Abstract

The aim of this research was to examine the potential toxic or beneficial impacts of 4,5,6-Trimethoxy-2,3-diphenyl indole on fingerlings of Labeo rohita when administered in water. The study involved four groups of Labeo rohita fish (n = 40) exposed to varying water-borne concentrations (0.00, 32.08, 48.13 and 96.26 mg/L) of 4,5,6-Trimethoxy-2,3-diphenyl indole over a fourteen day period. The fish were maintained under standard living conditions to minimize stress. Histological examination of the brain and gills revealed abnormal tissue structure only in the high-concentration group. The high-concentration group displayed aneurysms, degenerative changes, blood vessel congestion, and structural degeneration in the gills, while the brain exhibited necrosis, pyknosis, hemorrhage, degenerative changes and vacuolization. Levels of glutathione (GSH) decreased in both gills and brain, malondialdehyde (MDA) increased in gills but decreased in the brain, catalase (CAT) decreased in gills but increased in the brain and lipid peroxidase (LPO) significantly increased in both gills and brain only in the high-concentration group. Serum proteins (total proteins, albumin, and globulins) were significantly reduced in the high concentration group. Overall, the study indicated that at a high concentration of 96.26 mg/L through water-borne exposure, 4,5,6-Trimethoxy-2,3-diphenyl indole exhibited toxic effects, while at medium and low concentrations, it demonstrated beneficial effects. The findings suggest that the compound has more beneficial than toxic effects and could be recommended for specific applications to leverage its beneficial properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Indole, a heterocyclic compound, is widely present in nature and has practical applications in medicinal chemistry and drug discovery. Indole has been extensively studied for its role as antioxidants, biomolecules and signaling molecules1,2. Indole has important biological activities as it is an important molecule in eukaryotic systems3,4. It also plays an important role in environmental remediation5,6,7. Its derivatives such as Indomethacin, 5-Hydroxyindole, Indomethacin etc. are being synthesized play important role in diverse pharmacological activities having therapeutic properties. This compound has less toxicity and side effects8.

Indole derivatives are utilized in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and anticancer therapy9,10,11,12. In aquaculture, indole is employed to manage bacterial diseases like vibriosis13. Indole analogues enhance fish growth14. Indole derivatives exhibit outstanding antifouling properties and are employed to hinder the growth of marine algae and bacteria15. Indole finds various industrial applications including agrochemicals16, chemicals17, perfume and fragrance18, dye and paint production19, electronics and solar cells20, cosmetics (Barden, 2010), food industry and biotechnology21.

Indole has various environmental impacts at higher concentrations, including toxicity to aquatic life22, bioaccumulation23, and groundwater contamination24, effects on microorganisms25, food contamination26, and risks to human health27. This compound affects both water chemistry and aquatic organisms, altering nutrient availability, inhibiting plant growth, changing animal behavior, and disrupting the balance of aquatic ecosystems through synergistic effects28,29,30,31. Aquatic species face potential toxicity risks from the prevalent compound indole present in different marine organisms. Brominated indoles and phenol compounds have been shown to interfere with the development of fish embryos22. The environmental implications of using indole derivatives for antifouling purposes have sparked concerns, leading to additional research on the possible toxic impacts on marine ecosystems29.

Indole exposure can happen through different pathways, including dietary intake and metabolic processing in the liver32. Environmental exposure can occur through tobacco carcinogens such as cigarette smoking33. Brominated indole, an indole derivative has been found in water and sediments from the German Bight34. Brominated indole derivatives can cause malformations like spine deformation, low heartbeat, coagulation, incomplete eye development and yolk sac edema22.

Indole derivatives induce hemato-biochemical, hormonal, and histopathological changes35. Considering the pharmacological and industrial applications of our synthesized indoles, it was necessary to assess their toxicity in fish before their practical applications. Our team has successfully synthesized and reported on the 2,3-diphenyl indole heterocycle, including 4,5,6-Trimethoxy-2,3-diphenyl indole and its derivatives. These compounds have demonstrated antioxidant, anticholinesterase and antimicrobial activities36,37,38,39. In our current research, we are investigating the toxicity induced by 4,5,6-Trimethoxy-2,3-diphenyl indole in Labeo rohita fish while also considering its safe limits where it becomes an active agent for its application.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

All the necessary analytical-grade reagents and chemicals were obtained from Arshman Scientific Technical Company in Lahore, Pakistan. The synthesis of 4,5,6-Trimethoxy-2,3-diphenyl indole (TMDPI) was carried out using the Bischler Indole Synthesis method, as previously reported by Rubab et al.40. Infrared spectra (IR) in KBr discs were recorded using a Prestige 21 instrument (Shimadzu, Japan). X-ray diffraction data for TMDPI have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre under publication number CCDC 1,526,270. X-ray diffraction data were collected at the Department of Physics, University of Sargodha, Pakistan.

Synthesis of TMDPI

A mixture of benzoin (39.1 mmol, 8.31 g) and 4,5,6-Trimethoxyaniline (10 mmol, 0.93 g) was heated at 120 °C for 2.5 h. After cooling, glacial acetic acid (25 g, 32 eq, 23.8 mL, 0.417 mol) was added to the brown mixture. Aniline (13 mmol, 1.19 mL, 1 eq) was then added, and the mixture, was heated at 130 °C for 6 h. Upon cooling to room temperature, white precipitates formed. The precipitates were filtered and washed with methanol. The final product, 4,5,6-Trimethoxy-2,3-diphenyl indole, was obtained in a yield of 63%. The product has a retention factor (Rf) of 0.25 in a mixture of n-hexane and ethyl acetate (7:1). The melting point of the product was 219–220 °C36.

