Abstract

The shale oil phase state is essential for assessing shale oil production, establishing development plans, and enhancing oil recovery. Previous studies on shale oil phase state mainly focused on bulk fluid phase based on fluid composition retrieved from drill holes, while nano-confined shale oil phase state based on subsurface in-situ fluid compositions is rarely discussed. In this work, we established a new workflow that used pressure-preserved shale cores and pyrolysis gas chromatogram (Py-GC) to retrieve in-situ shale oil compositions from various shales with different thermal maturities. The workflow includes retrieving pressure-preserved shale cores, cutting, transporting, and then preparing samples under the protection of liquid nitrogen; the new process makes the evaporation loss of lightweight hydrocarbons the least. By comparison, fluid samples from wellheads and wellbores were also retrieved from Gulong shale oil reservoirs in the Songliao Basin. Both bulk and nano-confined shale oil phases were then analyzed, and the results showed that methane content in the Gulong shale oil increased from 10.11 to 23.39% with increasing thermal maturity; by contrast, C7+ hydrocarbons decreased from 64.73 to 41.13%. As for bulk fluid phases, Gulong shale oils are black oil phases, while in terms of nano-confined fluid phases, their phases are controlled by thermal maturity. They are black oil phases at lower thermal maturity with vitrinite reflectance (Ro) less than 1.4% and are condensate phases at higher thermal maturity with Ro greater than 1.4%. Shale oil production data showed that nano-confined phase analysis using in-situ shale oil compositions from pressure-preserved cores can best predict shale oil production in this study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The initial shale oil phase state and its dynamics during development are crucial to assessing shale oil production, improving the production decline curve, and enhancing oil recovery. In contrast to conventional reservoirs, shale reservoirs are dominated by nanopores1, where the effects of capillary force, pore structure, fluid-solid interaction, and intermolecular force on the shale oil phase state cannot be ignored2. In nanopores, molecules are arranged more orderly, which decreases free volume and affects intermolecular interactions. As a result, critical temperatures and pressures of the phase state in nanopores are different from those in conventional reservoir pores, where the liquid phase will be transformed to a denser mesophase, neither a typical liquid phase nor a typical gas phase. Therefore, the classical phase state equation faces several challenges in estimating the shale oil phase state. The critical shift of fluid phases in nanospace has been observed in nanofluidic chips3,4, and several researchers have modified conventional phase state equations to evaluate petroleum phase behavior in nanopores5,6,7,8. However, most studies use a single pure component or a mixture of several pure components, instead of actual subsurface or in-situ fluid compositions. Retrieving original subsurface fluids is another challenge for shale oil phase study. First, shale oil reservoirs are artificial reservoirs, which means that shale oil migrates from matrix pores to fracking fractures and then to drill holes, where shale oil compositions and physical properties will change. Therefore, fluid samples retrieved from bottom wellbores and wellheads are distinct from in-situ fluid in composition9,10. For example, a long-time observation showed that stable carbon isotope of methane dissolved in the Gulong shale oil varied with time due to the adsorb-desorb effect in tight shale layers11. Secondly, shale oil production is accompanied by many fracturing fluids; as a result, bottom-hole oil sampling is rarely successful. Thirdly, gases and lightweight hydrocarbons evaporate rapidly because shale oils are usually light in density, making gas-oil ratios hard to determine. Therefore, estimating shale oil phase states by wellhead fluid is unreliable. Additionally, nano-confinement effects in shale oil reservoirs make fluid retained in pores longer, enhance adsorbed gas formation, and reduce the number of free hydrocarbons, increasing development difficulty. Therefore, studying nano-confinement shale oil phase states has theoretical and practical values.

In this study, taking the Gulong shale oil in the Songliao Basin as a case, based on hydrocarbon compositions from pressure-preserved cores, bottom-hole oil samples, and well-head oil samples, both bulk and nano-confined shale oil phase states were analyzed; shale oil phase states were revealed to change with thermal maturity and pore sizes. The results will improve our understanding of shale oil production mechanisms in nanopores and provide theoretical and technical support for enhancing shale oil recovery.

