Abstract

An accurate and reliable functional prognosis is vital to stroke patients addressing rehabilitation, to their families, and healthcare providers. This study aimed at developing and validating externally patient-wise prognostic models of the global functional outcome at discharge from intensive inpatient post-acute rehabilitation after stroke, based on a standardized comprehensive multidimensional assessment performed at admission to rehabilitation. Patients addressing intensive inpatient rehabilitation pathways within 30 days from stroke were prospectively enrolled in two consecutive multisite studies. Demographics, description of the event, clinical/functional, and psycho-social data were collected. The outcome of interest was disability in basic daily living activities at discharge, measured by the modified Barthel Index (mBI). Machine learning-based prognostic models were developed, internally cross-validated, and externally validated. Interpretability techniques were applied for the analysis of predictors. 385 patients were considered, 220 (165) for training (external test) sets. A 50.9% (55.8%) of women, 79.5% (80.0%) of ischemic, and a median [interquartile range- IQR] age of 80.0[15.0] (79.0[17.0]) were registered. The Support Vector Machine obtained the best validation performances and a median absolute error [IQR] on discharge mBI estimation of 11.5[15.0] and 9.2[13.0] points on the internal and external testing, respectively. The baseline variables providing the main contributions to the predictions were mBI, motor upper-limb score, age, and cognitive screening score. We achieved a solution to support the formulation of a functional prognosis at intensive rehabilitation admission. The interpretability analysis confirms the relevance of easily collected motor and cognitive dataat admission and of the patient’s age.

Trial registration: Prospectively registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (registration numbers RIPS NCT03866057, STRATEGY NCT05389878).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The transversally recognised goal in stroke care is to reach and deploy a Predictive, Preventive, and Personalised Medicine approach, in the acute, rehabilitative, or chronic setting1,2,3. These objectives need to process enormous quantities of data, partially exploited with conventional approaches4,5. Machine learning (ML)-based approaches, enable the processing of larger quantities of data and the exploration of both linear and non-linear relationships, ultimately leading to a wide variety of research and clinical applications6,7. Some studies have shown an increased diagnostic of ML models in cerebrovascular diseases1 but the actual implementation of these methods in clinical practice seems far from immediate, often due to data reporting heterogeneity and incompleteness8. As to diagnostic neuroimaging, the area of image processing and analysis already experiences machine learning-based applications for daily use in clinical practice such as softwares for imaging reporting, already certified for clinical use in hospitals. Based on clinically validated ML algorithms, they automatically generate a standardised score needed to determine eligibility for thrombectomy9,10.

Machine learning has been also implemented in medical research to identify recovery patterns within the stroke population and to improve long-term outcome prediction in these patients11,12,13. Indeed, data-driven solutions could improve the prediction of rehabilitation outcomes and promote the optimisation of a personalised rehabilitation pathway, providing accurate and interpretable information about the patient’s functional outcome at discharge14,15, and pave the way to the development of clinical decision support tools. However, recent reviews concerning the development of predictive models for post-stroke applications in rehabilitation14,15,16, show that only a limited number provide robust and interpretable solutions: in fact, predictive analyses are mostly provided at a biostatistical level, with limited numbers of prospective studies, and few studies performing an internal, and even less an external validation of the results.

The selection of predictors to be included in the model and the reliability and validity of the selected outcome measures are the most relevant aspects of developing a prognostic solution: most studies investigating the functional prognosis after a stroke consider lesion size and location, clinical variables of the acute phase, and demographics, while less attention is given to the multidimensional functional profile of those addressing rehabilitation14,15,16,17. Indeed, stroke rehabilitation outcomes have indeed been associated with a wide range of features, including health conditions, comorbidities, body functions and structures, activities, participation, and contextual factors18, thus, potential predictors should cover the dimensions of functioning, as identified in the World Health Organization International Classification of Functioning, Disabilities, and Health19.

Another relevant issue concerning the applicability of any prognostic solution to most clinical settings is the feasibility of the assessment protocol in routine clinical practice in a wide variety of contexts20. In these regards, the use of validated and standardised measures for the assessments of patients enforces a sharable methodology toward the implementation of common programs, facilitating the possibility of obtaining a greater sample size and generalisability of the results of the studies21,22. Furthermore, the use of a comprehensive set of predictors and of standardised measures guarantees a higher interpretability of the results. The interpretability of machine learning prognostic solutions, where the user is able to understand and interpret the algorithm output23 is crucial in healthcare. A recent study by Chao et al.24 highlights how the concept of interpretability can be connected to a wide variety of factors, that exceed the feature importance and performance of the predictive models, and include also the modality and measures with which variables are represented. Indeed, reduced use of derived composite measures and indexes24 and the selection of proper and standardised measurements25 can positively affect the success likelihood of a trial and the explainability of its results.

