Abstract

Craniofacial reconstruction and facial approximations are valuable resources in the fields of anthropometry, forensics and surgery. Their accuracy depends on the availability of population specific datasets and consistent research and focus on improving and updating these datasets over time. Our study focuses on bringing new normative data regarding the relationship between the upper lip and the upper anterior teeth in a sample of adult Western Romanian population. This retrospective study was conducted on 226 computed tomography scans from the existing patient database of the Emergency Municipal Hospital of Timisoara, being the first study of this kind to focus on the Romanian population. The patients were divided in six subgroups depending on age and sex. A total of ten landmarks were considered, eight in the frontal plane and two in the sagittal plane, five hard tissue and five soft tissue. The 3D Slicer free, open-source software was used for the analysis. The inter-landmark distances were measured and results were compared. The results of the present study show similar patterns of associations between the measured inter-landmark distances for men and women. According to the measurements, inter-landmark distances are larger in males, compared to females, in all age groups. The strong correlation between right and left inter-landmark distances demonstrates the obvious right-left symmetry of most cases. A positive association was found between the skeletal and soft tissue contour of the maxilla, specifically, between the upper anterior teeth and the upper lip.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The ability to reconstruct the human face has surgical, anthropological and forensic implications.

The first attempts of craniofacial reconstruction (CFR) and facial approximation (FA) date back to the years 1800, one of the pioneers in this field being Wilhelm His, with his famous reconstruction of Johann Sebastian Bach’s face1,2. The reconstruction methods became more complex and scientific over time, with significant contributions made by the Russian anthropologist Mikhail Gerasimov, whose method is now named after him3. Significant contributions were also made by Krogman, with what became known as the American method4. Later, the Manchester method combined these two together and is based on both soft tissue depth markers as well as on the layering of muscles and anatomical structures5.

It is common to estimate the orofacial characteristics based on the teeth6,7,8 and, from an orthodontic perspective, there is no doubt that the position of the lips is heavily influenced by the occlusion, more specifically by the incisor-canine relationship in the sagittal, vertical and transversal dimension9,10,11,12. In CFR it is important to acknowledge the fact that orthodontic pathologies, especially those of the anterior teeth, will affect the position of the lips. The facial appearance also is fundamentally modified if multiple teeth, especially upper anterior ones, are missing, as well as in cases of jaw bone pathology, either induced by trauma or deformation of various etiologies13,14,15.

In terms of technology and methods applied, the most comprehensive images are obtainable from Computed Tomography (CT), Cone-beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), which can render both the hard and the soft tissues in 3D, with great accuracy7,16. The limitations of these techniques are related to the dose of radiation used (in CT and CBCT), as well as to the cost, so most of the studies are retrospective ones, using preexisting databases17,18,19. Morphometric studies of the face have also made use of lateral cephalograms20,21, stereophotogrammetry22,23, laser scanners24 and, of course, direct measurements25,26,27.

It is generally accepted that ethnicity highly influences the morphology of facial features and the same applies to the lips and the oral region28,29,30,31. Therefore, the need for studies to collect normative data from various ethnic groups is obvious. So far, to the best of our knowledge, there is no data collection regarding the lip morphology of the Romanian population. The closest datasets that could be useful for this ethnic group would be those collected from other European populations, with similar ancestry.

According to the 2021 census, the Romanian population is considered quite homogeneous, stating that 89.3% of the people of Romania are ethnic Romanians32. However, variations of the facial features of populations among different regions within the same country have been reported29, so, we narrowed this first study to Western Romanian subjects, with future perspectives of broadening it at national level.

Some of the existing reports from literature state that inter-canine distance equals 75% of the total mouth width33, that interlimbus distance is a strong indicator of the width of the mouth6 and that the position of cheilion can be approximated based on the infraorbital foramen8.

The aim of this study is to explore and bring normative data regarding the anatomical region of the maxilla, focusing on the relationship between the upper lip and the anterior teeth in present day adult Western Romanian population, by assessing the relationship between ten hard and soft tissue landmarks. Besides its application in oral and maxillofacial surgery, the data collected in the present study could be relevant in cases of forensic and archaeological FA and CFR.

