Abstract

Miniaturized accelerometers incorporated in pacing leads attached directly onto the heart provide a means for continuous monitoring of cardiac function. Several functional accelerometer indices first require detection of valve events. We previously developed a deep neural network to detect timing of aortic valve closure and opening. In this study we trained and tested the performance of the network to detect timing of mitral valve closure (MVC) and opening (MVO). Furthermore, we extracted four different functional indices based on the detected valve events and investigated how these indices reflected changes in cardiac function. The neural network was tested on approximately 5900 heartbeats from 289 recordings in a total of 46 animals with a cardiac accelerometer attached to the heart during various interventions that altered function. The neural network correctly detected MVO and MVC in 89.6% and 87.5% of the beats, respectively, with a mean absolute error of 13 ms between the detected values and the annotated targets for both. The functional indices correlated well with measured left ventricular stroke work (0.67 < r < 0.84) and showed expected changes for the different interventions. Hence, automatic detection of valve events is feasible and facilitates improved cardiac monitoring when using implanted cardiac accelerometers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Insertion of motion sensors directly into the myocardium has been a gold standard method to assess cardiac function for decades1,2. Previously, this highly invasive method has not been suitable for clinical use in humans and thus been restricted to animal studies. However, in the past decade, advances in accelerometer miniaturization have enabled the incorporation of such sensors into pacing leads attached to the heart wall, allowing the assessment of myocardial function in patients. This technique is now commercially available for clinical use in cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT)3,4. We have also proposed to incorporate accelerometers into temporary pacing leads that are attached to the epicardium during cardiac surgery5. This will allow continuous monitoring of cardiac function during the critical phase of the patient’s recovery in the intensive care unit. Conventional monitoring of these patients includes electrocardiogram (ECG), pulse index continuous cardiac output (PiCCO), and arterial blood pressure which all have limitations6. An accelerometer attached to the heart has the potential to improve monitoring in these patients as it would provide continuous measurements of myocardial motion, which may be more directly linked to function. The acceleration trace has a complex waveform, but when integrated once to velocity and twice to displacement (Fig. 1), the resulting traces resemble velocity and strain traces which are more familiar to most echocardiographers, making them easier to interpret. To assess cardiac function, functional indices must be extracted from the sensor signals. Many such indices are extracted from specified phases of the cardiac cycle, such as isovolumic contraction, ejection, isovolumic relaxation, or filling. This requires segmenting the signal into these phases by detecting valve events. Manual detection is challenging, time consuming and impractical for continuous or home monitoring, so robust and accurate automated methods are needed.

We previously proposed a method to detect mitral and aortic valve events from cardiac accelerometer signals using classical signal processing7. This method required first demarcating heart cycles by detecting ECG R-peaks, thus necessitating additional ECG measurements. The study was on a smaller dataset with a limited number of interventions where the accelerometer waveform maintained a relatively similar pattern, which may be a requirement for such methods to work properly. When applied to interventions such as pacing, which markedly changed the waveform pattern, the performance dropped8,9.

As an alternative to conventional signal processing, deep neural networks offer the advantage of being able to identify patterns and features at a deeper level of abstraction, beyond what is visible to humans. This can lead to more robust and generally applicable valve detection methods. In a subsequent study, we tested deep neural network-based detection for identifying aortic valve events. This method provided accurate and robust predictions on a more versatile dataset that included data from both pigs and canines, covering multiple interventions with varying cardiac motion and cardiac function8,9. The neural network-based detection method was able to handle a broad range of heart rates and did not require additional sensor inputs, such as ECG. However, the network’s ability to detect mitral valve events was not tested due to the large amount of annotated data needed to train such models, which would require automatic annotation. This was feasible for aortic valve opening and closing which were automatically extracted as maximum and minimum LV dP/dt, respectively, as LV pressure (LVP) was measured in all experiments. In contrast, detecting mitral valve events would additionally require left atrial (LA) pressure and LV volume measurements, as our previous definitions7 identified mitral valve opening as first diastolic crossover of LV and LA pressures and mitral valve closure as maximum volume. Such measurements were performed in too few experiments to generate a sufficient dataset large enough to train and test a neural network.

