Abstract

The cellular mechanisms underlying a greater risk of cardiometabolic disease in adult offspring exposed to maternal obesity are not known. Our prior work found reduced skeletal muscle mitochondrial metabolism and insulin sensitivity in offspring exposed to maternal (m) Western-style diet (WD), even when weaned onto a control diet (CD) in Japanese macaques. Here, we performed multiple comparisons of differentially expressed (DE) genes in skeletal muscle from lean juvenile offspring to test hypotheses specific to (1) the lasting effects of maternal diet composition and/or maternal adiposity on gene expression and (2) the transcriptional response to a chronic postweaning (pw)WD with and without prior exposure to mWD. Overall, we identified maternal (m)WD, and not maternal adiposity, as a principal driver of DE in offspring muscle even years after exposure with few differences observed in patterns of DE between offspring of lean vs. obese mWD dams. Transcriptional response to the pwWD was robust in mCD offspring but blunted by mWD, particularly in males, suggesting a potential priming of gene expression. KEGG enrichment analysis and assessment of top DE genes identified changes in key pathways associated with dysregulated metabolism and RNA processing. We conclude that mWD has a significant and lasting impact on offspring gene expression which likely contributes to observed skeletal muscle insulin resistance and metabolic dysregulation in these offspring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The risk for the development of obesity and cardiometabolic disease, including type 2 diabetes (T2D) in youth is increased by in utero exposure to maternal malnutrition or a maternal calorically dense and high fat diet1,2,3,4. As two thirds of women in the U.S. fall within or above the overweight BMI category5 and with many individuals having limited access to optimal nutrition6,7,8, the consequences and root sources of these developmental exposure(s) represent a substantial risk to the health of our population. Importantly, the pathologic processes that underlie diabetes, insulin resistance, and beta-cell dysfunction, progress more rapidly in youth with T2D than in adults with the disease9,10. These factors, and a poorer response to treatment, result in overall worse glycemic control and an increased risk of early diabetes-related complications including hypertension, microvascular-related diseases, and dyslipidemia in youth with T2D11. Still, the genetic and molecular mechanisms linking early life exposures to the increased incidence of T2D later in life remain a critical gap in knowledge.

Dysregulation of skeletal muscle insulin-signaling and metabolism is a hallmark of insulin resistance and an underlying cause of cardiometabolic diseases and the progression of age-associated dysfunction12. Prior work in our Japanese macaque model of maternal Western-style diet (WD)-induced obesity identified metabolic dysregulation in multiple tissues of fetal, 1- and 3-year old offspring,13,14,15,16,17,18 including reduced insulin-stimulated glucose uptake and decreased oxidative metabolism in skeletal muscles of fetal and juvenile offspring19,20,21. Our results are consistent with findings of persistent dysregulated muscle metabolites including in TCA cycle and amino acids metabolism in offspring exposed to maternal obesity but fed a healthy diet at weaning in a baboon model22 as well as reduced skeletal muscle contractile function, an energy dependent process, in offspring of junk food fed rodents23. Similarly, mitochondrial metabolism and insulin sensitivity in infant mesenchymal stem cells has been shown to correlate with maternal health measures24,25,26. In rodents, metabolic dysfunction in offspring from obese dams persisted across three generationseven when F1 offspring were switched to a healthy diet27. The persistence of these phenotypes with offspring age and across generations suggests durable molecular reprogramming and modifications to the transcriptome due to maternal metabolic health, adiposity and/or diet28.

To better understand the molecular underpinnings of impaired skeletal muscle metabolism in offspring, we sought to determine the impact of maternal diet and adiposity on programming of gene transcription along well-characterized pathways in lean early juvenile offspring. We also examined the effect of a postweaning (pw) diet and the potential interactive effects of maternal and offspring postweaning diet on transcriptional response. Lastly, we explored sex as a biologic factor. Based on our prior work and others29, we hypothesized that pathways related to skeletal muscle metabolism, growth and insulin signaling would be differentially expressed in offspring exposed to maternal or postweaning WD, when compared to those maintained on a CD. Additionally, we anticipated male offspring to have less favorable transcriptional adaptations to a maternal WD than female offspring given reports of a worse metabolic phenotypes in adult male offspring30.

Results

mWD and pwWD increase fasting insulin but not adiposity in offspring

In male or female offspring, there was no difference in body weight by mWD or pwWD but the percentage of body fat was slightly lower in offspring on the pwWD (Table 1). Despite this lean phenotype, there was an interactive effect of maternal and postweaning diet on fasting insulin with elevated fasting insulin found in CD/WD offspring as compared to CD/CD and WD/WD offspring as has been previously shown in larger cohorts of offspring16. In sex specific comparisons, the interaction between mWD and pwWD for fasting insulin was only seen in female offspring, whereas in male offspring there was a main effect of pwWD to increase fasting insulin consistent with prior reports in a larger cohort16, however limited sample sizes may be impacting our ability to adequately detect effects of sex. Higher fasting insulin in CD/WD offspring was not specific to cohort year, maternal age, adiposity or offspring sex but this group was smaller in size than all other groups impacting power (Supplemental Tables S2). Fasting glucose was not different across groups. Elevated fasting insulin without changes in glucose is a hallmark sign of insulin resistance, although is usually accompanied by increased central adiposity31. In ivGTTs, insulin area under the curve (AUC) was elevated with pwWD in combined male and female comparisons and in males alone; however, in female offspring, insulin AUC was increased only in CD/WD offspring, similar to fasting insulin (Table 1). Glucose AUC was slightly lower in offspring exposed CD/WD compared to CD/CD. There were no significant difference in any measures between offspring of lean mWD dams (group 3) and offspring of obese mWD dams (group 5) when fed a pwCD. Despite these minimal changes in body composition, we have previously shown in this model early signs of metabolic dysregulation in liver, immune cells, islets and skeletal muscle of juvenile offspring exposed to mWD13,16,17,21,32,33.

Maternal phenotypes for the subset of animals used for in this study are described in Supplemental Tables S1 and S2 with a the larger cohort previously described34. Overall, adult females in the WD group with increased body fat (obese mWD) were also older, fed the mWD for longer and were more insulin resistant than lean mWD (Supplemental Tables S2). The obese mWD were not different in age as compared to lean mCD females.

Offspring gene expression is significantly different based on experimental group

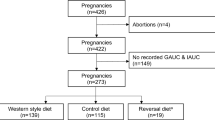

To test the long-term effects of maternal diet composition and maternal obesity on skeletal muscle transcriptional profiles and the individual and interacting effects of a postweaning diet composition, we selected offspring gastrocnemius samples from offspring of lean dams fed a mCD and who were then fed a pwCD (Group 1; CD/CD) or a pwWD (Group 2; CD/WD), offspring from lean dams fed a mWD and who were then fed a pwCD (Group 3; WD/CD) or a pwWD (Group 4; WD/WD), and offspring from obese dams fed mWD who were then fed a pwCD (Group 5; obWD/CD) (Fig. 1A–C). There were no samples available from offspring of obese dams weaned to pwWD limiting comparison of maternal obesity to pwCD animals. All experimental groups consisted of both male and female offspring. Sample size and sex distribution for each group is shown in Fig. 1B. We implemented a PCA combining all 40 samples across the five experimental groups (Supplemental Figure S1) to identify differences by group on skeletal muscle transcriptional profiles. We identified a clear outlier within WD/CD (Group 5) that is well outside the range of PC2 spread from the other data points. We did not identify any biological reasons in the health records or blood CBC or chemistry panels of the individual to explain this outlier nor did we identify any difference in coverage for the outlier (Supplemental Figure S2), but given its distinct clustering separate from all other datapoints, we chose to remove it from analyes. However, removing this outlier resulted in retainment of only a single male in Group 5 and therefore sex could not be considered when assessing impacts of maternal obesity on offspring gene expression. Removal of this outlier only impacted comparisons including individuals from obese dams. We then assessed relatedness of transcriptional profiles of the remaining 39 samples in PC space. After removal of the outlier, we observed a significant correlation between experimental group assignment and PC1 (P < 0.00001) with PC1 accounting for 27% of the variance observed (Fig. 1D). As groups are parsed by three main variables, postweaning diet, maternal diet, and maternal obesity, significant association of PC1 with experimental group warranted further exploration into the causal variable(s) for this partition of experimental groups.

