Abstract

Lunar regolith is an unconsolidated fine-grained layer overlaying on the entire lunar surface, formed by continuous impact and space weathering processes. The production of lunar regolith is both related to the protolith internal properties and the external gardening primarily modulated by impact flux. The penetrating radar data of Chang’E-5 is used to investigate the subsurface structures and the production and evolution of lunar regolith at the landing site. Together with the penetrating radar results from Chang’E-3, we found that the regolith production rates on the ejecta blanket of fresh craters are faster than Apollo sites. The speed up of the regolith production for Chang’E-3 and Chang’E-5 sites may be due to the increased impact flux during the recent history of the solar system, that also recorded by the impact beads and the fragile nature of the ejecta blanket at the two sites. The result of this article can be highly beneficial to the radar signal processing and further explanation of Chang’E-6.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The lunar surface is covered by a layer of fine-grained regolith, formed by continuous space weathering and impact bombardment processes, which records the surface-space interactions on the Moon1,2,3,4. The lunar regolith has been studied by the returned samples in the lab and by in-situ investigations including lunar penetrating radar, which has tremendous capabilities to unravel the subsurface structures of the Moon. Chang’E-3 mission conducted the first in-situ Lunar Penetrating Radar exploration in the northwestern Imbrium basin, with wide frequency bands and high spatial resolutions5. The CE-3 LPR data indicates multi-layered regolith, ejecta, and Eratosthenian-aged and Imbrian-aged basaltic bedrocks underneath, which significantly improves our understanding of the lunar volcanic history6,7. Furthermore, Chang’E-4 mission, landed in the Von Kármán crater, South Pole-Aitken basin, conducted the first in-situ LPR exploration on the farside of the Moon, deciphering multi-layered regolith as well as ejecta8,9. The Lunar Regolith Penetrating Radar has also been installed on the Chang’E-5 sample-return mission, which includes 12 off-ground high-resolution Vivaldi antennas on the bottom of the lander, with a detecting depth of ~ 4.5 m and a resolution of 5 cm10,11. The strong detection ability of LRPR onboard CE-5 cannot only be used to study the regolith structures and production rate with respect to time, but also for supporting the drilling and sampling operations, as well as the ongoing sample analysis.

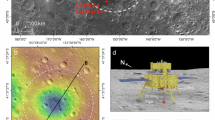

The CE-5 landing site is located to the northern Oceanus Procellarum (Fig. 1) from one of the youngest mare basalts1,2 named Em4/P5812,13. There are two episodes of mare eruptions, including Imbrian-aged low-Ti mare basalts underneath, overlaid by Eratosthenian-aged intermediate-Ti mare basalts12,14 (Fig. 2). The regolith on the Eratosthenian-aged basalts surrounding the CE-5 site was estimated to be 4–6 m thick15, which may be admixed with exotic materials from distant craters including Harpalus, Copernicus, Aristarchus and Mairan G15. CE-3 landed on another young mare unit on the Moon at northwestern Mare Imbrium, with an age of ~ 2.5 Ga3. The CE-3 landing site is located to the Eratosthenian-aged high-Ti basalts in northwestern Mare Imbrium (Fig. 1), overlaying on the Imbrian-aged low-Ti basalts6,7, which are exposed at a distance of < 10 km to the northeast of the landing site. The Eratosthenian-aged basalts at CE-3 landing site have a regolith thickness of 6–7 m16,17, slightly thicker than the CE-5 site. The CE-3 landing site is ~ 50 m from the eastern rim of the ~ 450 m diameter Zi Wei crater with an age of ~ 27–80 Ma7, and CE-5 is ~ 200 m from the eastern rim of the ~ 419 m diameter Xu Guangqi crater with an age of ~ 60 Ma15. Both of them were constrained by the crater size frequency distribution measurements which has been tested by the Apollo samples of impact craters18. Both of CE-3 and CE-5 landed on the continuous ejecta blanket of young lunar craters, which provides unprecedented opportunities to study how the nature of protolith and impact flux influence the formation of lunar regolith.

