Abstract

The primary focus of this study involved the fabrication of a novel nanocatalyst Fe3O4-supported asparagine functionalized graphene oxide Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine). The catalyst was synthesized through a four-step procedure. The chemical composition of Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine) was examined using various analytical methods, including scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and a Raman. The Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine) catalyst demonstrated remarkable catalytic action in the synthesis of 5-oxo-dihydropyrano[3,2-c]chromenes as well as dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole derivatives. The protocol offered several benefits, including short reaction times, the utilization of green solvents, outstanding product yields, and a straightforward work-up procedure. Eventually, density functional theory (DFT) computations were utilized to calculate several parameters, including energy levels, electrostatic potential, and chemical reactivity descriptors based on highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energies. Based on the calculations obtained from DFT, it was determined that the type and position of functional groups on the synthesized compounds had the most significant impact on the calculations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent decades, increasing health and environmental concerns have driven the development of eco-friendly industrial processes and sustainable chemical reactions1. Meanwhile, multicomponent reactions (MCRs) have emerged as a valuable method for the efficient, one-pot synthesis of complex molecules. Therefore, MCRs offer several advantages, including waste reduction, enhanced energy efficiency, improved yields, and shorter reaction times2.

In recent years, heterogeneous catalysts have gained widespread application as environmentally friendly materials, attracting significant interest for their use in various industrial processes, organic transformations, and synthetic applications3. Among the extensively studied nanomaterials, carbon nanomaterials have garnered significant attention as environmentally friendly and efficient catalysts for various chemical and industrial processes. This interest stems from their remarkable properties, including high corrosion resistance, air stability, and cost-effectiveness3. Carbon nanomaterials have garnered attention for their exceptional properties and diverse applications in materials science, energy, and catalysts4,5.

Among carbon nanomaterials, Graphene oxide (GO) is air-stable carbocatalyst widely utilized as a heterogeneous, metal-free oxidative catalyst in various chemical transformations1,6. The chemical structure of GO is of considerable importance due to the presence of various functional groups, including hydroxyl, epoxy, and carboxyl groups. Notably, the presence of functional groups makes GO an exceptionally convenient starting material for a wide range of chemical reactions7.

A major challenge in industrial catalysis and the synthesis of chemical and pharmaceutical materials is the separation of catalysts at the end of the reaction. In order to overcome this issue, nowadays, magnetic heterogeneous catalysts are effectively and efficiently used for the synthesis of organic compounds, particularly heterocycles in multi-component reactions8. Magnetic nanoparticles are widely used for the preparation of various heterogeneous catalysts due to their unique features such as high surface area, environmentally friendly characteristics, magnetic susceptibility, catalytic activity, and easy separability3.

Among the various heterocyclic compounds, 4 H-chromenes, also known as coumarins, are organic compounds with a benzopyran structure9. These compounds have a wide range of biological activities, including antimicrobial, antithrombotic, antipsychotic, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer properties10. Due to their diverse biological effects, 4 H-chromenes have generated interest in pharmaceutical research10. The most common and important methods reported for the synthesis of 4 H-chromenes use a three-component condensation reaction involving aldehydes, malononitrile, and 1,3-diketones3. Different catalytic systems were used in the previously mentioned reactions, including CeCl3·7H2O11, and proline12, under various reaction conditions, each with its drawbacks. Some of these drawbacks include high cost, environmental unfriendliness, manufacturing complexity, and other associated challenges9.

Furthermore, Pyrano[2,3-c]pyrazoles, due to their unique and unparalleled characteristics in the pharmaceutical and biotechnological industries, have captured the attention of scientists13. One of the common and significant methods for its synthesis and derivatives is the use of three-component reactions between aldehydes, 3-methyl‐1‐phenylpyrazolin‐5‐one, and malononitrile3. Various catalysts have been employed for the synthesis of this category of compounds, such as piperidine14, triethylammonium acetate (TEAA) ionic liquid15, γ‐Fe2O3@Cu3Al‐LDH16, and cupreine17. In addition, we have recently delineated a straightforward, productive, single-step synthesis of pyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole derivatives by employing Fe3O4@GOQD-O-(propane-1-sulfonic acid)18 as highly effective, sustainable nanocatalysts with magnetic properties.

Herein, novel and green nanocatalysts are currently being developed for the catalysis of MCRs to synthesize heterocyclic compounds. In this paper, the fabrication and characterization of Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine) are described. Furthermore, its ability to serve as a green, effective, and reusable catalyst in the one-pot synthesis of 4 H-chromenes (4a-i) and dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazoles (5a-h) (Fig. 1) is investigated. In addition, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were used to determine the various parameters of synthesized production (4a-i) and (5a-h). These parameters encompass energy levels, electrostatic potential, chemical reactivity descriptors, etc. These values were determined through the analysis of EHOMO and ELUMO. Furthermore, the B3LYP/6-31G** level was incorporated by the Orca package. This allows us to conduct ground-state geometry optimizations and assess the electronic features of the molecules under investigation.

Materials and methods

Hierarchical catalyst synthesis process

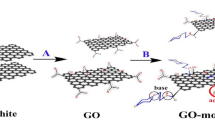

The synthesis procedure was initiated by fabricating GO using a previously mentioned modified version of the Hummers method3,19. Hummer’s method is particularly suitable for the oxidation of graphite to produce GO because it efficiently introduces oxygen-containing functional groups onto the graphite surface while being relatively simple and scalable. In the next step, the Fe3O4-supported N-Asparagine-grafted GO was synthesized through a stepwise process: (i) covalent modification of GO with N-Asparagine, and (ii) magnetization of Asparagine-functionalized GO.

