Abstract

Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) based on creatinine (eGFRCreatinine) or cystatin C (eGFRCystatinC) require steady-state conditions and thus have limitations in intensive care unit (ICU) patients. Gentamicin is a potential exogenous marker for eGFR but poorly investigated. This retrospective study included adult ICU patients (≥ 18 years) treated with gentamicin and not on renal replacement therapy (RRT) at admission. eGFRCreatinine and eGFRCystatinC were calculated using the LM-rev and CAPA equations, respectively. Gentamicin clearance was estimated using a population pharmacokinetic model and used as eGFRGentamicin. Agreement between eGFRs vs. eGFRGentamicin and prediction of RRT and mortality for each eGFR were assessed. 254 patients were included of whom 11% (n = 28) received RRT later and 19% (n = 49) were dead at 30 days. The bias was 12 mL/min/1.73 m2 and 8 mL/min/1.73 m2, respectively, and the limits of agreement − 31–55 mL/min/1.73m2 and − 46–62 mL/min/1.73m2 for the agreement between eGFRGentamicin vs. eGFRCreatinine, and for eGFRGentamicin vs. eGFRCystatinC, respectively. The c-indexes for predicting RRT during ICU stay were 0.75 (0.64–0.86), 0.77 (0.66–0.88) and 0.80 (0.69–0.90) for eGFRCreatinine, eGFRCystatinC and eGFRGentamicin respectively, and for 30-day mortality 0.61 (0.52–0.70), 0.61 (0.52–0.70) and 0.63 (0.54–0.72) respectively. In ICU patients already receiving gentamicin, eGFRGentamicin derived from population PK models can be used to assess renal function and could potentially help improve dosing of other renally cleared drugs like the β-lactams during early phase of infections in the ICU.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A reliable assessment of the renal function in intensive care unit (ICU) patients with infections such as sepsis/septic shock, is important for several aspects of patient management. Without correct renal function measures, dosing to achieve adequate target organ levels of drugs with primarily renal elimination, such as many antimicrobial agents, is challenging. In critically ill patients, renal function varies both between and within patients since they are at risk of both augmented renal clearance (ARC) and acute kidney injury (AKI). ARC, a state of hyperfunctioning kidneys, presents a high risk of therapeutic failures for drugs with renal elimination such as the β-lactam antibiotics in the initial and most acute phase of infections in the ICU1,2,3,4. Pooled prevalence of ARC in the critically ill population has been reported to be 39% in one meta-analysis4. On the other hand, decreased renal function due to AKI can be seen in 60% of the patients with sepsis, and is associated with increased mortality risk and morbidity5,6,7, as well as risk for overdosing and toxicity of renally eliminated drugs.

The glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is regarded as the best indicator of global kidney function. GFR cannot be measured directly, instead, GFR can be assessed based on measured clearance (CL) of exogenous filtration markers as inulin, EDTA or iohexol, which are considered to be the reference methods8. However, these methods are time-consuming, expensive and impractical in unstable ICU patients. Instead, estimated GFR (eGFR) from serum levels of endogenous filtration markers such as creatinine (eGFRCreatinine) and cystatin C (eGFRCystatinC) are most commonly used in the ICU. Yet, these markers of renal function have limitations, particularly in critically ill patients without steady-state conditions and can both under and overestimate GFR9,10,11. The search for a better exogenous marker has been ongoing for years and clearance of aminoglycosides has been proposed as a possible option in critically ill patients already receiving this drug in the ICU because of their stable characteristics described below9.

Gentamicin is an aminoglycoside antibiotic that has been in use for parenteral administration since 197112. Currently it is mostly used in combination therapy in cases of septic shock and Gram-negative infections to spare carbapenems. As gentamicin is freely filtered in the glomerulus, has little non-renal CL and is neither secreted nor reabsorbed in the kidney, it has potential as an exogenous marker of eGFR in patients already receiving this treatment9. Earlier studies evaluating if the elimination capacity of gentamicin is predictive of GFR have shown conflicting results13,14,15. The performance of estimated gentamicin clearance (eGFRGentamicin) in predicting hard endpoints, associated with renal function, such as subsequent renal replacement therapy (RRT) during ICU stay and mortality has not been investigated previously.

