Abstract

Fracture surgery for metastatic femur is frequently performed in older adults. In contrast to impending fracture (IF), complete pathological fracture (CF) renders patients bedridden during the preoperative period, which might affect the postoperative recovery of ambulation. Thus, we aimed to investigate the clinical significance of the recovery in older adults after fracture surgery for femoral metastasis, and predictors for recovery after CF. This multicenter retrospective study enrolled 146 adults aged ≥55 years undergoing surgery. A total of 78.1% (114/146) patients showed recovery; no association was observed between the presence of postoperative weight-bearing restriction and recovery (p = 0.50). The rate of chemotherapeutic intervention was higher in patients who had recovered compared to the others (52/114 vs. 8/32, p = 0.03). Non-recovery of ambulation was an independent poor prognostic factor for one-year suvival (hazard ratio, 1.85; 95% confidence interval, 1.06–3.22; p < 0.01). Subgroup analyses showed shorter preoperative waiting periods in the recovered patients than in the others (5.6 ± 0.6 vs. 7.9 ± 1.1; p = 0.03) among CF cases. Recovery of ambulation was a prognostic factor and was associated with postoperative chemotherapy. Shorter preoperative waiting time was associated with the recovery in patients with CF. Prompt surgical intervention should be considered when older adults develop CF due to femoral metastasis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Preventing metastasis is challenging owing to its multifactorial process1,2. After the diagnosis of bone metastasis, quality of life becomes important for the care of patients3. Fracture surgery for femoral metastasis is frequently performed in older adults since old age is a risk factor for bone metastasis in common cancers4,5,6,7,8,9. When comparing different fracture types at the femur, impending fracture (IF) is associated with better recovery of ambulation than complete pathological fracture (CF)10,11,12. Moreover, while patients with IF can mobilize preoperatively using a walking aid or chair, those with CF are rendered bedridden during the preoperative period. This poses a substantial risk since physical inactivity during hospitalization can cause the loss of muscle mass, especially in older adults13, reducing their ability to perform activities of daily living postoperatively14. Prophylactic interventions have been suggested15 among patients with CF, comprising 40–60% of the cases of fracture surgery for metastatic femur10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17.

The clinical guideline of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons recommends prompt surgery in adults aged ≥55 years suffering a naïve fracture at the proximal femur18,19 within 24–48 h after hospitalization18,19,20,21. This short waiting time for femoral fracture surgery improves the ability to perform postoperative activities of daily living in older adults22,23.

Although previous studies have shown the clinical implications of recovery of ambulation after surgery for femoral metastasis on patient benefits12, the impact in older adults remains to be fully elucidated. The recovery of ambulation in older adults after fracture surgery is related to the subsequent activities of daily living. Additionally, when considering chemotherapeutic interventions for patients with advanced-stage cancer, the ambulation status undoubtedly contributes to decision-making for further treatment12,24. No previous report has focused on the factors associated with recovery of ambulation in older adults with CF. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to (1) assess the significance of ambulation recovery in older adults after surgery for femoral metastasis and (2) investigate the preoperative predictors for recovery of ambulation in the subgroup of patients with CF. We hypothesized that the preoperative waiting time in older adults with CF might affect postoperative ambulation.

Methods

Study design and participants

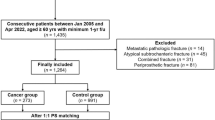

In this multicenter retrospective cohort study, we collected the medical records of 170 adults aged ≥ 55 years who were diagnosed with malignant tumors and underwent femoral fracture surgery between January 2008 and January 2023. The fracture sites in the reviewed patients were investigated preoperatively using magnetic resonance imaging, positron emission tomography-computed tomography, and/or computed tomography methods other than plain radiography.

The fracture was defined by the imaging modality and/or pathological evaluation and 146 patients were enrolled in the analysis. The exclusion criteria were as follows:

-

1.

patients with no tumor mass on the fracture site per imaging, which was not considered a pathological fracture.

-

2.

patients who underwent revision procedures or surgeries for multiple bone lesions.

-

3.

Patients diagnosed with cognitive impairments.