Experimental Design and Hypotheses Tested. Schematic representation of experimental group composition, group metadata, hypotheses tested, and visualization of total variance in transcriptional profiles. Color-coding of groups is consistent throughout the manuscript. Yellow shading of the macaque indicates western-style diet (WD), black indicates a control diet (CD). (A) Composition of the five experimental groups in this study. Group 1 (purple): offspring weaned to a CD from lean dams fed a maternal (m)CD. Group 2 (pink): offspring fed a WD from lean dams fed a mCD. Group 3 (light blue): offspring fed a CD with lean dams fed a mWD. Group 4 (green): offspring fed a WD with lean dams fed a mWD. Group 5 (dark blue): offspring fed a CD with obese dams fed a WD. (B) Stacked bar chart representing total sample size in each group and sex composition of each group. Hatched lines indicate number of males, solid fill indicates females. (C) Groups used for each hypothesis test. (D) PCA of all 39 offspring included in the study.

Increased maternal adiposity does not impact muscle gene expression between mWD groups

To test for impacts of maternal obesity on offspring gene expression, we compared individuals from mWD and pwCD groups with dams that were obese vs lean (Group 3 vs Group 5). Given the removal of an outlier from Group 5, we only retained a single male offspring from an obese dam and therefore could only test for effects of maternal obesity with sexes combined (Fig. 2A). We performed hierarchical clustering of the top 1000 differentially expressed genes, which did not reveal any clustering by group (Fig. 2B). The lack of clustering was also observed using PCA; where there was no significant correlation of group with any PC (P > 0.05) (Fig. 2C). We then fit the data to a linear model accounting for maternal obesity and identified only a single significantly upregulated gene, transcriptional repressor GATA binding 1 (trsp1) (Supplemental Table S3; Fig. 2D). In muscle, trsp1 has been found to bind to the myog promoter to inhibit myogenin expression and myogenic differentiation35. Broadly, the global transcriptional patterns suggest no significant difference in offspring muscle gene expression with increased maternal adiposity when all dams consume a mWD.

Impact of maternal obesity on offspring gene expression. Colors indicate experimental group with triangles representing males and circles representing females. (A) Group composition and the number of genes retained post-filtering—includes all genes, not just significant differentially expressed genes. (B) Hierarchical clustering of the top 1,000 differentially expressed genes. (C) PCA of filtered transcriptional profiles. (D) Linear models and number of significant differentially expressed genes by maternal obesity.

mWD has a significant impact on muscle gene expression in offspring on pwCD

To assess the impact of maternal diet on offspring skeletal muscle gene expression, we performed three comparisons. First, we compared pwCD groups exposed to either mWD or mCD diet (Group 1 vs. Group 3) (Supplemental Figure S3A). As we did not observe any impact of maternal obesity on offspring gene expression, we performed a second comparison combining WD/CD groups (lean and obese dams) to be compared to CD/CD (Group 1 vs Group 3 & 5) (Fig. 3A). Combining Groups 3 & 5 allowed us to increase our sample size and account for offspring sex. Furthermore, repeating our analyses comparing mCD and mWD with and without inclusion of offspring from obese dams in the mWD group increases confidence that removal of the outlier in our original PCA from Group 5 (maternal obesity) did not influence our findings. We performed hierarchical clustering of the top 1,000 DE genes—regardless of significance—to assess partitioning of individuals. We observed distinct grouping of individuals from CD/CD vs. Lean WD/CD (Supplemental Figure S3B). This pattern was consistent across comparisons including and excluding offspring of obese WD/CD dams (Fig. 3B). PCA of each comparison confirmed these findings such that PC1 significantly correlated with group assignments in the Group 1 vs. Group 3 comparison and Group 1 vs Groups 3 & 5 combined comparison (P = 0.0001; P < 0.00001 respectively) with PC1 accounting for 32% of the observed variance (Supplemental Figure S3C; Fig. 3C). When combining Groups 3 and 5, we observed a significant correlation of read count by group (P = 0.042). When fitting our data to a linear model accounting for maternal diet, we identified 272 significantly upregulated and 620 significantly downregulated genes in pwCD groups comparing mWD to mCD diet (i.e. Group 1 vs. Group 3) (Supplemental Figure S3D; Supplemental Table S4). The number of genes increased with inclusion of offspring from obese dams to 338 significantly upregulated and 682 significantly downregulated genes (Fig. 3D; Supplemental Table S5).

Impact of maternal diet on offspring gene expression with obese and lean dams combined. Colors indicate experimental group with triangles representing males and circles representing females. Panels A-E represent the Group 1 vs Group 3 &5 comparison. Panels F-I represent the Group 2 vs Group 4 comparison. (A and F) Group composition and the number of genes retained post-filtering—includes all genes not just significant differentially expressed genes. (B and G) Hierarchical clustering of the top 1,000 differentially expressed genes. (C and H) PCA of filtered transcriptional profiles. (D and I) Linear models and number of significant differentially expressed genes by comparison. (E) Heat map of significant differentially expressed genes based on maternal diet and Venn diagram showing overlap between significantly up- or downregulated genes across the sexes. Consistent with the heat maps, red indicates upregulation and blue indicates down regulation.

We also investigated impacts of maternal diet by sex with our increase in sample size by inclusion of Group 5. We fit the data to a linear model accounting for maternal diet, sex, and an interaction effect between maternal diet and sex. We did not identify strong signals of differential expression between sexes (Fig. 3D) and instead only identified a small number of genes differentially expressed based on sex alone. Interestingly, we identified strong patterns of differential expression in both male and female offspring in CD/CD vs. WD/CD (Group 1 vs Group 3 & 5). In female offspring on pwCD, we identified 510 significantly upregulated and 808 significantly downregulated genes when comparing mWD vs. mCD (Fig. 3D) In males, we identified 185 significantly upregulated and 459 significantly downregulated genes when comparing between maternal diets (Fig. 3D; Supplemental Table S6). We did not detect an interaction effect likely due to limited sample sizes.

We next tested if males and females exhibited the same changes in expression by maternal diet by visulaizing overlapping sets of DE genes between the sexes (Group 1 vs Group 3&5) using a heat map for each sexes (Fig. 3E). We did not identify any genes significantly upregulated in one sex that were significantly downregulated in the other, but instead detected significant differential expression in many genes found only in one sex (data not shown). In upregulated genes, 26% of DE genes in females and 73% of DE genes in males were shared between the sexes. Similarly, 47% and 82% of DE genes in female and male offspring, respectively, were commonly downregulated.

