Abstract

This study successfully synthesized Hydrochar (HC) and Modified Hydrochar (MHC), two affordable and environmentally friendly adsorbents, utilizing an integration of chemical activation and hydrothermal carbonization. Subsequently, the artificially produced adsorbents were employed to eradicate the Alizarin Red S (ARS) dye from the aquatic environment. The physical and chemical nature of the HC and MHC adsorbents were assessed by various characterization approaches namely, FT-IR, SEM, XRD, and BET analysis. MHC and HC adsorbents have surface areas of 23.435 m2/g and 14.519 m2/g, according to BET analysis. The pore diameters of the MHC and HC adsorbents have been 3.05489 nm and 3.06075 nm, respectively. These materials’ pore diameters, ranging from 2 to 50 nm, show that the created materials are mesopores. For both adsorbents, the most fitting model based on the two and three-parameter models is the Freundlich isotherm. According to the adsorption kinetics, the system obeys physisorption for both adsorbents. Both adsorbents employed an exothermic nature to carry out the adsorption process. Up to five cycles of regeneration are possible for both adsorbents with little reduction in their effectiveness. Moreover, the possible adsorption mechanism reveals that the dye removal was carried out through π-π attraction, electrostatic interaction, and hydroxyl interaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One of the most precious resources in the universe is water. Without water, life cannot exist for most organisms living on earth. The human body is composed of approximately two-thirds water, emphasising its vital role in maintaining life1,2. Water contamination has become a significant global environmental issue, adversely affecting ecosystems and human health. In general, the term water pollution may be explained as introducing various unwanted materials into the water and causing adverse effects on the biological community3,4,5 Increasing industrialization, excessive dumpsites, urbanization, and poor agricultural management practices are some of the main human activities that worsen water pollution6,7,8,9,10,11,12.

Organic materials called dyes find numerous uses in industries like building, food, beverage, paper goods, ink for printing, cosmetics coatings, paints, polymers, and fabrics and plastics to color their products13,14. When used on an industrial scale, dyes are primarily categorized as anionic, cationic, and (disperse dyes) non-ionic15,16,17.

An anionic, long-lasting dye in the anthraquinone family is called alizarin red S (ARS). In the fabric sector, this dye is commonly used. It is a permanent, anionic dye member of the anthraquinone family. The fabric industry makes extensive use of this dye. Moreover, this dye stains biological samples like mineralized bones in vertebrates. Proper storage is required because this synthetic dye is a potent oxidizing agent. It has strong chemical and photolytic stability, which renders biodegradation ineffective. This complex structure makes the ARS dyes physically, chemically, and thermally stable. Due to its complex chemical structure, the complete degradation of ARS dye is highly challenging. Moreover, if it degrades, it will lead to some secondary pollutants that cause environmental carcinogenic and mutagenic effects18,19.

When the Dyes are discharged into the water, they block light penetration and deplete the DO, COD, BOD, and pH content, hindering the growth of aquatic organisms20. The contaminated water bodies can infiltrate fish or other marine organisms, that are then ingested by humans and carry on to cause long-lasting effects such as cramps, sporadic disorders, mutagenic, carcinogenic, and hypertension. Moreover, it affects the entire food chain of the aquatic system21.

So, eliminating this dye from the aqueous environment is essential because a trace level of dye can cause adverse health effects on all living beings. For the dye removal, a variety of physiochemical techniques, namely, coagulation and flocculation22, ion exchange23, photocatalysis24, electrocoagulation25, membrane filtration26, advanced oxidation process27, biological methods28, and adsorption methods29, are used. Compared with all other methods mentioned above, one of the more affordable and effective ways to remove contaminants from an aqueous solution is adsorption30,31,32,33. The significant limitations of using other methods for wastewater treatment include high operational costs, high capital costs, low efficiency, formation of secondary pollutants, high disposal costs, high maintenance costs, and excessive use of chemicals34,35,36,37.

Adsorption is an effect of the surface where pollutants hold onto the adsorbent’s surface due to interactions that can be chemical or physical38. A variety of adsorbents have been used for adsorption over the last few years, including biomass-based carbon39,40, zeolites41, Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOF)42, Chitosan43, nanoparticles44, magnetic nanocomposite45,46, Graphene oxide47,48, Saw dust49,50,51, activated alumina52, and silica gel53. Among these adsorbents, activated carbon prepared from agricultural waste biomass has gained more attraction. In general, agricultural biomass is lignocellulosic material that contains cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, and hydrocarbon. It also includes carboxyl, hydroxyl, nitro, etc. as functional groups. Because of being cost-effective and environmentally friendly, having specific chemical structures, and abundant availability, these materials are practical choices for remediating water and wastewater53,54,55,56,57. For activated carbon preparation, Hydrothermal carbonization (HTC) has gained significant observation in the context of the growing global issues in recent years. HTC is an economical method of thermally converting wet biomass to hydrochar58. Though this process is conducted in the water presence, it does not require pretreatment to eliminate the water content. It is one of the promising chemical pathways for treating raw materials due to its inherent benefits, namely a safer environment, adaptable chemistry, increased reaction rate, and cost-effectiveness59,60.

Persea americana Mill., the avocado tree, belongs to the Lauraceae family, and its edible fruit has a good economic significance61,62. This fruit can have an oblong, pear, or round shape, and its skin can have different colors and layers. This fruit has one large seed, making up more than 10% of its total weight63.

The avocado tree is consumed worldwide for various applications but is most commonly grown in Mexico and America. Every year, about six million tonnes of avocados are produced worldwide. It is most frequently used in the juice processing industries because of its high protein content and fat-soluble vitamins absent from other fruits. Because the pulp has varying oil levels, it is frequently utilized in the cosmetic and pharmaceutical industries. After obtaining the valuable products from the avocado, the residuals, like the avocado seeds, are thrown away into the environment, which may pollute the environment in an uncontrolled way64,65,66. So, these materials need proper disposal to overcome the problems associated with disposal. Rather than being disposed of, these materials can be further processed to develop some valuable products that can be utilized to address the issues associated with the environment.

This work uses avocado seed as a precursor for preparing the Hydrochar (HC) and Modified Hydrochar (MHC). HC was prepared from the raw avocado seed powder, while MHC was prepared from the sulphuric acid (H2SO4) Treated Avocado Seed Powder. As far as we are aware, the sequestration of ARS dye using Hydrochar using avocado biomass is not mentioned in any previous research works.

Materials and methods

Adsorbate synthesis

In this investigation, chemicals from the grades of analytical compounds were used. Alizarin Red S (ARS) dye of molecular weight of 360.28 g/mol, a wavelength of 424 nm, molecular formula of (C14H7NaO7S) was acquired with a standard grade from Sigma - Aldrich, India. The procured dyes were used for the experiments without any modifications. Chemicals, namely H2SO4 (98%), HCl (37%), and NaOH (97%) were procured from Merck Life Sciences Private Limited. 1000 milliliters of deionized water diluted with one gram of ARS dye produced a 1000 mg L−1 stock solution. The required concentration of the ARS dye will be attributed to successive dilution. The adsorption processes were evaluated using a U-V spectrophotometer of the JASCO V-630 model.

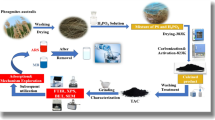

Preparation of adsorbents (HC and MHC)

Leftover avocado seeds were collected from a local juice shop in Kelambakkam, Chennai, India. To get rid of the contaminants, the seeds were repeatedly cleaned in distilled water. Afterward, it was sliced down into small pieces up to 4 mm and rewashed with distilled water. The powder underwent three hours of drying at 100 °C in an oven following consecutive rinses. Sulphuric acid was used for the activation of the adsorbent material through a wet oxidation process. The major reason for selecting sulphuric acid for the activation process was, that it can play a dual role like an oxidation and dehydrating agent. It promotes the oxygen-containing functional groups on the adsorbent surface to enhance the adsorption process. Additionally, it enhances the reactivity of the adsorbent material through the removal of the surface contaminants present on the adsorbent surface.

A 1:2 ratio of sulfuric acid was utilized in the wet oxidation process to activate the powder. Where the seed powder was impregnated in the acid solution for up to 12 h. After neutralizing the powder by washing it in distilled water, it was dried at 120oC. This Chemically Treated Avocado Seed Powder (CTASP) was kept in a tightly sealed container for later use.

Hydrochar (HC) was prepared using the Hydrothermal Carbonization (HTC). In this procedure, 5 g of raw avocado seed powder were mixed with 50 milliliters of double-distilled water to a 150-milliliter autoclave. Then, it was placed inside the Hot-air oven for 20 h at 150O C. After the stipulated time, the desired carbon samples were collected from the autoclave. Until the remaining solution lost all color, the gathered hydrochar was repeatedly cleaned with water. The samples were then dehydrated at 110 °C and kept in a sealed container for subsequent usage. Modified Hydrochar (MHC) preparation, the same procedure of Hydrochar synthesis through the Hydrothermal carbonization method was performed using the chemically treated carbon.