Firstly, modification of GO is initiated by mixing the 0.6 g of the obtained GO with 120 mL of thionyl chloride and stirring for 24 h at 70 °C under an inert atmosphere (Ar), resulting in the acyl-chlorination of GO. Then, it was separated from the reaction mixture through centrifugation, washed three times with tetrahydrofuran (THF) to remove impurities, and dried in a vacuum oven to obtain a solid residue. In the next step, the acyl-chlorinated GO was mixed with 0.3 g Asparagine and refluxed at 120 °C for 72 h beneath argon to graft N-Asparagine on the GO structure. Eventually, the dark solid GO-N-(Asparagine) was obtained after three times washing with deionized water.

Secondly, in order to magnetization process, the resultant GO-N-Asparagine was magnetized with the Fe3O4 according to the Kassaee et al. method20. To achieve this goal, FeCl2·4H2O and FeCl3·6H2O were co-precipitated in water with a molar ratio of 2:1, in the presence of GO-N-Asparagine, as detailed in the following. The process was initiated after sonication (2200 ETH-SONICA ultrasound cleaner) of 0.02 g of GO-N-Asparagine with a frequency of 45 kHz for 25 min in 20 mL of deionized water. Then, a 25 mL aqueous solution of FeCl3 (0.4 g) and FeCl2 (0.15 g) was added to the mixture. The pH was raised to 11 with the dropwise addition of ammonia, and stirred at 75 °C for 30 min. After cooling to ambient temperature, centrifugation removed the precipitate, which was then repeatedly washed with deionized water. The final step involved drying at 75 °C, yielding the pure Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine) nanomagnetic composite.

The synthesis of (dihydropyrano [3,2‑c] chromen‑2‑one) derivatives

The obtained Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine) nanomagnetic composite can catalyse the synthesis process of dihydropyrano [3,2‑c] chromen‑2‑one derivatives, as detailed in the following. The 0.01 g of the obtained catalyst Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine) was added to the 5 mL of aqueous mixture comprising aldehyde (1mmol), malononitrile (0.08 g), and 4-hydroxycoumarin (0.16 g). The advancement of the reactions was tracked using thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on Silica Gel PolyGram SIL G/UV 254 plates. After refluxing the mixture for a certain period (as indicated in Table S2) and determining the completion of the reaction by TLC, it was diluted with 5 mL of hot ethanol while stirring for 10 min. The magnetic properties of the synthesized catalyst make it easy to work with and facilitate separation from the reactive mixture. After separating the catalyst, the remaining mixture was diluted with 50 mL of deionized water while vigorously stirring. The synthesized derivatives were acquired through filtration of the mixture, followed by drying and recrystallization of the remaining product. The identities of the resulting products (4a–i) were determined by analyzing their physical properties and spectroscopic data, including FT-IR, 1H NMR, and 13C NMR spectra (Supplementary material).

The synthesis of (1,4-dihydropyrano [2,3-c] pyrazole) derivatives

The given reaction procedure involved the preparation of a 5 mL aqueous mixture containing aldehyde (1 mmol), malononitrile (66 mg), and 3-methyl-1-phenyl-1 H-pyrazol-5(4 H)-one (0.174 g). The 0.01 g Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine) synthesized nanocatalyst was then added to the mixture, which was stirred under reflux for a specific duration as indicated in Table S3. TLC was used to monitor the progression of the reaction. After refluxing the mixture for a certain period (as indicated in Table S3) and determining the completion of the reaction by TLC, it was diluted with 15 mL of hot ethanol while stirring for 5 min. After separating the catalyst from the mixture with an external magnet, the remaining mixture was evaporated, leaving behind the complex. This product was further purified through re-crystallization using absolute ethanol. The synthesized products (5a–h), identified as known compounds, underwent different characterizations, including FT-IR, 1H NMR, and 13C NMR spectra (Supplementary material). The obtained data were then compared with the corresponding information in Table 1.

Characterization

The newly synthesized nanocatalyst was characterized using a comprehensive suite of analytical techniques to provide a thorough understanding of its structural and functional attributes. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) (NICOLET IZ10, Thermo Scientific, USA) spectroscopy served as a primary tool for elucidating the specific functional groups present within the synthesized catalyst and its derivatives, while also identifying the covalent bonds that contribute to its molecular structure. Raman analysis was conducted using a Thermo Fisher Scientific DXR Raman microscope. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Tescan model: Mira 3) was employed for a detailed examination of the morphology and surface characteristics of the specimens. Energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis was conducted using a VG ESCALAB-200R spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Evanston, IL, USA), equipped with a hemispherical electron analyzer for X-ray detection. This technique facilitated an elemental composition analysis, offering valuable insights into the distribution and concentration of individual elements within the nanocatalyst.

In addition, a thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), a thermogravimetric analyzer Q500 (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA) instrument covering temperatures from 0 to 800 °C was used for TGA under a nitrogen flow. Overall, the application of these analytical techniques provided a multifaceted characterization of the newly synthesized nanocatalyst, encompassing its structural, functional, morphological, and elemental properties, thereby laying a solid foundation for the analysis of the results derived from the computational method and also its potential applications in catalytic processes. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analyses (BRUKER spectrometers 90, 300, and 400 MHz) played a pivotal role in the comprehensive characterization of all samples, which were recorded in CDCl3 or DMSO-d6 using Me4Si as an internal standard (supplementary file).