The ability of such a deep neural network to detect mitral valve closure and opening is therefore unknown. As the bicuspid mitral valve leaflets are larger than the tricuspid aortic valve leaflets, and because the active contractile tension, LV pressure, and blood flow differ at the time of the various valve events, the vibration pattern in the signal will also differ. The feasibility of detecting the different events may therefore vary and needs to be tested. In this study, we first found and validated a method for automatic annotation of mitral valve opening and closing events using only LVP. This then allowed us to investigate the performance of a deep neural network to detect mitral valve events. As a second aim, we tested extraction of four indices which depend on the detected mitral and aortic valve events from the deep neural network in order to demonstrate the ability for continuous and automated cardiac function monitoring. This included two novel functional indices, post systolic displacement and pressure displacement loop area efficiency, and estimation of the LV pressure trace based on the four valve events7,10, which we compared and validated against the invasively measured LV pressure trace.

An example of a cardiac acceleration signal is shown in the upper panel, which is then integrated to provide velocity and displacement, with ECG for reference. The acceleration signal has a complex waveform. During the phases with valve closure and opening, interactions between wall motion and valve events generate accelerations, decelerations, and heart sounds, which appear as vibrations in the signal11.

Methods

Animal preparation

The study utilized data collected from a series of experiments previously conducted by our research group. Ethical approval for the animal protocols were obtained from the Norwegian Food Safety Authority (FOTS ID: 8628, 9303 and 17644). All experiments were conducted in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines and in accordance with the relevant ethical standards and regulations. The experiments were terminal and performed under full anesthesia (either using morphine and pentobarbital or fentanyl and propofol) as previously described5,12.

The experiments followed different instrumentation protocols, however all of them had LVP and acceleration signals recorded simultaneously during different interventions. LVP was recorded using a calibrated micromanometer-tipped catheter (MPC-500, Millar Instruments Inc, Houston, TX). A tri-axial accelerometer sensor (MPU9250, InvenSense Inc, San Jose, CA, USA) was sutured to the epicardium in the LV apical anterior region. The accelerometer’s x-, y-, and z-axis were aligned with the longitudinal, circumferential, and radial directions, respectively (Fig. 2). Depending on the protocol, data were recorded at either 650–1000 Hz in canines and either 250–500 Hz in pigs. Lastly, in a few pigs a 16-mm ultrasonic peri-vascular flow probe (Medistim, Oslo, Norway) was placed around the ascending aorta to calculate cardiac output. Cardiac output and flow were then used to calculate LV stroke work (LVSW) as:

In the canine model, three pairs of sonomicrometric crystals (Sonometrics Corporation, London, Ontario, Canada) were implanted in the LV subendocardium to measure the LV long-axis diameter, septal-to-lateral wall short-axis diameter, and the anterior–posterior short-axis diameter. LV volume was then calculated using an elliptical formulation equal to the product of π/6 and the three diameters. Most recordings were performed under open chest conditions, however closed chest recordings were performed in nine pigs. In these nine pigs, two pairs of sonomicrometric crystals were implanted to measure LV volume as the product of π/6, the LV long-axis diameter, and the square of the anterior–posterior short-axis diameter. Changes in end diastolic volume (EDV) were used to verify changes in preload.

Experimental protocol

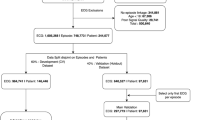

Data for this study were obtained from a total of 46 animals (19 canines and 27 pigs), through 289 recordings with a typical duration from 15 to 30 s, from baseline and 14 different interventions altering cardiac function. These interventions included:

-

Epinephrine infusion - increases heart rate, contractility, and overall cardiac output.

-

Esmolol infusion - decreases heart rate and contractility.

-

Myocardial ischemia - reduces blood flow, leading to impaired contractility at a local level.

-

Niprid infusion - causes vasodilation, reducing afterload.

-

Volume loading - increases preload, leading to enhanced cardiac output and stroke volume.

-

Volume unloading - decreases preload, reducing cardiac output and stroke volume.

-

Dobutamine infusion - increases contractility, stroke work and cardiac output.

-

Right ventricular pacing (RVP) - introduces electrical and mechanical dyssynchrony.

-

Induction of left bundle branch block (LBBB) - introduces electrical and mechanical dyssynchrony.

