Abstract

This paper investigates how plants respond to stress caused by asbestos cement products in irrigation water. It presents a thorough evaluation of the exposure and risk factors for plants, water, and soil when exposed to these materials. The experimental results provide empirical evidence of plant stress responses based on physiological and germination parameters. The research is motivated by concerns about environmental contamination from asbestos cement in irrigation water, which can be toxic to plants and lead to soil pollution, negatively impacting vegetation and soil quality. When exposed to asbestos in water, plants experience toxic stress that can inhibit photosynthesis, nutrient uptake, and germination. Asbestos can also adversely affect cell division and metabolism, risking plant growth, reproduction, and overall health, as well as making them more susceptible to disease and pests under environmental stress. The paper examines the impact on germination and physiological parameters of Trifolium pratense, Medicago sativa, and Solanum lycopersicum, particularly how they were affected by pre-established concentrations of irrigation water mixed with asbestos cement during a controlled germination experiment. The research methodology was developed in the absence of established global practices, standards, and methods, creating an opportunity for further methodological advancement. The findings could serve as a situational analysis for professionals in environmental plant protection and analytical fields.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Asbestos is a collective term for naturally occurring fibrous minerals that were extensively utilized in construction and industry due to their ability to withstand high temperatures and provide insulation. These minerals exhibit durability and cost-effective, but they represent potential health risks when inhaled as airborne particles1. Inhalation of asbestos fibres can lead to respiratory illnesses, including asbestosis, lung cancer, and Mesothelioma malignum2. The presence of asbestos in older structures has been identified as a continuing cause for concern3. Asbestos pollution has profound ramifications for environmental wellbeing, especially in soil and water ecosystems.

Asbestos has been shown to significantly affect environmental health, particularly regarding soil and water quality.

The release of asbestos fibres into the environment can contaminate the soil, thereby jeopardizing land-based ecological systems. Soil contamination can contribute to the spread of asbestos through wind erosion or surface runoff, leading to the dispersal of fibres into new areas4,5,6. The enduring nature and resilience of asbestos in the surrounding areas require comprehensive supervision, correction, and precautionary actions to reduce additional environmental and public health consequences7.

Asbestos cement products, especially roofing materials, are a major source of asbestos contamination in the environment due to their gradual deterioration. Asbestos cement products, particularly asbestos cement roofing, were widely used due to their durability and resistance to fire and weather. These products consist of a mixture of cement and asbestos fibres, providing structural strength. However, over time, these roofs become increasingly vulnerable to erosion and degradation, leading to the release of asbestos fibres into the environment. Factors such as age, weather conditions, and physical damage can exacerbate this erosion8. The deterioration and wearing away of asbestos cement roof materials result in the release of sizable amounts of harmful asbestos fibres into the nearby surroundings. These fibres can endure for extended periods due to their strong resistance to natural degradation processes9. Weathering mechanisms like freeze-thaw cycles, acid rain, and ultraviolet radiation expedite the decomposition of these substances, leading to a higher rate of fibre release10,11,12. These fibrous materials can be transported by the wind and distributed in soil or adjacent water sources13. Deteriorating roofing can release asbestos fibres, which may contaminate the nearby soil and water, thereby posing serious health risks to human and animal populations14,15. Rainwater collected from these roofs has the risk of being contaminated with asbestos fibres, making it unsuitable for drinking or irrigation and possibly causing pollution in local groundwater sources16,17,18. Additionally, the asbestos fibres may settle on plants and vegetation, potentially being incorporated into the food web if these plants are consumed by livestock or wildlife19.

Chrysotile asbestos, a component of cement roofing, can be released into water as fibres when the cement materials deteriorate. This release is mainly caused by weathering and erosion processes, during which rainwater or surface runoff carries the asbestos fibres away from their original location17. In water, chrysotile asbestos is less durable than other forms, but it can still persist and remain suspended for significant periods due to its fibrous nature9. Asbestos fibres that are released into the environment not only present risks to human health and soil quality, but also have direct and indirect impacts on plant physiology and growth.

Investigations into the impacts of asbestos on plants, especially those cultivated for gardens and agriculture, have uncovered multiple effects. Exposure to asbestos fibres can inhibit seed germination, likely due to the abrasive nature of the fibres disrupting seed coats and impeding water uptake17. Plants that do germinate may display stunted shoot and root growth because of fibrous asbestos inhibiting the development of root systems, affecting nutrient and water absorption9. The number of leaves a plant produces may also be reduced, likely due to impaired photosynthesis and overall vitality20. Biochemical factors of plants, such as the level of proteins, may be negatively impacted by exposure to asbestos. The abrasive properties of asbestos fibres along with their chemical reactions can disturb regular metabolic activities. When plant tissues are exposed to soil contaminated with asbestos, the protein content frequently diminishes due to the inhibition of crucial nutrient uptake by the fibres, leading to physiological strain21. The presence of asbestos fibres in soil also correlates with reduced chlorophyll content, which can impair photosynthesis and lead to reduced plant vigor and yield20. Furthermore, root development can be significantly impacted, as fibres physically obstruct root elongation or chemically disrupt normal root function22. Additionally, oxidative stress caused by asbestos exposure can lead to the generation of reactive oxygen species (abbreviation: ROS), which can damage cellular components, further reducing biochemical functions like protein synthesis and leaf growth23. Exposure to asbestos poses a distinct challenge to plant life, emerging as a novel environmental element in modern times. The gritty and fibrous quality of asbestos has the potential to disturb cellular arrangements, leading to physical harm in root and leaf tissues. This dual impact results in decreased nutrient absorption, compromised protein production, and overall inhibited growth, culminating in a comprehensive reaction to this stressor21. Runoff from deteriorating asbestos cement products can mobilize fibres into collected rainwater, making it a potential hazard when used for irrigation or other purposes17. Thus, understanding and mitigating the impact of asbestos on plant stress responses is critical for safeguarding agricultural productivity and ecosystem health in a changing climate. Given these environmental and biological impacts, it is crucial to further investigate how asbestos contamination influences plant stress responses and broader ecological dynamics.

