Abstract

Fracturing flowback fluid, which is the waste fluid generated following the hydraulic fracturing of oil wells, has garnered significant attention in recent years regarding its safe treatment technologies. Low-temperature plasma water treatment technology is particularly notable for its high degradation efficiency and the environmentally benign by-products it produces. This study represents the inaugural application of dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasma for the degradation of fracturing flowback fluid. The research investigates the influence of varying voltages and initial pH on degradation efficiency, chemical oxygen demand (COD), pH, and viscosity of the flowback fluid. Furthermore, the mechanism of DBD plasma degradation of fracturing flowback fluid has been proposed. The findings indicate that the optimal parameters for DBD plasma degradation are as follows: a discharge voltage of 18 kV, a frequency of 10 kHz, a discharge duration of 120 min, and an initial solution pH of 7. Under these specified conditions, the degradation efficiency and COD of the flowback fluid were determined to be 71.41% and 104.00 mg/L, respectively. These results suggest that the degradation of fracturing flowback fluid via DBD plasma is a viable approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hydraulic fracturing represents a significant technique employed to enhance oil production. This process involves the injection of fracturing fluid, which transmits the high pressure generated by surface equipment to the geological formation, resulting in the fracturing of the formation. Concurrently, proppant is transported through the fracture to prevent its closure upon cessation of pumping. Once the proppant occupies the fracture, the seepage area is expanded, flow resistance is diminished, and the objective of well stimulation is accomplished. In hydraulic fracturing operations, each well typically receives between 2 and 7 million gallons of fracturing fluid, with approximately 10–40% of this volume returning to the surface as flowback fluid1. This flowback fluid constitutes one of the most substantial waste streams produced during oil and gas exploration and extraction2. The primary constituents of frac flowback fluid include organic matter, suspended solids (SS), and metals3. Due to its elevated chemical oxygen demand (COD), total suspended solids (TSS), total dissolved solids (TDS), as well as its stability and toxicity, flowback fluid cannot be discharged directly into the environment4,5. Conventional treatment methods for fracturing flowback fluid are categorized into chemical, physical, and biological approaches. Advanced oxidation technology has emerged as a prevalent chemical approach for the treatment of fracturing flowback fluid in recent years, demonstrating efficacy in the removal of organic matter and chemical oxygen demand (COD) from such fluids. This technology is often employed in conjunction with other treatment methods, resulting in a complex treatment process. For instance, Han et al. utilized ferrate, characterized by its high redox potential, to treat fracturing flowback fluid, achieving a total COD removal rate of 74.2% post-treatment6. Similarly, Wang et al. implemented the homogeneous sono-Fenton process for the treatment of fracturing flowback fluid, attaining a COD removal rate of 81.15% under optimal conditions.However, this method necessitated multiple adjustments of pH and careful temperature monitoring7. Additionally, physical treatment methods for fracturing flowback fluid primarily encompass precipitation and filtration techniques, which are employed to eliminate suspended solids, oil, and other contaminants present in the wastewater. Ren et al.8 developed a combined process utilizing ceramic membrane-electrodialysis hybrid (ED-H/L) and pressure reverse osmosis (RO) for the treatment of fracturing flowback fluid. Their findings indicated that the coagulation-ceramic membrane approach achieved removal efficiencies of total dissolved solids (TDS) and chemical oxygen demand (COD) of 97.5% and 31.9%, respectively. In recent years, various membrane technologies, including smart and composite membranes, have been introduced for the separation of oil and water in flowback fluid applications9,10. Regarding biological treatment methods, bioreactors have demonstrated efficacy in treating fracturing flowback fluid11. However, the high TDS concentration in such fluids poses significant challenges to the effective operation of biological treatment systems12. Additionally, biofilms have been employed in treatment systems for fracturing flowback fluid, although they typically require extended processing times. For instance, Freedman et al. incorporated biofilm into their experimental filtration system and reported a COD removal rate of 78.6% after 167 h of operation13. Given the limitations associated with these traditional treatment technologies, there is an urgent need for the development of efficient, rapid, cost-effective, and environmentally sustainable methods for the treatment of fracturing flowback fluid.