Computational method

DFT analysis is a widely employed scientific approach utilized to optimize molecules to their lowest ground state energy while also probing their electronic propertie21,22. In our current research, the B3LYP functional has been chosen as it is a coherent method for determining ground-state geometries of a diverse array of molecules. The B3LYP/6-31G** level has been implemented using the Orca package to conduct ground-state geometry optimizations. This involves refining the molecular structures to their most energetically stable configurations. Furthermore, the electronic characteristics of the molecules under investigation are calculated, providing valuable insights into their electronic behavior. The application of DFT analysis with the specified computational settings using the Orca package ensures a comprehensive exploration of molecular structures and electronic features in our research endeavors23.

Results and discussion

Synthesis procedures of Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine)

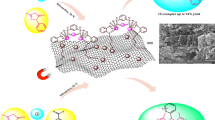

Figure 2 illustrates the modified procedure employed for synthesizing the Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine) nanocomposite catalyst. The principle of the synthesis of the nanocatalyst was based on the following steps; (1) fabrication of GO nanosheets using the modified Hummers method; (2) acyl-chlorination of GO using thionyl chloride; (3) functionalization with L-asparagine through a simple covalent modification process; and (4) magnetization through the co-precipitation of Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions made by FeCl2.4H2O and FeCl3.6H2O, in the presence of GO-N-(Asparagine).

Characterization

The FTIR spectra of the GO and Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine) are illustrated in Fig. 3a. The FTIR analysis revealed distinctive features in the spectra of GO and the synthesized nanocatalyst. For GO, the O-H stretching vibration of the carboxylic acid is not visible due to the low oxygen percentage of GO in the range of 2500–3600 cm-1. However, peaks at 1722, 1570, and 1020 cm-1 in the GO spectrum were assigned to the stretching vibrations of carbonyl (C = O), carbon-carbon double bonds (C = C), in the GO framework, and C–O bonds, respectively1. The characteristic peak at 1260 cm-1 in pure GO spectra was attributed to the asymmetric stretch of the C-O-C bonds, which signifies the presence of epoxide functional groups24. In the spectrum of the Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine) nanostructure, stretching vibrations of the Fe–O bond could be seen at 590 and 633 cm-1 (Fig. 3a). The peak at 1209 cm-1 was assigned to the vibration of the amino C–N bond formed during the amino introduction of GO films with asparagine. Furthermore, the distinctive stretching vibrations at 2850 and 3544 cm-1 in the Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine) spectra are ascribed to the N-H bond overlain by the O–H bond. Notably, the carboxylic group’s stretching frequency, which is at 1718 cm-1 for GO in the Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine)3,25. These findings signify the successful grafting of asparagine onto GO, further supported by the presence of the Fe3O4 group.

The successful grafting of asparagine on the surface of GO, as indicated by the FTIR spectra, significantly enhances the catalytic properties of the material by introducing reactive functional groups such as amine. These groups facilitate improved interaction with reactants, thereby increasing the catalytic efficiency26. The incorporation of Fe3O4 further contributes to the catalyst’s magnetic properties, allowing for easy recovery and enhancing its practical application in heterogeneous catalysis1. The combination of these modifications not only improves the material’s catalytic activity but also promotes its stability, recyclability, and environmental sustainability, making it an effective and green nanocatalyst for the synthesis of 5-oxo-dihydropyrano[3,2-c]chromenes as well as dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole derivatives.

The Raman spectra of GO, GO-N-(Asparagine), and Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine) are depicted in Fig. 3b. In the Raman spectra of GO, the D band and G band appear at 1300 and 1556 cm-1, respectively. Additionally, in the Raman spectra of GO-N-(Asparagine), the D and G bands appear at 1292 and 1544 cm-1, respectively. Raman spectra of carbonaceous materials typically feature three main bands: The D-band, G-band, and 2D-band. The D-band is attributed to carbon with defects, while the G-band corresponds to graphitic carbon defects27.

Furthermore, the Raman spectrum of Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine) shows the presence of five active peaks at wave numbers below 1000 cm-1, including 129, 195, 312, 408, and 608 cm-1 which are the characteristic Raman signature of Fe3O4. The observation that the G band (1554 cm-1) in the Raman spectrum of Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine) is shorter than that of GO further confirms the successful fabrication of the nanocatalyst. Additionally, a lower D band (1238 cm-1) is observed compared to the GO sample due to the increased degree of disorder caused by the formation of magnetite particles on the surfaces of the GO layers28,29.

The TGA diagrams of the synthesized GO, GO-N-(Asparagine), and Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine) are depicted in Fig. 3c. Based on the TGA diagram of GO, three weight loss stages are observable. The first stage of weight loss in the GO diagram occurred in the range of 100–110 °C due to the evaporation of water molecules in the synthesized GO sample, resulting in a weight loss of approximately 10% by weight. The second stage of weight loss, one of the most significant weight losses in the GO TGA diagram, took place in the temperature range between 190 and 200 °C, attributed to the decomposition of oxygen-containing functional groups, including hydroxyl, epoxy, and carboxyl groups. The recorded weight loss for the second stage was approximately 20 wt%. Finally, the last stage of weight loss in the GO diagram occurred in the temperature range of 250 to 600 °C, following the weight loss of the second stage and attributed to the decomposition of oxygen-containing functional groups. Its weight loss amount was also about 22 wt%.