Consequently, the aim of the study was to investigate how eGFRGentamicin derived from gentamicin serum concentrations by a population pharmacokinetic model corresponds to estimated eGFR using cystatin C (eGFRCystatinC) or creatinine (eGFRCreatinine) equations in an ICU setting. Moreover, to link these methods to renal function, we investigated the association between the three methods of eGFR and RRT initiated during ICU stay. Finally, we investigated the association between the three methods of eGFR and short (30-day) and long-term mortality since biomarkers of renal function are strong predictors of these16.

Material and method

Study design, patients and clinical data

This study was a retrospective observational study conducted between January 1st, 2009 and December 31st, 2013 in the general ICU of Uppsala University Hospital. Adult patients (≥ 18 years) given at least one gentamicin dose during their ICU stay with a corresponding sample of gentamicin concentration taken according to local guidelines were included. Exclusion criteria were age < 18 years or RRT before ICU stay. Demographic data as well as daily fluid balance, time on RRT during ICU stay, dose and administration time for gentamicin as well as time for gentamicin serum concentration sampling, were collected from the medical records. The corresponding results of plasma creatinine, cystatin C, and gentamicin concentrations following the first dose for each patient were collected from the laboratory information system of the Department of Clinical Chemistry and Pharmacology at Uppsala University Hospital. A follow-up was performed on July 8th, 2020, and the date of death (used for 30-day mortality) and overall mortality was collected from the patients’ medical records.

Results

Patients

In total 254 patients with a median age of 65.6 (IQR 54.3–74.2) years were included in the analysis and given one gentamicin dose (range 1–5). The 30-day mortality was 19% (n = 49) and 11% (n = 28) received RRT during the ICU stay. The patients’ clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1.

The individual CL was estimated with a median relative standard error of 21% (IQR 19–28%). eGFR values were similar in those with available height and weight data and those with missing data as well as in female and male patients (See Supplementary Table S1 and S2 online).

The correlations between eGFRGentamicin and eGFRCreatinine respectively eGFRCystatinC are presented in Fig. 1. The correlation coefficients and coefficients of determination were similar for both analyses and indicated a positive linear relationship.

The agreement between eGFRGentamicin and eGFRCreatinine respectively eGFRCystatinC is presented as two Bland-Altman plots in Fig. 2.

Bland-Altman plot of the agreement between A) eGFRGentamicin and eGFRCreatinine B) eGFRGentamicin and eGFRCystatinC. The blue line marks the bias. Red lines mark the LoA. Dashed red respectively blue lines mark the 95% CI of the bias and the LoA. eGFR; estimated glomerular filtration rate, LoA; limits of agreement.

For the agreement between eGFRGentamicin and eGFRCreatinine, the bias was 12 mL/min/1.73 m2 and the limits of agreement (LoA) 55 − 31 mL/min/1.73 m2. The corresponding results for the agreement between eGFRGentamicin and eGFRCystatinC were 8 mL/min/1.73 m2 (bias) and 62 − 46 (LoA) mL/min/1.73 m2. The correlations between bias for eGFRCreatinine vs. eGFRGentamicin and eGFRCystatinC vs. eGFRGentamicin and weight were r=-0.37, r2 = 0.13 and r=-0.34, r2 = 0.11, respectively and the corresponding correlations for age were r=-0.05, r2 = 0.00 and r=-0.15, r2 = 0.02.

In Fig. 3, the performance of the three different eGFR methods to predict RRT during the ICU stay are presented as ROC curves.

The ROC-AUC or the c-index was 0.75 (0.64–0.86) for eGFRCreatinine, 0.77 (0.66–0.88) for eGFRCystatinC and 0.80 (0.69–0.90) for eGFRGentamicin. The corresponding odds ratios (OR) were 0.96 (0.94–0.98), 0.96 (0.93–0.98) and 0.94 (0.92–0.97).

