Abstract

Particulate air pollution is associated with excess deaths and increases in hospital admissions because of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. Several scientific studies and assessments have linked particulate pollution to a variety of health problems. In this paper, we provide a single cell in vitro analysis for the effect of the particles, which can enter into blood stream, on red blood cells (RBCs). The RBCs under experiment are incubated with \(\mathrm {Fe_3O_4}\) particle as the most abundant air pollutants in big cities. The self-referencing digital holographic microscopy (DHM) in Gates’ arrangement as a vibration-immune methodology is considered here for live visualization and quantitative analysis of the cells. DHM is a label-free and noninvasive method, therefore, suitable for quantitative and morphometric imaging of biological specimens in arbitrary time scales and at video rates. Single RBCs are immobilized by a blinking multiple optical trapping system integrated to the DHM system. Through post-process numerical reconstruction of the recorded digital holograms, the morphology changes of the pollution-exposed RBCs are tracked and expressed in terms of volume and several statistical morphometry parameters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Particulate air pollution may be caused as a result of industrial activities, transportations, intense bushfires, unusual desertification through climate changes and human activity influence, and plowing in semiarid environment1. Air pollution, currently, is the most effective environmental problem and comes along with several long-lasted issues in health, agriculture, industry, and economy, especially in big cities and industrial zones2,3. It is proved by comparative and statistical studies along with clinical evidences that long-term exposure to particulate air pollution, even at low levels, correlates with cardiac and respiratory illness and cancers4,5. According to the cause of the pollutions, their danger level can be categorized. Particles generated by combustion engine are much more harmful to human than the ones from desertification6,7. More importantly, their sizes usually are small, and their presence in blood stream can cause serious health problems2,8,9. The pollutants below 2.5 \(\mu\)m (PM2.5) can enter the human respiratory system and, through it, the blood stream10,11. In a recent study, according to the Ministry of Health and Medical Education of Iran, in the period of April, 2020 to April, 2021, over 11000 deaths related to PM2.5 pollutant, e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung cancer, stroke, and ischemic heart disease, are reported in Iran12. Based on the various studies, official organizations have defined standards for the allowed level of pollutants. For example, for PM10 and PM2.5 the allowed levels are 154 \(\frac{\mu {\textrm{g}}}{\mathrm{{m}^3}}\) and 35 \(\frac{\mu {\textrm{g}}}{\mathrm{{m}^3}}\), respectively13.

In this paper, according to the importance of PM2.5 effects and their possibility to enter the blood stream, we consider their effects on single red blood cells (RBCs). RBCs in cellular portion of mammal blood carry oxygen, therefore they are in intimate contact with many areas of the body. Exposure of such areas to the environment creates several entryways for external harmful elements to enter the blood. Some blood disorders, in fact, are known to be resulted from the presence of toxic materials in the environment14,15. Air pollution is the source of a wide variety of materials, such as benzene, lead and other heavy metals, carbon monoxide, volatile nitrites, and pesticides and herbicides, that may enter the blood. Therefore, due to the harmful effects of these materials and the constant circulation of blood, the hematopoietic system is vulnerable to poisoning. The particles entered the blood stream can adhere to the surface or even enter the cells16,17. It is reported that iron oxide nanoparticles (NPs) can increase the membrane permeability of human microvascular endothelial cells18. In our study, we examine the effect of \(\mathrm {Fe_3O_4}\) PM2.5 particles on the RBCs, as these particles are the dominant constituent of airborne pollution in big cities19,20. Vehicles are the major source of Fe-bearing particles in the environment. These particles are found in exhaust emissions, which may be originated from several sources. One of the main sources is the fuel additives, e.g., ferrocene that contain Fe impurities21. Also the aging of steel in the engine or melting of engine fragments in the combustion chamber and subsequent crystallization during cooling are other major environmental sources for \(\mathrm {Fe_3O_4}\) particles22,23.

RBCs have been subjected to numerous investigations by incorporating various chemical, optical, mechanical, biochemical, or electrochemical techniques, which are performed in vitro or in vivo, and at different scales, i.e., on a single cell, a smear, a droplet, or an aqueous portion of blood24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33. We perform a single cell investigation based on the use of a multi-modal imaging system. Several attempts have been presented to provide 3D quantitative imaging of dynamic microscopic samples. Amongst, digital holographic microscopy (DHM) has been shown to be the most effective one for quantitative phase-contrast imaging of dynamic biosamples within the diffraction limit resolution. DHM possesses several advantages; it is non-contact, non-invasive, label-free, easy-to-implement, and inexpensive method, and having single exposure nature it enables “3D live monitoring” or equivalently “quantitative phase imaging” of time-varying phenomena34. Transmission DHM has been widely applied for 3D imaging of biological cells and membranes25,35,36,37. DHM and some of the other quantitative phase imaging methods have been used to investigate the particulate pollution effects on cells38,39,40. DHM in reflective mode, on the other hand, is a suitable method for non-destructive and non-contact surface profile measurement41,42.

DHM system works on the basis of the interference of a reference laser beam and a beam passing through the object, known as object beam. The recorded interference pattern is called a hologram and the procedure is concluded by hologram reconstruction. The reconstruction of holograms recorded by a digital sensor is carried out numerically using a computer and eventually provides whole field information about the object under study. Due to the aforementioned nature of DHM, it is expected that the setup to be highly sensitive to environmental and mechanical vibrations. This, in turn, results in uncorrelated optical path length changes in the two arms of the interferometer leading to stronger noises. In order to overcome the problem, the self-referencing (SR) arrangements for DHM are suggested and attracted considerable attention in the last few years, which can be set up in various ways43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53. In this research we utilize a compact and simple SR-DHM setup based on the Gates’ interferometer54.

Whatever the optical visualization or detection method is used for RBC live monitoring, in order to maintain the cell in its natural environment and to minimize the effect of surfaces that the cell may adhere, one should combine the monitoring apparatus with an immobilization technique to hold a single cell. An elegant approach to immobilize micro-objects is the use of an optical trap or optical tweezers (OT). The method is invented and developed by Artur Ashkin55,56 and extensively used for several applications, improved in multiple directions, advanced in terms of minimum acting force, stiffest trap, and usage in extreme conditions, and also combined with other optical, mechanical, or chemical techniques56,57,58,59,60,61.