Plasma is recognized as the fourth state of matter. It consists of a mixture of excited molecules and atoms, electrons, photons, ions, and uncharged neutral particles, typically maintaining an electrically neutral condition14. Plasma can be categorized into high-temperature and low-temperature varieties based on the thermal differences among electrons, ions, and gas molecules15. In contrast to high-temperature plasma, low-temperature plasma is characterized as a partially ionized gas, with temperatures generally approximating room temperature16. This characteristic mitigates issues related to equipment wear17. Furthermore, low-temperature plasma operates effectively under standard temperature and pressure conditions, offering advantages such as ease of operation, cost-effectiveness, and environmental sustainability. In recent years, the applications of low-temperature plasma have expanded significantly across various fields, including medicine and industry18,19,20.

Low-temperature plasma water treatment technology represents a novel advanced oxidation method that integrates various mechanisms, including active free radical oxidation, ozone oxidation, ultraviolet radiation, and shock wave action. This technology primarily utilizes hydroxyl free radicals and other reactive species to facilitate the degradation of organic contaminants in water21. Its non-selective nature and lack of secondary pollution make it a widely adopted approach in sewage treatment applications22. Currently, dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasma is a prevalent form of low-temperature plasma employed for wastewater treatment, characterized by its straightforward operation, substantial processing capacity, and high efficiency23. Research conducted by Karoui et al. demonstrated that the synergistic application of DBD plasma and photocatalysis significantly enhanced the degradation efficiency and mineralization rate of ciprofloxacin24. Similarly, Zhang et al. reported that the combination of DBD plasma with CaO2 markedly improved the degradation of sulfamethoxazole in sludge, indicating its considerable potential for decontamination purposes25. Huang et al. found that the degradation efficiency of norfloxacin in wastewater was increased by 14.1% when DBD plasma was used in conjunction with cobalt carbon composite, compared to the application of DBD plasma alone26. Furthermore, Han et al. utilized DBD plasma alongside graphene (rGO)-WO3 nanocomposites to co-degrade dimethyl phthalate (DMP), revealing that the incorporation of RGO-WO3 enhanced the degradation performance of the DBD plasma system27. Lu et al. observed that the removal rate of the azo dye OG using a low-temperature plasma complex with Fe2+ was significantly superior to that achieved with a standalone DBD plasma system28. Additionally, the application of DBD plasma in the treatment of polymer-containing wastewater resulted in the degradation of polyacrylamide molecular chains, leading to a reduction in solution viscosity29. In conclusion, DBD plasma technology has demonstrated remarkable efficacy in organic degradation within water treatment processes, particularly in terms of viscosity reduction and degradation efficiency.

Based on the effective application of DBD plasma in the treatment of industrial wastewater, this study represents the inaugural use of DBD plasma for the degradation of fracturing flowback fluid. The research investigates the effects of varying voltage levels and initial solution pH on the degradation of fracturing flowback fluid, aiming to identify optimal process parameters. Additionally, infrared characterization analyses of the solution were conducted both prior to and following the degradation process. A proposed mechanism for the DBD plasma degradation of fracturing flowback fluid is presented, offering a novel approach for the environmentally sustainable treatment of such fluids.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Main chemicals required for the experiment: Anthrone (C14H10O; 98%) was purchased from Tianjin Huasheng Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Sodium hydroxide (NaOH; 96%) was purchased from Tianjin Fengchuan Chemical Reagent Technology Co., Ltd. Potassium bromide (KBr; 99%) was purchased from Tianjin Aijianda Technology Development Co., Ltd. Sulfuric acid (H2SO4; 98%) and hydrochloric acid (HCl; 98%) were purchased from Maoming Xiongda Chemical Co., Ltd. Deuterated chloroform (CDCl₃, 98%) was purchased from Ningbo Cuoying Chemical Technology Co., Ltd. Isopropyl alcohol (10 mM) was purchased from Guangdong Daxing Technology Co., Ltd. 1,4-Benzoquinone (10 mM) was purchased from Guangdong Testing Technology Co., Ltd. Hydroxypropyl guar gum was purchased from Renqiu Pengyu Chemical Co., Ltd. COD prefabricated reagent was purchased from Hash Corporation.

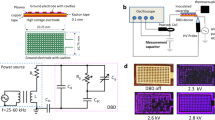

DBD plasma system

The DBD plasma system described in this study is illustrated in Fig. 1. The experimental setup utilized an alternating current high voltage power supply (CTP-2000 K, Nanjing Suman Electronics Co., Ltd.), operating at a central frequency of 10 kHz. The quartz DBD reactor (DBD 50, Nanjing Suman Electronics Co., Ltd.) has specific dimensions, with a diameter of 50 mm, a thickness of 3 mm, and a vent width of 2 mm. Additionally, a digital oscilloscope (Tektronix TBS1102C, Puyuan Fine Electronics Technology Co., Ltd.) can display the waveform and parameters of the electrical signal. The output voltage was modulated using a single-phase contact regulator (TDGC2-1, Zhenhua Transformer Manufacturing Co., Ltd.). During the experimental procedure, the reactor was positioned between the two electrodes of the DBD apparatus.

