Abstract

Since infrastructure development has increasingly encountered gneiss, and its complex mechanical characteristics have brought engineering much hardship, research on gneiss has been booming. However, the stress concentration effect in gneiss has seldom been studied. This work found an under-discussed phenomenon and tried to explain it by the stress concentration effect. Specifically, triaxial compression experiments with different confined pressures on gneiss samples with different embedded textures and an improved Cosserat constitutive model were employed to study the textures in gneiss. The constitutive model was meant to simulate the experiment by adjusting the stress concentration effect in the texture areas in gneiss samples. The phenomenon found in the experiment for discussion was that the different textures in gneiss can cause different failure modes but not necessarily affect its compression strength. The phenomenon was then successfully reproduced by the finite element method with the improved Cosserat model by setting different stress concentration degrees in the textures. The experimental and simulation results revealed a potential mechanism to explain the phenomenon: the diverse failure modes observed in gneiss samples with identical strength may result from variations in stress concentration distributions. Lastly, a new method to trigger strain localization by setting stress concentration regions is proposed based on the analysis. This work may provide a different understanding of the failures in rocks with directional textures and inspire studies in localized stress concentration effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gneiss is one of the prevalent rocks in western China1, a region currently experiencing a significant increase in infrastructure development projects, thereby leading to more frequent encounters with this rock type. As infrastructure projects expand, understanding the geotechnical properties of gneiss becomes crucial due to its complex structural characteristics and variable mechanical behavior2,3. Addressing these challenges is vital for ensuring safe and sustainable construction practices.

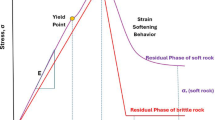

Joints, bedding, etc., have great influences on the mechanical properties of rocks. For gneiss, the beddings are often more noticeable4. Since most gneisses are composed of quartz, biotite, plagioclase, etc5,6, and the natural strength of quartz and biotite is very different, it is plausible to consider that the beddings in gneiss would affect its mechanical strength. Studies that focused on the anisotropy of stratified rocks are not uncommon, and they are inclined to presume the interlayers have different strengths than the rest areas of the rocks7,8,9. However, the weakness of the bedding interlayers might not be prevalent.

Gneiss is formed by deep metamorphism of magmatic rock or sedimentary rocks, and the formation of such a structure will take more than millions of years10. Suppose a rock has been under extremely high confined pressure for millenniums. In that case, its compression strength can be expected to be very high even though part of its composite is the normally weaker mineral biotite. This speculation means rocks with different textures can still have similar compression strength. Therefore, it is doubtful that the textures that appear in gneiss will always affect its compression strength.

Recent studies about gneiss can be divided into two categories: external factors and internal factors on the mechanical properties of gneiss. The research concerning the external factors includes the influence of water immersion on the internal damage of gneiss11, the effect of temperature field (heating12 and freezing13) on the compression strength of gneiss, and the effect of weathering14,15. These works revealed how environmental changes can affect the microstructure of gneiss and consequently affect its mechanical strength. On the other hand, some researchers have studied the influence of schistosity or textures in gneiss3,16,17. They concluded that the rock’s strength and deformation characteristics depend on the alignment of its mineral layers and the loading orientation3,16 and higher stresses may lead to different patterns of strain distribution in gneiss17.

The above research implied that the failure modes of gneiss are complicated and pertain to the microstructure of the rock and its embedded textures. The embedded textures may affect the stress concentration effect in the rock and cause different strain localization patterns. Combining this statement and the abovementioned doubting, it can be speculated that it is possible to observe (maybe occasionally) a phenomenon that the textures in gneiss only affect its failure mode but not its strength. This phenomenon also pertains to the stress concentration effect. However, no previous works have discussed this phenomenon or its connection with the stress concentration effect regarding gneiss. Recent works that studied the stress concentration effect in rocks are noticeably focused on rockburst18 and tunneling19. In other words, studies on the stress concentration effect in gneiss are insufficient.

This work attempts to fill the current research gap in gneiss by employing experiments and theoretical works. The main works herein can be divided into two parts: First, triaxial compression experiments with different confined pressures were carried out on gneiss samples with different embedded textures, in which the abovementioned phenomenon (textures did not necessarily affect the samples’ strength) was observed. Second, the observed experimental phenomenon was reproduced by employing a newly developed constitutive model that can consider the stress concentration effect, and the mechanism of the phenomenon was discussed. Combined with the experiment and the simulation, a possible mechanism was proved that the newfound phenomenon was caused by different stress concentration degrees within and outside the textures during the shearing process.

Experiment details

Materials

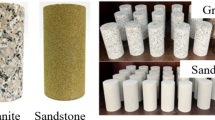

The experiment specimens (gneiss) were cored from the west of China, from extreme cold and highly seismic areas. The specimens were then cut into cylindrical samples with a diameter of 50 mm and a height of 100 mm for the triaxial compression tests. The average weight and density of the samples were 502.5 g and 2.691 g/cm3, respectively. The specific samples before the tests can be seen in Fig. 1.