We then compared pwWD offspring groups exposed to mCD or mWD (Group 2 vs. Group 4) (Fig. 3F). Unlike data from pwCD offspring, we did not, observe distinct grouping by maternal diet (i.e., Group 2 vs. Group 4) (Fig. 3G). Additionally, there was no correlation with any PC (P > 0.05) for Group 2 vs. Group 4 (Fig. 3H). When fitting these data to a linear model accounting for maternal diet, we identified only 1 significantly upregulated gene, filip1 and 2 significantly downregulated genes, mx1 and tmed3, in the pwWD groups (Group 2 vs. Group 4) (Fig. 3I; Supplemental Table S7).

pwWD significantly impacts muscle gene expression only in offspring from mCD groups

To assess the impact of postweaning diet on skeletal muscle gene expression, we first compared offspring fed a pwWD to those on a pwCD within the mCD groups (Group 1 vs. Group 2) (Fig. 4A). We again performed hierarchical clustering of the top 1,000 DE genes—regardless of significance—in each group pair to assess partitioning of individuals. We observed clear separation in clustering of individuals from Group 1 vs. Group 2, indicating a potential impact of postweaning diet on individuals from mCD dams (Fig. 4B). PCA mirrored these findings with PC1 significantly correlated with postweaning diet in Group 1 vs. Group 2 comparison (P = 0.012) accounting for 33% of the observed variance (Fig. 4C). These findings were further supported by fitting our data to a linear model accounting for postweaning diet. Comparison between postweaning diets in mCD offspring identified 287 significantly upregulated and 497 significantly downregulated genes (Fig. 4D; Supplemental Table S8). Unfortunately, limited sample sizes prevented testing for of differential expression by sex as we only had two females in the CD/WD group. However, we observed that CD/WD animals with the highest fasting insulin levels (Supplemental Table S1) exhibited the most extreme differential expression (Fig. 4E).

Impact of post-weaning diet on offspring gene expression. Colors indicate experimental group with triangles representing males and circles representing females. Panels A-E represent the comparison of Group 1 vs Group 2. Panels F-I represent the comparison of Group 3 vs Group 4. (A and F) Group composition and the number of genes retained post-filtering – includes all genes not just significant differentially expressed genes. (B and G) Hierarchical clustering of the top 1,000 differentially expressed genes. (C and H) PCA of filtered transcriptional profiles. (D and I) Linear models and number of significant differentially expressed genes by comparison. (E) Heat map of significant differentially expressed genes based on postweaning diet from dams fed a control diet. Asterisks indicate individuals with elevated fasting insulin.

We next compared the effect of postweaning diet (pwWD vs. pwCD) on muscle gene expression in offspring from mWD groups (Group 3 vs. Group 4) (Fig. 4F). Unlike offspring from mCD, we did not observe distinct clustering between Group 3 vs. Group 4 and no PC significant correlated with mWD groups (P > 0.05) (Fig. 4G–H). No DE genes were identified (Fig. 4I; Supplemental Table S9) suggesting pwWD had little or no effect on offspring gene expression profiles when offspring were exposed to mWD.

Female offspring exhibit interaction effects between maternal and post-weaning diets

To test for interaction effects between maternal and postweaning diets, we combined all data from offspring born to lean dams (Groups 1–4) (Fig. 5A). Using PCA, we identified distinct clustering by Group with PC1 significantly correlated with experimental group (P = 0.00007) accounting for 28% of the variance (Fig. 5B). When we fit these data to a linear model accounting for M diet, PW diet, and interaction between PW and M diets, we identified 121 significantly upregulated and 213 significantly downregulated genes due to the interaction between diets (Fig. 5C; Supplemental Table S10). When visualized as a heat map, there were clear cases of individuals not fitting the pattern of DE between Group 1 (CD/CD) and the other three groups (CD/WD; WD/CD; WD/WD) (Fig. 5D). Our previous findings of increased variance in males by maternal diet, a correlation of read count with group in the interaction comparison, and the presence of outliers in our DE gene heatmap led us to assess impacts of diet interactions by sex.

Interaction effects between maternal and post-weaning diets on offspring gene expression. Colors indicate experimental group with triangles representing males and circles representing females. (A) Group composition and the number of genes retained post-filtering—includes all genes not just significant differentially expressed genes. (B) PCA of filtered transcriptional profiles with sexes combined. (C) Linear model and number of significant differentially expressed genes. (D) Heat map of significant differentially expressed genes with sexes combined. (E) PCA of male filtered transcriptional profiles. (F) PCA of female filtered transcriptional profiles. (G) Linear model and number of significant differentially expressed genes in males and females separately. (H) Heat map of significant differentially expressed genes in female offspring. Brackets indicate groupings of observed patterns of differential expression (CD/CD vs CD/WD or WD/CD or WD/WD) and (CD/CD vs CD/WD or WD/CD vs WD/WD).

When separating groups by sex, we identified striking patterns of dissimilarity. In males, no clustering of groups or significant correlations with any PC were observed (P > 0.05) (Fig. 5E). In contrast, females exhibited clear clustering by group and a significant correlation of Group with PC1 (P = 0.00018) (Fig. 5F). We then fit a linear model accounting for M diet, PW diet, and an interaction effect between M and PW diets (Fig. 4G; Supplemental Tables S11 and S12). While we did not identify many significant DE genes (35 significantly upregulated and 18 significantly downregulated) in females, we did observe a clear clustering pattern in the heatmap of DE genes (Fig. 5H). In the heatmap, gene clusters presented in three groups (CD/CD vs CD/WD or WD/CD vs WD/WD) instead of the four treatment groups present in the experimental design (Fig. 5D). In female offspring, there were two different patterns of differential expression. In the 18 significantly downregulated genes, patterns were consistent with those observed with sexes combined; exposure to either a mWD or pwWD resulted in downregulation compared to the CD/CD group. In the 35 significantly upregulated genes, however, individuals exposed to either in mWD or pwWD diet—but not both—exhibited the strongest upregulation. Individuals from the WD/WD group exhibited patterns of expression that were more similar to the CD/CD group (Fig. 5H).

Analysis of top genes and pathway enrichment by mWD and offspring sex

Differential expression analyses based on maternal diet in offspring fed pwCD yielded the strongest signal (Group 1 vs Groups 3 & 5). To biologically assess the impacted genes/gene groups, we identified the most DE genes in all animals and in each sex (Table 2). Top differential genes were associated with four unique cell processes including transcription/RNA processing (ifi27, pan2, clasprp, otud1, leng8), mapk signaling (map3k6, map3k8), DNA damage and stress signaling (gadd45, neil1, hsf4) and metabolite flux (pla2G4B, slc25a1, slc7a6, scarf1). While individual gene dysregulation can have major biological consequences, we also performed KEGG pathway enrichment to identify biological pathways enriched for DE on sexes separate and sexes combined (Fig. 6). Top KEGG pathways included those pathways predicted to be different based on our prior work like insulin signaling, PI3K-AKT signaling, metabolic pathways and fatty acid degradation. Of the top enriched pathways, female offspring had a stronger influence than male offspring.