Geological setting and shale reservoir characteristics

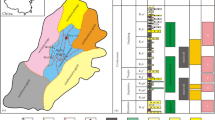

The Songliao Basin (Fig. 1), located in northeast China, has a total area of 260,000 km2 and is characterized by a dual structure with the Lower Cretaceous developing fault basin and the Upper Cretaceous developing large-scale depression basin. The Lower Cretaceous strata developed a gas-containing system with organic-rich Shahezi Formation shale as the primary source rock; the Upper Cretaceous strata developed an oil-containing system with organic-rich Qingshankou Formation and Nenjiang Formation shales as the dominant source rocks. During the Late Cretaceous in the Songliao Basin, two large-scale sea transgressions formed the Qingshankou and Nenjiang organic-rich shales, respectively. The Qingshankou Formation shales were deposited in a semi-deep and deep lake, covering an area of over 18 × 104 km2 with a thickness ranging from 90 to 360 m12, total organic carbon content (TOC) averaging at 2.37%, and primary organic matter of type I13. The average initial hydrogen index (HI) is 750 mg/gTOC; the overall thermal maturity is higher, with most vitrinite reflectance (Ro) higher than 0.75% and the highest up to 1.67%. The wide variation in thermal maturity is mainly caused by differences in thermal history within the basin. Overall, the thermal maturity is related to burial depth. For instance, the most mature source rocks are in the southern Qijia-Gulong Sag, which is the deepest; by contrast, source rocks in Sanzhao Sag are shallower and less mature.

The Gulong shale oils are mainly developed in the Qingshankou 1st member and the lower part of the Qingshankou 2nd member, with free oil content (S1) in the range of 4–15 mg/g (avg. 7.0 mg/g). The Gulong shale oils are enriched in multiple layers within the Qingshankou Formation and exhibit continuous distribution in transverse, with a favorable area of 1.46 × 104 km2. Most of the Gulong shale oils are accumulated in the mid-lower part of the Qingshankou 1st member; the lower part of the Qingshankou 2nd member has an oil-bearing thickness ranging from 140–180m14. Different from shale oils in other basins around the world, the Gulong shale oils are retained oils that have not experienced migration15, which means that shale oil maturity is in accordance with in-situ shale thermal maturity.

The shale oil reservoirs have small pore sizes, mainly at 2–300 nm, most are smaller than 100 nm. With the increase of thermal maturity, pore size decreases accordingly. At the high thermal maturity stage, pore size is dominated by 2–30 nm, with pore-throat diameter generally less than 10 nm11. In the meantime, bedding fractures are developed, with micro-nano fractures developed up to tens of thousands per meter, which increases with higher thermal maturity15.

Samples and methods

Samples in this study are pressure-preserved cores from 7 wells, 2 wellhead oils, and a bottom-hole oil (Fig. 1). Cores are shales of the Qingshankou 1st and 2nd members in the Gulong sag and Sanzhao sag, encompassing a wide range of thermal maturity. Sample information, such as formation temperature, pressure, and gas-oil ratio (GOR) based on production data, is listed in Table 1.

Shale oil composition analysis of pressure-preserved cores

Pressure-preserved core sample Preparation

The Gulong shale oils are light, suggesting that lightweight hydrocarbons could be lost nearly completely using conventional cores and analysis workflow16. To avoid such defects, we established a new workflow based on pressure-preserved cores to retrieve in-situ shale oil compositions, with the least loss of lightweight hydrocarbons. The core barrel used to fetch pressure-preserved cores in this study had a two-layer structure, with the inner cylinder filled with sealing fluid (i.e., castor oil). During drilling, shale cores entered the inner cylinder and were sealed by the sealing fluid, which would have effectively kept light hydrocarbons from escaping and prevented drilling fluid from penetrating. The inner cylinder was a 5–6 m long steel tube equipped with a built-in pressure gauge to detect potential pressure release and light hydrocarbon loss. At the end of drilling, the inner cylinder with shale cores was insulated by a ball valve and ready to be pulled out of the wellbore. At the surface, the pressure of the inner cylinder was required to be greater than 80% of the in-situ formation pressure, ensuring that the pressure was kept well. After validating the pressure, the inner cylinder with shale cores was immediately placed in a tank full of liquid nitrogen and frozen for 4–6 h. Then, under the protection of liquid nitrogen, the inner cylinder was cut into pieces about 1.0 m in length, which were later stored in a barrel with liquid nitrogen and transported to a laboratory. In the laboratory, in the liquid nitrogen freezing state, the steel layer of the inner cylinder was removed to get shale cores, which were then stored in a cryogenic container with liquid nitrogen. Though there might be a small number of light hydrocarbon losses, to the best of our knowledge, the process introduced in this study can keep the most primary fluids in cores.