Apparatus and methods

The triaxial tests were conducted on the MTS815 electro-hydraulic servo rock mechanics test system. The system consists of a loading system, measuring system, and control system, which can accurately monitor the mechanical changes of the specimens under conventional triaxial loading conditions. The test apparatus is exhibited in Fig. 1. The triaxial tests were arranged with 3 kinds of confined pressures, i.e., 5 MPa, 15 MPa, and 25 MPa. The whole process during the tests can be sketched as follows: First, the confining pressure was applied on every sample at a low rate of 0.75 MPa/s; when the confining pressure reached the objective value, the axial loading would be applied to the samples with a rate of 0.001 m/s while the confining pressure would be held unchanged. Once the rock sample is damaged and the corresponding post-peak curve has been obtained, the test will be terminated. After the tests, photos of the test samples were taken while maintaining the heat shrink film on the samples intact so that the crack could be clearly observed.

Experiment results and analysis

Experiment results

The experiment results are presented in Figs. 2 and 3; while Fig. 2 records the failure mode of every sample, Fig. 3 exhibits the equivalent stress and hoop strain εh curves along with the axial strain εa of every sample. The confining pressure 5 MPa, 15 MPa, and 25 MPa are termed as CP5, CP15, and CP25. The darker sample in Fig. 2b was tainted by the motor oil during the experiment, but its mechanical strength was not affected.

Clear as in Fig. 2, the gneiss samples all have many oriented black and white textures. Though the samples shown in Fig. 2a to c shared similar transverse textures, the cracks within them did not precisely follow the transverse textures. Instead, they all seemingly have cracks that initially follow the textures but eventually extend to the bottom of the sample. The sample in Fig. 1d is different; embedded with vertical textures, the three most apparent cracks in the sample all follow the textures. This sample was set as a reference to the samples with transverse textures.

Unlike Figs. 2 and 3 tells the difference between the samples regarding the stress and strain changes. As expected, in Fig. 3a, samples with higher confining pressures have higher strength; the peak equivalent stress of the samples with transverse textures under CP5, CP15, and CP25 were respectively 210 MPa, 245 MPa, and 305 MPa. Besides, their equivalent stress curves and hoop strain curves are pretty similar. They share the same changing trends and have identical slopes on their approximately linear sections, which means the parallel samples have very close deformation modulus E and Poisson’s ratio v. Surprise is bid on the sample with vertical textures. Though the failure modes of samples with different textures varied apparently, the peak strengths of the two samples under 15 MPa confining pressure exhibited in Fig. 3a are nearly the same. Moreover, the stress and hoop strain curves of the samples with transverse and vertical textures are nearly identical, except for the differences observed on the rear failure sections.

The stress concentration effect in the experiment

The experiment results of the samples with transverse and vertical textures disclosed in Figs. 2 and 3 demonstrate that textures may not necessarily affect the samples’ shear strength. Though the failure modes of samples with different textures are different, their stress and strain curve changes can still be very similar. That leads to a problem about the influence of the textures: How do the textures affect the samples’ mechanical properties? Herein, a speculation is proposed and will be discussed in the later part of this work.

The white part of the gneiss samples is mainly quartz, while the black part is mostly biotite5,6. The compressive strength of quartz is usually higher than that of biotite, but the diagenetic environment may have fused them into new crystal structures20 that may have similar compression strength as quartz. However, the composition of biotite is more complicated, comprising SiO2, MgO, Al2O3, K2O, etc21, while quartz is composed chiefly of SiO2. After the diagenesis, the white part, composed of simple crystal structures (SiO2), will have better integrity and be closer to a continuum. In contrast, the black part, composed of more complex crystal structures, will be more similar to a discrete medium. The uneven stress concentration phenomenon tends to occur in discrete media, such as the stress arching effect in sand piles22,23. Therefore, it seems plausible to assume that the textures in some stone samples will only affect the stress concentration effect in the samples, i.e., black areas are more prone to stress concentration than white areas. And this concentration effect will lead to different failure modes other than different shear strengths. This work aims to demonstrate the rationality of this concept.

Theoretical approaches

Herein, a newly developed constitutive model (named multiscale Cosserat model, i.e., MC model)24 based on the conventional Cosserat model is employed to consider the stress concentration phenomenon. A brief introduction to the Cosserat models is given below:

Conventional Cosserat model

Governing equation and elasticity

The conventional Cosserat continuum theory25 deploys six freedom degrees (3D conditions) for each calculation point.

Herein, ui and ωi are, respectively, the displacement vector and rotation vector, each with three directional components. Correspondingly, the strain tensor \({\varepsilon _{ij}}\) and the micro-curvature tensor \({\kappa _{ij}}\) should each contain nine components, as shown in Eq. (2).

Xi here represents the coordinate vector.

Accordingly, referring to the elastic matrix given in the work of de Borst25, the incremental form elastic constitutive can be expressed by a tensor formula, as in Eq. (3).