-

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) - pacing to mitigate dyssynchrony in LBBB.

Additionally, there were combinations of ischemia and dobutamine, LBBB and ischemia, LBBB and dobutamine, and volume loading during LBBB.

Not all interventions were performed in every animal due to variations in experimental protocols. Some animals also had multiple recordings for certain interventions, such as recordings obtained at different levels of volume loading during an experiment. LBBB and CRT were only performed in some canines, as induction of LBBB in pigs does not produce sufficient dyssynchrony. Tables 1 and 2 list the interventions in canines and pigs with the number of animals and recordings of each. Figure 3 shows some representative recordings from different interventions.

Determination of ground truth for valve events

The ground truths for aortic valve opening (AVO) and closing (AVC) were defined as the maximum and minimum points of the rate of change of LV pressure (dP/dtmax and dP/dtmin), respectively, as in our previous study8 (Fig. 4). To define mitral valve opening (MVO) and closing (MVC) events, we adopted an algorithm from the MICOR system13. Figure 4 shows this algorithm which uses a “geometric” approach on the LVP trace to identify end diastole (i.e. MVC). From previous analysis in our experiments, we have observed that the LV pressure at MVO and MVC are quite similar. Hence, we extended this algorithm so that MVO was defined as the timepoint at which LVP during diastole was identical to the pressure at MVC (Fig. 4).

The procedure to define MVC and MVO in Fig. 4 was validated in a subgroup of 5 animals where we had additional recordings of LV volume and left atrial pressure (LAP), which were used to find reference timepoints for these events7. The reference timing of MVC was defined as the point of maximum LV volume at end diastole and MVO as the first diastolic crossover point of LVP and LAP. Mean difference (± SD) for MVC was 2 ± 7 ms, and for MVO 1 ± 3 ms (Fig. 5). Given that a heart cycle typically exceeds 500 ms, an error of 5 ms is less than 1%, thus indicating that the applied algorithm (Fig. 4) provided acceptable labeling of MVC and MVO for our purpose.

Ground truth for valve events: LV dP/dtmax and LV dP/dtmin were used to define aortic valve opening (AVO) and aortic valve closure (AVC), respectively. Mitral valve closure (MVC) was found using the MICOR algorithm13. In this algorithm, two horizontal lines were draw 25% down from the peak point and 25% up from the minimum point as shown with the lines labeled (1). Subsequently, a diagonal line was drawn, connecting the bottom quadrant of the first beat’s LVP trace to the top quadrant of the subsequent beat’s trace (2). After establishing this diagonal line, the point that was furthest away from this diagonal line on the LVP trace was identified (3). This point served as MVC. From previous measurements in our animal model, mitral valve opening (MVO) occurs at similar pressure as MVC. Hence, MVO was found as the point where LVP during diastole decayed to the same pressure as MVC (4).

Automatic detection of valve events using deep neural network

Once the ground truth had been established, we applied our previously developed deep learning model8 to detect the opening and closing events of the aortic and mitral valves. In this model, we employed a combination of recurrent neural networks (RNN), convolutional neural networks (CNN), and an attention module to predict the precise timepoints for aortic valve events from accelerometer recordings. The model used the magnitude of acceleration to detect the valve events:

The model architecture remained identical for both aortic and mitral valve event detection, with only the annotation labels differing between tasks. Each accelerometer trace was processed in three stages: the CNN first captured short, local patterns in the waveform using sliding filters (136 ms receptive field, 16 ms stride), tuned to pick up the oscillatory signatures of valve motion. These local features were then passed to the RNN, which linked information across consecutive heartbeats to reflect the natural temporal structure of the cardiac cycle. Finally, the attention module helped the network selectively focus on the most informative parts of the signal, enhancing relevant features and suppressing background noise. Throughout, species classification was included as an auxiliary task to improve generalization and regularize training. To ensure the model captured general rather than animal-specific features, training and testing were performed using nested cross-validation, with each test fold composed entirely of animals unseen during training.

