Abstract

For patients with low-grade endometrioid carcinoma of stage T1a, the role of lymphadenectomy in staging surgery remains controversial. This study aims to evaluate the impact of lymphadenectomy on cancer-specific survival (CSS) in this patient population using a large, population-based dataset. We conducted a retrospective analysis using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, identifying 11,014 patients with stage T1a, low-grade endometrioid carcinoma from 2004 to 2015. Patients were divided into lymphadenectomy and non-lymphadenectomy groups. Propensity score matching (PSM) was performed to balance baseline characteristics. Kaplan-Meier analysis, log-rank tests, and multivariate Cox regression were used to assess CSS and identify independent prognostic factors. Before PSM, the non-lymphadenectomy group had higher CSS compared to the lymphadenectomy group (HR = 1.56, 95% CI: 1.16–2.10, p = .003). After 1:1 PSM, CSS was similar between the two groups (HR = 1.09, 95% CI: 0.78–1.53, p = .605). Subgroup analyses showed no significant differences in CSS except for the subgroup with tumor size > 2 cm, where non-lymphadenectomy was associated with better CSS (HR = 0.50, p = .035). Multivariate Cox regression analysis identified age, marital status, histological grade, and chemotherapy as independent prognostic factors for CSS, while lymphadenectomy was not (p = .980).. Our findings suggest that lymphadenectomy does not improve CSS in patients with low-grade endometrioid carcinoma of stage T1a.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, uterine cancer ranks as the sixth most prevalent form of cancer among women and the 14th most common cancer in general. In 2018, there were more than 380,000 new diagnoses of this disease1. The increasing prevalence of endometrial cancer is largely due to the rise in obesity rates and the aging population2. Consequently, mortality rates have been increasing by an average of 1.9% per year, primarily because of the growing obesity problem, which is the most significant known risk factor for endometrial cancer3,4. 80% of endometrial cancers are localized within the uterus at the time of diagnosis, often manifesting as postmenopausal bleeding5. This typical symptom facilitated early detection, which leaded to earlier treatment and better tumor outcomes6.

For individuals with endometrial cancer, the standard surgical treatment involves a complete extrafascial hysterectomy along with the removal of both fallopian tubes and ovaries, as well as an assessment of the pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes7. Regarding the need for systematic lymphadenectomy, Mayo criteria (Pathological type of endometrioid carcinoma; Myographic infiltration does not exceed 50%; Histological grade was G1 or G2; Tumor size ≤ 2 cm) have been widely used in clinical practice to judge whether patients are at low risk of lymph node metastasis. Patients who do not meet the above criteria may be high risk of lymph node metastasis and should be considered for systemic lymphadenectomy8,9. However, these data are difficult to accurately evaluate before the final pathological diagnosis is made, and some centers use intraoperative freezing pathology to assist decision-making, and avoid systematic lymphadenectomy if the return results meet the above criteria10.

It is still controversial to avoid systematic lymphadenectomy in staging surgery for patients with early-staged endometrial cancer11. Therefore, based on a large amount of data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, this study included patients with low-grade endometrioid carcinoma of stage T1a to further verify and explore the above controversial issues in terms of cancer-specific survival (CSS).

Methods

Data source

The SEER database is a comprehensive cancer statistics database managed by the National Cancer Institute. It collects data on the incidence, prevalence, survival, and mortality rates of cancer in each region of the United States. This study used the SEER-17 dataset from 2000 to 2021, covering approximately 26.5% of the total U.S. population. Considering SEER database is publicly available and does not require informed patient consent, therefore, ethical approval and informed consent were waived.

Patient selection

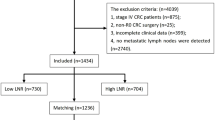

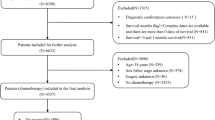

In this study, we identified primary endometrial cancer cases from 2004 to 2015 in the SEER-17 data set using the codes C54.1. All patients underwent either simple hysterectomy or (modified) radical hysterectomy at the primary site (Surgery Codes: A400, A500, A600, A610; A620; A630; A640; A650; A660; A670). All patients had endometrioid carcinoma (8380/3), with a histological grade of either Grade I or Grade II. The T stage of all patients was T1a and the M stage was M0. The study was limited to adults aged 18 years and older, all of whom were histologically confirmed. During the screening process, we excluded cases with unknown lymph node evaluation methods and those with local lymph node biopsy or aspiration. In addition, we excluded patients with unclear information on oncology outcomes, as well as patients with 2 or more primary site tumors. Last but not least, patients whose marital status was unknown at diagnosis, as well as cases with missing information in residence and race, were not included in the final analysis. In the end, 11,014 patients were enrolled in the study. The patient selection process is shown in Fig. 1.