Table 1 presents a comprehensive summary of the relevant literature necessary for establishing the research background of this paper. This summary aims to delineate the existing body of knowledge regarding the effects of chrysotile asbestos on vegetation, thereby clarifying the novelty of the current research. By consolidating previous studies, this overview identifies gaps in the literature and emphasizes the significance of the present investigation. Such an approach ensures that the findings of this research are situated within the broader academic discourse, illustrating how it contributes to advancing the understanding of the relationships between environmental contaminants and plant life. Ultimately, this summary underscores the innovative aspects of the paper, positioning it as an important contribution to the field.

The novelty and gap-filling nature of this research can be emphasized by noting that previous literature has typically focused on either the contamination of soil samples taken from polluted sites or analysed aquatic environments. This research integrates these two approaches by examining the various aspects of chrysotile asbestos presence in precipitation and its effects on the soil-plant system. The novelty of this research lies in its comprehensive evaluation of plant stress responses to asbestos cement contamination in irrigation water during the early vegetation phases, an area with limited established global practices and standards. Additionally, there is a notable international gap in that most studies concentrate solely on pure asbestos fibres, overlooking the fact that chrysotile’s high surface tension and charge can lead to the formation of complex associations. A key recognition of this paper is that plants do not encounter pure chrysotile but rather chemically and physically altered complexes or composite formations, which influence their bioavailability and toxic effects. Furthermore, in cases of heavy metal contamination, synergistic effects may occur, which are often disregarded. This paper differs from previous work by employing a multi-faceted approach, integrating lab-based germination and growth experiments with advanced analytical techniques to assess asbestos effects on plants. While earlier studies focused on free asbestos fibres in soil and water, this research examines the impact of asbestos cement particles in irrigation water, simulating real-world contamination. The experimental design uses precise dose-response analyses to evaluate physiological and biochemical stress indicators in plants, while statistical modelling enhances the reliability of findings by quantifying the relationship between asbestos exposure and plant responses. The other novelty of the research lies in the fact that it investigates the combined effect of asbestos-cement matrix, a topic that has been studied only minimally in the literature. Moreover, existing research does not adequately address the involvement of horticulture, further highlighting the significance of the current paper. Thus, this research not only sheds new light on the effects of chrysotile asbestos but also provides a more comprehensive understanding of its impacts on soil-plant systems, particularly focusing on horticulture and the complexities of environmental interactions. Despite the scarcity of such studies, this research provides new insights into the environmental risks posed by asbestos contamination, advances methodological approaches, and offers valuable situational analysis for professionals in environmental plant protection and analytical fields.

Materials and methods

The paper analysed the germination parameters and diversity of three varieties of Trifolium pretense (Salino, Rozeta, Altaswede), Medicago sativa (Emiliana, Gea, Algonquin) and Solanum lycopersicum (Manó, Kecskeméti 549, Mobil). It also evaluated their variability to validate the adverse effects of asbestos cement contaminated irrigation water on plant growth in a controlled experiment using distilled water. The Trifolium pratense and Medicago sativa seeds were procured from Pannon-Mag-Agrár Kft., whereas the Solanum lycopersicum seeds were acquired from Garafarm Trade Kft. The results indicated a significant reduction in both the rate and percentage of germination across all Trifolium pratense, Medicago sativa and Solanum lycopersicum varieties. The selected plant species - Solanum lycopersicum, Trifolium pratense, and Medicago sativa - have relevance beyond their agricultural importance, as they can serve as models to address critical environmental and water management concerns. Solanum lycopersicum was chosen due to its significance in horticulture and its potential to accumulate contaminants when irrigated with water from aging asbestos cement channels, which poses risks to food safety. Trifolium pratense is particularly pertinent in the context of urban green spaces, where the use of greywater for irrigation is an emerging practice, necessitating further assessment of plant resilience and contaminant uptake. Medicago sativa, widely cultivated in arable farming, is crucial for evaluating the risks associated with irrigation infrastructure constructed from asbestos cement materials, which may contribute to pollutant exposure. These plant species, therefore, serve as valuable models for understanding the implications of alternative water sources and irrigation systems on both agricultural and ecological sustainability.