The UV log ε value is 2.8, and the λmax is observed at 318 nm. In the IR spectrum (υ´max, KBr), a peak is seen at 3363 cm− 1 corresponding to the N–H bond. The 1H NMR spectrum was recorded at 300 MHz in ppm units, showing a multiplet for two Phenyl groups at 7.23–7.48 (10 H) and a singlet for the N–H proton at 8.12. The H7 proton appears as a singlet at 6.78, and the OMe groups give 3 H singlets at 3.36, 3.72, and 3.87 for C4, C5, and C6, respectively. The LR-EIMS data (m/z in amu units) shows the M+• peak at 359 with 100% abundance36.

Experimental animals

The experimental animals used in this research were Labeo rohita, a common Indian carp often utilized in toxicological studies due to its widespread distribution, sensitivity to pollutants, and easy availability. These animals were sourced from the Government Fish Seed Hatchery in Chashma, Mianwali, Punjab, Pakistan. They were transported to the Department of Zoology, laboratory at the University of Education Lahore, Jauharabad Campus) with careful consideration for their well-being. This included using air-filled and airtight plastic bags, filling the bags with pond water for acclimatization, maintaining optimal temperature, handling them with care, transporting them in a comfortable vehicle, and avoiding overcrowding in the plastic bags.

Experimental setup

The aquariums were setup at proper place of experimentation, washed and cleaned, installed aeration system, filled with useable tap water, monitor water quality parameters and control the variables such as light, temperature and their feeding schedules. The fish were acclimatized for 7 days prior to the experiment, and feed was provided twice daily.

Experimental design

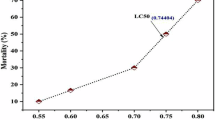

The LC50 of indole was determined by splitting 60 fish into six groups and exposing them to various indole concentrations (0, 300, 600, 900, 1200, and 1500 mg/L) for 96 h. The LC50 was calculated as 962.63 mg/L after applying Probit analysis. This value was then used to establish three sub lethal concentrations, corresponding to one-tenth, one-twentieth, and one-thirtieth of the LC50.

The experimental design was completely randomized and fish were divided into four groups (n = 40; 10 in each group) in aquarium having dimension as 60 × 30 × 30 cm (L x W x H) having 60 L of water capacity. The average weight of each animal was 22.34 gram. Group A was control group and served as baseline for comparisons, Group B was exposed to low concentration of indole (33.08 mg/L), Group C was exposed to medium concentration (48.13 mg/L) of indole and Group D was exposed to high concentration (96.26 mg/L) of indole.

Concentration preparation

A stock solution was prepared by combining 10 mL of water in a falcon tube, with indole, and then using a sonicator (Model: S-DS-6 Stalwart) set to run for 2 h at a frequency of 50 HZ and voltage of 230. This process ensured even distribution in the experimental tanks by creating a uniform solution. The stock solution was then diluted to create four different experimental concentrations (low, medium and high) which were added to the experimental tanks. This same procedure was repeated on every other day for redosing, with half of the tanks water being changed, over a period for 14 days.

Animals feeding protocol

The animals were fed once a day with a diet consisting of 4% of their body weight and 30% protein to ensure their health, despite the challenges caused by indole. The diet given was a commercial diet, one containing standard protein levels in the form of small floating pellets to fulfill their nutritional requirements.

Monitoring

Animals were monitored for the signs of bottom or surface running, stress, gasping, breathing difficulty, illness, restlessness and change in diet intake. Water quality was also regularly checked and maintained standard parameters for producing good survival conditions.

Water quality

The experiment involved monitoring and ensuring the quality of water. The levels of dissolved oxygen were measured at 4.82 ± 0.19 (ppm), pH at 7.17 ± 0.01, temperature at 22.68 ± 0.39 (°C), salinity at 0.4 ± 0.01 (ppt), and total dissolved solids at 450.08 ± 7.57 (mg/L).

Animal sacrifice and dissection protocol

Animals from each group were captured and desensitized in a separate beaker with clove oil (2 to 3 medium drops in 1 L of water) as anesthesia and left for 2 to 3 min to ensure their full sedation41 in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines. They were sacrificed according to the standard ethic guidelines followed by cervical dislocation. The animals were humanly dissected to remove target organs (Brain and gills). Dissection was performed by the research students after proper training using the simple dissection box42. The brain and gills were preserved in 10% formalin solution with normal saline for histological procedure.

Blood collection and processing protocol

Blood was collected from the caudal vein of the fish by using the syringe and stored in eppendorf tube labeled with sample ID, centrifuged for 4000 rpm for 10 min and clear serum was collected from the upper of eppendorf tube and stored in -20 °C for the creatinine, urea, albumin, globulin.

Oxidative stress

Estimation of lipid peroxidation (LPO)

LPO was determined using the methodology described by Jiang et al. (1992)43. The tissue homogenate was mixed with FOX reagent and incubated at 37 °C for thirty minutes. The spectrophotometer measured the samples at a wavelength of 560 nm. The tissue LPO measurement was expressed as mM/g tissue weight.