Variable processing

Based on the coding system of the SEER database, we obtained patients’ demographic characteristics (including age, marital status, median household income, place of residence, race and ethnicity), oncology characteristics (including histological grade, and tumor size), and treatment measures (radiotherapy, and chemotherapy). In addition, we determined CSS based on the patient’s final state and duration of follow-up.

In the subsequent statistical analysis, we divided the age at diagnosis into ≤ 60 years and > 60 years, and the marital status at diagnosis into married and unmarried (including single, separated, divorced, widowed, and unmarried or domestic partner). Median household income was classified as < 75,000 USD and ≥ 75,000 USD, place of residence as urban and rural, racial groups as black, white, and other (Asian or Pacific Islander and American Indian/Native Alaska), and ethnic groups as Hispanic and non-Hispanic. Histological grade was classified into Grade I and Grade II. Tumor size was classified as ≤ 2 cm and > 2 cm.

Statistical analysis

The patients were divided into non-lymphadenectomy group and lymphadenectomy group. Differences in baseline features between the two groups were determined by Pearson Chi-square test. The tumor outcome measure we were interested in was CSS. Kaplan-Meier curves and Log-rank tests were used to assess differences in CSS between the two groups. Subsequently, to reduce the impact of baseline differences on survival, we performed 1:1 propensity score matching (PSM). After PSM, Kaplan-Meier curves and Log-rank tests were used again to assess the effects of two groups on CSS. In addition, subgroup analyses were performed based on predetermined variables. Finally, multivariate COX regression analysis was used to find the independent predictive factors on CSS. All statistical analyses in this study were performed using R software (version 4.3.0). All P-values were bilateral, and the threshold of significance was set at 0.05.

Results

Patient baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the included patients are shown in Table 1. A total of 11,014 patients were included, with a median follow-up of 127 months. Among them, 5,145 (46.7%) patients had lymphadenectomy and 5,869 (53.3%) patients did not. There were 7,380 patients (67.0%) aged ≤ 60 years, and 3,634 patients (33.0%) aged > 60 years. In terms of demographics, most patients were married (59.8%), white (82.3%), non-Hispanic (87.4%), had a median household income of more than 75,000 USD (53.7%), and lived in urban (88.2%). In terms of tumor characteristics, there were 8,336 (75.7%) well differentiated (Grade I) patients, and 2,678 (24.3%) moderately differentiated (Grade II) patients. For tumor size of the primary site, 3,433 (31.2%) patients were ≤ 2 cm, 3,115 (28.3%) patients were > 2 cm, and 4,466 (40.5%) patients were unknown. In terms of treatment, 209 patients (1.9%) received radiotherapy, and 52 patients (0.5%) received chemotherapy.

Before PSM, significant differences were observed between non-lymphadenectomy group and lymphadenectomy group in various aspects, including age (p < .001), median household income (p < .001), place of residence (p < .001), race (p < .001), ethnicity (p = .013), histological grade (p < .001), tumor size (p < .001), radiotherapy (p < .001), and chemotherapy (p < .001). After 1:1 PSM, the analysis included 4,397 patients who did not undergo lymphadenectomy and 4,397 patients who underwent lymphadenectomy.

Survival outcomes

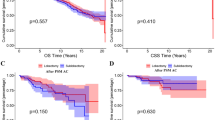

Before PSM, the CSS of the non-lymphadenectomy group is slightly higher than that of the lymphadenectomy group (HR = 1.56, 95% CI: 1.16–2.10, p = .003, Fig. 2). After adjustment with 1:1 PSM, the CSS of the non-lymphadenectomy group is similar to that of the lymphadenectomy group (HR = 1.09, 95% CI: 0.78–1.53, p = .605, Fig. 3). Table 2 details the differences in CSS at key time points of 12 months, 36 months, and 60 months for the two groups before and after PSM.