Heatmap of KEGG Pathway enrichment based on maternal diet. Heat map represents KEGG pathways enrichment for significant differentially expressed genes. GSEA methods used for identification of upregulated and downregulated pathways. KEGG pathways are represented alphabetically. Heat map columns represent sexes combined, females only, and males only. Intensity correlates with significance level.

Discussion

Fetal nutrient and growth factor availability during pregnancy significantly impacts muscle size, fiber composition, and programs responsiveness of pathways important for muscle growth, repair, and metabolism36,37 in mammals and avian species. Our previous findings in this model found impaired skeletal muscle mitochondrial function and reduced insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in fetal and juvenile offspring from dams consuming a mWD19,20,21. Here, we identify a persistent shift in transcriptional response to mWD that may underlie these programmed changes in offspring skeletal muscle function and subsequently increase the risk for developing insulin resistance and other metabolic diseases. Although a few studies have previously reported on global transcriptional analysis in offspring skeletal muscles from obese dams fed a high fat diet in rodent models29,38,39,40,41 our work is unique in several ways. Here, we are the first to compare skeletal muscle differential gene expression patterns: (1) in mWD offspring from lean and obese dams, (2) by maternal diet in offspring fed a pwWD and (3) associated with the interaction of maternal and postweaning diets by sex, in juvenile offspring prior to differences in offspring adiposity.

Our differential expression analyses revealed several interesting and somewhat unexpected findings. First, mWD was a major driver of DE and was not significantly different from maternal obesity. Given multigenerational studies of maternal obesity in rodent models42, we anticipated finding transcriptional changes but hypothesized that maternal obesity and insulin resistance, more so than mWD, would significantly impact offspring transcriptome in skeletal muscle. Evidence from several epidemiological studies and clinical cohorts strongly supports that maternal obesity, potentially mediated through poor metabolic health status24,43,44, increases infant adiposity and risk of offspring obesity1,45,46. Additionally, in a cohort of greater than 30,000 adult offspring, maternal obesity was linked to higher all-cause mortality and greater risk of cardiovascular disease in adult offspring47. Therefore, the lasting effects of mWD in the absence of maternal obesity or maternal insulin resistance48 on the skeletal muscle gene expression, when offspring were switched to a healthy control diet, was unexpected. More so, the lack of a further effect of maternal obesity as compared to mWD alone on offspring gene expression suggests a higher fat diet combined with highly digestible sugars is sufficient for metabolic reprogramming in offspring skeletal muscle.

Interestingly, while we observed robust differences in DE by maternal diet, with and without maternal obesity, when offspring were on pwCD, we identified very few DE genes and no significant PC correlation by maternal diet when offspring were on pwWD (Fig. 3F–I). In rodent models, a postweaning high fat and/or high sugar diet typically accelerates adiposity and insulin resistance in adult offspring from dams fed a WD compared to those from control dams49,50. Thus, one would anticipate finding stark differences in DE between these offspring groups when fed the pwWD. The lack of a difference in gene expression by maternal diet when offspring were fed a pwWD suggests that changes in gene expression due to a pwWD have a larger effect on transcription than maternal diet. It is also possible that the poor metabolic phenotype50 observed in adult offspring of obese dams can be attributed to differences in steps beyond gene transcription such as in RNA processing and translation, as suggested by our data in pwCD offspring, or through differential regulation by non-coding RNAs, like µRNAs51,52,53,54, not captured in this analysis. Few studies have compared changes in global gene expression patterns in offspring tissues due to differences in maternal adiposity or mWD when offspring are fed pwWD16,55,56 and none that we could find in skeletal muscle, specifically. In our primate model, gene expression analysis in offspring liver and islets showed robust differences with maternal diet even when offspring were fed a pwWD16,17 reflecting tissue-specific differences in gene responsiveness to the pwWD and/or in fetal metabolic adaptations to maternal diet that persist in postnatal period.

Skeletal muscle is highly adaptable to fuel availability, thus an early life exposure to elevated lipids, as with maternal obesity or WD, may lead to early shifts in fuel usage in fetal muscle. In fetal muscle from obese dams, oxidative metabolism in the absence of lipid substrates is reduced suggesting a metabolic reorganization to preferentially use lipids as opposed to glucose substrates20. In metabolically healthy individuals, switching to a higher fat diet leads to adaptations in skeletal muscle to promote fatty acids uptake, storage and oxidation in skeletal muscle57,58, in part, through transcriptional coordination of PPARs, PGC-1α and ERα signaling59,60,61. In contrast, those with metabolic disorders, such as obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes, demonstrate reduced mitochondrial content and diminished metabolic flexibility62,63 potentially driven by a blunted transcriptional response63. In our study, we observed differences in gene expression with pwWD vs. pwCD in skeletal muscle from offspring of mCD dams but found very little to no transcriptional changes by postweaning diet in offspring of mWD dams (Fig. 4G–I). The lack of a robust response in lean, healthy juvenile offspring from mWD dams suggest that mWD suppressed a transcriptional response to pwWD. When assessing interaction effects directly, we see clear clustering of individuals based on treatment group (Fig. 5B–D). Additionally, in our dataset the interactive effect was most pronounced in female offspring. Female offspring in the WD/WD group had a distinct pattern of gene response that was different from either the mWD or pwWD group alone. Together, these data suggest mWD may create a transcriptional pattern that “primes” muscle to be compatible with continued WD exposure and that may accelerate disease risk however an increase in sample sizes would elevate our ability to discern sex-specific effects. In contrast, a mismatch between maternal and postweaning diet leads to unique transcriptional pattern from that observed with the matched maternal and postweaning diet. Further investigation of these distinct gene sets may reveal mechanisms or biomarkers for individuals with increased risk.

Transcriptomic studies in liver, skeletal muscle and adipose tissue of fetal or adult offspring in mouse models identify differing transcriptional responses of male and female offspring to maternal obesity29, offering a probable explanation for sexually dimorphic metabolic outcomes as male offspring have been reported to have worse metabolic adaptations than their female counterparts29,55,64,65,66; however, some studies show worse outcomes in female offspring67,68. While these studies in rodents suggest fetal exposure to maternal obesity alters offspring metabolism through transcriptional mechanisms, factors such as degree of high fat diet exposure, housing temperature, developmental stage/maturity at birth, and litter births may limit the relevance to human populations. In our study, we also observed that male and female offspring were impacted differently by maternal diet when fed a pwCD, with females exhibiting more DE genes than males. However, very few genes were differentially expressed based on sex alone. Transcriptional responses in female offspring suggests fetal adaptations to mWD allows for genetic and molecular compensations that may support greater resiliency to later life environmental stressors compared to male offspring. In male offspring, we observed increased variance that was most clearly demonstrated when assessing interaction effects between maternal and postweaning diets. This increase in variance in males may account for why we see more significance in females alone. Given our observation that male and female offspring are affected differently by maternal diet, it is surprising that we have not observed sex differences in functional outcomes measures including insulin-stimulated glucose uptake19, or mitochondrial oxidative metabolism20,21 or their supporting cellular signaling pathways in offspring skeletal muscle. We propose that dysregulation of different pathways and/or in response across organ systems may lead to the same health outcome. Thus, it is important for future work to account for sex when assessing mechanisms for how maternal health or diet influences offspring outcomes.