Materials and methods

The study was performed on CT scans of 226 individuals, 119 men and 107 women, all adult patients, retrieved from the database of the Emergency Municipal Hospital of Timisoara, Romania. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by The Ethics Committee of the “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy from Timisoara, Romania, document number 37/2021, and the IRB of the Emergency Municipal Hospital of Timisoara, Romania, document number E-5145/5.10.2021. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the IRB of the Emergency Municipal Hospital of Timisoara, Romania, waived the need of obtaining informed consent. The analyzed images consisted of records of previous patients of the hospital, so no patient was exposed to additional ionizing radiation for the purpose of this study. The scans were taken with a Definition Edge 64 slice (Siemens, Munich, Germany) and with a Somatom X-Cite 128 slice (Siemens, Munich, Germany).

The patients’ records were anonymized and divided into subgroups depending on age and sex. There were three age groups: 18–25 years old, 26–35 years old and 36–47 years old. The age group 18–25 years old consisted of 31 men and 37 women, the age group 26–35 years old consisted of 58 men and 41 women, while the 36–47 years old, consisted of 30 men and 29 women. The study was limited to the age of 47 due to the very large number of patients above this age that had compromised upper anterior teeth and therefore could not be included.

The inclusion criteria were adult patients, CT scans covering at least the maxillary region, upper and lower lip, the presence of at least upper central incisors and upper canines (with or without prosthodontic rehabilitation).

The exclusion criteria were: syndromes and trauma involving the midface, cleft lip or palate, swelling of the upper lip or the maxillary region, obvious cosmetic procedures (e.g. lip fillers), previous orthognathic surgery.

There were a total of ten landmarks taken into consideration, eight of these in the frontal plane and two in the sagittal plane, five hard tissue and five soft tissue landmarks, labeled as shown in Table 1. The craniofacial complex was orientated on the Frankfurt/Frankfort Horizontal Plane. Thirteen inter-landmark distances were measured (Table 2). All measurements were expressed in millimeters (mm). In order to assess the accuracy, the landmark placement and the measurements were repeated for 20% of the total sample. Intra-observer reliability was evaluated using the interclass correlation coefficient (ICC), with values exceeding 0.7 for all distance measurements except F2-F4, which had an ICC of 0.5.

The 3D Slicer 5.6.1 (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA) free, open-source software, one of the most widely used software products for medical image (obtained via CT, MRI, etc.) processing and visualization, was used for the analysis.

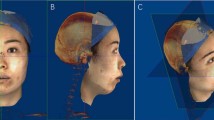

The landmarks were placed using the “Markups module” in 3D Slicer. The same order in placing the landmarks was kept for all patients by using the 3D Slicer “Volume Rendering” tool (Fig. 1). The preset CT-Bones was used for placing the hard tissue landmarks (Fig. 1a, c), while for the soft tissue the preset CT-Muscle was used (Fig. 1b, d). A copy of the cranium with already placed landmarks (Fig. 1e) was saved to a separate folder using the “Save Scene” tool (Fig. 1f). The control points were then exported to a specially made Excel file to measure the inter-landmark distances.

a Axial, coronal and sagittal views of the cranium in 3D Slicer software. Skeletal landmarks applied in coronal plane; b Axial, coronal and sagittal views of the cranium in 3D Slicer software. Soft tissue landmarks applied in coronal plane; c Axial, coronal and sagittal views of the cranium in 3D Slicer software. Skeletal landmarks applied in sagittal plane; d Axial, coronal and sagittal views of the cranium in 3D Slicer software. Soft tissue landmarks applied in sagittal plane; e Axial, coronal and sagittal view of the cranium in 3D Slicer software. Highlighted landmark coordinates; f “Save scene” protocol for each individual.

Associations between inter-landmark distances were examined visually using pairwise scatterplots. As no nonlinear relationships were found, the strength of associations was evaluated by means of the Pearson correlation coefficient r.