Characterization techniques

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (Perkin Elmer e L1600300, Llantrisant, UK) Within the 400–4000 cm−1 range was performed to analyze the various functional groups. An EVO18 Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) was used to examine the surface morphology of the HC and MHC adsorbents (Carl Zeiss). A TGA analysis (Make: NETZSCH, Model: NJA – STA 2500 Regulus) was conducted to examine the material’s thermal resistance. The pan in an oven or combustion chamber contains the sample material heated at 10oC min−1, ranging from room temperature to 100oC. The BET study was used to determine the surface area of the suggested materials (Quanta Chrome).

Batch adsorption experimental studies

In general, adsorption is the ability of the adsorbents to adsorb the pollutants on their surface through interactions. Batch adsorption studies were employed in the adsorption process to optimize the parameters involved. The wetness content in the HC and MHC were eliminated by placing them inside Hot air Oven at 120o for 2 h. In an orbital shaker, the necessary quantity of MHC and HC adsorbents were combined with the ARS concentration ranging from 50 mg/L to 250 mg/L for the designated duration at 303k. After filtering the leftover solution with the Whatman 42 filter paper, the remaining dye was measured using a UV spectrophotometer. To guarantee the consonant results, the adsorption procedure was repeated up to three times. The experiment’s equilibrium adsorption capacity (\(\:{q}_{e})\) and efficiency (η) were determined using the following formulas,

Where C0 and Ce represent the initial and final concentrations of the ARS (mg/L), in contrast, qe denotes the equilibrium adsorption capacity (mg/g−1).

Results and discussion

XRD evaluation

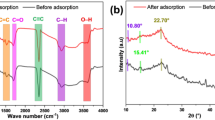

The XRD structure of hydrochar carbon obtained from avocado seed powder (precursor) via hydrothermal carbonization (HTC) exhibits a pattern range of 2θ = 20°−90°, which is displayed in Fig. 1. Noteworthy diffraction peaks are observed at angles (2θ) of 14.6, 23.32, 27.9, and 42.53 degrees in the XRD pattern, proving their amorphous and crystalline nature67,68. Among these peaks, 14.6, 23.32, and 27.69 degrees stand out; these three peaks are the peaks of cellulose. Because the peaks are positioned between 10° and 35° (2θ), this is explained by the amorphous carbon diffracting. Additionally, it indicates that the avocado seed powder was carbonized as carbon69,70. The weak peak at 42.53 confirmed the carbon structure formed with a disordered nature and this disordered carbon will have more surface area.

Modified hydrochar was synthesized using sulphuric acid-activated carbon as a precursor in the hydrothermal carbonization (HTC) method. From the XRD results, the obtained peaks are 20.59, 27.69, and 42.53, presenting an amorphous nature with small domain crystalline planes. The peak at 20.59 is a standard non-crystalline structure for the carbon and activated carbon71. The more substantial peak at 27.69 (2θ) explains the importance of the crystalline nature of the carbon and might be formed from its disordered diffractive nature of graphite72. The amorphous form of carbon is reflected by the faint and broad peaks at 42.53. This structure confirmed the formation of the carbon structure with a disordered nature. This disordered carbon will have more active sites and surface area, which will be responsible for the eradication of ARS dye in an effective manner73,74,75. MHC’s crystalline and amorphous efficiency is 14.6% and 85.4%, respectively. MHC is highly amorphous due to the precursor’s activation effect, and it will be helpful in the elimination of ARS. Compared with HC, MHC is more amorphous with less crystalline, and it will take part in the adsorption of ARS dye in an effective manner.

FT-IR analysis

The adsorption efficiency for eliminating ARS dye from the wastewater material is hugely dependent on the variety of functional groups. FTIR is also utilized to explore the material’s different chemical bonds. With the help of FT-IR spectroscopy, the possible adsorption mechanism through which the adsorption occurs was determined. In FTIR spectroscopy, the spectra ranges are recorded between 4000 cm−1 and 400 cm−1.

Figures 2 and 3 show the different spectra of Hydrochar (HC), which exhibits distinct absorption peaks associated with different functional groups. A peak shift at 3429–3437 cm−1 was observed both before and after adsorption. The presence of hydroxyl groups was confirmed by attributing these peaks and the small shifts to their O-H stretching vibration76. The weak peaks (O-H stretching) at 2946 cm−1 – 2888 cm−1 before adsorption was diminished in the after-adsorption, demonstrating the insertion of ARS molecules onto the HC surface77. A sharp peak shift from 1710 to 1742 cm−1 shows the presence of the Strong C = O78.

For the aromatic compounds, the peak displacement from 1642 cm−1 to 1633 cm−1 shows the presence of unsaturated stretching of lignin (C = C stretching vibration)79. Weak peaks of 1512 cm−1 before and following the ARS dye’s adsorption indicate the traces of nitro compound (N-O) present in the adsorbent80. A narrow stretching was obtained at 1456 cm−1 before and after adsorption, indicating an alkane group with C-H asymmetric vibrations81. The stretching at 1028 cm−1 and 1032 cm−1 indicates the existence of C-N82.

Figures 4 and 5 displays the FTIR spectra of the Modified Hydrochar (MHC) and ARS dye adsorbed on MHC. The broad peaks between 3438 cm⁻¹ and 3442 cm⁻¹ indicate the presence of hydroxyl groups76. The weak peaks include 2905 cm−1 – 2840 cm−1 and 3124 cm−1 – 3029 cm−1 showing the existence of a hydroxyl group and the absence of these peaks in the after-adsorption studies suggests the successful incorporation of ARS dye molecules77,78. The 1633 cm−1 – 1627 cm−1 peak shift indicates the presence of unsaturated stretching of lignin for the aromatic compounds (C = C)79. A sharp peak shift at 1710 cm−1 −1714 cm−1 shows the presence of strong indicates the appearance of the Strong C = O78.

The narrow stretching at 1510 cm−1 and 1456 cm−1, displays the availability of N-O groups and alkane groups with medium C-H bending80,81. The extreme C-N stretching is represented by the peak shifts from 1028 cm−1 to 1022 cm−1 and 1188 cm−1 to 1184 cm−182,83. The peak shift at 786 cm−1 – 779 cm−1 indicates the existence of a robust Carbon Hydrogen bond (C-H bending)84.

The primary and minor peak shift in the functional groups of HC and MHC FT-IR spectrum indicates the reaction of the ARS dye molecule on the adsorbent’s surface. Hence, it proves that the dye molecule was trapped on the adsorbent surface. The results display that HC and MHC adsorbents have essential functional groups: hydroxyl, Carbonyl, unsaturated hydrocarbon, alkane, and amine. The different interactions can be attributed to these functional groups: hydrogen bonds, covalent bonds, electrostatic attractions, ionic bonds, etc.

SEM analysis

It is a potent method for studying materials’ surface morphology and composition at a high resolution. The adsorption technique is majorly accomplished by the pores on the adsorbent’s surface. The amount of available pores on the adsorbent will determine how well the ARS dye can be adsorbed from the aqueous solution. Figures 6 display the SEM image of Hydrochar (HC) that highlights a melted and rougher surface with irregular pores. The hydrolysis and carbonization process broke down the organic compounds, specifically lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose material, in the biomass of avocado seed powder, producing these irregular pores in the Hydro Char surface85. Figure 7 displays the incorporation of ARS dye particles into the cavities of the HC surface. Removing methylene blue with hydrochar made from leftover coffee husk waste showed results that followed a similar pattern86. Fig. 8 displays the surface morphology of the Chemically Treated Avocado Seed Powder (CTASP) and Fig. 9 displays the surface morphology of Modified Hydrochar (MHC). The Modified Hydrochar (MHC) was obtained by hydrothermal carbonization of Chemically Treated Avocado Seed Powder (CTASP). The structure and surface characteristics of the activated carbon can be further altered by this process, resulting in the development of a well-developed pore structure. The presence of the micro and meso pores in the CTASP material was enhanced in MHC through hydrolysis and carbonization. Moreover, numerous tiny pores are also created due to the reaction of the HTC process. The developed pores are flaky and irregular. The trapped dye molecules on the MHC adsorbent’s pores are seen in Fig. 10. Similar outcomes were attained While using the different acid-pretreated hydrochars to remove Methylene Blue (MB) dye76.

EDS analysis

The EDS spectra of the HC and MHC adsorbents are displayed in Figs. 11, 12, 13 and 14. Tables 1 and 2 display the various components on the adsorbent’s surface. Among the two adsorbents, MHC has a higher carbon content due to the combination of acid activation and Hydrothermal carbonization87. The successful incorporation of ARS dye is demonstrated by the increased carbon content in the before and after adsorption of dyes in HC and MHC adsorbents. Aluminium, Silica, copper, calcium, sulphur, and iron were only in trace levels. In HC and MHC, other than carbon and oxygen content, the amount of nitrogen was high due to the Effect of hydrothermal carbonization.