In subgroup analyses, as depicted in Fig. 4, except for the subgroup with tumor size > 2 cm, where CSS was superior in the non-lymphadenectomy group compared to the lymphadenectomy group (HR = 0.50, p = .035), there were no significant differences in CSS between the two groups for all other subgroups.

In the multivariate Cox regression analysis, age, marital status, histological grade, and chemotherapy were identified as independent prognostic factors for CSS (p < .05). However, lymphadenectomy was not an independent prognostic factor for CSS (p = .980). The results of the Cox regression analysis are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Discussion

The status of lymph node metastasis in patients with endometrial cancer is an important indicator of accurate staging, which can evaluate prognosis and guide adjuvant treatment. Previously, the NCCN guidelines recommended comprehensive staging surgery for all early-stage endometrial cancer patients, which included pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy. However, as evidence accumulated, it became clear that certain early-stage endometrial cancer patients have a very low risk of lymph node metastasis, and omitting lymphadenectomy does not affect prognosis. In recent years, the standard of care for lymph node management in early-stage endometrial cancer has evolved. According to the Mayo criteria, it is now recommended to perform sentinel lymph node biopsy or lymphadenectomy in patients with high-risk disease, while omitting lymphadenectomy in low-risk patients. Although lymphadenectomy is required for accurate staging, but its therapeutic value is controversial. On the one hand, the rate of lymph node metastasis in patients with early endometrial cancer is low, and the health and economic benefits of lymphadenectomy remain to be discussed. The rate of lymph node metastases varies with tumor stage and grade, from 3 to 5% in minimally invasive low-grade tumors to > 20% in high grade deep myometrial invasive tumors12. Literatures reported that the rate of preoperative diagnosis of pelvic lymph node metastasis in patients with clinical stage I endometrial cancer ranges from 3.6–13.3%13. On the other hand, for early-stage endometrial cancer, the results of multiple studies have indicated that lymphadenectomy does not improve the oncological outcomes for patients, may lead to an increased incidence of related complications, and affects the quality of life of the patients13,16,17,18,19,20. Complications associated with lymphadenectomy include damage to blood vessels and nerves during the operation; development of a deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolus during the postoperative period; and lymphoedema and/or pelvic lymphocyst formation. These complications can be particularly severe or disabling. Notably, lymphedema and lymphocyst formation may be underreported or underrecognized, especially in studies focused on short-term outcomes. Two randomized clinical trials are the most representative. A study by Pierluigi Benedetti Panici et al., focusing on patients with stage I endometrial cancer, found that systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy was associated with a higher incidence of postoperative complications, but it did not improve patients’ disease-free survival or overall survival, and only significantly improved the surgical staging statistically13. MRC ASTEC trial, which included 1408 preoperatively histologically confirmed endometrial cancers limited to the body of the uterus, found no evidence that pelvic lymphadenectomy was beneficial for overall survival or recurrence-free survival in women with early-stage endometrial cancer and did not recommend pelvic lymphadenectomy as a routine procedure for treatment19.

Our study focused on patients with low-grade endometrioid carcinoma of stage T1a and included 11,014 patients eventually. After analysis, we found that before PSM, the CSS of patients in the non-lymphadenectomy group was even better than that of patients in the lymphadenectomy group (p = .003), but after PSM, there was no statistically significant difference in CSS between the two groups (p = .605), that is, the CSS of patients in the non-lymphadenectomy group was no worse than that of patients in the lymphadenectomy group. Our findings are consistent with the conclusions of the two randomized clinical trials above, supporting the avoidance of systemic lymphadenectomy in clinical practice for patients with low-grade endometrioid carcinoma of stage T1a.

However, some studies have put forward different perspectives, mainly covering two aspects. First, there are still studies indicating that lymphadenectomy is the most important prognostic factor for endometrial cancer, and the extent of lymphadenectomy improves the survival rates of patients with medium/high-risk endometrioid endometrial cancer21,22,23,24,25,26. Moreover, lymphadenectomy is crucial for accurate surgical staging21. Second, completing surgical staging can reduce the use of adjuvant radiotherapy and offers the highest cost-effectiveness27.