Herein, \(\sigma _{{ij}}^{{}}\) and \(m_{{ij}}^{{}}\) are the stress tensor and the couple stress tensor; G and α, the shear modulus and lame constant in classical elastic models26; E and µ, the elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio; Gc, a rotation modulus associated with the independent rotation of the element; l has the same definition as in Cosserat theory. Amidst, the obtaining of Gc would need a specially designed torsion test, which has not yet gained universal agreement in research. Therefore, to discuss the mesh dependency, the Gc will be taken as the same as G in this paper as a simplification (i.e., G = Gc).

Elastoplasticity

According to the traditional elastoplastic theory, when the stress of an element is over or on the initial yield surface, the element will turn into the elastoplastic condition; for a Cosserat continuum, the expression of the yield surface will be slightly different. The Drucker-Prager (D-P) yield function27 is employed here for demonstration, as in Eq. (5).

Herein, \(B=\frac{{{\text{2}}\sin \varphi }}{{3 - \sin \varphi }}\) and \(C=\frac{{6\cos \varphi }}{{3 - \sin \varphi }}\); when the plane strain condition applies, they turn to \(B=\frac{{{\text{2}}\sqrt 3 \sin \varphi }}{{3(3 - \sin \varphi )}}\) and \(C=\frac{{2\sqrt 3 \cos \varphi }}{{3 - \sin \varphi }}\)28; the mean stress P and the equivalent stress \(\bar {\sigma }\) are the main difference from the classic elastoplastic theory; here, J2, \({S_{ij}}\) and \(m_{{ij}}^{{\text{s}}}\) are respectively the second invariant of the deviatoric stresses, the deviatoric stress tensor, and the deviatoric couple-stress tensor; c and φ, the cohesion and the internal friction angle; a1, a2, and a3 are material related parameters (a1 = 0.25, a2 = 0, and a3 = 0.25 was adopted in this paper to make its form consistent with the traditional equivalent stress tensor and equalize the contribution of the deviatoric stress tensor and the couple stress tensor). Amidst, c was set as the yield stress and made a function of the equivalent plastic strain \({\bar {\gamma }_p}\), as in Eq. (9).

The equivalent strain \(\bar {\gamma }\), the deviatoric strain tensor \({e_{ij}}\), and the deviatoric couple-strain tensor \(\kappa _{{ij}}^{{\text{s}}}\) (plastic or not) all took the forms corresponding to the stress tensors showed in Eq. (5); material parameters a affects the curve slope at the initial yield surface during the hardening/softening, and c0 is the initial yield cohesion.

When the associated flow rule is applied, referring to derivation presented by de Borst25, the incremental form constitutive of Cosserat elastoplastic continua can be obtained, as in Eq. (12). The numerical implementation of the Cosserat method can refer to the work of Panteghini & Lagioia29.

Amidst, \({F_{ij}}=\frac{{\partial f}}{{\partial {\sigma _{ij}}}}=\frac{3}{{2\bar {\sigma }}}{S_{ij}}+B{\delta _{ij}}\); \({F^{\prime}_{ij}}=\frac{{\partial f}}{{\partial {m_{ij}}}}=\frac{3}{{2\bar {\sigma }}}{l^{ - 2}}m_{{ij}}^{{\text{s}}}+B{l^{ - 1}}{\delta _{ij}}\); \({T_{ij}}=\frac{{2G{F_{ij}}+3\alpha B{\delta _{ij}}}}{{H+\chi }}\); \({T^{\prime}_{ij}}=\frac{{2G{l^2}{{F^{\prime}}_{ij}}}}{{H+\chi }}\); \(\chi =3[G+{B^2}(4G+3\alpha )]\); \(H=C\frac{{\partial c({{\bar {\gamma }}_p})}}{{\partial {{\bar {\gamma }}_p}}}=Ca\).

Multiscale Cosserat model

Governing equation

The conventional Cosserat theory or the classic elastoplastic theory would consider that the displacement in an analytical element (Fig. 4) is all equal, i.e., an analytical element is a mathematic point with no geometric dimensions. In contrast, in the multiscale Cosserat continua, the displacement within an analytical element is considered distributed, and the analytical element is relatively tiny but not without geometric dimensions.

In this way, the displacement of a random material point on an analytical element can be expressed by Eq. (13):

As shown in Fig. 5, \({u_0}=\delta {X_0}\) is the displacement vector from the local coordinate origin to the global coordinate origin; \(\delta (\Delta X^{\prime})=u^{\prime}+{\theta _{\text{D}}} \times \Delta X^{\prime}\) is the displacement of the material point in the local coordinate system, where \(u^{\prime}\) is the displacement caused by the macroscopic strain of the element, and \({\theta _{\text{D}}} \times \Delta X^{\prime}\) is the displacement caused by the independent rotation of the element; \(\Delta X^{\prime}=i\Delta x^{\prime}+j\Delta y^{\prime}+k\Delta z^{\prime}\)is the local coordinate increment vector, indicating the position of the original point D relative to the local coordinate origin \(o^{\prime}\). It should be noted that the local coordinate system only includes the displacement caused by the deformation and rotation of the system. Setting up a local coordinate system is to facilitate considering the uneven strain/stress distribution in the analytical unit. The displacement of the material point in the global coordinate can be further expressed as:

Where \(\varepsilon ^{\prime}\) represents the displacement gradient tensor.