Conditions and arrangement for germination experiment

Three different varieties of Trifolium pratense, Medicago sativa and Solanum lycopersicum were investigated to assess the effects of stress induced by varying doses. The seeds were sterilized on the surface using 2.0% NaOCl for a duration of 2 min, followed by three rinses with sterile distilled water. Subsequently, batches consisting of 10 seeds each were placed in individual sterile Petri dishes containing a moistened cotton disc. Each treatment dose was represented by five petri dishes for analysis (N = 5 × 10). There are a total of 350 test items for each type (N = 7 × 50). The germination experiment was conducted under controlled laboratory conditions to ensure reproducibility. The Petri dishes housing the seeds were maintained at a consistent temperature of 22 ± 1 °C, monitored using a digital temperature controller. The system utilized built-in LED illumination optimized for plant growth, providing a full-spectrum light source. The LED setup, powered via an adjustable USB-A to USB-C connection, enabled programmable light cycles with seven-step dimmable intensity settings. The photon flux density at plant level was maintained at a maximum of 50 lm. The ventilation system was designed to ensure appropriate airflow regulation.

Preparation of sample solutions

During this analysis, asbestos cement products were examined that commonly utilized in Hungary, which contained chrysotile asbestos with an average composition ranging from 8.00 to 10.0%, and a cement content of 90.0–92.0%. It was essential to simultaneously investigate these specific characteristics due to their combined effects on the erosion and deterioration of the product matrix. Solutions at various concentrations (1.00 mg/l, 2.00 mg/l, 5.00 mg/l, 10.0 mg/l, 25.0 mg/l, and 50.0 mg/l) were prepared using doubly distilled water in a laboratory setting for analysis purposes. To prepare the extract, asbestos cement samples were first mechanically ground into fine particles. The resulting powder was then suspended in doubly distilled water at predetermined concentrations and incubated for 24 h at ambient temperature. After the extraction process, the suspensions were filtered through a 0.45 μm filter to remove larger particles while retaining the asbestos fibres and colloidal components. The resulting solutions were stored in sterile glass containers under dark conditions at 4 °C until needed for further analysis. The control group underwent treatment with double-distilled water. Seeds were subjected to their assigned dosage and treatment method during the experiment.

Germination assessment

Throughout the analysis, we consistently monitored the germination rate, germination time, and the root length and shoot height of plants. Root length was measured from the point of contact with the cotton disc’s surface to the tip of the primary root, while shoot height measurements were taken on day 31 for each sample. These parameters were assessed utilizing a Burg-Wächter Precise PS-72,150 digital caliper (0 mm to 150 mm range) to ensure precise data on development. Each treatment was replicated multiple times, and our findings are reported as mean values ± standard error. The obtained data was examined in terms of percentages. The statistical significance of the results was evaluated using ANOVA analysis performed in Excel, with a significance level threshold of 0.05 to determine if the findings were statistically significant.

Results

Results of Trifolium pratense analysis

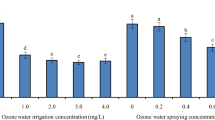

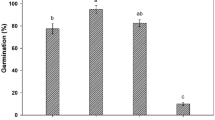

The control germination rate is 88.0% for Salino, 86.0% for Rozeta and 90.0% for Altaswede. Germination of Trifolium pratense seeds at 25.0 °C under light and dark conditions averaged 88.0 ± 2.00%. The tested samples showed that already at a dose concentration of 1 mg/l the germination rate was reduced to 82.0% in the case of the Salino, 80.0% for Rozeta and 84.0% for Altaswede. This was reduced to 48.0% (Salino), 46.0% (Rozeta) and 58.0% (Altaswede) at the 50 mg/l dose, and to 54.5% (Salino), 53.5% (Rozeta) and 64.4% (Altaswede) as a percentage of the control group. The average value for the whole group is 93.2 ± 0.16% for 1.00 mg/l and 57.5 ± 6.04% for 50 mg/l at the percentage of control group. The average difference in the effect of the two dose concentrations is −35.7 ± 5.90%. The coefficient of determination of Salino is 0.9840, while 0.9974 for Rozeta and 0.9313 for Altaswede. The dose effect of 1 mg/l resulted in a reduction to 95.2% in root length compared to the control group in Salino (Fig. 1). This rate was 95.7% for Rozeta and 95.5% for Altaswede. The values as a percentage of the control group because of the 50 mg/l dose effect was 47.6% for Salino, 47.8% for Rozeta, and 54.5% for Altaswede. This represented an average of 95.4 ± 0.21% (1.00 mg/l) and 50.0 ± 3.94% (50.0 mg/l). The coefficient of determination of Salino is 0.9791, while 0.9941 for Rozeta and 0.9611 for Altaswede.

Comparative examination of root length in Trifolium pratense cultivars (Salino, Rozeta, and Altaswede) exposed to asbestos-contaminated irrigation water. Significant reductions in root length were observed at both 1 mg/l and 50 mg/l concentrations (p ≤ 0.05), with greater inhibition at higher doses. The reduction was most prominent in the 50 mg/l dose, where root length was reduced to 47.6% (Salino), 47.8% (Rozeta), and 54.5% (Altaswede) compared to the control group.

The dose effect of 1 mg/l resulted in a reduction to 91.3% in height of the shoot compared to the control group in Salino (Fig. 2). This value was 90.5% for Rozeta and 93.2% for Altaswede. The average value as a percentage of the control group because of the 50 mg/l dose effect was 41.3% for Salino, 45.2% for Rozeta, and 45.5% for Altaswede. The average of 1.00 mg/l dose affect is 91.7 ± 1.39% and for 50.0 mg/l is 44.0 ± 2.34%. The coefficient of determination of Salino is 0.9439, while 0.9662 for Rozeta and 0.9828 for Altaswede.