Observing the TGA diagram of GO-N-(Asparagine), three distinct weight loss stages are evident. The initial stage of weight loss in the GO-N-(Asparagine) diagram took place within the temperature range of 98–110 °C, which was related to the evaporation of water molecules from the fabricated GO-N-(Asparagine) sample, resulting in a weight loss of approximately 10% by weight. The second stage of weight loss, occurring between 180 and 250 °C, represents one of the most substantial weight reductions in the GO TGA plot. This stage is attributed to the decomposition of oxygen-containing functional groups in GO and Asparagine functional groups, including amide, amine, and carboxylic acid, with a recorded weight loss of approximately 20%. Finally, the last stage of weight loss in the GO-N-(Asparagine) TGA, taking place between 250 and 700 °C, follows the weight loss observed in the second stage, with the weight loss for this stage also approximately 22 wt%. TGA of Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine) indicated a 5% decrease in weight at 100 °C, followed by a 20% decrease in the 150–750 °C range. This latter loss was attributed to the decomposition of oxygen-containing functional groups, amide, and amine of GO-N-(Asparagine). The remaining weight at 750 °C was approximately 15%. The disparity between the TGA curves of the produced materials and the TGA results confirms the successful synthesis of GO, GO-N-(Asparagine), and Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine)30.

The SEM analysis served as a pivotal tool for a comprehensive examination of the morphology and size distribution of GO. The SEM images presented in Fig. 4a reveal that GO is composed of thin sheets that are randomly aggregated and wrinkled, closely interacting with one another to form disordered solids1. Contrastingly, the SEM image of the Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine), presented in Fig. 4b, displayed a distinct morphology. In comparison to the relatively smooth surface of GO, the Fe3O4 nanoparticles added to GO appeared as bright dots, which were evenly distributed across the surface of the Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine)20. As depicted in Fig. 4c and Table S1, the EDX and mapping analysis reveal the presence of carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, and iron, providing evidence of the successful grafting of GO with asparagine and the incorporation of Fe3O4. This underscores the integrity and composition of the synthesized nanocatalyst, affirming the effectiveness of the employed synthesis process.

Catalytic activity

The performance assessment of the engineered Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine) nanocatalysts as a heterogeneous catalyst was conducted by subjecting them to testing in the synthesis of 2-amino-3-cyano and 5-oxodihydropyrano [3,2-c] chromenes as well as dihydropyrano [2,3-c] pyrazole derivatives. The procedure entailed the execution of multi-component one-pot cyclization reactions involving malononitrile, aromatic aldehyde, and 4-hydroxycoumarin/3-methyl-1-phenyl-1 H-pyrazol-5(4 H)-one, as exemplified in Fig. 1.

Initially, an experimental procedure was conducted to evaluate the viability of product formation and reaction conditions. This involved utilizing 4-nitrobenzaldehyde, malononitrile, and 4-hydroxycoumarin, and the outcomes were meticulously documented in Fig. S1 and Table S2. Subsequently, various solvents, catalyst loadings, and temperatures were meticulously fine-tuned. To examine the impact of the solvent on the reaction, the reaction was carried out with different solvents, namely H2O, EtOH, CH3CN, and THF, while maintaining a consistent amount (20 mg) of catalyst at ambient temperature. Based on the findings presented in Table S2, the optimal outcomes in terms of reaction rate and yield of the products 2-amino-5-oxo-4-phenyl-4 H,5 H-pyrano[3,2-c]chromene-3-carbonitrile were observed when the reaction was executed in EtOH solvent with a catalyst loading of 20 mg at ambient temperature (entry 2). To corroborate the significance of the Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine) catalyst in the reaction, a control experiment was conducted in the absence of the catalyst, resulting in negligible formation of the desired product (entry 14).

The experiment employed Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine) as a catalyst to investigate the reaction between 4-nitrobenzaldehyde, malononitrile, and 3-methyl-1-phenyl-1 H-pyrazol-5(4 H)-one (Fig. S2 and Table S3). Various factors, such as temperature, catalyst loading, and solvents (H2O, EtOH, CH3CN, and THF), were examined to determine their influence on the reaction. Analysis of the data presented in Table S3 demonstrated that the optimal conditions for achieving the highest yield and rate of the product dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole were conducting the reaction at room temperature in EtOH solvent with a catalyst loading of 20 mg (entry 2). Furthermore, the catalytic activity of Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine) was confirmed by conducting the reaction without the catalyst, which resulted in no detectable amount of the product even after an extended reaction period (entry 14).

In the next step, after optimizing reaction conditions such as temperature, solvent type, catalyst amount, and time, the synthesis reaction of products was investigated under optimal reaction conditions using different derivatives of aldehydes (Figs. S3 and S4). The results of the experimental tests were summarized in Tables S4 and S5 and indicated that all reactions, regardless of the nature of the derivatives, were carried out with high efficiency and suitable timing to synthesize the products. The obtained results demonstrate that aldehydes, whether substituted with electron-donating or electron-withdrawing groups react smoothly to afford desired products (Tables S4 and S5). Table 1 presents an overview of the experimental data obtained from this protocol, which is compared to data reported by other groups in the catalytic synthesis of 5-oxo-dihydropyrano[3,2-c]chromenes and dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole derivatives. This comparison clarified that Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine) is a more efficient, environmentally friendly, and straightforward heterogeneous catalyst compared to other catalysts.

