Abstract

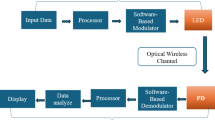

Visible Light Communication (VLC) is a breakthrough technology, enabling a new type of wireless communications in both indoor and outdoor. For the first time, here we achieve VLC transmission in indoor by combining a new and innovative, large-Field of View (FoV) receiver with commercial high-power white Light Emitting Diodes (LEDs). After careful characterization and optimization of the devices, we assess the system performance by Bit Error Ratio (BER) measurements. Then, in a realistic configuration, we perform several transmission tests. We transmit a real-time 10 Mbit/s HD video stream. Finally, mixed-color white LEDs are also shown to be instrumental in improving the performance. Our work paves the way to the deployment of the proposed solution in real scenarios.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Light Emitting Diodes (LEDs), besides their conventional use for illumination, can be effectively used for Visible Light Communication (VLC). Differently from RF communications, VLC technology can provide significantly higher data rates and can enable Internet access in RF-restricted areas1. It leverages visible light, allowing user mobility by either using Diffused Non Line of Sight or Non-directed Line of Sight configurations1,2,3. The latter configuration is the most frequently considered: it exploits wide-angle Transmitters (TXs) and large Field of View (FoV) Receivers (RXs)4, so that it offers a good trade-off between robustness and link capacity. However, it typically uses large-area photo-diodes, resulting in a high parasitic capacitance, which reduces the available bandwidth (BW)5.

As an up-and-coming solution to this bottleneck, it was recently proposed to exploit a combination of planar Luminescent Solar Concentrators (LSCs) and small-area photodiodes; this can be a RX having both large-BW and large FoV6,7,8. LSCs were initially developed for solar energy harvesting. Recently, they have been also proposed in VLC systems, where they can represent a remarkable opportunity to realize a photovoltaic window with VLC capabilities9. In this case, a fluorescent planar waveguide is realized by dispersing fluorophores in a glass or plastic poly methyl-methacrylate substrate. The fluorophores convert part of the impinging light, then re-emit it as fluorescence light, Stokes-shifted towards the red portion of the visible spectrum10. Thanks to the difference in the refractive index of the slab and the air, a large portion of the fluorescence photons are waveguided towards the thin edges of the slab, where a small-area photodiode is placed. The slabs should be realized in wide-area configuration, and we should properly select fluorophores that feature low reabsorption9,11, also with tailored geometries and internal structures. LSC and standard photodiodes, unlike traditional receivers, can be effectively combined to develop optical antennas that offer significant advantages, such as a broad field of view and an enhanced optical gain, without sacrificing the receiver bandwidth. For efficient VLC receivers, balancing high optical gain with broad bandwidth is a crucial goal. Large-area photodiodes are sometimes recommended for their high optical gain, yet they have significant parasitic capacitance, which limit the bandwidth: this becomes a bottleneck in VLC systems needing both high gain and wide bandwidth. Several techniques, such as the reconfigurable intelligent surfaces (RISs) and liquid crystals12,13, are proposed in wireless communication with the aim of enhancing the signal quality, optimizing the propagation path. This solution, although quite promising, comes with drawbacks. As an example, both types of devices require to continuously control the voltage to adapt the beam to a new scenarios (e.g., movement of the VLC-RX), with a slow tuning time.

An alternative solution involves combining a photodiode with small-area, which naturally supports high bandwidth due to low parasitic capacitance14, with optical condensing elements, e.g., biconvex lenses, fisheye lenses, Fresnel lenses15,16. These traditional components focus the light onto the small-area Photo-Diode, thereby increasing the collected optical power (of course, the electrical bandwidth is unaffected). However, these condensing elements are governed by geometric optics and thus face the key limitation that the field of view reduces as optical gain rises, due to étendue conservation; unfortunately, this is an unacceptable price for practical VLC systems. Recently, 2D-steered stencil beams were proven to support high bandwidth and some degree of user mobility17. This solution can provide very high capacity, although it introduces a complex system; the beam steering is realized by tunable transmitters and precise active alignment, which also requires fine-tuning of the lasers.

