Abstract

In this paper, we present an orthogonal ghost imaging (OGI) method based on two-dimensional discrete cosine transform (2D-DCT) patterns. Unlike traditional methods that are based on random or sinusoidal patterns, our method relies on structured orthogonal patterns to enhance both image quality and reconstruction speed, outperforming random and sinusoidal-based approaches in terms of reconstruction fidelity and computational efficiency. A new reconstruction formula is derived in our approach. In addition, using a phase-shift illumination pattern technique helps to effectively reduce environmental noise. Simulation and experimental results show that high-quality image reconstruction is achievable even with reduced sampling rates. For instance, using only 30% of the measurements is enough to meet the Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) threshold predicted by Shannon entropy. Compared to differential and sinusoidal ghost imaging techniques, the proposed method consistently outperforms them in terms of signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and reconstruction efficiency. These findings suggest that OGI offers a promising direction for efficient and low-cost ghost imaging systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ghost imaging (GI), known as coincidence imaging, two-photon imaging, or correlated-photon imaging, is an unconventional imaging technique in which the image of an object is reconstructed based on the intensity correlation between two light beams. The beam that interacts with the object is referred to as the signal beam, while the other beam, which does not interact with the object but reaches the detector, is called the reference beam.

Pittman et al. were the first to demonstrate GI in 1995, using quantum-entangled photons1. For several years, GI was believed to be feasible only with quantum sources. However, later studies showed that similar correlations could also be achieved using classical light sources - indicating that ghost imaging is not exclusive to quantum mechanics but can be explained through classical physics as well. In particular, Bennink et al. were among the first who reconstructed GI with classical light in 2002, which validated the classical interpretation2,3,4,5,6.

The concept of Computational Ghost Imaging (CGI) was first proposed by Shapiro7, introducing a new method that eliminates the need for a reference beam by using patterns calculated offline. This innovation simplified the optical setup and made the practical implementation of ghost imaging more feasible. In 2009, Bromberg et al. demonstrated CGI experimentally using a single-pixel detector8. Over time, ghost imaging has evolved into an effective platform for developing novel imaging technologies and cost-effective imaging systems. Its applications span a wide range, including imaging through turbulence9,10,11,12, lensless imaging13,14, x-ray imaging15,16,17, 3D imaging with single-pixel detectors18,19, compressive radar20, terahertz single pixel imaging21,22. These advances highlight the growing importance of CGI in real-world applications.

In response to the limitations of traditional computational ghost imaging (CGI) methods, this study explores a novel approach called Orthogonal Ghost Imaging (OGI), which employs two-dimensional Discrete Cosine Transform (2D-DCT) patterns. Unlike random or sinusoidal illuminations, the use of orthogonal DCT basis functions allows for more efficient sampling and sharper reconstructions. A new image reconstruction formula is derived based on the inner product properties of these orthogonal patterns. Furthermore, to reduce environmental noise, a phase-shift modulation technique is incorporated. The efficacy of the proposed method is validated through both simulation and experimental results, showing significant improvements in image quality and reconstruction performance.

Over the years, researchers have developed various reconstruction methods to overcome the limitations of traditional CGI. For example, correlation of intensity powers23, Differential Ghost Imaging (DGI)24, Normalized GI25, and Pseudo-inverse GI26 were among the first efforts to improve the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of the reconstructed images. More recently, Singular Value Decomposition (SVD)-based techniques27,28,29 have been applied to extract meaningful components from measurement data more effectively. In parallel, compressive sensing methods have gained attention for their ability to reconstruct images from significantly fewer measurements by exploiting signal sparsity30,31,32,33. These methods rely on the assumption that most natural images are sparse in some transform domain. Another effective method has involved the use of structured and orthogonal illumination patterns. For example, sinusoidal ghost imaging (SGI)34and orthogonal basis approaches35,36,37,38 aim to improve overlap between the patterns and the target object’s spatial features, which enhances reconstruction performance. These studies demonstrate that exploiting spatial frequency characteristics of natural images can significantly enhance image quality and efficiency.