This phenomenon can be attributed to the remarkable catalytic efficiency of the graphene oxide-supported catalyst, which features highly active sites, strong magnetic properties, and a diverse range of functional groups such as epoxy, hydroxyl, carboxyl, and asparagine. These functional groups exhibit dual Lewis acid and Lewis base behaviors, facilitating the activation of aromatic aldehydes irrespective of the nature of their substituent groups.

Catalytic reaction mechanism

Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine) is a multifunctional catalyst for the synthesis of 2-amino-4-aryl-7,7-dimethyl-5-oxo-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4 H-chromene-3-carbonitrile and 1,4-dihydropyrano[2,3‐c]pyrazole derivatives. Its functions include catalysis, support for GO, Lewis acid-base interactions, reaction intermediate stabilization, magnetic separation for catalyst recovery, improved dispersion in reaction media, and the introduction of specific functional groups to influence reaction pathways. The composite material has synergistic effects, leveraging its magnetic properties, large surface area, and functional groups to assist with the targeted synthesis process.

In the first stage possible mechanism, the catalyst Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine), due to the presence of nitrogen with free electron pairs in the Asparagine, acts as a Lewis acid, facilitating proton abstraction from malononitrile (Fig. 5). In the subsequent step, the reaction between the aldehyde and the malononitrile anion formed in the previous stage takes place, leading to the formation of an intermediate (I) (α-cyanocinnamonitrile). Following this, the asparagine functional group attached to the Fe3O4@GO induces the formation of an enol form resulting from the enolization of dimedone. After the formation of the enol nucleophile, an increasing nucleophilic addition reaction occurs between the enol form derived from 4-hydroxy-2 H-chromen-2-one and the intermediate (I), resulting in the formation of an intermediate (II). The intermediate (II) is incorporated into the intramolecular cycle by the constructed catalyst in the molecular interior, yielding the final product 4 H-chromenes 4a–h1.

Figure 6 depicts the synthesis mechanism of 1,4-dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole derivatives using a three-component reaction between malononitrile, 3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazolin-5-one, and aldehyde in the presence of catalyst Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine). In the first stage of this reaction, the presence of asparagine groups on GO lead to deprotonation from malononitrile, resulting in the formation of a malononitrile anion. In the subsequent stage, the formed anion acts as a nucleophile, participating in an increasing nucleophilic reaction with the targeted aldehyde, forming an intermediate (I). It is worth noting that the presence of the protonated catalyst resulting from the reaction with malononitrile facilitates the reaction between the aldehyde and enol malononitrile. The intermediate (α-cyanocinnamonitrile) in the previous stage reacts with the enolized compound from 5-methyl-2-phenyl-2,4-dihydro-3 H-pyrazol-3-one, giving rise to intermediate (II). In the last stage of the mechanism, the intermediate intermediate (II) enters a cyclization loop between molecules in the presence of the protonated catalyst, leading to the synthesis of products 5a-h3.

Catalyst recyclability

The study investigated how the catalytic performance of Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine) changed concerning the yield across multiple reaction cycles, as depicted in Fig. S5. The catalyst’s recyclability was examined for the pattern reaction, involving 4-nitrobenzaldehyde, malononitrile, and 4-hydroxy-2 H-chromen-2-one. Upon reaction completion, the catalyst could be effortlessly isolated from the reaction mixture with an external magnet. Following the catalyst’s separation, it was washed with a hot ethanol solution. Subsequently, through several cycles, the catalyst demonstrated effective and recyclable catalytic activity in the reaction environment. It was found that using the catalyst in consecutive reactions resulted in only a minor decrease in performance. These findings suggest that the synthesized catalyst could function as a green and separable catalyst in another heterocycle synthesis.

Computational results

The highest occupied and lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals (HOMOs and LUMOs) of all synthesized molecules are calculated by DFT simulations.

The energies of FMOs, such as EHOMO and ELUMO, and HOMO-LUMO energy gaps (Eg), are the key parameters to examine the electronic properties of molecules. The calculated EHOMO, ELUMO, and HOMO-LUMO energy gaps of all synthesized molecules are shown in Table 2.

The assessment of various molecular properties presented in the tables reveals distinct trends and variations across different compounds labelled 4a, 4b, and 5 h in Table S3 and Table S4. Notably, the EHOMO and the ELUMO energies showcase intriguing disparities. For instance, compounds 4b and 5c boast the highest EHOMO values at − 6.378 and − 6.193 eV, while compounds 4c and 5e exhibit the lowest EHOMO values at − 5.767 and − 5.670 eV, respectively. The presence of various functional groups in organic compounds can affect EHOMO. Compounds 4e and 5e have the lowest ELUMO (− 1.896 and − 0.712 eV), while compounds 4b and 5 g have the highest ELUMO (− 2.375 and − 2.567 eV). The presence and type of functional groups in a molecule can influence ELUMO. In the case of compounds 4e and 5e, electron-donating groups such as methyl and methoxy typically reduce ELUMO, whereas in compounds 4b and 5g, electron-withdrawing groups such as nitro increase it.

In organic compounds, the Eg is the difference between the HOMO and the lowest LUMO. This parameter is critical for understanding the electronic structure, reactivity, and other properties of organic molecules. The interpretation of a compound with a higher Eg is context-dependent. In some cases, a higher Eg may indicate lower reactivity, implying a higher energy requirement for electronic transitions and possibly increased stability. However, the interpretation varies depending on the field of study; in pharmaceuticals, a higher Eg can have subtle effects on both reactivity and biological activity. For example, compounds 4c and 5g have the lowest Eg with a value of 3.870 and 3.227, compared to the highest Eg found in compounds 4d and 5b at 4.141 and 5.160.