To avoid overtreatment, an increasing number of experts are recommending a more selective and individualized lymph node evaluation method called sentinel lymph node dissection (SLND). Multiple retrospective and prospective studies have demonstrated the safety and accuracy of SLND for low-risk endometrial cancer (defined as stage I, grade I, or grade II endometrioid histology)28,29. Based on these robust published studies, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) has included SLND in its management guidelines for patients with endometrial cancer30. Because SLND is accompanied by pathological ultra-staging, the detection rate of lymph node metastases in patients undergoing SLND is 5–15% higher than in patients undergoing systemic lymphadenectomy31. And compared with systemic lymphadenectomy, SLND was associated with shorter operative time, less blood loss and a lower risk of lymphedema32,33.

To ensure the reliability of our findings, we conducted subgroup analyses and multivariate Cox regression analysis. The results indicated that lymphadenectomy did not improve CSS for patients with low-grade endometrioid carcinoma of stage T1a in nearly all subgroups. Moreover, the multivariate Cox regression analysis revealed that lymphadenectomy was not an independent prognostic factor for CSS in these patients. It is noteworthy that in the subgroup with tumor size > 2 cm, our study showed that patients who did not undergo lymphadenectomy had higher CSS than those who did, which seems counterintuitive. Commonly, larger tumor size is associated with a higher rate of lymph node metastasis, and lymphadenectomy is generally beneficial for the oncological outcome in endometrial cancer patients with high lymph node metastasis possibility. However, our study yielded the opposite result, possibly due to below two main factors. First, the overall positive outcome event rate in early-stage endometrial cancer is very low (only 1.56% in our study). Specifically, in patients with tumor size > 2 cm, the positive outcome event rate was 2.10% in the lymphadenectomy group and 1.05% in the non-lymphadenectomy group. These low event rates may lead to low statistical power and instability in the results. Second, a significant proportion of patients (40.5%) had unknown tumor sizes, and the prognostic information related to lymphadenectomy and tumor size for these patients is unknown, which may influence the statistical outcomes. Our study also found that age and marital status were independent prognostic factors for early-stage endometrial cancer patients, consistent with some other studies34,35,36,37, suggesting that in treating these patients, attention should not be focused solely on the physical disease but also on providing sufficient psychological support and companionship to achieve better treatment outcomes. Chemotherapy was previously considered ineffective for stage I endometrial cancer patients and did not improve survival rates compared to radiotherapy38,39. Our study results align with this conclusion, indicating that chemotherapy is not an independent protective factor for CSS in early-stage endometrial cancer patients. Instead, chemotherapy emerged as an independent risk factor for CSS, possibly due to the low incidence of adjuvant therapy in the patients included in the study, inevitably leading to statistical bias.

Our study has the following strengths. First, the SEER database is one of the world’s largest cancer databases, containing a vast amount of patient data, which significantly enhances the statistical power and representativeness of our study. Second, the SEER database is an open database, meaning that all statistical analyses are reproducible, which is a considerable advantage. Moreover, the use of PSM and multivariate Cox regression analysis minimized the impact of baseline characteristic differences and covariates on the outcomes, increasing the reliability of our conclusions. However, our study also has certain limitations. First, due to the nature of the SEER database, we were unable to obtain all variables that might affect prognosis, such as lifestyle factors, specific radiotherapy or chemotherapy regimens, and dosages. Although PSM effectively balanced known confounding factors between the two groups, there may still be unmeasured confounding factors affecting the results. Second, the retrospective design of this study may introduce selection bias and information bias, although we have taken measures to minimize these biases as much as possible. Third, we cannot access detailed treatment plans and the rationale behind them, which complicates our understanding of certain counterintuitive findings. For instance, in our study, the lymphadenectomy rate for T1a low-grade endometrioid carcinoma was as high as 46.7%. Fourth, the SEER database lacks critical pathological features such as lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI) and molecular subtyping, which are related to lymph node metastasis and prognosis. This limits our ability to further explore risk factors for lymph node metastasis using this database. Fifth, a significant proportion of patients (40.5%) in our study had unknown tumor sizes. Including these patients as a separate category in the multivariate Cox regression may lead to ambiguity in identifying independent prognostic factors for CSS.