OT has been used to apply controlled forces on RBCs62,63,64, to stretch them65, or to hold them for other characterization methods66,67. DHM and OT are synergistic techniques as both deal with microscopic samples, and due to the possibility of their insertion in a conventional microscopy setup, their integration is straightforward25,68,69,70,71,72. Here, we integrate the DHM and OT methods on a Gates’ SR arrangement. Moreover, by addressing proper pre-designed diffractive optical elements (DOEs) onto a spatial light modulator (SLM) we generate multiple OTs73,74. This comes along with two advantages: (1) the non-spherical shaped objects like RBC usually try to align themselves with the beam axis in order to find the maximum volume of trapping region, which, in turn, obstructs clear imaging67,75. The use of multiple OTs overcomes the problem of RBC flipping. (2) Multiple OTs limit the possible photo-damages to the cell by distributing the trapping power more evenly throughout the volume25,59. In order to further reduction of the photo-damage of the trapping beam on the cell, we use an optical chopper to cut the beam periodically and build “blinking OT”, in which the cell is repeatedly trapped and released at a pre-controlled rate25,56,76.

The use of the comprehensive and integrated blinking and multiple OTs setup and SR-DHM system provides an advantageous platform for similar studies on single cells and other microscopic objects that need to be immobilized and 3D imaged. The details of the combined system and the numerical reconstruction procedure are explained in Section 2. The results are presented and discussed in Section 3, and the paper is concluded in Section 4.

Materials and methods

Sample preparation

Red blood cells

RBCs are obtained from the Blood Bank of Zanjan, Iran, and from freshly collected human blood, drawn from clinically healthy donors, from whom informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Blood Bank regulations. The plasma and the buffy coat of fresh blood are separated by centrifugation at 3000 g for 10 min at 4 \(^{\circ }\)C temperature, and the separated layers are removed by careful aspiration. The cells are resuspended in physiological solution (NaCL,150 mM), and are washed three more times with the same buffer, in order to obtain a 0.1% hematocrit value, which is the suitable concentration for microscopic experiments that require a single-cell or few cells in the field of view. The RBC specimens are kept in water bath at 37 \(^{\circ }\)C before the experiments. The experimental protocols are conducted in accordance with the regulations and policies and under approval of the Blood Bank of Zanjan, which are also in accordance with the regulations under WMA Declaration of Helsinki.

Nanoparticles

Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) in physiological solution is prepared separately in 10 mM concentration. For each round of measurement, this solution is added to the cell medium in a constant rate by infusing Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) solution directly into the cell chamber through a syringe pump. The syringes containing Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) in NaCl and NaCl are attached to the infusion pump motor in opposite directions to provide a push-pull infusion at the same flow rate, which enables controlling the concentration of the particles. Therefore, a specific amount of RBC normal buffer is replaced by Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) solution and the volume of the cell chamber is maintained at 1.5\(\times 10^{-7}\) m\(^3\) throughout the experiment. Once the concentration is adjusted, we wait for a minute to allow incubation of RBCs with Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) particles before the measurement.

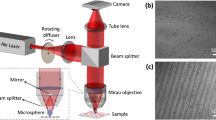

Self-referencing DHM integrated with the blinking multiple OTs setup; IS white light illumination source, L lens, M mirror, C condenser, S sample, DM dichroic mirror, MO microscope objective, BS beam splitter, NDF neutral density filter, CH optical chopper, PH pinhole, and SLM spatial light modulator, GBS Gates’ beam splitter. Inset: Magnified view of the RBC trapping arrangement.

Experimental procedure

Experimental setup

Figure 1 shows the experimental setup that we used to investigate the morphological effects of Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) particles on single RBCs. The setup provides three functions: bright field microscopy, DHM and blinking multiple OTs. The bright field microscopy illumination path is shown by yellow color. The white light illumination source (IS, halogen lamp, 6 V, 30 W), lens L\(_1\) (focal length = 5 cm), condenser (C), microscope objective MO (UPLFLN, Olympus, 100\(\times\), NA 1.3, Olympus), lens L\(_8\) (focal length = 7.5 cm), and Camera (DCC1545M, Thorlabs, 5.2 \(\mu\)m pixel pitch) provide bright field microscopy. The beam path indicated by red color shows the DHM part of the setup, from the laser source to the digital camera. A He-Ne laser (MEOS, 632.8 nm, 5 mW), is spatially filtered by the use of L\(_2\) (microscope objective, Olympus, 10\(\times\)) and the pinhole PH\(_1\) and collimated by the use of lens L\(_3\) (focal length = 10 cm) and directed onto the sample (S) using the beam splitter (BS, Thorlabs, BS010) and the condenser. The diffracted laser light from the sample is collected by MO and is sent to the SR module through mirror M\(_1\). The SR module is a Gates’ beam splitter (GBS, Thorlabs, BS016) which is a large area cube beam splitter mounted in a slightly tilted direction (\(\alpha\)). The mounting of GBS is so that the diffracted DHM laser beam hits the tilted corner. The lower half is refracted and transmitted and the upper half is reflected from the splitting coated interface of GBS and overlaps with the transmitted beam when leaves the GBS. Therefore, they interfere and the interference patten on the camera forms the hologram. Having few RBCs in the sample guarantees free of cell areas of object beam to act as a reference beam for the SR-DHM arrangement. Single RBCs are trapped by the use of OT. As we explained in the Introduction section, we use multiple blinking OTs to not only safely trap a single RBC, but also to avoid its flipping when it approaches to a trap site. Otherwise, it may potentially complicate imaging procedure. The OT laser beam path and the formed OTs in the setup is represented by green color. The OT laser beam (Melles Griot, MGL-III-532 DPSS laser, 300 mW, 532 nm) is cleaned by the set of the lens L\(_4\) (microscope objective, Olympus, 10\(\times\)) and the pinhole PH\(_2\), collimated by the use of lens L\(_5\) (focal length = 10 cm), and redirected at a quasi-normal angle by the mirror M\(_2\) to the SLM (Holoeye, PLUTO-2, phase only, reflective) to generate multiple OTs. Addressing a DOE from a computer onto the SLM is simply performed by considering the SLM as a second monitor. By addressing proper successive DOEs any required manipulation of multiple trap sites can be achieved. We address proper DOEs onto the SLM to form four separate and controllable OTs at the sample plane. The engineered beam is sent onto the sample via the set of lenses L\(_6\) (focal length = 10 cm) and L\(_7\) (focal length = 10 cm) equipped with a windowing pinhole PH\(_3\), dichroic mirror (DM, Thorlabs, DMLP605, longpass, cut-on wavelength = 605 nm), and the microscope objective MO. Indeed, the same microscope objective is used for all the three tasks of bright field imaging, DHM and OT. The use of DM is useful to reject the reflected OT laser beam, which in turn improves the imaging and DHM quality. In the experiments a single RBC is targeted while the IS and OT are on, and once it is trapped and well-focused the DHM laser is switched on and successive digital holograms are acquired. MO is adjusted so that the OT is formed at the height of 10 \(\mu\)m from the inner surface of the chamber. This would ensure that one can safely ignore the influence of hydrodynamic proximity of the cell to the chamber surfaces. The microfluidic chamber is a rectangular-shaped capillary tube (path length 400 \(\mu\)m, VitroCom) connected to a syringe pump (NE-1000 Programmable Single Syringe Pump). To increase the Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) concentration in the chamber of sample and in order to maintain the volume of the chamber a constant throughout the experiment, we use a push-pull add-on on the syringe pump, and in each concentration, which is pre-calculated, we infuse a particular amount of Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) directly into the chamber and withdraw physiological solution at a fixed rate67. Digital holograms are recorded at 0.05 s time intervals. The recorded digital holograms are subjected to numerical reconstruction. In the beginning of the experiments and to subtract the effect of possible contaminations, optical aberrations and noises, we acquire “reference” holograms. In the numerical reconstruction the associated phase to the reference digital hologram is subtracted from all the reconstructed holograms.