Next, the distributions of inter-landmark distances were compared between men and women, as well as among age groups in both sexes. To account for the correlation structure in the dependent variables, a multivariate approach was adopted, using multivariate Kruskal-Wallis tests34. This nonparametric method was selected due to several factors: the absence of multivariate normality within groups, as determined by multivariate Shapiro-Wilk tests, the lack of homogeneity in variance-covariance matrices across groups, confirmed by Box’s M-tests, and the presence of multivariate outliers in the dependent variables, identified using Mahalanobis distances. The multivariate Kruskal-Wallis test simultaneously evaluates distributional differences across multiple dependent variables. Thus, when significant differences were detected, post-hoc univariate Kruskal-Wallis tests were conducted to provide variable-specific insights. To control for the risk of errors due to multiple comparisons, p-values were adjusted using the Bonferroni correction. P-values less than 0.01 were considered as statistically significant.

All the statistical analyses were conducted in R, version 4.3.1.

Results

Table 3 shows the summary statistics for inter-landmark distances measured for the entire study group (men+women), whereas Table 4 shows the summary statistics for inter-landmark distances by sex and adjusted p-values of univariate Kruskal-Wallis tests for comparisons between sexes.

Table5 presents the p-values of the Shapiro-Wilk tests assessing multivariate normality within groups defined by sex and age.

The correlation analysis revealed similar patterns of association between distances for the two sexes (Fig. 2a and b). The strongest linear associations were found between the distances F1-F5 and F2-F6 (r = 0.90 for both men and women), F2-F4 and F3-F4 (women: r = 0.77; men: r = 0.83), F1-F3 and F3-F4 (women: r = 0.69; men: r = 0.85), F5-F7 and F7-F8 (women: r = 0.75; men: r = 0.69), F5-F7 and F6-F8 (women: r = 0.72; men: r = 0.69), F6-F8 and F7-F8 (women: r = 0.65; men: r = 0.72). Notably, for male subjects, the distances F1-F3 and F2-F4 were also strongly associated (r = 0.69), whereas for females this correlation is weaker (r = 0.42). A less strong association, but worth mentioning, was found between upper canine right-left F3-F4 and cheilion right-left F7-F8 landmarks: women: r = 0.30; men: r = 0.36. No other significant associations were found between hard tissue-hard tissue and soft tissue-soft tissue landmarks, which points out the practical importance of available average measurements databases.

Significant differences were observed in the joint distributions of inter-landmark distances between men and women (multivariate Kruskal-Wallis test, p < 0.001). Subsequent univariate analyses revealed significant sex-based differences for all individual variables (univariate Kruskal-Wallis tests, p < 0.01 in all cases), with women generally exhibiting smaller distances (Table 4).

Within each subpopulation, no statistically significant differences were detected among age groups (multivariate Kruskal-Wallis tests, p = 0.096 for men and 0.071 for women). Comparisons of inter-landmark distances by sex and age group can be visualized in Fig. 3a-m.

Discussion

Worldwide studies regarding estimating the mouth and face from the skull, specifically for forensic purposes are currently available. However, data on how hard and soft tissue features spatially relate in the mouth region is still limited35. Traditionally, FA have relied on linear measurements and ratios, later on evolving to computerized methods36,37.

The first detailed studies of the lips and mouth were performed by Farkas et al., who undertook extensive measurements of the North American White population (NAW), since, at that time (late XX century), no normative data regarding craniofacial dimensions of NAW were available38. Farkas spent much of his career measuring faces, compiling a huge database of norms and modernizing craniofacial anthropometry39. He didn’t limit his studies to NAW, but undertook investigations on several population groups across Europe, Middle East, African-Americans, using large samples of individuals, of different ages40,41,42,43.

Some of the classic guidelines in reconstructing the mouth are due to Krogman and Iscan44, stating that the corners of the mouth should be positioned on radiating lines from the canine-first premolar junction.

Wilkinson brought a further addition to this rule and stated that the cheilion should be placed on “reference lines that radiate from the canines at a 90 degree angle from the dental arch” and that only in this case this guideline is applicable6. Regarding Wilkinson’s addition to the cheilion position, this was found to be inaccurate by Stephen and Murphy’s research8.

Wilkinson et al. studied the position of the cheilion relative to the eyes and the thickness of the upper lip relative to the upper incisors, performing manual measurement on a sample of 96 subjects (men and women) of White European and Asian Indian ethnicity. Positive correlations between the inter-limbus (the distance between the medial borders of the iris) distance, the inter-pupillary distances and the inter-cheilion distance were reported, with the inter-limbus distance being considered the most reliable method for mouth width approximation. Regarding the lip height, positive correlations between the lip height and the height of the incisors, in both women and men, for both White European and Asian Indian individuals, were reported. However, Asian Indian individuals displayed thicker lips, suggesting that not only individual and gender but ethnic variations need to be acknowledged6.