The model was trained using the AdamW optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001, weight decay set to 0.0001, and a batch size of 32. Batch normalization was used in the final configuration, and the model size was fixed to the scaling factor k = 1. Convolutional weights were initialized using He (Kaiming) initialization, RNN hidden states were initialized from a uniform distribution, and attention weights followed Xavier initialization. To improve generalization, data augmentation was applied by randomly sampling 3 s input segments and introducing variability through time warping and magnitude scaling (factors between 0.8 and 1.2). Early stopping was performed based on validation loss.

Event prediction was performed for each of the 136 ms sliding windows. To consolidate predictions into a single event estimate, we used a confidence-weighted density approach. Candidate event probabilities were re-scaled and averaged across windows, followed by a 60 ms moving average filter to suppress isolated false positives and emphasize high-likelihood regions. Final event times were determined by the peak of the filtered prediction density. Low-confidence predictions (score < 0.4) were excluded, and redundant detections within 300 ms of one another were resolved by keeping only the highest-scoring prediction. This post-processing ensured the accurate alignment of predicted events with physiological ground truth.

During the testing phase in each cross validation, the deep learning model’s detected valve event outputs were used to calculate the functional indices described below for the respective recordings, ensuring accurate evaluation where each event had been generated by the model. Only those beats where all four events were detected by the deep learning model were used for estimating the LVP trace and calculating the indices.

Estimating left ventricle pressure trace

Once accelerometer-timed valve events were identified for each heartbeat, LVP traces were estimated using pre-established methods developed by Russell et al.7,10. This involved adjusting the cardiac phases and magnitude of a reference LVP trace. To summarize, a reference LVP trace was first generated from all the baseline LVP traces. This was done by adjusting the four cardiac phases of each trace to the same prespecified durations using the ground truth valve event timings (Fig. 4) and normalizing their pressure amplitude to 1. The reference LVP trace was then generated as an average of these normalized traces.

Estimation of an LVP trace for a heartbeat in any animal during any intervention required the valve events detected by the deep neural network from the acceleration signal, and peak pressure (which in clinical practice would be set equal to brachial systolic cuff pressure or arterial systolic pressure if available). The individual LVP trace was then estimated using the reverse process: the reference trace’s amplitude was scaled to the measured peak pressure, and the durations of the four cardiac phases were adjusted to align with the detected valve events of the individual heartbeat.

Peak early systolic velocity (Vpeak)

Velocity can be estimated from the accelerometer signal by numerically integrating acceleration using the trapezoidal rule. Let x(t) represent the acceleration signal, where xj and xj+1 are consecutive samples and Δt is the time interval between samples. Then, the velocity at time ti is approximated as:

Signal drifting is a common problem when working with accelerometers. However, when applied to the heart, the mean acceleration over one heartbeat may be assumed to be zero as the accelerometer starts and ends at the same position if the patient is stationary and when ignoring respiratory motion. Following the detection of the valve events by the neural network, MVC events were used to segment the signal into heartbeats, and mean acceleration over one beat was subtracted before integrating to velocity:

where \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{x}}_{j}\) is the mean-centered signal, xj is the original signal at sample j, N is the number of samples in one heartbeat, and the summation term computes the average of the signal value across that beat.

Peak early systolic velocity in the circumferential direction was extracted as the maximum value within a 150 ms interval from MVC, as defined in previous publications14 (Fig. 6).

Post-systolic displacement (PSD)

Post-systolic displacement (PSD) was determined from the accelerometer y-axis, displaying circumferential LV motion. The circumferential displacement trace was calculated by integrating the velocity trace after subtracting mean velocity over each heartbeat, using the equations above. Post-systolic displacement was then defined as the displacement value at 100 ms following AVC minus the displacement value at AVC (Fig. 6). We set displacement to zero at MVC and defined positive and negative sensor-directions so that normal systolic circumferential displacement had increasing values and decreasing values when the sensor returned to its starting position during diastole. Hence, post-systolic displacement values were negative for normal motion, while a positive post-systolic displacement was indicative of paradoxical motion associated with ischemia.

Pressure-displacement loop area (PDLA)

Pressure-volume or pressure-strain loops are commonly used to obtain functional parameters. An accelerometer equivalent would be the pressure-displacement (PD) loop, combining the estimated LV pressure with the displacement trace (Fig. 6). A reduction of this loop area has been shown to be a sensitive marker of ischemia15.