Diffractive optical element design for multiple OTs

Multiple OTs are generated by engineering and reshaping the laser beam in order to keep the single RBCs horizontally and to distribute the laser power more evenly for minimizing the photo-damages. This is done by addressing proper pre-designed DOEs on the SLM. A simple non-iterative method, based on the propagation and superposition of spherical waves, has been used to design DOEs for 3D multiple trapping with the control on the trap strength at each trap site77. In this approach, it is assumed that the DOE is illuminated by a set of point sources which emit spherical waves of different strengths. The complex amplitude right before the DOE plane is the superposition of these spherical waves. Similarly, the trap sites are considered as virtual point sources that generate spherical waves. The superposition of the back-propagated waves originated from the aforementioned virtual point sources will lead to the complex amplitude at the plane right after the DOE. Assuming that the DOE is a phase element, the difference between the phases of the complex amplitudes before and after the DOE is assigned as the DOE phase distribution to be addressed onto the SLM. For the RBC experiments, we use four trap sites depicted in the inset of Fig. 1.

Numerical processing of digital holograms

DHM through recording the interference of the transmitted beam and a reference beam provides quantitative phase information about the “phase objects”:

where \({E}_{0s}\) and \(\phi _{s}\), and \({E}_{0r}\) and \(\phi _{r}\) are the amplitudes and phases of the sample and the reference beams, respectively, and the direction of the \(\vec {E_0s}\) denotes the polarization. The phase difference, \(\phi _{s}-\phi _{r}\), is proportional to the optical path length difference of the two beams and can be used to measure the thickness of the transparent sample at any point (x, y), if the illumination is monochromatic and the variations in the refractive index of the sample are neglected. The core of the numerical reconstruction process is the diffraction integral. The process includes simulating the illumination of the recorded holograms by the reference laser beam followed by a diffraction into the plane where the image is planned to form. Angular spectrum propagation approach in scalar diffraction theory is shown to be a suitable method to perform the aforementioned processes78. In the reconstruction process the two terms of the recorded interference pattern after illumination by the reference beam include the whole information of the sample and leads to a virtual image and a real image. The other terms are the zero-order terms that cause noises in the final reconstructed images and have to be removed79. In the Fourier domain, these terms are filtered out and the modified light-wave, \(E_{s}^F(x,y,0)\), is obtained as:

where u and v are the spatial frequencies in x and y directions, respectively, and \(\tilde{E}_{s}(u,v)=\textrm{FT}\{E_s(x,y)\}\) denotes the Fourier transform of the light-wave at the holograms plane, \(E_s(x, y, z = 0)\). Complex amplitude at an arbitrary plane located at \(z=d\) is obtained by free space propagating of \(E_{s}(x,y,0)\) to a demanded distance d:

where \(\lambda\) is the wavelength of the laser beam. The whole angular spectrum propagation process can be summarized as the following:

\(\phi _{s}\), the phase of the object, and \(I_s\), the intensity of the object, are calculated from the complex amplitude as:

\(I_s(x,y,z)\) in Eq. (6) is, indeed, the intensity image similar to the image acquired by a conventional microscope. It is remarkable that a smoothing process on the obtained phase and amplitude can be also performed within the numerical reconstruction process. Equation (5) provides the phase-map of the object, which embeds the 3D information of phase objects. The phase map is proportional to the optical path length, \(\phi = \frac{2\pi }{\lambda } nL\), where n is the refractive index of the medium and L is the physical length that the light beam propagates. The phase changes when either the shape or the refractive index of the object under study is changed. Assuming negligible changes of the refractive index of the object, as we considered for the current research, the phase distribution directly leads to the surface 3D profile of it. Nevertheless, in cases that the objects undergo changes on both the physical thickness and the refractive index, instead of volume and related parameters, it is possible to define optical volume in analogy to optical path length, which is computed by multiplying the area by phase instead of hight, and monitor the variations of the optical volume to assess the sample. The phase obtained from Eq. (5) is in the range of [\(-\frac{\Pi }{2}\),\(\frac{\Pi }{2}\)], which due to the use of \(\arctan\) function, includes discontinuities throughout the phase map. The discontinued phases are converted to continuous phase maps by the unwrapping process. We use Goldstein’s branch-cut algorithm for phase map unwrapping80. We use a home-made user interface in Matlab® to perform the ASP approach for numerical image reconstruction. The usual hardwares of typical laptops or personal computers suffice for this task. The details on the process of DHM reconstruction can be found in our previous researches, e.g., in81,82.