Pyrolysis chromatography (Py-GC)

Rock-eval technology has been widely used to determine shale oil content17; the pyrolysis S1 indicates free hydrocarbons released at 300 °C for 3 min. To obtain shale oil composition, a Shimadzu GC-14B gas chromatograph was used in this study, equipped with a steel reaction vessel to release free hydrocarbons in shale by heating. First, the frozen core pieces were quickly cut into small particles about 1–2 mm in diameter and then placed in the steel reaction vessel. Then, the vessel was heated at 300 °C for 3 min, and the released hydrocarbons from shales were carried by helium gas and collected in a cold trap. The pyrolysis chromatogram analysis was conducted based on China Petroleum Industrial Standard SY/T 6188 − 2016. As for gas chromatography analysis, an HP-5 (60 m×0.25 mm i.d., phase thickness 0.25 μm) column was used. The GC oven was programmed from 30 °C to 315 °C at 3 °C/min and held isothermally at 315 °C for 20 min. The carrier gas was helium.

Bottom-hole fluid sampling and Wellhead fluid combination

Bottom-hole fluid sampling followed the workflow proposed by China Petroleum Industrial Standard SY/T5154-2014, which requires that the bottom-hole pressure is greater than the initial fluid saturated pressure, and the water production rate is less than 5%. When wells could not meet the standard for bottom-hole fluid sampling, wellhead fluids were used instead. To get an accurate gas-oil ratio, which was later used to recombine wellhead liquid and gas compositions to get the whole fluid composition, the production nozzle was adjusted to make reservoir fluid enter the borehole under pressure over the bubble point pressure. When the producing gas-oil ratio did not decrease with the decrease in oil production, the gas-oil ratio was thought to represent the subsurface gas-oil ratio. The process followed China National Standard GB/T 26981 − 2020.

Nano-confined shale oil phase state simulation

Compared to conventional sand reservoirs, shale reservoirs have much smaller pore sizes, mainly from a few nanometers to tens of nanometers; as a result, nano-confined effects on pore fluid and its behavior could be significant. Conventional fluid phase equations (e.g., Peng-Robinson) are based on bulk fluid phase and are unable to be used to estimate fluid phase changes and mobility in the nanoscale. There are three main issues regarding phase behavior in nanopores. First, it does not include pore wall potential field and long-range intermolecular forces; therefore, critical pressures and temperatures are inaccurate. Second, the formation of the adsorption layer and the capillary condensation effect are not considered; as a result, the free phase ratio and fluidity are overestimated. Thirdly, the multi-component competitive adsorption and diffusion energy barriers are simplified, resulting in distortion of component differentiation and mass transfer efficiency. Accordingly, a modified Peng-Robinson equation of state (PR-EOS) was applied in this study, based on a previous study18.

Critical pressure and temperature adjustment

Many studies2,6,19,20 have shown that direct application of conventional equations of phase states, such as Peng-Robinson equation of state (PR-EOS), to estimate nano space fluid phase behavior can lead to deviation. Therefore, we applied equations (Eqs. 1 − 2) proposed by Zarragoicoechea and Kuz7 to shift critical pressures and temperatures according to pore size in nano space, to adapt nano-confined fluid phase state evaluation.

In Eqs. (1 − 2), Tc and Pc are conventional critical temperature and pressure, respectively, while Tcm and Pcm are nano-confined critical temperature and pressure, respectively. The unit of pressure is atm., while that of temperature is K. The σlj is the Lennard-Jones parameter associated with fluid molecular size, and the unit is nm. The rp is the radius of a pore, and the unit is nm.

Capillary force adjustment

In conventional micro-scale reservoirs, capillary force in a pore-throat can be ignored; thus, most current flash models do not count capillary force, which means that PV=PL (i.e., Pcap=0). However, in nanopores, the capillary force will affect gas and liquid balance, and thus cannot be ignored. The capillary force can be obtained by:

Where gas-liquid interfacial force can be evaluated by Parachor model21:

Where ρ is molar density (mol/m3), [P] is the Parachor parameter of a pure component (cm3/mol), and Pcap is the capillary force between gas and liquid (MPa).