Comparative examination of shoot height in Trifolium pratense cultivars (Salino, Rozeta, and Altaswede) exposed to asbestos-contaminated irrigation water. Significant reductions in shoot height were observed at both 1 mg/l and 50 mg/l concentrations (p ≤ 0.05), with greater inhibition at higher doses. The reduction was most prominent in the 50 mg/l dose, where shoot height was reduced to 41.3% (Salino), 45.2% (Rozeta), and 45.5% (Altaswede) compared to the control group.

Results of Medicago sativa analysis

The control germination rate is 92.0% for Emiliana, 94.0% for Gea and 90.0% for Algonquin. Germination of Medicago sativa seeds at 25.0 °C under light and dark conditions averaged 92.0 ± 2.00%. The tested samples showed that already at a dose concentration of 1 mg/l the germination rate was reduced to 88.0% in the case of the Emiliana and Gea, while it was 86.0% for Algonquin. This was reduced to 54.0% (Emiliana), 50.0% (Gea) and 52.0% (Algonquin) at the 50 mg/l dose, and to 58.7% (Emiliana), 53.2% (Gea) and 57.8% (Algonquin) as a percentage of the control group. The average value for the whole group is 94.9 ± 1.15% for 1.00 mg/l and 56.6 ± 2.95% for 50 mg/l at the percentage of control group. The average difference in the effect of the two dose concentrations is −38.4 ± 1.81%. The coefficient of determination of Emiliana is 0.9827, while 0.9842 for Gea and 0.9754 for Algonquin. The dose effect of 1 mg/l resulted in a reduction to 97.2% in root length compared to the control group in Emiliana (Fig. 3). This rate was 97.1% for Gea and 91.4% for Algonquin. The values as a percentage of the control group because of the 50 mg/l dose effect was 59.7% for Emiliana, 60.3% for Gea, and 57.1% for Algonquin. This represented an average of 95.2 ± 3.30% (1.00 mg/l) and 59.1 ± 1.68% (50.0 mg/l). The coefficient of determination of Emiliana is 0.9781, while 0.9788 for Gea and 0.9844 for Algonquin.

Comparative examination of root length in Medicago sativa cultivars (Emiliana, Gea, and Algonquin) exposed to asbestos-contaminated irrigation water. Significant reductions in root length were observed at both 1 mg/l and 50 mg/l concentrations (p ≤ 0.05), with greater inhibition at higher doses. The reduction was most prominent in the 50 mg/l dose, where root length was reduced to 59.7% (Emiliana), 60.3% (Gea), and 57.1% (Algonquin) compared to the control group.

The dose effect of 1 mg/l resulted in a reduction to 98.8% in height of the shoot compared to the control group in Emiliana (Fig. 4). This value was 96.3% for Gea and 96.4% for Algonquin. The average value as a percentage of the control group because of the 50 mg/l dose effect was 65.9% for Emiliana, 69.1% for Gea, and 69.9% for Algonquin. The average of 1.00 mg/l dose affect is 97.2 ± 1.41% and for 50.0 mg/l is 68.3 ± 2.14%. The coefficient of determination of Emiliana is 0.9818, while 0.9604 for Gea and 0.9429 for Algonquin.

Comparative examination of shoot height in Medicago sativa cultivars (Emiliana, Gea, and Algonquin) exposed to asbestos-contaminated irrigation water. Significant reductions in shoot height were observed at both 1 mg/l and 50 mg/l concentrations (p ≤ 0.05), with greater inhibition at higher doses. The reduction was most prominent in the 50 mg/l dose, where shoot height was reduced to 65.9% (Emiliana), 69.1% (Gea), and 69.9% (Algonquin) compared to the control group.

Results of Solanum lycopersicum analysis

The control germination rate is 92.0% for Manó and 90.0% for Kecskeméti 549 and Mobil. Germination of Solanum lycopersicum seeds at 25.0 °C under light and dark conditions averaged 90.7 ± 1.15%. The tested samples showed that already at a dose concentration of 1 mg/l the germination rate was reduced to 88.0% in the case of the Manó and Kecskeméti 549, while 86.0% for Mobil. This was reduced to 58.0% (Manó), 60.0% (Kecskeméti 549) and 56.0% (Mobil) at the 50 mg/l dose, and to 63.0% (Manó), 66.7% (Kecskeméti 549) and 62.2% (Mobil) as a percentage of the control group. The average value for the whole group is 96.3 ± 1.26% for 1.00 mg/l and 64.0 ± 2.36% for 50 mg/l at the percentage of control group. The average difference in the effect of the two dose concentrations is −32.4 ± 1.13%. The coefficient of determination of Manó is 0.9909, while 0.9823 for Kecskeméti 549 and 0.9916 for Mobil. The dose effect of 1 mg/l resulted in a reduction to 91.9% in root length compared to the control group in Manó (Fig. 5). This rate was 87.5% for Kecskeméti 549 and 80.3% for Mobil. The values as a percentage of the control group because of the 50 mg/l dose effect was 55.4% for Manó, 59.7% for Kecskeméti 549, and 52.6% for Mobil. This represented an average of 86.6 ± 5.87% (1.00 mg/l) and 55.9 ± 3.57% (50.0 mg/l). The coefficient of determination of Manó is 0.9961, while 0.9710 for Kecskeméti 549 and 0.9908 for Mobil.