Integration of the acceleration signal to velocity and displacement are shown in the top three panels and the estimated vs. measured left ventricular pressure traces are shown in the fourth panel with the resulting pressure-displacement loops in the bottom panel. The extraction of early systolic peak velocity (Vpeak), post-systolic displacement (PSD), and pressure-displacement loop area (PDLA) are indicated. Note that the PSD is negative (arrow pointing downward) in this case of normal motion, while in cases with paradoxical motion such as typical for ischemia, it will be positive and point upwards.

Pressure-displacement efficiency (Eff)

Abnormal motion patterns associated with ischemia may result in relatively low PDLA relative to the distance the sensor moves during a heartbeat as seen in bottom panel of Fig. 3. Hence, we extracted the pressure-displacement efficiency (Eff) index as:

This formula computes a measure of efficiency by comparing the value of the total area covered (PDLA) to the cumulative sum of the absolute circumferential displacements.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean (± SD) unless stated otherwise. To assess the impact of interventions on functional indices, a two-tailed paired t-test was used, comparing baseline values with recordings at the maximum effect of each intervention. To account for multiple measurements from each animal when using the Bland–Altman plots, reference intervals were displayed based on agreement between methods of measurement with multiple observations per subject16. For the correlation analysis, Pearson correlation coefficient was used. The statistical analysis was performed in Python 3.7.

Results

Valve event detection

The deep learning model was run on a total of 289 recordings. The performance of the model for aortic valve events has already been presented in a previous study8, but some results are included here for comparison with the mitral valve events. When pooling all interventions across both canines and pigs, the correct detection rates for MVO and MVC, defined as occurring within 40 ms of the true event, were 89.6% and 87.5%, respectively. The mean absolute error between the correct detections and their corresponding targets was 13 ms for both. The distribution of the detection errors for all four valve events is shown in Fig. 7. The details of the performance for mitral valve events during different interventions are given in Tables 1 and 2 for canines and pigs, respectively.

Estimated left ventricle pressure

There was a very good agreement between the estimated and measured LV pressure traces. For all 289 recordings spanning over almost 5300 heart beats (where all four events had been detected correctly out of 5900 beats), the limits of agreement were − 16 to 17 mmHg (Fig. 8). The correlation between pressure–displacement loop area using estimated vs. measured LV pressure traces was r = 0.97 (Fig. 9a). The mean difference was 30 (± 156 2SD) mm·mmHg (Fig. 9b).

Difference between estimated and measured LV pressure traces over time for different interventions. Each trace shows the mean difference for the specified intervention labeled by color. The duration of the 4 cardiac phases (vertical dashed lines) have been normalized for all traces. Abbreviations as in Tables 1 and 2.

Changes in parameters with interventions

To evaluate if the derived parameters can be used for monitoring cardiac function, we analyzed their response to different interventions. The pig studies had the most consistent protocols with the same interventions performed in most of the animals allowing investigation of meaningful statistical changes. The changes with interventions of the four extracted functional parameters all correlated well with changes in stroke work as seen in Fig. 10.

Table 3 shows the response of hemodynamic parameters together with the four extracted accelerometer indices for each intervention from two previous pig studies5,17. Ischemia showed marked reduction in early systolic velocity and pressure-displacement loop area. A notable paradoxical motion with a positive post-systolic displacement was seen and the efficiency index was halved. Esmolol showed a less marked reduction of the velocity and loop area. The efficiency index was non-significantly reduced and on average there was no paradoxical post-systolic displacement. Loading only significantly increased loop area, while the somewhat greater unloading effect on EDV reduced velocity and loop area, and post-systolic displacement became less negative, all signs that general motion was reduced.

Discussion

In this study we have shown that timing of mitral valve closure and opening can be detected with reliable precision using a deep neural network applied to signals from an epicardially attached accelerometer. We have also showed how automatic detection of mitral and aortic valve events allows extraction of functional indices from the signals, which has the potential of improving cardiac function monitoring by making it more autonomous and robust.