A frequently used guideline for FA belongs to Stephan and Henneberg, stating that the inter-canine distance represents 75% of the total mouth width (inter-cheilion distance), was demonstrated to be accurate33, and further confirmed by Stephan and Murphy, when comparing it to other FA methods. They concluded that the 75% rule should be considered the first choice whenever dentition is present8,45. In a study on 9 embalmed cadavers, Stephan and Murphy also stated that, in case of edentulous skulls, the mouth width can be correctly determined from non-dental landmarks, such as the inter infraorbital foramina or mental foramina distances8.

The results of the present study show linear associations between the measured inter-landmark distances. The positive correlation between right and left inter-landmark distances (F1-F3/F2-F4, F3-F4/F7-F8, F5-F7/F6-F8, F1-F5/F2-F6), demonstrates the obvious right-left symmetry of most cases (Fig. 2). The relationship between the mean measured values of inter-canine distance (F3-F4) and inter-cheilion distance (F7-F8) is in line with Stephan’s 75% rule8,33, both in men (73.16%) and women (75.09%), as well as when the entire study group (74.04%) is considered, the association being obviously stronger in women (Table 3).

The age and sex specific boxplots (Fig. 3) serve as visual guide and demonstrate the relationship of the specific inter-landmark distances with age and sex, women exhibiting smaller distances for all measurements (Table 4). These findings are coincident with the results previously reported in other studies35,46.

In 2022, Houlton et al. investigated the teeth-mouth relationship and variation in 147 South African Black and White individuals, aged 20–75 and reported age-related changes in the soft and hard tissue of the mouth, including gradual widening of the mouth with age, which is in line with our measurements, which show a certain F7-F8 inter-landmark distance increase with age (Fig. 3f). Houlton’s retrospective study is a morphometric analysis which used 20 landmarks, performed on CBCT datasets, avoiding the shortcomings that cadaver studies inherently have, such as postmortem dehydration and deformation and supine position. They also bring new data regarding the Cupid bow, which was found to flatten and widen with age, due to lip elongation and lip vermillion decrease. This study emphasizes once again that the proportions of the mouth are not only impacted by age, and sex, but by ethnic variations as well35.

Sforza et al. digitally assessed the relations between facial landmarks, using a large sample of 918 healthy white Italians aged 4–73 years. According to their measurements, at any age, labial volume, lip area and lip height were larger in men than in women. The mouth width was found to increase with age, once more in line with our measurements of F7-F8 (Fig. 3f). The philtrum width, and presumably the Cupid bow dimensions as well, showed a significant sexual dimorphism and increased with age, but the age-related modifications in philtrum width were more scattered46. According to our measurements, the Cupid bow width (F5-F6) tends to increase with age (Fig. 3e).

The distance between hard and soft tissue points A and A’, of utmost importance for approximating the depth of the oral philtrum in facial reconstruction, was also found to be higher in men compared to women (Fig. 3g), meaning that men have thicker upper lips. Our findings are in line with Ferrario et al., who aimed to evaluate labial morphology and to assess gender-related differences based on dental and lip impressions of 11 men and 10 women aged 21 to 34 years, with sound, full, permanent dentition. The models obtained were digitized, and the labial volume was measured using the 3D models, thus concluding that the labial thickness was larger in the men than in women47.

According to Fig. 3g, a certain age related philtrum thickening tendency may also be observed, which is not so obvious, but visible. It should be noted that the oldest individual included in our study is 47 years old, compared to over 70 in Houlton’s and Sforza’s studies35,46.

The present study was carried out on adult individuals, aged 18–47, as many CT scans belonging to patients above this age showed compromised upper anterior teeth and therefore could not be included, one of the inclusion criteria being the presence of at least upper central incisors and upper canines (with or without prosthodontic rehabilitation).