Comparative examination of root length in Solanum lycopersicum cultivars (Manó, Kecskeméti 549, and Mobil) exposed to asbestos-contaminated irrigation water. Significant reductions in root length were observed at both 1 mg/l and 50 mg/l concentrations (p ≤ 0.05), with greater inhibition at higher doses. The reduction was most prominent in the 50 mg/l dose, where root length was reduced to 55.4% (Manó), 59.7% (Kecskeméti 549), and 52.6% (Mobil) compared to the control group.

The dose effect of 1 mg/l resulted in a reduction to 95.6% in height of the shoot compared to the control group in Manó (Fig. 6). This value was 95,5% for Kecskeméti 549 and 95,6% for Mobil. The average value as a percentage of the control group because of the 50 mg/l dose effect was 56.0% for Manó, 59.6% for Kecskeméti 549 and 57.8% for Mobil. The average of 1.00 mg/l dose affect is 95.6 ± 0.05% and for 50.0 mg/l is 57.8 ± 1.75%. The coefficient of determination of Manó is 0.9916, 0.9863 for Kecskeméti 549 and 0.9941 for Mobil.

Comparative examination of shoot height in Solanum lycopersicum cultivars (Manó, Kecskeméti 549, and Mobil) exposed to asbestos-contaminated irrigation water. Significant reductions in shoot height were observed at both 1 mg/l and 50 mg/l concentrations (p ≤ 0.05), with greater inhibition at higher doses. The reduction was most prominent in the 50 mg/l dose, where shoot height was reduced to 56.0% (Manó), 59.6% (Kecskeméti 549), and 57.8% (Mobil) compared to the control group.

Discussion

Previous research28has shown that leguminous plants respond to chemical stressors in a dose-dependent manner29,30. Our findings confirm this trend, as Trifolium pratense exhibited significantly lower germination rates at higher doses.

This sensitivity is critical to understanding the ecological implications of chemical exposure, as legumes play a vital role in soil health and fertility due to their ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen31,32. The low germination rates at higher doses indicate that Trifolium pratense has a relatively low chemical tolerance. This may negatively impact its population dynamics and the stability of the surrounding ecosystem.

Many studies have shown that leguminous plants suffer reduced growth and reproductive success when exposed to pollutants33,34. Our findings support this, highlighting the potential risks to their ecological role and agricultural importance. The results are not only striking in the case of Trifolium pratense, but also evident in the two other receptors, which similarly responded to the effects of chemical stressors. Throughout the studies, we observed a significant decrease in germination rates for the other two receptors as well, reinforcing the notion that chemical pollution has widespread effects on various plant species. These findings suggest that the examined chemical substances exert influence not only on specific plants but also on surrounding ecosystems. The diversity of reactions triggered by chemical stressors may yield important insights into maintaining ecological balance and underscores the necessity for further research to achieve a deeper understanding of this phenomenon.

It is crucial to consider that the observed effects may be influenced by the concurrent action of multiple stressors present in the environment. For instance, the leaching of other toxic substances, such as heavy metals or construction-related contaminants, from polluted sites could also contribute to the observed responses. Investigating these interactions and isolating the effects of a single chemical stressor would necessitate further research into the potential cumulative impacts of various pollutants.

Asbestos exposure can disrupt key biological processes in plants. This disruption can lead to abnormal growth patterns, especially in the root and shoot systems35. Additionally, asbestos exposure may impair nutrient uptake by damaging root membranes or inducing oxidative stress, which compromises cellular transport proteins involved in nutrient absorption36,37,38. These cellular disturbances contribute to significant reductions in germination rates, root growth, and shoot height observed in the study, as plants exposed to high asbestos concentrations exhibit stunted development and decreased ability to absorb essential nutrients39,40.

The effects of asbestos on plant growth can also be linked to oxidative stress pathways. When exposed to toxic substances like asbestos, plants often experience an increase in reactive oxygen species, which can damage lipid membranes, proteins, and DNA41,42. This oxidative stress disrupts normal cell functioning, leading to impaired metabolic processes and growth inhibition. Specifically, asbestos exposure may trigger an imbalance between antioxidants and ROS, overwhelming the plant’s defense systems. As a result, plants may exhibit stunted growth, reduced germination rates, and inhibited root elongation, as observed in our study43. These effects align with previous research indicating that oxidative stress is a major factor in plant response to chemical pollutants, as ROS accumulation can interfere with nutrient uptake and cellular respiration44. Therefore, oxidative stress pathways may play a central role in the plant’s inability to tolerate high concentrations of asbestos, contributing to the observed toxic effects on plant development.

Similarly, the significant reduction in root growth at 50 mg/l aligns with other research45showing inhibition of root elongation by comparable phytotoxin concentrations46,47,48. The decrease in shoot height under higher dose conditions is supported by findings49documenting growth inhibition under stressful environmental toxin conditions, involving hormonal imbalances and nutritional uptake disruptions50,51. These dose-dependent inhibitory effects are consistent with broader plant toxicology results52where higher doses impact plant physiological and metabolic processes53,54,55,56,57.