Based on the level 2B data, the LPPR data underwent decoding, denoising and background removal (see Fig. 3). The amplitudes of signals in the radar data are highly dependent on the dielectric constants of the lunar regolith and rocks, which are primarily influenced by their porosities and compositions6,7,19. Strong reflections occur at boundaries between the fine regolith, the ejecta layer, the brecciated bedrock zones, and bedrocks, or within the ejecta layer and the brecciated bedrock zones8. Weak reflections occur within a few of scattered rock clasts while no reflection is expected to be observed in the fine regolith or homogeneous basalts8,20. After filtering the LRPR data, more advanced processing of the LRPR data, including Kirchhoff migration21 with envelope processing under electromagnetic wave velocity of 1.983 m/ns and time–frequency ridge detection22,23 were conducted to enhance the reliability of the depths and shapes of the reflectors. Thus, the detailed shallow subsurface stratigraphy of the landing site was then obtained as shown in Fig. 4.

The LRPR data processing. (a) The original 132 traces of LRPR data sequenced according to the antenna offsets. (b) Pre-processing results of the LRPR data. Processing procedures include DC removal, cable delay correction, and background removal. (c) Comparison of the influence of background removal on LRPR data preprocessing. The vertical axis refers to two-way travel time and the horizontal axis is the number of traces and the grayscale indicates amplitude.

LRPR data processing using the Kirchhoff migration and ridge detection method within ~ 4.5 m of burial depth. (a) Kirchhoff migration on recovering the true depths and shapes of the subsurface structures. Signals envelopes were calculated using the Hilbert transform along depths, which are used to unravel lunar regolith thickness and structures. (b) Improved LRPR data from time–frequency slices at the central frequency after ridge detection. Black dotted lines represent the drilling location and the red dotted line represents the depth of obstacles encountered while drilling. Black arrows indicate the main delamination position of units A-D and the blue arrows indicate the detailed delamination position in Unit A.

Results

The substructure at the CE-5 landing site was divided into four stratigraphic units according to the amplitude/energy distribution of the reflections: strong reflection (Unit A), sub-strong reflection (Unit B), weak reflection (Unit C) and subtle reflection (Unit D) units from top to bottom with a total depth of ~ 4.5 m (Fig. 4). Units A and C are mainly composed of disordered fragmented rocks as shown by lengthy ridges with tilt direction as shown in Fig. 4b, which reflects the sizes and arrangement modes of the fragmented rocks. From Unit B to Unit C, the number of fragmented rocks decreases with depth.

The Unit D at the bottom has a thickness of ~ 0.7 m with subtle reflections, suggesting relatively homogeneous compositions. This unit corresponds to the Eratosthenian-aged bedrock (see Figs. 2 and 4) that can be extended to a depth of ~ 51 m14. Therefore, Unit D could represent the young mare bedrock that were sampled by CE-5 with an age of ~ 2.0 Ga1,2. The weak reflection unit (Unit C), with a thickness of ~ 1.3 m, lies directly on the mare basalt unit (Unit D), showing few internal and holonomic reflectors. Unit C could be a transition zone that contains rock breccia/fractured basalts and lunar regolith (Fig. 4). During the exposure to the lunar surface before the onset of Units A and B, coherent mare basalt at the base (Unit D) were fractured to produce a paleo-regolith layer and admixed with coming ejecta, producing this transition zone. The sub-strong reflection unit (Unit B), with a thickness of ~ 1.0 m, shows a small number of observed reflectors, indicating rocks mixed with probably ejecta from the top (Unit A). The strong reflection unit (Unit A), with a thickness of ~ 1.5 m, shows abundant and cluttered reflections when compared with that of the lower Unit B (Fig. 4), suggesting abundant rock boulders.