BET adsorption isotherm studies

The Hydrochar (HC) and Modified Hydrochar (MHC) surface properties were analyzed through Quanta Chrome instruments. The samples (HC and MHC) weights of about 0.0810 g and 0.0890 g were examined through Quanta chrome Touch Win v1.24. Before the experiment, the specimens were degassed under a vacuum at 200o C for 6 h to remove all adsorbed impurities. After degassing, the samples were evenly dispersed inside the sample cell for further analysis. Nitrogen gas of high purity at different pressures and temperatures of 77.35 K was introduced into the sample, and the equilibrium adsorption taking place at various pressures was taken into account. Afterward, the desorption study was processed by reducing the pressure for evacuating the adsorbed nitrogen gas. The surface area of the material was evaluated through the adsorption and the desorption of the nitrogen gas at different pressure ranges.

Figures 15 and 16 displays the BET isotherm graph for HC and MHC adsorbents.

As shown in Table 3, the SSA of MHC was slightly higher than that of HC, likely due to the combined effect of chemical activation along with the hydrothermal carbonization process. Based on the IUPAC classification, the N2 adsorption and desorption isotherm of both HC and MHC systems obeys characteristic type IV and H3 hysteresis isothermal loop, which confirms that the nature of the adsorption system is a mesoporous structure88,89. The same pattern of results was obtained by Fengjuan Yang et al.90.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

Through the Thermogravimetric Analysis, the material’s thermal stability can be determined. Figures 17 and 18 display HC and MHC’s thermal degradation in three stages. The weight loss at the first stage in MHC (9%) and HC (14%) indicated the desorption of water or moisture content on the adsorbent surface. The second stage for HC (22%) and MHC (26%) shows the desorption of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOC) and cellulose and hemicellulose degradation. The final stage of decomposition includes the degradation of lignin and other carbon constituents present in HC (64%) and MHC (35%). Graph 18 shows that the MHC adsorbent was more stable than HC by displaying the remaining mass of about 30% after the degradation process. The concurrent activation of the adsorbent may improve the thermal stability (Chemical activation followed by HTC)91,92,93,94. The increased thermal stability in the MHC adsorbent is due to the partial removal of lignin and hemicellulose from the material during the sulphuric acid treatment95.

Point of zero charge

In adsorption, the Zero Point Charge plays a huge part in determining whether the surface of the adsorbent is protonated or deprotonated, or has a neutral charge. For the ZPC analysis, the drift method was used, and it is one of the most widely used methods96. For the pHZPC analysis, 12 conical flasks were taken (6 for HC and 6 for MHC) and filled with 0.01 M of NaOH (residual solution). With the buffer solution, the pH variety of all those conical flasks was adjusted to between 2 and 12. After adding 0.2 g of HC and MHC adsorbents, these conical flasks were shaken at 120 rpm for a full day. After the stipulated time intervals, the residual solution was filtered and the pH of the filtrate was evaluated. Then, a graph of ∆pH (change in pH) vs. pH (original pH) was plotted for both the adsorbents. The pHZPC was ascertained by locating the graph’s intersection of the pH vs. ∆pH plot. Figures 19 and 20 show that the zero point charges of HC and MHC adsorbents were 6.85 and 6.92. Thus, the pH at which the adsorbent surface carries no net charge was determined.

Effect of contact time

Generally, the dye removal efficiency and the contact time are directly proportional to each other up to an equilibrium condition, that is the removal efficiency keeps on increasing up to the equilibrium time97. The impact of the ARS dye removal by HC and MHC adsorbents was assessed by ranging the contact time from 10 min to 60 min and the dye concentrations ranged from 50 to 250 mg/L. The other adsorption parameters, such as pH 2, dose rate 0.2 g and 0.1 g (HC and MHC), and temperature 30 °C, were kept constant. The effect of the shaking time was graphically represented in Figs. 21 and 22. It is evident from the figures that, there was a discernible rise in the elimination of dye molecules up to 30 min, and after 30 min there was a gradual decline in the elimination of ARS dye particles in both HC and MHC adsorbents. To put it another way, before 30 min, the ARS dye molecules will have more accessible active sites to connect to the adsorbent surface; however, after 30 min, the active sites are filled with ARS dye molecules. A similar pattern of results was obtained in the elimination of ARS dye with Delonix regia pods98.

Effect of initial concentration

To analyze the effect of initial concentration, the concentration of the dye was varied from 50 mg/L and 250 mg/L, and the other parameters of pH 2, time, temperature, and adsorbent dosage at 0.2 and 0.1 g (HC and MHC) were kept constant. Figure 23 displays the removal efficiency of ARS dye using MHC and HC adsorbents. It is clear from the figure that the adsorption efficiency of the ARS dye molecules decreases from 99.92% to 89.41% for MHC and 99.81%–79.71% for HC while increasing the concentration of ARS dye. At higher ARS concentrations, a more significant number of ARS dye molecules will compete for the fixed active sites and thereby causing a reduction in the adsorption efficiency. Despite operating under varying initial dye concentrations, the adsorbent’s constant active sites eliminate the predetermined quantity of dye molecules. The elimination of Rhodamine-B from an aqueous solution on parthenium carbon (PWC) treated with phosphoric acid and parthenium biomass (WC) treated with formaldehyde follows a similar pattern99.

Impact of the solution pH

The impact on the pH of ARS dye efficiency on HC and MHC adsorbents was determined by changing the pH range from 2 to 10. The other parameters like adsorbent dosage (HC and MHC) 0.2 and 0.1 g, shaking time 60 min, Temperature 30oC, and ARS dye concentration 50 mg/L were kept constant. Figure 24 displays the percentage removal of ARS molecules at varying pH and it clearly shows the decrease in the efficiency of the ARS dye while increasing the pH range from 2 to 10. Maximum ARS dye removal of 99.81% and 99.92% for HC and MHC were obtained at a pH of 2 and it displays that the adsorption process obeys acidic pH. Because of the sulfonic acid group in its structure, the ARS dye has an adverse charge in an aqueous solution. The pH ZPC of the adsorbents (HC and MHC) were found to be 6.85 and 6.81 using the drift method. Therefore, MHC and HC adsorbents exhibit a positive charge at pH 2 (pH < PHZPC. Thus, the primary reason behind the increased adsorption efficiency at pH 2 is the electrostatic attraction between ARS dye molecules and the adsorbent surface (HC and MHC). From the pH range of 2–10, the adsorption efficiency of the HC and MHC adsorbents decreased from 99.81% − 33.08% and 99.92% – 27.55%. Because negatively charged dye molecules and negatively charged adsorbents (HC and MHC) repel one another electrostatically, the adsorption efficiency decreases. A similar pattern was observed when Congo red dye molecules were removed using raw and acid-activated pine cone powder biomass100.

Impact of HC and MHC dosages

For this evaluation, the dosages ranged from 0.5 to 3 g for HC and 0.25–2 g for MHC. The other adsorption-influencing parameters were kept constant. From Figs. 25 and 26, it is clear that the ARS dye molecule removal efficiency was increased from 37.59% to 99.91% for HC and 63.69% − 99.96% for MHC with an increased dosage. The higher removal efficiency of ARS dye molecules on increasing the MHC and HC dosage. The reason for the improvement in adsorption effectiveness when the dosage is increased is the availability of more surface area. The equilibrium was attained at 0.2 g and 0.1 g for HC and MHC adsorbents. After attaining the equilibrium stage, increasing the HC and MHC dosage does not enhance the adsorption efficiency. There will not be any more ARS dye molecules to adhere to the HC and MHC adsorbents at the fixed ARS dye concentration. MHC adsorbent has an increased surface area than HC adsorbent, which is the primary reason for the increased adsorption efficiency of MHC adsorbent. The elimination of the ARS dye molecule using a biomass fly ash-based adsorbent showed a similar pattern of results101.

Impact of temperature

The effect of temperature on ARS removal through HC and MHC was determined by changing the adsorption process temperature ranging from 303 K to 333 K. The other relevant factors were maintained constant at the same moment. Figures 27 and 28 display the percentage removal of ARS dye with varying temperatures. From the statistics, it is clear that the increasing temperature was not a suitable condition for the dye removal. The major rationale behind the decreased removal efficiency at the lower temperature is that at lower temperatures (303 K) the kinetic energy is also low, so there will be an increased adsorption efficiency, because of the significant magnetic attraction among the protonated adsorbents (HC and MHC) and deprotonated ARS dye molecules102. When the temperature starts to increase from 303 K, the kinetic energy also increases. Thus, it Favors the strong electrostatic repulsion between the protonated adsorbents (HC and MHC) and deprotonated ARS dye molecules. So, when the temperature increases the ARS dye molecules will rapidly be desorbed from the adsorbent surface. When Monotheca buxifolia waste seeds made from activated carbon were used to remove ARS dye molecules, a similar pattern in the results were seen102.