In light of these complexities, it is essential to consider potential confounding factors, such as variations in nutrient availability, water quality, or climatic conditions, which may further complicate the interpretation of dose-response relationships. These factors could independently influence plant health, irrespective of the chemical stressors under investigation. Therefore, it is recommended that future studies either control for these variables or conduct research in a more controlled experimental setup to more accurately isolate the effects of the pollutants.

These findings suggest important implications for environmental policies and strategies to mitigate pollution. The observed phytotoxic effects emphasize the necessity of regulating contaminant levels in agricultural and natural environments to safeguard plant biodiversity and ecosystem stability58,59. Implementing more stringent guidelines on permissible pollutant concentrations in irrigation water and soil can help minimize the adverse impacts of chemical stressors60. Additionally, the results highlight the importance of adopting sustainable agricultural practices, such as phytoremediation and buffer zone management, to alleviate the impact of contaminants on vegetation61,62. These approaches align with broader environmental policies focused on enhancing soil health, maintaining biodiversity, and ensuring food security63.

Such findings highlight the importance of considering dose-response relationships in assessing the risks posed by chemical stressors, particularly in environments where these species are cultivated or naturally occur. Further research is warranted to explore the mechanisms behind this sensitivity and to evaluate the long-term implications for plant communities and agricultural practices. The wider environmental ramifications of these findings also highlight the need for more robust mitigation strategies and policy interventions64,65. Given the demonstrable adverse impacts of chemical contamination, including asbestos pollution, on plant growth and ecosystem resilience, regulatory frameworks should prioritize monitoring and remediation initiatives66. This underscores the imperative of integrating scientific evidence into policy development to mitigate environmental degradation and safeguard biodiversity5. The findings highlight the need to address the real-world challenges for farming in areas with asbestos contamination. The negative impacts on plant growth and germination show the risks to crops grown in polluted soils or irrigated with asbestos-tainted water67. Farmers and land managers in affected regions should explore alternative water sources, soil remediation methods, and more resilient plant species68. This is especially crucial for sustainable agriculture in historically industrial or asbestos-exposed areas14. Further research should focus on practical ways to mitigate these impacts while maintaining agricultural productivity and food safety.

Conclusions

The paper’s results indicate a relationship between the dosage and its effect on seed germination, root length, and shoot height in Trifolium pratense, Medicago sativa, and Solanum lycopersicum. At 1 mg/l concentration, there was minimal impact on germination and growth similar to the control conditions. However, at the higher dosage of 50 mg/l, all parameters showed significant decreases. This significant decrease demonstrates how vulnerable seed germination and seedling development are to increased chemical exposure. The high determination coefficients for germination, root length, and shoot height underline the strong connection between higher dosages leading to negative effects. Despite consistent patterns observed across different cultivars indicates that inherent genetic factors affect resilience. These findings stress the need to understand specific responses of each species or cultivar for better agricultural management aiming at protecting crop yield as well as environmental health. There is also a necessity for further research into identifying both physiological and molecular mechanisms behind these responses which will help enhance crop resilience strategies.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analysed during the current paper are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Maulida, P. T. et al. Environmental assessment of friable asbestos from soil to air using the releasable asbestos sampler (RAS). Toxics 10, 103390toxics10120748 (2022).

Boffetta, P. Classic epidemiology of lung cancer. IASLC Thorac. Oncol. 1-8.e3 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-52357-8.00001-9 (2018).

Mahoney, K. et al. The past, present and future of Asbestos-Related diseases in Australia: what are the data telling Us? Sustainability 15 https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118492 (2023).

Van Orden, D. R. Asbestos, in Environmental Forensics, Elsevier, pp. 19–33. (1964). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012507751-4/50024-0

Li, X. et al. Asbestos-Environment pollution characteristics and Health-Risk assessment in typical Asbestos-Mining area. Toxics 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics11060494 (2023).

Lucci, F. et al. Naturally occurring asbestos (NOA) in granitoid rocks, A case study from Sardinia (Italy). Minerals 8 https://doi.org/10.3390/min8100442 (2018).

Kent, K. et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on rural food security in high income countries: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 19 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063235 (2022).

Krówczyńska, M. et al. Asbestos—Cement roofing identification using remote sensing and convolutional neural networks (CNNs). Remote Sens. 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12030408 (2020).

Xu, L. Metals contamination along the watershed and estuarine areas of Southern Bohai Sea, China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 74 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.06.010 (2013).

Spurny, K. R. On the release of asbestos fibers from weathered and corroded asbestos cement products. Environ. Res. 48 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0013-9351(89)80089-1 (1989).

Musthaq, M. A. et al. The effect of various environmental conditions on the impact damage behaviour of Natural-Fibre-Reinforced composites (NFRCs)—A critical review. Polymers 15 https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15051229 (2023).

Wohlleben, W. et al. Everything falls apart: How solids degrade and release nanomaterials, composite fragments, and microplastics. NanoImpact 34 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.impact.2024.100510

Xie, S. Y. et al. In vitro inhalation bioaccessibility for particle-bound hydrophobic organic chemicals: method development, effects of particle size and hydrophobicity, and risk assessment. Environ. Int. 120 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2018.08.015 (2018).