As indicated by the relative location of the CE-5 lander and the adjacent impact craters (Fig. 1c), CE-5 landed on the proximal ejecta of Xu Guangqi crater15. Furthermore, considering that Xu Guangqi crater is the most prominent and the youngest impact crater next to the CE-5 landing site, the abundant rocks appearing in Unit A are very likely the ejecta materials from Xu Guangqi crater (Fig. 4), overlaying on the more matured lunar regolith (Unit C). The regolith in Unit B has been mixed with boulders from Xu Guangqi ejecta on the top (Unit A), whereas Unit C contains few fractured rocks from the underlying mare basalts (Unit D). Both Unit B and Unit C represent lunar regolith layer developing on the concrete Em4/P58 mare basalts with an age of 2.0 Ga1,2. It has been known that the impact of the Xu Guangqi crater only excavated ~ 35 m-deep materials based on empirical relationship between the crater excavation depth and crater diameter, which cannot penetrate through the ~ 51 m-thick Em4/P58 mare basalts14. Thus, CE-5 samples, with a drilling depth up to ~ 0.9 m, largely represents the local mare basalts24.

Unit A, the CE-5 drilling zone composed of the ejecta from Xu Guangqi crater, shows complex internal structures and are further divided into three sublayers (Fig. 5a and b). The top sublayer is ~ 0.2 m thick and is homogeneous with fewer scatters, indicating fine-grained materials with a scarcity of rock boulders developing on the ejecta of Xu Guangqi. This top layer may be totally mixed by rapid gardening to form mature lunar soils25 despite the geologically young age as inferred by the CE-5 in situ Lunar Mineralogical Spectrometer data26. The middle sublayer is characterized by strong reflections with a thickness of ~ 1 m, suggesting the presence of large size of rock boulders or fragments from the ejecta of Xu Guangqi. The bottom sublayer is ~ 0.3 m thick and shows relatively weak reflections, indicating the presence of fewer rock fragments with contribution from underlying older lunar regolith.

The subsurface structures of the topmost layer shown by the LRPR data is further tested by the pulling force of the drill for the top ~ 1 m collected in the drilling operation25, for the first time in planetary explorations. The pulling force represents the feedback in contact with the underground materials during the CE-5 drilling samples, which could be an indicator of the size of the rock encountered. The analysis of LRPR data shows a strong reflection at a depth of ~ 0.75 m, interpreted to be due to the presence of fragmented rocks (Fig. 5a). This high rock abundance layer was also recorded by drilling at a depth of ~ 0.753 m, which leads to the dramatic increase of pulling force (Fig. 5a and b). The drill also encountered several large pulling force feedback positions (red arrows, Fig. 5a), which are highly consistent with the Kirchhoff migration and ridge detection results. The well-defined subsurface structures are consistent with expectations of shallow structures for the regolith at the CE-5 site, which support the upper layer of lunar regolith are controlled by the adjacent crater ejecta6,8. The consistency between the LRPR data analysis and the drilling results strengthened our stratigraphic interpretation at the sampling site and also validated reliability of the proposed processing procedures of LRPR data in this study.

Based on an age of ~ 60 Ma for Xu Guangqi15 and inferred ~ 0.2 m thick regolith on the landing site, we estimate the regolith production rate to be ~ 3.3 mm/Myr. Unit B and Unit C, as the paleo-regolith layer on the ~ 2.0 Ga Eratosthenian-aged concrete basalts1,2 have a total thickness of ~ 2.3 m, yielding a regolith production rate of ~ 1.1 mm/Myr. In addition, CE-3 landed on the proximal ejecta of a fresh crater (Fig. 1b), Zi Wei, with an age of ~ 27–80 Ma7 at the boundary between Eratosthenian-aged and Imbrian-aged mare basalts3. The shallow stratigraphy of the CE-3 site is very similar to the CE-5 site because of their similar geological settings3,26. For the top 20 m of the CE-3 site, four layers from the bottom to the top including a transition zone between the paleo-regolith and the concrete Eratosthenian-aged mare basalts, a paleo-regolith layer, the ejecta from Zi Wei crater, and a reworked zone formed on the ejecta layer of Zi Wei, have been resolved based on CE-3 LPR data. Forming on the ejecta blanket of Zi Wei, the regolith layer has a thickness of ~ 1 m, with an accumulation rate of ~ 5–10 mm/Myr considering the age of Zi Wei27. And the paleo-regolith layer at the CE-3 site is located between 4–11 m27 with a production rate of ~ 2.8 mm/Myr in the ~ 2.5 Ga exposure history on the lunar surface3.