While we were most interested in general patterns observed in this study—namely the impact of treatments (i.e. maternal obesity, maternal diet, and postweaning diet) on transcription globally, there are a few interesting genes and gene pathways identified that warrant further investigation in future studies. As maternal diet exhibited the most major effect on offspring gene expression, we investigated the top differentially expressed, and KEGG enriched pathways significantly impacted by this treatment in both sexes independently and combined (Table 2; Fig. 6). Within the group of top 15 DE genes, were several involved in stress-responsive mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) signaling pathway, map3k6, map3k8, and pla2g4b. In skeletal muscle, activation of MAPK, most notably p38 MAPK, and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK)69 but also MEKK8 (i.e. map3k8)70 is linked to insulin resistance. As noted, we and others71 have observed impaired glucose uptake in offspring skeletal muscle, which in our study was not linked to changes in insulin signaling typically associated with muscle insulin resistance observed in adult obesity. Changes in MAPK may be a mechanism to explain the insulin resistant phenotype in offspring muscle. Downregulation of ifi27 (IFN-α inducible protein 27) and gadd45g (growth arrest and DNA damage inducible gamma) was also consistent across sexes with mWD, with ifi27 exhibiting the most extreme downregulation in both sexes. In adipocytes, IFI27 localizes to inner mitochondria matrix, and promotes fatty acid oxidation through interactions with the trifunctional protein (HADHA)72,73. This is especially interesting as we have observed impaired fat oxidation in skeletal muscle from mWD offspring21.The downregulation of gadd45g was particularly surprising as it is typically upregulated due to stress74, and in fetal muscle, we observed gadd45g was upregulated in response to maternal obesity20. The opposite augmentation in expression due to mWD in the postweaning period may be an adaptation that leaves muscle cells more vulnerable to oxidative damage and may promote a proinflammatory phenotype as we have reported in hematopoietic stem and immune progenitor cells in these offspring13.

At the pathway level, DE genes were enriched in KEGG pathways for “Ribosome” in both sexes independently and combined resulting in significant upregulation. We also noted enrichment in downregulation of “Valine, leucine, isoleucine degradation”. This is not surprising as skeletal muscle is, in essence, the primary storage site for amino acids. Dysregulated amino acid metabolites were also noted in adolescent offspring in a baboon model of maternal obesity22. This also aligns with dysregulation of mTOR signaling which is commonly observed in aged- or insulin resistant muscles75,76 and was dysregulated in the pathway annotated “PI3K-Akt signaling”— enriched in females only and sexes combined. Upregulation of “Ribosomes” (enriched in all comparisons) combined with downregulation of “Valine, leucine, isoleucine degradation” and with downregulation of “Spliceosomes”— also observed in females only and sexes combined —suggests a potential breakdown of transcription-translation feedback loops, which could be impacting expression of other gene pathways. We also noted upregulation of several pathways involved in glucose uptake including “PI3K-Akt signaling”, “insulin resistance”, and “insulin signaling” with mWD. “CGMP-PKG signaling pathway” was also upregulated — enriched in females and sexes combined— and may contribute to differences in basal or contraction-stimulated glucose uptake through nitric oxide signaling77,78. Enrichment of many of these same pathways has been observed in skeletal muscle from male or female adult offspring in a mouse model of maternal obesity29. In our model, the upregulation of these pathways may be compensatory to the reduced insulin responsiveness measured in fetal and 1 yr-old juvenile skeletal muscle of mWD offspring19 and/or may be elevated due to the potential breakdown in transcription-translation feedback loops. Alternatively, there may be an upregulation in genes within these pathways that negatively regulate insulin action. Overall, these data indicate a persistent impact of maternal diet on offspring skeletal muscle transcriptome linked to regulation of glucose metabolism.

In summary, our results show that a maternal Western-style diet, even in the absence of maternal obesity and insulin resistance, is sufficient to reprogram offspring skeletal muscle transcriptional response in male and female offspring in a Japanese macaque model. The effects on gene expression were robust lasting years after exposure and influenced offspring responsiveness to a postweaning western-style diet in male and female offspring. We propose that this persistence in transcriptional response based on maternal diet contributes to the observed increased susceptibility to metabolic diseases in offspring. Future work will be aimed at identifying the cellular mechanisms leading to persistent changes in gene networks.

Limitations of the study

There are a few caveats to our findings. First, given our small sample size lack of difference in some comparisons may be due to a Type II error. Further exploration with an expanded sample sizes is needed to thoroughly address key points related to the potential impact of maternal adiposity compared mWD on offspring health. We do not explore mechanism for persistent gene changes. Many studies point to epigenetic changes in DNA methylation or histone acetylation79,80 including in our model13,81,82; It is likely that changes in chromating accessibility or transcription regulatory factors, like non-coding RNAs, underly the shifts in gene expression associated with maternal diet in offspring skeletal muscle. To understand the differences in males and females, we relied on general global patterns of expression differing between the sexes, and differences in significance across PC space to ascertain different responses by sex. Lastly, sex distribution was not matched in this analysis. Given other analyses showed difference in response between males and females, the unbalanced sex distribution between the two groups may obscure the findings.

Methods

Animals

All animal procedures were approved by and conducted in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Oregon National Primate Research Center (ONPRC) and Oregon Health and Science University. The ONPRC abides by the Animal Welfare Act and Regulations enforced by the USDA and the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the NIH. Experiments were designed and reported in accordance with the Animals in Research: Reporting In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines.

Experimental model

Adult female Japanese macaques were group housed in indoor/outdoor pens with 1–2 males and were fed ad libitum either a CD (15% calories from fat originating primarily from soybeans and corn; Monkey Diet no. 5000; Purina Mills) or WD (37% calories from fat primarily from corn oil, egg, and animal fat; TAD Primate Diet no. 5LOP, Test Diet, Purina Mills) for at least 1.5 years prior to pregnancy. Carbohydrate content differed between the two diets, with sugars (mainly sucrose and fructose) constituting 19% of the western-style diet but only 3% control diet. Monkeys on the WD were also given calorically dense treats (35.7% of calories from fat, 56.2% of calories from carbohydrates, and 8.1% of calories from protein) once daily. A subset of dams in the WD remained lean and insulin-sensitive like females fed a CD, while the majority of others became obese34,83—allowing us a unique opportunity to compare maternal western style diet with and without maternal obesity; an aspect not found in genetically similar rodent studies or human populations. (Supplemental Table S2). Adult females were classified as lean (≤ 27% body fat) or obese (≥ 30% body fat) based on percentage body fat obtained by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) in the fall preceding the pregnancy of interest20. Adult females in the WD group with increased body fat (obWD) were older, had been fed the WD for longer and were more insulin resistant (Supplemental Table S1). Insulin sensitivity was measured by an intravenous glucose tolerance test (ivGTT) prior to pregnancy determination and during the 3rd trimester as previously described34. Only singleton births were included in the cohort.

Offspring were born naturally and remained in their home colony until weaning. At 7–8 months of age, juvenile offspring were weaned to new group housing with 6–10 similarly aged juveniles from both maternal diet groups and 1–2 adult females and assigned to either the pwCD or pwWD. All experimental groups consisted of both male and female offspring. In total, we included 40 offspring from 9 lean mCD dams, 13 lean and 7 obese mWD dams (Supplemental Table S1). Offspring body weight, body composition by DEXA and ivGTT were measured within 2 months of necropsy (~ 36 months of age) as previously described16.