Results and discussion

In the Gates-based DMH-OT setup, it is possible to optimize the objective for either DHM or OT as they both share a common propagation direction through the same microscope objective. Therefore, it is imperative to find a compromise between the two techniques during the experiments.

The initial control experiment involves infusing physiological solution at high rates for confirming that the trapped cells undergo negligible morphological changes in the absence of high Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) concentrations. However, the infusion velocity during the data acquisition is adjusted to the minimum rate, significantly lower than the rate used in the control experiment.

(a,b) 3D reconstructed images and 2D maps of a RBC at t= 0 and t= 180 s without particulate air pollutant, and (c,d) a RBC with particulate air pollutant, (e) 2D reconstructed map of the RBC with indicated arbitrary points without particulate air pollutant, (f) the cross-sectional profiles along the line indicated in panel (e), for the trapped RBC with and without particulate air pollutant, (g) the thickness change of individual RBCs with and without particulate air pollutant from t=0 to t=180 s at the typical points of M, N, and P indicated in panel (e).

The integration of the Gates-based common-path DHM setup with the blinking multiple OTs arrangement, as shown in Fig. 1, ensures one that the morphological changes in cells are solely induced by Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) rather than through likely photo-damage via the trapping beam, as the intensity of the trapping laser is distributed over the cell and also it blinks. However, in order to confirm that the morphological alterations in cells are induced exclusively by Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) solution, we conduct control experiments in which no solution is added to the RBC sample. The results of these controlling experiments are then compared with the Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) exposed ones. The experimental procedure, i.e., successful trapping of single RBCs and then monitoring after adding Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) particles is performed on over 100 RBCs in different samples. The quantitative assessment of morphometric features is performed by reconstructing the recorded digital holograms at various intervals after injection of Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\). In Fig. 2 the 3D reconstructed images of typical optically trapped RBCs in the beginning of the experiments and after t=180 s are shown. The horizontally positioned RBCs in the DHM images offer the most valid information when compared to single OT experiments. Figures 2(a) and 2(b) are the results of the control experiment in which no Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) is present in the environment of the RBCs. Figures 2(c) and 2(d) are similar 3D images and 2D maps for RBCs under presence of Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) particulate air pollutants in the solution. The substantial morphological changes of polluted RBC and the control one is obvious visually. Considering the quantitative feature of DHM, we measure the pollution induced morphological changes quantitatively toward gaining a deeper understanding of their behavior and properties. The cross-sectional profiles along lines in arbitrary directions, such as \(\overline{\mathrm{{AB}}}\) line shown in Fig. 2(e), can be compared in different times after the onset of experiments. Figure 2(f) shows the averaged cross-sectional thickness profiles of RBCs at t=0 (blue dots) and at t=180 s (red dashed lines) without (upper graph) and with (lower graph) the presence of Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) particles. Alternatively, we consider arbitrary points on different parts of the cell, such as points M, N, P on the 2D phase map of the examined RBCs in the Fig. 2(e), to quantitatively monitor in time. M is chosen from the margins of the RBC, N from the thin part (inner part of the disk) of the cell, and P from the thickest edge part. The procedure is repeated for several cells. In order to avoid the effect of possible unwanted dislodging of the trapped RBCs, the holograms are recorded at the frame rate of 20 fps, however, only the proper holograms of every 6 s are processed. Figure 2(g) shows the measured thickness in such points for 180 s. Each data point represents an average of at least 6 cells. In obtaining the thickness maps and cross-sectional profiles of the RBCs from the calculated phase maps we assume a relative refractive index of 1.1 for the RBC with respect to its environmental buffer83. Our results show dramatic changes within 180 s time of monitoring, induced by the presence of pollutants: the thickness at all typical chosen points is decreased within time despite the RBC without pollutant, which remains almost unchanged during the similar 180 s.

The observed changes in the morphology of the RBCs under influence of particulate pollutants can be expressed in more quantitatively fashion by calculating the roughness parameters. There are several parameters to describe the morphometry of any statistical distribution, from which we consider the ones listed in Table 184. Some of these parameters are calculated from the cross-sectional profiles and the rest is calculated using thickness information from the whole cell. In Table 1, \(h(x_i,y_j)\) is the thickness of the cell at a point \((x_i,y_j)\), M and N being the number of pixels in lateral dimensions, and the mean value is \(\bar{h}(x_i,y_j) =\frac{1}{M N} \sum _{i=1}^{M} \sum _{j=1}^{N}h(x_i,y_j)\). Sa and Sq are the spatial average and spatial root mean square, respectively, which are measures to the average distance from the mean value of data. Spatial maximum peak height, Sp, spatial maximum valley height, Sv, and spatial maximum height, St, however, do not contain averaging over the data, and are evaluated from the absolute minimum and maximum thickness of the cell. It is remarkable that measurement of Sv and St requires proper setting of the filtering mask in the Fourier spectrum during hologram reconstruction, to avoid erroneous extrema. Spatial skewness, Ssk, the third moment of the deviation, measures the degree of symmetry in roughness around the mean value; negative skew indicates a predominance of holes, while positive skew indicates a “peaky” surface. Spatial kurtosis, Sku, measures the thickness distribution throughout the cell, and is related to the width of the height distribution; smaller Sku values indicate broader distributions corresponding to gradually varying surfaces, i.e. free of extreme peaks or valley features, and greater values indicate the presence of inordinately high peaks or deep valleys. Spatial kurtosis, spatial skewness, and spatial root mean square are often measured together due to their synergistic information about the distribution. Parameters such as spatial average profile of slopes, Sda, and spatial root mean square profile of slopes, Sdq, provide complementary information on the roughness of the surfaces as they include the distribution of differentiations. They depend on the slope of thickness changes, which depends upon the cell surface area, and surface data grid, and hence provide information about the thickness changes of the “entire” cell surface.