Methods

Lunar regolith penetrating radar onboard CE-5

The LRPR is one of the main payloads on the CE-5 lander, which was deployed to detect lunar regolith thickness and subsurface structures at the landing site to support the drilling and sampling tasks11,12. The LRPR is a time-domain carrier-free picoseconds impulse surface penetrating radar with a Full Width at Half Maximum of 200 ps, which is 90 cm from the lunar surface and operates with frequency ranges of 1–3 GHz11. The LRPR was operated in-situ under static status, with one antenna sending pulse signals and 11 antennas receiving echo signals. The 12 antennas produced 132 traces of data in one operation period, and each trace has a time window of ~ 55 ns with a temporal sampling interval of 18.3 ps10. Interior structures of the lunar regolith and other subsurface structures were analyzed by the electromagnetic waves reflected from the subsurface. Electromagnetic waves are determined mainly by compositions (for example, FeO and TiO2 contents, see Fig. 6) and porosities of the regolith and other subsurface materials based on the multi-offset migration results, that the LRPR could be effectively used to detect the boundaries between the porous lunar regolith, ejecta, basalt lava layers, and bedrock. The lunar regolith and ejecta layers often contain large rock boulders, that signals reflected by the interfaces of these large boulders were detected6.

The LRPR is installed at the bottom of one edge of the lander, which consists of 12 separate antennas with a center working frequency of 2 GHz. Intervals of the array #1–10 is 12 cm and the distance between antenna #7 and #8 is 58.45 cm. Antenna #11 is in the same plane as antennas #1 ~ 10, which is ~ 90 cm from the lunar surface, and 12 cm from antenna #8. Antenna #12 is installed by the side of the lander, which is 16.75 cm, 5.24 cm, and ~ 107.25 cm from the planes of antennas #1–10, antenna #7 and the lunar surface, respectively. The longest dimension of the antenna array provides a synthetic aperture of ~ 1.554 m and the diameter of the drill pipe is 3.27 cm.

Preprocessing of the LRPR data

The original 132 traces of LRPR data were sequenced according to the antenna offsets are shown in Fig. 3a. Pre-processing procedures for the LRPR traces consist of DC removal, cable delay correction, and background removal based on level 2B data. The level 2B dataset has be added geometric positioning information based on level 2A dataset. The level 2A dataset is performed relative calibration, normalization, elimination of variable gain and the effect of instrument drift based on level 01 dataset. The level 01 dataset is based on the level 0B dataset after the numerical conversion of instrument parameters such as temperature, voltage, and current, and then reorganized according to the detection cycle. We apply a sixth-order Butterworth bandpass filter between 1 and 3 GHz on each trace and remove the background (Fig. 3b). Figure 3c shows that background removal has a great influence on LRPR data preprocessing.

Kirchhoff migration

Migration technology is an important wavefield signal processing method, which is essential for extracting weak signals to produce high-accuracy images of subsurface structures28,29. Migration method is widely used in seismic exploration, which a variety of migration methods were developed to meet different exploration needs. Seismic migration methods can also be applied to electromagnetic wave signal data processing that electrical field component of the electromagnetic wave is consistent with seismic wave equation. Migration methods had been applied to process the LPR data from the Chang’E-3 and Chang’E-4 missions6,8, which verified that migration methods are effective and applicable for high-resolution imaging of the complex subsurface structures and objects in the lunar regolith.