LSC-based systems can also provide a very large optical gain, exceeding orders of magnitude that of a receiver based on a lens with similar FoV (e.g., \(120^{\circ }\))6: this is achieved while maintaining the large BW of a small size Photo-Diode. Clearly, this solution might also be combined with RIS or LSC solutions, ensuring robustness against misalignment and optimizing the propagation. In this scenario, the lifetime of fluorophore excited states is a critical parameter, posing an upper limit to the attainable BW. Both organic and quantum-dot based fluorophores can feature lifetimes in the few ns to \({\upmu }\)s range18, and VLC communications featuring 190 Mbit/s7 and 2.1 Gbit/s19 rates were recently demonstrated, employing On-Off Keying (OOK) and Optical Frequency Division Multiplexing with Quadrature Amplitude Modulation (QAM) schemes, respectively. However, most of the available literature either exploits blue LED sources (to maximize the antenna absorption), low-power fast laser sources20 (with high modulation BW), or efficient yet complex multiple-input and multiple-output schemes21 to improve the overall throughput. All these approaches are hardly adequate for a massive deployment of VLC applications in real-world scenarios, where high-power white LED sources are largely employed.

Few recent works tackled this issue, obtaining VLC with white LEDs and Fluorescent Concentrator (FC)-based RXs. A multilayer FC system was reported by Manousiadis et-al in22, using Wavelength Division Multiplexing signals in the blue and in the green regions. In23, a preliminary design using three distinct fluorescent fibers, which selectively absorb different wavelength ranges, was presented. Meanwhile, a very recent work reported a comparative analysis of fluorescent antennas for white light VLC applications based on LSC24. However, there is still a gap in the demonstration of FC-based optical antennas in realistic VLC configurations, embedding ordinary high-power white LED sources.

In this work, we fill this gap and report the first demonstration of a complete VLC system in a real scenario that exploits white LED and large FoV FC-based RXs. To reach this goal, we carefully optimize all parts of the system. Namely, in order to improve the FoV and detection area, we use a new slab with FC and sided Photo-Diode. In particular, we exploit one of the most efficient organic fluorophore for LSC application, featuring large BW and good absorption properties (Lumogen© Red 305F (LR305)24). Furthermore, we remove the blue filter at the RX to fully take advantage of the high optical gain potentially provided by the FC slab; this is made possible by introducing a new pre-distortion electrical filter at the TX.

After preliminary measurements, we demonstrate the system using a high-power commercial white-LED at the ceiling (TX) and our novel RX. We deeply characterized the VLC system in a realistic configuration. This confirms the high performance of our system both in terms of Signal to Noise Ratio (SNR) and FoV as compared to an ordinary Photo-Diode-based RX stage. As key application, we demonstrate a real-time VLC transmission of 10 Mbit/s High-Definition (HD) video through Ethernet protocol, proving the full compatibility of the solution with a established protocol. Finally, in order to test the potential of our approach, we also used Discrete Multi-Tone (DMT) modulation to enhance the achievable data rate in our system and we also investigated the performance of our system when a Red-Green-Blue-White (RGBW) LED is used as TX source, featuring a larger BW.

This paper is organized as follows: in the Sect. “Experimental setup and characterization of device”, we present and discuss the selected optical sources and the novel LSC. We describe the experimental setup and report the characterization of the devices. In the Sect. “System performance: transmission results”, we present and discuss the results of the transmission experiments: we first analyze our VLC system with a 10 Mbit/s OOK signal—Ethernet 10Base-T like—in terms of Bit Error Ratio (BER). Then, we demonstrate a HD video transmission over 2 m distance. We also test the setup by exploiting an advanced modulation format to improve the data rate in a more realistic scenario, where the optical source is placed on the ceiling. Finally, the conclusion and future works are discussed in the Sect. “Conclusion”.

Experimental setup and characterization of devices

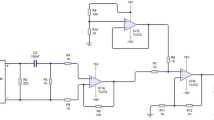

We present the experimental setup for the VLC characterization and data transmission in Fig. 1. At the TX side, the electrical signal can be generated using an Arbitrary Waveform Generator (AWG) or a Field Programmable Gate Array (FPGA), depending on the measurement to be performed. The electrical signal is equalized by an optimized analog equalizer, which pre-compensate for the limited LED BW: we highlight that this removes the need to have a blue filter at the RX. This is an important feature, as the filter limits the FoV (it has a limited operating range of input angles). The signal is amplified by a power amplifier (27 dB gain, 120 MHz 3 dB BW).