Furthermore, the vertical ionization energy (IP) (formula 1) and vertical electron affinity (EA) (formula 2) provide insights into the electron behaviour of these molecules. The IP is the amount of energy required to remove an electron from a single, gaseous atom or molecule in its ground state. The highest IP indicates that electrons in the compound are tightly bound, making it less likely to donate electrons readily. In contrast, the lowest IP indicates that electrons are loosely bound, making the compound more reactive in terms of electron donation. Compounds 4b and 5c exhibit the highest IP at 6.378 and 6.193, while compounds 4c and 5e display the lowest IP at 5.767 and 5.67, respectively. Functional groups influence a molecule’s IP. In compounds 4b and 5c, the presence of an electron-withdrawing group (EWG), such as nitro, boosts ionisation energy by reducing electron density. In contrast, the presence of electron-donating groups (EDG) such as hydroxyl and methoxy groups in compounds 4b and 5c reduces ionisation energy by increasing electron density. Conversely, compounds 4b and 5g show the highest EA at 2.375 and 2.567, while the lowest EA is evident in compounds 4e and 5e at 1.896 and 0.712.

The chemical hardness (η) (formula 4), representing the gap between ELUMO and EHOMO, is most pronounced in compounds 4d and 5b at (2.071 and 2.58), whereas compounds 4c and 5g have the lowest η at (1.935 and 1.614). The chemical hardness of a molecule, which measures its resistance to changes in electron density, is influenced by the functional groups present. The EWG groups, such as nitro (NO2) groups, are known to increase chemical hardness by stabilising electron density. In contrast, the EDG groups, such as OH groups, frequently reduce η by increasing electron density.

The chemical potential (µ), calculated as the average of IP and EA energies (formula 5), is highest in compounds 4b and 5c at (− 4.377 and − 4.252) and lowest in compounds 4c and 5e at (− 3.83 and 3.191). The softness (S) (formula 6), a measure related to hardness, reaches its peak in compounds 4c and 5g at 0.258 and 0.31, while the lowest softness is observed in compounds 4d and 5a at 0.241 and 0.194. Electronegativity (χ) (formula 7), calculated as the average of IP and EA energies, is highest in compounds 4b and 5c at (4.377 and 4.252) and lowest in compounds 4c and 5e at (3.832 and 3.191). Lastly, the electrophilicity index (ω) (formula 8), derived from the chemical potential and hardness, is highest in compounds 4b and 5g at (4.785 and 5.416), and the lowest electrophilicity is found in compounds 4c and 5e at (3.734 and 2.054).

Evaluating global chemical reactivity descriptors (GCRD) holds significant importance in gauging the activity of a molecule. The utilization of HOMO and LUMO energies provides a versatile approach to estimating various GCRD characteristics, including but not limited to electronegativity (χ), molecular softness (S), electrophilicity index (ω), chemical potential (µ), and chemical hardness (η). The comprehensive analysis of these descriptors through the examination of HOMO and LUMO energies enables a deeper understanding of the molecular behaviour and responsiveness, thereby facilitating a more insightful assessment of its overall activity. The IP (formula 1) and EA (formula 2) can be determined by utilizing EHOMO and ELUMO as follows36:

The following formula can be utilized as an estimate for absolute hardness36:

The chemical hardness of the molecule can be defined by the determination of the gap between the HOMO and LUMO orbitals as below36:

The electronic chemical potential (µ) of a molecule is calculated by the below equation36:

Molecular softness can be determined through the below equation36:

The molecular electronegativity can be calculated by the below equation36:

The molecular electrophilicity index can be calculated by the below equation36:

Apart from the mentioned parameters, the assessment also extended to determining the strength of the molecules’ holes and electron injection barriers, denoted as HIE and EIE, respectively, at the Al and Au electrodes, which these values were reported in Table 2. The calculation of the molecules’ EIE involves subtracting the negative value of the LUMO energy from the work function as − ELUMO− (− W), while the HIE is calculated by subtracting the work function from the negative value of the HOMO energy as − W−(− EHOMO), where W represents the work function of the respective electrode, with values of 5.1 eV for Au and 4.08 eV for Al21.

In general, the HOMO density tends to localize in regions of the molecule where lone pairs of electrons, pi (π) bonds, or functional groups capable of donating electrons are present. These regions typically include heteroatoms such as nitrogen, or oxygen, as well as double or triple bonds and aromatic rings. Conversely, the LUMO density tends to localize in regions where vacant orbitals capable of accepting electrons are found. These regions often include π* anti-bonding orbitals present in double or triple bonds, as well as areas near electronegative atoms or functional groups capable of withdrawing electron density. As depicted in Fig. 7, in all derivatives of 5-oxo-dihydropyrano[3,2-c]chromenes (4a-4i), the HOMO density primarily resides on the amine (NH2) and carbonitrile (–C ≡ N) groups, while the LUMO density predominantly distributes across the chroman-2-one ring. Additionally, in the case of dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole derivatives (5a-5 h), the HOMO density mainly concentrates on the amine (NH2) and carbonitrile (–C ≡ N) groups, and the pyrazole ring, particularly on the N-N bond, while the LUMO density is mainly dispersed over the phenyl, pyrazole, and 1,4-dihydropyrano rings.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the novel Fe3O4@GO-N-(Asparagine) has been successfully fabricated and fully characterized via several analytical techniques. The catalyst’s potential for sustainable industrial and laboratory applications is highlighted by its effectiveness, environmental friendliness, and simplicity of use, including the ability for easy separation and reuse. The fabricated novel catalyst supports the increasing need for ecologically friendly methods in organic synthesis by providing high yields, reduced reaction times, and a green methodology. Additionally, the findings from DFT calculations combined with the catalyst’s versatility in a wide range of organic reactions develop novel potential for its application in a variety of chemical transformations. According to DFT calculations, the EHOMO and ELUMO were raised by electron-withdrawing groups, including nitro, and decreased by electron-donating groups such as hydroxyl and methyl.