The study was approved by the local ethics committees of Hokkaido University Hospital (022–0036) and the other participating hospitals. Informed consent was obtained by the opt-out method. No data related to these participants were included in the analysis. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of human ethics set forth by the Declaration of Helsinki.

Variables and outcomes

The medical records of the patients included in the study were collected, and the demographic and clinicopathologic characteristics including primary cancer were reviewed. IF was defined as having a Mirels’ score of ≥ 825; the Katagiri–New score (A: 0–3, B: 4–6, and C: 7–10) was assessed based on six prognostic factors: primary tumor, visceral or cerebral metastasis, abnormal laboratory data, poor performance status based on the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG-PS) (0–1, 2–4), previous chemotherapy, and multiple skeletal metastases26. The preoperative waiting time was defined as the time interval between the date of admission and the surgical intervention, and the surgical procedures comprised the perioperative information. Internal fixation is a surgical procedure to insert implants, such as nails, inside the body to fixate and stabilize fractured bone. Endoprosthesis involves replacing fractured joints or bone proximal or distal femur with an artificial prosthesis.

The postoperative protocols were according to clinical practice guidelines in Japan, recommending early postoperative rehabilitation for proximal femoral fracture27. The postoperative weight-bearing restriction was decided by surgeons on a case-by-case basis. Evaluation of postoperative ambulation was conducted following previously reported methods12,28, with recovery of ambulation defined as the ability to walk independently or with assistive devices within 60 days of hospitalization postoperatively. In contrast, patients who required a wheelchair or were bedridden were considered wheelchair-bound or bedridden, respectively. Postoperative chemotherapy was initiated after the physicians validated the stable physical status of the patients.

The primary outcome of this study was the 1-year mortality rate after surgery, whereas the secondary outcome was the rate of postoperative chemotherapeutic intervention in the enrolled patients. Chemotherapy is classified into three groups, cytotoxic drugs, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), and molecular targeted therapy. The duration of chemotherapy was assessed. In CF cases, the association between clinicopathological characteristics and the recovery of ambulation was evaluated.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using JMP Pro version 14 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA), with statistical significance set at a p < 0.05. Categorical and continuous data are presented as frequencies with percentages and means with standard errors, respectively. Categorical variables were evaluated using the chi-squared test for two or more groups, while continuous variables were analyzed using an independent t-test.

Overall survival was visualized using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences were investigated using the log-rank test. Hazard ratios (HR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using Cox regression29. Since age, sex, and body mass index (BMI) are known factors for cancer and fracture, these variables were included in the statistical models. The Cox proportional hazards model, adjusted for age, sex, and BMI, was used to investigate the HR of 1-year mortality for a high-risk Katagiri–New score (C: 7–10), along with non-recovery of ambulation.

Results

Perioperative characteristics

As shown in Table 1, the mean (standard error) age of the patients in this study was 69.6 ± 0.7 years, and 66/146 (45.2%) patients were females. The most frequent primary cancer sites in the enrolled patients were lung, breast, and renal cell carcinoma, and the rate of radiation therapy conducted at the surgical site was 49.3% (69/146). Among the surgical procedures, the rate of endoprosthesis was 18.2% (12/66) in CF cases, and 35.0% (28/80) in IF cases (p = 0.02).

There was no significant difference in postoperative weight-bearing restriction across the facilities (19/124 vs. 7/22, p = 0.06). Postoperative weight-bearing restriction was higher in CF than in IF cases (17/66 vs. 9/80, p = 0.02). The postoperative weight-bearing restriction was higher in patients who underwent internal fixation than those who underwent endoprosthesis (23/106 vs. 3/40, p = 0.04).

Recovery of ambulation

A total of 78.1% (114/146) of patients recovered ambulation. There was no association between the presence of postoperative restriction and the recovery; 16.7% (19/114) of patients with the recovery had the postoperative restriction; 21.9% (7/32) of patients with non-recovery of ambulation had postoperative restriction (p = 0.50). The rate of home discharge was higher in patients with recovery of ambulation than in those with non-recovery (83/114 vs. 5/32, p < 0.01). The rate of loss to one-year follow-up in this study was 6.2% (9/146).