With the aim to identify the predictors of intensive inpatient stroke rehabilitation outcomes, our research group has conducted two consequent prospective studies involving post-acute stroke inpatients addressing multiple Intensive Rehabilitation Units – (IRUs) throughout Italy, that shared an evidence-based rehabilitation pathway26,27. In the first study (Intensive Rehabilitation Post Stroke—RIPS28), the selection of potential predictors included a multidimensional assessment based on recommended measures of clinical and functional patients’ features26,29 and a more extensive assessment including neurophysiological and neurogenetic data. The second study (Stroke Rehabilitation Registry for the systematic assessment of processes and outcomes and the development of data-driven prediction models—STRATEGY30), , adopted only demographics and clinical potential predictors of rehabilitation outcomes. Specifically, in STRATEGY, the measures included those required by the Italian Minimal Assessment Protocol of patients addressing stroke rehabilitation20, developed, with the contribution of the experience and preliminary results of the RIPS study, within the Italian Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, Stroke Section, and the Italian Society of Neurological Rehabilitation, and information on clinical/rehabilitation complexity31.

The aim of this study was to develop, internally test, cross-validate, and externally test a machine learning-based prognostic model based on a comprehensive assessment of patients easily collected in routine clinical practice, and to provide an interpretable solution, through Shapley techniques, to accurately predict intensive inpatient rehabilitation global functional outcome after a stroke.

Methods

Study design and sample

The data used for the analyses in this work were obtained from two observational multi-site studies: RIPS28 and STRATEGY30. Both study protocols were a-priori registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (registration number RIPS: NCT03866057, registration number STRATEGY: NCT05389878) and were submitted and approved by the local ethical committees (RIPS: Florence, 14513; La Spezia, 294/2019; Massa and Fivizzano, 68013/2019; STRATEGY: Florence, 19779_oss). This research weas performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

The inclusion criteria for both studies were the following:

-

Age ≥ 18 years old.

-

First-ever recurrent acute ischemic or haemorrhagic stroke diagnosed clinically and with brain imaging occurred within 30 days from recruitment.

-

First-ever admission to the IRU for the considered stroke.

-

Written informed consent.

Patients with a transitory ischemic attack or those addressed to the severe brain injury high-complexity rehabilitation ward of the IRUs, were also excluded from both studies.

In both studies, the evidence-based integrated rehabilitation pathway27, shared by all IRUs involved in the studies, was developed in line with the requirements of the Italian Health care System and with current recommendations for stroke rehabilitation, based on the SPREAD (Italian Stroke Guidelines) 2011 guidelines32 and the AHA/ASA Stroke rehabilitation guidelines26. All patients were addressed to intensive inpatient rehabilitation from an acute care hospital if presenting a diagnosis of stroke with mild-to-severe disability and need for clinical management. The individual rehabilitation plan was defined by an interdisciplinary team: each patient received at least an average of 3 h of rehabilitation/day, clinical observation and management, nurse management, and physiotherapy. Personalised rehabilitation plans may also incorporate speech/swallowing and/or language and communication and/or other cognitive rehabilitation, occupational therapy, psychological support to patients and family, and advice and training on aids when prescribed according to the team assessment, as well as advice/prescription of home to promote and facilitate home discharge. The individual rehabilitation plan was designed and agreed with patient and/or family within 48 h from admission and collectively revised by the interdisciplinary rehabilitation team at least weekly after admission25,31. Discharge was generally determined by the achievement of the shared outcomes, or when the functional improvement reached a plateau and no further improvement was expected27,33. Further details on the rehabilitation pathway can be found elsewhere28,34.

Measures and model implementation

The time points considered in this study were admission (baseline) and discharge from the rehabilitation stay. The selected outcome was the modified Barthel Index (mBI) total score, collected at discharge.

For what concerns the predictors, all the variables considered were collected at admission to the IRUs. To allow for a comprehensive description of the patients, the variables were selected from the following domains:

-

Demographics.

-

Description of the event.

-

Clinical assessment.

-

Physiotherapic assessment.

-

Psycho-social assessment.

Further detail on the specific independent variables considered is presented in supplementary materials (Table SM1).