Experimental and analytical methods

Preparation of simulated fracturing flowback fluid

To simulate fracturing flowback fluid, a hydroxypropyl guar gum solution was utilized. An electronic balance was employed to measure 3000 mg of hydroxypropyl guar powder, which was subsequently added to a beaker containing 1 L of deionized water. Following the complete hydration of the hydroxypropyl guar powder, the resulting solution was transferred to a volumetric flask. The beaker was rinsed multiple times with deionized water, and the rinsate was also added to the volumetric flask, which was then sealed for future use.

Fracturing flowback fluid degradation experiment

(1) The Anthrone-sulfuric acid method is widely recognized as a prevalent technique in the field of carbohydrate colorimetry30. The application of a strong acid in conjunction with elevated temperatures facilitates the hydrolysis of glycosidic bonds, leading to the dehydration of monomers and the subsequent formation of furfural derivatives. These derivatives engage in a reaction with Anthrone, resulting in the production of colored compounds31. In this study, a hydroxypropyl guar gum solution was prepared and subsequently diluted to concentrations of 10 mg/L, 15 mg/L, 20 mg/L, 25 mg/L, 30 mg/L, 35 mg/L, 40 mg/L, 45 mg/L, and 50 mg/L. The absorbance of these solutions was quantified using the Anthrone-sulfuric acid method. For each concentration, absorbance measurements were conducted three times using a spectrophotometer (UV-3600 plus, Shimadzu Enterprise Management (China) Co., Ltd.) at a wavelength of 625 nm, with the average of these measurements being recorded as the final absorbance value. A scatterplot was generated to illustrate the relationship between concentration and absorbance, followed by linear regression analysis to derive the standard curve correlating the concentration and absorbance of the hydroxypropyl guar gum solution, as depicted in Fig. 2. The fitting of the standard curve and the corresponding equation is represented as Eq. (1):

where, x was the concentration of hydroxypropyl guar gum solution, mg/L; y was the absorbance of solution.

(2) The degraded solution was delivered at a rate of 0.08 mL/min using a precision injection pump (LSP02-3B, Baoding Dichuang electronic Technology Co., Ltd.). The absorbance of the solution was assessed 3 times using a spectrophotometer set to a wavelength of 625 nm, with the mean value recorded as the definitive measurement of the solution’s absorbance. The concentration of the solution was subsequently determined using Eq. (1). Ultimately, the degradation efficiency of hydroxypropyl guar gum was calculated utilizing Eq. (2).

where, D% was the degradation efficiency of hydroxypropyl guar gum, %; C0 was the concentration of hydroxypropyl guar gum solution before discharge, mg/L; Ct was the concentration of hydroxypropyl guar gum solution after discharge, mg/L.

Determination and analysis of performance of fracturing flowback fluid before and after degradation

-

(1)

Viscosity (1834, Uhler viscometer, Shanghai Liangpin Glass Instrument Factory): The viscosimeter was employed to assess the viscosity of the solution 3 times, both prior to and following the degradation process. The mean value obtained from these measurements was recorded as the final viscosity of the solution before and after degradation.

-

(2)

pH (PHS-3E, Thunder magnetic desktop LCD display acidity meter, Shanghai Yi Electrical Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd.): The pH of the solution was assessed prior to and following degradation, with each measurement conducted 3 times using a pH meter. The mean value from these measurements was recorded as the final pH result.

-

(3)

A volume of 0.2 mL of the solution, both prior to and following degradation, was introduced into the COD digester (DRB 200, Hashi Water Analysis Instrument (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.) for the digestion process. The COD of the solution was assessed using a COD detector (DR1010, Hashi Water Analysis Instrument (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.) after the digestion was completed.

Analysis of fracturing flowback fluid degradation mechanism

(1) Following the dissolution of the degraded solution in CDCl3, a liquid nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis was conducted utilizing a nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer (AVANCE III 500 M, Bruker (Beijing) Technology Co., Ltd.) to acquire data and produce the Proton Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectrum (1H NMR) and Carbon-13 Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectrum (13C NMR), respectively.