We utilized the detected events to automatically extract peak early systolic velocity and post-systolic displacement, and to estimate LV pressure in order to generate the pressure-displacement loop area and efficiency index. All these four markers correlated well with changes in LV stroke work. We have previously used R-peak detection to extract peak early systolic velocity and showed how it was reduced by ischemia15. This was consistent with this study where MVC was used instead of ECG R-peak. Post-systolic shortening is another hallmark feature of ischemia, but we have not been able to automatically extract the accelerometer equivalent of post-systolic displacement previously. However, the automatic detection of aortic valve closure now facilitated automatic extraction of post-systolic displacement which was shown to distinctively change with the paradoxical ischemic motion. In a previous study we extracted PDLA using invasively measured pressure and showed it to be a highly sensitive marker of ischemia7. As invasive measurement of LV pressure is not available in clinical routine, we estimated the LV pressure trace based on the detected valve events as an alternative, and showed similar PDLA reduction in response to induced ischemia. We also derived the novel loop area efficiency index, which was also significantly reduced by ischemia. Generally, different indices have their own pros and cons and will reflect different aspects of the underlying function. Thus, different pathologies may be detected with different indices depending on which is most sensitive for each. In clinical decision making, it is also common to look at several indices in combination, but developing such algorithms were outside the scope of this study. Importantly, the study demonstrates how such indices can be generated and analyzed in real-time, allowing for immediate adjustments to therapy based on the observed changes in cardiac function.

Valve events were detected by the neural network using only accelerometer signals, eliminating the need for ECG or any additional signals, thereby simplifying heart monitoring and reducing hardware requirements. The accelerometer signal alone sufficed to generate cardiac function indices, enabling beat-to-beat cardiac monitoring without supplemental tools. The method was applied to a diverse dataset encompassing recordings from four different protocols conducted over 15 years. The variations in personnel, different prototype packaging designs of accelerometer over the years, two experimental species, experimental protocols with numerous different interventions under both closed and open chest settings, provided heterogeneous data with highly varying function and motion. Despite this extensive variability and complexity of the dataset, the deep learning model exhibited robustness in detecting valve events. This demonstrates the ability of the utilized deep neural network architecture to recognize patterns in the acceleration signal and learn generalised features.

Reference annotation of mitral events in a large number of beats is required for training and testing a deep learning model. To achieve this, we used only LVP and the MICOR method to determine MVC and then assumed the pressure at MVO to be identical to the pressure at MVC. In this manner the annotation process was automated, but it may not have been as accurate as if more sophisticated measurements had been available to determine the events. In the subset of animals where MVC and MVO could be determined manually with more comprehensive measurements, these agreed quite well with the automatic annotation method. As this was validated in a limited subset, we cannot exclude that errors were present in some other cases. However, the automatically detected valve events were applied to estimate the LV pressure curve in all the data. The accuracy of this estimation indicates that potential errors in annotation or detection were not a major problem. To further enhance the detection rate, a more accurate annotation method could be crucial. Generally, a model’s performance depends on both quality and quantity of its training data. In some interventions with few cases, accuracy was poor. Obtaining more data may therefore be an important factor in improving performance across the entire physiological range of cardiac function. Translating this method to humans presents challenges, such as collecting invasive pressure and volume data along with simultaneous accelerometer recordings from a sufficient number of patients to annotate valve events and train the model. An alternative approach could be to use imaging to capture valve events. Our model was trained on relatively short input sequences of 3 to 5 s, containing only a few heartbeats each. Thus, recording and annotating such short imaging sequences in patients with cardiac accelerometers would be feasible. The deep neural network architecture performed well in both pigs and canines, and for mitral and aortic valve events. This suggests that the accelerometer detects and records physiological information about valve events which can be extracted using the presented methods, and demonstrates the potential for human application.

A limitation of our study was that we set the peak systolic value of the estimated LV pressure trace to the measured peak pressure. This will not be available in clinical practice and should hence be estimated as systolic brachial cuff pressure or peak arterial pressure if available. Therefore, the results involving this pressure estimate, may have been somewhat idealized. The valve event detection uses acceleration magnitude which means that there is no need to align the three accelerometer axes with the cardiac coordinate axes, making the attachment of the accelerometer to the myocardium easier. However, the motion indices used in this study were extracted along the circumferential acceleration of the heart, which will require the alignment of axes during implantation. A potential next step will therefore be to find sensor orientation independent functional indices.