Skeletal muscle collection

Animals were sacrificed between 37 and 40 months of age with an average age of 38 months for all groups. Prior to necropsy, animals were sedated with 15–20 mg/kg ketamine and transported to necropsy under sedation. An intravenous dose of sodium pentobarbital at 25 mg/kg is given to induce deep sedation and then followed by exsanguination following the American Veterinary Medical Association guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals. Skeletal muscles including gastrocnemius, soleus, vastus lateralis, and rectus femoris were rapidly dissected of fascia and portions were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Frozen muscle was stored at − 80 °C until analysis.

RNA extraction

RNA was extracted from approximately 50 mg of pulverized gastrocnemius using PureLink RNA mini kit (Thermofisher, Waltham, MA, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions except homogenization in trizol was performed using an Omni bead mill with a CryoCool system. Each cryomill tube had 5 × 2.8 mm ceramic beads (Omni Inc, Kennesaw, GA, USA) and was run for 2 × 30 secs at 6 m/s with a 10 s dwell period.

RNA-seq data processing and normalization

RNA-seq library preps were generated using the Kapa stranded mRNA-seq kit (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Samples were individually barcoded and sequenced across four lanes on the Illumina Hi-Seq 4000 (Illumina Inc, San Diego, CA, USA) with all samples represented in each lane. Sequencing reads were demultiplexed via Illumina’s bcl2fastq software (Illumina Inc, San Diego, CS, USA) and trimmed and quality filtered using BBDuk (BBMap-Bushnell B.—sourceforge.net/projects/bbmap/). Reads were aligned to the rhesus macaque reference genome version 8.0.1 using the STAR aligner84 version 2.5.4b and read count tables generated using the—quantMode gene counts function in STAR. Preprocessing of read counts was performed with integrated Differential Expression and Pathway analysis (iDEP) version 0.9385. This package implements R programming language version 4.0586 and Bioconductor87,88 version 3.12. Total read counts per gene were input and metadata for each hypothesis tested separately into iDEP93. A cut-off of 0.5 CPM (copies per million) was used to filter genes with low counts for all libraries prior to differential expression analyses. We normalized and log2 transformed gene counts using EdgeR89 in IDEP9385. When assessing all 40 individuals for read count distributions, we identified a correlation between read count and maternal diet (P = 0.00657) (Supplemental Figure S2). This correlation did not persist in any of our hypothesis tests and no significant correlations between read count and other experimental variables were found when assessing impacts of PW-diet, M-diet, or M-obesity, (with sexes combined or split). There were also no correlations identified when testing for interaction effects between PW-diet and M-diet when groups were split by sex. However, we did see a significant correlation of read count and Group (P = 0.00729) and read count and M-diet (P = 0.0067) in testing for PW-diet and M-diet interaction effects with sexes combined.

An initial concern with our experimental design was that variables unrelated to experimental group, and their main variables, could be influencing transcriptional profiles, specifically, the cohort year in which offspring were reared and the genetic relatedness of individuals (Supplemental Table S2). For each cohort year (Supplemental Table S1), we observed a complete span of PC1 space, with no significant correlations between any PC and cohort year (Supplemental Figure S4). We therefore ignored cohort year as a covariate as there was no effect. Importantly, while there is some variability in relatedness of our combined 40 Japanese macaque offspring, all individuals are closely related. In all but one case, dams reared one or two offspring with one dam rearing three offspring (Supplemental Table S1). Offspring were randomized across treatment groups (i.e., one dam may have reared two offspring in the same treatment group or in different treatment groups). The identity of sires is unknown; however, the family structure of Japanese macaques limits the number of possible sires so in all cases there are one or two sires possible within each harem.

Differential expression analysis parameters and pathway enrichment

iDEP9385 was used for differential expression analyses. Multivariate patterns of gene expression between experimental groups were characterized with Principal Component Analysis (PCA). Coordinates were exported from iDEP93 and visualized in RStudio using Base R86. Heatmaps were generated using data visualization in IDEP93 implementing hierarchical clustering of the top 1,000 DE genes. Differential expression analyses were performed with DESeq290 with a minimum fold change of 1.5 and a False Discovery Rate (FDR) of 0.05. We selected main effects for each comparison with interaction effects included when appropriate. We performed KEGG Pathway enrichment usingGene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) with an FDR of 0.1. KEGG91 enrichment was performed using Ensembl Release 100.

Data availability

All sequencing reads are available on the Sequencing Read Archive (SRA) under Submission ID SUB15309712.

References

Heslehurst, N. et al. The association between maternal body mass index and child obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Med. 16, e1002817 (2019).

Barker, D. J. P. The origins of the developmental origins theory. J. Intern. Med. 261, 412–417 (2007).

Barker, D. J. P. et al. Fetal nutrition and cardiovascular disease in adult life. The Lancet 341, 938–941 (1993).

Bateson, P. et al. Developmental plasticity and human health. Nature 430, 419–421 (2004).

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Obesity Data and Statistics. (2021).

Pan, L., Sherry, B., Njai, R. & Blanck, H. M. Food insecurity is associated with obesity among US adults in 12 States. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 112, 1403–1409 (2012).

Coleman-Jensen, A., Rabbitt, M. P., Gregory, C. A. & Singh, A. Household Food Security in the United States in 2019. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/99282/err-275.pdf.

Ortiz-Marrón, H. et al. Household food insecurity and its association with overweight and obesity in children aged 2 to 14 years. BMC Public Health 22, 1930 (2022).

The RISE Consortium*. Effects of Treatment of impaired glucose tolerance or recently diagnosed type 2 diabetes with metformin alone or in combination with insulin glargine on β-cell function: Comparison of responses in youth and adults. Diabetes db (2019) https://doi.org/10.2337/db19-0299.

Arslanian, S. et al. Evaluation and management of youth-onset type 2 diabetes: A position statement by the American diabetes association. Diabetes Care 41, 2648–2668 (2018).

The RISE Consortium et al. Metabolic contrasts between youth and adults with impaired glucose tolerance or recently diagnosed type 2 diabetes: II. Observations using the oral glucose tolerance test. Diabetes Care 41, 1707–1716 (2018).

DeFronzo, R. A. & Tripathy, D. Skeletal muscle insulin resistance is the primary defect in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 32, S157–S163 (2009).

Nash, M. J. et al. Maternal diet alters long-term innate immune cell memory in fetal and juvenile hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in nonhuman primate offspring. Cell Rep. 42, 112393 (2023).

Prince, A. L. et al. The development and ecology of the Japanese macaque gut microbiome from weaning to early adolescence in association with diet. Am. J. Primatol. 81, e22980 (2019).

Elsakr, J. M. et al. Maternal Western-style diet affects offspring islet composition and function in a non-human primate model of maternal over-nutrition. Mol. Metab. 25, 73–82 (2019).

Nash, M. J. et al. Maternal Western diet is associated with distinct preclinical pediatric NAFLD phenotypes in juvenile nonhuman primate offspring. Hepatol. Commun. 7, e0014–e0014 (2023).

Carroll, D. T. et al. Maternal Western-style diet in nonhuman primates leads to offspring islet adaptations including altered gene expression and insulin hypersecretion. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 324, E577–E588 (2023).

Nash, M. J. et al. Maternal Western diet exposure increases periportal fibrosis beginning in utero in nonhuman primate offspring. JCI Insight 6, e154093 (2021).