(2) Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis: The hydroxy propyl guacar solution was characterized using a Fourier infrared spectrometer (IRTracer-100, Shimadzu Enterprise Management (China) Co., Ltd.) before and after discharge. The changes of organic functional groups resulting from the degradation of hydroxypropyl guar gum solution by low-temperature plasma were compared and analyzed.

(3) Active substance capture: Prepare a diluted solution of isopropyl alcohol and 1,4-benzoquinone at a concentration ranging from 1 to 3 mM. Prior to the discharge, 1 mL of isopropyl alcohol and 1,4-benzoquinone was incorporated into the prepared solution at varying concentrations. Following the discharge, the COD of the solution was assessed.

Results and discussion

Single factor experimental analysis

Effect of DBD voltage on degradation effect

10 mL of hydroxypropyl guar gum solution was placed in the reactor. The discharge voltages were adjusted to 16 kV, 17 kV, 18 kV, 19 kV, and 20 kV at the frequency of 10 kHz, with the initial pH of the solution was 7.6. The relationship curves depicting degradation efficiency, COD, pH, and viscosity of hydroxypropyl guar gum solution with discharge time were measured and plotted, as illustrated in in Fig. 3.

As illustrated in Fig. 3a,b, the degradation efficiency of hydroxypropyl guar gum in the solution gradually increased with the extension of discharge time, while the COD gradually decreased. After 60 min, both the degradation efficiency and COD changed at a slower rate. Under the same discharge time, the degradation efficiency initially increased and then decreased as the discharge voltage was raised, whereas COD initially decreased and then increased.

When the voltage reached 18 kV, the degradation efficiency peaked at 70.92%, and COD dropped to its lowest point of 109.00 mg/L. It can be seen that high discharge voltage has negatively impacts on the degradation of fracturing flowback fluid. The reason for this is that a higher discharge voltage increases, the intensity of ultraviolet light generated by low-temperature plasma, which raises the reaction temperature. Excessive ultraviolet light and high temperature can cause some active particles in the solution to lose their reactivity, thereby inhibiting the degradation of the reflux liquid, and reducing the service life of the reactor and associated equipment32. Based on the data presented in Fig. 3c,d, under the same discharge time, the pH and viscosity of the solution exhibited a decreasing trend with increasing voltage, despite the differing. The rise in voltage initiated a significant degradation process within the solution, leading to an increase in the concentration of H+, which caused the solution to become more acidic. Consequently, as the discharge voltage increased, the pH of the solution decreased. Furthermore, the concentration of active components escalates with an extended discharge duration, which further amplifies the reactions occurring within the solution33. Meanwhile, the temperature of the reaction environment increases, leading to molecular thermal motion. The spatial structure of hydroxypropyl guar gum changes, resulting in the breakdown of a significant amount of hydroxypropyl guar gum and the generation of mannose and galactose. The intermolecular interaction forces weaken, causing a decrease in viscosity. Additionally, the viscosity of the solution viscosity may be influenced by mesoscopic structural changes. As discharge time increases, the viscosity of normal water, which is initially attributed to its mesoscopic crystalline structure, gradually decreases due to the transformation of the structure into an amorphous state. This transformation results in a higher viscosity of theb solution compared to normal water34.

In summary, when DBD plasma is employed to treat fracturing flowback fluid, significant degradation can be achieved under the following conditions: 10 kHz, a discharge voltage of 18 kV, and a discharge duration of 120 min. Under these parameters, COD removal rate and solution degradation efficiency are 78.07% and 70.92%, respectively. Moreover, the pH of the treated solution is 2.33, and its viscosity is 1.11 mPa·s. Furthermore, the fracturing flowback fluid, after undergoing low-temperature plasma treatment, complies with the second-level standard for allowable COD discharge concentration as specified in China’s petrochemical industry sewage discharge standards, which stipulates that is, COD must be less than 120 mg/L35.

Effect of initial solution pH on degradation effect

15 mL solution of hydroxypropyl guar gum was placed in a beaker, and the pH of the solution was adjusted using HCl and NaOH to achieve initial pH of 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11, respectively. 10 mL of the pH-adjusted solution was added to the reactor, where the frequency was set to 10 kHz and the discharge voltage was maintained at 18 kV. The relationship curves depicting degradation efficiency, COD, pH and viscosity of the hydroxypropyl guar gum solution over discharge time were measured and plotted, as shown in Fig. 4.