Accordingly, the directional displacement component of any point related to the local system can be expressed as:

Where \({\varepsilon _{ij}}={u^{\prime}}_{{i,j}} - {e_{ijk}}{\omega _k}\) is the displacement gradient tensor of a material point. Similarly, the rotation component of any point related to the local system can be expressed by Eq. (16).

Perform Taylor expansion on Eq. (15) and Eq. (16) at \({X^{\prime}_0}=0\) while ignoring any second-order partial differential terms to represent the incremental displacement and rotation vectors of the entire analytical element; then Eq. (15) and Eq. (16) can be transformed into Eq. (17).

Referring to the governing equation of the conventional Cosserat theory, the strain tensor and the micro-curvature tensor in the local coordinate system can then be derived according to the gradient of the incremental displacement and rotation vectors with respect to the local coordinate vector.

While the second derivative can be expressed as:

In this paper, the local coordinate system does not involve rotation, so when \({X^{\prime}_0}=0\), the strain tensor, the micro-curvature tensor, and their second derivatives in either the local coordinate system or the global one are consistent.

Stress expression of the analysis element

The classic elastoplastic (CEP) model evenly considers that the stress tensor on the analysis element shares the same value. In contrast, within a multiscale Cosserat continuum, the stress tensor has been considered to be distributed variously throughout the analysis element, which also pertains to the distance from the calculated point to the element center (the origin of the local coordinate system), as shown in Fig. 6. Therefore, the stress of the entire analysis element can be expressed by the Taylor formula at the origin of the local coordinate system.

Where \({\text{d}}\sigma^{\prime}_{{ij}}(0)\), \({\text{d}}m^{\prime}_{{ij}}(0)\), \(\frac{{\partial ({\text{d}}\sigma ^{\prime}_{{ij}}(0))}}{{\partial x_{q}}}D_{q}\), and \(\frac{{\partial ({\text{d}}m^{\prime}_{{ij}}(0))}}{{\partial x_{q}}}D_{q}\) can be expressed by Eq. (21) to Eq. (23):

Herein, \(\frac{{\partial {T_{ni}}}}{{\partial {{\varepsilon ^{\prime}}}_{{op}}}}={T_{ni}}{Q_{op}}\), \(\frac{{\partial {{T^{\prime}}_{ni}}}}{{\partial {{\varepsilon ^{\prime}}}_{{op}}}}={T^{\prime}_{ni}}{Q_{op}}\), and \({Q_{ij}}=\frac{{\partial \frac{1}{{H+\chi }}}}{{\partial {{\varepsilon ^{\prime}}^{}}_{{ij}}}}(H+\chi )=\frac{{2abC}}{{(H+\chi ){{(a+b{{\bar {\varepsilon }^{\prime}}_p})}^3}}} \cdot \frac{{{S^{\prime}_{ij}}}}{{\bar {\sigma }^{\prime}}}\). Equation (21) indicates that the first term of Taylor’s expansion is no different from the conventional Cosserat theory (as in Eq. (12)) when it takes the local coordinate origin’s value, i.e., \(D_{q}\) takes a value as 0; this has functioned the model with the possibility to regress to the conventional Cosserat form. The \(D_{q}\) is a vector with three variables; if the expression of anisotropy is not necessary, the values in the three directions can be set the same. Related only to the deformation and rotation of the particle system, Dq is physically a length scale that pertains to factors such as particle size and contact position. In this work, the continuum media containing both scale factors (l and Dq) are deemed the multiscale Cosserat continua. Referring to the linear approximation methods30, the stress at a specific position of the unit can be chosen to represent the stress of the whole unit, which means the Dq will have a relationship with the element size (the n in Fig. 6); more actual cases and effort are expected to study its physical meaning.

Description of the stress concentration phenomenon

The stress concentration problem of a circular hole in a plate is classic in elastic mechanics; for instance, a plate with a round hole at the center is under a pair of unidirectional load p (as in Fig. 7). According to elastic mechanics31, when the hole radius is much less than the size of the plate, the loop stress \({\sigma _\theta }\) around the hole can be expressed as Eq. (24). Equation (24) denotes that the maximum value of the loop stress \({\sigma _\theta }\) will appear at when \(\theta = \pm 90^\circ\) and the max value will be 3p. The multiple of p here is usually deemed a stress concentration factor k. Herein, a computation model composed of elements with a minimum size of 2 mm was adopted to evaluate the stress concentration effect of the proposed constitutive model (multiscale Cosserat model). Within the computation model, the hole radius was chosen as 0.01 m, while the plate size was selected as 1 m. For this elastic simulation, when focused only on the change of the stress concentration factor k, the material parameters, such as the elastic modulus E and the Poisson’s ratio v, are less important, for they will not affect the stress concentration effect31. Nonetheless, the material parameters adopted for the computation models are disclosed in Table 1. According to the derivation of the multiscale Cosserat model, the physical meaning of Dq, when its value is larger than the element size, will be hard to understand. Therefore, the internal length scales of the two Cosserat models were chosen to be less than 0.002 m.