Seismic migration methods are divided into different types according to various implementation methods, such as Kirchhoff migration30, Stolt migration31, phase-shift migration32 and reverse time migration33,34. Among these methods, Kirchhoff migration is a stable and fast migration algorithm21, which is less dependent on the migration model, and has strong adaptability. In addition, Kirchhoff migration is flexible, which is able to meet processing requirements of irregular observation systems35. Based on these advantages, the Kirchhoff migration for the LRPR data is applied in this study to image structures of lunar regolith.

The theoretical basis of high-frequency electromagnetic wave Kirchhoff migration is to solve the electric field \(E\left( {x,y,z;t} \right)\) that satisfies the scalar wave equation through the integration method36.

where x, y, z represent spatial coordinates and \(t\) \(t\) represents time coordinate; \(v\) is the electromagnetic wave velocity. The Kirchhoff integral solution of the wave equation at the point \(\left( {x_{0} ,y_{0} ,z_{0} } \right)\) have two solutions: the upgoing wavefield and the downgoing wavefield. For the upgoing wavefield,

and for the downgoing wavefield,

where \(\Omega\) is the set of points on the surface, \(r\) is the distance from point \(\left( {x_{0} ,y_{0} ,z_{0} } \right)\) to the point of \(\Omega\). According to the exploding source principle28, when \(t\) is equal to 0, the electric field represents the migration result. Therefore, the Kirchhoff migration formula is

where \(E\left( {x,y,0;{{2r} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{2r} v}} \right. \kern-0pt} v}} \right)\) represents the received electromagnetic wave signal. The Kirchhoff migration formula (4) is applicable to electromagnetic wave data acquired by a single pulse and for the LRPR data acquired by multiple pulses, the value for each pulse needs to be superimposed.

Introduction of the ridge detection method

Ricker wave pulse signals are created and radiated to the lunar regolith through antennas of the LRPR. Images of the lunar regolith thickness and structures can then be generated according to the backward travelling waves from the spots or interfaces. Travel time of the electromagnetic waves has important effect on high-resolution imaging. To improve imaging quality of the lunar regolith and substructure, it is key to derive accurate arrival time of the backward electromagnetic waves37. Time–frequency analysis methods, e.g., short-time Fourier transform and continuous wavelet transform, are designed to expand the time-series signals to two-dimensional time–frequency domain38. The joint time–frequency characteristics can be extracted from conventional time–frequency representation. However, conventional methods often have difficulty to achieve the best resolution simultaneously in both time and frequency due to the Heisenberg-Gabor uncertainties, which implies that it is impossible to extract the precise time information from the representation generated by conventional methods alone. To overcome this limitation, this study presents a post-processing technology to extract the precise arrival time of the backward electromagnetic waves, which benefits high-resolution imaging in this study.

The Fig. 7a and c show the waveform and frequency spectrum of a simulated Ricker wave at the time instant 0 s, and the central frequency of the signal is 10 Hz. The STFT is used to generate the time–frequency representation of the signal (Fig. 7b). Results show that the time–frequency characteristic has a highly smeared distribution in both time and frequency directions. For an impulse-like signal22,39, it can be modeled from the following frequency expression:

where \(\hat{s}\left( \omega \right)\) denotes the Fourier transform of the signal, \(A\left( \omega \right)\) and \(\varphi \left( \omega \right)\) are the signal amplitude and phase in frequency domain, and \(- \varphi^{\prime}\left( \omega \right)\) is a group delay parameter. The GD can be used to determine the arrival time instant of the signals for each frequency point22. However, it is necessary to improve the energy concentration of the time–frequency representation to obtain higher accuracies. Recent studies indicate that the GD can be regarded as the ridges of the STFT along the frequency direction22,23 implying that it is possible to estimate the GD from the ridges of the time–frequency representation created by STFT. To obtain the STFT of the signal \(\hat{s}\left( \omega \right)\), a local frequency model is needed and written as

where \(\exists \varepsilon\) is assumed to be sufficiently small, \(\left| {A^{\prime}\left( \omega \right)} \right| \le \varepsilon\) and \(\left| {\varphi^{\prime\prime}\left( \omega \right)} \right| \le \varepsilon\) for \(\forall \omega\). Substituting this model into STFT, we derive

where \(g\left( {} \right)\) is the sliding even window function \({\text{supp}} \left( g \right) \in [ - \Delta ,\Delta ]\), and \(\hat{g}\left( {} \right)\) denotes the Fourier transform of the window function. The spectrogram of the signal can be obtained as