Postoperative chemotherapeutic interventions

The postoperative rate of chemotherapeutic interventions was higher in patients with recovery of ambulation than in those with non-recovery of ambulation (52/114 vs. 8/32, p = 0.03). In patients with the recovery of ambulation, chemotherapeutic intervention after partial or full weight bearing and ambulation with aids was administered. In 60 patients with chemotherapy, 42 patients were prescribed cytotoxic drugs, 7 with ICIs, and 14 patients underwent targeted therapy. Four patients required more than just mono-type therapy. From the perspective of the duration of chemotherapy, 20 patients required intervention for 3 months or less. Eleven patients required it for 4 to 12 months; 29 patients required intervention for more than 12 months. In terms of the regimen of chemotherapy, 32.7% (17/52) and 37.5% (3/8) of patients with recovery of ambulation and non-recovery of ambulation, respectively, were administered ICIs or targeted therapy (p = 0.79).

Postoperative survival

The log-rank test showed that recovery of ambulation was associated with one-year survival (p < 0.01) (Fig. 1). Moreover, the Cox proportional hazards model demonstrated that non-recovery of ambulation (HR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.06–3.22) and a high-risk Katagiri–New score (HR, 5.1; 95% CI, 2.3–11.4) were independent poor prognostic factors (Table 2). One-year survival rates were higher in the patients with the recovery of ambulation than the others (56.1% (60/107) vs. 22.6% (7/31), p < 0.01); two-year survival ratios were higher among recovered patients (31.7% (32/101) vs. 13.3% (4/30), p = 0.04). Three-year survival ratio in the recovered patients was 22.4% (21/94) and that in others was 10.0% (3/30, p = 0.14).

Subgroup analysis of the patients with CF showed significantly shorter preoperative waiting periods among patients with recovery of ambulation than in those with non-recovery of ambulation (5.6 ± 0.6 vs. 7.9 ± 1.1; p = 0.03) (Table 3). Furthermore, premorbid ECOG-PS scores and surgical procedures were associated with the recovery of ambulation. In both groups, the most common primary tumors were those of the lungs, breasts, and kidneys. Multivariate analyses adjusted by age, sex, BMI, and Katagiri-New Score showed that surgical procedures were a significant factor for the recovery of ambulation (p = 0.02); no associations were observed in premorbid ECOG-PS (p = 0.19) or the preoperative waiting time (p = 0.27).

Discussion

This study found recovery of postoperative ambulation as an independent prognostic factor in older adults undergoing fracture surgery for femoral metastases. Patients with recovery of ambulation had higher rates of postoperative chemotherapy. Subgroup analysis of older adults with CF showed that the preoperative waiting time was significantly associated with recovery of ambulation. Therefore, to promote better clinical outcomes in older adults with CF of the femur, prompt surgical intervention should be considered once femoral fracture due to metastasis is diagnosed. Perioperative rehabilitation to prevent disuse syndrome and practice early post-operative mobilization needs to be discussed by multidisciplinary care teams.

Our results showed that 78.1% of older adults with fracture surgery at the femur recovered ambulation; a recent study reported 67.6% pathological fracture at the femur12. This recovery would improve the ability to perform postoperative activities of daily living in older adults22,23 and render them eligible for further therapeutic interventions. When considering chemotherapeutic interventions for patients with advanced-stage cancer, the ambulation status undoubtedly contributes to the decision-making of further treatment12,24.

Notably, the preoperative waiting time in patients who had surgery for metastatic femur with IF or CF is not associated with the recovery of ambulation12; however, our study was distinct in that it focused on the association between the waiting time and recovery of ambulation in older adults with CF. In clinical practice, older adults with IF of the femur can ambulate with non-weight bearing during preoperative periods, whereas those with CF are likely bedridden. However, acute inactivity during hospitalization poses a potent threat to muscle tissue and functional capacity13,30, and physical inactivity during hospitalization contributes to a reduction in the ability to perform activities of daily living, especially in older adults14,31. Our results corroborated these previous findings. Furthermore, in line with our results, previous studies have reported the association of premorbid ECOG-PS scores and surgical procedures with recovery of ambulation in patients with femoral metastases12. There might be potential collinearity in these factors from a clinical perspective. Patients with CF with poor PS may need thorough preoperative evaluation, leading to longer preoperative periods, and less invasive surgical procedures; surgical time was shorter for internal fixation than endoprosthesis7.