Thermodynamic studies

The thermodynamic characteristics were examined by the application of thermodynamic parameters, specifically Gibbs free energy (∆G), enthalpy (∆H), and entropy (∆S). These investigations were often conducted to look at the adsorption process’s viability, its exothermic or endothermic character, and its degree of randomness or disorderliness103. To do this analysis, the temperature was changed from 303 K to 333 K and the ARS dye concentration was varied from 50 mg/L to 250 mg/L. The other parameters including pH, dosage, and contact time are kept constant. The following equations (1 to 5) can determine the Gibbs free energy, Enthalpy, and Entropy,

The variables CAe, Ce, T, R, and Kc represent the quantity of adsorbate adsorbed on the adsorbent surface at (mg/L), the equilibrium concentration of ARS dye in an aqueous medium (mg L−1), the temperature (K), the universal gas constant (8.314 J/mol/K) and equilibrium constant, respectively.

Tables 4 and 5 contain the thermodynamic parameters obtained from Figs. 29 and 30. From the Tables, the adsorption may be spontaneous, because both HC and MHC have Gibbs free energy values in negative terms. The negative value of Enthalpy for both of the adsorbents (HC and MHC) suggests that the process is exothermic, that is energy is liberated during the adsorption process. The negative Entropy indicates a decline in the randomness or disorderness of the process for both of the adsorbents. Additionally, the decrease in randomness indicates an intense relationship between the adsorbents and the adsorbate molecule. When ARS dye was removed using Fe3O4@NiO-based magnetic nanoparticles, similar trends in the results were seen104.

Adsorption isotherm studies

Adsorption isotherms, in general, explain the adsorbates’ retention, release, and mobility on the solid material at a constant temperature after being added to an aqueous solution. They are important for comprehending the adsorption mechanisms. The adsorption efficiency of the adsorption process can be obtained with the contribution of adsorption isotherm studies only105,106. The Langmuir adsorption isotherm model is majorly utilized to evaluate surface interaction. The adsorption process in this model is limited to the monolayer and assumed to have a homogeneous surface.

Langmuir adsorption isotherm model107 is stated mathematically as below,

The values of Ce, qm, and qe represent the equilibrium concentration, adsorption capacity, and amount of dye adsorbed at equilibrium, in mg L−1, mg g−1, and mg/g. Where KL (L/mg) denotes the Langmuir isotherm constant.

Another variant of the Langmuir adsorption isotherm is the Freundlich isotherm model, where a multilayer adsorption process takes place. It can be explained as follows108:

The Freundlich coefficient, n, is used to determine the adsorption strength. The Freundlich constant is represented by the notation KF [(mg g−1) (L mg−1)1/n].

The Temkin isotherm model indicates that because of interactions between the adsorbent and adsorbate during adsorption, the adsorption heat of all the layers falls linearly with uptake.

The Temkin isotherm model109 can be mathematically explained below,

where,

The variables B, R, T, and AT are related to the heat of adsorption (J/mol), temperature (K), Temkin isotherm constant (bT), and Temkin isotherm equilibrium binding constant (L/mg).

The three-parameter Redlich-Peterson isotherm model is an empirical model that combines the characteristics of Freundlich’s adsorption and Langmuir’s110,111.

At high concentrations, it approaches the Freundlich model and is compatible with the low-concentration limit of the Langmuir equation. The mathematical representation of this paradigm is written like this,

where KR (L/g) and αR (L/mg) denote the Redlich–Peterson isotherm constant, and β is the dimensionless exponent term linked to the adsorption intensity, which is a range of 0 to 1. This exponent can predict the adsorption isotherm in the following ways: if β = 1, the system follows the Langmuir model; otherwise, the Freundlich model describes the system112. Figures 31 and 32 show the isotherm studies’ graphical representation.

The model with the highest R2 values and the lowest error values was found to be appropriate for the isotherm investigations. For the two adsorbents, the Freundlich isotherm model has a higher R2 value and minimal error value (Tables 6 and 7, respectively). So, it is observed that the HC and MHC adsorbents obey the Freundlich model for the elimination of ARS. The recommended adsorbents were found to have an adsorption capacity of 231.6 mg/g for MHC and 97.51 mg/g for HC. When comparing the adsorbents, the MHC adsorbent exhibits a greater capability for adsorption and this may be due to the combined chemical and Hydrothermal activation.

The obtained separation factor (RL) value of HC (0.050 to 0.010) and MHC (0.049 to 0.010) adsorbents falls between the range of 0 to 1, suggesting the favourability nature of the adsorption. The ‘n’ values of 4.339 (HC) and 3.791 (MHC) were calculated and listed in Tables 6 and 7. For all the adsorbents, the ‘n’ value falls between 0 and 10, suggesting that the system obeys physisorption for both adsorbents. According to the Temkin model, the system is also subject to physisorption, which occurs when the heat of adsorption is less than 8 kJ/mol.

From the Redlich-Peterson adsorption isotherm results, the β value of HC (0.7696) and MHC (0.7362) falls less than 1. It suggests that various active sites on the surface of the HC and MHC adsorbents have different affinity towards the ARS dye molecules. According to the results displayed in Tables 6 and 7, the system obeys the Freundlich adsorption isotherm model for HC and MHC adsorbents.

A comparison of HC and MHC adsorbents’ adsorption capability with already available adsorbents is listed in Table 8. It is clear from the table that the prepared adsorbents have better adsorption capacity and, in the future, they may be commercialized for the elimination of ARS from industrial sources.

Adsorption kinetic studies

In an adsorption process, the adsorption kinetic models play a significant role by providing basic details about the mass transfer mechanisms, the adsorbent’s efficacy, and the rate of the adsorption. It also describes the rate at which dye molecules are retained and released. In general, the adsorption kinetics was used to evaluate the nature (physical or chemical adsorption) of the adsorption. It was evaluated by different models that include the Pseudo-first order122, Pseudo-second order123, and Elovich124 models, and their mathematical equations are given as follows,

Where qe is the amount of adsorbate adsorbed at equilibrium conditions (mg g−1), qt is the adsorption capacity at a specific time t (mg/g), k1 and k2 are the kinetic rate constants (min−1), α is the initial adsorption rate(mg/g.min) and β is the elovich isotherm constant (g/mg).

The kinetic models’ graphical representation (qt vs. t) using MATLAB 2019 b is shown in Figs. 33 and 34 (for HC and MHC). The kinetic parameters (Regression coefficient) R2, SSE, and RMSE) are displayed in Tables 9 and 10.

The best-suited model for this adsorption kinetic system can be evaluated by comparing the experimental and calculated equilibrium adsorption (qe cal vs. qe exp) capacity values. From the results in Tables 9 and 10, it is evident that the PFO model has calculated adsorption capacity (qe cal) values more or less equal to qe exp for both HC and MHC adsorbents compared with other kinetic models. Also, the PFO model has a higher R2 value with low error values (SSE and RMSE) for both HC and MHC adsorbents. So, it was concluded that the PFO model is the more-suited model for this system and the elimination of ARS dye molecule using HC and MHC adsorbent has occurred through physisorption.

Diffusion mechanism

Taking into consideration that, the adsorption process was well suited to the physisorption model, it is necessary to evaluate the impact of mass transfer resistance,

The three stages of the adsorption process include.

-

Film Diffusion.

-

Internal diffusion.

-

Adsorption.

The Film diffusion can be explained as the entry of the adsorbates from the bulk solution to the outer region of the adsorbent. Internal diffusion is the movement of dye molecules from the exterior part to the internal region of the adsorbent. Finally, the attachment of these molecules to the pores on the adsorbent occurs through adsorption. This adsorption process is carried out through a weak or strong bond. For any system, the adsorption process is considered to be a rapid step. So, it was omitted for determining the rate-limiting step. Therefore, it’s important to ascertain whether internal or film diffusion controls the entire adsorption process.

The models namely the Weber & Morris intraparticle diffusion125 and Boyd’s kinetic model126, were used to analyze the possible diffusion mechanism.

Intra particle diffusion model can be expressed as follows,

where C is termed to be the intercept, and Kp (mg/gmin1/2) is the rate constant and it was determined by plotting a graph between qt vs. t1/2. The boundary layer effect is observed in the plot’s intercept. A larger intercept value will result in an increased level of thickness in the outer layer and that majorly affects the diffusion rate in the system. If the system has an intercept value of zero, the system’s rate is exclusively governed by the diffusion of intraparticle.

The results including R2 and intraparticle diffusion coefficients obtained for the MHC and HC adsorbent were tabulated in Tables 11 and 12. The graphical representation of the intraparticle diffusion model for the MHC and HC adsorbent is shown in Figs. 35 and 36. For the system to obey the intraparticle diffusion model, the plot of qt vs. t1/2 must be linear and it needs to cross through the origin. In our instance, as seen in Figs. 35 and 36, the plot’s linearity and lack of crossing the origin suggested that the system was not being controlled by the internal diffusion of either adsorbent.

Additionally, the Boyd kinetic model allows for additional discussion of the rate-limiting stage in the adsorption process. The mathematical expression for this model can be expressed as follows,

In this case, Bt is the function of F, and F is defined as the percentage of adsorbates adsorbed at any given time interval “t.” It is possible to rewrite Eq. (16) as follows.,

For the Boyd kinetic model analysis, the graph was plotted (Bt vs t) and it was displayed in Figs. 37 and 38. The data obtained through the Boyd kinetic model were tabulated in Tables 11 and 12.