It can be observed from Fig. 4a and b that as the discharge time increases, the degradation efficiency of hydroxypropyl guar gum in the solution exhibits a gradually increasing trend, while the COD shows a gradually decreasing trend. After 60 min of discharge, both degradation efficiency and COD demonstrate a slow change. At the same discharge time, the degradation efficiency initially increases and then decreases with rising initial solution pH. Moreover, COD demonstrates a pattern of initial reduction followed by an increase. When the initial solution pH is 7, the degradation efficiency reaches its maximum at 71.41%, and COD is reduced its lowest level of 104.00 mg/L. In an acidic environment, the CO2 produced during the treatment of hydroxypropyl guar gum by low-temperature plasma easily escapes from the solution. The escaped CO2 then reacts with ·OH, which reduces the production of ·OH and effects the oxidation efficiency of ·OH in converting hydroxypropyl guar gum. Conversely, in an alkaline environment, the CO2 generated during the treatment reacts with water to form HCO3− and CO32−. The reaction rate of HCO3− and CO32− with ·OH is higher than that of ·OH with hydroxypropyl guar gum, and a decrease in its production. Therefore, both acidic and alkaline environments inhibit the degradation of hydroxypropyl guar gum solution to some extent.

In addition, the changes in pH of the solution during the reaction process under different initial solution are shown in Fig. 4c. The pH value of the solution dropped sharply within the first 30 min of discharge, and then gradually decreased. When the initial pH of the solution was 3, the pH of the hydroxypropyl guar gum solution fell to 2. These results indicat that the degradation of hydroxypropyl guar gum by DBD plasma is an acidifying process. This occurs because, during the DBD plasma discharge, oxygen and nitrogen molecules in the air are excited and converted into NOx molecules, which contribute to the reduction of the solution’s pH36. In Fig. 4d, it is observed that under different initial pH conditions, the viscosity of the solution decreased sharply after 30 min of discharge, and then continued to decline gradually. However, when the initial pH of the solution was 11, the viscosity of the solution was the lowest, and after 120 min of discharge, the viscosity was 1 mPa·s. This may be attributed to the fact that in an alkaline environment, the connections between the molecules are loosened due to electrostatic repulsion, resulting in reduced viscosity.

To sum up, the optimal process parameters for the degradation of flowback fluid using DBD plasma were as follows: discharge voltage of 18 kV, frequency of 10 kHz, discharge duration of 120 min, and an initial solution pH of 7. The COD removal rate and degradation efficiency of the flowback fluid after DBD plasma treatment were 79.07% and 71.41%, pH of 2.28, and viscosity of 1.11 mPa·s. Compared to traditional fracturing fluid degradation technology, the proposed method requires less time. In addition, it effectively degrades hydroxypropyl guar gum, reduces COD, and lowers both pH and viscosity.

The voltage-current waveform of DBD plasma operating under 18 kV is illustrated in Fig. 5. This figure indicates that the voltage waveform exhibits a relatively smooth variation, which can be attributed to the stability of the applied voltage and the filtering effect of the intervening medium layer. In contrast, the current waveform displays numerous irregular fluctuations, likely due to the dynamics of the DBD system. Specifically, the airflow and the erratic movement of the gas-liquid interface contribute to irregular changes in the capacitance of the discharge gap, leading to the observed irregularities in the electric current waveform. The dissipated power is calculated using Eq. (3)37 based on the analysis results from Fig. 5. Where, Pdis represents the dissipated power, U represents the voltage, \(\:I\) represents the current, and \(\:\varphi\:\) is the phase difference between the voltage and current. For the case shown in Fig. 5, where \(\:\varphi\:\) is 0.05π radians, the dissipated power is 355.68 W. Under this dissipated power, ensuring both high degradation efficiency and minimal energy waste.

Degradation mechanism analysis

NMR analysis

NMR analysis was conducted on the solution following the optimization of process parameters. The 1H NMR spectra and 13C NMR spectra are presented in Fig. 6a,b, respectively. The 1H NMR spectra exhibits a signal at 4.91 ppm, which falls within the typical range of 4.5–5.5 ppm for heterotopic protons associated with the sugar ring, specifically the H1 (heterotopic proton) from galactose or mannose. In the 13C NMR spectra, a signal at 76.59 ppm is observed, which is consistent with the typical range of 60–85 ppm for carbon atoms within the sugar ring, corresponding to the C2, C3, or C5 carbon signals of galactose or mannose. The integration of findings from both the 1H NMR spectra and 13C NMR spectra suggests the presence of galactose and mannose in the solution.