In the reported measurements, we use two different LED sources: a 7-White-LED (WLED) array and a 4 chips RGBW LED. The first is a common LED type, whilst the second is used to test the limits of the system. The optical source is driven by a modulated current signal, externally biased to provide for the nominal LED bias current. After a 2 m free-space propagation, the optical signal is received by the optical sensor, consisting of a LSC planar waveguide with a thin edge coupled to an Avalanche Photo-Diode (APD) placed in the middle of one of its side. The collected optical signal is converted, amplified, and analyzed by means of a Real-Time Oscilloscope (RTO), an Electric Spectrum Analyzer (ESA), or the FPGA, depending on the measurement. The following sections describe the optoelectronic subsystems realized as RX and as TX.

(a) Experimental setup for the characterization of the devices and for the communication measurements. AWG: Arbitrary Waveform Generator; LED: Light Emitting Diode; FPGA: Field Programmable Gate Array; ESA: Electric Spectrum Analyzer; RTO: Real-Time Oscilloscope; (b) Detail of the LSC-based RX stage.

Receiver

Our RX included a \(50\times 50\) mm2 planar LSC slab with 3 mm thickness. The slab is embedded with a 3 mm diameter Si-APD chip, placed at the central point of one edge of the slab, and a Transimpedance Amplifier (TIA) stage (Hamamatsu C12702-04) (0.004–80 MHz band-pass BW and \(2\times 10^{4}\) V/W photoelectric sensitivity). The RX is shown in detail in Fig. 1b, where we can see the LSC, the photodiode and the TIA. The TIA stage is AC-coupled to the second amplifier section in order to reject unwanted low-frequency components due to the background ambient light sources. This approach is generally sufficient in indoor configurations, whilst more complex AC decoupling schemes could be chosen at the photodiode-TIA interface in outdoor, where the receiver can be exposed to strong solar irradiance11. The electrical signal was further amplified by a Dynamic High Power Voltage Amplifier (DHPVA) (FEMTO, 200 MHz BW, 30 dB gain) to obtain a suitable voltage output. We fabricated the slab by dispersing LR305 fluorophores (concentration of 350 ppm) in a PMMA matrix, optically polished to allow for efficient total internal reflection of the emitted fluorescence24. We selected the LR305 fluorophore thanks to its particularly favorable absorption and emission properties tailored to LSC applications, and a large quantum yield value (\(\phi\) = 0.83 for the slabs).

For the sake of clarity, we report in Fig. 2 the absorption (blue curve) and emission (red curve) spectra of the LR305 together with the emission spectra of the two optical sources used at the TX: a WLED (Fig. 2a) and a RGBW LED (Fig. 2b). As we see, the absorption spectrum of the LSC starts at 400 nm (violet line) and ends at around 610 nm (red-orange line), so that the red light is not absorbed by the LSC. In the case of a WLED (yellow trace in Fig. 2a), the absorption has a remarkable spectral overlap with both the blue component (~461 nm) and green-yellow emission of the phosphors (~520–610 nm) that determine the white emission of the phosphor LED. Noteworthy, the LSC also provides a good Stokes shift (37 nm) in the emitted fluorescence; this allows limiting the number of re-absorption processes, which might hamper the antenna efficiency and bandwidth18. Clearly, a larger Stokes shift is desirable; however, re-emitting red light is the best option currently available. Although other organic fluorophores, such as quinoxaline DQ-125, feature larger Stokes shift and slightly larger \(\phi\), LR305 spectral properties recently made it one of the best candidates in VLC applications embedding white phosphor-based LEDs24, thanks to the large overlap. Such overlap is less optimal in the case of the RGBW LED sources (green trace in Fig. 2b), as the red emission line would not be absorbed by LR305. In our measurement, the information is conveyed and boosted on the green and blue wavelength lines only, while the red and the white LED chip sources are just biased, in a color mixture conceived to render a good white outcome. Therefore, we expect WLED to perform better than RGBW in terms of pristine conversion efficiency. However, when using RGBW, we can attain a larger BW than with WLED (see next section): this can play a crucial role when optimizing the capacity of the link. We notice that, in this present version of the RX, a portion of the fluorescence light escapes from the uncovered portion of the slab edges. However, the large ratio between the LSC collection surface and the thin edges surface intrinsically boosts the attainable overall optical gain of the LSC-based optical angenna even considering the intrinsic photon losses through the escape cone of the LSC26. In the future, the collection efficiency could be further improved and optimized according to various strategies, e.g, by adding a reflecting coating on the uncovered portion of the edges, or by adding multiple photodiode elements, one at each edge. This might also allow to make the LSC smaller.