It is clear that the plot was linear and did not cross through the origin from Figs. 37 and 38. This demonstrates that the rate-limiting phase in the adsorption of the ARS dye molecule through HC and MHC adsorbents was film diffusion.

Possible adsorption mechanism

-

The FT-IR data suggests that the process of employing hydrochar (HC) to remove Alizarin Red S dye (ARS) from wastewater might include the creation of hydrogen bonds between the hydroxyl groups on HC’s surface and the ARS dye molecules. Since weak peaks linked to O-H stretching vibrations (2946 cm−1 to 2888 cm−1) dissipate before adsorption, this may result in a successful absorption of ARS dye molecules onto the surface of HC. Furthermore, a sharp peak shift in the Strong C = O stretching vibration of the carbonyl group (1710 cm−1 to 1742 cm−1) indicates that the carbonyl groups of ARS and HC are chemically interacting. These interactions indicate the successful adsorption of ARS molecule on HC surface.

-

The FT-IR data suggests that the process of employing Modified Hydrochar (MHC) to remove Alizarin Red S dye (ARS) from wastewater might include the creation of hydrogen bonds between the hydroxyl groups on MHC’s surface and the ARS dye molecules. The weak peaks include 2905 cm−1 – 2840 cm−1 and 3124 cm−1 – 3029 cm−1 showing the existence of a hydroxyl group and the absence of these peaks in the after-adsorption studies suggests the successful incorporation of ARS dye molecules. Furthermore, the emergence of peak shifts in the carbonyl groups points to a strong C = O stretching vibration (1710 cm−1 to 1714 cm−1), suggesting potential chemical interactions between the carbonyl groups of ARS and MHC. This helps MHC to adsorb the ARS dye from wastewater. The graphical representation of the adsorption mechanism for HC and MHC is displayed in Fig. 39.

Effect of co-ions

For the effective utilization and commercialization of the HC and MHC adsorbents, the impact of the counterions on the selective removal of ARS dye molecules using HC and MHC adsorbents plays a major role. So, in this study, inorganic salts namely Chloride (Cl−), Fluoride (F−), Sulphate (SO42−), and Nitrate (NO3), were used to analyze the selective removal of HC and MHC adsorbents. For this analysis, 50 mg/L of ARS dye solution was taken along with the 50 mg/L of Chloride, Fluoride, Sulphate and Nitrate. The results (Fig. 40) show that the presence of these ions in the water will reduce the removal efficiency by a considerable amount. The major reason behind the decline in removal efficiency may be due to the competitive adsorption between the counterions and the ARS dye molecules, Electrostatic repulsion, higher charge density, and selective adsorption.

Regeneration studies

Generally, the used adsorbents were disposed of into the environment as waste material. These spent adsorbents are more hazardous to dispose of and require some major disposing techniques like incineration, which requires huge energy and cost. Dumping this material into the environment also causes serious environmental threats. To overcome these problems, the regeneration of these spent adsorbents can be done. The major advantage of the regeneration process includes that, it will enhance the stability of the spent adsorbent and valuable adsorbates can be recovered through the regeneration process. In this study, NaOH is used as an eluting agent for the recovery of the spent adsorbent. For the regeneration analysis, HC and MHC adsorbents are saturated with 50 mg/L of ARS dye solution for the stipulated time. After the stipulated time interval, 0.1 M of NaOH solution was used to desorb the dye molecules saturated in both adsorbents. The alkalinity of the NaOH molecule will disturb the interactions (electrostatic and hydrogen bonding) between the adsorbent surface (HC and MHC) and the ARS dye molecules. In this way, the adsorbed molecule starts to desorb from the adsorbent surface. After the desorption process, the adsorbent was washed and Oven dried at 150 degrees Celsius for 120 min. Then these regenerated adsorbents can be used again and again for up to 5 cycles with the regeneration efficiency ranging from 95% − 74% for MHC and 92% −58% for HC adsorbent. The regeneration efficiency of the HC and MHC adsorbents was graphically displayed in Fig. 41. It is observed that both HC and MHC adsorbents can be successfully regenerated for up to 5 cycles with minimum losses in their efficiency. Among the adsorbents, the MHC adsorbent shows better removal efficiency in regeneration than the HC adsorbent. Specifically, MHC maintained an efficiency of approximately 74% after the fifth cycle, whereas HC exhibited a decline to around 58%. The efficiency loss in successive cycles may be due to the physical and chemical changes and loss of functional groups on the surface of the adsorbents127. The removal of ARS dye using the Pine cone biomass and the Chemically treated avocado seed powder follows a similar pattern, where the regeneration efficiency was maximum at the first cycle and it keep on decreasing in the successive cycles120,128.

Conclusion

In this study, two cost-effective and eco-friendly adsorbents namely, Hydrochar (HC) and Modified Hydrochar (MHC) were successfully synthesized through Hydrothermal carbonization and chemical activation combined with hydrothermal carbonization. Then the synthesized adsorbents were employed to eliminate the Alizarin Red S (ARS) dye from the water environment. From the characterization studies, the FT-IR analysis displays that the HC and MHC adsorbent surface was composed of functional groups, namely Hydroxyl, Carbonyl, unsaturated stretching of lignin, Nitro compound, alkane, and amine. SEM analysis displays that the surface of the HC adsorbent shows a melted and rougher surface with irregular pores and it also has a significant amount of carbon content to entrap the ARS dye molecule. On the other hand, the surface of the MHC adsorbent has some flaky and irregular pores. Moreover, the surface of the MHC has a well-developed pore structure due to the combined activation of chemical and hydrothermal carbonization. XRD analysis shows that both HC and MHC adsorbents are amorphous with slight crystallinity. The crystallinity nature was formed due to the graphitic carbon diffraction. TGA studies show that the MHC adsorbent has more thermal stability when compared with the HC adsorbent due to the combined chemical and hydrothermal activation. BET analysis shows that MHC and HC adsorbents have a surface area of 23.435 m2/g and 14.519 m2/g. The pore diameters of MHC and HC were measured as 3.05489 nm and 3.06075 nm, respectively. The pore diameter for these materials falls between 2 and 50 nm, indicating that the prepared materials are mesopores. The surface of the HC and MHC adsorbent has no charge and it was estimated through the drift method. The batch adsorption studies are used to evaluate the ideal conditions for the batch study parameters, where the maximum removal will occur. For the HC and MHC adsorbents, a pH of 2, a contact time of 30 min, an initial concentration of 50 mg/L, and a temperature of 303 K was finalized as a favorable condition for the adsorption.

The co-ions study was also analyzed to evaluate the selective removal of ARS dye molecules on HC and MHC adsorbents in the presence of some counter ions. The co-ions results display that HC and MHC adsorbents have better selectivity in the removal of targeted pollutants with minimal loss in efficiency. Two-parameter and three-parameter isotherm models namely Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin, and Redlich Peterson isotherm models were used to analyze the nature of the adsorption. In this study for both HC and MHC adsorbents, the system obeys Freundlich adsorption isotherm (Multilayer). The rate of the adsorption process was analyzed through the kinetic models and the system obeys the Pseudo-First Order for both adsorbents. The diffusion mechanism was analyzed through Intra Particle Diffusion and the Boyd kinetic model. The results revealed that for this adsorption process, the rate of the reaction was controlled by film diffusion for both adsorbents. The thermodynamic studies show that the adsorption process was spontaneous, exothermic, and with decreased disorderliness for both adsorbents. According to the regeneration studies, there is little to no efficiency loss when both adsorbents are regenerated up to five times. The MHC adsorbent shows better regeneration efficiency than the HC adsorbent. Overall, MHC demonstrated superior performance compared to HC across all parameters.

Limitations and future prospectives

-

The main drawbacks of biomass-related adsorbents are their reduced adsorption capacity, slower kinetics, pollutant selectivity, sensitivity to environmental factors, and stability, these drawbacks can be overcome in the future by a variety of doping agents, such as metal-organic framework, nanoparticles, metal ions, graphene oxide, and carbon nanotubes.

-

Combining the adsorption process with other treatment methods such as membrane filtration, oxidation, or biological processes may enhance overall efficiency and effectiveness.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Hosny, N. M., Gomaa, I. & Elmahgary, M. G. Adsorption of polluted dyes from water by transition metal oxides: A review. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 15, 100395 (2023).

Chaplin, M. F. Water: its importance to life. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ. 29 (2), 54–59 (2001).

Tee, G. T., Gok, X. Y. & Yong, W. F. Adsorption of pollutants in wastewater via biosorbents, nanoparticles and magnetic biosorbents: A review. Environ. Res. 212, 113248 (2022).

Awad, A. M. et al. Adsorption of organic pollutants by nanomaterial-based adsorbents: An overview. Journal of Molecular Liquids, 301, p.112335. (2020).

Awad, A. M. et al. Adsorption of organic pollutants by natural and modified clays: a comprehensive review. Separation and Purification Technology, 228, p.115719. (2019).

Dotto, G. L. & McKay, G. Current scenario and challenges in adsorption for water treatment. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 8(4), p.103988. (2020).