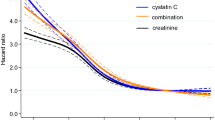

The risk of death within 30 days after first given gentamicin dose in the ICU predicted by eGFRCreatinine, eGFRCystatinC or eGFRGentamicin are presented as ROC curves in Fig. 4.

The c-indexes were 0.61 (0.52–0.70), 0.61 (0.52–0.70) and 0.63 (0.54–0.72) respectively. The OR were 0.99 (0.98-1.00), 0.99 (0.98-1.00) respectively 0.98 (0.97-1.00). The risk of death over time during the follow-up period calculated as hazard ratios (HR) were 0.99 (0.99-1.00) for eGFRCreatinine, 0.99 (0.99-1.00) for eGFRCystatinC and 0.99 (0.98–0.99) for eGFRGentamicin.

Discussion

In a Swedish ICU cohort of 254 patients, treated with at least one gentamicin dose during their ICU stay, we found low agreement despite low bias between eGFRGentamicin and eGFRCreatinine respectively eGFRCystatinC. However, when we assessed the three eGFR methods as predictors for risk of RRT during the ICU stay and 30 day-mortality the three eGFR methods performed similarly with a trend towards higher c-index for eGFRGentamicin.

The finding that gentamicin CL shows a low agreement compared to the other two endogenous eGFR methods is not surprising since it is well-known that neither eGFRCreatinine nor eGFRCystatinC is accurate in critically ill ICU patients9,10,11. One reason behind this is the pathophysiological changes in critically ill patients causing alterations in renal hemodynamics9. Modern interventions during ICU care can also affect both creatinine and cystatin C levels causing false estimation of GFR9,17,18.

Creatinine is produced in all muscle cells and its serum levels are influenced by gender, ethnicity, muscle mass, physical activity and diet among others19,20. Nutritional status and muscle wasting due to ICU care will affect the production of creatinine. The equations for eGFR are based on patient cohorts with low severity of illness without muscle wasting or nutrition deficit, contrary to ICU patients. We saw a small but consistent association in the bias, i.e. lack of agreement, between eGFRCreatinine and eGFRGentamicin suggesting that muscle mass contributes to this. There are also other factors influencing creatinine in the critically ill that make this marker of kidney function less reliable in ICU situations, like AKI and dialysis17,18. Creatinine is also secreted in the renal tubules, which is another limitation since it may lead to false overestimation of CL compared to mGFR and making this biomarker an unreliable predictor of renal drug elimination and dosing of β-lactam antibiotics in the ICU21,22.

Cystatin C is generated in all nucleated cells and is less affected by muscle mass than creatinine but has been shown to be affected by levels of thyroid hormones, corticosteroids and possibly by obesity, smoking and inflammation10,17,18,23,24,25,26. Despite many improvements compared to eGFRCreatinine, a systematic review showed that in critically ill, eGFRCystatinC both underestimates and overestimates renal function compared to measured GFR (mGFR) in five studies on ICU patients10.

Gentamicin on the other hand was in some small cohort studies in the 1980s and 1990s suggested to be a potential exogenous marker for GFR in patients with infections that already receive treatment with this compound in the ICU. Koren et al. reported that GFR in 38 preterm infants in the ICU could be estimated by using gentamicin pharmacokinetics calculations based on serum concentrations of gentamicin with good results compared to measured creatinine CL27. Zarowitz et al. found that aminoglycoside CL in ten tobramycin or gentamicin-treated ICU patients was as good as measured inulin CL and 24-hour urinary creatinine CL to estimate GFR in critically ill patients15. Hickling et al. on the other hand found that aminoglycoside (AG) CL is predicted as poorly by renal AG CL as by creatinine CL in critically ill patients and proposed that their findings suggested a non-renal aminoglycoside CL14. Jones et al. reported that AG CL was a good estimate of creatinine CL in 100 tobramycin or gentamicin-treated ICU patients compared to seven other used estimates13. For some reason, possibly due to the development of equations using cystatin C, these reports regarding gentamicin as an exogenous marker of GFR fell into oblivion. Compared to these early studies our study also focuses on comparing eGFRGentamicin to eGFRCystatinC besides eGFRCreatinine and we also estimate eGFRGentamicin using a population PK model-based method and renal endpoints for the first time.