We also measured the electrical BW using an ESA and a fast laser source at 405 nm, modulated with a sinewave sweeping from 1 to 50 MHz. The resulting BW, reported in Fig. 2c, is around 15 MHz, mainly limited by the lifetime of the LR305 optical re-emission (\(\sim\) 8 ns) and re-absorption processes. We note that this value is fully compatible with the considered scenario; there, the modulation bandwidth of a typical high-power LED source is around 10–20 MHz, thus the bandwidth of the implemented receiver does not need to be higher than 15 MHz.

(a) Optical spectra of the WLED (emission spectrum, yellow) and the LSC Lumogen (absorption spectrum, blue and emission spectrum, red). (b) Optical spectra of the RGBW LED (emission spectrum, green) and the LSC Lumogen (absorption spectrum, blue and emission spectrum, red). (c) Frequency response of the proposed RX. The value indicates the 3 dB BW.

Transmitter

The electro-optical characteristics of the VLC TX are crucial in defining the performance of the communication system. We will discuss these deeply in the following.

The WLED source is a cool white Phosphor LED (Ph-LED) array of 7 chips. We supplied the LED with a bias current of 300 mA and it generated an on-axis illuminance of 318 lx and of 77 lx at the distances d of 1 m and of 2 m, respectively. Commercial Ph-LEDs typically have a BW of few MHz, which is typically enhanced by using a blue filter in front of the RX to reject the slow phosphors components27. However, this technique reduces the SNR, due to a lower received optical power (approximately two third lower), the filter also strongly limits the FoV. We thus did not use the filter and addressed the BW issue by developing a linear passive equalizer at the TX. This equalizer pre-distorts the transmitted signal to pre-compensate for the attenuation caused by the parasitic capacitance in the high-power LEDs: therefore, we obtained a flat frequency response. The effect of using the proposed equalizer can be seen in Fig. 3, where we report the measured BW of the WLED, without and with the equalizer: the frequency responses were measured by driving the LED with a sinusoidal input sweep (up to 30 MHz) from the AWG, and using a bare high-speed APD as a photodetector. Clearly, in the two configurations, we kept the same electrical power at the TX. From the ESA output, we see that the 3 dB BW increases from 2.9 to 5 MHz. Moreover, the steepness is strongly reduced thanks to the equalizer: without the equalizer, we see a 10 dB/decade frequency attenuation that decreases to 3 dB/decade with the equalizer.

As said, these measurements were taken with a fast Photo-Diode (280 MHz): if we consider the real RX, the overall BW is only slightly lower and approximately 4.5 MHz with a slightly higher roll-off of 5 dB/decade.

We performed a similar experimental analysis on the RGBW LED. This source consists of four chips, three are monochromatic chips (red, green, and blue) and the fourth one is a Ph-LED. Each chip is supplied to obtain an overall white light output. To this aim, the supply current values are 430 mA, 450 mA, 200 mA, and 250 mA for the red, the green, the blue and the white chips, respectively. We characterized this source, since it presents a significant benefit in terms of electrical BW, which is usually higher than in Ph-LEDs. Similarly to the WLED characterization, we measured the electrical 3 dB BW with and without the same passive equalizers applied on the green and on the blue LED chip sources, still keeping the same electrical power in the two configurations. This resulted in an overall 3 dB BW of 6.2 MHz and of 42.8 MHz, without and with the equalizer, respectively. As we see in Fig. 3b, the equalizer mitigates the roll-off (i.e., again it flattens the frequency response). In the case of the equalized RGBW LED source, we can notice a minor peaking response at about 23 MHz. As for WLED source, there is still some room for a (limited) enhancement of the system.

(a) Frequency responses of the WLED with (red curve) and without (brown curve) the equalizer. (b) Combined frequency responses of the two modulated channels (green and blue) of the RGBW LED with (green curve) and without (black curve) the passive equalizer. In both figures, we explicitly indicate the 3 dB BWs for the various cases.

System performance: transmission results

We evaluated the transmission performance of the proposed VLC system. A key requirement is the compatibility with the existing network solutions; to this aim, we chose to transmit a signal compatible with the Ethernet protocol, widely used in indoor local area networks. For the system characterization in terms of BER, we used a Manchester-encoded 10 Mbit/s OOK signal, which is physically equivalent to the 10Base-T Ethernet. Subsequently, we established a point-to-point Ethernet link and transmitted an HD video between two Personal Computers, utilizing the VLC system as a wireless bridge. Then, a series of measurements were conducted to evaluate and to optimize the system performance. To this aim, we tested the two optical sources (WLED and RGBW LEDs) with a DMT modulation format that maximizes the bitrate, given the available SNR.