More recent research has explored diverse approaches to further enhance the efficiency and versatility of ghost imaging. For example, hybrid transform-based methods that integrate DCT, Hadamard, and Haar matrices have demonstrated improved image reconstruction performance with fewer measurements39. Other approaches focus on data augmentation to enhance the quality of ghost imaging40, or leverage compressive sensing in plenoptic imaging setups to recover spatial and angular information simultaneously41. These recent findings show how ghost imaging continues to evolve toward more flexible and efficient designs, supporting the value of simple, low-shot reconstruction approaches like the one presented here. Our method builds upon these ideas by proposing an orthogonal pattern-based framework with improved computational efficiency and noise robustness.

Model and principle

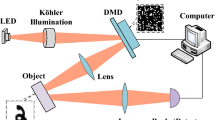

The schematic experimental setup of CGI is shown in Fig. 1. The target object is illuminated by a projector with random intensity patterns \(\{I_{r}(x,y)\}\), and a bucket detector measures the corresponding transmitted intensity\(\{B_{r}\}\). The image of the target scene is usually reconstructed through Bromberg Equation as8:

where \(\langle \cdot \rangle = \frac{1}{N} \sum _{r=1}^{N} \cdot\) denotes an ensemble average over N phase realizations. A higher value of B means more overlap of random intensity patterns with the target, and these patterns have the greatest effect on image reconstruction. Another algorithm that increases the quality of ghost imaging is differential ghost imaging (DGI)24:

where \(I_r\) is the sum of all pixels of the illumination pattern. Random patterns are used for both reconstruction methods mentioned above. In this research, orthogonal functions of DCT as illumination patterns are used instead of random intensity patterns, one formulate as:

where x, y are the 2D cartesian coordinates, \(\{u = 0, 1, ..., m_{1}-1\}\) and \(\{v = 0, 1, ..., m_{2}-1\}\) are the horizontal and vertical spatial frequencies, respectively, and \(\{m_{1}\times m_{2}\}\) is pixel resolution of image. The following matrix is obtained for each u, v by sweeping x, y from 0 to \({m_{1}-1}\) and 0 to \({m_{2}-1}\), respectively:

In image processing42, the above matrices are called the mapping matrices from the cartesian space to the DCT space, which are known as the basis of DCT space. The image is described using these basis as follows:

where \(T_{uv}\) represents the weighting coefficients of each of the basis of the DCT space in image reconstruction. Each of the matrices illuminates the object as illuminating patterns, and the Bucket detector records the intensity of the reflected pattern. According to the property of orthogonal basis, we define \(<S_{uv},S_{u^{\prime } v^{\prime }}>=||S_{uv}||^2 \delta _{uu^{\prime }}\delta _{vv^{\prime }}\) where \(\delta\) is Kronecker delta. Therefor, \(T_{uv}={<S_{uv},F>}\). Where \({<S_{uv},F>}\) is the value measured by the bucket detector in GI setup. The formula of ghost imaging reconstruction is as follows:

where \(B_{uv}\) is intensity of signal measured by detector.

The presence of negative intensity is necessary to prevent intensity saturation during image reconstruction. However, a challenge is the way the Bucket detector works so that the detector is not able to distinguish between the environmental noise and the signals received from the object. To solve this problem, the phase-shift method can be used, which leads to the elimination of noises that are statistically identical35,36,37,38. This phenomenon is especially evident when the sampling rate significantly differs from the flashing rate of environmental light sources, resulting in substantial noise reduction from environmental illumination. For this purpose each weighting factor of these patterns requires two measurements with patterns that have a phase difference of \(\pi\). Therefore, we use the following two groups of patterns:

Figures 2(a)-(b) show part of two sets of 2D-DCT \((m_{1}=m_{2}=64)\) patterns generated from Eq. (7), respectively. The cycle frequency increases by 1/2 with each step from left to right or from top to bottom. As it is clear from the Fig. 2, the frequency patterns will become more intense with each step moving to the right and down of Figs. 2(a)-(b).

Part of the two sets of illumination patterns for \(m_{1}=m_{2}=8\) used in this paper. (a) Patterns generated by S(x, y; u, v) in Eq. (7), (b) Phase-shifted counterparts generated by \(S^{\prime }(x,y;u,v)\) in Eq. (7). These two groups form the basis of the differential acquisition strategy used to eliminate background noise.