The computation results of the CEP, conventional Cosserat, and multiscale Cosserat constitutive models are presented in Fig. 8. Figure 8a is a showcase of the stress distribution results, in which the maximum stress value appeared at when \(\theta = \pm 90^\circ\). It can be seen from Fig. 8b that the stress concentration factor k of the CEP model is quite close to the theoretical solution demonstrated by Eq. (24), i.e., k = 3. Simultaneously, the k results of the two Cosserat models stem and bifurcate from this value. This result indicates that the two Cosserat models have a good homology with the CEP model. However, the two Cosserat models have different influences on the stress concentration effect; the growth of length scale Dq of the multiscale Cosserat model will enhance the concentration effect and enlarge the factor k, while the growth of the length scale l will do the opposite. Moreover, the influence of the length scale Dq seems more intense than that of the length scale l, observing the slope changes of the two curves. A possible explanation is given here to explain the enhanced stress concentration effect caused by larger Dq:

Physically, larger Dq can represent the larger particle size of the particles in the material. The larger the particle size, the smaller the specific surface area, so the contact between the particles will be reduced. With fewer contact points, the stress conveying between the particles will also be larger; the stress concentration effect will obviously be enhanced.

In summary, this section demonstrated that the length scale of the multiscale Cosserat model will intensify the stress concentration phenomenon in the computation model; in contrast, the length scale of the conventional Cosserat model will relieve it.

Simulation and analysis of failure modes of gneiss with different stress concentration areas

Plain strain triaxial compression simulation

In this section, plain strain triaxial compression simulations were adopted to simulate the abovementioned stress concentration effect found in the experiment.

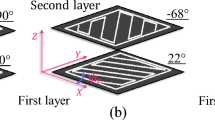

Modelling details

Herein, the triaxial experiments with a confining pressure of 15 MPa were taken as a reference for the plain strain triaxial compression simulations, including the boundary conditions and dimensions of the simulation models. As depicted in Fig. 9, the simulation models were built roughly referred to the transverse and vertical textures embedded in the experiment samples and meshed by user-defined 8-node biquadratic plane strain quadrilateral elements. The textures were represented by a few strips with widths of 2 mm. The two models with different textures were meshed completely the same to avoid mesh dependence problems. The loading processes involved two steps: the confining pressure loading and the axial loading. In the first step, 15 MPa cell pressure was applied to each free surface of the calculation model and remained for the next step. In the second step, the vertical displacement and rotation on top of the numerical model were restricted, and a vertical displacement was applied to the bottom of the model with the horizontal displacement and rotation of the bottom surface fixed (in this example, the final displacement was set as 3 mm). All the computations of this work were implemented in Abaqus; with user-defined elements (UEL), the multiscale Cosserat constitutive model introduced in this work was used for the simulation; the calibration of the constitutive parameters will be discussed in the next section.

Parameters calibration

In previous attempts, we discovered that when the internal friction angle φ is greater than around 20°, shear bands would be hard to forge in the model under the abovementioned boundary conditions. This defect may be caused by excessive plastic dilation when using the associated flow rule, idealized boundary setup, non-consideration of the rock damage characteristics, etc. On the other hand, when φ is set as 0, the D-P function will regress to the Mises yield function. With the Mises yield function and the associated flow rule, clear shear bands can easily be observed in the simulation. However, the Mises yield function is more suitable to describe metallic materials rather than geotechnical materials. Therefore, the D-P and Mises yield functions were both employed in this simulation to reflect the stress concentration phenomenon observed in the experiment. The stress-strain curve of the triaxial experiment results with a confining pressure of 15 MPa, as in Fig. 3a, was chosen as the calibration reference; since the main objective was to simulate the different failure modes caused by the stress concentration effect, not the nonlinearity of the entire curve, the reference curve was simplified to a straight line for calibration (as exhibited in Fig. 10). According to Eq. (3), the elastic modulus and the Poisson’s ratio can be obtained by the Eq. (25) using the linear section of the stress-strain curve of the experiment. The Mohr’s circles (as in Fig. 11) were also drawn to obtain the c and φ values serving as benchmarks. The E, c0, and φ for the Cosserat model with D-P yield function (Cosserat-D-P) were modified higher than the benchmarks due to the incompatibility of the constitutive model (plane strain condition) and the experiment. The parameters after calibration and the stress-strain curves for comparison abstracted from the model are presented in Table 2 and Fig. 10.

Where σa, σc, εa, and εh are, respectively, the axial stress, cell pressure, axial strain, and loop strain.

It can be seen that the calibration was well performed on the model with the Mises yield function, yet a clear deviation still looms in the calibration where the D-P yield function was used. This difference was mainly because the plasticity develops in the models differently; since the D-P yield function pertains to the normal stresses of the elements, the stress redistribution in the models will be more complex. Hence, the model’s axial stress and strain curve that used the D-P yield function would yield gradually until the curve reaches the drastically dropping part and the computation diverges, i.e., the elements in the model would gradually enter the plastic condition. Herein, the flow rule and the plane strain conditions may vary from the experiment, so forcing the calibration results to be completely the same as the experiment would be meaningless. Given this, the calibration based on the D-P yield function was only performed to simulate the peak strength of the reference curve for later discussion on the stress concentration effect.