Campodonico-Burnett, W. et al. Maternal obesity and western-style diet impair fetal and juvenile offspring skeletal muscle insulin-stimulated glucose transport in nonhuman primates. Diabetes 69, 1389–1400 (2020).

McCurdy, C. E. et al. Maternal obesity reduces oxidative capacity in fetal skeletal muscle of Japanese macaques. JCI Insight 1, 86612 (2016).

Greyslak, K. T. et al. A maternal Western-style diet impairs skeletal muscle lipid metabolism in adolescent Japanese macaques. Diabetes https://doi.org/10.2337/db23-0289 (2023).

Ampong, I. et al. Maternal obesity alters offspring liver and skeletal muscle metabolism in early post-puberty despite maintaining a normal post-weaning dietary lifestyle. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 36, e22644 (2022).

Bayol, S. A., Macharia, R., Farrington, S. J., Simbi, B. H. & Stickland, N. C. Evidence that a maternal “junk food” diet during pregnancy and lactation can reduce muscle force in offspring. Eur. J. Nutr. 48, 62–65 (2009).

Erickson, M. L. et al. Maternal metabolic health drives mesenchymal stem cell metabolism and infant fat mass at birth. JCI Insight 6, e146606 (2021).

Jevtovic, F. et al. Effects of maternal exercise on infant mesenchymal stem cell mitochondrial function, insulin action, and body composition in infancy. Physiol. Rep. 12, e16028 (2024).

Jevtovic, F. et al. Myogenically differentiated mesenchymal stem cell insulin sensitivity is associated with infant adiposity at 1 and 6 months of age. Obes. Silver Spring Md 31, 2349–2358 (2023).

Saben, J. L. et al. Maternal metabolic syndrome programs mitochondrial dysfunction via germline changes across three generations. Cell Rep. 16, 1–8 (2016).

Sales, V. M., Ferguson-Smith, A. C. & Patti, M.-E. Epigenetic mechanisms of transmission of metabolic disease across generations. Cell Metab. 25, 559–571 (2017).

Kelly, A. C. et al. Transcriptomic responses are sex-dependent in the skeletal muscle and liver in offspring of obese mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 323, E336–E353 (2022).

Sandovici, I., Fernandez-Twinn, D. S., Hufnagel, A., Constância, M. & Ozanne, S. E. Sex differences in the intergenerational inheritance of metabolic traits. Nat. Metab. 4, 507–523 (2022).

Kahn, S. E., Hull, R. L. & Utzschneider, K. M. Mechanisms linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature 444, 840–846 (2006).

Nash, M. J. et al. Maternal Western diet programmes bile acid dysregulation and hepatic fibrosis in fetal and juvenile macaques. Liver Int. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Liver 45, e16236 (2025).

Carroll, D. T. et al. Analysis of beta-cell maturity and mitochondrial morphology in juvenile non-human primates exposed to maternal Western-style diet during development. Front. Endocrinol. 15, 1417437 (2024).

Elsakr, J. M. et al. Western-style diet consumption impairs maternal insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism during pregnancy in a Japanese macaque model. Sci. Rep. 11, 12977 (2021).

Hüttner, S. S. et al. A dysfunctional miR-1-TRPS1-MYOG axis drives ERMS by suppressing terminal myogenic differentiation. Mol. Ther. 31, 2612–2632 (2023).

Yang, J. Enhanced Skeletal Muscle for Effective Glucose Homeostasis. in Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science vol. 121 133–163 (Elsevier, 2014).

Reed, S. A., Raja, J. S., Hoffman, M. L., Zinn, S. A. & Govoni, K. E. Poor maternal nutrition inhibits muscle development in ovine offspring. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 5, 43 (2014).

Kasch, J. et al. Insulin sensitivity linked skeletal muscle Nr4a1 DNA methylation is programmed by the maternal diet and modulated by voluntary exercise in mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 57, 86–92 (2018).

Latouche, C. et al. Maternal overnutrition programs changes in the expression of skeletal muscle genes that are associated with insulin resistance and defects of oxidative phosphorylation in adult male rat offspring. J. Nutr. 144, 237–244 (2014).

Salto, R. et al. Programming Skeletal muscle metabolic flexibility in offspring of male rats in response to maternal consumption of slow digesting carbohydrates during pregnancy. Nutrients 12, 528 (2020).

Zhao, L. et al. Obesity impairs embryonic myogenesis by enhancing BMP signaling within the dermomyotome. Adv. Sci. 8, 2102157 (2021).

Ferey, J. L. A. et al. A maternal high-fat, high-sucrose diet induces transgenerational cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction independently of maternal mitochondrial inheritance. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 316, H1202–H1210 (2019).

Chaves, A. B. et al. Infant mesenchymal stem cell insulin action is associated with maternal plasma free fatty acids, independent of obesity status: The healthy start study. Diabetes 71, 1649–1659 (2022).

Barbour, L. A. et al. Postprandial triglycerides predict newborn fat more strongly than glucose in women with obesity in early pregnancy. Obesity 26, 1347–1356 (2018).

Montazeri, P. et al. Maternal metabolic health parameters during pregnancy in relation to early childhood BMI trajectories. Obesity 26, 588–596 (2018).

Bowers, K. et al. Elevated anthropometric and metabolic indicators among young adult offspring of mothers with pregestational diabetes: Early results from the transgenerational effect on adult morbidity study (the TEAM study). J. Diabetes Res. 2021, 1–10 (2021).

Reynolds, R. M. et al. Maternal obesity during pregnancy and premature mortality from cardiovascular event in adult offspring: Follow-up of 1 323 275 person years. BMJ 347, f4539–f4539 (2013).

Fernandez-Twinn, D. S. et al. Exercise rescues obese mothers’ insulin sensitivity, placental hypoxia and male offspring insulin sensitivity. Sci. Rep. 7, 44650 (2017).

Nicholas, L. M. et al. The early origins of obesity and insulin resistance: Timing, programming and mechanisms. Int. J. Obes. 40, 229–238 (2016).

Li, M., Sloboda, D. M. & Vickers, M. H. Maternal obesity and developmental programming of metabolic disorders in offspring: Evidence from animal models. Exp. Diabetes Res. 2011, 1–9 (2011).

Houshmand-Oeregaard, A. et al. Increased expression of microRNA-15a and microRNA-15b in skeletal muscle from adult offspring of women with diabetes in pregnancy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 27, 1763–1771 (2018).

Kanakis, I. et al. Small-RNA sequencing reveals altered skeletal muscle microRNAs and snornas signatures in weanling male offspring from mouse dams fed a low protein diet during lactation. Cells 10, 1166 (2021).

Yan, X. et al. Maternal obesity downregulates microRNA let-7g expression, a possible mechanism for enhanced adipogenesis during ovine fetal skeletal muscle development. Int. J. Obes. 2005(37), 568–575 (2013).

Cracco, R. C., Alexandre, P. A., Polizel, G. H. G., Fernandes, A. C. & de Almeida Santana, M. H. Evaluation of muscle long non-coding RNA profile during rearing and finishing phase of bulls subjected to different prenatal nutritional strategies. Anim. Open Access J. MDPI 14, 652 (2024).

Savva, C. et al. Maternal high-fat diet programs white and brown adipose tissue lipidome and transcriptome in offspring in a sex- and tissue-dependent manner in mice. Int. J. Obes. 46, 831–842 (2022).