Peña-Castro, M. et al. A critical review of asbestos concentrations in water and air, according to exposure sources. Heliyon 9 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e15730 (2023).

Favero-Longo, S. E. et al. Lichens on asbestos–cement roofs: bioweathering and biocovering effects. J. Hazard. Mater. 162 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.06.060 (2009).

Zdeb, M. et al. The quality of rainwater collected from roofs and the possibility of its economic use. Resources 9 https://doi.org/10.3390/resources9020012 (2020).

Ervik, T. et al. Mobilization of asbestos fibers by weathering of a corrugated asbestos cement roof. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 18 https://doi.org/10.1080/15459624.2020.1867730 (2021).

Anabtawi, F. et al. Heavy metals in harvested rainwater used for domestic purposes in rural areas: Yatta area, Palestine as a case study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 2683. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052683 (2022).

Trivedi, A. K. et al. Environmental contamination of Chrysotile asbestos and its toxic effects on growth and physiological and biochemical parameters of Lemna gibba. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 47 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00244-004-3161-7 (2004).

Bloise, A. et al. Potentially toxic elements (PTEs) associated with asbestos Chrysotile, tremolite and actinolite in the Calabria region (Italy). Chem. Geol. 558, 119896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2020.119896 (2020).

Trivedi, A. K. & Ahmad, I. Effects of Chrysotile asbestos contaminated soil on crop plants. soil and sediment contamination. Int. J. 20 https://doi.org/10.1080/15320383.2011.609197 (2011).

Warnasooriya, S. N. & Montgomery, B. L. Spatial-specific regulation of root development by phytochromes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Signal. Behav. 6 https://doi.org/10.4161/psb.6.12.18267 (2011).

Benedetti, S. et al. Reactive oxygen species: a double-edged sword for mesothelioma. Oncotarget 6, 16848–16865. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.4253 (2015).

Trivedi, A. K. et al. Environmental contamination of Chrysotile asbestos and its toxic effects on antioxidative system of Lemna gibba. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 52 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00244-006-0056-9 (2007).

Trivedi, A. K. & Ahmad, I. Impact of Chrysotile asbestos contaminated soil on foliar nutrient status of plants. Indian J. Plant. Physiol. 18 https://doi.org/10.1007/s40502-013-0036-9 (2013).

Trivedi, A. K. & Ahmad, I. Genotoxicity of Chrysotile asbestos on Allium cepa L. meristematic root tip cells. Curr. Sci. 105, (2013).

Saleem, K. et al. Chrysotile-Asbestos-Induced damage in Panicum virgatum and Phleum pretense species and its alleviation by Organic-Soil amendment. Sustainability 14 https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710824 (2022).

Wang, Q. R. et al. Responses of legume and non-legume crop species to heavy metals in soils with multiple metal contamination. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part. A. 37 https://doi.org/10.1081/ESE-120003241 (2002).

Pandey, A. K. et al. The Anatomical Basis of Heavy Metal Responses in Legumes and Their Impact on Plant–Rhizosphere Interactions. Plants 11 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11192554

Matamoros, M. A. & Becana, M. Molecular responses of legumes to abiotic stress: post-translational modifications of proteins and redox signaling. J. Exp. Bot. 72 https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erab008 (2021).

Basu, S. et al. Diversity and traits of multiple biotic stressors elicit differential defense responses in legumes. Agriculture 13 (2093). https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13112093 (2023).

Gupta, S. & Das, S. Insight into the Molecular Interaction Between Leguminous Plants and Rhizobia Under Abiotic Stress. In Molecular Plant Abiotic Stress 301–314. Wiley, (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119463665.ch16

Abd-Alla, M. H. et al. Enhancing Rhizobium–Legume symbiosis and reducing nitrogen fertilizer use are potential options for mitigating climate change. Agriculture 13 (2092). https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13112092 (2023).

Gepts, P. et al. Legumes as a Model Plant Family. Genomics for Food and Feed Report of the Cross-Legume Advances through Genomics Conference. Plant Physiology 137 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.105.060871

Łuniewski, S. et al. Plants, microorganisms and their metabolites in supporting asbestos Detoxification—A biological perspective in asbestos treatment. Materials 17 https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17071644 (2024).

Roy, T. et al. Microplastic/nanoplastic toxicity in plants: an imminent concern. Environ. Monit. Assess. 195 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-022-10654-z (2023).

Burachevskaya, M. et al. Accumulation, translocation, and toxicity of arsenic in barley grown in contaminated soil. Plant. Soil. 467 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-021-05067-9 (2021).

Afzal, S. et al. Nanostructure and plant uptake: assessing the ecological footprint and root-to-leaf dynamics. Plant. Nano Biol. 10, 100122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plana.2024.100122 (2024).

Shi, G. L. et al. Accumulation and distribution of arsenic and cadmium in winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) at different developmental stages. Sci. Total Environ. 667 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.02.394 (2019).

Gonneau, C. et al. Framework for assessment and phytoremediation of asbestos-contaminated sites. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 24 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-017-0177-x (2017).

Pietrofesa, R. et al. Asbestos induces oxidative stress and activation of Nrf2 signaling in murine macrophages: chemopreventive role of the synthetic Lignan secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (LGM2605). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17030322 (2016).