Phase state calculation

Assuming an oil reservoir consists of n components with a total mole number of 1.0, if gas and liquid are in balance, the following equations are fulfilled.

where V is the mole fraction of gas, L is the mole fraction of liquid, and zi is the total mole number for the ith component.

When the phase is balanced, gas fugacity equals liquid fugacity, and through iterative computations, flash calculation was conducted. To get different phase states varying with shale physical properties and model production curves for a well, a MATLAB program for simulating phase behavior was coded to include parameters, including porosity, permeability, and pore size.

Results

Hydrocarbon composition of Gulong shale oils from pressure-preserved cores

As shown in Fig. 2, compared with conventional core samples, hydrocarbons detected from pressure-preserved cores using the new workflow proposed here have the least loss in lightweight hydrocarbons (e.g., C1 − 14). In comparison, conventional Gulong shale oil samples with a density of less than 0.80 g/cm3 have gas hydrocarbon content (C1 − 5) ranging from 0.22 to 7.73%, which is significantly lower than pressure-preserved cores; by contrast, C7+ content ranges from 87.25 to 98.13%, which is much higher. As the increase of thermal maturity (denoted by vitrinite reflectance, i.e., Ro), methane content increases from 10.11 to 23.39%, while C7+ content decreases from 64.73 to 41.13% (Fig. 3; Table 1).

The hydrocarbon compositions of Gulong shale oils presented here are similar to those of Eagle Ford shale oils, of which the gas oil ratio (GOR) ranges 130–446m3/m322. Similarly, most of the producing GOR of Gulong shale oils lies in this range, except for the well ZY1, the producing GOR of which was not detected; based on compositions of pressure-preserved cores, its GOR is estimated at 11.7. It is worth noting that due to the adsorption of hydrocarbons by clay minerals22, heavy-end hydrocarbons (e.g., C22+) might be underestimated by the current workflow. Based on bulk fraction analysis of 32 Gulong shale oils, they are dominated by saturates ranging from 85.2 to 92.4%, whereas asphaltenes, most likely retained by clay minerals, account for only 0.2–3.9%. Moreover, as indicated by high-temperature gas chromatography (HTGC) that is used to detect C40 + high-molecular-weight alkanes in crude oils23, asphaltenes contain mainly C40- ranging from 51.08 to 82.93% (Fig. 4). As shown in Fig. 4b, only those of lower thermal maturity have an increased number of unresolved complex mixture (UCM), which could have been from kerogen partition24. Heavy-end hydrocarbons adsorbed by clay minerals could be partially restored by an exponential law between carbon number and molar content as illustrated in Sect. "Bottom-hole fluid sampling and Wellhead fluid combination"; thus, they might not significantly affect phase analysis results in current cases.

Molar distributions of hydrocarbons from pressure-preserved cores

Molar distributions of alkanes in natural crude oils without post-alteration follow an exponential law regarding their carbon numbers25. The exponential law was previously used to correct the loss of lightweight hydrocarbons in shale oil26,27. However, as shown in Fig. 5, it is evident that gas components (C1-4) have different slopes compared to liquid components (C5+). The slope discontinuity in alkane distribution has also been reported by Thompson (2002)28, showing that hydrocarbon compositions from pressure-preserved cores might represent in-situ shale oil composition the best. By comparison, an oil evaporation experiment was conducted with different exposure times in atmospheric conditions. The result shows that with the increase of exposure time, lightweight hydrocarbons continue to lose; still, heavyweight hydrocarbons follow the exponential law (linear law in semi-log plot), with the lowest carbon number following the exponential law increasing from 8 to 11. As previously mentioned, clay minerals will affect heavyweight hydrocarbons, which is shown by the significant decrease of C20+ components (e.g., Well GY5 and GY2 in Fig. 5a).

Bottom-hole and Wellhead fluid compositions

In this study, only one bottom-hole oil sample was successfully retrieved from Well GY2 after adjusting the oil nuzzle and well soaking several times. The initial formation temperature, pressure, and oil saturation pressure were 111.1 °C, 35.5 MPa, and 26.1 MPa, respectively. Before sampling, the producing gas oil ratio had been stable at around 292.7m3/m3 for 27d, and the bottom fluid pressure was 28.4 MPa during sampling; besides, there was no indication of degassing in the wellbore. The corresponding GOR for this well was 266m3/m3, which was determined by single degassing. The hydrocarbon compositions of this oil sample are shown in Table 2, with the methane content at 15.08%, ethane at 3.70%, C3 -6 at 7.92%, and C7+ at 73.30%.