Data availability

The data for this study is available from the corresponding author upon on a reasonable request and online from Zenodo repository at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12625167.

References

Khaleghi-Abbasabadi, M. & Azarifar, D. Magnetic Fe3O4-supported sulfonic acid-functionalized graphene oxide (Fe3O4@GO-naphthalene-SO3H): a novel and recyclable nanocatalyst for green one-pot synthesis of 5-oxo-dihydropyrano[3,2-c]chromenes and 2-amino-3-cyano-1,4,5,6-tetrahydropyrano[3,2-c]quinolin-5-ones. Res. Chem. Intermed. 45, 2095–2118 (2019).

Flores-Reyes, J. C., Cotlame-Salinas, V. D. C., Ibarra, I. A. & González-Zamora, E. Islas-Jácome, A. Pseudo-multicomponent reactions. RSC Adv. 13, 16091–16125 (2023).

Azarifar, D. & Khaleghi-Abbasabadi, M. Fe3O4-supported N-pyridin-4-amine-grafted graphene oxide as efficient and magnetically separable novel nanocatalyst for green synthesis of 4H-chromenes and dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole derivatives in water. Res. Chem. Intermed. 45, 199–222 (2019).

Su, C. & Loh, K. P. Carbocatalysts: graphene oxide and its derivatives. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 2275–2285 (2013).

Dai, L., Chang, D. W., Baek, J. B. & Lu, W. Carbon nanomaterials for advanced energy conversion and storage. Small 8, 1130–1166 (2012).

Gao, F., Zhang, S., Lv, Q. & Yu, B. Recent advances in graphene oxide catalyzed organic transformations. Chin. Chem. Lett. 33, 2354–2362 (2022).

He, H., Klinowski, J., Forster, M. & Lerf, A. A new structural model for graphite oxide. Chem. Phys. Lett. 287, 53–56 (1998).

Veisi, H. et al. Recent advances in the application of magnetic nanocatalysts in multicomponent reactions. RSC Adv. 13, 20530–20556 (2023).

Wen, Z., Yang, K., Deng, J. & Chen, L. Advancements in the Preparation of 4 H-chromenes: an overview. Adv. Synth. Catal. 365, 1290–1331 (2023).

Costa, M., Dias, T. A., Brito, A. & Proença, F. Biological importance of structurally diversified Chromenes. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 123, 487–507 (2016).

Sabitha, G., Arundhathi, K., Sudhakar, K., Sastry, B. S. & Yadav, J. S. Cerium(III) chloride–catalyzed one-pot synthesis of tetrahydrobenzo[b]pyrans. Synth. Commun. 39, 433–442 (2009).

Guo, S., Wang, S. & Li, J. D., L -Proline‐catalyzed one‐pot synthesis of Pyrans and pyrano[2,3‐c]pyrazole derivatives by a grinding method under solvent‐free conditions. Synth. Commun. 37, 2111–2120 (2007).

Sikandar, S. & Zahoor, A. F. Synthesis of pyrano[2,3-c]pyrazoles: A review. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 58, 685–705 (2021).

Vasuki, G. & Kumaravel, K. Rapid four-component reactions in water: synthesis of Pyranopyrazoles. Tetrahedron Lett. 49, 5636–5638 (2008).

Balaskar, R. S. et al. Greener approach towards the facile synthesis of 1,4-dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazol-5-yl cyanide derivatives at room temperature. Chin. Chem. Lett. 21, 1175–1179 (2010).

Azarifar, D., Tadayoni, M. & Ghaemi, M. γ-Fe 2 O 3 @cu 3 Al‐LDH‐TUD as a new amphoteric, highly efficient and recyclable heterogeneous catalyst for the solvent‐free synthesis of dihydropyrano[3,2‐ c ]pyrazoles and dihydropyrano[3,2‐ c ]chromens. Appl. Organom Chemis. 32, e4293 (2018).

Gogoi, S. & Zhao, C. G. Organocatalyzed enantioselective synthesis of 6-amino-5-cyanodihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazoles. Tetrahedron Lett. 50, 2252–2255 (2009).

Khaleghi Abbasabadi, M., Azarifar, D. & Esmaili Zand, H. R. Sulfonic acid-functionalized Fe3O4-supported magnetized graphene oxide quantum Dots: A novel organic-inorganic nanocomposite as an efficient and recyclable nanocatalyst for the synthesis of dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole and 4H-chromene derivatives. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 34, e6004 (2020).

Hummers, W. S. & Offeman, R. E. Preparation of graphitic oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 80, 1339–1339 (1958).

Kassaee, M. Z., Motamedi, E. & Majdi, M. Magnetic Fe3O4-graphene oxide/polystyrene: fabrication and characterization of a promising nanocomposite. Chem. Eng. J. 172, 540–549 (2011).

Jin, R. Y. et al. Design, synthesis, antitumor activity and theoretical calculation of novel PI3Ka inhibitors. Bioorg. Chem. 98, 103737 (2020).