Jomova, K. et al. Reactive oxygen species, toxicity, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: chronic diseases and aging. Arch. Toxicol. 97 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-023-03562-9 (2023).

Pizzino, G. et al. Oxidative Stress: Harms and Benefits for Human Health. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity (2017). https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/8416763 (2017).

Jarin, A. S. et al. Drought stress tolerance in rice: physiological and biochemical insights. Int. J. Plant. Biology. 15 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijpb15030051 (2024).

Agudo-Jurado, F. J. et al. Status of phytotoxins isolated from necrotrophic fungi causing diseases on grain legumes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 5116. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24065116 (2023).

Lin, D. & Xing, B. Phytotoxicity of nanoparticles: Inhibition of seed germination and root growth. Environ. Pollut. 150 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2007.01.016 (2007).

Pan, M. & Chu, L. M. Phytotoxicity of veterinary antibiotics to seed germination and root elongation of crops. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 126 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2015.12.027 (2016).

Wang, X. et al. Validation of germination rate and root elongation as indicator to assess phytotoxicity with Cucumis sativus. Chemosphere 44 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0045-6535(00)00520-8 (2001).

Pérez-Labrada, F. et al. Underlying Mechanisms of Action to Improve Plant Growth and Fruit Quality in Crops under Alkaline Stress. In Abiotic Stress in Crop Plants - Ecophysiological Responses and Molecular Approaches. IntechOpen (2024). https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.114335

Raza, A. et al. Plant hormones and neurotransmitter interactions mediate antioxidant defenses under induced oxidative stress in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 13 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.961872 (2022).

Georgieva, M. & Vassileva, V. Stress management in plants: examining provisional and unique Dose-Dependent responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24065105 (2023).

Hafeez, A. et al. Effect of heavy metals on growth, physiological and biochemical responses of plants. In Plants and Their Interaction to Environmental Pollution (pp. 139–159). Elsevier, (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-99978-6.00006-6

dos Santos, T. B. et al. Physiological responses to drought, salinity, and heat stress in plants: A review. Stresses 2 https://doi.org/10.3390/stresses2010009 (2022).

Khan, N. et al. Metabolic and physiological changes induced by plant growth regulators and plant growth promoting rhizobacteria and their impact on drought tolerance in Cicer arietinum L. PLOS ONE. 14 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0213040 (2019).

Gudkov, S. V. et al. Effect of ionizing radiation on physiological and molecular processes in plants. J. Environ. Radioact. 202 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvrad.2019.02.001 (2019).

Hafiz, F. B. et al. Plant nutrition: physiological and metabolic responses, molecular mechanisms and chromatin modifications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23084084 (2022).

Zandalinas, S. I. et al. Plant responses to climate change: metabolic changes under combined abiotic stresses. J. Exp. Bot. 73 https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erac073 (2022).

Durante-Yánez, E. V. et al. Phytoremediation of Soils Contaminated with Heavy Metals from Gold Mining Activities Using Clidemia sericea D. Don. Plants 11, (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11050597

Sorrentino, M. C. et al. Facing metal stress by multiple strategies: morphophysiological responses of cardoon (Cynara cardunculus L.) grown in hydroponics. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-13242-9 (2021).

Alengebawy, A. et al. Heavy metals and pesticides toxicity in agricultural soil and plants: ecological risks and human health implications. Toxics 9, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics9030042 (2021).

Sharma, J. K. et al. Phytoremediation technologies and their mechanism for removal of heavy metal from contaminated soil: an approach for a sustainable environment. Front. Plant Sci. 14 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1076876 (2023).

Hayyat, M. U. et al. Evaluating the phytoremediation potential of Eichhornia crassipes for the removal of cr and Li from synthetic polluted water. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 20 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043512 (2023).

Cozim-Melges, F. et al. Farming practices to enhance biodiversity across biomes: a systematic review. Npj Biodivers. 3 https://doi.org/10.1038/s44185-023-00034-2 (2024).

Nowwar, A. I. et al. Impact of irrigation with wastewater on accumulation of heavy metals in Phaseolus vulgaris L. and its remediation. J. Soil. Sci. Plant. Nutr. 23 https://doi.org/10.1007/s42729-022-01080-8 (2023).

Brunhoferova, H. et al. Removal of 27 micropollutants by selected wetland macrophytes in hydroponic conditions. Chemosphere 281, 130980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.130980 (2021).

Singh, V. et al. Heavy metal contamination in the aquatic ecosystem: toxicity and its remediation using Eco-Friendly approaches. Toxics 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics11020147 (2023).

Popov, M. et al. Effect of arsenic soil contamination on stress response metabolites, 5-Methylcytosine level and CDC25 expression in spinach. Toxics 11, 10–3390. toxics11070568 (2023).

Roy, A. et al. Nanomaterials for remediation of environmental pollutants. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2021 https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/1764647 (2021).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Széchenyi István University (SZE).

“Supported by the ÚNKP-23-3-I New National Excellence Program of the Ministry for Culture and Innovation from the source of the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund.”

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Macher, G.Z., Torma, A. & Beke, D. The impact of asbestos cement pollution in irrigation water on physiological and germination characteristics of Trifolium pratense, Medicago sativa, and Solanum lycopersicum seeds. Sci Rep 15, 16265 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01011-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01011-4