Moreover, since the multiscale Cosserat (MultisCos) model stems from the conventional Cosserat (Cos) model with one extra internal length scale Dq, the calibration was conducted only based on the conventional Cosserat model. By adding the setup with different Dq and changes with the conventional length scale l, the computation model will face different stress concentration effects, which will be discussed in the following sections.

Simulation result comparisons

The simulation results of the computation models with Mises and D-P yield function when the computation diverged are presented in Figs. 12 and 13. Figures 12 and 13 each contain three equivalent strain contour maps and one stress-strain graphs demonstrating the failure mode difference and the strength changes caused by the stress concentration effect. Figures 12a and b and 13a and b, and Figs. 12c and 13c, respectively, show the strain distribution within the models with no textures, transverse textures, and vertical textures. The axial stress in Figs. 12d and 13d refers to the average stress calculated from the nodal reaction forces on the model’s bottom surface. The parameters set for the constitutive model to adjust the stress concentration effect are exhibited in Figs. 12d and 13d.

It is evident that shear bands have occurred in the model that adopted the Mises yield function, which means the model has ended up with overall shear failures. As depicted in Fig. 8b, a larger length scale Dq represents an enhanced stress concentration effect, and a larger length scale l means to weaken stress concentration. Therefore, as in the tables of Figs. 12d and 13d, when the length scale l and Dq were set to highlight the stress concentration effect within the textures, the shear bands will reshape according to the adjusted stress distribution. It can be seen from Fig. 12b that the shear bands within the model with transverse textures have migrated to the upper part of the model, with some serrations on the edge of the band; the shear band in Fig. 12c has even been flipped left-to-right compare to Fig. 12a. However, the zoomed-in stress curves in Fig. 12b denote that the axial compressive strengths of the three models were nearly unchanged. This result is consistent with what we found in the experiment, i.e., the two samples with different textures have very close compressive strength and much different failure modes. Nevertheless, this evidence alone is insufficient to support this phenomenon’s rationality because the Mises yield function is free from the influence of normal stresses and frictional effects; evidence based on the D-P yield function is needed to make it more plausible.

As mentioned above, since the φ is over 20°, the equivalent strain map did not exhibit apparent shear bands. The strain concentration areas near the left bottom of the model (Fig. 13b and c) denote that the computation was ended due to local failures. Without clear shear bands, the stress concentration effect mostly displayed subtle differences, for instance, the serration edges in the equivalent strain maps corresponding to the textures’ directions. However, the equivalent strain distributions are quite different near the left bottom of the model, where the localized strain concentration occurs. This phenomenon means the stress concentration effect mainly affects the stress localization areas. On the other hand, unlike the Mises yield function model groups, the stress peaks in Fig. 13d have shown some differences. Still, the compressive strength difference between the three models was less than 1% (244 ~ 246 MPa), a deviation consistent with the experiment (Fig. 3). This result can also be marked as evidence for the rationality of the stress concentration effect that was found in the experiment.

In summary, the simulations theoretically proved that it is possible for the textures in stone samples to only affect the sample’s failure mode instead of its compressive strength, and this phenomenon can be simulated or explained by the different stress concentration degrees inside and outside of the textures.

Influence of the width and comparison with the initial defect

Modelling details

In the last section, the D-P yield function simulation models did not exhibit a clear shear band. However, the D-P model is more suitable for simulating geotechnical materials. Hence, in this section, the D-P yield function is employed to explore the influence of the width of concentration areas on the stress concentration effect while the internal friction angle φ is reduced to 24°. Meanwhile, another simulation model with weakened elements was set for comparison to disclose the difference between localization phenomena caused by initial defects and concentration areas; the initial yielding cohesion c0 in the weakened areas was reduced by 10% to trigger a different localization phenomenon. The detailed parameters used for different areas in the models are exhibited in Table 3; the different values used are highlighted in bold. The concentration areas with varied widths set in the model can be observed in Fig. 14, while the weakened area in the model for comparison takes after the concentration area when the width is 16 mm. As in Fig. 14, the boundary conditions for the loading process are nearly the same as the second step in the simulation model of the last section, except the cell pressure is not considered in this discussion.

Discussion on the width of the concentration areas

The simulation results showing the influence of the width of the concentration areas are displayed in Figs. 15 and 16, and Fig. 17, which present the equivalent strain contour maps, the rotation displacement contour maps, and the axial stress-strain curves of the model.

First, it can be seen from the equivalent strain contour maps in Fig. 15 that, without any concentration area, the computation result will present two crossing shear bands. Still, when the concentration areas are activated, the strain localization area will change to unidirectional. Second, as the width of the concentration areas grew from 4 mm to 32 mm, the localization area on the top-left of the model also grew. However, the overall strain localization distributions of the models with concentration areas are almost identical. Last but not least, it can be judged that the computation diverges earlier as the concentration areas enlarge since the final step time is successively decreasing.

