Abstract

Nitrate (NO3–) is a crucial component of atmospheric pollutants, and understanding its sources and formation mechanisms holds significant importance for air pollution control. In this study, stable isotope techniques and Bayesian Mixing Models (Mix SIAR) were applied to analyze the primary sources and formation processes of NO3− in PM2.5 and PM10 in Beijing in 2022. The results indicate that the contribution of vehicle exhaust, coal combustion, biomass burning, and soil emissions to NO3− in PM2.5 were 33.9%, 20.5%, 29.8%, and 15.9%, respectively, while for PM10, the contributions were 30.6%, 21.6%, 29.9%, and 17.9% respectively. An analysis of δ18O-NO3− values indicated that the contribution of N2O5 hydrolysis to NO3− in PM2.5 and PM10 over the year was 64.0% and 75.6%, respectively, highlighting its predominant role in nitrate formation. Nevertheless, the gas-phase reaction of NO2 with ·OH radicals was notably more pronounced in summer. Compared to PM10, the gas-phase reaction of NO2 with ·OH radicals contributes more to NO3− in PM2.5. These results offer a vital foundation for further research into the sources and formation mechanisms of atmospheric NO3− and provide scientific support for measures to prevent and control air pollution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the global crisis of air pollution intensifies, fine particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10) composition and related hazards have become pivotal research subjects1,2,3. Such particulate matter can infiltrate the respiratory tract, inducing respiratory and cardiovascular diseases4,5, and can impact human life expectancy6. Nitrate (NO3–), a primary constituent of fine particulate matter, not only significantly influences air quality7,8, but also plays a key role in the nitrogen cycle9. Atmospheric accumulation of NO3– is closely tied to acid rain formation and precipitates ecological issues such as water body eutrophication and soil acidification10. These environmental changes pose potential threats to ecosystems and human health, especially by increasing the risk of water pollution and respiratory diseases. Hence, traceability research on nitrates is crucial for effectively controlling nitrate emissions and ensuring environmental quality.

The atmospheric precursors to NO3– are nitrogen oxides (NOX) (NO + NO2). These compounds undergo intricate oxidation processes in the atmosphere to yield NO3–11,12. Currently, two primary pathways for the conversion of NOX to NO3– are acknowledged: the gas phase reaction between NO2 and ·OH radicals and the heterogeneous-phase reaction resulting from N2O5 hydrolysis13. Upon entering the atmosphere, NOX swiftly interacts with O3 or HO2/RO2, producing NO2. This subsequently reacts with ·OH to generate HNO313,14, which is the predominant nitrate formation pathway during the daylight and is light-dependent. During nighttime, given the markedly low concentration of ·OH, HNO3 cannot be directly synthesized from NO2 oxidation. Instead, NO2 is initially oxidized by O3, forming NO3, which then reacts with either dimethyl sulfide (DMS) or hydrocarbons (HC) to produce HNO3. Alternatively, NO3 may amalgamate with NO₂, leading to the formation of N2O5, which subsequently hydrolyzes to yield HNO311,15.

In recent years, stable isotope tracing technology, an advanced analytical tool, has proven significantly advantageous for examining the sources and transformation processes of NO3– in atmospheric PM2.5 and PM1012,16,17,18. The predominant research methodology in this field currently involves utilizing stable isotope mass spectrometry to ascertain the isotopic values of elements. These findings are then integrated with the Bayesian Mixing Model (Mix SIAR) to analyze the contribution from NOX emission sources to atmospheric NO3– and to delineate the pathways involved in the conversion NOX forming NO3–.

Different nitrogen oxide emission sources have different nitrogen and oxygen isotope values. By analyzing the stable isotopic values of 15N in NO3– present in atmospheric particulate matter and comparing them with the δ15N values from various sources, scientists can effectively trace the origins of atmospheric NO3–19,20. Typical sources of NOX in the atmosphere encompass biomass burning, coal combustion, vehicle exhaust emissions, and soil emissions. The δ15N values for NOX emitted from gasoline vehicle exhaust range from − 12.2‰ to − 9.8‰21, whereas the δ15N-NOX values from coal combustion emissions are notably higher, averaging 13.5 ± 4.9‰22. The δ15N-NOX released from biomass burning (including open burning and rural stoves) are − 3.7‰ to 3.1‰ and − 11.9‰ to 1.5‰, respectively23. The δ15N-NOX values from soil emissions have a wide range of − 30.8‰ to − 26.5‰4. Moreover, the diverse pathways by which NO2 is converted to NO3–, coupled with the different δ18O values among various oxidants, yield distinct δ¹⁸O-NO3– values in the resultant NO3–. In the N2O5 pathway, O3 contributes five-sixths of the oxygen atoms, whereas in the ·OH pathway, two-thirds of the oxygen atoms are sourced from O318,25,26. Consequently, one anticipates that the δ18O of nitrate synthesized via the N2O5 pathway is elevated compared to that produced through the ·OH pathway27. As a result, the δ18O-NO3– values in the atmosphere serve as indicators for studying the formation processes of atmospheric NO3–28,29. A comprehensive analysis of both nitrogen and oxygen isotopic ratios offers enhanced precision in determining the sources of NO3– in atmospheric particulate matter.

