1.15998 (2024).

Krishnamoorthi, M., Malayalamurthi, R., He, Z. & Kandasamy, S. A review on low temperature combustion engines: performance, combustion and emission characteristics. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 116 (109404). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2019.109404 (2019).

Kale, A. V. & Krishnasamy, A. Experimental study addressing the challenges of homogeneous charge compression ignition combustion in a light-duty diesel engine using multiple biofuels. J. Clean. Prod. 469 (July), 143122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.143122 (2024).

Parthasarathy, M. et al. Performance analysis of HCCI engine powered by Tamanu Methyl ester with various Inlet air temperature and exhaust gas recirculation ratios. Fuel 282 (August), 118833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2020.118833 (2020).

Mohanasundaram, K. R. & Govindan, N. Effect of air preheating, exhaust gas Re-Circulation, and hydrogen enrichment on biodiesel/methane dual fuel engine. Therm. Sci. 25 (1), 449–464. https://doi.org/10.2298/TSCI191024146M (2021).

Chen, H., Wang, X. & Pan, Z. Effect of operating conditions on the chemical composition, morphology, and nano-structure of particulate emissions in a light hydrocarbon premixed charge compression ignition (PCCI) engine. Sci. Total Environ. 750, 141716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141716 (2021).

Venu, H., Raju, V. D., Subramani, L. & Appavu, P. Experimental assessment on the regulated and unregulated emissions of DI diesel engine fuelled with Chlorella Emersonii Methyl ester (CEME). Renew. Energy. 151, 88–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2019.11.010 (2020).

Caranton, A. R. G. et al. Enhancing performance and emission characteristics of palm based biodiesel blends with aeronautical additives: A comprehensive analysis in a J69 aviation engine. Energy Convers. Manag. 313 (May). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2024.118600 (2024).

Kumaran, P., Natarajan, S., Kumar, S. M. P., Rashid, M. & Nithish, S. Optimization of diesel engine performance and emissions characteristics with tomato seed blends and EGR using response surface methodology. Int. J. Automot. Sci. Technol. 7 (3), 223–233. https://doi.org/10.30939/ijastech.1326036 (2023).

van Kessel, L. B., Arendsen, A. R., de Boer-Meulman, P. D. & Brem, G. The effect of air preheating on the combustion of solid fuels on a grate. Fuel 83 (9), 1123–1131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2003.11.008 (2004).

Elkelawy, M., Shenawy, E. A., El, Mohamed, S. A., Elarabi, M. M. & Bastawissi, H. A. E. Impacts of using EGR and different DI-fuels on RCCI engine emissions, performance, and combustion characteristics. Energy Convers. Manag X. 15 (May), 100236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecmx.2022.100236 (2022).

Singh, A. P., Kumar, D. & Agarwal, A. K. Introduction to Alternative Fuels and Advanced Combustion Techniques as Sustainable Solutions for Internal Combustion Engines, ISBN 9789811615122, (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-1513-9_1

Ramachandran, E., Krishnaiah, R., Perumal Venkatesan, E., Medapati, S. R. & Sekar, P. Experimental investigation on the PCCI engine fueled by algal biodiesel blend with CuO nanocatalyst additive and optimization of fuel combination for improved performance and reduced emissions at various load conditions by RSM technique. ACS Omega. 8 (8), 8019–8033. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.2c07882 (2023).

Sanyasi Rao, S., Paparao, J., Raju, M. V. J. & Kumar, S. Effect of nanoparticle-doped biofuel in a dual-fuel diesel engine with oxy-hydrogen gas. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 70 (April), 146–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.05.131 (2024).