Estimation of malondialdehyde

Malondialdehyde (MDA) was measured following the method outlined by Ohkawa et al. (1979)44. The tissue homogenate was analyzed using an acetic acid mixture containing sodium dodecyl sulfate and distilled water, heated at 95 °C for one hour. The spectrophotometer measured the readings at a wavelength of 532 nm. The MDA measurement was reported as nm/g tissue.

Estimation of catalase

Catalase estimation was conducted according to the protocol by Aebi45. The tissue homogenate was mixed with phosphate buffer and hydrogen peroxide. The spectrophotometer measured the readings at a wavelength of 240 nm to determine the Units per mL activity of Catalase.

Estimation of glutathione

The tissue homogenate was mixed with trichloroacetic acid, and the supernatant was collected after centrifugation. The supernatant was then treated with DTNP (Ellman’s reagent) and Tris-EDTA buffer. The spectrophotometer measured the readings at a wavelength of 412 nm. The measurement of GSH quantity was reported as µM/g of tissue following the method by Sedlak and Lindsay (1968)46.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS version 20. Means and standard errors were calculated using descriptive statistics, and differences between groups were reported using Tukey’s test.

Results

Our study showed that low and medium concentrations of indole did not have any effect on brain, but a high concentration resulted in damaging effects. In this research, 4,5,6-Trimethoxy-2,3-diphenyl indole was found to induce necrosis, pyknosis, hemorrhage, degenerative changes, and vacuolization in brain tissues. In the gills, aneurysms, degenerative changes, blood vessel congestion, and structural degradation were observed in the similar trend as in brain (Figs. 1 and 2; Table 1).

Brain of fish (400X) Labeo rohita exposed to varying concentrations of 4,5,6-Trimethoxy-2,3-diphenyl indole. (A) Control fish brain displaying normal histoarchitecture. (B) Fish exposed to low and medium concentrations of 4,5,6-Trimethoxy-2,3-diphenyl indole exhibit histoarchitecture similar to normal. (C,D) Moderate complications observed in fish exposed to a high concentration of 4,5,6-Trimethoxy-2,3-diphenyl indole, including necrosis (brown arrow), pyknosis (green arrow), hemorrhage (black arrow), degenerative changes (dark blue arrow), and vacuolization (yellow arrow).

Gills of Labeo rohita (Rohu) (100X) exposed to different concentrations of 4,5,6-Trimethoxy-2,3-diphenyl indole. (A) Control fish gills exhibit normal histoarchitecture. (B) Fish exposed to low and medium concentrations of 4,5,6-Trimethoxy-2,3-diphenyl indole show histoarchitecture similar to normal. (C,D) Moderate complications are observed in fish exposed to a high concentration of 4,5,6-Trimethoxy-2,3-diphenyl indole, including aneurysms (blue arrow), degenerative changes (yellow arrow), congestion of blood vessels (orange arrow), and structural degeneration (green arrow).

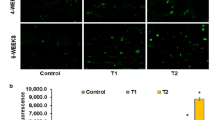

The levels of Glutathione (µM/g) in gills were not significantly different in groups B and C (33.08 and 48.13 mg/L), but there was a significant decrease in group D (96.26 mg/L). Malondialdehyde (nM/g) levels were also not significantly changed in groups B and C, but there was a significant increase in group D. Catalase (Unit/ml) levels were not significantly different in groups B and C, but there was a significant decrease in group D. Lipid Peroxidase (mm/100 g) levels were also not significantly different in groups B and C, but there was an increase in group D. These values were compared to the control group A.

Similarly, the levels of brain Glutathione (µM/g) were not significantly different in groups B and C, but there was a significant decrease in group D. Malondialdehyde (nM/g) and Lipid Peroxidase (mm/100 g) levels were also not significantly different in groups B and C, but there was a significant decrease in group D. Catalase (Unit/mL) levels were significantly increased in group D but remained unchanged in groups B and C. All comparisons were made with the control group (Tables 2 and 3).

In the current study, total proteins (gm/dL) and globulin (gm/dL) levels were unchanged in groups B and C but significantly reduced in group D. Albumin levels remained unchanged in groups B, C, and D compared to the control group A (Table 4).

Discussion

Indole heterocycle has a wide range of applications and benefits47 highlighted its therapeutic effects against arthritis while Zhang et al.48 found that indole-3-propionic acid is beneficial for metabolic diseases. Studies by Ahmad et al.,49, Biswal et al.50, Tomberlin et al.30, Carroll & McEwen51, Williams52, and Amarakoon et al.,53 also support the positive effects of indole. However, indole and its derivatives have been shown to be toxic to various fish species, such as zebrafish22. Heterocycles, including indole are considered aquatic pollutants that pose risks to human and aquatic life54. Studies have demonstrated hemotoxic effects on fish liver cell lines55 and embryotoxic effects of NSO-heterocyclic compounds in zebrafish embryos56. These toxic effects include, cardiotoxicity57, developmental toxicity58 and hepatotoxicity59. Indole has also been linked to oxidative stress, immune imbalances and inflammation. The toxicity of indole varies based on factors such as exposure duration, concentration, and fish species. Other studies have reported both acute and chronic effects of indole on fish, which can be influenced by pH and temperature. High concentrations of indole can lead to complications in fish.