The roughness parameters defined in Table 1 for RBCs (a-c) without and (d-f) with particulate air pollutant. Each data point is the average of at least 6 measured cells. The vertical axis, labeled as R/R\(_1\), depicts the values of the specified parameters in relation to their baseline measurements at t = 0. R\(_1\) in each panel denotes the initial values to which the depicted parameter has been normalized for a direct and facilitatory comparison of the effects.

The relative volume (V/V\(_1\), V\(_1\) being the volume at t = 0) change of individual RBCs with (red color dots) and without (blue color dots) particulate air pollutant. Each data point is the average of at least 6 measured cells. The volume of each cell is calculated through having the height information, derived from the hologram reconstruction and considering the equation \(\phi = \frac{2\pi }{\lambda } nL\), and multiplying the height of each pixel by the pixel area. The size of each pixel is obtained by a simple calibration test using a resolution test target (R3L3S1N, Thorlabs).

Based on the data extracted from the reconstruction of digital holograms, we examine the roughness parameters for 180 s experiment duration to determine the morphological changes happening to the trapped RBCs. Of course, considering multiple parameters provide more comprehensive understanding on the morphology changes. The results for the various roughness parameters outlined in Table 1 are comprehensively illustrated in Fig. 3. Each data point in these figures represents an average derived from a minimum of six measured cells, ensuring statistical validity. The vertical axis, labeled as R/R\(_1\), depicts the values of the specified parameters in relation to their baseline measurements at t = 0. R\(_1\) in each figure denotes the initial values to which the depicted parameter has been normalized for a direct and facilitatory comparison of the effects. Figure 3(a) focuses on the first-moment deviation and the absolute extrema values recorded at 10 s intervals following the commencement of the experiments involving RBCs that are not exposed to particulate pollution. To enhance the visibility of morphological changes, it may be beneficial to plot higher moments of deviation, which can provide deeper insights into the structural variations occurring within the cells. In Fig. 3(b), we present the second moment (root mean square, Sq), third moment (skewness, S sk), and fourth moment (kurtosis, S ku) of deviation for the RBCs without pollution exposure, elucidating further changes in cell morphology. Figure 3(c) showcases the slope-related roughness parameters of the intensity distribution, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of how these features are affected over time. Figures 3(d), 3(e), and 3(f) depict analogous results for RBCs subjected to the effects of particulate pollution. A significant observation emerges from the data; there is a stark contrast between the calculated parameters of normal RBCs, represented by blue dots in Figs. 3(a-c), and those of RBCs exposed to pollution, indicated by red dots in Figs. 3(d-f). This compelling difference underscores the dramatic morphological alterations induced by the presence of pollutants in the environment surrounding the cells. The deformability of the cells can be better indicated from the substantial decrease in the relative volume (V/V\(_1\), V\(_1\) being the volume at t = 0) with the presence of particulate pollution, shown in Fig. 4. Each data point is the average of at least six measured cells. The volume of each cell is calculated through having the height information, derived from the hologram reconstruction and considering the equation \(\phi = \frac{2\pi }{\lambda } nL\), and multiplying the hight of each pixel by the pixel area. The size of each pixel is obtained by a simple calibration test using a resolution test target (R3L3S1N, Thorlabs).

Morphological changes in RBC membrane show strong correlation with the presence of Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) particles in vicinity of the trapped RBC. These effects can be caused through local shrinkage of the cell membrane or decrease in its rigidity due to the presence of the attached external particles. Moreover, the effects may be attributed partly to the electro-magnetic interaction of Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) particles, the overload iron, with the hemoglobin molecules of the cell, and the induced oxidative damage in peripheral of the cells85. It is remarkable that the influence of temperature increase is excluded from the possible causes, following the strategy we follow to avoid temperature caused effects as well as performing the control experiments. The first cause for temperature increase is the direct effect of trapping laser power. Also, the possible light absorption by the Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) particles can induce temperature increase. Both effects have been already studied. Most optical trapping experiments use water or watery solutions, such as physiological solution, and laser powers on the order of 100 mW, leads to a temperature increase of about 1 K in the focus, given the absorption spectra of water and usual bio-samples86. By the use of multiple blinking OTs the effect is reduced down to a 10% of the temperature increase, which is neglected in our experiment, and this assumption is validated by performing the control experiments. Moreover, it is shown that the absorption of Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) particles in 532 nm is negligible87. Therefore, the generated heat by the particles in our experiments in turn can be neglected. The results collectively are in agreement with previous studies; the hematological effects of Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) nanoparticles have received particular attention due to the growing drug delivery applications of nanoparticles and, hence, the resulted potential safety concerns. Both cytotoxic and genotoxic effects have been explored. While it is shown that high concentration of these nanoparticles, enhances oxidative stress, reduces the cellular antioxidants, and alters the inflammatory system, but no significant genetic damage is reported88.