Figure 16, on the contrary, demonstrates apparent influences of the width on the rotation displacement. Not only was the rotation displacement in the concentration areas growing along with the growing width, but the other parts in the model were also shrinking or sharpening. However, compared with the localization in the model without concentration areas, it appears that the influence of the rotation displacement is wide but less significant. It can also be confirmed from Fig. 17 that the width of concentration areas has little effect on the models’ compression strength, as the curves almost extend from the same path and have nearly the same peak value.

The above descriptions mean that the influence of the concentration areas is prompt; the existence of the concentration areas will greatly affect the strain localization, while the width of the concentration areas only has a limited influence on the overall strain distribution and the compression strength of the model. The rotation displacement results can also help to deduce that the stress concentration effect in the concentration areas was mainly exerted by the changes in the rotation displacement.

Comparison with the initial defect

The simulation model with weakened elements was set for comparison to discuss the different influences of initial defects and concentration areas. The comparison results can be observed in Figs. 17 and 18.

The first noticeable difference is the peak stress of the two models; while the stress-strain curve of the width-16 mm model basically overlaps with that of the model without a concentration area, the stress-strain curve of the model with a 16 mm width weaken area has a clear lower peak stress value.

The second difference is that the equivalent strain contour map of the weakened model contains a clear shear band, but the model with concentration areas only has corresponding strain localization areas (Fig. 18). Moreover, it can be seen that the rotation displacement of the model with the weakened area almost do not have a localization effect within the defect area. On the contrary, a clear localization effect can be observed within the concentration area of the other model. This result implies that, unlike the model with concentration areas, the strain localization of the weakened model did not stem from the changes in the rotation displacement. Then, it will be rational to understand why the concentration areas did not trigger clear shear bands, for it is natural that the rotation displacement is transferring between elements from area to area, and the transfer of rotation tends to result in smooth and rounded borders. Besides, compared with the translational displacements, the rotation is a higher-order variation that has a larger influence range among the adjacent elements. Therefore, unlike the shear band caused by the initial defects, the strain localization areas caused by the concentration areas are wider.

The above discussion denotes that the setting of concentration areas can be recognized as a new method to trigger the localization within a computation model, while the localization mainly stems from the redistribution of the rotation displacement, and it will not affect the strength of the model. This new method to study the different failure modes may help in some engineering scenarios, such as the prediction of different critical deformation areas in slopes.

Conclusion

In this work, triaxial experiments and the finite element method (FEM) were employed to study the stress concentration effect in gneiss. While the experiment mainly considers the influence of the embedded textures in gneiss on its compression strength, the FEM, together with an improved Cosserat model, was applied to analyze the mechanism of the phenomenon found in the experiment. The main findings of this study can be concluded as follows:

-

1.

An under-discussed phenomenon was found in the experiments that different textures on gneiss samples with similar mechanical strength may result in various failure modes, i.e., the schistosity of gneiss will affect its failure modes but not necessarily the strength.

-

2.

It was proved that by implanting different stress concentration patterns, it is possible to alter the failure modes of simulated samples without affecting their strength, suggesting that the under-discussed phenomenon may be caused by the different stress concentration degrees within and outside the textures during the shearing process.

-

3.

Based on the analysis, it was found that the multiscale Cosserat model used to simulate the experiment mainly enhances the stress concentration effect via the rotation displacement, which is quite different from the mechanical strength parameter-driven strain localization phenomenon.

The phenomenon and the method used to study the phenomenon may shed some light for researchers who work on similar topics, and the newfound method that used the stress concentration effect to trigger strain localization may come in handy in studying the strength differences and different failure modes due to non-local weakening.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

References

Liu, S., Lan, H. & Martin, C. D. Effect of disturbance on the progressive failure process of Eastern Himalayan gneiss. Eng. Geol. 312, (2023).

Liu, L., Xu, W. Y., Zhao, L. Y., Zhu, Q. Z. & Wang, R. B. An experimental and numerical investigation of the mechanical behavior of granite gneiss under compression. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 50, 499–506 (2017).

Liu, X., Feng, X. & Zhou, Y. Experimental study of mechanical behavior of gneiss considering the orientation of schistosity under true triaxial compression. Int. J. Geomech. 20, (2020).

Majumder, D. B. & Samanta, S. K. Development of flanking structures in layered gneissic Rock: insights from numerical modelling. J. Struct. Geol. 174, (2023).

Holyoke, C. W. & Tullis, J. The interaction between reaction and deformation: an experimental study using a biotite plus plagioclase plus quartz gneiss. J. Metamorph Geol. 24, 743–762 (2006).

Yuquan, W. et al. Incipient charnockite formation in the Trivandrum block, southern India; evidence from melt-related reaction textures and phase equilibria modelling. Lithos. 380–381, 105825 (2021).

Duan, K., Li, Y., Wang, L., Zhao, G. & Wu, W. Dynamic responses and failure modes of stratified sedimentary rocks. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 122, (2019).