In comparison, two shale oil samples were retrieved from wellheads (Well GY1 and GY8), and their hydrocarbon compositions were determined by recombining oil and gas components by producing GOR. The initial stable GOR of Well GY1 is 520m3/m3, while that of Well GY8 is 181m3/m3. The recombined hydrocarbon composition of the shale oil sample from GY1 is that methane is 21.2%, with ethane at 8.45%, C3-6 at 18.6%, and C7+ at 51.75%. The recombined hydrocarbon composition of the shale oil sample from GY8 is that methane is 7.68%, with ethane at 3.22%, C3-6 at 8.28%, and C7+ at 80.82%.

Discussion

Effects of lightweight hydrocarbon loss and heavyweight hydrocarbon adsorption on phase behavior

To understand the effect of lightweight hydrocarbons and heavyweight hydrocarbons on shale oil phase behaviors, phase envelopes of shale oils with different losses of lightweight hydrocarbons16 and with heavyweight hydrocarbons restored based on the exponential law proposed by Kissin25, were compared. The results are shown in Fig. 6. It is evident that with increasing loss of lightweight hydrocarbons, the critical temperature increases while the critical pressure decreases more significantly from 19.3 to 2.2 MPa. In contrast, heavyweight hydrocarbon adsorption seems to have little effect on the critical temperatures and pressures, with the critical temperature slightly increasing from 193.1 to 199.1˚C, and the critical pressure remaining nearly the same.

(a) The phase envelope changes with increasing exposure time of pressure-preserved shale cores, showing the effect of light-weight hydrocarbon loss on phase behavior, and (b) The phase envelope using the original hydrocarbon composition from a pressure-preserved core, compared to that using heavyweight hydrocarbon restored hydrocarbon composition, indicating the effect of heavyweight hydrocarbon adsorption on the phase behavior.

Bulk fluid phase States and reservoir fluid phase type

Bulk fluid phase envelopes were solved by the software PVT-sim, using PR-EOS and hydrocarbon compositions from pressure-preserved cores, and the results are shown in Fig. 7. It is evident that all Gulong shale oils are black oil phases. Similarly to Eagle Ford shale oils29, the critical pressures and temperatures tend to decrease as thermal maturity increases. Based on bulk fluid phase state analysis, overall, Gulong shale oils are black oil phases; however, with changes in critical temperatures and pressures, bulk shale oil phases tend to transform from black oil phases to condensate phases.

Comparisons of oil phase analysis results from different sampling methods, including pressure-preserved cores, recombing oil and gas at the surface, and subsurface in-situ oil sampling, were conducted (Fig. 8). As shown in Fig. 8a, concerning Well GY1, the phase envelope from the wellhead oil is fatter than that from the oil from pressure-preserved cores, with critical pressures significantly higher for the wellhead oil. Wellhead oils tend to lose more lightweight hydrocarbons; therefore, lightweight hydrocarbons might have more control over critical pressures, which is also evident in Fig. 6a. In contrast, concerning Well GY2 (Fig. 8b), the phase envelope from the bottom hole oil is also fatter than that from the oil from pressure-preserved cores, but with a significant difference in the critical temperature. Compared to pyrolysis hydrocarbon compositions of pressure-preserved cores, bottom-hole oils have more heavyweight hydrocarbons, indicating that heavyweight hydrocarbons might have more control over critical temperatures, which is also implied in Fig. 6b. Overall, oils retrieved from pyrolysis of pressure-preserved cores have higher contents of gas and lightweight hydrocarbons, which decreases both critical pressures and temperatures. Theoretically, the intermolecular forces between lightweight hydrocarbons are relatively weaker, indicating that lower energy is needed to overcome these forces to make liquid evaporate. As a result, oils with more lightweight hydrocarbons are prone to reach their critical states at lower temperatures and pressures. In summary, to obtain more representative subsurface shale oil phases, we suggest using hydrocarbon compositions with heavyweight hydrocarbon restoration.