The Mix SIAR is a statistical model that operates within the Bayesian statistical framework and addresses the issue of mixed distributions in data30. This model quantifies the contributions from various emission sources, including industrial emissions, vehicle exhaust and natural sources, to atmospheric particulate matter. This is achieved by analyzing the chemical composition and isotopic ratios of atmospheric particulate matter18,31. In recent years, significant advancements have been made using the Mix SIAR in the field of environmental science, especially in the study of sources and transformation processes of NO3– in atmospheric particulate matter18,28,32,33,34. This model has proven to be an exceptional analytical method.

In recent years, Beijing has enacted a series of air pollution control policies with the objective of enhancing environmental quality and reducing air pollution levels19,35,36. These efforts have achieved significant results, leading to a noticeable improvement in urban air quality. Historically, the highest concentration of secondary inorganic ions in the atmosphere was sulfate, a byproduct of coal combustion37,38. However, the implementation of pollution prevention policies has shifted the dominant secondary inorganic ion in Beijing’s atmospheric particulate matter has changed from sulfate to nitrate39,40. Consequently, it is imperative to conduct the source tracing studies of NO3–.

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the origins and transformation processes of NO3– in Beijing’s atmosphere, an in-depth source apportionment and pathway analysis were conducted on NO3– present in atmospheric particulate matter PM2.5 and PM10 during 2022. This was achieved through the examination of nitrogen and oxygen isotopic ratios found in particulate matter. The study’s findings illuminated the contributions from various pollution sources in Beijing, thereby providing a scientific foundation for subsequent environmental policy development and further advancing atmospheric governance efforts within the city.

Methods

Sampling

The atmospheric particulate matter samples were collected on the rooftop of a building within the Institute of High Energy Physics in Shijingshan District, Beijing (39.91° N, 116.25° E). The sampling site is between the Fourth and Fifth Ring Roads of Beijing, surrounded by schools with no major emission sources, reflecting the air pollution status of the urban area of Beijing. Beijing is situated in the northern region of the North China Plain, characterized by a complex topography that includes mountains to the north and west and plains to the southeast. Beijing experiences four distinct seasons, with cold and dry winters and frequent temperature inversions that hinder the dispersion of pollutants. Different climatic conditions lead to varying air pollution levels in different seasons. January, April, July, and October of 2022 were selected to represent different seasons, and sampling analyses were conducted on days with AQI greater than 70. 30 samples each of PM2.5 and PM10 were collected. Two high-flow atmospheric particulate samplers, the TE-6070-PM2.5 and TE-6070-PM10 (TISCH Environmental), were employed to concurrently collect PM2.5 and PM10 samples. Operating at a flow rate of 1.05 m3/min, these samplers gathered samples over a 24-hour period, achieving an approximate total volume of 1512 m3. The particulate matter was captured on polypropylene fiber filters, measuring 203 × 254 mm (MemberSpace, USA). Before sampling, the filters were weighed three times, and the average was calculated. However, the implementation of pollution prevention policies has shifted the dominant secondary inorganic ion in Beijing’s atmospheric particulate matter has changed from sulfate to nitrate. After sampling, the samples were stored in a freezer at − 20 ℃, dried and weighed before analysis, with each sample weighed three times and the average value used for subsequent analysis.

Analysis of water-soluble inorganic ions and stable isotopes

The sample films were cut into 2 cm × 2 cm pieces. Water-soluble inorganic ions (WSII) were extracted using 35 mL of deionized water, shaken at 170 rpm for 40 min, and then ultrasonicated for 20 min. Afterward, the samples were filtered with a 0.22 μm syringe filter and later tested by ion chromatography (an AS-AP autosampler was integrated into a Thermo Scientific Dionex Integrion HPIC system). An anion suppressor was used in conjunction with an AS14A4 250 mm column for anion analysis. The ion chromatography system was equipped with a KOH eluent generator, using deionized water as the eluent, and the eluent was set to 30 mM with a flow rate of 1 mL/min. To ensure quality control, standard samples were inserted every 20 samples. The detection limit of the ion chromatography is 0.013 µg/mL.

The extracted solution was treated using denitrifier method30,41, where Pseudomonas chlororaphis subsp. aureofaciens (ATCC 13985, DSM 6698) was used to convert NO3− in the solution to N2O gas. Subsequently, the gas stable isotope ratios of δ15N and δ18OVSMOW in the samples were analyzed using a gas isotope ratio mass spectrometer (MAT 253, Thermo Fisher, USA), a multi-purpose online gas preparation system (Gas-Bench II, Thermo Fisher, USA), and an N2O pre-enrichment device. Standard materials such as USGS-34 (δ15N = − 1.8‰, δ18OVSMOW = − 27.9‰), USGS-35 (δ15N = 2.7‰, δ18OVSMOW = 57.5‰), and IAEA-NO-3 (δ15N = 4.7‰, δ18OVSMOW = 25.6‰) were used for data calibration.

The δ15N value is calculated using the following formula with nitrogen gas in the air as the reference standard:

The δ15N value represents the per mil difference in the stable nitrogen isotope ratio of the sample relative to the stable nitrogen isotope ratio of nitrogen gas in the air. R(15N/14N)sample is the nitrogen isotope abundance ratio in the sample, and R(15N/14N)air is the nitrogen isotope abundance ratio in the air.

The δ18OVSMOW value is calculated using the following formula with VSMOW as the reference standard:

The δ18O value represents the per mil difference in the stable oxygen isotope ratio of the sample relative to the stable oxygen isotope ratio of standard mean ocean water. R(18O/16O)sample is the oxygen isotope abundance ratio in the sample, and R(18O/16O)VSMOW is the oxygen isotope abundance ratio in standard mean ocean water.