The detector can collect each type of light, whether direct or indirect, or a combination of both for imaging. Thus, the total response of the detector received for each series of orthogonal basis can be expressed as follows:

where T(x, y) is the transmission function of an object and \(b_{DC}\) is the environmental background light. The following differential equation can annihilate the \(b_{DC}\) term and obtain the spectrum of DCT coefficients without background noise:

Figure 3(a) shows the order of displaying patterns on the object. By changing this order, as shown in Fig. 3(b), and adopting a zig-zag scanning strategy that prioritizes low-frequency DCT components, the image can be reconstructed with fewer measurements-demonstrating that the projection order significantly influences reconstruction efficiency.

Another challenge is using cosine functions, because projector can not display negative values. To solve this issue, we normalize the bucket data to the range of (0,1). Accordingly, the intensity corresponding to a black pattern illumination is set to 0, and for a white pattern illumination, it is set to 1. Subsequently, applying \(B_{uv}=2 B_{uv}-1\) leads to the generation of the corresponding negative intensities. The subtraction in Eq. (9) implements a differential phase-shift strategy designed to remove static environmental interference and system offsets.

Our method differs from previous orthogonal ghost imaging approaches in several important ways.These differences are mainly visible in the convergence speed, robustness to noise and implementation complexity. For instance, the technique described in35 uses a block-style ordering of DCT patterns. In contrast, we apply a zig-zag scan that starts with low-frequency components. This choice helps capture the image’s overall structure early on, which speeds up convergence and tends to yield better reconstructions, especially when measurements are limited.

In36, the authors use sinusoidal illumination patterns based on Fourier components, which are inherently complex-valued and require four separate projections per component to recover both real and imaginary parts. Our approach, by contrast, uses real-valued symmetric DCT patterns, needing only two complementary measurements. This significantly simplifies the setup and improves acquisition efficiency. Also, the method in38 performs DCT projections along each axis separately - first horizontal, then vertical - which effectively splits the image into two one-dimensional components. This method lacks full 2D coverage, which can lead to slower convergence and reduced accuracy in preserving important spatial details such as edges and textures. In contrast, we use full 2D-DCT patterns that better match the structure of natural images. This allows for faster convergence and improved image detail preservation43,44,45,46,47.

Experimental setup

A digital light projector (Casio XJ-A146) was used to illuminate the scene using two groups of 2D-DCT patterns with spatial frequencies (u, v). These patterns, with varying spatial frequencies, were generated at a resolution of \(64 \times 64\) pixels and 256 grayscale levels using a computer. The projector was placed at a fixed distance of 72 cm from the target and illuminated a \(2 \times 2~cm^2\) area of the scene for 0.15 seconds per pattern.

The transmitted light corresponding to each pattern was simultaneously measured by a Thorlabs DCC1545M camera, which acted as a bucket detector. To fully reconstruct a \(64 \times 64\) pixel image, a total of 8192 measurements were acquired. The complete acquisition process took approximately 68 minutes. Using this setup, we carried out both simulations and experiments to evaluate how well the proposed method performs in practice. The results are presented and discussed in the following section.

Discussion and results

We initiate our evaluation process with numerical simulation to compare the image quality produced by the novel approach with the other existing methods. Here, the target object for simulation is an image of \(200\times 200\) pixels with a square aperture of \(100\times 100\) pixels shown in Fig. 4a(I). DCT matrices are generated by the computer, and after interrogating the object matrix, the set of new matrix elements is reported as the intensity of the detector. The reconstructed image using Eq. (6) for 2000 shots can be seen in Fig. 4b(I). To quantitatively compare image quality, the parameter of \(SNR=\bar{s}^2/\sigma _n\) is used34,42, where \(\bar{s}\) is the average of the signal intensity, and \(\sigma _n\) is the variance of the background intensity.

Numerical simulation of a \(200\times 200\)-pixel image containing a square aperture of size \(100\times 100\). (a) Target image; (b) Reconstructed image using DCT-based illumination and Eq. (6) with 2000 shots. Subfigures ((I) and (II) show the reconstructed image and the intensity distribution along its central horizontal line, respectively, highlighting the spatial fidelity of the reconstruction.

In this paper, the difference in average intensity between the bright and dark areas of images conceptualizes as the signal, while the variations in the dark background conceptualizes as the noise. We compare the SNR result of the reconstructed image in Fig. 4 with the SNR values obtained from two methods of the DGI24 and the SGI34, presenting the results in Table 1.