The STFT processing of a simulated Ricker wave. (a) The time-series waveform of a simulated Ricker wave. (b) Time–frequency representation of the signal generated by STFT. (c) The frequency spectrum of the signal. The STFT has the capacity to expand one-dimensional signals into two-dimensional time–frequency domain. However, the time–frequency energy has a large distribution, which has negative effect to determine accurate travel time of the reflected electromagnetic waves.

It is known from this equation that the time–frequency energy of the signal has a large distribution along the GD trajectory. Amplitude of the spectrogram reaches the maximum along the GD trajectory for each frequency point. This inspires that the GD trajectory can be estimated using the ridge detection method when the following two expressions \({{\partial \left| {G\left( {t,\omega } \right)} \right|} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\partial \left| {G\left( {t,\omega } \right)} \right|} {\partial t}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\partial t}} = 0\) and \({{\partial^{2} \left| {G\left( {t,\omega } \right)} \right|} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\partial^{2} \left| {G\left( {t,\omega } \right)} \right|} {\partial t^{2} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\partial t^{2} }} < 0\) are satisfied at the same time40,41,42.

To improve the energy concentration, spectrogram in the GD trajectory is retained and other coefficients are removed as shown in Fig. 8a. The new time–frequency representation only appears at the GD trajectory when compared to the large spread of the STFT spectrogram. The slice of the new representation at the central frequency is then used to determine the precise time instant when the impulse signal appears (Fig. 8b). Central frequency of the time–frequency representation can be detected using the following expression

Ridge detection processing. (a) The time–frequency representation using ridge detection. (b) The time–frequency slice at the central frequency point compared to the original Ricker wave. The time–frequency representation after ridge detection has a highly energy concentrated distribution, which can be used to abstain the precise travel time of the Ricker wave.

The slice at the central frequency can then be used to generate higher-resolution images of the lunar regolith thickness and structures than that of the original time-series waveform of the backward electromagnetic waves.

Conclusions

All Apollo mare landing sites have a regolith growth rate smaller than 2 mm/Myr according to seismic data43,44,45. Our analysis indicates that the estimated regolith production rate on the proximal ejecta of Xu Guangqi crater at the CE-5 site and of Zi Wei crater44 at the CE-3 landing site is 2–7 times faster than the regolith production rate of Apollo mare landing sites. In addition, for both the CE-3 and CE-5 landing sites, the regolith production rate on the proximal ejecta is much faster than that on the concrete mare basalts. These results suggest that the protolith plays an important role on the regolith formation, i.e., regolith production rate on the ejecta layer fragmented by the impact process is faster than that on the concrete mare basalts.

In addition, the production rate of lunar regolith generally decreases with time due to the decreasing impact flux46. The rate was estimated to be 5 mm/Myr in 4.0–3.5 Ga ago, 2 mm/Myr in 3.5–3.0 Ga ago, and 1 mm/Myr in 3.0–0 Ga ago based on the observations of impact craters by SELENE46. However, previous study has shown that there may be an increase of lunar impact flux in the recent 100 Ma due to the catastrophic breakup of the parent body of the Baptistina asteroid family in the main belt47. The speed up of the regolith production for CE-3 and CE-5 landing sites may also be due to the increased impact flux in the past 100 Ma48. The chronology study of the impact melt beads in the CE-5 soils by U–Pb isotopes indicates there are 17 age groups of impact melt beads47, corresponding well with the ages of the terrestrial Chicxulub crater, a cluster of Late Eocene craters, and some ordinary chondrite meteorites47,49,50. It indicates an increase of inner solar system impact flux would change the regolith production rate on the Moon.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Che, X. et al. Age and composition of young basalts on the Moon, measured from samples returned by Chang’e-5. Science 374, eabl7957 (2021).