The Bayesian Mixing Model

The Bayesian Mixing Model (Mix SIAR) is employed to compute the fractionation factors among nitrogen oxides and NO3–, while also providing an estimation of the formation process and potential sources for atmospheric nitrate aerosols31. Here we use R Studio to run the Mix SIAR. This model can be depicted as:

Formula (3) is an equation based on the principle of mass balance, where Xij represents the δ value of isotope j in mixture i (i = 1, 2, 3, …, N; j = 1, 2, 3, …, J); Pk is the proportion of source k to be calculated, Sjk is the δ value of isotope j in source k (k = 1, 2, 3, …, K); Cjk is the fractionation factor of isotope j in source k (with mean value λ and standard deviation τ); εij represents the residual error. Formula (4) indicates that Sjk, Cjk, and εij all follow a normal distribution. The values of various emission sources used in the Mix SIAR model are presented in Table 1.

According to Zong’s method18,19,34, Monte Carlo simulations of the measured values of PM2.5 and PM10, δ18O-NO3– were performed to generate 1000 feasible solutions of ƒOH, which was defined as the error between the predicted value and the measured value of δ18O-NO3– of less than 0.5. δ18O-NO2 ranges from 90‰ to 122‰. And δ18O-N2O5 ranges from 121.4‰ to 131.4‰. The range of δ18O-H2O is − 25‰ to 0‰. The contribution of the different pathways was finally obtained. ƒN2O5 was calculated by 1-ƒ·OH. The Monte Carlo models were run using Python.

Results and discussion

The concentration of PM2.5, PM10 and NO3 – found in particulate matter

The average PM2.5 concentration was 80.5 µg/m3, with a range of 18.2 µg/m3 to 183.4 µg/m3, while the mean PM10 concentration was 124.1 µg/m3, with a span of 32.7 µg/m3 to 261.1 µg/m3. There was a marked seasonal fluctuation in PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations for the year 2022. The highest pollution levels were noted in spring, with PM2.5 and PM10 at 129.1 µg/m3 and 181.9 µg/m3, respectively, likely due to the significant influence of sand and dust storms. Winter followed as the second most polluted season, with PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations at 70.8 µg/m3 and 109.8 µg/m3, respectively, largely due to increased heating activities and unfavorable weather conditions for pollutant dispersion. Conversely, concentrations were relatively low in summer, with PM2.5 and PM10 at 23.1 µg/m3 and 49.4 µg/m3, respectively, thanks to the dilution effect of high temperature convection and precipitation. The concentrations of PM2.5 and PM10 in the autumn air were 65.5 µg/m3 and 112.5 µg/m3, respectively.

Concentrations of NO3–, PM2.5, PM10 and δ15N-NO3– and δ18O-NO3– values in PM2.5 (a) and PM10 (b) samples (the bar chart represents the NO3– concentration, the blue dotted line represents δ15N-NO3–, the green dotted line represents δ18O-NO3–, and the orange dotted line represents the concentration of particulate matter).

The annual mean concentration of NO3– was 17.4 µg/m3, with a range from 0.4 µg/m3 to 54.9 µg/m3. The peak mean NO3– concentration occurred in autumn, registering 20.5 µg/m3 in PM2.5 and 31.5 µg/m3 in PM10. Conversely, the lowest mean concentration was observed in summer, measuring 3.7 µg/m3 in PM2.5 and 11.9 µg/m3 in PM10. Atmospheric HNO3 exhibits high volatility, whereas NH4NO3 is a semi-volatile compound, both of which undergo thermodynamic partitioning between the gas phase and particles48,49. Consequently, conditions of low temperature and high relative humidity promote the conversion of atmospheric gases into ionic compounds through either homogeneous or non-homogeneous reactions. This process is influenced by environmental conditions such as temperature and relative humidity. Low temperatures and high relative humidity encourage the conversion of these atmospheric gases into ionic compounds via either homogeneous or non-homogeneous reactions. Consequently, conditions typical of autumn and winter, characterized by low temperatures and high relative humidity, facilitate this conversion. In contrast, during summer, factors such as robust atmospheric convection and frequent rainfall augment the cleansing effect on pollutants, subsequently mitigating air pollution.

The δ15N and δ18O values of nitrate

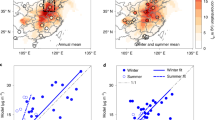

The ranges and means of δ15N-NO3– and δ18O-NO3– values in PM2.5 and PM10 from Beijing were similar (Fig. 1). The δ15N-NO3– values in PM2.5 varied between − 3.3‰ and 15.0‰, with an average of 3.3‰ ± 5.3‰. In PM₁₀, δ15N-NO3– ranged from − 4.0‰ to 15.6‰, with an average of 2.9‰ ± 5.7‰. δ15N-NO3– values for PM2.5 were comparable to those previously reported levels for Beijing (from − 2.3‰ to 19.7‰ with an average of 7.3‰ ± 5.4‰)25, and to those observed in Hangzhou (1.1‰ to 9.2‰)34 and Shanghai (− 2.9‰ to 18.1‰)50. The δ18O-NO3− values in PM2.5 varied from 18.3‰ to 102.2‰ with a mean of 73.0‰ ± 20.1‰, while the δ18O-NO3– values in PM10 ranged from 36.7‰ to 95.4‰ with an average of 78.4‰ ± 14.6‰. The δ18O-NO3– values recorded at the North Imperial City Island Monitoring Station spanned from 49.4‰ to 103.9‰18, with values recorded in Shijiazhuang ranging from 50.3‰ to 103.0‰51 and in Qingdao, values were found to be between 53.4‰ and 83.7‰, with an average of 67.3‰ ± 5.0‰52. Our δ18O-NO3– values fell within a similar δ18O range.