Conclusion

Lymphadenectomy does not improve CSS in patients with low-grade endometrioid carcinoma of stage T1a. It can be considered to reduce lymphadenectomy in such patients during staging surgery, with the aim of minimizing complications and economic burden associated with lymphadenectomy without affecting oncological outcomes.

Data availability

The data used in this study are all available through the SEER database.

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 68 (6), 394–424 (2018).

Morrison, J. et al. British gynaecological Cancer society (BGCS) uterine cancer guidelines: recommendations for practice. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 270, 50–89 (2022).

Lauby-Secretan, B. et al. Body fatness and Cancer–Viewpoint of the IARC working group. N Engl. J. Med. 375 (8), 794–798 (2016).

Rahib, L. et al. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the united States. Cancer Res. 74 (11), 2913–2921 (2014).

Morice, P., Leary, A., Creutzberg, C., Abu-Rustum, N. & Darai, E. Endometrial cancer. Lancet 387 (10023), 1094–1108 (2016).

Oaknin, A. et al. Endometrial cancer: ESMO clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 33 (9), 860–877 (2022).

Concin, N. et al. ESGO/ESTRO/ESP guidelines for the management of patients with endometrial carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 478 (2), 153–190 (2021).

Milam, M. R. et al. Nodal metastasis risk in endometrioid endometrial cancer. Obstet. Gynecol. 119 (2 Pt 1), 286–292 (2012).

Neubauer, N. L. & Lurain, J. R. The role of lymphadenectomy in surgical staging of endometrial cancer. Int. J. Surg. Oncol. 2011, 814649 (2011).

Bodurtha Smith, A. J., Fader, A. N. & Tanner, E. J. Sentinel lymph node assessment in endometrial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 216 (5), 459–476e10 (2017).

Korkmaz, V. et al. Comparison of three different risk-stratification models for predicting lymph node involvement in endometrioid endometrial cancer clinically confined to the uterus. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 28 (6), e78 (2017).

Nahshon, C., Kadan, Y., Lavie, O., Ostrovsky, L. & Segev, Y. Sentinel lymph node sampling versus full lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer: a SEER database analysis. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 33 (10), 1557–1563 (2023).

Benedetti Panici, P. et al. Systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy vs. no lymphadenectomy in early-stage endometrial carcinoma: randomized clinical trial. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 100 (23), 1707–1716 (2008).

Chi, D. S. et al. The incidence of pelvic lymph node metastasis by FIGO staging for patients with adequately surgically staged endometrial adenocarcinoma of endometrioid histology. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 18 (2), 269–273 (2008).

Todo, Y. et al. Isolated tumor cells and micrometastases in regional lymph nodes in stage I to II endometrial cancer. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 27, e1 (2016).

Barton, D. P., Naik, R. & Herod, J. Efficacy of systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (MRC ASTEC Trial): a randomized study. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 19 (8), 1465 (2009).

Frost, J. A., Webster, K. E., Bryant, A. & Morrison, J. Lymphadenectomy for the management of endometrial cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015 (9), CD007585 (2015).

Frost, J. A., Webster, K. E., Bryant, A. & Morrison, J. Lymphadenectomy for the management of endometrial cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 10 (10), CD007585 (2017).

Kitchener, H., Swart, A. M., Qian, Q., Amos, C. & Parmar, M. K. Efficacy of systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (MRC ASTEC trial): a randomised study. Lancet 373 (9658), 125–136 (2009).

May, K., Bryant, A., Dickinson, H. O., Kehoe, S. & Morrison, J. Lymphadenectomy for the management of endometrial cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (1), CD007585 (2010).

Abu-Rustum, N. R. et al. Is there a therapeutic impact to regional lymphadenectomy in the surgical treatment of endometrial carcinoma. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 198 (4), 457e1–457e5 (2008). discussion 457.e5-6.

Chan, J. K. et al. Therapeutic role of lymph node resection in endometrioid corpus cancer: a study of 12,333 patients. Cancer 107 (8), 1823–1830 (2006).