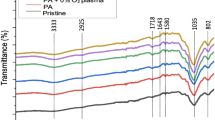

FTIR analysis

Under the process parameters of discharge voltage of 18 kV, frequency of 10 kHz and an initial solution pH of 7, the solution subjected to low-temperature plasma discharge for 0 min and 120 min was characterized using a Fourier infrared spectrometer. The results are presented in Fig. 7.

It was found in Fig. 7 that before degradation, the absorption bands corresponding to the C-O-C stretching (1069 cm− 1), the C = C stretching vibration (1552 cm− 1) and the absorption band associated with the α-glucoside bond vibration (1002 cm− 1) were present in the spectrum. This indicates that a glucoside bond existed in the solution before degradation. After 120 min of discharge degradation, the C-O-C absorption band (1069 cm− 1) disappeared, and a C-O absorption band (1120 cm− 1) resulting from contraction appeared. These observations demonstrate that the C-O-C bond in hydroxypropyl guar gum was broken and leading to its degradation into small molecules of mannose and galactose. Concurrently, a CO2 absorption band (2344 cm− 1) emerged.

Capture of free radicals

Under optimal process conditions, isopropyl alcohol and 1,4-benzoquinone were employed as trapping agents for superoxide radical anions (·O2−) and ·OH, respectively38,39. A preliminary investigation was conducted to assess the impact of these trapping agents on the COD of the hydroxypropyl guar gum solution in the DBD plasma system. The results pertaining to the changes in COD of the solution are presented in Fig. 8.

As illustrated in Fig. 8, the introduction of isopropyl alcohol markedly impeded the degradation of hydroxypropyl guar gum. Specifically, an increase in the concentration of isopropyl alcohol resulted in a rise in the COD of the DBD plasma-treated solution from 362 mg/L to 467 mg/L, while the COD removal rate diminished from 27.2% to 5.8%. These findings suggest that ·OH are crucial in the reduction of COD during the DBD plasma treatment of hydroxypropyl guar gum solutions. Conversely, as the concentration of 1,4-benzoquinone in the solution increased, the COD of the DBD plasma-treated solution exhibited minimal variation, with the COD removal rate stabilizing between 70% and 75%. This indicates that ·O2− also contribute to the degradation of hydroxypropyl guar gum in DBD plasma treatment, albeit not as the primary mechanism.

The generation process of hydroxyl radical in DBD plasma system is shown in Fig. 9. ·OH are produced through the interaction of high-energy electrons generated during the DBD plasma discharge with water molecules. At the same time, O2 is converted into oxygen atoms under the influence of a high-voltage electric field, leading to the formation of O3. When the concentration of ·OH becomes excessively, two ·OH radicals can combine to form a H2O2, which subsequently reacts with O3 to regenerate ·OH.

Combined with the results of NMR, FTIR, free radical capture and the DBD plasma discharge process, the mechanism of DBD plasma degradation in fracturing flowback fluid can be inferred as follows: ·OH and other reactive species are involved in the degradation of hydroxypropyl guar gum, significantly influencing the degradation mechanism. The interaction of these active substances with hydroxypropyl guar gum results in the cleavage of the C-O-C bond, leading to the formation of mannose and galactose, as shown in Fig. 10.

Conclusion

(1) DBD plasma can effectively degrade fracturing flowback fluid. During the degradation of fracturing flowback fluid by DBD plasma, the glycosidic bonds of hydroxypropyl guar gum are cleaved, generating mannose and galactose.

(2) The optimal process parameters for DBD plasma degradation of fracturing flowback fluid were as follows: discharge voltage of 18 kV, frequency of 10 kHz, discharge duration of 120 min, and an initial solution pH 7. Following DBD plasma treatment, COD removal rate and solution degradation efficiency of fracturing flowback fluid were 79.07% and 71.41%, respectively. The pH decreased to 2.28, and viscosity was measured at 1.11 mPa·s. The degradation indices complied with the second-level standard for allowable COD emission concentration as specified in China’s sewage discharge standards for the petrochemical industry.

(3) The degradation rate and chemical oxygen demand (COD) reduction achieved through dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasma treatment of fracturing flowback fluid surpass those of physical and biological methods, while demonstrating comparability to chemical methods. In contrast to chemical approaches, DBD plasma treatment offers several advantages, including ease of operation, reduced treatment duration, and lower reagent consumption. DBD plasma treatment of fracturing flowback fluid not only addresses the limitations of traditional fracturing flowback fluid treatment methods but also provides important support for the sustainable development of the oil industry.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wang, H., Lu, L., Chen, X., Bian, Y. & Ren, Z. J. Geochemical and microbial characterizations of flowback and produced water in three shale oil and gas plays in the central and Western united States. Water Res. 164, 114942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2019.114942 (2019).