Nano-confined fluid phase States and reservoir fluid phase types

Gulong shale oil reservoirs are dominated by nanopores, which exhibit significant confinement to fluid phase behavior and significantly impact shale oil exploitation8. Therefore, reservoir engineers have continuously invested much in studying confined shale oil phase states18.

Shale oil phase behavior under different pore sizes

Using nano-confined phase state analysis on hydrocarbon compositions from pressure-preserved shales, shale oil phase envelopes at different pore sizes were calculated. As shown in Fig. 9; Table 3, the smaller the pore size, the lower the critical temperatures and pressures. With decreasing pore size, shale reservoir fluid phases transform from black oil phases to condensate phases. With pore size smaller than 150 nm, most confined fluid phase envelopes deviate from bulk fluid phase envelopes; in contrast, with pore size smaller than 10 nm, most shale oils are condensate phases. Depending on shale oil compositions, phase confinement effects exhibit differences. Overall, lower thermal mature shale oils consist of more heavyweight hydrocarbons; thus, a smaller maximum pore size is required for the conversion of black oil phases to condensate phases. For example, the Ro of Well ZY1 is 0.96%, and black oil phases can be transformed into condensate phases when the pore size is smaller than 10 nm. In contrast, as for Well GY1 with Ro at 1.67%, black oil phases can be transformed into condensate phases when the pore size is less than 150 nm. Full-scale pore size analysis shows that, with increasing thermal maturity, the peak pore size distribution of Gulong shales changes from 500 nm to 2–8 nm (Table 3)11. Therefore, it is suggested that phase confinement effects are trivial for shales with Ro less than 1.2%, and shale oils are mainly black oil phases. In contrast, at mid-high thermal maturity (Ro = 1.2–1.4%), phase confinement effects intensify; although shale oils are still dominated by black oil phases, there are some condensate phases. At high thermal maturity (Ro > 1.4%), phase confinement is most profound, and shale oils are mainly condensate phases.

Reservoir fluid phase distribution

Based on the above results of shale oil phases in different pore sizes, coupling of Gulong shale thermal maturity spatial variation13 and full-scale pore size evolution characteristics11, the reservoir fluid phase distribution of Gulong shale oil was revealed. As shown in Fig. 1, shale reservoirs with black oil phases (denoted by green and yellow colors) have an area of 1.4 × 104km2, mainly in north Qijia Sag, Heiyupao Sag, south Daqing Anticline, slope areas of Qijia-Gulong Sag, and Sanzhao Sag. Oil density in the black oil phase area ranges from 0.81 to 0.86 g/cm3. In contrast, condensate phase reservoirs (denoted by orange hue) have an area of 758 km2, mainly in the Gulong Sag, where the oil density is usually less than 0.81 g/cm3. These areas are the favorite Gulong shale oil exploiting targets.

Phase state and shale oil production prediction

Shale oil reservoirs have narrow pore throats, where the interaction of pore walls will enhance intermolecular diffusion. In the meantime, molecules are more likely to be affected by pore walls; therefore, the fluid will move along the pore wall surface and increase the diffusion rate. As a result, fluid molecules close to pore walls are likely to perform slip flow. The slip flow will reduce the drag force when the fluid flows through pores, improving fluid mobility. The nano-confinement makes phase envelopes smaller than bulk fluid phases, indicating that under initial formation pressures and temperatures, the fluid saturation pressure is lower, resulting in a later occurrence of two-phase flow and favoring keeping solution gas drive8. Conventional oil reservoir numerical simulations do not account for the effect of nano-confinement on production; however, the effect cannot be ignored in shale oil production. To estimate the effect of nano-confinement on oil reservoir numerical simulation and indicate characteristics of hierarchical flow in multiscale porous media, shale oil compositions retrieved from wellheads, bottom-holes, and pressure-preserved cores were used in combination with nano-confined phase models, upon which several shale oil well production curves were determined.

Employing CMG to conduct reservoir simulation with different phase models, as shown in Fig. 10a, production curves with time are best fitted by confinement models; in contrast, the predicted cumulative oil production is the lowest from the wellhead fluids with the bulk phase model. As for Well GY2 (Fig. 10b), the current fluid flow pressure is ca. 25 MPa, higher than the bubble point pressure, implying that the solution gas drive is dominated. Accordingly, the predicted cumulative oil productions by both bulk and confinement models based on pressure-preserved cores are similar and are closer to production data. As for GY8 (Fig. 10c), the advantage of the confinement model based on pressure-preserved cores is most evident, indicating that wellhead and bottom-hole oils may not be appropriate for the prediction of oil production and reservoir fluid phase type identification.