In this study, the synthesis involved using commercially available trimethoxyaniline and benzoin to produce 4,5,6-Trimethoxy-2,3-diphenyl-(1 H)-indole through Bischler indole synthesis. The synthesized indole was characterized using various spectroscopic techniques. UV spectroscopy revealed a λmax value of 318 nm for the indole ring, indicating a bathochromic shift compared to the starting materials. The IR spectrum showed an absorption peak at 3363 cm− 1 attributed to N–H stretching vibrations. The 1 H NMR spectrum displayed a singlet at 8.12 ppm for the N-H proton. Multiplet peaks in the range of 7.23 to 7.48 ppm indicated the presence of 10 protons from the two phenyl rings. The aromatic proton H7 appeared as a singlet at 6.79 ppm. The three -OCH3 substituents were observed at 3.87 ppm, 3.73 ppm, and 3.35 ppm36 (Fig. 3).

The 13C NMR spectrum of TMDPI revealed three triplet carbons at 56.3 ppm, 60.9 ppm, and 61.2 ppm corresponding to three OCH3 groups. A doublet at 90.7 ppm (C7), singlets at 113.5 ppm (C3) and 115.8 ppm (C3a), and doublets in the aromatic region at 126.4 ppm, 127.2 ppm, 127.9 ppm, 128.0 ppm, 128.7 ppm, and 131.3 ppm were observed, indicating phenyl ring carbons (C2, C3, C2’, and C3’). Additionally, signals at 132.9 ppm (C1) and 133.0 ppm (C1’) were detected. Singlets at 133.4 ppm and 136.6 ppm corresponded to C2 and C7a, while peaks at 136.8 ppm (C4), 146.7 ppm (C5), and 151.0 ppm (C6) were also observed. In the LR-EIMS spectrum, a prominent molecular ion peak at m/z 359 [M]+• with 100% relative intensity was detected, indicating a stable molecular structure with minimal fragmentation36.

The structure of 4,5,6-Trimethoxy-2,3-diphenyl-(1 H)-indole (TMDPI) was determined and verified by XRD (CCDC 1526270) as shown in Fig. 4.

In recent studies recent studies, it was found that 4,5,6-Trimethoxy-2,3-diphenyl indole caused necrosis, pyknosis, hemorrhage, degenerative changes and vacuolization in brain tissues. Indole has both positive and negative effects, with the positive effects being more prominent. Yilmaz and Celik60 discovered that Indole-3-butyric acid is neurotoxic following sub-acute and subchronic exposure in rats. Another study indicated that indoxyl sulfate is harmful to the brain and other organs61,62 Additional research has highlighted the neurotoxicity of indole compounds entering the brain63. Furukawa et al.,64 previously reported that Indole-3-acetic acid leads to microencephaly in rat fetuses, with histological changes showing apoptotic cells in the neuroepithelium, neuroepithelium enlargement, and increased cell packing density. Indole has also been linked to induce anxiety, emotional distress and depression like behaviors31,61 reported similar behaviors in rats where gut microbiota-produced indole negatively affected behavior. Indole and its derivatives have demonstrated more protective effects on the brain than toxicity, safeguarding neurotransmitters pathways and their interections with receptors65,66. Moura et al.67 investigated that Indole-3-Acetonitrile interacts with neuroblastoma cells to provide protection. Indole was found to modulate brain function through intricate mechanisms68. The gut microbiota produces indoles in the intestine, which have been shown to enhance brain health61. Some indoles produced in the intestine were found to induce negative emotional behavior in rats31. Indole has also been recognized for its anti-inflammatory properties regulating apoptosis and oxidative stress in brain tissues69. Some of the previous studies reported complications in brain functioning, but histological effects on brain tissues were not reported before our current investigation. In our current research, it was found that the induction of high concentration of our synthesized indole (4,5,6-Trimethoxy-2,3-diphenyl-(1 H)-indole) in fish brains show moderate complications that marked this compound as a nontoxic substance that only becomes toxic at very high concentration.

In our study, low and medium concentrations of indole (4,5,6-Trimethoxy-2,3-diphenyl-(1 H)-indole) dind not affect gills, but at a high concentration, were found to have damaging effects. There were no significant reports of indole affecting the gill structure in fish, but other heterocyclic compounds have been found to be toxic to fish gills. Stoker et al.,70 reported that organic compounds derived from coal can cause damage to fish gills, while Parlak et al.71 found the genotoxic effect of pyridine. Previous studies have not reported indole causing damage to fish gills. In fact, indole has been shown to have protective effects against various pollutants or toxicants, such as indole-3-carbinol, which protected rainbow trout from aflatoxin B172.

Heterocycles also induce oxidative stress in fish affecting the anti-oxidant defense system. Studies have indicated that indole triggers stress response mechanisms, such as quorum quenching enzymes and iron-sulfur clusters, which play a role in oxidative stress induction73. Previous studies have reported that contaminants in our environment induce oxidative stress in fish, leading to tissue damage in organs such as the brain, liver and gills74. In present study the values of Glutathione (µM/g) in gills was non-significant in groups B and C (33.08 and 48.13 mg/L) but significantly decreased in group D (96.26 mg/L). Malondialdehyde (nM/g) was also not significantly altered in B and C but significantly increased in group D. Catalase (Unit/mL) was not significantly altered in B and C but significantly decreased in D. Lipid Peroxidase (mm/100 g) was similarly not significantly changed in B and C but increased in D. The values of group B, C and D were compared to control group A. There are no direct studies showing effects of alterations of Glutathione by indole but exposure to aniline, indole can be considered a more complex derivative of aniline, Sharma and Chadha75 gills. Sharma and Chadha75 also reported similar for malondialdehyde and catalase.