Ma, G. et al. An integrated decision support tool for treatment and beneficial use of non-traditional water supplies – Part II. Marcellus and barnett shale case studies. J. Water Process. Eng. 25, 258–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2018.08.007 (2018).

Wang, D. et al. The roles of suspended solids in persulfate/Fe2+ treatment of hydraulic fracturing wastewater: synergistic interplay of inherent wastewater components. Chem. Eng. J. 388, 124243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2020.124243 (2020).

Wang, X. et al. Effect of anthraquinone-2,6-disulfonate on anaerobic digestion of fracturing flowback fluid under high salinity stress. J. Water Process. Eng. 50, 103260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2022.103260 (2022).

Zeng, F. et al. Enhanced remediation of fracturing flowback fluids by the combined application of a bioflocculant/biosurfactant-producing Bacillus Sp. SS15 and its metabolites. Chemosphere 302, 134870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.134870 (2022).

Han, H. et al. Green Ferrate(VI) for multiple treatments of fracturing wastewater: demulsification, visbreaking, and chemical oxygen demand removal. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 1857. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20081857 (2019).

Wang, F. et al. Mechanism analysis of hydroxypropyl Guar gum degradation in fracture flowback fluid by homogeneous sono-Fenton process. Ultrason. Sonochem. 93, 106298–106298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106298 (2023).

Ren, H. Y. et al. Treatment for hydraulic fracturing flowback fluid of shale gas by ceramic membrane-ED-H/L pressure RO process. J. Water Process. Eng. 52, 103551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2023.103551 (2023).

Dansawad, P. et al. Smart membranes for oil/water emulsions separation: A review. Adv. Membr. 2, 100039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advmem.2022.100039 (2022).

Nueraji, M. et al. Mechanically-robust electrospun nanocomposite fiber membranes for oil and water separation. Environ. Res. 220, 115212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2023.115212 (2023).

Yan, B. et al. Performance and microbial community analysis of combined bioreactors in treating high–salinity hydraulic fracturing flowback and produced water. Bioresour Technol. 386, 129469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2023.129469 (2023).

Riley, S. M., Oliveira, J. M. S., Regnery, J. & Cath, T. Y. Hybrid membrane bio-systems for sustainable treatment of oil and gas produced water and fracturing flowback water. Sep. Purif. Technol. 171, 297–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2016.07.008 (2016).

Freedman, D. E. et al. Biologically active filtration for fracturing flowback and produced water treatment. J. Water Process. Eng. 18, 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2017.05.008 (2017).

Huo, J. et al. Effects of chemically reactive species generated in plasma treatment on the physico-chemical properties and biological activities of polysaccharides: an overview. Carbohyd Polym. 342, 122361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2024.122361 (2024).

Baig, S. & Sajjadi, B. Non-thermal plasma enhanced catalytic conversion of methane into value added chemicals and fuels. J. Energy Chem. 97, 265–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jechem.2024.05.024 (2024).

Wang, R. et al. Low-temperature plasma-assisted synthesis of iron and nitrogen co-doped CoFeP-N nanowires for high-efficiency electrocatalytic water splitting. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 352, 124027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2024.124027 (2024).

Hou, D. et al. Efficient regeneration of waste LiFePO4 cathode material by short process low temperature plasma assisted nitrogen doped technology. J. Power Sources. 613, 234845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2024.234845 (2024).

Shen, W., Wu, H., Tan, Z., Lin, S. & Guan, C. Synergistic low-temperature plasma degradation of Tetracycline with ferrocene. J. Environ. Manage. 371, 123220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.123220 (2024).

Acheampong, A., Bondzie-Quaye, P., Fetisoa, M. R. & Huang, Q. Applications of low-temperature plasma technology in microalgae cultivation and mutant breeding: A comprehensive review. Bioresource Technol. 419, 132019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2024.132019 (2025).

Chang, R. et al. Efficient carbon dioxide conversion by nickel ferrite-based catalysts derived from metallurgical electroplating sludge collaborating with low-temperature plasma. J. Colloid Interf Sci. 682, 353–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2024.11.201 (2025).

Shen, X., Gao, X., Zhang, S. & Wang, C. Experimental study of low temperature plasma synergistic catalyst for treatment of DEP in water. Chem. Eng. Process. - Process. Intensif. 203, 109892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cep.2024.109892 (2024).