Conclusions

Shale reservoirs, particularly those rich in clay minerals, have complex pore structures dominated by nanopore sizes ranging from 1 to 100 nm; different from conventional reservoirs and tight sand or carbonate reservoirs, many effects, including capillary forces, adsorption effects, inter-molecular forces, could be too big to be ignored. Moreover, how to get accurate or representative in-situ shale oil compositions is still a challenge. In this study, based on an innovative combined usage of the pore-size confined phase model and pressure-preserved cores to get in-situ shale oil composition, we have made some progress, and some conclusions are summarized as follows, which will benefit the understanding of fluid flow in shale reservoirs and improve production decline curves.

(1) Bulk hydrocarbon compositions retrieved from pressure-preserved cores can better represent shale reservoir in-situ fluid compositions. As increasing thermal maturity, in the Gulong shale oils, methane content increases from 10.11 to 23.39% while C7+ content decreases from 64.73 to 41.13%.

(2) Bulk fluid phase state analysis suggests that Gulong shale oils are dominated by black oil phases. And only in those areas with Ro greater than 1.6%, reservoir oil phases will be changed to condensate phases.

(3) Confinement phase states and reservoir fluid phases analysis show that Gulong shale oils with thermal maturity of less than 1.4% are dominated by black oil phases, mainly in the north Qijia Sag, Heiyupao Sag, south Daqing Anticline, slope areas of Qijia-Gulong Sag, and Sanzhao Sag. In contrast, in those areas with thermal maturity greater than 1.4%, oil physical properties are better, and shale oils are mainly condensate phases, mainly in the Qijia-Gulong Sag, the core area of Gulong shale oil exploitation.

(4) Gulong shale oil long-time production data show that nano-confined phase models can predict data production better, indicating that conventional bulk fluid phase analysis is inappropriate for identifying shale oil reservoir fluid phase type and production prediction.

Still, several issues need to be addressed, such as the effect of extremely heavy components, which might contain partial kerogen and occlude nanopores, on phase behavior. The other issue we have not addressed is that hydrocarbon composition could be different in pores of different sizes, which will also significantly affect phase behavior. It needs us to develop finer models in the future.

Data availability

Data in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zou, C. et al. First discovery of nano-pore throat in oil and gas reservoir in China and its scientific value. Acta Petrologica Sinica. 27, 1857–1864 (2011).

Liu, X. & Zhang, D. A review of phase behavior simulation of hydrocarbons in confined space: implications for shale oil and shale gas. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 68, 102901 (2019).

Bao, B. & Zhao, S. A review of experimental nanofluidic studies on shale fluid phase and transport behaviors. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 86, 103745 (2021).

Zhong, J. et al. Nanoscale phase measurement for the shale challenge: multicomponent fluids in multiscale volumes. Langmuir 34, 9927–9935 (2018).

Singh, S. K., Sinha, A., Deo, G. & Singh, J. K. Vapor – liquid phase coexistence, critical properties, and surface tension of confined alkanes. J. Phys. Chem. C. 113, 7170–7180 (2009).

Song, Y. et al. Fluid phase behavior in multi-scale shale reservoirs with nano-confinement effect. Energy 289, 130027 (2024).

Zarragoicoechea, G. J. & Kuz, V. A. Critical shift of a confined fluid in a nanopore. Fluid. Phase. Equilibria. 220, 7–9 (2004).

Yuan, S. et al. Key theoretical and technical issues and countermeasures for effective development of Gulong shale oil, Daqing oilfield, NE China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 50, 638–650 (2023).

Whitson, C. H. & Sunjerga, S. PVT in Liquid-Rich Shale Reservoirs. SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, 155499 (2012).

Jarvie, D. M., Jarvie, B. M., Weldon, W. D. & Maende, A. Geochemical assessment of petroleum in unconventional resource systems. SPE/AAPG/SEG Unconventional Resources Technology Conference, 875–894 (2015).