Garg, M. Water pollution in India: causes and remedies. Int. J. Phys. Social Sci. 2 (6), 555–567 (2012).

Ado, A. et al. A review on industrial effluents as major sources of water pollution in Nigeria. Chem. J. 1 (5), 159–164 (2015).

Pooja, D., Kumar, P., Singh, P. spsampsps Patil, S. (eds) Sensors in Water Pollutants Monitoring: Role of Materialp. 320 (Springer, 2020).

Akhtar, N., Ishak, S., Bhawani, M. I. & Umar, K. S.A. and Various natural and anthropogenic factors responsible for water quality degradation: A review. Water, 13(19), p.2660. (2021).

Köck-Schulmeyer, M. et al. Occurrence and behavior of pesticides in wastewater treatment plants and their environmental impact. Sci. Total Environ. 458, 466–476 (2013).

Jameel, A. T., Muyubi, S. A., Karim, M. I. A. & Alam, M. Z. Removal of oil and grease as emerging pollutants of concern (EPC) in wastewater stream. IIUM Eng. J., 12(4). (2011).

Gürses, A. et al. Classification of dye and pigments. Dyes Pigm., pp.31–45. (2016).

Affat, S. S. Classifications, advantages, disadvantages, toxicity effects of natural and synthetic dyes: A review. Univ. Thi-Qar J. Sci. 8 (1), 130–135 (2021).

Benkhaya, S., M’rabet, S. & El Harfi, A. A review on classifications, recent synthesis and applications of textile dyes. Inorganic Chemistry Communications, 115, p.107891. (2020).

Rajabi, M., Mahanpoor, K. & Moradi, O. Removal of dye molecules from aqueous solution by carbon nanotubes and carbon nanotube functional groups: critical review. RSC Adv. 7 (74), 47083–47090 (2017).

Adegoke, K. A. & Bello, O. S. Dye sequestration using agricultural wastes as adsorbents. Water Resour. Ind. 12, 8–24 (2015).

Gautam, R. K., Mudhoo, A. & Chattopadhyaya, M. C. Kinetic, equilibrium, thermodynamic studies and spectroscopic analysis of Alizarin red S removal by mustard husk. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 1 (4), 1283–1291 (2013).

Machado, F. M. et al. Adsorption of Alizarin red S dye by carbon nanotubes: an experimental and theoretical investigation. J. Phys. Chem. C. 120 (32), 18296–18306 (2016).

Al-Tohamy, R. et al. A critical review on the treatment of dye-containing wastewater: Ecotoxicological and health concerns of textile dyes and possible remediation approaches for environmental safety. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 231, p.113160. (2022).

Selvaraj, V., Karthika, T. S., Mansiya, C. & Alagar, M. An over review on recently developed techniques, mechanisms and intermediate involved in the advanced azo dye degradation for industrial applications. Journal of molecular structure, 1224, p.129195. (2021).

Jiang, J. Q. The role of coagulation in water treatment. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 8, 36–44 (2015).

Kansara, N., Bhati, L., Narang, M. & Vaishnavi, R. Wastewater treatment by ion exchange method: a review of past and recent researches. ESAIJ (Environmental Sci. Indian Journal). 12 (4), 143–150 (2016).

Ahmed, S. N. & Haider, W. Heterogeneous photocatalysis and its potential applications in water and wastewater treatment: a review. Nanotechnology, 29(34), p.342001. (2018).

Tahreen, A., Jami, M. S. & Ali, F. Role of electrocoagulation in wastewater treatment: A developmental review. Journal of Water Process Engineering, 37, p.101440. (2020).

Konvensional, B. T. A review of oilfield wastewater treatment using membrane filtration over conventional technology. Malays J. Anal. Sci. 21, 643–658 (2017).

Miklos, D. B. et al. Evaluation of advanced oxidation processes for water and wastewater treatment–A critical review. Water Res. 139, 118–131 (2018).

Bhatia, D., Sharma, N. R., Singh, J. & Kanwar, R. S. Biological methods for textile dye removal from wastewater: A review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47 (19), 1836–1876 (2017).

Rashid, R., Shafiq, I., Akhter, P., Iqbal, M. J. & Hussain, M. A state-of-the-art review on wastewater treatment techniques: the effectiveness of adsorption method. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 9050–9066 (2021).

Karimi-Maleh, H. et al. Recent advances in using of chitosan-based adsorbents for removal of pharmaceutical contaminants: A review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 291, p.125880. (2021).

Djilani, C. et al. Adsorption of dyes on activated carbon prepared from apricot stones and commercial activated carbon. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 53, 112–121 (2015).

Atmani, F., Kaci, M. M., Akkari, I., Yeddou-Mezenner, N., Bensaadi-Ouznadji, Z., Balamane-Zizi,O., … Mokhati, A. (2024). Adsorption ability of sugar scum as industrial waste for crystal violet elimination: Experimental and advanced statistical physics modeling.Surfaces and Interfaces, 54, 105166.

Kaci, M. M., Akkari, I., Pazos, M., Atmani, F. & Akkari, H. Recent trends in remediating basic red 46 dye as a persistent pollutant from water bodies using promising adsorbents: a review. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy, 1–16. (2024).

Verma, A. K., Dash, R. R. & Bhunia, P. A review on chemical coagulation/flocculation technologies for removal of colour from textile wastewaters. J. Environ. Manage. 93 (1), 154–168 (2012).

Charles, J. et al. Pollutant removal from industrial discharge water using individual and combined effects of adsorption and ion-exchange processes: chemical abatement. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 20 (2), 185–194 (2016).

Uddin, M. K. A review on the adsorption of heavy metals by clay minerals, with special focus on the past decade. Chem. Eng. J. 308, 438–462 (2017).

Tiliouine, Y. et al. Powdered Myrtle leaves: A sustainable biosorbent for effective methylene blue adsorption. Water Conserv. Sci. Eng. 9 (1), 31 (2024).

Wang, J. & Guo, X. Adsorption isotherm models: Classification, physical meaning, application and solving method. Chemosphere, 258, p.127279. (2020).

Nizam, N. U. M., Hanafiah, M. M., Mahmoudi, E., Halim, A. A. & Mohammad, A. W. The removal of anionic and cationic dyes from an aqueous solution using biomass-based activated carbon. Scientific Reports, 11(1), p.8623. (2021).

Solanki, A., Ahamad, Z. & Gupta, V. Upcycling waste biomass: Alkali-modified watermelon rind as a lignocellulosic bioadsorbent for copper ion removal. Ind. Crops Prod. 224, 120340 (2025).

Jiang, N., Shang, R., Heijman, S. G. & Rietveld, L. C. High-silica zeolites for adsorption of organic micro-pollutants in water treatment: A review. Water Res. 144, 145–161 (2018).

Rojas, S. & Horcajada, P. Metal–organic frameworks for the removal of emerging organic contaminants in water. Chem. Rev. 120 (16), 8378–8415 (2020).

Wang, J. & Zhuang, S. Removal of various pollutants from water and wastewater by modified Chitosan adsorbents. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47 (23), 2331–2386 (2017).

Wang, J. et al. Preparation and excellent adsorption of water pollution dyes over magnetic Fe3O4/C nanoparticles with Hollow grape cluster morphology. J. Nanopart. Res. 22, 1–11 (2020).

Ahamad, Z. & Nasar, A. Polypyrrole-decorated bentonite magnetic nanocomposite: A green approach for adsorption of anionic Methyl orange and cationic crystal Violet dyes from contaminated water. Environ. Res. 247, 118193 (2024).

Ahamad, Z., Mashkoor, F., Nasar, A. & Jeong, C. Multi-walled carbon nanotubes/TiO2/Chitosan nanocomposite for efficient removal of malachite green dye from aqueous system: A comprehensive experimental and theoretical investigation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 295, 139461 (2025).

Tara, N. et al. Graphene, graphene oxide, and reduced graphene oxide-based materials: a comparative adsorption performance. In Contamination of Water (495–507). Academic. (2021).

Ahamad, Z., Bhat, A. S. & Nasar, A. High-performance magnetic graphene oxide/alginate hydrogel for efficient malachite green removal. J. Water Process. Eng. 70, 107024 (2025).

Ahamad, Z. & Nasar, A. Utilization of Azadirachta indica sawdust as a potential adsorbent for the removal of crystal Violet dye. Sustainable Chem. 4 (1), 110–126 (2023).

Ahamad, Z., Ahmed, M., Mashkoor, F. & Nasar, A. Chemically modified Azadirachta indica sawdust for adsorption of methylene blue from aqueous solutions. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery. 14 (16), 19929–19946 (2024).

Ahamad, Z. & Nasar, A. Synthesis, characterization, and application of magnetized Azadirachta indica sawdust as a novel adsorbent: kinetic, and isotherm studies in removing methylene blue as a model dye. Cellulose 31 (6), 3763–3782 (2024).

Szatyłowicz, E. & Skoczko, I. Studies on the efficiency of Grundwater treatment process with adsorption on activated alumina. J. Ecol. Eng., 18(4). (2017).