Ruan, J. et al. Tailored design of 2D MOF derived carbon boosting the low temperature plasma catalysis for water treatment: the role of graphitization and hierarchical porous structure. Chem. Eng. J. 470, 144316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2023.144316 (2023).

Wang, J., Zhang, J., Shangguan, Y., Yang, G. & Liu, X. Degradation performance and mechanism of microcystins in aquaculture water using low-temperature plasma technology. Environ. Pollut. 347, 123744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2024.123744 (2024).

Karoui, S. et al. Intensification of non-thermal plasma for aqueous Ciprofloxacin degradation: optimization study, mechanisms, and combined plasma with photocatalysis. J. Water Process. Eng. 50, 103207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2022.103207 (2022).

Zhang, A. et al. Motivation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species by a novel non-thermal plasma coupled with calcium peroxide system for synergistic removal of sulfamethoxazole in waste activated sludge. Water Res. 212, 18128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2022.118128 (2022).

Huang, L., Chen, X., Wan, B. & Xu, S. Synergy of dielectric barrier discharge plasma and magnetically separable MOF-derived Co@C composite for the improved degradation of Norfloxacin antibiotic in water. Sep. Purif. Technol. 306, 122488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2022.122488 (2023).

Han, S., Mao, D., Wang, H. & Guo, H. An insightful analysis of dimethyl phthalate degradation by the collaborative process of DBD plasma and Graphene-WO3 nanocomposites. Chemosphere 291, 132774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.132774 (2022).

Lu, W. et al. Improvement of degradation of orange G in aqueous solution by Fe2+ added in dielectric barrier discharge plasma system. J. Water Process. Eng. 47, 102707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2022.102707 (2022).

Wang, X., Wang, L., Liu, K., Zhu, C. & Guan, F. Study on degradation of wastewater containing PAM catalyzed by nonequilibrium plasma and γ-Al2O3. J. Water Process. Eng. 49, 103065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2022.103065 (2022).

Roe, J. H. The determination of sugar in blood and spinal fluid with anthrone reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 212, 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9258(18)71120-4 (1955).

Laurentin, A. & Edwards C.A. A microtiter modification of the anthrone-sulfuric acid colorimetric assay for glucose-based carbohydrates. Anal. Biochem. 315 (02), 143–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-2697(02)00704-2 (2003).

Jiang, X., Guan, F., Wang, X., Li, D. & Shi, M. Study on synergistic catalytic degradation of wastewater containing polyacrylamide catalyzed by low–temperature plasma-H2O2. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 30, 112206–112221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-30287-0 (2023).

Wong, K. S., Chew, N. S., Low, M. & Tan, M. K. Plasma-activated water: Physicochemical properties, generation techniques, and applications. Processes. 11, 2213; (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/pr11072213

Shaji, M., Rabinovich, A., Surace, M., Sales, C. & Fridman, A. Physical properties of plasma-activated water. Plasma 6, 45–57. https://doi.org/10.3390/plasma6010005 (2023).

Standardization Administration of. The People’s Republic of China. GB 8978–1996 (Integrated wastewater discharge standard, 1996).

Wu, L. et al. Degradation of methylene blue via dielectric barrier discharge plasma treatment. Water 11 (1818). https://doi.org/10.3390/w11091818 (2019).

Pampoukis, G., Zwietering, M. H. & ,den Besten H.M.W. Ranking factors affecting the decontamination efficacy of non-thermal plasma: the approach of dissipated power per plasma volume through machine learning modeling. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 96, 103773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifset.2024.103773 (2024).

Monteagudo, J. M., San Martin, D. A. & Carnicer, I. Roles of different intermediate active species in the mineralization reactions of phenolic pollutants under a UV-A/C photo-Fenton process. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 106, 242–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2011.05.034 (2011).

Hwang, S., Huling, S. & KO, S. Fenton-like degradation of MTBE: effect if iron counter anion and radical scavenger. Chemosphere 78, 563–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.11.005 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by Heilongjiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China LH2022E026.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Meiqi Shi: conduct experiments, data analysis and manuscript writing. Fuping Feng, Jianwei Zhang: conceive experiments, data curation, project administration. Hong Jiang: conduct experiments, data collection. Xueqin Wang: data analysis, manuscript editing. All the authors approved and contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, M., Feng, F., Zhang, J. et al. Feasibility study of fracturing flowback fluid degradation by dielectric barrier discharge plasma. Sci Rep 15, 17954 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01251-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01251-4