Decreased eGFR is associated with poor survival and acute RRT during ICU stay28,29. Previous studies of eGFR have also reported that cystatin C alone or together with creatinine-based equations can be used to predict the risk for long-term cardiovascular death30,31,32. Our finding with similar c-index for eGFRGentamicin respectively eGFRCystatinC in predicting the risk of 30-day mortality and risk for RRT during ICU stay strengthens the hypothesis that gentamicin CL could be as good as the other two eGFR biomarkers to estimate kidney function in the ICU. The three eGFR methods were also comparable when it comes to predicting the overall risk of death during the follow-up period which further strengthens this conclusion.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that tries to compare eGFRGentamicin, estimated from serum gentamicin concentrations using a PK model-based approach, in a large ICU cohort of 254 patients to the modern equations for eGFRCreatinine and eGFRCystatinC, the standard estimates of GFR in the ICU in many countries. We also assess the eGFRGentamicin method as a predictor of both mortality and RRT during ICU care for the first time i.e. not only comparing it to other eGFR methods but to clinical outcomes related to renal function. However, the study has some limitations. Firstly, we did not compare the eGFRGentamicin with the reference standard of mGFR, inulin. Secondly, gentamicin is a drug with nephrotoxic potential and although unlikely, it cannot be ruled out that the correlation between eGFRGentamicin and the need for RRT during ICU stay could be partly explained by this fact. Another limitation is that the use of gentamicin has declined during the last decade and the usefulness of developing a new exogenous GFR method based on gentamicin can be questioned. However, in certain patient groups, like in the neonatal ICU, patients in septic shock, and in countries where gentamicin is used together with β-lactams as empirical treatment in infections with unknown cause because of antimicrobial stewardship reasons, the use of eGFRGentamicin could be a good alternative. In clinical practice, this means that eGFRGentamicin in the mentioned groups of patients could be used e.g. to guide dose adjustments of other renally cleared drugs like the β-lactam during the first critical days of treatment.

Analysis of gentamicin concentrations is also well-established in almost all hospitals which makes the method widely available with short test turnaround times. When it comes to the patient cohort no clinical data on the type of infection or underlying conditions were collected but on the other hand, an ICU cohort of 254 patients is relatively large and the finding of our study is applicable to a general ICU population.

In recent years, the development of several user-friendly software for estimating PK parameters such as CL33, as well as predicting individual dosing regimens, opens new possibilities for the clinical use of gentamicin concentrations derived from ICU patients to be used for estimating their individual GFR from estimated gentamicin CL. This could be beneficial for the critically ill population when it comes to both improved dosing of other renally cleared drugs like the β-lactams, but might also be a helpful tool for the intensive care doctors to use to predict the risk of mortality and need for early RRT.

Our findings support exploring the use of gentamicin as an exogenous marker of renal function further. Preferably, by comparing the eGFRGentamicin, derived using a population PK model approach, to mGFR by iohexol, or possibly inulin, the reference standard, in an ICU population, with severe infections as a first step. A possible future application could be to integrate a renal function estimate based on gentamicin CL in an easy-to-use model-informed precision dosing software used for β-lactams to guide dosing in ICU patients during the first critical days of treatment34.

Conclusion

In Swedish ICU patients treated with gentamicin, the use of estimated gentamicin CL from measured gentamicin serum concentrations was found to be a potential exogenous marker of renal function that needs to be explored further. eGFRGentamicin was also found to be as good as eGFRCreatinine and eGFRCystatinC in predicting mortality and the need for early RRT in the ICU.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the regional ethics review board in Uppsala (Registration number 2016/157) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent revisions. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the regional ethics review board in Uppsala waived the need of obtaining informed consent. The STROBE statement was followed for reporting.