Otsuka, I. Therapeutic benefit of systematic lymphadenectomy in Node-Negative Uterine-Confined endometrioid endometrial carcinoma: omission of adjuvant therapy. Cancers (Basel). 14, 4516 (2022).

Ignatov, A. et al. Systematic lymphadenectomy in early stage endometrial cancer. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 302, 231–239 (2020).

Chang, S. J. et al. Para-aortic lymphadenectomy improves survival in patients with intermediate to high-risk endometrial carcinoma. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 87, 1361–1369 (2008).

Saotome, K. et al. Impact of lymphadenectomy on the treatment of endometrial cancer using data from the JSOG cancer registry. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 64, 80–89 (2021).

Cohn, D. E., Huh, W. K., Fowler, J. M. & Straughn, J. M. Jr Cost-effectiveness analysis of strategies for the surgical management of grade 1 endometrial adenocarcinoma. Obstet. Gynecol. 109 (6), 1388–1395 (2007).

Daraï, E. et al. Sentinel node biopsy for the management of early stage endometrial cancer: long-term results of the SENTI-ENDO study. Gynecol. Oncol. 136 (1), 54–59 (2015).

Holloway, R. W. et al. Sentinel lymph node mapping and staging in endometrial cancer: A society of gynecologic oncology literature review with consensus recommendations. Gynecol. Oncol. 146 (2), 405–415 (2017).

Holtzman, S. et al. Outcomes for patients with high-risk endometrial cancer undergoing Sentinel lymph node assessment versus full lymphadenectomy. Gynecol. Oncol. 174, 273–277 (2023).

Bogani, G., Raspagliesi, F., Leone Roberti Maggiore, U. & Mariani, A. Current landscape and future perspective of Sentinel node mapping in endometrial cancer. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 29 (6), e94 (2018).

Abu-Rustum, N. R. Sentinel lymph node mapping for endometrial cancer: a modern approach to surgical staging. J. Natl. Compr. Canc Netw. 12 (2), 288–297 (2014).

Segarra-Vidal, B. et al. Minimally invasive compared with open hysterectomy in High-Risk endometrial Cancer. Obstet. Gynecol. 138 (6), 828–837 (2021).

Chen, Z. H. et al. Assessment of modifiable factors for the association of marital status with Cancer-Specific survival. JAMA Netw. Open. 4 (5), e2111813 (2021).

Dong, J., Dai, Q. & Zhang, F. The effect of marital status on endometrial cancer-related diagnosis and prognosis: a surveillance epidemiology and end results database analysis. Future Oncol. 15 (34), 3963–3976 (2019).

Lowery, W. J. et al. Survival advantage of marriage in uterine cancer patients contrasts poor outcome for widows: a surveillance, epidemiology and end results study. Gynecol. Oncol. 136 (2), 328–335 (2015).

Yuan, R., Zhang, C., Li, Q., Ji, M. & He, N. The impact of marital status on stage at diagnosis and survival of female patients with breast and gynecologic cancers: A meta-analysis. Gynecol. Oncol. 162 (3), 778–787 (2021).

Maggi, R. et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy vs radiotherapy in high-risk endometrial carcinoma: results of a randomised trial. Br. J. Cancer. 95 (3), 266–271 (2006).

Susumu, N. et al. Randomized phase III trial of pelvic radiotherapy versus cisplatin-based combined chemotherapy in patients with intermediate- and high-risk endometrial cancer: a Japanese gynecologic oncology group study. Gynecol. Oncol. 108 (1), 226–233 (2008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concepts: Kaige Pei & Mingrong XiStudy design: Kaige Pei & Mingrong Xi Data acquisition: Kaige Pei & Dongmei Li Quality control of data and algorithms: Mingrong XiData analysis and interpretation: Kaige Pei & Dongmei Li Statistical analysis: Kaige Pei & Dongmei Li Manuscript preparation: Kaige Pei & Dongmei LiManuscript editing: Kaige Pei & Mingrong XiManuscript review: Kaige Pei & Mingrong Xi.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pei, K., Li, D. & Xi, M. The impact of lymphadenectomy on cancerspecific survival in patients with low-grade endometrioid carcinoma of stage T1a. Sci Rep 15, 15952 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00531-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00531-3