As to the model development, the analysis pipeline (Fig. 1) can be summarised in three main steps: dataset conversion, data pre-processing, and development of the machine learning prediction model. Details on the model development are in the Supplemental Method.

The first step, dataset conversion, included the agreement of information between the datasets of the two studies. Discrepancies between the RIPS and STRATEGY assessments concerned the motor, cognitive, and comorbidity assessment. After this process, data pre-processing involved the selection of features, excluding the categorical variables with less than 10 samples in one group and categorical or continuous variables with more than 20% missing data. Patients with missing values on the outcome were also excluded.

Lastly, the model implementation identified the database from RIPS with the training/internal validation set, whilst the database from the STRATEGY study with the test set for external validation. On both sets, statistical analyses (IBM Corp. Released 2020. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp) were conducted to investigate the association of baseline independent variables with the outcome.

The model implementation was performed on Python, using the Scikit-learn library35. Eight different algorithms were considered for mBI estimation, namely the Lasso regularised regression (LASSO), the least-angle regression (LARS), the Huber regression (HUBER), the Orthogonal Matching Pursuit (OMP), k-Nearest Neighbours (kNN), the Support Vector Regression (SVR), Random Forest (RF), and the Classification and Regression Trees (CART). On the training set, an inner 10-fold loop was used to optimise the hyper-parameters of the models, the number of features for forward feature selection, and the kNN imputer for missing data imputation (Table SM2), whilst an external 5-fold loop was employed for internal testing. Lastly, the best-performing algorithm on the validation set was considered for the external validation.

Model performances were assessed by Median Absolute Error (MAE) and absolute error interquartile range (IQR); interpretability analysis was applied using the Shap library36. The results of the interpretability analysis, in terms of predictor contributions on the training set, were provided for each algorithm separately for each external 5-fold loop, as well as aggregated. Both performance metrics and interpretability analyses were performed on the results obtained on the test sets after internal and external validation.

Results

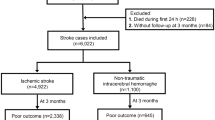

Total numbers of 234 and 217 patients were enrolled in RIPS and STRATEGY (Florence site only) studies, respectively. The selection of records during the pre-processing phase led to the exclusion of 14 enrolled patients not presenting the mBI at discharge (outcome), in RIPS study. In STRATEGY, 52 patients did not present the outcome or were still hospitalised. A final sample of 220 patients for the RIPS study (training set) and 165 patients for the STRATEGY study (test set) was obtained (Fig. 2).

The features to be considered as candidate predictors were selected, involving the domains of functioning of the Minimal Assessment Protocol of Stroke patients20 and the markers of clinical/rehabilitation complexity31 included in both studies. After the statistical screening process on the variables, 4 features from the initial set of 41 were excluded for presenting less than 10 sample for each group (dialysis and tracheostomy) or > 20% missing values (FAI and mFWC). The characteristics of the samples are presented in Table 1.

The results of univariate analyses investigating associations between the selected predictor variables and the outcome are presented in Table SM3.The results on the ML models reported the SVR as the best performing algorithm on the validation set, obtaining a MAE [IQR] of 11.50 [14.00] on the internal test set (Table 2). For this reason, subsequent interpretability and error analyses, as well as external testing, were computed on the model using the SVR algorithm. Figure 3 is reporting scatter plots of the predicted and actual values on the mBI (panels A and C). The resultant RMSE and correlation coefficient for the SVR model were respectively 17.67 and 0.837 for the internal test predictions, 16.59 and 0.796 for the external testing predictions. On the external testing, the SVR obtained a MAE [IQR] of 8.96 [13.64].

Among the features collected at adimission and mostly contributing to the prediction, greater motor capabilities on the upper limbs (motricity section of the Fugl-Meyer Assessment, FMA-M, and Motricity Index, MI, converted), higher functional level on the mBI, higher cognitive abilities (Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA and Mini-Mental State Examination, MMSE converted), lower stroke severity (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, NIHSS), lower comorbidities (Cumulative Index Rating Scale, CIRS and Charlson Comorbidity Index, CCI converted), and younger age were those prediction an higher functional status at discharge (Fig. 4). The same variables were transversally encountered on both the external testing and each outer loop fold on the internal testing. These results were indeed confirmed by the statistical analyses, where the above-mentioned variables were significantly associated with the outcome (p-values < 0.001). Further, even with a lower contribution to the prediction, comorbidities (CIRS and CCI converted), clinical/rehabilitation markers of complexity (venous catheter), and lower limb performance (SPPB) were also selected among the features (Fig. 4).