The correlations of δ15N-NO3– and δ18O-NO3– with temperature in PM2.5 and PM10 are significantly negative (δ15N-NO3–: PM2.5: r = − 0.663, p < 0.01; PM10: r = − 0.714, p < 0.01), (δ18O-NO3–: PM2.5: r = − 0.579, p < 0.01; PM10: r = − 0.722, p < 0.01). This indicates that as the temperature rises, the values of δ15N-NO3– and δ18O-NO3– decrease. At lower temperatures, nitrification and N2O5 hydrolysis reactions decelerate, causing a relative enrichment of the heavy isotopes15N and18O) and subsequently higher δ15N and δ18O values53. In winter, reduced solar radiation can inhibit the ·OH oxidation reaction pathway, leading to elevated δ18O-NO3– values. The clear seasonal variations in δ¹⁵N and δ18O values within PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations underscore this phenomenon. The overall sequence of δ15N-NO3– is as follows: winter (PM2.5: 9.1 ± 5.5‰; PM10: 9.5 ± 4.6‰) > spring (PM2.5: 1.0 ± 2.3‰; PM10: − 0.3 ± 3.5‰) ≈ autumn (PM2.5: 0.8 ± 3.1‰; PM10: 0.3 ± 3.1‰) > summer (PM2.5: 0.3 ± 2.9‰; PM10: 0.1 ± 2.5‰), while the trend for δ18O-NO3– is winter (PM2.5: 85.5 ± 19.4‰; PM10: 90.1 ± 5.1‰) > autumn (PM2.5: 79.2 ± 13.5‰; PM10: 83.0 ± 7.0‰) > spring (PM2.5: 66.5 ± 19.0‰; PM10: 71.9 ± 13.9‰) > summer (PM2.5: 846.8 ± 13.1‰; PM10: 57.9 ± 14.6‰). δ18O-NO3– values often distinguish the formation mechanisms of NOX conversion to NO3–. Winter conditions, marked by low temperatures, stable atmospheric conditions, and heightened heating activities, notably expedite the hydrolysis of N2O5, producing nitrates with higher δ18O-NO3– values. In contrast, during summer, elevated temperatures promote the conversion of NOX via the ·OH oxidation pathway, resulting in nitrates with diminished δ18O-NO3− values26,27.

Estimating nitrate source contributions using the Mix SIAR model

The Mix SIAR model was utilized to quantify the contributions from vehicle exhaust, coal combustion, biomass burning, and soil emissions as the sources of NOX to the NO3– in PM2.5 and PM10 (Fig. 2). The contributions of NO3– from vehicle exhaust, coal combustion, biomass burning, and soil emissions to PM2.5 were 33.9%, 20.5%, 29.8%, and 15.9%, respectively, and to PM10, they were 30.6%, 21.6%, 29.9%, and 17.9%, respectively. The source compositions for PM2.5 and PM10 are notably consistent, suggesting a uniform influence from their respective sources. This indicates that both fine and coarse particulate matter in urban environments are predominantly influenced by transportation and biomass burning.

Our findings indicate that the contribution of coal combustion is lower compared to the source apportionment results for Beijing during 2013~2014, which were reported as 40.4% ± 12.3%32. Beijing has enacted various air pollution mitigation strategies, including the relocation of factories and the adoption of new energy sources, leading to a marked reduction in coal consumption within the region51,54. The official data shows that the coal consumption in Beijing has decreased from 21.79 million tons (in 2012) to less than 1.5 million tons (in 2021), which accounts for less than 1.5% of the total energy consumption in Beijing, and thus substantial progress has been made in the energy structure adjustment in Beijing. The contribution of biomass burning is consistent with the findings of several previous studies19,25,32. Biomass burning mainly includes the burning of agricultural waste and wood for cooking and heating in rural areas. In addition, the higher contribution of biomass combustion in this study might be due to the overlap between biomass combustion and vehicle emission δ15N-NO3– values, which leads to an overestimation of the contribution of biomass combustion19.

The 2013 simulation of Beijing by Cheng et al. revealed that vehicle exhaust was the primary contributor to NOX emissions, accounting for 67.2%55. In contrast, our analysis indicates a significant reduction in such emissions, although mobile sources still constitute the majority. The rising trend in the number of motor vehicles in Beijing is evident; statistics reveal that in 2022, there were 7.128 million motor vehicles, marking an increase of 278,000 from 202156. This partly explains the relatively high contribution of vehicle emissions to atmospheric NO3– concentrations. Electric vehicles (EVs) offer the potential for significant NOX emission reductions57. Beijing is actively promoting the adoption of EVs to replace gasoline-powered vehicles in an effort to mitigate the contribution of vehicle exhaust to air pollution, with some success. By the end of 2022, the number of new energy vehicles in Beijing was approximately 617,000 and growing. However, gasoline vehicles still constitute the majority of vehicles in Beijing, potentially maintaining a high contribution of vehicle emissions to NO3–. China has set a goal for battery electric vehicles to comprise 50% of the market by 203557, which should further reduce the contribution of vehicle exhaust to atmospheric NO3– levels.