Guo, S. et al. Zn (II), Pb, I. I. and Cd (II) adsorption from aqueous solution by magnetic silica gel: preparation, characterization, and adsorption. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 25, 30938–30948 (2018).

Bhatnagar, A. & Sillanpää, M. Utilization of agro-industrial and municipal waste materials as potential adsorbents for water treatment—a review. Chem. Eng. J. 157 (2–3), 277–296 (2010).

Thitame, P. V. & Shukla, S. R. Adsorptive removal of reactive dyes from aqueous solution using activated carbon synthesized from waste biomass materials. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 13, 561–570 (2016).

Mo, J. et al. A review on agro-industrial waste (AIW) derived adsorbents for water and wastewater treatment. J. Environ. Manage. 227, 395–405 (2018).

Khan, S., Ahamad, Z. & Nasar, A. Development and utilization of Raw and NaOH-modified peanut hull as potential adsorbents for crystal Violet dye removal from wastewater. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery. 15 (3), 4025–4045 (2025).

Khatoon, H. & Rai, J. P. N. Agricultural waste materials as biosorbents for the removal of heavy metals and synthetic dyes-a review. Octa J. Environ. Res., 4(3). (2016).

Nguyen, T. A. H. et al. Applicability of agricultural waste and by-products for adsorptive removal of heavy metals from wastewater. Bioresour. Technol. 148, 574–585 (2013).

Akkari, I. et al. NaOH-activated pomegranate Peel hydrochar: preparation, characterization and improved Acebutolol adsorption. Water Air Soil Pollut. 234 (11), 705 (2023).

Seymour, G. B. & Tucker, G. A. Avocado. In Biochemistry of Fruit Ripening 53–81 (Springer Netherlands, 1993).

Araújo, R. G., Rodriguez-Jasso, R. M., Ruiz, H. A., Pintado, M. M. E. & Aguilar, C. N. Avocado by-products: nutritional and functional properties. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 80, 51–60 (2018).

Yahia, E. M. & Woolf, A. B. Avocado (Persea Americana Mill.). In Postharvest Biology and Technology of Tropical and Subtropical Fruits (125–186e). Woodhead Publishing. (2011).

Duarte, P. F., Chaves, M. A., Borges, C. D. & Mendonça, C. R. B. Avocado: characteristics, health benefits and uses. Ciência rural, 46, pp.747–754. (2016).

Ayala Silva, T. & Ledesma, N. Avocado history, biodiversity and production. Sustainable horticultural systems: Issues, technology and innovation, pp.157–205. (2014).

Salazar-López, N. J. et al. Avocado fruit and by-products as potential sources of bioactive compounds. Food Research International, 138, p.109774. (2020).

Qi, Y., Wei, D., Shi, G. M., Zhang, M. & Qi, Y. Amorphous/nanocrystalline carbonized hydrochars with isomeric heterogeneous interfacial polarizations for high-performance microwave absorption. Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 12429 (2019).

Zeng, G., Han, J., Dai, B., Liu, X., Li, J., Chen, C., … Sun, D. (2017). Preparation and characterization of alkaline anion exchange membrane for fuel cells application.Journal of Nanotechnology, 2017.

Naeem, S. et al. Sorption properties of iron impregnated activated carbon web for removal of methylene blue from aqueous media. Fibers Polym. 17, 1245–1255 (2016).

Nizamuddin, S. et al. Upgradation of chemical, fuel, thermal, and structural properties of rice husk through microwave-assisted hydrothermal carbonization. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 25, 17529–17539 (2018).

Costa, M. E. G., da Costa Assunção, F. P., Teribele, T., Pereira, L. M., de Castro,D. A. R., Santo, M. C., … Machado, N. T. (2021). Characterization of Bio-Adsorbents Produced by Hydrothermal Carbonization of Corn Stover: Application on the Adsorption of Acetic Acid from Aqueous Solutions. Energies, 14(23), 8154.

Spagnuolo, D., Iannazzo, D., Len, T., Balu, A. M., Morabito, M., Genovese, G., … Bressi,V. (2023). Hydrochar from Sargassum muticum: a sustainable approach for high-capacity removal of Rhodamine B dye. RSC Sustainability, 1(6), 1404–1415.

Rajasekaran, S. J. & Raghavan, V. Facile synthesis of activated carbon derived from Eucalyptus globulus seed as efficient electrode material for supercapacitors. Diam. Relat. Mater. 109, 108038 (2020).

Mahamad, M. N., Zaini, M. A. A. & Zakaria, Z. A. Preparation and characterization of activated carbon from pineapple waste biomass for dye removal. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 102, 274–280 (2015).

Liu, X. Y., Huang, M., Ma, H. L., Zhang, Z. Q., Gao, J. M., Zhu, Y. L., … Guo, X.Y. (2010). Preparation of a carbon-based solid acid catalyst by sulfonating activated carbon in a chemical reduction process. Molecules, 15(10), 7188–7196.

Zhu, G., Xing, X., Wang, J. & Zhang, X. Effect of acid and hydrothermal treatments on the dye adsorption properties of biomass-derived activated carbon. J. Mater. Sci. 52, 7664–7676 (2017).

Hashem, M., Hassan, H. S. M., Kamel, S. H., Amr, A. & AbdelBary, E. M. A.E.G.E. and Cost-Effective Potentiometric Platforms Modified with Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) and Based on Imprinted Receptors for Fluvoxamine Assessment. Polymers, 12(3), p.673. (2020).

Duman, G. Preparation of novel porous carbon from hydrothermal pretreated textile wastes: effects of textile type and activation agent on structural and adsorptive properties. J. Water Process. Eng. 43, 102286 (2021).

Wei, J. et al. Adsorption and co-adsorption of tetracycline and doxycycline by one-step synthesized iron loaded sludge biochar. Chemosphere, 236, p.124254. (2019).

Ahmad, S., Zhu, X., Wei, X. & Zhang, S. Influence of process parameters on hydrothermal modification of soybean residue: Insight into the nutrient, solid biofuel, and thermal properties of hydrochars. Journal of Environmental Management, 283, p.111981 (2021).

Miliotti, E. et al. Characterization of chemically and physically activated carbons from lignocellulosic ethanol lignin-rich stream via hydrothermal carbonization and slow pyrolysis pretreatment. Energies 13 (16), 4101 (2020).

Guo, Z., Zhang, X., Kang, Y. & Zhang, J. Biomass-derived carbon sorbents for cd (II) removal: activation and adsorption mechanism. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 5 (5), 4103–4109 (2017).

Bai, R. S. & Abraham, T. E. Studies on enhancement of cr (VI) biosorption by chemically modified biomass of rhizopus nigricans. Water Res. 36 (5), 1224–1236 (2002).

Aravind, M. & Amalanathan, M. Structural, morphological, and optical properties of country egg shell derived activated carbon for dye removal. Mater. Today: Proc. 43, 1491–1495 (2021).

Said, A., Tekasakul, S. & Phoungthong, K. Investigation of hydrochar derived from male oil palm flower: characteristics and application for dye removal. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 29 (1), 807–816 (2020).

Tran, T. H. et al. Adsorption isotherms and kinetic modeling of methylene blue dye onto a carbonaceous hydrochar adsorbent derived from coffee husk waste. Sci. Total Environ. 725, 138325 (2020).

El Ouadrhiri, F., Saleh, E. A. M., Husain, K., Adachi, A., Hmamou, A., Hassan, I.,… Lahkimi, A. (2023). Acid assisted-hydrothermal carbonization of solid waste from essential oils industry: Optimization using I-optimal experimental design and removal dye application. Arabian Journal of Chemistry, 16(8), 104872.

Yihunu, E. W., Minale, M., Abebe, S. & Limin, M. Preparation, characterization and cost analysis of activated Biochar and hydrochar derived from agricultural waste: a comparative study. SN Appl. Sci. 1, 1–8 (2019).

Yurdakal, S., Garlisi, C., Özcan, L., Bellardita, M. & Palmisano, G. (Photo) catalyst characterization techniques: adsorption isotherms and BET, SEM, FTIR, UV–Vis, photoluminescence, and electrochemical characterizations. In Heterogeneous photocatalysis (pp. 87–152). Elsevier. (2019).

Yang, F., Zhang, J., Lin, T., Ke, L., Huang, L., Deng, S. P., … Lu, M. (2023). Fabrication of waste paper/graphene oxide three-dimensional aerogel with dual adsorption capacity toward methylene blue and ciprofloxacin. Journal of the Iranian Chemical Society, 20(4), 801–816.

Wilk, M., Śliz, M. & Gajek, M. The effects of hydrothermal carbonization operating parameters on high-value hydrochar derived from beet pulp. Renew. Energy. 177, 216–228 (2021).

de Souza, T. N. V., de Carvalho, S. M. L., Vieira, M. G. A., da Silva, M. G. C., Brasil, D. D. & S. B Adsorption of basic dyes onto activated carbon: experimental and theoretical investigation of chemical reactivity of basic dyes using DFT-based descriptors. Appl. Surf. Sci. 448, 662–670 (2018).