Similarly in present research brain Glutathione (µM/g) was not significantly altered in groups B and C but significantly decreased in group D. Malondialdehyde (nM/g) and Lipid Peroxidase (mm/100 g) were also not altered in in group B and C but significantly decreases in group D. Catalase (Unit/mL) was significantly increased in group D but remains unaltered in groups B and C. All the comparisons were made with control group.

Glutathione and lipid peroxidase showed similar trends in both gills and brain as glutathione decreased and lipid peroxidase decreased significantly in high concentration treated group D. This decrease may be due to inhibition of cystine uptake, a precursor for GSH synthesis that leads to decrease in GSH. Another reason may be inhibition of glutamate–cysteine ligase (GCL), a rate-limiting enzyme in GSH synthesis leads to decrease in GSH. Furthermore generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) may overwhelm the antioxidant capacity of cells, leading to rapid consumption and depletion of GSH. A previous study by Watanabe et al.,76 and Ismail35, found that indoxyl sulfate and indole-3-acetic acid alter glutathione levels and damage hippocampal cell. Ma et al.77 found that indoxacarb, having indole-like benzofused heterocyclic component, exposure led to changes in glutathione metabolism in adult zebrafish livers.

Malondialdehyde and catalase showed contradicted results for both brain and gills. In gills malondialdehyde showed increasing trend may be due to ROS that damage cellular lipids and in brain this showed decreasing trend may be due to aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) activity can metabolize MDA, reducing its accumulation. Catalase showed decreasing trend in gills could be due to the influx of superoxide radicals inhibiting catalase activity but increasing trend in brain an adaptive response to counteract elevated ROS levels. This upregulation enhances the brain’s ability to decompose hydrogen peroxide, thereby mitigating oxidative damage.

In the current study, total proteins (gm/dL), and globulin (gm/dL) were unaltered in group B and C but significantly reduced in group D. Albumin was remained unaltered in groups B, C and D as compared to control group A. The decreased in protein could be due to proteolysis, proteinuria. Furthermore, toxic stress increases cortisol secretion, which promotes protein breakdown to provide amino acids for gluconeogenesis. A previous study by Hervé et al.78 found that indole has a impact on serum albumin in rats, suggesting potential toxic effects. Another study by Bertuzzi et al.79 examined the effects of indole-3-acetic acid on human serum albumin showing that indole competes with L-tryptophan, indicating potenial complications. Bodur and Cokugras80 reported complications in butyrylcholinesterase due to the inhibitory properties of indole. Since no previous study has reported significant changes in fish serum proteins, the current study supports the findings of earlier research.

Conclusion

There are multiple applications of indole and its derivatives. This study explore the toxicity and beneficiality of 4,5,6-Trimethoxy-2,3-diphenyl, an indole derivative having multiple applications in pharmaceuticals, materials science, dyes and pigments, may has toxic effects. The beneficial or toxic effects of this compound have been explored in model organism fish (Labeo rohita). According to investigations of this study no histological abnormalities in the brain and gills at low and medium concentrations were observed (33.08 & 48.13 mg/L) but significant changes were observed at 96.26 mg/L revealed toxicity with histological changes observed in brain such as necrosis, pyknosis, hemorrhage, degenerative changes and vacuolization. In gills histological abnormalities were aneurysms, degenerative changes, congestion of blood vessels and structural degeneration. Similarly, no alterations were seen in antioxidant indicators (GSH, MDA, LPO and CAT) at low and medium concentrations but at 96.26 mg/L significant alterations were observed. Proteins (total proteins and globulin) were altered in similar trend but albumin (gm/dL) remained non-significant in all experimental groups. Generally, indole has anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant and anti-cancer properties, making it safer for use in pharmaceutical products and other common industrial applications. Similarly, 4,5,6-Trimethoxy-2,3-diphenyl also has more beneficial effects as compared to its toxicity may recommended for practical applications. Further it needs to be tested on different species with more precise doses.

Data availability

All the data of this study is contained in this manuscript. More data related to this study can be accessed upon a reasonable request to the corresponding authors.

References

de Sa Alves, F. R. & Barreiro, E. J. Manssour Fraga, C. A. From nature to drug discovery: the Indole scaffold as a ‘privileged structure’. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 9 (7), 782–793 (2009).

Chadha, N. & Silakari, O. Indoles as therapeutics of interest in medicinal chemistry: Bird’s eye view. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 134, 159–184 (2017).

Singh, T. P. & Singh, O. M. Recent progress in biological activities of Indole and Indole alkaloids. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 18 (1), 9–25 (2018).

Mahmoud, E., Hayallah, A. M., Kovacic, S., Abdelhamid, D. & Abdel-Aziz, M. Recent progress in biologically active Indole hybrids: a mini review. Pharmacol. Rep. 74 (4), 570–582 (2022).

Ma, Q., Zhang, X. & Qu, Y. Biodegradation and biotransformation of Indole: advances and perspectives. Front. Microbiol. 9, 2625 (2018).

Pandey, R., Swamy, K. V. & Khetmalas, M. B. Indole: a novel signaling molecule and its applications. (2013).

Lee, J. H. & Lee, J. Indole as an intercellular signal in microbial communities. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 34 (4), 426–444 (2010).