Contributions of the predictors to the outcome prediction aggregated among each fold. In panels (A–C), bar plots of the global contributions are presented, whilst in panels (B–D), beeswarm plots with patient-wise contributions are presented. The results are presented for the SVR algorithm. In panels (A–D), the results on the test set of the internal and external validation are presented, respectively. MAS Modified Ashworth Scale, mBI Modified Barthel Index, MI Motricity Index, MMSE Mini-Mental State Examination, mRS Modified Rankin Scale, NIHSS National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, SPPB Short Physical Performance Battery, TCT Trunk Control Test, UL Upper Limbs.

Discussion

In this study, we validated a ML model for the prediction of the functional outcome of post-stroke patients after rehabilitation. The methodology adopted was based on a joint clinical and automatic strategy, starting from the design of the assessment protocol and following on model validation and interpretation. The prospective clinical identification of the potential predictors, based on a comprehensive set of easily collected standardised clinical variables20,37, and the definition of the evidence-based rehabilitation pathway pose premises both for the generalisability of this approach and for the interpretability of our results. On the other hand, the use of available technologies enables an optimized information extraction from data, supporting the preservation of larger sample sizes with missing data imputation, selecting relevant information only (forward feature selection), and discovering hidden patterns among the data by algorithms of different nature (SVR, RF, kNN, etc…). Indeed, the application of automatic solutions to a prospective database designed by expert clinical researchers can guarantee the interpretability of the solution developed and its results, promoting an increasing trust, usability, and acceptance of these solutions38.

The outcome of interest was selected on the mBI total score which measures the patients’ ability in basic activities of daily living on a 0-100 score. The mBI is a widely used tool in the clinical, research, and hospital administrative context37,39. The selection of the discharge as the primary outcome timing should also bring some considerations. Some authors might see this as a limitation40, as the discharge, theoretically planned when the patient has reached a plateau in functional improvement, may often be influenced also by local rehabilitation resource constraints. However, outcomes collected at a fixed time point after the stroke can be influenced by factors unrelated to rehabilitation, limiting the possibility to investigate the effects of the prescribed rehabilitation pathway in a real-world context.

Compared to other studies on the prediction of the functional outcome at discharge, in that of Sale et al.41, their model obtained similar performances, with slightly higher RMSE (22.60 points vs. 16.64 and 16.07 for internal and external testing, respectively) and slightly weaker correlation between predicted and actual functional measures values in both (0.75 vs. 0.86/0.81 in our internal/external testing, respectively). Further, the authors used the original Barthel Index (BI)42, whilst we adopted its modified version, the mBI, developed to allow more discriminant levels, quantify the need for help, and provide a more accurate description of the abilities required to classify each score in any single item than the original BI43. König et al.21 also addressed a dichotomized mBI, with a cut-off of 95/100 to identify those who recovered full independence; an a-posteriori dichotomisation of our predictions could be possible as well, but the comparison of the results would inevitably lead to poor performances for our model which was not optimized for the dichotomized case. Indeed, dichotomisation of continuous variables is a widespread use approach in medical research, but it has been argued that it may discard valuable information present in the original data44.

Additionally, from a clinical perspective, predicting functional status at discharge—rather than at a fixed time point—has significant implications for both patients, their families, and healthcare systems. An accurate estimation of the functional level a patient will achieve upon completing evidence-based inpatient rehabilitation provides crucial information for planning post-discharge care, optimizing resource allocation, and facilitating continuity of assistance. While other approaches, such as those from Shin et al.11, based on long-term functional trajectories up to 24 months post-stroke, offer valuable insights for health policy and population-level recovery potential, they do not provide the immediate, patient-specific predictions needed to support early rehabilitation planning and discharge management. Discharge outcomes provide indirect support to the overall effectiveness of the evidence-based rehabilitation pathway, including support to family and carers to facilitate the management of home discharge whenever possible. Indeed, despite old age and the persistency of some degree of disability at discharge, the large majority of our patients returned home (310 patients, Table SM4).