Cui, J. et al. Maternal metformin treatment during gestation and lactation improves skeletal muscle development in offspring of rat dams fed high-fat diet. Nutrients 13, 3417 (2021).

Nemeth, P. M., Rosser, B. W., Choksi, R. M., Norris, B. J. & Baker, K. M. Metabolic response to a high-fat diet in neonatal and adult rat muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 262, C282–C286 (1992).

Kelley, D. E., Mokan, M., Simoneau, J. A. & Mandarino, L. J. Interaction between glucose and free fatty acid metabolism in human skeletal muscle. J. Clin. Invest. 92, 91–98 (1993).

Lin, J., Handschin, C. & Spiegelman, B. M. Metabolic control through the PGC-1 family of transcription coactivators. Cell Metab. 1, 361–370 (2005).

Muoio, D. M. & Koves, T. R. Skeletal muscle adaptation to fatty acid depends on coordinated actions of the PPARs and PGC1 alpha: Implications for metabolic disease. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. Physiol. 32, 874–883 (2007).

Hevener, A. L., Ribas, V., Moore, T. M. & Zhou, Z. The impact of skeletal muscle ERα on mitochondrial function and metabolic health. Endocrinology 161, bqz017 (2020).

Boyle, K. E. et al. A high-fat diet elicits differential responses in genes coordinating oxidative metabolism in skeletal muscle of lean and obese individuals. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 96, 775–781 (2011).

Holloway, G. P., Bonen, A. & Spriet, L. L. Regulation of skeletal muscle mitochondrial fatty acid metabolism in lean and obese individuals. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 89, 455S-S462 (2009).

Lomas-Soria, C. et al. Maternal obesity has sex-dependent effects on insulin, glucose and lipid metabolism and the liver transcriptome in young adult rat offspring: Maternal obesity programs liver transcriptome changes in rat offspring. J. Physiol. 596, 4611–4628 (2018).

Aiken, C. E. & Ozanne, S. E. Sex differences in developmental programming models. Reproduction 145, R1–R13 (2013).

Liang, X. et al. Maternal obesity epigenetically alters visceral fat progenitor cell properties in male offspring mice. J. Physiol. 594, 4453–4466 (2016).

Khan, I. Y. et al. A high-fat diet during rat pregnancy or suckling induces cardiovascular dysfunction in adult offspring. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 288, R127–R133 (2005).

Bayol, S. A., Simbi, B. H., Bertrand, J. A. & Stickland, N. C. Offspring from mothers fed a ‘junk food’ diet in pregnancy and lactation exhibit exacerbated adiposity that is more pronounced in females: Maternal junk food diet and obesity in offspring. J. Physiol. 586, 3219–3230 (2008).

Lawan, A. et al. Skeletal muscle-specific deletion of MKP-1 reveals a p38 MAPK/JNK/Akt signaling node that regulates obesity-induced insulin resistance. Diabetes 67, 624–635 (2018).

Perfield, J. W. et al. Tumor progression locus 2 (TPL2) regulates obesity-associated inflammation and insulin resistance. Diabetes 60, 1168–1176 (2011).

Simar, D., Chen, H., Lambert, K., Mercier, J. & Morris, M. J. Interaction between maternal obesity and post-natal over-nutrition on skeletal muscle metabolism. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. NMCD 22, 269–276 (2012).

Jin, W., Jin, W. & Pan, D. IFI27 is indispensable for mitochondrial function and browning in adipocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 501, 273–279 (2018).

Cui, X. et al. IFI27 integrates succinate and fatty acid oxidation to promote adipocyte thermogenic adaption. Adv. Sci. 10, 2301855 (2023).

Takekawa, M. & Saito, H. A family of stress-inducible GADD45-like proteins mediate activation of the stress-responsive MTK1/MEKK4 MAPKKK. Cell 95, 521–530 (1998).

Barclay, R. D., Burd, N. A., Tyler, C., Tillin, N. A. & Mackenzie, R. W. The role of the IGF-1 signaling cascade in muscle protein synthesis and anabolic resistance in aging skeletal muscle. Front. Nutr. 6, 146 (2019).

Howell, J. J. & Manning, B. D. mTOR couples cellular nutrient sensing to organismal metabolic homeostasis. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 22, 94–102 (2011).

Etgen, G. J., Fryburg, D. A. & Gibbs, E. M. Nitric oxide stimulates skeletal muscle glucose transport through a calcium/contraction—and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase–independent pathway. Diabetes 46, 1915–1919 (1997).

McConell, G. K. & Kingwell, B. A. Does nitric oxide regulate skeletal muscle glucose uptake during exercise?: Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 34, 36–41 (2006).

Pérez, R. F. et al. Longitudinal genome-wide DNA methylation analysis uncovers persistent early-life DNA methylation changes. J. Transl. Med. 17, 15 (2019).

Li, Y. Epigenetic mechanisms link maternal diets and gut microbiome to obesity in the offspring. Front. Genet. 9, 342 (2018).

Aagaard-Tillery, K. M. et al. Developmental origins of disease and determinants of chromatin structure: Maternal diet modifies the primate fetal epigenome. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 41, 91–102 (2008).

Suter, M. A. et al. In utero exposure to a maternal high-fat diet alters the epigenetic histone code in a murine model. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 210(463), e1-463.e11 (2014).

Harris, R. A. et al. Genomic variants associated with resistance to high fat diet induced obesity in a primate model. Sci. Rep. 6, 36123 (2016).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013).

Ge, S. X., Son, E. W. & Yao, R. iDEP: An integrated web application for differential expression and pathway analysis of RNA-Seq data. BMC Bioinformatics 19, 534 (2018).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

Gentleman, R. C. et al. Bioconductor: Open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 5, R80 (2004).

Huber, W. et al. Orchestrating high-throughput genomic analysis with bioconductor. Nat. Methods 12, 115–121 (2015).

Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. EdgeR: A bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140 (2010).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Kanehisa, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M., Furumichi, M. & Tanabe, M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D457–D462 (2016).

Acknowledgements

All nonhuman primate studies were supported, in part, by the Oregon National Primate Research Center grant P51 OD011092 from the National Institutes of Health/Office of the Director. B.H., T.A.D., D.L.T., M.G., S.R.W., K.M.A., J.E.F., P.K., and C.E.M. were supported by NIH/NIDDK Grants R24 DK090964 and R01 DK128187. E.A.B. was supported by the University of Oregon Office of the Vice President for Research and Innovation Incubating Interdisciplinary Initiatives award to C.E.M and E.A.B. The authors thank the veterinarians and veterinarian staff of the Oregon National Primate Research Center for their excellent care of the animals in this study. The authors also acknowledge Clayton M. Small for insights on statistical analyses. C.E.M. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to the data included in this study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.E.M. conceptualized and designed the study in collaboration with the NHP consortium including S.R.W., K.M.A., J.E.F., P.K., and M.G. Tissue acquisition was performed at Oregon Health Sciences University led by P.K with T.A.D and D.L.T. Molecular work was performed by B.H. Bioinformatic analyses were performed by E.A.B. with L.N. and D.W.T. Statistical analysis and data visualization were performed by E.A.B. The manuscript was written by E.A.B and C.E.M. with all authors contributing to the editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Beck, E.A., Hetrick, B., Nassar, L. et al. Maternal Western-style diet has a persistent effect on offspring gene expression in skeletal muscle of Japanese macaques. Sci Rep 15, 21324 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00828-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00828-3