Kumari, A. & Singh, R. K. Medicinal chemistry of Indole derivatives: current to future therapeutic prospectives. Bioorg. Chem. 89, 103021 (2019).

Bariwal, J., Voskressensky, L. G. & Van der Eycken, E. V. Recent advances in spirocyclization of Indole derivatives. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47 (11), 3831–3848 (2018).

Devi, N., Kaur, K., Biharee, A. & Jaitak, V. Recent development in Indole derivatives as anticancer agent: a mechanistic approach. Anti-cancer Agents Med. Chem. 21 (14), 1802–1824 (2021).

Kumar, D. et al. Medicinal perspective of Indole derivatives: recent developments and structure-activity relationship studies. Curr. Drug Targets. 21 (9), 864–891 (2020).

Sachdeva, H., Mathur, J. & Guleria, A. Indole derivatives as potential anticancer agents: a review. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 65 (3), 4900–4907 (2020).

Defoirdt, T. Indole signaling, a promising target to control vibriosis in aquaculture. Aquaculture 574, 739692 (2023).

Pang, A. et al. Effects of indole-3-butyric acid supplementation in diets containing high soybean meal on growth, intestinal inflammation, and intestinal flora of pearl gentian grouper (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus × Epinephelus lanceolatus). Aquaculture International. 1–19 (2024).

Feng, K., Ni, C., Yu, L., Zhou, W. & Li, X. Synthesis and antifouling evaluation of Indole derivatives. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 182, 109423 (2019).

Rani, M., Utreja, D. & Sharma, S. Role of Indole derivatives in agrochemistry: synthesis and future insights. Curr. Org. Chem. 26 (7), 651–678 (2022).

Inman, M. & Moody, C. J. Indole synthesis—something old, something new. Chem. Sci. 4 (1), 29–41 (2013).

Mindt, M. et al. Production of Indole by Corynebacterium glutamicum microbial cell factories for flavor and fragrance applications. Microb. Cell. Fact. 21 (1), 45 (2022).

Ni, C., Chen, G., Li, X., Zhao, H. & Yu, L. Synthesis and application of Indole esters derivatives containing acrylamide group as antifouling agents. Chem. Phys. Lett. 781, 138994 (2021).

Nitha, P. R., Soman, S. & John, J. Indole fused heterocycles as sensitizers in dye-sensitized solar cells: an overview. Mater. Adv. 2 (19), 6136–6168 (2021).

Ferrer, L., Mindt, M., Wendisch, V. F. & Cankar, K. Indoles and the advances in their biotechnological production for industrial applications. Syst. Microbiol. Biomanufacturing. 4 (2), 511–527 (2024).

Kammann, U., Vobach, M. & Wosniok, W. Toxic effects of brominated Indoles and phenols on zebrafish embryos. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 51, 97–102 (2006).

Öztürk, A. & Abdullah, M. I. Toxicological effect of Indole and its Azo dye derivatives on some microorganisms under aerobic conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 358 (1–3), 137–142 (2006).

Hama, J. R. et al. Indole and Quinolizidine alkaloids from blue lupin leach to agricultural drainage water. Sci. Total Environ. 834, 155283 (2022).

Wani, P. A., Zaidi, A., Khan, A. A. & Khan, M. S. Effect of phorate on phosphate solubilization and Indole acetic acid releasing potentials of rhizospheric microorganisms. Annals Plant. Prot. Sci. 13 (1), 139–144 (2005).

Wang, C., Defoirdt, T. & Rajkovic, A. The impact of Indole and mucin on sporulation, biofilm formation, and enterotoxin production in foodborne Clostridium perfringens. J. Appl. Microbiol. 135 (4), lxae083 (2024).

Almagro, L., Fernández-Pérez, F. & Pedreño, M. A. Indole alkaloids from Catharanthus roseus: bioproduction and their effect on human health. Molecules 20 (2), 2973–3000 (2015).

Ashida, H., Hashimoto, T., Tsuji, S., Kanazawa, K. & Danno, G. I. Synergistic effects of food colors on the toxicity of 3-amino-1,4-dimethyl-5H-pyrido[4,3-b]indole (Trp-P-1) in primary cultured rat hepatocytes. J. Nutri. Sci. Vitaminol. 46 (3), 130–136 (2000).

Yang, C., Sun, W., Liu, S. & Xia, C. Comparative effects of Indole derivatives as antifouling agents on the growth of two marine diatom species. Chem. Ecol. 31 (4), 299–307 (2015).

Tomberlin, J. K. et al. Indole: an evolutionarily conserved influencer of behavior across kingdoms. BioEssays 39 (2), 1600203 (2017).

Jaglin, M. et al. Indole, a signaling molecule produced by the gut microbiota, negatively impacts emotional behaviors in rats. Front. NeuroSci. 12, 216 (2018).

Hubbard, T. D., Murray, I. A. & Perdew, G. H. Indole and Tryptophan metabolism: endogenous and dietary routes to ah receptor activation. Drug Metab. Dispos. 43 (10), 1522–1535 (2015).

Nauwelaërs, G., Bellamri, M., Fessard, V., Turesky, R. J. & Langouët, S. DNA adducts of the tobacco carcinogens 2-amino-9H-pyrido[2,3-b]indole and 4-aminobiphenyl are formed at environmental exposure levels and persist in human hepatocytes. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 26 (9), 1367–1377 (2013).