10 Mbit/s OOK Manchester

The characterizations presented previously suggest the feasibility of a transmission using a BW up to 20 MHz, thanks to the equalized response. To assess the actual performance, we used the experimental setup illustrated in Fig. 1: we employed an FPGA at both the TX and the RX ends. The FPGA was generating, receiving, and performing the BER measurements of the 10 Mbit/s Manchester-encoded OOK signal. The bit-rate and the coding were selected to emulate a 10Base-T Ethernet signal (10 Mbit/s Manchester-encoded). Initially, we performed the BER measurements varying the optical irradiance at the RX to determine the system sensitivity. The results are reported in Fig. 4a. The linear trend (on a double logarithmic scale) shows a sensitivity of \(-16 \hbox { dBm/cm}^{2}\) at the BER target of \({10^{-9}}\). We emphasize that this sensitivity value is not optimal because, as mentioned earlier, the RX is not yet optimized, and most of the collected power is lost from the uncovered sides of the slab. This notwithstanding, we can still appreciate the improvement provided by the LSC compared to conventional solutions: we also report the BER taken using a blue filter before the bare APD, without the LSC (shown with black squares in Fig. 4a). In this last case, we can clearly see that, at the same irradiance value, the BER increases to \({10^{-3}}\).

Yet the key feature of our solution is the large FoV: to demonstrate it, we repeated the BER measurements by varying the Angle of Incidence (AoI) values. The results are presented in Fig. 4b. From the comparison, it is clearly evident that the bare APD (blue dots) curve shows a saturation at \(8 \times 10^{-4}\) in the aligned condition (i.e., AoI = \(0^{\circ }\)), whilst the green squares indicate a \(\textrm{BER}<{10^{-9}}\) from AoI = \(0^{\circ }\) up to \({20}^{\circ }\), after which it rises up to 0.5 at an AoI = \({90^{\circ }}\).

HD video demonstration

For the experimental scenario of the HD video transmission, we have realized an indoor horizontal VLC link of \(d = {2}{\hbox { m}}\) (see Fig. 5a), which is a typical ceiling-desktop distance. The TX consisted of a Personal Computer generating the 10 Mbit/s HD video bitstream, which was uni-directionally transmitted using 10Base-T Ethernet User Datagram Protocol (20 MHz BW). We took the signal directly from the network card interface, pre-distorted by the equalizer and amplified, then sent it to the LEDs. On the other side, the output signal from the RX was first amplified by a DHPVA; the electrical signal is then conveyed via a cable to the Ethernet card of another Personal Computer, which demodulates and decodes the signal and plays the HD video on its monitor in real-time. A picture of the VLC link setup is shown in Fig. 5a.

As a proof of the successful transmission, we report in Fig. 5b a frame of the video stream and the RX with the LSC (in red). In Fig. 5c we report the eye diagram taken by a RTO. As it can be seen, the eye is not completely open, mostly due to residual intersymbol interference related to the combined limited BW of both the TX and the RX stages. We emphasize that the Ethernet signal consists of data packets along with some empty packets, since the HD video does not utilize the full capacity. Hence, there are idle states (between packets) present in the Ethernet signal, which can be seen as a horizontal line at the center of the eye diagram. Therefore, this line should not be mistaken for error bits.

(a) Picture of the video demonstrator setup. (b) Detail of the RX in the HD video demonstration. (c) Eye diagram of the Ethernet signal at the RX taken at \(d={1} {\hbox { m}}\). The horizontal line at the center of the eye diagram is the idle state of the Ethernet signal, therefore it should not be misled as error bits.

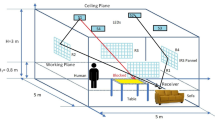

DMT—high power white LED

In order to test the maximum potential of the system, we tested it using DMT modulation. The realized link emulates a more realistic configuration: as sketched in Fig. 6a, the optical source was mounted at the ceiling and the RX mounted (on axis) on a tripod at the height of 90 cm, as shown in Fig. 6b. The vertical distance h between TX and RX was 2.1 m. To assess the benefits of the FoV, we moved the RX at different radial positions \(\rho\) ranging from \(-2.5\) to 2.5m with respect to the central axial position, with illuminance level at the RX varying from 60 to 25 lux, approximately. In these measurements, the RX was always pointing upwards, as shown in Fig. 6c. When we analyzed the system performance in terms of BER, we considered the region where BER \(<{3.8 \times 10^{-3}}\), because this is the usual limit for Forward Error Correction (FEC)28.