In the SGI approach, the illuminant matrices are generated by the sinusoidal patterns34, and the image is reconstructed by \(G_{SGI}=\sum _{i=1}^{N}{B_{i}I_i(x,y)}\), which N is number of shots, \(I_i(x,y)\) is the sinusoidal patterns and \(B_{i}\) is the intensity corresponding to each pattern that is recorded by the detector after interacting with the object. As indicated in Table 1, the SNR value of the DGI method is 10.89 dB for \(10^5\) number of shots. While in the SGI method, despite a remarkable reduction in the number of shots, we have a significant improvement in the quality of the reconstructed image, and SNR is \(33.28\) \(dB\). As Table 1 shows, the SGI method improves image quality compared to DGI, achieving a higher SNR despite using fewer measurements. However, our proposed OGI method outperforms both, delivering the highest SNR (36.95 dB) while requiring even fewer shots than SGI. This demonstrates that modifications to the reconstruction equation can remarkably improve the quality of the reconstructed image.

Increasing the number of shots leads to sharper edges with higher visibility. But the question is, “How many shots are satisfactory as a lower bound to reconstruct an image?” The answer to this question depends on two factors. The first is related to the illuminant matrices, which according to the results of Table 1, DCT matrices are more satisfactory in the number of fewer shots, and the second is related to the level of image sparse. A sparse image is one in which most of the pixels are zero or close to zero, and the more sparse the image is, the fewer shots are needed for reconstruction43,44.

To study the image sparse effect, we choose a group of images (\(200\times 200\) ) pixels with different square aperture dimensions (non-zero image components) (\(40\times 40\)), (\(60\times 60\)), (\(80\times 80\)), (\(100\times 100\)) pixels which can be seen in Fig. 5a(I-IV) respectively.

We estimate the imaging quality by representing the peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR), which can be described by42:

where \(U_{0}\) is the target image matrix (\(m_{1}\times m_{2}\)) pixels, and U is the corresponding reconstructed image. The PSNR for the different apertures at corresponding sampling ratios (\(\beta\)) of 1, 2, 5, 10 and \(20\%\) are shown in Table (2). The sparsity of the image evidently has a strong influence on reconstruction quality. As the non-zero region of the image increases-from \(40\times 40\) to \(100\times 100\)-the PSNR values consistently decrease under a fixed sampling rate. This behavior aligns well with the principles of compressive sensing, which state that sparser images require fewer measurements to achieve reliable reconstruction. In accordance with Shannon’s entropy, for an image with n pixels that only k pixels have non-zero, if \(k\ll n\), the minimum number of measurements required for successful reconstruction is approximately given by47:

This expression is derived from the binary Shannon entropy and is commonly used in compressive sensing theory to estimate the minimum number of measurements required for accurate recovery of sparse signals. It assumes that the support of the sparse signal follows a Bernoulli distribution, where each component is non-zero with a fixed probability. Although real-world images often exhibit structured (rather than random) sparsity, the Bernoulli model is widely adopted in theoretical analysis as it provides a general information-theoretic lower bound. This approach helps characterize the fundamental limits of compressive acquisition independently of specific image content44,45,46.

(a) (I)-(IV) Target binary images with square apertures of sizes (\(40\times 40\)), (\(60\times 60\)), (\(80\times 80\)), (\(100\times 100\)), respectively. (b) (I)-(IV) Reconstructed results using the proposed OGI method with 5150 measurements. The comparison illustrates how increasing sparsity (i.e., smaller apertures) leads to better reconstruction performance under fixed measurement conditions.

In our simulation, the full image contains \(200 \times 200\) pixels , but only a \(40 \times 40\) central region contains non-zero values-meaning just 1600 pixels carry information and the rest remain zero. This makes the image highly sparse, with \(k=1600\) out \(n=40000\). Under this condition (\(k\ll n\)), using 5150 measurements meets the lower bound predicted by Shannon’s entropy, as described in Eq. (11). Figure 5b (I-IV). shows the reconstructed images for four different aperture sizes, all obtained using the same number of measurements (5150 shots). While the overall structure is visually preserved across all cases, the sparsest one \(40 \times 40\) achieves a PSNR above 30 dB. This results suggests that the method remains reliable even with limited sampling, and performs remarkably close to the theoretical lower bound predicted by Shannon entropy.