Li, Q. L. et al. Two billion-year-old volcanism on the Moon from Chang’E-5 basalts. Nature 600, 54 (2021).

Zhao, J. et al. Geologic characteristics of the Chang’E-3 exploration region. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 57, 569–576 (2014).

Lucey, P. et al. Understanding the lunar surface and Space-Moon interactions. Rev. Mineral. Geochem 60, 83–219 (2006).

Fang, G. Y. et al. Lunar Penetrating Radar onboard the Chang’e-3 mission. Res. Astron. Astrophys. 14, 1607–1622 (2014).

Zhang, J. H. et al. Volcanic history of the Imbrium basin: A close-up view from the lunar rover Yutu. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 5342–5347 (2015).

Xiao, L. et al. A young multilayered terrane of the northern Mare Imbrium revealed 204 by Chang’E-3 mission. Science 347, 1226–1229 (2015).

Zhang, J. H. et al. Lunar regolith and substructure at Chang’E-4 landing site in South Pole-Aitken basin. Nat. Astron. 5, 1–6 (2021).

Li, C. L. et al. The Moon’s farside shallow subsurface structure unveiled by Chang’E-4 Lunar Penetrating Radar. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay6898 (2020).

Feng, J. Q. et al. An imaging method for Chang’e-5 Lunar Regolith Penetrating Radar. Planet. Space Sci. 167, 9–16 (2019).

Li, Y. X. et al. The imaging method and verification experiment of Chang’E-5 Lunar regolith penetrating array radar. IEEE Geosci. Remote. Sens. Lett. 99, 1–5 (2018).

Qian, Y. Q. et al. China’s Chang’e-5 landing site: Geology, stratigraphy, and provenance of materials. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 561, 116855 (2021).

Hiesinger, H. et al. Ages and stratigraphy of lunar mare basalts: A synthesis. Spec. Pap. Geol. Soc. Am. 477, 1–51 (2011).

Qian, Y. Q. et al. Young lunar mare basalts in the Chang’e-5 sample return region, northern Oceanus Procellarum. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 555, 116702 (2020).

Qian, Y. Q. et al. Copernican-aged (<200Ma) impact ejecta at the Chang’e-5 landing site: Statistical evidence from crater morphology, morphometry, and degradation models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL095341 (2021).

Qian, Y. Q. et al. The Long Sinuous Rille System in Northern Oceanus procellarum and its relation to the Chang’e-5 Returned Samples. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, 11 (2021).

Qiao, L. et al. Subsurface structures at the Chang’e-3 Landing Site: Interpretations from orbital and in-situ imagery data. Int. J. Earth Sci. 27, 707–715 (2016).

Hiesinger, H. et al. How old are young lunar craters?. J. Geophys. Res. Planets https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JE003935 (2012).

Neish, C. D. et al. Spectral properties of titan’s impact craters imply chemical weathering of its surface. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 3746–3754 (2015).

Lv, W. M. et al. Comparative analysis of reflection characteristics of lunar penetrating radar data using numerical simulations. Icarus 350, 113896 (2020).

Docherty, P. A brief comparison of some Kirchhoff integral formulas for migration and inversion. Geophysics 56, 1164–1169 (1991).

Yu, G. & Lin, T. R. Second-order transient-extracting transform for the analysis of impulsive-like signals. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 147, 107069 (2021).

Yu, G. A concentrated time–frequency analysis tool for bearing fault diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 69, 371–381 (2019).

Zhou, C. et al. Scientific objectives and payloads of the lunar sample return mission—Chang’E-5. Adv. Sp. Res. 69, 823–836 (2022).

Deng, X. J. et al. Design and implementation of sampling, encapsulation, and sealing system of Chang’E-5. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 51, 753–762 (2021).