Reineke, N. et al. Brominated Indoles and phenols in marine sediment and water extracts from the North and Baltic Seas—concentrations and effects. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 51, 186–196 (2006).

Ismail, H. T. H. Assessment toxic effects of exposure to 3-indoleacetic acid via hemato-biochemical, hormonal, and histopathological screening in rats. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29 (60), 90703–90718 (2022).

Nisar, B. et al. N. An efficient protocol for the synthesis of highly sensitive Indole Imines utilizing green chemistry: optimization of reaction conditions. Mol. Diversity. 22, 709–722 (2018).

Gondal, H. Y. et al. Synthesis, characterization, and in vitro anti-cholinesterase screening of novel Indole amines. RSC Adv. 13 (2), 1203–1215 (2023).

Rubab, S. L. et al. Synthesis, crystal structure, DFT calculations, Hirshfeld surface analysis and in Silico drug-target profiling of (R)-2-(2-(1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)propanamido)benzoic acid Methyl ester. Molecules 28 (11), 4375 (2023).

Raza, A. R. et al. Evaluation of antimicrobial, anticholinesterase potential of Indole derivatives and unexpectedly synthesized novel benzodiazine: characterization, DFT and Hirshfeld charge analysis. Molecules 28 (13), 5024 (2023).

Rubab, S. L. et al. Synthesis and antioxidant screening of novel Indole amines. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 1–12 (2022).

Taylor, P. W. & Roberts, S. D. Clove oil: an alternative anaesthetic for aquaculture. North. Am. J. Aquaculture. 61 (2), 150–155 (1999).

Gupta, T. & Mullins, M. C. Dissection of organs from the adult zebrafish. JoVE J. Visualized Experiments (37), e1717 (2010).

Jiang, Z. Y., Hunt, J. V. & Wolff, S. P. Ferrous ion oxidation in the presence of Xylenol orange for detection of lipid hydroperoxide in low density lipoprotein. Anal. Biochem. 202 (2), 384–389 (1992).

Ohkawa, H., Ohishi, N. & Yagi, K. Assay for lipid peroxidase in animal tissue by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal. Biochem. 95, 351–358 (1979).

Aebi, H. Catalases. In: (ed Bergmeyer, H. U.) Methods of Enzymatic Analysis. Chemic Academic Press Inc., Verlag Chemie International: 673–684 (1974).

Sedlak, J. & Lindsay, R. H. Estimation of total, protein-bound, and nonprotein sulfhydryl groups in tissue with Ellman’s reagent. Anal. Biochem. 25, 192–205 (1968).

Hasan, H., Ismail, H., El-Orfali, Y. & Khawaja, G. Therapeutic benefits of indole-3-carbinol in adjuvant-induced arthritis and its protective effect against methotrexate induced-hepatic toxicity. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 18, 1–12 (2018).

Zhang, B. et al. The mechanism underlying the influence of indole-3-propionic acid: a relevance to metabolic disorders. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 841703 (2022).

Ahmad, A., Sakr, W. A. & Wahidur, K. M. Anticancer properties of Indole compounds: mechanism of apoptosis induction and role in chemotherapy. Curr. Drug Targets. 11 (6), 652–666 (2010).

Biswal, S., Sahoo, U., Sethy, S., Kumar, H. K. S. & Banerjee, M. Indole: the molecule of diverse biological activities. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 5 (1), 1–6 (2012).

Carroll, J. & McEwen, B. The health benefits of glucosinolates, indole-3-carbinol and Sulforaphane from broccoli: a brief report. J. Australian Traditional-Medicine Soc. 25 (3), 142–144 (2019).

Williams, D. E. Indoles derived from glucobrassicin: cancer chemoprevention by indole-3-carbinol and 3,3′-diindolylmethane. Front. Nutr. 8, 734334 (2021).

Amarakoon, D., Lee, W. J., Tamia, G. & Lee, S. H. Indole-3-carbinol: occurrence, health-beneficial properties, and cellular/molecular mechanisms. Annual Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 14 (1), 347–366 (2023).

Brinkmann, M. et al. Genotoxicity of heterocyclic PAHs in the micronucleus assay with the fish liver cell line RTL-W1. PLoS One. 9 (1), e85692 (2014).

Ghosh, P. & Mukherji, S. Fate, detection technologies and toxicity of heterocyclic PAHs in the aquatic and soil environments. Sci. Total Environ. 892, 164499 (2023).

Peddinghaus, S. et al. Quantitative assessment of the embryotoxic potential of NSO-heterocyclic compounds using zebrafish (Danio rerio). Reprod. Toxicol. 33 (2), 224–232 (2012).

Nayak, S. R. R. et al. Indole-3-acetic acid induced cardiogenesis impairment in in-vivo zebrafish via oxidative stress and downregulation of cardiac morphogenic factors. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 104479 (2024).

Walton, K., Gantar, M., Gibbs, P. D., Schmale, M. C. & Berry, J. P. Indole alkaloids from Fischerella inhibit vertebrate development in the zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryo model. Toxins 6 (12), 3568–3581 (2014).

Oganesian, A. et al. Potency of dietary indole-3-carbinol as a promoter of aflatoxin B1-initiated hepatocarcinogenesis: results from a 9000 animal tumor study. Carcinogenesis 20 (3), 453–458 (1999).