Sirajudheen, P., Karthikeyan, P., Ramkumar, K. & Meenakshi, S. Effective removal of organic pollutants by adsorption onto Chitosan supported graphene oxide-hydroxyapatite composite: A novel reusable adsorbent. J. Mol. Liq. 318, 114200 (2020).

Costa, M. E. G., da Costa Assunção, F. P., Teribele, T., Pereira, L. M., de Castro,D. A. R., Santo, M. C., … Machado, N. T. (2021). Characterization of Bio-Adsorbents Produced by Hydrothermal Carbonization of Corn Stover: Application on the Adsorption of Acetic Acid from Aqueous Solutions. Energies 2021, 14, 8154.

Asim, N., Amin, M. H., Alghoul, M. A., Sulaiman, S. N. A., Razali, H., Akhtaruzzaman,M., … Sopian, K. (2021). Developing of chemically treated waste biomass adsorbent for dye removal. Journal of Natural fibers, 18(7), 968–977.

Arivoli, S., Hema, M., Martin, P. & Prasath, D. Adsorption of malachite green onto carbon prepared from borassus bark. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. Sect. A. 34 (2), 31–42 (2009).

Tharayil, J. M. & Chinnaiyan, P. Sustainable waste valorization: novel Areca catechu L. husk Biochar for anthraquinone dye adsorption-Characterization, modelling, kinetics, and isotherm studies. Results Eng. 20, 101624 (2023).

Aravindhan, S., Kumar, G. B., Saravanan, M. & Arumugam, A. Delonix regia biomass as an eco-friendly biosorbent for effective Alizarin red S textile dye removal: characterization, kinetics, and isotherm studies. Bioresource Technol. Rep., 101721. (2023).

Lata, H., Mor, S., Garg, V. K. & Gupta, R. K. Removal of a dye from simulated wastewater by adsorption using treated parthenium biomass. J. Hazard. Mater. 153 (1–2), 213–220 (2008).

Dawood, S. & Sen, T. K. Removal of anionic dye congo red from aqueous solution by Raw pine and acid-treated pine cone powder as adsorbent: equilibrium, thermodynamic, kinetics, mechanism and process design. Water Res. 46 (6), 1933–1946 (2012).

Dogar, S. et al. Utilization of biomass fly Ash for improving quality of organic dye-contaminated water. ACS Omega. 5 (26), 15850–15864 (2020).

Nazir, R., Khan, M., Rehman, R. U., Shujah, S., Khan, M., Ullah, M., … Ahmad, I. (2020).Adsorption of selected azo dyes from an aqueous solution by activated carbon derived from Monotheca buxifolia waste seeds. Soil Water Res, 15(3), 166–172.

Zhang, Z. et al. Efficient removal of methylene blue using the mesoporous activated carbon obtained from mangosteen peel wastes: Kinetic, equilibrium, and thermodynamic studies. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, 315, p.110904. (2021).

Nodehi, R., Shayesteh, H. & Rahbar-Kelishami, A. Fe3O4@ NiO core–shell magnetic nanoparticle for highly efficient removal of Alizarin red S anionic dye. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 19 (4), 2899–2912 (2022).

Yagub, M. T., Sen, T. K., Afroze, S. & Ang, H. M. Dye and its removal from aqueous solution by adsorption: a review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 209, 172–184 (2014).

Munagapati, V. S., Wen, H. Y., Vijaya, Y., Wen, J. C., Wen, J. H., Tian, Z., … Raul Garcia, J. (2021). Removal of anionic (Acid Yellow 17 and Amaranth) dyes using aminated avocado (Persea americana) seed powder: adsorption/desorption, kinetics, isotherms,thermodynamics, and recycling studies. International Journal of Phytoremediation, 23(9), 911–923.

Langmuir, I. The adsorption of gases on plane surfaces of glass, mica and platinum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 40 (9), 1361–1403 (1918).

Freundlich, H. M. F. Over the adsorption in solution. J. Phys. Chem. 57 (385471), 1100–1107 (1906).

Temkin, M. J. & Pyzhev, V. Recent Modifications To Langmuir Isotherms’, Acta Physicochimpp. 217–222 (URSS, 1940).

Redlich, O. & Peterson, D. L. A useful adsorption isotherm. J. Phys. Chem. 63 (6), 1024–1024 (1959).

Malarvizhi, R. & Ho, Y. S. The influence of pH and the structure of the dye molecules on adsorption isotherm modeling using activated carbon. Desalination 264 (1–2), 97–101 (2010).

Kumar, K. V. & Sivanesan, S. Isotherm parameters for basic dyes onto activated carbon: comparison of linear and non-linear method. J. Hazard. Mater. 129 (1–3), 147–150 (2006).

Aravindhan, S., Kumar, G. B., Saravanan, M. & Arumugam, A. Delonix regia biomass as an eco-friendly biosorbent for effective Alizarin Red S textile dye removal: Characterization, kinetics, and isotherm studies. Bioresource Technology Reports, 25, p.101721. (2024).

Bhomick, P. C. et al. Alizarin red S adsorption onto biomass-based activated carbon: optimization of adsorption process parameters using Taguchi experimental design. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 17 (2), 1137–1148 (2020).

Venkatesh, S. & Arutchelvan, V. Biosorption of Alizarin red dye onto immobilized biomass of Canna Indica: isotherm, kinetics, and thermodynamic studies. Desalination Water Treat. 196, 409–421 (2020).

Gautam, R. K., Gautam, P. K., Chattopadhyaya, M. C. & Pandey, J. D. Adsorption of Alizarin Red S onto biosorbent of Lantana camara: kinetic, equilibrium modeling and thermodynamic studies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, India Section A: Physical Sciences, 84, pp.495–504. (2014).

Nasoudari, E., Ameri, M., Shams, M., Ghavami, V. & Bonyadi, Z. The biosorption of Alizarin red S by Spirulina Platensis; process modelling, optimisation, kinetic and isotherm studies. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 103 (3), 633–647 (2023).

Özdemir, M., Durmuş, Ö., Şahin, Ö. & Saka, C. Removal of Methylene Blue, Methyl Violet, Rhodamine B, Alizarin red, and bromocresol green dyes from aqueous solutions on activated cotton stalks. Desalination Water Treat. 57 (38), 18038–18048 (2016).

Wanassi, B. et al. Carbonaceous adsorbents derived from textile cotton waste for the removal of Alizarin S dye from aqueous effluent: kinetic and equilibrium studies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 24, 10041–10055 (2017).

Bhomick, P. C., Supong, A., Baruah, M., Pongener, C. & Sinha, D. Pine cone biomass as an efficient precursor for the synthesis of activated biocarbon for adsorption of anionic dye from aqueous solution: isotherm, kinetic, thermodynamic and regeneration studies. Sustainable Chem. Pharm. 10, 41–49 (2018).

Albadarin, A. B. & Mangwandi, C. Mechanisms of Alizarin red S and methylene blue biosorption onto Olive stone by-product: isotherm study in single and binary systems. J. Environ. Manage. 164, 86–93 (2015).

Lagergren About the theory of so-called adsorption of soluble substances, KungligaSvenskaVetenskHandl., vol. 24, pp. 1 – 39, 1898.

Ho, Y. S. & MaKay, G. Pseudo-second order model for sorption processes. Process Biochem. 34 (5), 451–465 (1999).

Hu, Q., Pang, S. & Wang, D. ‘In-depth Insights into Mathematical Characteristics, Selection Criteria and Common Mistakes of Adsorption Kinetic Models: A Critical Review’, Separation & Purification Reviews, vol. 51, no. 3, pp. 281–299 (2022).

Weber, W. J. & Morris, J. C. Kinetics of adsorption on carbon from solution. J. Sanit. Eng. Div. 89 (2), 31–59 (1963).

Boyd, G. E., Adamson, A. W. & Myers, L. S. The exchange adsorption of ions from aqueous solutions by organic zeolites, II. Kinetics 1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 69 (11), 2836–2848 (1947).

Chieng, H. I., Lim, L. B. & Priyantha, N. Enhancing adsorption capacity of toxic malachite green dye through chemically modified breadnut Peel: equilibrium, thermodynamics, kinetics and regeneration studies. Environ. Technol. 36 (1), 86–97 (2015).

Bharath Balji, G. & Senthil Kumar, P. Adsorptive removal of alizarin red S onto sulfuric acid-modified avocado seeds: kinetics, equilibrium, and thermodynamic studies. Adsorption Science & Technology, 2022, 3137870. (2022).

Funding

This study does not receive any financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors Contributions: G. Bharath Balji: Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology; Validation; Writing original-draftP. Senthil Kumar: Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology; Validation; SupervisionV. Parthasarathy, B. Chitra, Gayathri Rangasamy: Conceptualization; Visualization; Formal Analysis; Data curation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

All authors were participated in this work.

Consent to publish

All authors agree to publish.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Balji, G.B., Kumar, P.S., Chitra, B. et al. Adsorptive potential of hydrochar produced from avocado waste biomass for the sequestration of Alizarin red S dye from aquatic environment. Sci Rep 15, 33820 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01273-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01273-y