Among the selected predictors, age, mBI, and FMA-M-MI at baseline were those of more relevant contribution to the prediction of the model, in substantial agreement with previous literature. In the study from Harari et al.45, investigating predictors of rehabilitation outcomes in 50 stroke patients admitted to intensive inpatient rehabilitation, the FIM admission score was the main predictor of discharge FIM score. Harari et al.45 show some potential sources of bias, such as the reduced numerosity, the sample heterogeneity (time post-onset from 3 to 181 days). However, the predictive equation for the FIM discharge score explained 76% of their data variance. This study stressed the importance of including a comprehensive set of demographic and clinical information to predict the global functional outcome. Indeed, additional variables with at least 1% of relative importance included the time from stroke onset to admission, age, BMI, race, education, dysphasia, and language impairment. However, the relative importance of these variables was much smaller (10–20%) than that of clinical tests at admission (80–90%) which confirmed to be highly relevant also in our work. In this direction, our results confirmed that also information more rarely collected in rehabilitation studies, such as comorbidities, clinical/rehabilitation markers of complexity (venous catheter), and lower limb performance provide a contribution to our predictive model.

It is worth noting that differences existing between the two databases (Table 1) do not poses serious concerns on the generalization capability of our multifactorial model which preserves its accuracy on the external test set. Despite the presence of several studies on the prediction of post-stroke global functional outcome after inpatient post-acute rehabilitation, to our knowledge only two models were retrospectively developed and validated in the same paper, and further externally validated by other authors in a separate cohort46,47. Scrutinio et al.46 developed a data-driven prediction model over a database of 2180 patients, identifying those who would achieve a motor FIM score of > 61 points at discharge and, with a separate model, those who would achieve a physical independence grade (Functional Independence Staging ≥ 548). Patients were included if they had been admitted within 90 days of onset of an ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. Both models were externally validated by Garcia Rudolph et al.47 in a separate cohort of 710 patients, who also derived a third model, incorporating aphasia and outperforming the previous two. The presented models had all areas under the curve of at least 0.85, thus retaining excellent discrimination. However, both studies were retrospective, reporting minimal information on the rehabilitation pathway, and patients were enrolled up to 90 days after stroke, thus introducing a relevant source of variability, both in terms of case-mix and process (rehabilitation pathway).

Improvements could be further applied to this study, such as the application of additional data pre-processing steps (multiple imputation techniques, or multivariate cell-wise outlier detection) and the validation of our solution on other independent study cohorts. Accuracy might be improved by the inclusion in the analyses of the intercurrent adverse events, as well as of other clinical predictors emerging from the literature, and also of neuroimaging or other instrumental data, provided that they may be easily collected in most rehabilitation settings.

A limitation of our study concerns the conversion procedure among the datasets from the two considered studies (RIPS and STRATEGY) commented on supplementary methods. Conversions were performed following the available normative data, when possible (such as in the case of MoCA and MMSE). For both comorbidity and motricity conversion scores were unavailable: considering the similarity of the outcome measured we simply converted them as a percentage. With regard to motricity, this choice can be questioned, as the two scales (MI and FMA-M) measure somewhat different aspects of motor function. In fact, the MI assesses exclusively muscle strength, whereas the FMA-M assesses the selective control of movements (and thus, partially, also muscular strength), coordination, and reflex activity. Despite these differences, however, a strong correlation between them for both upper and lower limbs has been found49; moreover, the two scales showed fairly similar or even equal effect sizes in clinical trials50,51,52,53,54. Therefore, the error resulting from the conversion method used should be small or negligible.

Finally, part of the period of observation of the two prospective studies occurred during the COVID19 pandemic. However, except for the 2.5 lockdown months when the RIPS study was suspended, the IRUs maintained a similar activity throughout the period of observation and the features of the study cohorts did not differed between previous and current data55,56.

All this acknowledged, our results add relevant information to the current state of the art. Patients were prospectively and systematically enrolled among those addressing intensive inpatient post-stroke rehabilitation and were consistently provided a previously defined evidence-based rehabilitation pathway throughout the involved IRUs. Indeed, the prospective databases used both RIPS and STRATEGY to fulfill the criteria of high quality in prognostic studies57, for all areas defining the risk of bias: participation, attrition, prognostic factor measurement, confounding measurement and account, outcome measurement, and analysis and reporting. Moreover, the number of patients included in our analyses is indeed a considerable effort towards a fully representative selection (85%, Fig. 2). Further, our study systematically considered all post-acute stroke patients accessing inpatient rehabilitation, enabling predictions both for ischemic and haemorrhagic stroke. Finally, different from most ML-driven solutions, we included a comprehensive set of information, such as comorbidity, clinical/rehabilitation complexity, and cognitive function, that may actually impact rehabilitation outcomes31,58, as they did in our analyses.