Qian, Y. Q. et al. Geology and scientific significance of the Rümker Region in Northern Oceanus Procellarum: China’s Chang’E-5 Landing Region. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 123, 1407–1430 (2018).

Fa, W. Z. et al. Regolith stratigraphy at the Chang’E-3 landing site as seen by lunar penetrating radar. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 10179–10187 (2015).

Claerbout, J. F. Imaging the Earth’s Interior (Blackwell Scientific, 1985).

Yilmaz, Ö. Seismic Data Processing (Society of Exploration Geophysicists, 1987).

Schneider, W. A. Integral formulation for migration in two and three dimensions. Geophysics 43, 49–76 (1978).

Stolt, R. Migration by Fourier transform. Geophysics 43, 23–48 (1978).

Gazdag, J. Wave equation migration with the phase-shift method. Geophysics 43, 1342–1351 (1978).

Baysal, E. et al. Reverse time migration. Geophysics 48, 1514–1524 (1983).

Liu, H. et al. Two-dimensional reverse-time migration applied to GPR with a 3-D-to-2-D data conversion. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 10, 4313–4320 (2017).

Jäger, C. et al. True-amplitude Kirchhoff migration from topography. SEG Tech. Progr. Expand. Abstracts 22, 909–912 (2003).

Roberts, R. L. & Daniels, J. J. Modeling near-field GPR in three dimensions using the FDTD method. Geophysics 62, 1114–1126 (1997).

Morlet, J. et al. Wave propagation and sampling theory–Part I: Complex signal and scattering in multilayered media. Geophysics 47, 203–221 (1982).

Mallat, S. A. Wavelet Tour of Signal Processing. The Sparse Way (Academic Press, 2008).

Boashash, B. Time-Frequency Signal Analysis and Processing: A Comprehensive Reference (Academic Press, 2015).

Delprat, N. et al. Asymptotic wavelet and Gabor analysis: Extraction of instantaneous frequencies. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 38, 644–664 (1992).

Carmona, R. A. et al. Characterization of signals by the ridges of their wavelet transforms. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 45, 2586–2590 (1997).

Stanković, L. et al. Instantaneous frequency in time–frequency analysis: Enhanced concepts and performance of estimation algorithms. Digital Signal Process. 35, 1–13 (2014).

Cooper, M. R. et al. Lunar near-surface structure. Rev. Geophys. 12, 291–308 (1974).

Nakamura, Y. et al. Shallow lunar structure determined from the passive seismic experiment. Moon 13, 57–66 (1975).

Stöffler, D. & Ryder, G. Stratigraphy and isotope ages of lunar geologic units: Chronological standard for the inner solar system. Space Sci. Rev. 96, 9–54 (2001).

Ishiyama, K. et al. Estimation of the permittivity and porosity of the lunar uppermost basalt layer based on observations of impact craters by SELENE. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 118, 1453–1467 (2013).

Long, T. et al. Constraining the formation and transport of lunar impact glasses using the ages and chemical compositions of Chang’e-5 glass beads. Sci. Adv. 8, eabq2542 (2022).

Bottke, W. F. et al. An asteroid breakup 160 Myr ago as the probable source of the K/T impactor. Nature 449, 48–53 (2007).

Cui, Z. et al. A sample of the Moon’s far side retrieved by Chang’e-6 contains 2.83-billion-year-old basalt. Science 386, 1395–1399 (2024).

Che, X. et al. Isotopic and compositional constraints on the source of basalt collected from the lunar far side. Science 387, 1306 (2025).

Acknowledgements

Gang Yu is funded by NSFC grant 62271230. Yuqi Qian is funded by Hong Kong RGC grants JLFS/P-702/24 and 17308023. Yong Pang is funded by NSFC grant 12472358.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yu Gang wrote the main manuscript text,Pang Yong prepared the figures, Qian Yuqi and Xu Menglong reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, G., Pang, Y., Xu, M. et al. Chang’E-5 radar reveals fast regolith production at landing site. Sci Rep 15, 16507 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00994-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00994-4