Yilmaz, Z. & Celik, I. Neurotoxic and immunotoxic effects of indole-3-butyric acid on rats at subacute and subchronic exposure. Neurotoxicology 30 (3), 382–385 (2009).

Tennoune, N., Andriamihaja, M. & Blachier, F. Production of Indole and Indole-related compounds by the intestinal microbiota and consequences for the host: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Microorganisms 10 (5), 930 (2022).

Štolc, S. Indole derivatives as neuroprotectants. Life Sci. 65 (18–19), 1943–1950 (1999).

Collins, M. A., Neafsey, E. J., Matsubara, K., Cobuzzi, R. J. Jr & Rollema, H. Indole-N-methylated β-carbolinium ions as potential brain-bioactivated neurotoxins. Brain Res. 570 (1–2), 154–160 (1992).

Furukawa, S., Abe, M., Usuda, K. & Ogawa, I. Indole-3-acetic acid induces microencephaly in rat fetuses. Toxicol. Pathol. 32 (6), 659–667 (2004).

Hornedo-Ortega, R., Da Costa, G., Cerezo, A. B., Troncoso, A. M. & Richard, T. Garcia-Parrilla, M. C. In vitro effects of serotonin, melatonin, and other related Indole compounds on amyloid-β kinetics and neuroprotection. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 62 (3), 1700383 (2018).

Hubková, B. et al. Tryptophan: its metabolism along the kynurenine, serotonin, and Indole pathway in malignant melanoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (16), 9160 (2022).

Moura, C., Correia, A. S. & Vale, N. Exploring the interaction of indole-3-acetonitrile with neuroblastoma cells: Understanding the connection with the serotonin and dopamine pathways. Biomedicines 11 (12), 3325 (2023).

Pappolla, M. A. et al. Indoles as essential mediators in the gut-brain axis. Their role in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 156, 105403 (2021).

El-Naga, R. N., Ahmed, H. I. & Al Haleem, E. N. Effects of indole-3-carbinol on clonidine-induced neurotoxicity in rats: impact on oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis and monoamine levels. Neurotoxicology 44, 48–57 (2014).

Stoker, P. W., Larsen, J. R., Booth, G. M. & Lee, M. L. Pathology of gill and liver tissues from two genera of fishes exposed to two coal-derived materials. J. Fish Biol. 27 (1), 31–46 (1985).

Parlak, V. et al. Hematotoxic, oxidative and genotoxic damage in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) after exposure to 3-benzoylpyridine. Toxicol. Mech. Methods. 32 (7), 501–509 (2022).

Goeger, D. E., Shelton, D. W., Hendricks, J. D. & Bailey, G. S. Mechanisms of anti-carcinogenesis by indole-3-carbinol: effect on the distribution and metabolism of aflatoxin B1 in rainbow trout. Carcinogenesis 7 (12), 2025–2031 (1986).

Wang, Y., Li, H., Cui, X. & Zhang, X. H. A novel stress response mechanism, triggered by Indole, involved in quorum quenching enzyme MomL and iron-sulfur cluster in Muricauda olearia Th120. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 4252 (2017).

Lushchak, V. I. Contaminant-induced oxidative stress in fish: a mechanistic approach. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 42, 711–747 (2016).

Sharma, G. & Chadha, P. Toxic effects of aniline in liver, gills and kidney of freshwater fish Channa punctatus after acute exposure. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C: Toxicol. Pharmacol. 281, 109916 (2024).

Watanabe, K. et al. Effect of uremic toxins on hippocampal cell damage: analysis in vitro and in rat model of chronic kidney disease. Heliyon 7(2) (2021).

Ma, L. et al. Metabolomics and mass spectrometry imaging reveal the chronic toxicity of Indoxacarb to adult zebrafish (Danio rerio) livers. J. Hazard. Mater. 453, 131304 (2023).

Hervé, F., Grigorova, A. M., Rajkowski, K. & Cittanova, N. Differences in the binding of thyroid hormones and Indoles by rat α1-fetoprotein and serum albumin. Eur. J. Biochem. 122 (3), 609–612 (1982).

Bertuzzi, A. et al. Binding of indole-3-acetic acid to human serum albumin and competition with L-tryptophan. Clin. Chim. Acta. 265 (2), 183–192 (1997).

Bodur, E. & Cokugras, A. N. The effects of indole-3-acetic acid on human and horse serum butyrylcholinesterase. Chemico-Biol. Interact. 157, 375–378 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) Saudi Arabia.

Funding

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L.R.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Methodology, Writing - original draft., Project administration, Investigation,; M.A.: Writing - original draft., Methodology, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Visualization, Writing-review & Editing; H.A.K.: Writing - review & editing, Data Curation, Visualization,; S.A.A. Validation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.; A.I. Visualization, Funding acquisition, Writing - review & editing,.; M.E. A. Z: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical committee approval and statement

This is certified that animals were treated in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines and the experimental protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee on Animal Experimentation at the Department of Zoology, UE (Jauharabad campus) under Approval No UE/JBD/ZOOL/2023/15, dated 02/12/2023 and is in accordance with the guidelines of OECD.

Declaration of AI use

We have not used AI-assisted technologies in creating this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rubab, S.L., Asad, M., Khan, H.A. et al. Exploring the toxicological and beneficial effects of 4,5,6-Trimethoxy-2,3-diphenyl indole on Labeo rohita fingerlings. Sci Rep 15, 16206 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01099-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01099-8