The high and direct translatability of our approach for stroke rehabilitation prognosis stems from its alignment with current Italian and international scientific society indications19,28,36: the clinical variables that emerged as predictors are recommended and collected worldwide and the rehabilitation pathway was specifically designed according to international and international Stroke rehabilitation guidelines25,31 This poses solid premises for trans-national research-to-clinical applicability of our model in providing a more accurate early functional prognosis and paving the way to personalising the stroke patients’ rehabilitation pathway.

Conclusions

This study obtained the first prospectively collected, externally validated, and explainable ML-based prognostic model to accurately estimate the global functional status of post-acute stroke patients at discharge from intensive inpatient rehabilitation, delivered according to an evidence-based rehabilitation pathway. This solution can support the formulation of functional prognosis at admission of post-acute stroke patients to intensive inpatient post-stroke rehabilitation, fostering a prompt identification of features potentially predicting an unfavourable outcome. The results of the interpretability analysis of the model highlight that a highly accurate prediction can be obtained using a set of easily collected clinical variables which provide a minimal but comprehensive assessment of patients addressing stroke rehabilitation.

Data availability

Data and code are available for research purposes upon request to the authors.

Change history

02 September 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17206-8

References

Fan, Y., Song, Z. & Zhang, M. Emerging frontiers of artificial intelligence and machine learning in ischemic stroke: a comprehensive investigation of state-of-the-art methodologies, clinical applications, and unraveling challenges. EPMA J. 14 (4), 645–661 (2023).

Rincé, G. et al. Impact of an individual personalised rehabilitation program on mobility performance in older-old people. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. Ottobre. 33 (10), 2821–2830 (2021).

Podbielska, H. & Kapalla, M. Predictive, preventive, and personalised medicine: from bench to bedside. In Advances in Predictive, Preventive and Personalised Medicine, vol. 17. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34884-6 (2023).

Bonkhoff, A. K. & Grefkes, C. Precision medicine in stroke: towards personalized outcome predictions using artificial intelligence. Brain 145 (2), 457–475 (2022).

Jung, S. et al. Predicting ischemic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation using machine learning. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed). 27 (3), 80 (2022).

Chakraborty, C., Bhattacharya, M., Pal, S. & Lee, S. S. From machine learning to deep learning: advances of the recent data-driven paradigm shift in medicine and healthcare. Curr. Res. Biotechnol. 7, 100164 (2024).

Chandrabhatla, A. S. et al. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in the diagnosis and management of stroke: a narrative review of united States food and drug Administration-Approved technologies. J. Clin. Med. 12 (11), 3755 (2023).

Wang, W. et al. A systematic review of machine learning models for predicting outcomes of stroke with structured data. PLoS ONE. 15 (6), e0234722 (2020).

Soun, J. E. et al. Artificial intelligence and acute stroke imaging. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 42 (1), 2–11 (2021).

Bonura, A. et al. Smartphone app in stroke management: a narrative updated review. J. Stroke. 24 (3), 323–334 (2022).

Shin, S. et al. Clustering and prediction of long-term functional recovery patterns in first-time stroke patients. Front. Neurol. 14, 1 (2023).

Shurrab, S. et al. Multimodal machine learning for stroke prognosis and diagnosis: A systematic review. IEEE J. Biomedical Health Inf. 28 (11), 6958–6973 (2024).

Abujaber, A. A. et al. Predicting 90-day prognosis for patients with stroke: a machine learning approach. Front. Neurol. 14, 1 (2023).

Zu, W. et al. Machine learning in predicting outcomes for stroke patients following rehabilitation treatment: A systematic review. PLoS ONE. 18 (6), e0287308 (2023).

Chang, M. C. et al. The use of artificial intelligence to predict the prognosis of patients undergoing central nervous system rehabilitation: A narrative review. Healthcare 11 (19), 2687 (2023).

Campagnini, S. et al. Machine learning methods for functional recovery prediction and prognosis in post-stroke rehabilitation: a systematic review. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 19 (1), 54 (2022).

Stinear, C. M., Byblow, W. D. & Ward, S. H. An update on predicting motor recovery after stroke. Ann. Phys. Rehabil Med. 57 (8), 489–498 (2014).

Cecchi, F. et al. Redefining a minimal assessment protocol for stroke rehabilitation: the new Protocollo di Minima per l’ICtus. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 57 (5), 669 (2021).

International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). https://icd.who.int/dev11/l-icf/en (2023).

Cecchi, F. et al. Redefining a minimal assessment protocol for stroke rehabilitation: the new «protocollo Di minima per L’ICtus (PMIC2020). Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil Med. 57 (5), 669–676 (2021).