The presented setup and the roughness investigation procedure have the capability of being used for various single cell investigations, such as morphology based cell identification or study of the effect of important organic and synthetic compounds, such as cholesterol and lead, or external field effects, such as magnetic field effect, on structural properties of cells. Moreover, high-throughput single-cell analysis is a challenging task in flow cytometry, and in order to response to this requirement, in recent years DHM has been suggested as a label-free tomographic approach for observing, analyzing and separating objects in a liquid sample89,90. This is done by combining DHM with a microfluidic channel and by exploiting the random rolling of cells while they are flowing along the channel continuous-flow cytotomography, which is suitable for practical operation and has high throughput. Therefore, the DHM part of our method can be used for the cytometry oriented task itself. When, instead, the cell is immobilized by the use of OT the orientation of the cell can be more precisely and programmably done by reconfiguring the OT trap sites. To that end the present setup, which incorporates multiple OTs through addressing proper diffractive optical elements onto a SLM is very useful. Moreover, the integrated DHM-OT approach can be similarly used to study the effects of other types of pollution. Several clinical researches have demonstrated that the extended exposure to increasing levels of different particulate air pollution, such as wildfire smoke and lead-based particles, or non-particulate pollution, such as nitrogen dioxide, is associated with greater odds of anemia2. The association is modified by the place of residence, linking the anemia risk to the air pollution. Our approach may be generalized to provide a complementary single-cell investigation to the aforementioned clinical studies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we experimentally simulated the effect of particulate air pollution on red blood cells (RBCs). We investigated the impact of Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\), as the most dominant constituent of airborne pollution in big cities. The single RBCs are immobilized by a blinking multiple trap apparatus. Multiple traps along with blinking trapping laser light ensure minimization of possible laser caused photo-damages to the cells. The study on RBCs was performed through real-time morphometry of several individual cells exposed to particulate pollution. Also controlled experiments when the cells are in their normal physiological solutions were performed. The morphometry procedure includes acquisition of digital holograms of the cell in trap for over 3 min, 3D post-process reconstruction of the holograms, and computation of several morphometric and statistical parameters. The digital holography system is based on the self-referencing Gates’ arrangement, which is highly robust against environmental vibrations and noises. It also facilitates integration of holographic imaging setup with multiple blinking optical trapping setup. Our research has conclusively shown that injecting particles into the medium where RBCs are suspended causes a change in their structure and volume over time. It is evident that the surface structure of the RBC is highly altered and its roughness increases as a result of the presence of air pollutants in the medium. The effects are attributed to the local shrinkage of the cell membrane or decrease in its rigidity due to the presence of the attached external particles, and partly to the electro-magnetic interaction of Fe\(_3\)O\(_4\) particles with the hemoglobin molecules of the RBC, and the induced oxidative damage in peripheral of the cells. The presented integrated system and the experimental procedure have the capability of being used for various single cell investigations, such as morphology based cell identification or study of the effect of important compounds or external fields.

Data availability

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Goudie, A. S. & Viles, H. A. The Earth Transformed: An Introduction to Human Impacts on the Environment (Wiley, 2013).

Manisalidis, I., Stavropoulou, E., Stavropoulos, A. & Bezirtzoglou, E. Environmental and health impacts of air pollution: a review. Front. Public Health 8, 14 (2020).

Almetwally, A. A., Bin-Jumah, M. & Allam, A. A. Ambient air pollution and its influence on human health and welfare: an overview. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 24815–24830 (2020).

Olmo, N. R. S. et al. A review of low-level air pollution and adverse effects on human health: implications for epidemiological studies and public policy. Clinics 66, 681–690 (2011).

Bhattarai, G., Shrestha, S. K., Sim, H.-J., Lee, J.-C. & Kook, S.-H. Effects of fine particulate matter on bone marrow-conserved hematopoietic and mesenchymal stem cells: A systematic review. Exp. Mol. Med. 1–11 (2024).

Buzea, C., Pacheco, I. I. & Robbie, K. Nanomaterials and nanoparticles: Sources and toxicity. Biointerphases 2, MR17–MR71 (2007).

Rao, C. Environmental Pollution Control Engineering (New Age International, 2007).

Kim, K.-H., Kabir, E. & Kabir, S. A review on the human health impact of airborne particulate matter. Environ. Int. 74, 136–143 (2015).

Liu, N. M. et al. Evidence for the presence of air pollution nanoparticles in placental tissue cells. Sci. Total Environ. 751, 142235 (2021).

Yu, H., Yin, Y., Zhang, J. & Zhou, R. The impact of particulate matter 2.5 on the risk of preeclampsia: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 1–13 (2020).

an elementary cfd study. Zhang, T., Gao, B., Zhou, Z. & Chang, Y. The movement and deposition of pm2. 5 in the upper respiratory tract for the patients with heart failure. Biomed. Eng. Online 15, 517–530 (2016).

News code: 1400102922340, howpublished = https://www.isna.ir/news/1400102922340/ (Accessed 3 March 2022).

Shi, L. et al. Low-concentration pm2.5 and mortality: Estimating acute and chronic effects in a population-based study. Environ. Health Perspect. 124, 46–52 (2016).

Badman, D. G. & Jaffé, E. R. Blood and air pollution; state of knowledge and research needs. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 114, 205–208 (1996).

Duruibe, J. O. et al. Heavy metal pollution and human biotoxic effects. Int. J. Phys. Sci. 2, 112–118 (2007).

Terzano, C., Di Stefano, F., Conti, V., Graziani, E. & Petroianni, A. Air pollution ultrafine particles: toxicity beyond the lung. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 14, 809–821 (2010).

Wadhwa, R. et al. Red blood cells as an efficient in vitro model for evaluating the efficacy of metallic nanoparticles. 3 Biotech 9, 1–15 (2019).

Sun, J. et al. Cytotoxicity, permeability, and inflammation of metal oxide nanoparticles in human cardiac microvascular endothelial cells. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 27, 333–342 (2011).

Gonet, T. & Maher, B. A. Airborne, vehicle-derived fe-bearing nanoparticles in the urban environment: A review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 9970–9991 (2019).

Gonet, T., Maher, B. A. & Kukutschová, J. Source apportionment of magnetite particles in roadside airborne particulate matter. Sci. Total Environ. 752, 141828 (2021).

Braun, A. et al. Impact of ferrocene on the structure of diesel exhaust soot as probed with wide-angle x-ray scattering and c (1s) nexafs spectroscopy. Carbon 44, 2904–2911 (2006).

Filippelli, G. M., Laidlaw, M. A., Latimer, J. C. & Raftis, R. Urban lead poisoning and medical geology: An unfinished story. GSA Today 15, 4–11 (2005).

Liati, A., Pandurangi, S. S., Boulouchos, K., Schreiber, D. & Dasilva, Y. A. R. Metal nanoparticles in diesel exhaust derived by in-cylinder melting of detached engine fragments. Atmos. Environ. 101, 34–40 (2015).

Khalid, A. In Vitro Studies on the Toxicity of CuO and Silver Nanoparticles. Ph.D. thesis, Aligarh Muslim University (2014).

Farzam Rad, V., Tavakkoli, R., Moradi, A.-R., Anand, A. & Javidi, B. Calcium effect on membrane of an optically trapped erythrocyte studied by digital holographic microscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 083701 (2017).