Reconstructed grayscale images of four standard test images (“house”, “boat”, “lake”, and “livingroom”) using the proposed OGI method at sampling rates of \(10\%\), \(30\%\), \(50\%\), and \(60\%\). The results show that visual quality improves with higher sampling, but becomes nearly saturated at around \(30\%\), confirming the method’s efficiency under compressed conditions.

To further evaluate the robustness of the proposed method on more realistic content, standard grayscale test images commonly used in image processing-namely, “house”, “boat”, “lake”, and “livingroom”-were also included in the simulations. Figure 6 (a-d) shows how the proposed method performs on these images at different sampling rates. As expected, the most noticeable jump in reconstruction quality happens around \(30\%\). Adding more measurements beyond that point yields only minimal visual enhancement, confirming a point of diminishing returns. This isn’t just something we observed; it’s supported by theory. As discussed in45,47, natural images tend to have a sparse representation in the DCT domain, where a small number of low-frequency components capture most of the structural information. That’s exactly what the DCT basis is good at-it captures essential features efficiently.

This alignment between the structure of natural images and the design of our method likely explains why the system performs so well even with relatively low sampling rates. In our method, the \(30\%\) sampling rate yields a PSNR above 30 dB, which confirms that the method remains robust and effective under sub-Nyquist conditions, and operates near the theoretical efficiency limit predicted by information theory. This can be explained by the fact that most of the coefficients in DCT-based representations are either zero or close to zero, while approximately one-third carry most of the meaningful information. These larger coefficients, due to strong alignment with image structures, play a key role in reconstructing the fine details with fewer measurements. To experimentally validate the performance of our proposed method, we implemented the setup shown in Fig. 1 collected experimental measurements. The results are shown in Figure 7a(I-V), which shows the reconstructed images at different sampling rates. The experimental reconstructions clearly improve as the sampling rate increases, particularly in terms of edge sharpness and structural clarity. The \(30\%\) sampling level appears to mark a practical threshold in the experimental setup-preserving essential image structure and fine edges without requiring significantly more measurements.

(a) Experimental reconstruction results using the proposed OGI method at sampling rates of 2, 10, 20, 30 and \(40\%\). (b) Corresponding 3D intensity surface plots for each case, where x and y represent spatial pixel positions and z indicates intensity. The increasing sharpness and edge definition in the surfaces highlight how the method preserves structural detail even under limited measurements.

To get a more intuitive sense of how measurement count influences reconstruction-especially near object boundaries-we also generated 3D intensity surface plots from the same experimental data, shown in Figure 7b(I-V). These visualizations help emphasize subtle differences that aren’t always easy to spot in the grayscale images alone. In the 3D plots, the surfaces become noticeably sharper and more defined as the sampling rate increases. The steepness and clarity of the edges, in particular, improve significantly, making it easier to assess the system’s ability to recover fine spatial details. This form of visualization not only complements the 2D results visually, but also gave us deeper insight into how edge contrast evolves across different sampling conditions. These experimental findings remain consistent with the entropy-based expectations introduced earlier, reinforcing the theoretical foundation observed in the PSNR analysis. Even with a limited number of measurements, the reconstructed images maintain both visual clarity and structural detail-suggesting that the method operates close to the information-theoretic limit described by Shannon.

Up to this point, we’ve looked at the quality of the reconstructed images-but understanding how much computational effort each method requires is just as important. An algorithm isn’t truly efficient if it only works well on specific hardware. For this reason, we also assess computational complexity, quantified by the number of additions and multiplications, to provide a clearer, hardware-independent view of how computationally efficient each method really is42. To better understand how the two methods compare in terms of computational cost, we examined the number of arithmetic operations required to implement GIT (Eq. (1)) and OGI (Eq. (6)), where N is the number of measurements and \(m^2\) is the image resolution. The results of this comparison are summarized in Table 3.

We observed that the computational advantage becomes more apparent as the number of measurements increases. Specifically, the complexity ratio is given by \(C(N)={(3Nm^2+4m^2+N+1)}/{(2Nm^2)}\) ,which simplifies to approximately 1.5. In other words, when sampling is high, OGI cuts the number of operations by about one third compared to GIT. This reduction translates into a noticeably more efficient reconstruction process. Table 4. illustrates this trend in practice for a \(64\times 64\) image at various measurement levels. The data confirms what we expected: the computational load of OGI stays consistently lower, while reconstruction quality remains high. All in all, the results show that OGI doesn’t just perform better-it does so without relying on special hardware, and even with fewer measurements.