The DMT waveform consisted of 128 subcarriers allocated in a bandwidth of 25 MHz (around 0.2 MHz carrier spacing). The signal waveform was obtained by a homemade MATLAB tool running on a common PC; then it was uploaded to the AWG (see Fig. 6a) producing the electrical DMT signal. First, we estimated the SNR at the channel frequencies by using a DMT signal where all the subcarriers were modulated with Binary Phase Shift Keying (BPSK) of equal power (as explained in29). We then determined the SNR from the Error Vector Magnitude of the received constellation, following the method outlined in30. The upper part of Fig. 7a reports the SNR versus frequency from 0 to 25 MHz at \(\rho ={0}\) m (on-axis). Similar curves are collected at each \(\rho\) position.

Based on SNR estimation, bit and power loading algorithm was then applied to the subcarriers to adapt the individual loading to the channel response at each specific frequency31. The corresponding distribution of bit and power loading is reported in the lower part of Fig. 7a. The algorithm effectively adapts to the channel SNR by exploiting the available bandwidth to maximize the overall throughput. The bit per symbol increases at higher SNR values, and viceversa. The power distribution shows a saw-tooth behavior: in order to uphold the same QAM level within a set of adjacent subcarriers at the same BER, the power assigned to that group varies with the frequency following the inverse of the SNR curve. Subcarriers with a SNR of 15 dB are allocated a maximum of 16-QAM. The BER was measured after offline demodulation of all the DMT frames, each composed of approximately 2 Mbit.

Figure 7b,c show the constellation diagrams for the different QAM orders at \(\rho ={0}\) m (on-axis, Fig. 7b) and \(\rho ={2.5}\) m (Fig. 7c). The constellations, ranging from 16-QAM to BPSK, can be clearly identified. Depending on the distance, a different number of samples for each QAM order is present.

In Fig. 8, we report the maximum achievable data rates as a function of \(\rho\). As expected, the results show a symmetric behavior around \(\rho ={0}\) m. A maximum of 71 Mbit/s is achieved at \(\rho ={0}\) m with a total BER \(<3.8{\times }10^{-3}\), while at 2.5 m we can still achieve 25 Mbit/s, ensuring this data rate in an area of around 20 \(\textrm{m}^{2}\).

(a) WLED SNR and distributions of bit and power loading Vs frequency at \(\rho\) = 0 m (on-axis). (b) WLED constellation diagrams for the different QAM orders at \(\rho\) = 0 m (on-axis). (c) WLED constellation diagrams for the different QAM orders at \(\rho\) = 2.5 m. The constellations were taken at constant BER.

DMT—RGBW LED

Finally, we carried out an assessment test changing the source and using the RGBW LED. This was done to check the possibility to maximize the bitrate. In this experiment, the blue and the green LED chips were connected in parallel and all modulated together synchronously by a single DMT signal. Since the available electrical bandwidth was higher compared to the WLED configuration, as demonstrated previously, the DMT consisted of 128 subcarriers in a bandwidth of 40 MHz (around 0.3 MHz carrier spacing). For a fair comparison, as the emitted optical power of the RGBW LED is quite lower compared to the 7-chips WLED, we performed the measurements on the bench, fixing the transmission distance in order to obtain the same illuminance level as the WLED measurements (60 lx). Thus, in this measurement, the transmission distance was 1.2m. The measured SNR versus frequency from 0 to 25MHz at \(\rho = {0}\) m (on-axis) is reported in the upper part of Fig. 9a. The corresponding distribution of bit and power loading is reported in the lower part of Fig. 9a. Figure 9b shows the constellation diagrams for the different QAM orders at \(\rho ={0}\) m (on-axis).

We measured an aggregated throughput of 110 Mbit/s with the acceptable BER of \({3.2 \times 10^{-3}}\), under an illuminance level of approximately 70 lx. This result suggests that a roughly 50% improvement in the capacity can be achieved by exploiting high power and larger bandwidth optical sources.