Aging of the perioral region plays an important role in the general facial appearance and is therefore important in FR as well. It’s very difficult, if not impossible to estimate the aging skin aspect from the skull alone. Fine wrinkles, deep nasolabial or labiomental folds, elongation and flattening of the upper lip, reduced vermillion size, downturned corners of the mouth, chin irregularities and reduced show of upper teeth are some of the quantifiable parameters of the aging mouth. These are all features that should be visible in FR of an aged skull. The severity of these processes and the individual variability, however, is difficult to estimate48.

Usually, it’s assumed that the severity of these parameters is directly proportional with the biological age, which can be estimated from the skull. However, the degree of facial changes related to age is highly impacted by multiple factors, so general FA rules should be applied, according to the estimated age.

According to the scientific literature, the age related decrease of the vermillion height, considered a stigma of the aging face, can be detected in different ethnic groups, like Chinese women in Chong’s et al. study49 or Caucasian women, as per Doll et al.50 and Sforza et al.46. Chong et al. also found that the lip width significantly increases with age49, in line with the present study, as, according to our measurements, F7-F8 appears to increase with age, in both sexes (Fig. 3f).

Because of the close proximity of the lips to the alveolar bone and the teeth, it is reasonable to assume that the underlying hard tissue will have an impact on the covering soft tissue and that there is a certain analogy between the morphology and position of the adjacent structures. This idea is supported by our measurements, which emphasize the relationship between hard tissue and soft tissue landmarks (Fig. 3g, h,i, l,m).

According to the literature, edentulous skulls or skulls missing multiple teeth exhibit different facial features compared with skulls having complete dentition. If only one or a few teeth are missing from the lateral parts of the jaw, this will not severely impact the face, but lack of several teeth produce consecutive changes which are ultimately visible in the face. The reduced vertical dimension of the lower third of the face usually causes increased sagging of the cheeks, downturned cheilion and increased labiomental or nasolabial folds. The cheeks and lips may be inwardly collapsed. Missing anterior teeth, especially in the upper arch, has a strong visual impact and causes soft tissue changes as collapsed lips, with reduced vermillion, as the lips lack support51.

Skomina et al. have investigated the facial changes in 90 edentulous and non-edentulous individuals, by means of 3D facial scans and reported that the width of the mouth, the facial height, lip vermilion are significantly reduced in the edentulous group52. According to their assessment, ageing has no impact on the width of the mouth, but tooth loss does, as edentulous participants had narrower mouths. Sex dimorphism was observed for this parameter, with men having wider mouths than women36, in line with our study. However, their findings regarding the fact that ageing doesn’t affect the mouth width are in contradiction with ours.

Another interesting morphometric analysis of the upper lip, based on 3D scans, undertaken by Hao et al. on 25 edentulous patients, gives an extensive description of the changes that occur in the perioral region after the insertion of dental implants and prosthetic restorations, concluding that the implant supported dentures have elevated and stretched the lips, and that the mouth width increased after prosthetic rehabilitation53. Conversely, this gives us an idea of how to estimate the missing teeth impact on the facial appearance, when performing a CFR.

Yuan et al. aimed to create a virtual method of predicting esthetic changes based on 3D scans of 10 edentulous patients, before and after wearing dentures. This is another example of facial 3D scan application in the dental field. In their study, the method was used to predict the patient’s post-restoration facial appearance and visualize it prior to performing restoration54.

The shortcomings identified in our study are, first of all, the relatively small sample size, limited by available CT scans, and the supine position of the subjects, characteristic for the CT scans, that may have influenced, to a small extent, the shape of the lips or the position of cheilion. Furthermore, the patients were not instructed to maintain a natural relaxed lip position, as this is a retrospective study carried out on already available CT scans, collected from the hospital’s database. The fact that the landmark placement and the measurements were performed by a single experienced scientist, despite the fact that they were repeated for 20% of the total sample, in order to assess accuracy, is to be mentioned as a limitation of this study.

However, being the first study to investigate the maxillary region of Romanian subjects, it is our strong belief that it will constitute a valuable addition to existing anthropometric databases of the European population. The data collected could serve as the first database for the description of the upper lip morphology in adult Western Romanian population, also considering sex-related variations, with potential forensic and anthropometrical application, such as FA and CFR. It is our future goal to further extent this study nationally, on larger population samples, and to refine the quality of the findings by using alternative investigation methods (besides preexisting CTs).