Multivariate analyses in patients with CF showed that the surgical procedure was the prognostic factor for the recovery of ambulation. Endoprosthesis is often considered when replacing fractured bone located near the joints while internal fixation is widely used for proximal, diaphyseal, and distal fractures at the femur. Our results suggested that endoprosthesis can be considered actively for patients with ECOG-PS 0–2 with a complete pathological fracture at the proximal or distal femur, aligning with an existing guideline32.

Emergent surgery has been proposed for osteoporotic femoral fractures in older adults21. While performing surgery within 48 h of hospital arrival is desirable for these fractures21, patients with complete pathological fractures require a more thorough preoperative evaluation as they are more likely to have preoperative comorbidities33. If preoperative examinations reveal venous thromboembolism (VTE), lung infection, or acute heart failure, prompt surgery may not be possible. Perioperative complications, such VTE, blood transfusion, and unplanned return to the operating room should be considered34. Surgery time, incision length, and high C-reactive protein are associated with postoperative infection rates35. Our study suggested the association of the preoperative waiting time with the recovery of ambulation. This supports the evidence for prompt surgery for pathological fractures. Prospective studies of prompt surgical interventions for patients with CF are warranted. Criteria could be set as follows: patients with ECOG PS 0–2, fracture at the proximal femur, and no cognitive impairment. In this setting, endoprosthesis might be preferred and is less likely to have postoperative weight-bearing restriction. The importance of preoperative waiting time can be assessed by postoperative survival and quality of life.

The Katagiri–New score is based on six prognostic factors: primary tumor, visceral or cerebral metastasis, abnormal laboratory data, poor PS, previous chemotherapy, and multiple skeletal metastases26. While this score is considered to reflect the prognosis of patients with bone metastasis, other comorbidities, such as heart failure, diabetes, or dementia, may be associated with prognosis in patients with stage 4 cancer. Housing environment or social support are important factors in considering treatment strategies, including chemotherapy.

Metastasis prevention is challenging owing to its multifactorial processes1,2. After the occurrence of bone metastasis, quality of life is important when providing care to these patients3. In fact, prophylactic interventions15 should be considered for preventing fractures; patients with CF comprise 40–60% of the cases of fracture surgery10,11,16,17. For these patients, prompt surgical intervention can yield functional and survival outcomes.

The limitations should be considered when interpreting our results. First, due to the retrospective nature of the study, a recall or selection bias may exist. We did not adjust for potential confounders, such as type of cancer, surgical procedures, preoperative performance status, and patient characteristics including age, sex, and comorbidities. Second, recovery of ambulation was observed within 60 days of hospitalization after surgery, and this evaluation was insufficient in cases transferred to other institutes. It was not strictly consistent with standardized tools, such as the Parker Mobility Score. Third, surgical procedures and post-operative weight bearing were determined by the surgeons’ decisions. Patients with poor performance status might need better preoperative evaluation, leading to longer preoperative periods, and less invasive methods could have been selected. Fourth, the perioperative environments and protocols may differ among the participating hospitals, including the availability of operating rooms, preoperative examinations or requirements, and postoperative protocols for rehabilitation. Fifth, long-term functional outcomes after evaluating the ambulation recovery were lacking.

Conclusions

In this study, postoperative recovery of ambulation was an independent prognostic factor related to reduced one-year mortality in older adults undergoing fracture surgery for femoral metastasis. Additionally, the rate of postoperative chemotherapy was significantly higher in the patients who recovered ambulation than in those who did not, indicating clinical benefits for the patients who can show ambulation recovery postoperatively. Furthermore, in the subgroup of patients with CF, the patients who recovered ambulation postoperatively had shorter preoperative waiting times. Therefore, to promote better clinical outcomes in older adults with CF of the femur, prompt surgical intervention should be considered when a femoral fracture is diagnosed due to metastasis.