We note that these measurements could be further optimized, as we expect to achieve higher data rates using RGBW LED sources with DMT modulation on some appropriate chip LEDs and the RX given by a fast APD in combination with a dedicated LSC.

Conclusion

We introduced a novel VLC system that combines a custom LSC with high-power white LEDs, testing its performance in a realistic indoor scenario. This innovative method largely improves the FoV, thus it enables achieving a high SNR at the receiver even without perfect alignment between the TX and RX. This is obtained thanks to the characteristics of LSC materials such as high optical gain and a wide FoV. By implementing proper pre-equalization at the TX, the system does not need a blue filter and maintains, at the RX, a BW high enough to support the transmission of a Manchester-encoded Ethernet signal at 10 Mbit/s. The devices in this VLC system were initially characterized individually, focusing on frequency responses and optical spectra. Subsequently, we assessed the system performance in terms of BER and we demonstrated a unidirectional transmission of a HD video at 2 m distance. To assess the potential in terms of transmission speed, we then used the DMT modulation, which adapts the bitrate to the available SNR and maximizes the same bitrate. This analysis was performed using two different optical sources: a high-power WLED and a RGBW LED. We recall that, in the latter case, we modulated only two (the blue and the green) of the four chips, as the red wavelength is not absorbed by the LSC. We thus obtained a bitrate of 70 Mbit/s for the WLED and of 110 Mbit/s for the RGBW LED, at the limited illumination level of 60 lx. 25 Mbit/s are guaranteed within an area of 20 \(\textrm{m}^{2}\) with the high-power WLED, again thanks to the high FoV tolerance.

Our work represents a significant step forward, towards the full deployment of VLC technology in real indoor environments, exploiting the effective combination of accurate pre-distortion, the removal of a blue filter and an innovative, high BW, large-area optical RX based on LSCs.

Data availability

The article includes all the data generated during this study.

References

Cossu, G., Corsini, R. & Ciaramella, E. High-speed bi-directional optical wireless system in non-directed line-of-sight configuration. J. Lightwave Technol. 32, 2035–2040 (2014).

Kahn, J. M. & Barry, J. R. Wireless infrared communications. Proc. IEEE 85, 265–298 (1997).

Seminara, M., Meucci, M., Tarani, F., Riminesi, C. & Catani, J. Characterization of a VLC system in real museum scenario using diffusive led lighting of artworks. Photon. Res. 9, 548–557. https://doi.org/10.1364/PRJ.414394 (2021).

Gfeller, F. R. & Bapst, U. Wireless in-house data communication via diffuse infrared radiation. Proc. IEEE 67, 1474–1486 (1979).

Nabet, B. Photodetectors: Materials, Devices and Applications. Woodhead Publishing Series in Electronic and Optical Materials (Elsevier Science, Berlin, 2023).

Collins, S., O’Brien, D. C. & Watt, A. High gain, wide field of view concentrator for optical communications. Opt. Lett. 39, 1756–1759. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.39.001756 (2014).

Manousiadis, P. P. et al. Wide field-of-view fluorescent antenna for visible light communications beyond the étendue limit. Optica 3, 702–706 (2016).

Mulyawan, R. et al. A comparative study of optical concentrators for visible light communications. In Broadband Access Communication Technologies XI, vol. 10128, 142–147 (SPIE, 2017).

Meinardi, F. et al. Certification grade quantum dot luminescent solar concentrator glazing with optical wireless communication capability for connected sustainable architecture. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2304006. https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.202304006 (2024).

van Sark, W. G. et al. Luminescent solar concentrators—A review of recent results. Opt. Express 16, 21773–21792. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.16.021773 (2008).

Umair, M. A. et al. Long-range optical wireless communication system based on a large-area, q-dots fluorescent antenna. Laser Photon. Rev. 17, 2200575. https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.202200575 (2023).

Ndjiongue, A. R., Ngatched, T. M. N., Dobre, O. A. & Haas, H. Toward the use of re-configurable intelligent surfaces in VLC systems: Beam steering. IEEE Wireless Commun. 28, 156–162. https://doi.org/10.1109/MWC.001.2000365 (2021).

Sun, S., Yang, F., Song, J. & Zhang, R. Intelligent reflecting surface for MIMO VLC: Joint design of surface configuration and transceiver signal processing. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 22, 5785–5799. https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2023.3236811 (2023).

Dehghani Soltani, M. et al. High-speed imaging receiver design for 6g optical wireless communications: A rate-FOV trade-off. IEEE Trans. Commun. 71, 1024–1043 (2023).