Conclusion

Deep neural networks can robustly detect mitral and aortic valve events solely from signals recorded by a three-axes accelerometer attached to the LV epicardium. This facilitates automatic extraction of functional indices from specified phases during the cardiac cycle. The study demonstrated how four such indices could be automatically extracted and reflected changes in cardiac function during specified interventions. These steps are important for transitioning this technology to enable continuous and autonomous monitoring of cardiac function in humans.

Data availability

Data presented in this study is available at https://doi.org/10.13026/5xmr-zd88. Corresponding author Espen Remme can also be contacted concerning data requests.

References

Bugge-Asperheim, B., Leraand, S. & Kiil, F. Local dimensional changes of the myocardium measured by ultrasonic technique. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 24, 361–371 (1969).

Waldman, L. K., Fung, Y. C. & Covell, J. W. Transmural myocardial deformation in the canine left ventricle. Normal in vivo three-dimensional finite strains. Circ. Res. 57, 152–163 (1985).

Senoner, T. et al. Long-term performance of an atrial lead capable of accelerometer-based detection of cardiac contractility in patients receiving cardiac resynchronisation therapy. PLoS One. 14, e0222269 (2019).

Chinitz, L. et al. Accelerometer-based atrioventricular synchronous pacing with a ventricular leadless pacemaker: results from the Micra atrioventricular feasibility studies. Heart Rhythm. 15, 1363–1371 (2018).

Halvorsen, P. S. et al. Detection of myocardial ischaemia by epicardial accelerometers in the pig. Br. J. Anaesth. 102, 29–37 (2009).

Vincent, J. L. et al. Clinical review: update on hemodynamic monitoring - a consensus of 16. Crit. Care. 15, 1–8 (2011).

Wajdan, A. et al. Automatic detection of valve events by epicardial accelerometer allows Estimation of the left ventricular pressure trace and pressure–displacement loop area. Sci. Rep. 10, 20088 (2020).

Wajdan, A. et al. Automatic detection of aortic valve events using deep neural networks on cardiac signals from epicardially placed accelerometer. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 26, 4450–4461 (2022).

Wajdan, A. et al. Epicardially attached cardiac accelerometer data from canines and porcines (version 1.0.0). PhysioNet https://doi.org/10.13026/5xmr-zd88 (2023).

Russell, K. et al. A novel clinical method for quantification of regional left ventricular pressure–strain loop area: a non-invasive index of myocardial work. Eur. Heart J. 33, 724–733 (2012).

Remme, E. W. et al. Mechanisms of preejection and postejection velocity spikes in left ventricular myocardium: interaction between wall deformation and valve events. Circulation 118, 373–380 (2008).

Aalen, J. M. et al. Mechanism of abnormal septal motion in left bundle branch block: role of left ventricular wall interactions and myocardial Scar. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 12, 2402–2413 (2019).

Brennan, E. G. & O’Hare, N. J. Calibration and assessment of a fluid-filled catheter-transducer system for the measurement of ventricular diastolic pressures. Physiol. Meas. 19, 405 (1998).

Wajdan, A. et al. Monitoring cardiac function by accelerometer-detecting start systole from the acceleration signal makes additional ECG recordings for R-peak detection redundant. In 41st Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC) 4922–4925 (2019). (2019).

Halvorsen, P. S. et al. Automatic real-time detection of myocardial ischemia by epicardial accelerometer. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 139, 1026–1032 (2010).

Bland, J. M. & Altman, D. G. Agreement between methods of measurement with multiple observations per individual. J. Biopharm. Stat. 17, 571–582 (2007).

Krogh, M. R. et al. Continuous Estimation of acute changes in preload using epicardially attached accelerometers. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 68, 2067–2075 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.W., M.V.M., P.S.H., O.J.E. and E.W.R. participated in data collection. A.W. and V.C.F. conducted the data analysis and wrote the manuscript text together with E.W.R. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

P.S.H., O.J.E., and E.W.R. are patent holders of the accelerometer technology for assessing cardiac function and are shareholders in Cardiaccs A/S which is commercially exploiting this technology. A.W. and V.C.F. declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wajdan, A., Frostelid, V.C., Villegas-Martinez, M. et al. Deep neural network valve detection for accelerometer based cardiac monitoring. Sci Rep 15, 17419 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00845-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00845-2