Fouda, A. M., Irfan, A., Al-Sehemi, A. G. & El-Agrody, A. M. Synthesis, characterization, anti-proliferative activity and DFT study of 1H-benzo[f]chromene-2-carbothioamide derivatives. J. Mol. Struct. 1240, 130542 (2021).

Vogiatzis, K. D. et al. Computational approach to molecular catalysis by 3d transition metals: challenges and opportunities. Chem. Rev. 119, 2453–2523 (2019).

Chen, G. et al. Preparation of sulfonic-functionalized graphene oxide as ion-exchange material and its application into electrochemiluminescence analysis. Biosens. Bioelectron. 26, 3136–3141 (2011).

Khaleghi Abbasabadi, M. & Azarifar, D. β-Alanine‐functionalized magnetic graphene oxide quantum Dots: an efficient and recyclable heterogeneous basic catalyst for the synthesis of 1 H ‐pyrazolo[1,2‐b]phthalazine‐5,10‐dione and 2,3‐dihydroquinazolin‐4(1 H)‐one derivatives. Appl. Organom Chemis. 34, e5872 (2020).

Rodrigo, E. et al. Reduced graphene oxide supported piperazine in aminocatalysis. Chem. Commun. 50, 6270–6273 (2014).

Shi, P. C. et al. Large-scale production of high-quality graphene sheets by a non-electrified electrochemical exfoliation method. Carbon 126, 507–513 (2018).

Jiang, Y., Jiang, Z. J., Yang, L., Cheng, S. & Liu, M. A high-performance anode for lithium ion batteries: Fe3O4 microspheres encapsulated in Hollow graphene shells. J. Mater. Chem. A. 3, 11847–11856 (2015).

Benjwal, P., Kumar, M., Chamoli, P. & Kar, K. K. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue and adsorption of arsenic(III) by reduced graphene oxide (rGO)–metal oxide (TiO2/Fe3O4) based nanocomposites. RSC Adv. 5, 73249–73260 (2015).

Mahmoudi-Gom Yek, S., Azarifar, D., Khaleghi‐Abbasabadi, M., Keypour, H. & Mahmoudabadi, M. Heterogenized magnetic graphene oxide‐supported N6‐Schiff base Cu (II) complex as an exclusive nanocatalyst for synthesis of new pyrido[2,3‐d ]pyrimidine‐7‐carbonitrile derivatives. Appl. Organom Chemis. 34, e5989 (2020).

Abdolmohammadi, S. & Balalaie, S. Novel and efficient catalysts for the one-pot synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrano[c]chromene derivatives in aqueous media. Tetrahedron Lett. 48, 3299–3303 (2007).

Wang, H. J., Lu, J. & Zhang, Z. H. Highly efficient three-component, one-pot synthesis of dihydropyrano[3,2-c]chromene derivatives. Monatsh Chem. 141, 1107–1112 (2010).

Sinija, P. S. & Sreekumar, K. Facile synthesis of Pyranopyrazoles and 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones by a Ti-grafted polyamidoamine dendritic silica hybrid catalyst via a dual activation route. RSC Adv. 5, 101776–101788 (2015).

Abdollahi-Alibeik, M., Moaddeli, A. & Masoomi, K. BF3 bonded nano Fe3O4 (BF3/MNPs): an efficient magnetically recyclable catalyst for the synthesis of 1,4-dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole derivatives. RSC Adv. 5, 74932–74939 (2015).

Niknam, K., Borazjani, N., Rashidian, R. & Jamali, A. Silica-bonded N-propylpiperazine sodium n-propionate as recyclable catalyst for synthesis of 4H-pyran derivatives. Chin. J. Catal. 34, 2245–2254 (2013).

Fouda, A. M. et al. Synthesis of 1,4-dihydropyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole derivatives and exploring molecular and cytotoxic properties based on DFT and molecular Docking studies. J. Mol. Struct. 1249, 131555 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Bu-Ali Sina University’s Research Council for funding this research. They also express their gratitude to the Technical University of Liberec on Student Grant Competition SGS-2025-3580. In addition, this work was partially funded by MEYS project No. CZ.02.01.01/00/22_008/0004617 (Eco&Stor) and received support from the European Union’s HORIZON EUROPE WIDERA 2021 program under the SURRI project (Grant Agreement No. 101079345).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The following are the specific contributions that each author made to the development of this work: M.K., H.H., and S.K. Conceptualization, M.K., Methodology, and Experimental tests; H.H. Density functional theory calculation; M.K., H.T., and H.H., Writing—Original Draft Preparation; M.K., D.A., H.T., H.H., S.K., B.R, B.B. and D.S. Review and Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khaleghiabbasabadi, M., Azarifar, D., Taghavian, H. et al. Asparagine-modified magnetic graphene oxide as efficient green nanocatalyst for synthesis of chromenes and pyrano pyrazoles derivatives. Sci Rep 15, 17252 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00777-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00777-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Eco-friendly and efficient development of C–C bond via Knoevenagel condensation reaction catalyzed with low-loaded aminoformamidine-functionalized nitrogen doped reduced graphene oxide

Research on Chemical Intermediates (2026)

-

Graphene Oxide-Based Nano Catalysts: A Green Protocol Towards the Synthesis of Heterocyclic Scaffolds

BioNanoScience (2026)

-

SiO₂@Fe3O4@Purine-SO3H: a robust solid acid nanocatalyst for accelerated Biginelli condensation

Research on Chemical Intermediates (2025)