König, I. R. et al. Predicting long-term outcome after acute ischemic stroke: a simple index works in patients from controlled clinical trials. Stroke 39 (6), 1821–1826 (2008).

de Ridder, I. R. et al. Development and validation of the Dutch stroke score for predicting disability and functional outcome after ischemic stroke: A tool to support efficient discharge planning. Eur. Stroke J. 3 (2), 165–173 (2018).

Baptista, M., Goebel, K. & Henriques, E. Relation between prognostics predictor evaluation metrics and local interpretability SHAP values. Artif. Intell. 306, 103667 (2022).

Chao, Y. S., Wu, C. J., Wu, H. C., McGolrick, D. & Chen, W. C. Interpretable trials: is interpretability a reason why clinical trials fail? Front. Med. 8, 405 (2021).

Khadka, J., Gothwal, V. K., McAlinden, C., Lamoureux, E. L. & Pesudovs, K. The importance of rating scales in measuring patient-reported outcomes. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 10 (1), 80 (2012).

Winstein, C. J. et al. Guidelines for adult stroke rehabilitation and recovery: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American heart association/american stroke association. Stroke 47 (6), e98–169 (2016).

Cecchi, F. et al. Development and implementation of a stroke rehabilitation integrated care pathway in an Italian no profit institution: an observational study. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil Med. 56 (6), 713–724 (2020).

Hakiki, B. et al. Predictors of function, activity, and participation of stroke patients undergoing intensive rehabilitation: a multicenter prospective observational study protocol. Front. Neurol. 12, 632672 (2021).

Lenti, G. et al. Developing a minimum data set for stroke patients assessment: the Protocollo Di minima per L’Ictus (PMIC) as a starting point towards an Italian stroke registry. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil Med. 44 (3), 263–269 (2008).

Chiavilli, M. et al. Design and implementation of a stroke rehabilitation registry for the systematic assessment of processes and outcomes and the development of data-driven prediction models: the STRATEGY study protocol. Front. Neurol. 13, 919353 (2022).

Banchero, A. et al. Indicatori Di processo Esito in riabilitazione. Quad. Dell’Agenzia. 76, 1 (2012).

Inzitari, D. & Carlucci, G. Italian stroke guidelines (SPREAD): evidence and clinical practice. Neurol. Sci. 27 (Suppl 3), S225–S227 (2006).

Accordo, ai sensi dell’articolo 4 del decreto legislativo 28 agosto 1997, n. 281, tra il Governo, le Regioni e le Province autonome di Trento e di Bolzano sul documento concernente «Piano d’indirizzo per la riabilitazione», Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana, Serie Generale n.50 del 02-03-2011 Suppl. Ordinario n. 60. https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2011/03/02/11A02720/sg (2011).

Chao, Y. S. et al. Interpretable trials: is interpretability a reason why clinical trials fail? Front. Med. 8, 405 (2021).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in python. Mach. Learn. Python. 6, 1 (2020).

Shapley, L. S. A value for n-Person games. Contrib. Theory Games. 2, 307–318 (1953).

Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana. Regolamento recante modificazioni e integrazioni al regolamento recante norme concernenti l’aggiornamento della disciplina del flusso informativo sui dimessi dagli istituti di ricovero pubblici e privati. (23G00174) (GU Serie Generale n.272 del 21-11-2023. https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2023/11/21/23G00174/sg (2023).

Moss, L., Corsar, D., Shaw, M., Piper, I. & Hawthorne, C. Demystifying the black box: the importance of interpretability of predictive models in neurocritical care. Neurocrit Care. 37 (Suppl 2), 185–191 (2022).

Wang, Y. C. et al. Comparison of responsiveness of the Barthel index and modified Barthel index in patients with stroke. Disabil. Rehabil. 1, 1–6 (2022).

Stinear, C. Prediction of recovery of motor function after stroke. Lancet Neurol. 9 (12), 1228–1232 (2010).

Sale, P. et al. Predicting motor and cognitive improvement through machine learning algorithm in human subject that underwent a rehabilitation treatment in the early stage of stroke. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 27 (11), 2962–2972 (2018).

Sale, P. et al. Predicting motor and cognitive improvement through machine learning algorithm in human subject that underwent a rehabilitation treatment in the early stage of stroke. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis.. 27 (11), 2962–2972 (2018).

Shah, S., Vanclay, F. & Cooper, B. Improving the sensitivity of the Barthel index for stroke rehabilitation. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 42 (8), 703–709 (1989).

Altman, D. G. & Royston, P. The cost of dichotomising continuous variables. BMJ 332 (7549), 1080 (2006).