Data availability

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CF:

-

Complete pathological fracture

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- ECOG-PS:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status

- IF:

-

Impending pathological fracture

References

Meng, Y. et al. Goosecoid promotes pancreatic adenocarcinoma metastasis through TGF-β signaling. Cell. Mol. Biol. (Noisy-le-grand). 70, 100–105. https://doi.org/10.14715/cmb/2024.70.7.14 (2024).

Blagov, A. V. et al. The role of mitochondria in metastasis development. Cell. Mol. Biol. (Noisy-le-grand). 70, 171–178. https://doi.org/10.14715/cmb/2024.70.1.23 (2024).

Tharmalingam, S., Chow, E., Harris, K., Hird, A. & Sinclair, E. Quality of life measurement in bone metastases: A literature review. J. Pain Res. 1, 49–58. https://doi.org/10.2147/jpr.s4572 (2008).

Zheng, Z., Hu, Y., Ren, Y., Mo, G. & Wan, H. Correlation between metastatic patterns and age in patients with metastatic primary liver cancer: A population-based study. PLoS One. 18, e0267809. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0267809 (2023).

Zhang, C. et al. The prevalence, associated factors for bone metastases development and prognosis in newly diagnosed ovarian cancer: a large population based real-world study. J. Cancer. 10, 3133–3139. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.30335 (2019).

Hu, Z. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of bone metastasis and the development of bone metastatic prognostic classification system: a pan-cancer population study. Aging (Albany NY). 15, 13134–13149. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.205224 (2023).

Knapp, B. J., Devarakonda, S. & Govindan, R. Bone metastases in non-small cell lung cancer: a narrative review. J. Thorac. Dis. 14, 1696–1712. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd-21-1502 (2022).

Chen, X. Y. et al. Risk factors for bone metastasis from renal cell cancer. J. Bone Oncol. 9, 29–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbo.2017.10.004 (2017).

Kadeerhan, G., Xue, B., Wu, X. L., Chen, W. N. & Wang, D. W. Incidence trends and survival of metastatic prostate cancer with bone and visceral involvement: 2010–2019 surveillance, epidemiology, and end results. Front. Oncol. 13, 1201753. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.1201753 (2023).

Nishimoto, T. et al. Intervention for impending pathological fractures at proximal femur is associated with lower mortality rates in patients with intermediate-to-high risk according to the Katagiri-New score. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 25, 836. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-024-07838-8 (2024).

Yanagisawa, S. et al. Comparison of the clinical outcomes of intramedullary nailing between impending and completed pathological fractures caused by metastatic femoral tumors from solid cancers. J. Orthop. Sci. 29, 1119–1124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jos.2023.07.001 (2024).

Kim, Y., Krishnan, C. K., Kim, H. S., Cho, H. S. & Han, I. Ambulation recovery after surgery for metastases to the femur. Oncologist 25, e178–e185. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0107 (2020).

English, K. L. & Paddon-Jones, D. Protecting muscle mass and function in older adults during bed rest. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 13, 34–39. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCO.0b013e328333aa66 (2010).

Covinsky, K. E. et al. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 51, 451–458. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51152.x (2003).

Zhuang, J., Wang, J., Zhang, B., Chai, D. & Zuo, Z. The prophylactic effects of naringin on steroid-induced early-stage osteonecrosis in rats: a preliminary study. Cell. Mol. Biol. (Noisy-le-grand). 69, 94–104. https://doi.org/10.14715/cmb/2023.69.5.16 (2023).

Groot, O. Q. et al. Clinical Outcome Differences in the Treatment of Impending Versus Completed Pathological Long-Bone Fractures. JBJS 104 (2022).

Hershkovich, O. et al. Femoral metastatic pathological fractures, impending and actual fractures – A patient survival study. Surg. Oncol. 51, 102014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suronc.2023.102014 (2023).

O’Connor, M. I. & Switzer, J. A. AAOS clinical practice guideline summary: management of hip fractures in older adults. JAAOS - J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 30, e1291–e1296. https://doi.org/10.5435/jaaos-d-22-00125 (2022).