Soil emissions contributed 15.9% and 17.9% to PM2.5 and PM10, respectively, which was consistent with the results of Song et al.25 and Zong et al.32 in Beijing. The sampling site is mainly surrounded by urban parks and green spaces with rich vegetation coverage and active soil microorganisms, which could produce NOX.

Mix SIAR model assessments for NO3− were also performed across varying seasons, revealing analogous contribution values from different sources to NO3– in PM2.5 and PM10 were similar (Fig. 2). During the spring, summer, and autumn, vehicle exhaust was the prominent source of pollution (29.7~30.6%). However, in winter, the contribution from vehicle exhaust drops to 24%, while coal combustion and biomass burning become the dominant sources, contributing 38.1% and 29.2%, respectively. The increase in coal combustion and biomass burning for winter heating may be the cause of this. The contribution from winter coal combustion is less than 50%, as reported in the 2018 source allocation study by Fan et al.19, indicating progress in Beijing’s energy profile restructuring. Biomass burning maintains a consistent contribution throughout the year, with a slight rise during winter. Agricultural activities peak in the spring and autumn, leading to a significant source of biomass burning from crop residue burning. In winter, biomass combustion is more frequently used for heating. Furthermore, winter is the post-harvest season for agricultural crops, resulting in the availability of large amounts of agricultural waste (e.g., straw, corn cobs), which are often used as biomass fuel58. The combustion of these wastes not only elevates the emission of particulate matter but may also potentially release considerable amounts of nitrogen oxides and sulfur oxides59. Soil emissions remain stable during the spring, summer, and autumn (22.2~23.7%) but decline to 8.7% in winter. These variations can be attributed to the robust plant growth, heightened soil microbial activity, and the increased frequency of nitrogen transformation processes occurring during spring, summer, and autumn. Conversely, the cold weather in winter significantly reduces microbial activity in the soil, leading to a decrease in the NO3− contribution from soil emissions58.

Assessment of NO3 − formation pathways

The use of δ18O-NO3− allows for the evaluation of long-term trends in NOX oxidation reactions and the atmospheric oxidation capacity. The formation of NO3− in near-surface atmospheric secondary particles primarily occurs through two pathways: the gas-phase reaction of NO2 with ·OH radicals and the hydrolysis of N2O518,25,34.

The analytical results indicate that the hydrolysis of N2O5 accounts for 64.0% and 75.6% of NO3− in PM2.5 and PM10, respectively. This suggests a dominant role for the hydrolysis of N2O5 in the production of atmospheric NO3−. Stable isotope analysis providing δ18O-NO3− values can quantify the contributions of these two oxidation pathways to the overall reaction18,25. Our results are similar to those of Wang et al. (69%)33, and are close to the test results of Fan et al. when the PM2.5 concentration exceeded 150 µg/m3 (nitrate generated via the N2O5 + H2O pathway accounted for 64%)19. It is important to note that our sampling was carried out on days with high AQI values. Elevated concentrations of particulate matter during these periods could potentially enhance the activity of the N2O5 hydrolysis pathway19,52. This occurrence can potentially be ascribed to the diminished radiation, due to the prevalence of particulate matter in the atmosphere during haze conditions. The reduction in photochemical oxidation consequently leads to a decreased concentration of free radicals. This subsequently reduces the reaction between NO2 and ·OH60.

This pattern was consistently observed across different seasons: in winter (PM2.5: 66.7%, PM10: 69.8%), spring (PM2.5: 61.7%, PM10: 65.2%), and autumn (PM2.5: 77.2%, PM10: 85.2%). This trend is similar to the findings of Deng et al. in the study in 2018–2019 in Wuhan61. The larger contribution of N2O5 + H2O in autumn may be due to the higher average relative humidity (74%); this offers more suitable reaction conditions for the pathway of N2O5. In winter, the contribution rate of NO3− from the hydrolysis of N2O5 was found to be slightly higher than that in Shanghai in winter (20.7 ± 11.5%)62. In winter, ·OH generation decreases because of weaker sunlight and lower photochemical reaction intensity, which leads to lower ·OH concentrations. The decomposition of N2O5 is also slowed by the low temperatures in winter61. Wang et al., suggested that the contribution of the NO2+·OH pathway to NO3− generation was 27 ± 12% in Beijing in spring33, which was lower than our result in spring. This might be related to the reduction in haze pollution in spring in 2022, which led to better air quality and stronger photochemical reactions.

During summer, the gas-phase reaction between NO2 and ·OH radicals is significantly heightened, contributing to 91.3% of PM2.5 and 67.8% of PM10. The results of the pathway analysis in our PM10 are similar to those of Huang et al., where they found that gas-phase reactions generated 70.5 ± 17.0% of NO3− in summer62. This increase can be attributed to the longer daylight hours, intense solar radiation, and higher temperatures that encourage the reaction between NO2 and ·OH. However, the limited size of our summer sample may introduce some uncertainty into the results regarding the distribution of contributions.

Our research also revealed that the gas-phase reaction of NO2 with ·OH radicals is the primary contributor to NO3− formation in PM2.5, while the hydrolysis of N2O5 plays a more significant role in PM10. In our previous study, the mean value of water-soluble inorganic ion (WSII) concentration in PM10 was 49.4 µg/m3, which was slightly higher than the mean value of WSII in PM2.5 of 42.2 µg/m3. The higher WSII concentrations could have resulted in greater hygroscopicity, leading to stronger water absorption in PM10 compared to PM2.5, which is consistent with our current findings. Furthermore, the larger aerosol surface area (Sa) of PM10 enhances the hydrolysis of N2O563,64,65. Research by Gaston & Thornton has also shown that the rate of N2O5 uptake on larger particles either increases or remains constant as the particle size increases66, further explaining why N2O5 hydrolysis has a greater impact on NO3− in PM10.