Sun, L. et al. Formation mechanisms of nano-scale pores/fissures and shale oil enrichment characteristics for Gulong shale, Songliao basin. Oil Gas Geol. 44, 1350–1365 (2023).

Hou, Q., Feng, Z. & Feng, Z. Continental Petroleum Geology of Songliao Basin654 (Petroleum Industry, 2009).

Feng, Z., Huo, Q., Zeng, H., Wang, Y. & Jia, Y. Organic matter compositions and organic pore evolution in Gulong shale of Songliao basin. Petroleum Geol. Oilfield Dev. Daqing. 40, 40–55 (2021).

Zhu, G. et al. Enrichment conditions and favorable zones for exploration and development of continental shale oil in Songliao basin. Acta Petrolei Sinica. 44, 110–124 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. In-situ hydrocarbon formation and accumulation mechanisms of micro- and nano-scale pore-fracture in Gulong shale, Songliao basin, NE China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 50, 1269–1281 (2023).

Zeng, H. et al. A comparison of hydrocarbon loss between pyrolysis S1 and crude oils: A case study of Qingshankou shale-oil system, Songliao Basin. 30th International Meeting on Organic Geochemistry 2021, 1–2 (2021).

Jarvie, D. M. in Shale Reservoirs—Giant Resources for the 21st Century Vol. 97 AAPG Memoir (ed J. A. Breyer) 1-519American Association of Petroleum Geologists, (2012).

Zhao, G. et al. Initial occurrence state and movability evaluation of the Gulong shale oil reservoir. Songliao Basin Energies. 17, 1358 (2024).

Chen, X. et al. Phase behavior of hydrocarbon fluids in shale reservoirs, considering pore geometries, adsorption, and water film. ACS Omega. 9, 2104–2112 (2024).

Liu, B. et al. Comprehensive outlook into critical roles of pressure, volume, and temperature (PVT) and phase behavior on the exploration and development of shale oil. Energy Fuels. 36, 14534–14553 (2022).

Weinaug, C. F. & Katz, D. L. Surface tensions of Methane-Propane mixtures. Industrial Eng. Chem. 35, 239–246 (1943).

Wang, F., Feng, Z., Wang, X. & Zeng, H. Effect of organic matter, thermal maturity and clay minerals on pore formation and evolution in the Gulong shale, Songliao basin, China. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 223, 211507 (2023).

Feng, Z. et al. Distribution and significance of C40 + alkanes in the extracts of cretaceous source rocks from the Songliao basin. Sci. China Ser. D: Earth Sci. 50, 1510–1520 (2007).

Bandurski, E. Structural similarities between Oil-Generating kerogens and petroleum asphaltenes. Energy Sources. 6, 47–66 (1982).

Kissin, Y. V. Catagenesis and composition of petroleum: origin of n-alkanes and isoalkanes in petroleum crudes. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 51, 2445–2457 (1987).

Michael, G. E., Packwood, J. & Holba, A. Determination of In-Situ Hydrocarbon Volumes in Liquid-Rich Shale Plays. AAPG Search and Discovery, 80365 (2014).

Ma, W., Li, J. & Wang, M. Determination of in situ hydrocarbon contents in shale oil plays: part 3: quantification of light hydrocarbon evaporative loss in old cores based on preserved shales. Mar. Pet. Geol. 160, 106574 (2024).

Thompson, K. F. M. Compositional regularities common to petroleum reservoir fluids and pyrolysates of asphaltenes and kerogens. Org. Geochem. 33, 829–841 (2002).

Kuske, S., Horsfield, B., Jweda, J., Michael, G. E. & Song, Y. Geochemical factors controlling the phase behavior of eagle Ford shale petroleum fluids. AAPG Bull. 103, 835–870 (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jiamin Lu: Project manager and resources. Huasen Zeng : Writing, reviewing and editing; conception. Qingzhen Wang: Writing , methodology, sofware. Zihui Feng: Writing and reviewing; conception. Hang Jiang: Data curation. Rui Wang: Resources. Binhui Li: Data curation, resources. Qiuli Huo: Data curation, resources. Longde Sun: Reviewing, conception, and reviewing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, J., Zeng, H., Wang, Q. et al. Phase behavior of nanoconfined continental shale oil and reservoir fluid phases in the Gulong shale of the Songliao basin. Sci Rep 15, 16210 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00543-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00543-z