Network, S. I. G. Management of Hip Fracture in Older People: a National Clinical Guideline (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), 2009).

Lizaur-Utrilla, A. & Lopez-Prats, F. A. Hip attack for hip fractures: is ultra-early surgery necessary? Lancet 395, 661–662. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30156-2 (2020).

Seong, Y. J., Shin, W. C., Moon, N. H. & Suh, K. T. Timing of Hip-fracture surgery in elderly patients: literature review and recommendations. Hip Pelvis. 32, 11–16. https://doi.org/10.5371/hp.2020.32.1.11 (2020).

Doruk, H., Mas, M. R., Yildiz, C., Sonmez, A. & Kýrdemir, V. The effect of the timing of hip fracture surgery on the activity of daily living and mortality in elderly. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 39, 179–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2004.03.004 (2004).

Al-Ani, A. N. et al. Early operation on patients with a hip fracture improved the ability to return to independent living. A prospective study of 850 patients. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 90, 1436–1442. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.G.00890 (2008).

Prigerson, H. G. et al. Chemotherapy use, performance status, and quality of life at the end of life. JAMA Oncol. 1, 778–784. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2378 (2015).

Mirels, H. Metastatic disease in long bones. A proposed scoring system for diagnosing impending pathologic fractures. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res., 256–264 (1989).

Katagiri, H. et al. New prognostic factors and scoring system for patients with skeletal metastasis. Cancer Med. 3, 1359–1367. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.292 (2014).

Sasaki, K. et al. Implementation status of postoperative rehabilitation for older patients with hip fracture in Kyoto City, Japan: A population-based study using medical and long-term care insurance claims data. PLoS One. 19, e0307889. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0307889 (2024).

Beaupre, L. A., Carson, J. L., Noveck, H. & Magaziner, J. Recovery of walking ability and return to community living within 60 days of hip fracture does not differ between male and female survivors. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 63, 1640–1644. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13535 (2015).

Hiraga, H. et al. Methotrexate, doxorubicin, and cisplatin versus methotrexate, doxorubicin, and cisplatin + Ifosfamide in poor responders to preoperative chemotherapy for newly diagnosed High-Grade osteosarcoma (JCOG0905): A multicenter, Open-Label, randomized trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 0, JCO–24. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO-24-01281 (2025).

Dall, C. H., Andersen, H., Povlsen, T. M. & Henriksen, M. Evaluation of a technology assisted physical activity intervention among hospitalised patients: A randomised study. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 69, 50–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2019.08.019 (2019).

Izquierdo, M. et al. International exercise recommendations in older adults (ICFSR): expert consensus guidelines. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 25, 824–853. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-021-1665-8 (2021).

Gralow, J. R. et al. NCCN task force report: bone health in Cancer care. J. Natl. Compr. Canc Netw. 7 (Suppl 3). https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2009.0076 (2009). S1-32; quiz S33-35.

Boddapati, V. et al. Risks and Complications After Arthroplasty for Pathological or Impending Pathological Fracture of the Hip. J Arthroplasty 36, 2049–2054.e (2045). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2021.02.004 (2021).

Boddapati, V. et al. Risks and Complications After Arthroplasty for Pathological or Impending Pathological Fracture of the Hip. The Journal of Arthroplasty 36, 2049–2054.e (2045). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2021.02.004 (2021).

Liu, Q. & Xu, K. Evaluation of some cellular biomarker proteins, oxidative stress and clinical indices as results of laparoscopic appendectomy for perforated appendicitis in children. Cell. Mol. Biol. (Noisy-le-grand). 66, 197–203 (2020).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KI and TN collected the data, assisted by DT, TShimizu, HH, and TSsoma. HS designed the study, supervised by MM. HS wrote the manuscript and illustrated the figures. NI and AI directed the entire study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the local ethics committees of Hokkaido University Hospital (022–0036) and the other participating hospitals. Informed consent was obtained by the opt-out method. No data related to these participants were included in the analysis. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of human ethics set forth by the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ito, K., Shimizu, H., Matsuoka, M. et al. Recovery of ambulation in older adults undergoing fracture surgery for femoral metastasis: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 16578 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01126-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01126-8