Conclusions

Within the limitations of this study, the main conclusions are as follows:

All inter-landmark distances are larger in men, compared to women.

The correlation analysis revealed similar patterns of association between inter-landmark distances for both sexes.

A positive association was found between the skeletal and soft tissue contour of the maxilla, specifically, between the upper anterior teeth and the upper lip.

This data can be useful in CFR and FA, but extended research, based on a larger sample size, is needed to refine the data.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Beasley, W. Bach and his. ANZ J. Surg. 84, 910–914. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.12398 (2014).

Zegers, R. H. C., Maas, M., Koopman, A. G. & Maat, G. J. R. Are the alleged remains of Johann Sebastian Bach authentic? Med. J. Aust. 190, 213–216. https://doi.org/10.5694/J.1326-5377.2009.TB02354.X (2009).

Ullrich, H. & Stephan, C. N. On Gerasimov’s plastic facial reconstruction technique: new insights to facilitate repeatability. J. Forensic Sci. 56, 470–474. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1556-4029.2010.01672.X (2011).

De Buhan, M. & Nardoni, C. A facial reconstruction method based on new mesh deformation techniques. Forensic Sci. Res. 3, 256–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/20961790.2018.1469185 (2018).

Vanezis, M. & Vanezis, P. Cranio-facial reconstruction in forensic identification-historical development and a review of current practice. Med. Sci. Law. 40, 197–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/002580240004000303 (2000).

Wilkinson, C. M., Motwani, M. & Chiang, E. The relationship between the soft tissues and the skeletal detail of the mouth. J. Forensic Sci. 48, 2002412. https://doi.org/10.1520/jfs2002412 (2003).

Sforza, C., De Menezes, M. & Ferrario, V. F. Soft-and hard-tissue facial anthropometry in three dimensions: what’s new. JASs Invit Rev. J. Anthropol. Sci. 91, 159–184. https://doi.org/10.4436/JASS.91007 (2013).

Stephan, C. N. & Murphy, S. J. Mouth width prediction in craniofacial identification: cadaver tests of four recent methods, including two techniques for edentulous skulls. J. Forensic Odontostomatol. 27, 2–7 (2008).

Toma, A. M. et al. The assessment of facial variation in 4747 British school children. Eur. J. Orthod. 34, 655–664. https://doi.org/10.1093/EJO/CJR106 (2012).

Kuhn, M. et al. Effect of different incisor movements on the soft tissue profile measured in reference to a rough-surfaced palatal implant. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 149, 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2015.08.017 (2016).

Hayashida, H., Ioi, H., Nakata, S., Takahashi, I. & Counts, A. L. Effects of Retraction of anterior teeth and initial soft tissue variables on lip changes in Japanese adults. Eur. J. Orthod. 33, 419–426. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjq095 (2011).

Faysal Talass, M., Tollaae, L. & Baker, R. C. Soft-tissue profile changes resulting from Retraction of maxillary incisors. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 91, 385–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/0889-5406(87)90391-X (1987).

Kukuła, K. & Plakwicz, P. Oral pathology: exostosis deforming face features. Br. Dent. J. 221, 50–51. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.514 (2016).

Motoyasu, H. et al. Changes in facial appearance alter one’s sensitivity not only to the self but also to the outside world. Front. Psychol. 15, 1426820. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1426820 (2024).

Skomina, Z., Kuhar, M. & Verdenik, M. Ihan Hren, N. Stereophotometric facial changes in edentulous older adults after rehabilitation with complete dentures. Gerodontology 00, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/ger.12774 (2024).

Zhao, J. M. et al. Lip morphology Estimation models based on three-dimensional images in a modern adult population from China. Int. J. Legal Med. 135, 1887–1901. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00414-021-02559-2 (2021).

Wang, B., Dong, Y., Zhao, Y., Bai, S. & Wu, G. Computed tomography measurement of the auricle in Han population of North China. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 64, 34–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2010.03.053 (2011).

Aljarrah, K., Packirisamy, V., Al Anazi, N. & Nayak, S. B. Morphometric analysis of foramen magnum and occipital condyle using CT images for sex determination in a Saudi Arabian population. Morphologie 106, 260–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.morpho.2021.07.006 (2022).