Conclusion

In this study, the Mix SIAR was applied to analyze the nitrogen and oxygen isotope ratios of NO3− in samples. The aim was to explore the sources of NO3− and its formation processes in atmospheric PM2.5 and PM10 in Beijing during the four months of 2022. The δ15N-NO3− values for PM2.5 and PM10 in the Beijing area ranged from − 3.3‰ to 15.0‰ (3.3‰ ± 5.3‰) and − 4.0‰ to 15.6‰ (2.9‰ ± 5.7‰), respectively. Similarly, the δ18O-NO3− values ranged from 18.3‰ to 102.2‰ (73.0‰ ± 20.1‰) for PM2.5 and from 36.7‰ to 95.4‰ (78.4‰ ± 14.6‰) for PM10. Notably, δ¹⁵N-NO3− and δ¹⁸O-NO3− exhibited similar patterns in both PM2.5 and PM10.

The δ15N-NO3− values were incorporated into the Mix SIAR, and the subsequent calculations indicated that the different sources contributed similarly to NO3− in PM2.5 and PM10. The contributions from vehicle exhaust, coal combustion, biomass burning, and soil emission to PM2.5 and PM10 were found to be 33.9%, 20.5%, 29.8%, and 15.9% respectively, and 30.6%, 21.6%, 29.9%, and 17.9%, respectively. The findings indicate that both fine and coarse particles in the vicinity of the sampling site are markedly influenced by vehicular traffic and soil sources. An analysis of seasonal variations revealed that the results for spring, summer, and autumn aligned with the annual findings, while in winter, biomass burning and vehicle exhaust emerged as the primary sources of NO3− in the atmosphere.

The analysis of δ18O-NO3− values demonstrated that N2O5 hydrolysis contributed to 64.0% and 75.6% of NO3− in PM2.5 and PM10, respectively, suggesting its dominant role in atmospheric nitrate formation throughout the year. However, during summer, the gas-phase reaction between NO2 and ·OH radicals was significantly enhanced due to strong sunlight, high temperatures, and high humidity. Furthermore, our findings indicate that the hydrolysis reaction of N2O5 contributes slightly more in PM10 compared to PM2.5. This difference is likely due to higher WSII concentration and greater surface area in PM10.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript. Data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Liu, G., Dong, X., Kong, Z. & Dong, K. Does National air quality monitoring reduce local air pollution? The case of PM2.5 for China. J. Environ. Manage. 296, 113232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113232 (2021).

Xu, X. & Zhang, T. Spatial-temporal variability of PM2.5 air quality in Beijing, China during 2013–2018. J. Environ. Manage. 262, 110263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110263 (2020).

Yang, X. et al. Comparison of Ground-Based PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations in China, India, and the U.S. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 15, 1382. http://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15071382 (2018).

Chen, C. et al. The effect of air pollution on hospitalization of individuals with respiratory and cardiovascular diseases in Jinan. China Med. 98, e15634. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000015634 (2019).

Feng, W. et al. Short-term PM10 and emergency department admissions for selective cardiovascular and respiratory diseases in Beijing, China. Sci. Total Environ. 657, 213–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.066 (2019).

Zhang, Q. et al. Overview of particulate air pollution and human health in China: evidence, challenges, and opportunities. Innov. 3, 100312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xinn.2022.100312 (2022).

Hang, Y. et al. Assessment of long-term particulate nitrate air pollution and its health risk in China. iScience 25, 104899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2022.104899 (2022).

Zhang, Z. et al. Nitrate pollution deterioration in winter driven by surface Ozone increase. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 4123. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00667-5 (2024).

Bose, S. et al. Prenatal nitrate air pollution exposure and reduced child lung function: timing and fetal sex effects. Environ. Res. 167, 591–597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2018.08.019 (2018).

Liu, X. et al. Comparative effects of simulated acid rain of different ratios of SO42 – to NO3 – on fine root in subtropical plantation of China. Sci. Total Environ. 618, 336–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.11.073 (2018).

Peng, J. et al. Application of stable isotopes in identifying the sources and formation of sulfate and nitrate in PM2.5: a review. Atmosphere 15, 1312. http://doi.org/10.3390/atmos15111312. (2024).

Zhen, S., Luo, M., Shao, Y., Xu, D. & Ma, L. Application of stable isotope techniques in tracing the sources of atmospheric NOX and nitrate. Processes 10, 2549. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr10122549 (2022).

Alexander, B. et al. Global inorganic nitrate production mechanisms: comparison of a global model with nitrate isotope observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 3859–3877. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-3859-2020 (2020).

Hastings, M. G., Steig, E. J. & Sigman, D. M. Seasonal variations in N and O isotopes of nitrate in snow at summit, Greenland: implications for the study of nitrate in snow and ice cores. J. Geophys. Res. : Atmos. 109, 4123. https://doi.org/10.1029/2004JD004991 (2004).

Yun, H. et al. Nitrate formation from heterogeneous uptake of dinitrogen pentoxide during a severe winter haze in Southern China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 17515–17527. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-17515-2018 (2018).