Harari, Y., O’Brien, M. K., Lieber, R. L. & Jayaraman, A. Inpatient stroke rehabilitation: prediction of clinical outcomes using a machine-learning approach. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 17 (1), 71 (2020).

Scrutinio, D. et al. Development and validation of a predictive model for functional outcome after stroke rehabilitation. Stroke 48 (12), 3308–3315 (2017).

García-Rudolph, A. et al. Predictive models for independence after stroke rehabilitation: Maugeri external validation and development of a new model. NeuroRehabilitation 49 (3), 415–424 (2021).

Stineman, M. G., Ross, R. N., Fiedler, R., Granger, C. V. & Maislin, G. Functional independence staging: conceptual foundation, face validity, and empirical derivation. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 84 (1), 29–37 (2003).

Kim, T. L. et al. The Korean version of the Fugl-Meyer assessment: reliability and validity evaluation. Ann. Rehabil Med.. 45 (2), 83–98 (2021).

Chang, M. C., Kim, D. Y. & Park, D. H. Enhancement of cortical excitability and lower limb motor function in patients with stroke by transcranial direct current stimulation. Brain Stimul. 8 (3), 561–566 (2015).

Do, J. et al. Effects of high-intensity interval robot-assisted gait training on cardiopulmonary function and walking ability in chronic stroke survivors: A multicenter single-blind randomized controlled trial. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 37 (5), 1309–1319 (2024).

Lee, J. et al. End-effector lower limb robot-assisted gait training effects in subacute stroke patients: A randomized controlled pilot trial. Med. (Baltim). 102 (42), e35568 (2023).

Mazzoleni, S., Battini, E., Crecchi, R., Dario, P. & Posteraro, F. Upper limb robot-assisted therapy in subacute and chronic stroke patients using an innovative end-effector haptic device: A pilot study. NeuroRehabilitation 42 (1), 43–52 (2018).

Mazzoleni, S., Tran, V. D., Dario, P. & Posteraro, F. Effects of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) combined with wrist robot-assisted rehabilitation on motor recovery in subacute stroke patients: a randomized controlled trial. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil Eng. 27 (7), 1458–1466 (2019).

Campagnini, S. et al. Cross-validation of predictive models for functional recovery after post-stroke rehabilitation. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 19 (1), 96 (2022).

Finocchi, A. et al. Multiple imputation integrated to machine learning: predicting post-stroke recovery of ambulation after intensive inpatient rehabilitation. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 25188 (2024).

Hayden, J. A., van der Windt, D. A., Cartwright, J. L., Côté, P. & Bombardier, C. Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann. Intern. Med. 158 (4), 280–286 (2013).

Ruksakulpiwat, S. et al. Associations between diagnosis with stroke, comorbidities, and activity of daily living among older adults in the united States. Chronic Dis. Transl Med. 9 (2), 164–176 (2023).

Acknowledgements

Authors are indebted with Mrs Donata Bardi, Mrs Chiara Castagnoli and Dr Piergiuseppe Liuzzi for their contributions in project management, data acquisition and coding, respectively.

Funding

The study was funded by the Italian Ministry of Health under the “Ricerca Corrente” program and by Regione Toscana under the Bando Ricerca Salute 2018 (TUNE_BEAM project), H14I20000300002.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The contributions of authors of this work are the following: Conceptualisation: A.M., S.C., F.C.; Clinical assessment protocol design: F.C., B.H., A.G., C.M.; Physiotherapy assessment protocol design: S.D., M.B.; Methodology, Data analysis, Software, Visualization: S.C.; Validation, Formal analysis: S.C., A.M.; Investigation: A.S., S.C, M.B.; Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition: A.M., F.C.; Writing - Original draft: S.C., B.H.; Writing - Review & Editing: S.C., A.S., M.B., B.H., A.G., C.M., A.M., F.C.;

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Study protocols were a-priori registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (registration number RIPS: NCT03866057, registration number STRATEGY: NCT05389878) and were submitted and approved by the local ethical committees (RIPS: Florence, 14513; La Spezia, 294/2019; Massa and Fivizzano, 68013/2019; STRATEGY: Florence, 19779_oss). Patients provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Patients provided written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained errors in which two paragraphs were erroneously moved from the ‘Results’ section to the ‘Conclusions’ section. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Campagnini, S., Sodero, A., Baccini, M. et al. Prediction of the functional outcome of intensive inpatient rehabilitation after stroke using machine learning methods. Sci Rep 15, 16083 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00781-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00781-1