Chen, C., Zhong, W.-D., Wu, D. & Ghassemlooy, Z. Wide-FOV and high-gain imaging angle diversity receiver for indoor SDM-VLC systems. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 28, 2078–2081. https://doi.org/10.1109/LPT.2016.2584185 (2016).

Chen, T., Liu, L., Tu, B., Zheng, Z. & Hu, W. High-spatial-diversity imaging receiver using fisheye lens for indoor MIMO VLCS. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 26, 2260–2263. https://doi.org/10.1109/LPT.2014.2354458 (2014).

Koonen, T. Indoor optical wireless systems: Technology, trends, and applications. J. Lightwave Technol. 36, 1459–1467. https://doi.org/10.1109/JLT.2017.2787614 (2018).

Portnoi, M. et al. Bandwidth limits of luminescent solar concentrators as detectors in free-space optical communication systems. Light Sci. Appl. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-020-00444-y (2021).

Peyronel, T., Quirk, K. J., Wang, S. C. & Tiecke, T. G. Luminescent detector for free-space optical communication. Optica 3, 787–792. https://doi.org/10.1364/OPTICA.3.000787 (2016).

Ali, W. et al. A gigabit VLC receiver that incorporates a fluorescent antenna and a SIPM. J. Lightwave Technol. 40, 5369–5375. https://doi.org/10.1109/JLT.2021.3095398 (2022).

Mulyawan, R. et al. MIMO visible light communications using a wide field-of-view fluorescent concentrator. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 29, 306–309. https://doi.org/10.1109/LPT.2016.2647717 (2017).

Manousiadis, P. P. et al. Optical antennas for wavelength division multiplexing in visible light communications beyond the étendue limit. Adv. Opt. Mater. 8, 1901139. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.201901139 (2020).

He, C., Lim, Y. & Murata, H. Study of using different colors of fluorescent fibers as optical antennas in white led based-visible light communications. Opt. Express 31, 4015–4028. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.481017 (2023).

Meucci, M. et al. Efficient white-light visible light communication with novel optical antennas based on luminescent solar concentrators. J. Lightwave Technol. 42, 2235–2244 (2024).

Papucci, C. et al. Luminescent solar concentrators with outstanding optical properties by employment of d-a-d quinoxaline fluorophores. J. Mater. Chem. C 9, 15608–15621. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1TC02923A (2021).

Meinardi, F. et al. Highly efficient luminescent solar concentrators based on earth-abundant indirect-bandgap silicon quantum dots. Nat. Photonics 11, 177–185. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2017.5 (2017).

O’Brien, D. et al. Indoor visible light communications: Challenges and prospects. In Free-Space Laser Communications VIII (eds Majumdar, A. K. & Davis, C. C.) , vol. 7091, 709106. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.799503. International Society for Optics and Photonics (SPIE, 2008).

ITU-T. G.975.1: Forward error correction for high bit-rate DWDM submarine systems (2004).

Cossu, G., Khalid, A. M., Choudhury, P., Corsini, R. & Ciaramella, E. 3.4 Gbit/s visible optical wireless transmission based on RGB LED. Opt. Express 20, b501. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.20.00B501 (2012).

Shafik, R. A., Rahman, M. S. & Islam, A. R. On the extended relationships among EVM, BER and SNR as performance metrics. In 2006 International Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering, 408–411. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICECE.2006.355657 (2006).

Hughes-Hartogs, D. Ensemble modem structure for imperfect transmission media (1989).

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by the European Union under the Italian National Recovery and Resilience Plan of NextGenerationEU, partnership on “Telecommunications of the Future” (PE00000001 - program “RESTART”), and in part by the European Union -NextGenerationEU, “Integrated infrastructure initiative in Photonic and Quantum Sciences” - I-PHOQS under Grants IR0000016, ID D2B8D520, and CUP B53C22001750006.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G. C., L. G., L. O., M. M., M. A., J. C., E. C. conceived the experiment. G. C., L. O., M. M., M. A. conducted the experiment. G. C., L. G., L. O., M. M., M. A., J. C., E. C. analyzed the results and wrote the manuscript. M. C., A. P. prepared the luminescent concentrator slab. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cossu, G., Gilli, L., Oliviero, L. et al. Exploiting luminescent solar concentrators in indoor visible light communication systems. Sci Rep 15, 16509 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00932-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00932-4