Lorette, G. et al. Tracing sources and fate of nitrate in multilayered karstic hydrogeological catchments using natural stable isotopic composition (δ15N-NO3 – and δ18O-NO3–). Application to the Toulon karst system (Dordogne, France). J. Hydrol. 610, 127972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2022.127972 (2022).

Song, W. et al. Nitrogen isotope differences between atmospheric nitrate and corresponding nitrogen oxides: a new constraint using oxygen isotopes. Sci. Total Environ. 701, 134515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134515 (2020).

Zong, Z. et al. First assessment of NOX sources at a regional background site in North China using isotopic analysis linked with modeling. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 5923–5931. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b06316 (2017).

Fan, M. Y. et al. Changes of emission sources to nitrate aerosols in Beijing after the clean air actions: evidence from dual isotope compositions. J. Geophys. Res. : Atmos. 125, 8965. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JD031998 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. The isotopic characteristics, sources, and formation pathways of atmospheric sulfate and nitrate in the South China sea. Sustainability 16, 8733. http://doi.org/10.3390/su16208733 (2024).

Walters, W. W., Goodwin, S. R. & Michalski, G. Nitrogen Stable Isotope Composition (δ 15 N) of Vehicle-Emitted NO . Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 2278–2285. https://doi.org/10.1021/es505580v (2015).

Felix, J. D., Elliott, E. M. & Shaw, S. L. Nitrogen isotopic composition of Coal-Fired power plant nox: influence of emission controls and implications for global emission inventories. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 3528–3535. https://doi.org/10.1021/es203355v (2012).

Shi, Y. et al. Stable nitrogen isotope composition of NOX of biomass burning in China. Sci. Total Environ. 803, 149857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149857 (2022).

Felix, J. D. & Elliott, E. M. Isotopic composition of passively collected nitrogen dioxide emissions: vehicle, soil and livestock source signatures. Atmos. Environ. 92, 359–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.04.005 (2014).

Song, W. et al. Isotopic evaluation on relative contributions of major NOX sources to nitrate of PM2.5 in Beijing. Environ. Pollut. 248, 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2019.01.081 (2019).

Feng, X. et al. Impact of coal replacing project on atmospheric fine aerosol nitrate loading and formation pathways in urban Tianjin: insights from chemical composition and 15N and 18O isotope ratios. Sci. Total Environ. 708, 134797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134797 (2020).

Guha, T. et al. Isotopic ratios of nitrate in aerosol samples from Mt. Lulin, a high-altitude station in central Taiwan. Atmos. Environ. 154, 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2017.01.036 (2017).

Luo, L. et al. Assessment of the seasonal cycle of nitrate in PM2.5 using chemical compositions and stable nitrogen and oxygen isotopes at Nanchang, China. Atmos. Environ. 225, 117371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2020.117371 (2020).

Hastings, M. G., Sigman, D. M. & Lipschultz, F. Isotopic evidence for source changes of nitrate in rain at Bermuda. J. Geophys. Res. : Atmos. 108, 1145. https://doi.org/10.1029/2003JD003789 (2003).

Sigman, D. M. et al. A bacterial method for the nitrogen isotopic analysis of nitrate in seawater and freshwater. Anal. Chem. 73, 4145–4153. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac010088e (2001).

Parnell, A. C., Inger, R., Bearhop, S. & Jackson, A. L. Source partitioning using stable isotopes: coping with too much variation. PLoS One. 5, e9672. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0009672 (2010).

Zong, Z. et al. Dual-modelling-based source apportionment of NOX in five Chinese megacities: providing the isotopic footprint from 2013 to 2014. Environ. Int. 137, 105592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.105592 (2020).

Wang, Y. L. et al. Influences of atmospheric pollution on the contributions of major oxidation pathways to PM2.5 nitrate formation in Beijing. J. Geophys. Res. : Atmos. 124, 4174–4185. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JD030284 (2019).

Jin, Z. et al. Quantifying major NOX sources of aerosol nitrate in Hangzhou, China, by using stable isotopes and a bayesian isotope mixing model. Atmos. Environ. 244, 117979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2020.117979 (2021).

Xie, Y. et al. Nitrate-dominated PM2.5 and elevation of particle pH observed in urban Beijing during the winter of 2017. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 5019–5033. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-5019-2020 (2020).

Li, M. et al. Nonlinear responses of particulate nitrate to NOX emission controls in the megalopolises of China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 15135–15152. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-15135-2021 (2021).

Cai, S. et al. The impact of the air pollution prevention and control action plan on PM2.5 concentrations in Jing-Jin-Ji region during 2012–2020. Sci. Total Environ. 580, 197–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.11.188 (2017).

Zhang, Q. et al. Effects of meteorology and secondary particle formation on visibility during heavy haze events in Beijing, China. Sci. Total Environ. 502, 578–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.09.079 (2015).

Xu, Q. et al. Nitrate dominates the chemical composition of PM2.5 during haze event in Beijing, China. Sci. Total Environ. 689, 1293–1303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.06.294 (2019).

Li, H. et al. Case study of spring haze in Beijing: characteristics, formation processes, secondary transition, and regional transportation. Environ. Pollut. 242, 544–554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2018.07.001 (2018).

Kunlei, C. et al. Study and application of the isotopes N and O in nitrate determination by bacterial denitrification. J. Appl. Oceanogr. 40, 629–635. 10.3969/J.ISSN.2095-4972.2021.04.009 (2021).