Measurement of creatinine, Cystatin C and gentamicin

Measurement of plasma creatinine, cystatin C and serum concentrations of gentamicin were performed at the accredited Department of Clinical Chemistry and Pharmacology at Uppsala University Hospital. Both creatinine and cystatin C were analysed on Architect ci8200 (Abbot Laboratories, Abbot Park, Ill, USA). Plasma creatinine was analysed with an enzymatic method calibrated by the manufacturer using the isotope dilution mass spectrometric method (IDMS). Plasma cystatin C was analysed with an assay from Gentian (Gentian, Moss, Norway) calibrated against the international calibrator ERM-DA471/IFCC.

Serum gentamicin concentrations were analysed with two different methods during the study period. Between 2009 and 2011 the analysis was made using fluorescence polarization immune assay (F-PIA) on TDx Flex from Abbott, and from September 2011 with chemiluminescence microparticle immunoassay (CMIA) method on Architect, Abbot. The two methods produced comparable results according to the validation performed by the accredited laboratory.

Estimation of GFR

Gentamicin CL was estimated for each individual using Bayesian estimation34, applying the first measured concentration (one sample, 95% of samples collected 6–12 h after dose) and a population pharmacokinetic model described by Hodiamont et al.35. This is a two-compartmental model based on prospective data from 59 critically ill patients treated with a mean gentamicin dose of 5.1 mg/kg (± 1.1, SD). The data consisted of 416 gentamicin concentrations from TDM sampling (peak and random time point 6–23 h after administration) and measurements from waste material. The model includes inter-individual variability for CL (75%) and central volume of distribution (27%) but no covariates35. The model was selected following an evaluation of goodness-of-fit plots and a simulation-based prediction corrected visual predictive check36. Estimated CL (mL/min) was converted to relative value (mL/min/1.73m2) by applying an equation for body surface area37, and used as eGFRGentamicin. eGFRCreatinine and eGFRCystatinC (mL/min/1.73m2) were calculated from the LM-rev and the CAPA-equations, respectively38,39.

Statistics

To detect a 10 ml/min bias with a mean eGFR of 60 ml/min and a standard deviation of 30 ml/min, with an alpha of 0.05 and a power of 0.9, 191 patients needed to be included in the study.

Missing data for height (47 patients) and weight (20 patients) were imputed with the median from all patients in the study. No other variables had missing data.

Data are presented as median (IQR) or as number of observations (%) unless otherwise stated. Pearson’s correlation coefficients and coefficients of determination were used to assess correlations. The agreement and bias between eGFRGentamicin and eGFRCreatinine, respectively eGFRCystatinC were calculated and presented in Bland-Altman plots. Univariate logistic regression, presented as receiver operating characteristic curves (ROC-curves), was used to assess the association between the three eGFR methods and the risk of RRT during ICU stay as well as 30-day mortality. The association between the three eGFR methods and overall mortality during the follow-up period was analysed using Cox proportional hazard regression.

Software

Statistica software, version 14.1 (Statsoft, Tulsa, OK, USA) was used for the statistics. Gentamicin CL was estimated using Bayesian estimation in the software NONMEM (version 7.4, Icon Development Solutions, Hanover, MD, USA)40, assisted by Pearl-Speaks-NONMEM41. R version 3.5 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) was used for data management, with the xpose4 package41, for population PK model evaluation.

Data availability

Anonymised datasets generated during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AKI:

-

Acute kidney injury

- ARC:

-

Augmented renal clearance

- BSA:

-

Body surface area

- CL:

-

Clearance

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- eGFRCreatinine :

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate based on creatinine (LM-rev equation)

- eGFRCystatinC :

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate based on cystatin C (CAPA-equation)

- eGFRGentamicin :

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate based on gentamicin clearance

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- mGFR:

-

Measured glomerular filtration rate

- RRT:

-

Renal replacement therapy

References

Huttner, A. et al. Augmented renal clearance, low β-lactam concentrations and clinical outcomes in the critically ill: an observational prospective cohort study. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 45 (4), 385–392 (2015).