Bahsi, I., Orhan, M., Kervancioglu, P. & Yalcın, E. D. Morphometric evaluation and clinical implications of the greater palatine foramen, greater palatine Canal and pterygopalatine fossa on CBCT images and review of literature. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 41, 551–567. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00276-019-02179-x (2019).

Sazgar, T., Al-Jaf, N., Norman, N. & Alias, A. A geometric morphometric evaluation of facial hard tissue patterns. J. Orthod. Sci. 11, 24–32. https://doi.org/10.4103/JOS.JOS_199_21 (2022).

Knigge, R. P. et al. Geometric morphometric analysis of growth patterns among facial types. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 160, 430–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2020.04.038 (2021).

Bohringer, S. & de Jong, M. A. Quantification of facial traits. Front. Genet. 10, 10:397. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2019.00397 (2019).

Ambrosio, E. C. P. et al. Longitudinal morphometric analysis of dental arch of children with cleft lip and palate: 3D stereophotogrammetry study. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 126, 463–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oooo.2018.08.012 (2018).

Bannister, J. J. et al. Fully automatic landmarking of syndromic 3D facial surface scans using 2D images. Sensors 20, 3171 (2020), https://doi.org/10.3390/s20113171

Farkas, L. G., Hreczko, T. M., Katic, M. J. & Forrest, C. R. Proportion indices in the craniofacial regions of 284 healthy North American white children between 1 and 5 years of age. J. Craniofac. Surg. 14, 13–28. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001665-200301000-00004 (2003).

Amini, F., Mashayekhi, Z., Rahimi, H. & Morad, G. Craniofacial morphologic parameters in a Persian population: An anthropometric study. J. Craniofac. Surg. 25, 1874–1881 2014, (2014). https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0000000000000902

Salah, M., Higzi, M. A. I., Ali, R. W. & Naini, F. B. The Sudanese female face: normative craniofacial measurements and comparison with African-American and North American white females. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 42, 1704–1709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2014.06.003 (2014).

Vitosyte, M. et al. Lip morphometry and morphologic pattern variation by ethnicity. Anthropol. Anzeiger. 80, 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1127/anthranz/2022/1598 (2023).

Goel, A., Patnaik, V. & Puri, N. Lip morphometry in 600 North Indian adults: a data base study for sexual dimorphism. Med. Sci. Law. 55, 16–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0025802414524382 (2015).

Bahsi, I. et al. Lip anthropometry of healthy Turkish young adults. J. Craniofac. Surg. 33, 696–700. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0000000000008006 (2022).

Bulut, O., Sipahioglu, S. & Hekimoglu, B. Facial soft tissue thickness database for craniofacial reconstruction in the Turkish adult population. Forensic Sci. Int. 242, 44–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FORSCIINT.2014.06.012 (2014).

Guvernul României/Departamentul pentru Relații Interetnice. https://dri.gov.ro/w/institutul-national-de-statistica-a-publicat-datele-provizorii-ale-recensamantului-populatiei-si-locuintelor-2021/ (accessed 19.03.2025).

Stephan, C. N. & Henneberg, M. Predicting mouth width from inter-canine width-a 75% rule. J. Forensic Sci. 48, 725–727 (2003).

He, F. et al. Non-parametric MANOVA approaches for non-normal multivariate outcomes with missing values. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods. 46, 7188–7200. https://doi.org/10.1080/03610926.2016.1146767 (2017).

Houlton, T. M. R., Jooste, N., Steyn, M. & Hemingway, J. Visualising trends in dentition to lip mouth morphology using geometric morphometrics. PLoS One. 17, e0274127. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274127 (2022).

Blau, S. & Ubelaker, D. H. (eds) Handbook of Forensic Anthropology and Archaeology (2nd edition), 1–738 Routledge, (2016). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315528939

Shui, W., Wu, X. & Zhou, M. A computerized facial approximation method for Homo sapiens based on facial soft tissue thickness depths and geometric morphometrics. J. Anat. 243,796–812 (2023). (2023). https://doi.org/10.1111/joa.13920

Naini, F. B., Leslie, G. & Farkas Arch. Facial Plast. Surg. 12, 141–142 doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/archfacial.2010.29. (2010).