Felix, J. D. & Elliott, E. M. The agricultural history of human-nitrogen interactions as recorded in ice core δ15N‐NO3. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 1642–1646. https://doi.org/10.1002/grl.50209 (2013).

Fibiger, D. L. & Hastings, M. G. First measurements of the nitrogen isotopic composition of NOX from biomass burning. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 11569–11574. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b03510 (2016).

Hastings, M. G., Jarvis, J. C. & Steig, E. J. Anthropogenic impacts on nitrogen isotopes of Ice-Core nitrate. Science 324, 1288–1288. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1170510 (2009).

Walters, W. W., Tharp, B. D., Fang, H., Kozak, B. J. & Michalski, G. Nitrogen isotope composition of thermally produced NOx from various Fossil-Fuel combustion sources. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 11363–11371. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b02769 (2015).

Li, D. & Wang, X. Nitrogen isotopic signature of soil-released nitric oxide (NO) after fertilizer application. Atmos. Environ. 42, 4747–4754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.01.042 (2008).

Li, T. et al. High contribution of anthropogenic combustion sources to atmospheric inorganic reactive nitrogen in South China evidenced by isotopes. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 23, 6395–6407. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-23-6395-2023 (2023).

An, Z. et al. Severe haze in Northern China: a synergy of anthropogenic emissions and atmospheric processes. Proc. Nat.l Acad. Sci. 116, 8657–8666. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1900125116 (2019).

Ansari, A. S. & Pandis, S. N. The effect of metastable equilibrium States on the partitioning of nitrate between the gas and aerosol phases. Atmos. Environ. 34, 157–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1352-2310(99)00242-3 (2000).

He, P. et al. The observation of isotopic compositions of atmospheric nitrate in Shanghai China and its implication for reactive nitrogen chemistry. Sci. Total Environ. 714, 136727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.136727 (2020).

Luo, L. et al. Fine particulate matter (PM2.5/PM1.0) in Beijing, China: variations and chemical compositions as well as sources. J. Environ. Sci. 121, 187–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2021.12.014 (2022).

Xiao, H. W. et al. Changes in the dominant contributions of nitrate formation and sources during haze episodes: insights from dual isotopic evidence. J. Geophys. Res. : Atmos. 130 https://doi.org/10.1029/2024JD042175 (2025).

Ji, X. et al. Nitrate pollution source apportionment, uncertainty and sensitivity analysis across a rural-urban river network based on δ15N/δ18O-NO3– isotopes and SIAR modeling. J. Hazard. Mater. 438, 129480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.129480 (2022).

Zhang, Q. et al. Drivers of improved PM2.5 air quality in China from 2013 to 2017. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 24463–24469. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1907956116 (2019).

Cheng, J. et al. Dominant role of emission reduction in PM2.5 air quality improvement in Beijing during 2013–2017: a model-based decomposition analysis. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 6125–6146. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-6125-2019 (2019).

Beijing Municipal Bureau of Statistics, Survey Office of the National Bureau of Statistics in Beijing. Beijing Statistical Yearbook 2023. (2023).

Li, X. & Yan, X. Fast penetration of electric vehicles in China cannot achieve steep cuts in air emissions from road transport without synchronized renewable electricity expansion. Energy 301, 131737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2024.131737 (2024).

Schnecker, J. et al. Seasonal dynamics of soil microbial growth, respiration, biomass, and carbon use efficiency in temperate soils. Geoderma 440, 116693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2023.116693 (2023).

Li, C. et al. Multi-pollutant emissions from the burning of major agricultural residues in China and the related health-economic effects. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 4957–4988. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-4957-2017 (2017).

Bäumer, D. et al. Relationship of visibility, aerosol optical thickness and aerosol size distribution in an ageing air mass over South-West Germany. Atmos. Environ. 42, 989–998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2007.10.017 (2008).

Deng, M., Wang, C., Yang, C., Li, X. & Cheng, H. Nitrogen and oxygen isotope characteristics, formation mechanism, and source apportionment of nitrate aerosols in Wuhan, central China. Sci. Total Environ. 921, 170715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.170715 (2024).

Huang, W. et al. Dual isotopic evidence of δ15N and δ18O for priority control of vehicle emissions in a megacity of East China: insight from measurements in summer and winter. Sci. Total Environ. 931, 172918. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.172918 (2024).

Wang, H. et al. Formation mechanism and control strategy for particulate nitrate in China. J. Environ. Sci. 123, 476–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2022.09.019 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Mutual promotion between aerosol particle liquid water and particulate nitrate enhancement leads to severe nitrate-dominated particulate matter pollution and low visibility. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 2161–2175. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-2161-2020 (2020).

Huang, X. et al. Chemical boundary layer and its impact on air pollution in Northern China. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 7, 826–832. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00755 (2020).

Gaston, C. J. & Thornton, J. A. Reacto-diffusive length of N2O5 in aqueous Sulfate- and Chloride-Containing aerosol particles. J. Phys. Chem. A. 120, 1039–1045. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.5b11914 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant numbers 12075261 and 12105311].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Z. and M.L. contributed to the conception and design of the study and the study protocol. S.Z. wrote this manuscript with input from all co-authors. M.L. and L.M. participated in the preparation as well as revision of the manuscript. Y.S. and D.X. were responsible for the revision and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhen, S., Luo, M., Shao, Y. et al. Study on the source of nitrate in atmospheric particulate matter in Beijing using nitrogen and oxygen dual isotopes. Sci Rep 15, 18174 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01179-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01179-9