Shang, J., Duan, K., Gui, Y., Handley, K. & Zhao, Z. Numerical investigation of the direct tensile behaviour of laminated and transversely isotropic rocks containing incipient bedding Planes with different strengths. Comput. Geotech. 104, 373–388 (2018).

Tang, H., Wei, W., Song, X. & Liu, F. An anisotropic elastoplastic Cosserat continuum model for shear failure in stratified geomaterials. Eng. Geol. 293, (2021).

Li, X. et al. Anatexis of former arc magmatic rocks during oceanic subduction: A case study from the North Wulan gneiss complex. Gondwana Res. 61, 128–149 (2018).

Sun, C., Xie, B., Wang, R., Deng, X. & Wu, J. Investigation of internal damage evolution in gneiss considering water softening. Sci. Rep. 13, 12672 (2023).

Costa, K. O. B. et al. Influence of high temperatures on physical properties and microstructure of gneiss. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 80, 7069–7081 (2021).

Wang, L., Liu, Z., Han, J., Zhang, J. & Liu, W. Mechanical properties and strain localization characteristics of gneiss under Freeze–Thaw cycles. Eng. Fract. Mech. 298, (2024).

Biondino, D. et al. A multidisciplinary approach to investigate weathering processes affecting gneissic rocks (Calabria, Southern Italy). Catena (Giessen). 187, 104372 (2020).

Monticelli, J. P., Ribeiro, R. & Futai, M. Relationship between durability index and uniaxial compressive strength of a gneissic rock at different weathering grades. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 79, 1381–1397 (2020).

Liu, X., Feng, X. & Zhou, Y. Influences of schistosity structure and differential stress on failure and strength behaviors of an anisotropic foliated rock under true triaxial compression. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 56, 1273–1287 (2023).

Wang, R., Wang, Y., Deng, X., Qin, Y. & Xie, B. Investigation on the properties of gneiss under different ground stresses. Sens. (Basel Switzerland). 22, 1591 (2022).

Zhao, G., Wang, D., Gao, B. & Wang, S. Modifying rock burst criteria based on observations in a division tunnel. Eng. Geol. 216, 153–160 (2017).

Shi, L. & Zhang, X. An experimental investigation on the failure behaviour of surrounding rock in the stress concentration area of deeply buried tunnels. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 82, (2023).

Grocolas, T. & Müntener, O. The role of Peritectic biotite for the chemical and mechanical differentiation of felsic plutonic rocks (Western Adamello, Italy). J. Petrol. 65, (2024).

Zeng, Q., Sun, W., Zhong, H. & He, Z. Efficient removal of Cd(2+) from aqueous solution with a novel composite of silicon supported nano iron/aluminum/magnesium (Hydr)Oxides prepared from biotite. J. Environ. Manage. 305, 114288 (2022).

Fang, Y., Li, X., Guo, L., Gu, R. & Luo, W. The experiment and analysis of the repose angle and the stress Arch-Caused stress dip of the sandpile. Granul. Matter 24, (2022).

Vanel, L., Howell, D., Clark, D., Behringer, R. P. & Clement, E. Memories in sand: experimental tests of construction history on stress distributions under sandpiles. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Phys. Plasmas Fluids Relat. Interdiscip Top. 60, R5040–R5043 (1999).

Guo, L. et al. A new multiscale Cosserat model for size effect simulation in granular media. Comput. Geotech. 170, (2024).

de Borst, R. Simulation of strain localization: A reappraisal of the Cosserat continuum. Eng. Comput. 4, 317–332 (1991).

Anandarajah, A. Computational Methods in Elasticity and Plasticity:Solids and Porous Media (Springer, 2010).

Drucker, D. C. Soil mechanics and plastic analysis or limit design. Q. Appl. Math. 2, 157–165 (1952).

de Borst, R., Sabet, S. A. & Hageman, T. Non-Associated Cosserat plasticity. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 230, 107535 (2022).

Panteghini, A. & Lagioia, R. An implicit integration algorithm based on invariants for isotropic elasto-plastic models of the Cosserat continuum. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 46, 2233–2267 (2022).

Areias, P., Rabczuk, T. & Ambrósio, J. H. E. R. K. Integration of finite-strain fully anisotropic plasticity models. Finite Elem. Anal. Des. 185, 103492 (2021).

Chong, K. P., Lee, J. D. & Boresi, A. P. Elasticity in Engineering Mechanics 3rd edn (Wiley, 2011).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to deeply appreciate the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12302502, No. 52109125, and No. 52308354) and Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Grant No. 2022A1515110804 and No. 2023A1515012630), the independent research project of the State Key Laboratory of Subtropical Building and Urban Science (No. 2023ZB15), and Key Laboratory of Geomechanics and Geotechnical Engineering Safety, Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. SKLGME023001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.F. Guo wrote the main manuscript and D.Q. Song prepared experiments . All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, L., Zhang, B., Huang, K. et al. Failure modes affected by stress concentration in gneiss: laboratory triaxial experiment and numerical reproduction. Sci Rep 15, 16234 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00949-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00949-9