Farkas, L. G., Hreczko, T. A., Kolar, J. C. & Munro, I. R. Vertical and horizontal proportions of the face in young adult North American Caucasians: revision of neoclassical canons. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 75, 328–338. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-198503000-00005 (1985).

Farkas, L. G., Katic, M. J. & Forrest, C. R. International anthropometric study of facial morphology in various ethnic groups/races. J. Craniofac. Surg. 16, 615–646. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.scs.0000171847.58031.9e (2005).

Farkas, L., Forrest, C. & Litsas, L. Revision of neoclassical facial canons in young adult Afro-Americans. Aesth Plast. Surg. 24, 179–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002660010029 (2000).

Le, T. T., Farkas, L. G., Ngim, R. C. K., Levin, L. S. & Forrest, C. R. Proportionality in Asian and North American Caucasian faces using neoclassical facial canons as criteria. Aesth Plast. Surg. 26, 64–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-001-0033-7 (2002).

Farkas, L. G., Katic, M. J. & Forrest, C. R. Comparison of craniofacial measurements of young adult African-American and North American white males and females. Ann. Plast. Surg. 59, 692–698. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sap.0000258954.55068.b4 (2007).

Krogman, W. M. & Iscan, M. Y. The Human Skeleton in Forensic Medicine 2nd edn (C.C. Thomas Pub. LTD, 1986).

Stephan, C. N. Facial approximation: an evaluation of mouth-width determination. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 121, 48–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/AJPA.10166 (2003).

Sforza, C. et al. Age- and sex-related changes in three-dimensional lip morphology. Forensic Sci. Int. 200 182.e1-182.e7 (2010).

Ferrario, V. F., Rosati, R., Peretta, R., Dellavia, C. & Sforza, C. Labial morphology: A 3-dimensional anthropometric study. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 67, 1832–1839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2009.04.080 (2009).

Fink, B., Campiche, R., Shackelford, T. K. & Voegeli, R. Age-dependent changes in skin features and perceived facial appearance in women of five ethnic groups. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 46, 1017–1034. https://doi.org/10.1111/ics.13003 (2024).

Chong, Y. et al. Stereophotogrammetry to reveal age-related changes of labial morphology among Chinese women aging from 20 to 60. Skin. Res. Technol. 27, 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/SRT.12906 (2021).

Doll, C. et al. Age-related changes of the orolabial region in Caucasian women: an anthropometric analysis. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 74, 2497–2503. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JOMS.2016.08.007 (2016).

Morera Serna, E., Serna Benbassat, M., Terré Falcón, R. & Murillo Martín, J. Anatomy and aging of the perioral region. Facial Plast. Surg. 37, 176–193. https://doi.org/10.1055/S-0041-1725104/ID/JR200289OA-15/BIB (2021).

Skomina, Z., Kočevar, D., Verdenik, M. & Hren, N. I. Older adults facial characteristics compared to young adults in correlation with Edentulism: a cross sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 22 https://doi.org/10.1186/S12877-022-03190-5 (2022).

Hao, K., Luo, J., Di, P., Zhang, Y. & Lin, Y. Morphometry and displacement analysis of the upper lips following maxillary full-arch implant-supported fixed prostheses: a 3D morphometric study. BMC Oral Health. 21, 461. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-021-01838-z (2020).

Yuan, F., Cheng, C., Dai, N. & Sun, Y. Prediction of aesthetic reconstruction effects in edentulous patients. Sci. Rep. 7, 18077. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-017-17065-Y (2017).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge VICTOR BABES UNIVERSITY OF MEDICINE AND PHARMACY TIMISOARA for their support in covering the costs of publication for this research paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.C.R., L.B. and L.C.A. defined the research goals and coordinated the research, L.B., K.N., and O.B. developed the methodology, L.B. and F.I. performed the measurements, L.C.A., C.Z. and L.B. wrote the manuscript, K.N. and C.Z. analyzed the data, L.C.R. and L.C.A. synthetized and interpreted the results, L.B preserved the data. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rusu, L.C., Beschiu, L.M., Iacob, F. et al. A morphometric anthropometric analysis of the upper lip in adult Western Romanian population- a retrospective study. Sci Rep 15, 18487 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01204-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01204-x