Pope, C. A. III. & Dockery, D. W. Health effects of fine particulate air pollution: Lines that connect. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 56, 709–742 (2006).

Brunekreef, B. & Holgate, S. T. Air pollution and health. Lancet 360, 1233–1242 (2002).

Brook, R. D. et al. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the expert panel on population and prevention science of the american heart association. Circulation 109, 2655–2671 (2004).

Donaldson, K., Stone, V., Seaton, A. & MacNee, W. Ambient particle inhalation and the cardiovascular system: potential mechanisms. Environ. Health Perspect. 109, 523–527 (2001).

Valavanidis, A., Fiotakis, K. & Vlachogianni, T. Airborne particulate matter and human health: toxicological assessment and importance of size and composition of particles for oxidative damage and carcinogenic mechanisms. J. Environ. Sci. Health C 26, 339–362 (2008).

Pham, B. T. et al. The interaction of sterically stabilized magnetic nanoparticles with fresh human red blood cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 10, 6645 (2015).

Shahzad, A. et al. Air pollution and respiratory health among men exposed to two different environs as occupational exposure. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 30, 833–840 (2020).

Bor-Kucukatay, M., Wenby, R. B., Meiselman, H. J. & Baskurt, O. K. Effects of nitric oxide on red blood cell deformability. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 284, H1577–H1584 (2003).

Kim, M. K. Principles and techniques of digital holographic microscopy. SPIE Rev. 1, 018005 (2010).

Lee, K. et al. Quantitative phase imaging techniques for the study of cell pathophysiology: from principles to applications. Sensors 13, 4170–4191 (2013).

Marquet, P., Depeursinge, C. & Magistretti, P. J. Exploring neural cell dynamics with digital holographic microscopy. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 15, 407–431 (2013).

Farzam Rad, V., Moradi, A.-R., Darudi, A. & Tayebi, L. Digital holographic microscopy of phase separation in multicomponent lipid membranes. J. Biomed. Opt. 21, 126016–126016 (2016).

Kim, J., Go, T. & Lee, S. J. Volumetric monitoring of airborne particulate matter concentration using smartphone-based digital holographic microscopy and deep learning. J. Hazard. Mater. 418, 126351 (2021).

Kang, S. H. et al. Interactions of nanoparticles with macrophages and feasibility of drug delivery for asthma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 1622 (2022).

Cho, M. J., Kim, C.-E., Shin, Y. H., Kim, J. K. & Pack, C.-G. Influence of chemical and genetic manipulations on cellular organelles quantified by label-free optical diffraction tomography. Anal. Chem. 95, 13478–13487 (2023).

Rad, V. F., Khamedi, R. & Moradi, A.-R. The effect of martensite volume fraction on topography of dual phase steels. Mater. Lett. 239, 21–23 (2019).

Pourvais, Y., Asgari, P., Moradi, A. & Rahmani, O. Nondestructive analysis of advanced materials nonlinear behavior using digital projection moiré. In Three-Dimensional Imaging, Visualization, and Display 2014, vol. 9117, 91171B (International Society for Optics and Photonics, 2014).

Chhaniwal, V., Singh, A. S., Leitgeb, R. A., Javidi, B. & Anand, A. Quantitative phase-contrast imaging with compact digital holographic microscope employing lloyd’s mirror. Opt. Lett. 37, 5127–5129 (2012).

Mosaviani, R., Moradi, A.-R. & Tayebi, L. Effect of humidity on liquid-crystalline myelin figure growth using digital holographic microscopy. Mater. Lett. 173, 162–166 (2016).

Vora, P. et al. Wide field of view common-path lateral-shearing digital holographic interference microscope. J. Biomed. Opt. 22, 126001 (2017).

Abbasian, V., Rasouli, S. & Moradi, A.-R. Microsphere-assisted self-referencing digital holographic microscopy in transmission mode. J. Opt. 21, 045301 (2019).

Anand, A., Chhaniwal, V. & Javidi, B. Tutorial: common path self-referencing digital holographic microscopy. APL Photonics 3, 071101 (2018).

Aakhte, M. et al. Microsphere-assisted super-resolved mirau digital holographic microscopy for cell identification. Appl. Opt. 56, D8–D13 (2017).

de Groot, P. J. & Biegen, J. F. A new class of wide-field objectives for 3d interference microscopy. In Optical Measurement Systems for Industrial Inspection IX, vol. 9525, 133–139 (SPIE, 2015).

Kemper, B. et al. Monitoring of laser micromanipulated optically trapped cells by digital holographic microscopy. J. Biophotonics 3, 425–431 (2010).

Barroso, Á. et al. Three-dimensional exploration and mechano-biophysical analysis of the inner structure of living cells. Small 9, 885–893 (2013).

Girshovitz, P. & Shaked, N. T. Compact and portable low-coherence interferometer with off-axis geometry for quantitative phase microscopy and nanoscopy. Opt. Express 21, 5701–5714 (2013).

Merola, F. et al. Biolens behavior of rbcs under optically-induced mechanical stress. Cytometry A 91, 527–533 (2017).

Picazo-Bueno, J., Trusiak, M. & Micó, V. Single-shot slightly off-axis digital holographic microscopy with add-on module based on beamsplitter cube. Opt. Express 27, 5655–5669 (2019).

Ashkin, A. & Dziedzic, J. M. Optical trapping and manipulation of viruses and bacteria. Science 235, 1517–1520 (1987).

Jones, P., Maragó, O. & Volpe, G. Optical Tweezers (Cambridge University Press Cambridge, 2015).

Moffitt, J. R., Chemla, Y. R., Smith, S. B. & Bustamante, C. Recent advances in optical tweezers. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 77, 205–228 (2008).

Reihani, S. N. S. & Oddershede, L. B. Optimizing immersion media refractive index improves optical trapping by compensating spherical aberrations. Opt. Lett. 32, 1998–2000 (2007).

Petrov, D. V. Raman spectroscopy of optically trapped particles. J. Opt. A Pure Appl. Opt. 9, S139 (2007).