Carrie, C. et al. Association between augmented renal clearance and clinical failure of antibiotic treatment in brain-injured patients with ventilator-acquired pneumonia: A preliminary study. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain Med. 37 (1), 35–41 (2018).

Mahmoud, S. H. & Shen, C. Augmented renal clearance in critical illness: an important consideration in drug dosing. Pharmaceutics, 9(3). (2017).

Hefny, F. et al. Drug dosing in critically ill adult patients with augmented renal clearance. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 47 (5), 607–620 (2022).

Bagshaw, S. M. et al. Acute kidney injury in septic shock: clinical outcomes and impact of duration of hypotension prior to initiation of antimicrobial therapy. Intensive Care Med. 35 (5), 871–881 (2009).

Bouchard, J. et al. A prospective international multicenter study of AKI in the intensive care unit. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 10 (8), 1324–1331 (2015).

Zarbock, A. et al. Sepsis-associated acute kidney injury-treatment standard. Nephrol. Dial Transpl. 39 (1), 26–35 (2023).

Soveri, I. et al. Measuring GFR: a systematic review. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 64 (3), 411–424 (2014).

Sunder, S. et al. Estimation of renal function in the intensive care unit: the Covert concepts brought to light. J. Intensive Care. 2 (1), 31 (2014).

Adingwupu, O. M. et al. Cystatin C as a GFR Estimation marker in acute and chronic illness: A systematic review. Kidney Med. 5 (12), 100727 (2023).

Roy, R. et al. The Estimation of glomerular filtration in acute and critical illness: challenges and opportunities. Clin. Biochem. 118, 110608 (2023).

Chen, C. et al. Update on new medicinal applications of gentamicin: evidence-based review. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 113 (2), 72–82 (2014).

Jones, T. E., Peter, J. V. & Field, J. Aminoglycoside clearance is a good estimate of creatinine clearance in intensive care unit patients. Anaesth. Intensive Care. 37 (6), 944–952 (2009).

Hickling, K. G. et al. Serum aminoglycoside clearance is predicted as poorly by renal aminoglycoside clearance as by creatinine clearance in critically ill patients. Crit. Care Med. 19 (8), 1041–1047 (1991).

Zarowitz, B. J., Robert, S. & Peterson, E. L. Prediction of glomerular filtration rate using aminoglycoside clearance in critically ill medical patients. Ann. Pharmacother. 26 (10), 1205–1210 (1992).

Helmersson-Karlqvist, J. et al. Cystatin C predicts long term mortality better than creatinine in a nationwide study of intensive care patients. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 5882 (2021).

Inker, L. A. & Titan, S. Measurement and Estimation of GFR for use in clinical practice: core curriculum 2021. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 78 (5), 736–749 (2021).

Levey, A. S. et al. Measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate: current status and future directions. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 16 (1), 51–64 (2020).

Perrone, R. D., Madias, N. E. & Levey, A. S. Serum creatinine as an index of renal function: new insights into old concepts. Clin. Chem. 38 (10), 1933–1953 (1992).

Levey, A. S., Perrone, R. D. & Madias, N. E. Serum creatinine and renal function. Annu. Rev. Med. 39, 465–490 (1988).

Ma, Y. et al. Characterization of the renal tubular transport of creatinine by activity-based protein profiling and transport kinetics. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 180, 106342 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. Tubular secretion of creatinine and kidney function: an observational study. BMC Nephrol. 21 (1), 108 (2020).

McMahon, G. M. & Waikar, S. S. Biomarkers in nephrology: core curriculum 2013. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 62 (1), 165–178 (2013).

Foster, M. C. et al. Non-GFR determinants of Low-Molecular-Weight serum protein filtration markers in the elderly: AGES-Kidney and MESA-Kidney. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 70 (3), 406–414 (2017).