Shabestari, M. H., Meijering, A., Roos, W., Wuite, G. & Peterman, E. Recent advances in biological single-molecule applications of optical tweezers and fluorescence microscopy. Methods Enzymol. 582, 85–119 (2017).

Wang, X. et al. Enhanced cell sorting and manipulation with combined optical tweezer and microfluidic chip technologies. Lab Chip 11, 3656–3662 (2011).

Zhang, H. & Liu, K.-K. Optical tweezers for single cells. J. R. Soc. Interface 5, 671–690 (2008).

Modery-Pawlowski, C. L., Tian, L. L., Pan, V. & Sen Gupta, A. Synthetic approaches to rbc mimicry and oxygen carrier systems. Biomacromolecules 14, 939–948 (2013).

Ghosh, A. et al. Euler buckling-induced folding and rotation of red blood cells in an optical trap. Phys. Biol. 3, 67 (2006).

Guck, J. et al. The optical stretcher: a novel laser tool to micromanipulate cells. Biophys. J . 81, 767–784 (2001).

Creely, C. M., Volpe, G., Singh, G. P., Soler, M. & Petrov, D. V. Raman imaging of floating cells. Opt. Express 13, 6105–6110 (2005).

Moradi, A., Ali, M., Daneshpanah, M., Anand, A. & Javidi, B. Detection of calcium-induced morphological changes of living cells using optical traps. IEEE Photonics J. 2, 775–783 (2010).

DaneshPanah, M. et al. 3d holographic imaging and trapping for non-invasive cell identification and tracking. J. Display Technol. 6, 490–499 (2010).

Cardenas, N. & Mohanty, S. K. Optical tweezers assisted quantitative phase imaging led to thickness mapping of red blood cells. Appl. Phys. Lett.103 (2013).

Kim, K., Yoon, J. & Park, Y. Simultaneous 3d visualization and position tracking of optically trapped particles using optical diffraction tomography. Optica 2, 343–346 (2015).

Liu, J., Zhu, L., Zhang, F., Dong, M. & Qu, X. Microdeformation of rbcs under oxidative stress measured by digital holographic microscopy and optical tweezers. Appl. Opt. 58, 4042–4046 (2019).

Utadiya, S. et al. Integrated self-referencing single shot digital holographic microscope and optical tweezer. Light Adv. Manuf. 3, 453–465 (2022).

Grier, D. G. A revolution in optical manipulation. Nature 424, 810–816 (2003).

Dufresne, E. R. & Grier, D. G. Optical tweezer arrays and optical substrates created with diffractive optics. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 69, 1974–1977 (1998).

Grover, S., Gauthier, R. C. & Skirtach, A. Analysis of the behaviour of erythrocytes in an optical trapping system. Opt. Express 7, 533–539 (2000).

Magazzù, A. et al. Experimental investigation of critical casimir forces in binary liquid mixtures by blinking optical tweezers. In Optical Trapping Applications, OtW4D–4 (Optical Society of America, 2017).

Moradi, A.-R., Ferrari, E., Garbin, V., Di Fabrizio, E. & Cojoc, D. Strength control in multiple optical traps generated by means of diffractive optical elements. Optoelectron. Adv. Mater. Rapid Commun. 1, 158–161 (2007).

Goodman, J. W. Introduction to Fourier Optics (Roberts and Company publishers, 2005).

Hariharan, P. Optical Holography: Principles, Techniques and Applications (Cambridge University Press, 1996).

Gutmann, B. & Weber, H. Phase unwrapping with the branch-cut method: Role of phase-field direction. Appl. Opt. 39, 4802–4816 (2000).

Farzam Rad, V. & Moradi, A.-R. Flat wall proximity effect on micro-particle sedimentation in non-newtonian fluids. Sci. Rep. 10, 2741 (2020).

Fathi, N., Moradi, A.-R., Habibi, M., Vashaee, D. & Tayebi, L. Digital holographic microscopy of the myelin figure structural dynamics and the effect of thermal gradient. Biomed. Opt. Express 4, 950–957 (2013).

Bhabhor, G. D., Patel, C., Chhillar, N., Anand, A. & Lad, K. N. Geometrical characterization of healthy red blood cells using digital holographic microscopy and parametric shape models for biophysical studies and diagnostic applications. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 57, 355401 (2024).

Abbasian, V., Akhlaghi, E. A., Charsooghi, M. A., Bazzar, M. & Moradi, A.-R. Digital holographic microscopy for 3d surface characterization of polymeric nanocomposites. Ultramicroscopy 185, 72–80 (2018).

Gaharwar, U. S. et al. Iron oxide nanoparticles induced oxidative damage in peripheral blood cells of rat. J. Biomed. Sci. Eng. 8, 274 (2015).

Peterman, E. J., Gittes, F. & Schmidt, C. F. Laser-induced heating in optical traps. Biophys. J . 84, 1308–1316 (2003).

Bahjat, H. H., Ismail, R. A. & Sulaiman, G. M. Photodetection properties of populated fe3o4 tio2 core-shell/si heterojunction prepared by laser ablation in water. Appl. Phys. A 128, 8 (2022).

Shah, A. & Dobrovolskaia, M. A. Immunological effects of iron oxide nanoparticles and iron-based complex drug formulations: Therapeutic benefits, toxicity, mechanistic insights, and translational considerations. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 14, 977–990 (2018).

Merola, F. et al. Tomographic flow cytometry by digital holography. Light Sci. Appl. 6, e16241–e16241 (2017).

Jooris, S. & Mathuis, P. Flow cytometer with digital holographic microscope. US Patent 10,578,541 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mojtaba Khorasani for his assistance in preparation of the samples. V.F.R. and A.R.M. appreciate the partial support provided by the Iran National Science Foundation (INSF), Grant No. 97001326.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.F.R. carried out the experiments. V.F.R. and M.M. performed the numerical reconstruction. All authors analyzed and interpreted the data, and contributed to the manuscript preparation. A.R.M. conceived and supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rad, V.F., Mohammadi, M. & Moradi, AR. Morphometric effects of particulate air pollution on an optically trapped single red blood cell. Sci Rep 15, 16068 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00955-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00955-x