Stevens, L. A. et al. Factors other than glomerular filtration rate affect serum Cystatin C levels. Kidney Int. 75 (6), 652–660 (2009).

Filler, G. et al. Cystatin C as a marker of GFR–history, indications, and future research. Clin. Biochem. 38 (1), 1–8 (2005).

Koren, G., James, A. & Perlman, M. A simple method for the Estimation of glomerular filtration rate by gentamicin pharmacokinetics during routine drug monitoring in the newborn. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 38 (6), 680–685 (1985).

Peralta, C. A. et al. Detection of chronic kidney disease with creatinine, Cystatin C, and urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio and association with progression to end-stage renal disease and mortality. Jama 305 (15), 1545–1552 (2011).

Sitbon, A. et al. Accuracy of clinicians’ ability to predict the need for renal replacement therapy: a prospective multicenter study. Ann. Intensive Care. 12 (1), 95 (2022).

Helmersson-Karlqvist, J. et al. Addition of Cystatin C predicts cardiovascular death better than creatinine in intensive care. Heart 108 (4), 279–284 (2022).

Shlipak, M. G. et al. Cystatin C versus creatinine in determining risk based on kidney function. N Engl. J. Med. 369 (10), 932–943 (2013).

Ni, L. et al. Cystatin C, associated with hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke, is a strong predictor of the risk of cardiovascular events and death in Chinese. Stroke 38 (12), 3287–3288 (2007).

Kantasiripitak, W. et al. Software tools for Model-Informed precision dosing: how well do they satisfy the needs?? Front. Pharmacol. 11, 620 (2020).

Wicha, S. G. et al. From therapeutic drug monitoring to Model-Informed precision dosing for antibiotics. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 109 (4), 928–941 (2021).

Hodiamont, C. J. et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring of gentamicin peak concentrations in critically ill patients. Ther. Drug Monit. 39 (5), 522–530 (2017).

Bergstrand, M. et al. Prediction-corrected visual predictive checks for diagnosing nonlinear mixed-effects models. Aaps J. 13 (2), 143–151 (2011).

Du Bois, D. & Du Bois, E. F. A formula to estimate the approximate surface area if height and weight be known. 1916. Nutrition, 5(5): p. (1989). 303 – 11; discussion 312-3.

Björk, J. et al. Revised equations for estimating glomerular filtration rate based on the Lund-Malmö study cohort. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 71 (3), 232–239 (2011).

Grubb, A. et al. Generation of a new Cystatin C-based estimating equation for glomerular filtration rate by use of 7 assays standardized to the international calibrator. Clin. Chem. 60 (7), 974–986 (2014).

Beal, S. L., Boeckmann, S. L. & Bauer, R. J. (eds) AJ, and, NONMEM 7.4 Users Guides. ICON plc. Gaithersburg, MD. (2017).

Keizer, R. J., Karlsson, M. O. & Hooker, A. Modeling and simulation workbench for NONMEM: tutorial on Pirana, PsN, and xpose. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst. Pharmacol. 2 (6), e50 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Fredrik Elving (FE), former medical student at Uppsala University, for help collecting data from the patients’ medical records as part of his scientific project.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Uppsala University.

The study was supported by unrestricted grants from Regional Research Council Mid Sweden (RFR-560491); Sweden’s innovation agency VInnova (within the project PLATINEA, grant number 2018–03340, 2021–02699) and the Uppsala University Hospital research fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ML, AKS, MF, AL designed the study. ML, AL and FE collected patient data. AKS prepared the dataset. EN, MS designed and performed the population PK analysis of gentamicin clearance. ML, AKS wrote the first draft. All authors revised the paper and approved the final version for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Smekal, AK., Swartling, M., Nielsen, E.I. et al. Utilizing gentamicin concentrations to estimate glomerular filtration rate in intensive care unit patients. Sci Rep 15, 17262 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01256-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01256-z