Conclusion

In this paper, we proposed an orthogonal ghost imaging (OGI) framework based on two-dimensional discrete cosine transform (2D-DCT) patterns, integrated with a two-phase shift acquisition strategy to effectively address the issue of negative intensity values. This method benefits from the inherent energy compaction and sparsity properties of the DCT basis, which allow for efficient sampling and accurate image reconstruction with fewer measurements.

Through extensive simulations and physical experiments, we demonstrated that the proposed method consistently outperforms traditional ghost imaging techniques. It achieves peak signal-to-noise ratios (PSNR) exceeding 30 dB at sampling rates as low as \(30\%\), while also reducing computational complexity by approximately one-third compared to benchmark methods. These improvements highlight the method’s practicality, especially in scenarios where minimizing acquisition time and computational resources is critical.

The strong agreement between simulation and experimental results further validates the robustness of the proposed approach and its applicability in real-world imaging setups. Even under limited sampling conditions, the method maintains high visual fidelity and structural accuracy, operating near the theoretical efficiency bounds predicted by compressive sensing theory.

Looking ahead, the flexibility of the OGI framework makes it well-suited for further extensions, including color image reconstruction, real-time processing, and imaging under dynamic lighting or noisy environments. These directions open up promising pathways toward developing scalable, low-cost, and hardware-friendly ghost imaging systems for practical applications.

Data availability

The data sets used and/or analyzed during current study available for the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Pittman, T. B., Shih, Y. H., Strekalov, D. V. & Sergienko, A. V. Optical imaging by means of two-photon quantum entanglement. Phys. Rev. A 52, R3429–R3432 (1995) https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevA.52.R3429.

Bennink, R. S., Bentley, S. J. & Boyd, R. W. “two-photon’’ coincidence imaging with a classical source. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 113601 (2002) https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.113601.

Valencia, A., Scarcelli, G., D’Angelo, M. & Shih, Y. Two-photon imaging with thermal light. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 063601 (2005) https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.063601.

Chen, X.-H., Liu, Q., Luo, K.-H. & Wu, L.-A. Lensless ghost imaging with true thermal light. Opt. Lett. 34, 695–697 (2009) https://opg.optica.org/ol/abstract.cfm?URI=ol-34-5-695.

Wang, K. & Cao, D.-Z. Subwavelength coincidence interference with classical thermal light. Phys. Rev. A 70, 041801 (2004) https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevA.70.041801.

Ferri, F. et al. High-resolution ghost image and ghost diffraction experiments with thermal light. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 183602 (2005) https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.183602.

Shapiro, J. H. Computational ghost imaging. Phys. Rev. A 78, 061802 (2008) https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevA.78.061802.

Bromberg, Y., Katz, O. & Silberberg, Y. Ghost imaging with a single detector. Phys. Rev. A 79, 053840 (2009) https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevA.79.053840.

Dixon, P. B. et al. Quantum ghost imaging through turbulence. Phys. Rev. A 83, 051803 (2011) https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevA.83.051803.

Hardy, N. D. & Shapiro, J. H. Reflective ghost imaging through turbulence. Phys. Rev. A 84, 063824 (2011) https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevA.84.063824.

Gao, Z., Cheng, X., Zhang, L., Hu, Y. & Hao, Q. Compressive ghost imaging in scattering media guided by region of interest. Journal of Optics 22, 055704. https://doi.org/10.1088/2040-8986/ab8612 (2020).

Durán, V. et al. Compressive imaging in scattering media. Opt. Express 23, 14424–14433 (2015) https://opg.optica.org/oe/abstract.cfm?URI=oe-23-11-14424.

Liu, X.-F. et al. Lensless ghost imaging with sunlight. Opt. Lett. 39, 2314–2317 (2014) https://opg.optica.org/ol/abstract.cfm?URI=ol-39-8-2314.

Chen, X.-H., Liu, Q., Luo, K.-H. & Wu, L.-A. Lensless ghost imaging with true thermal light. Opt. Lett. 34, 695–697 (2009) https://opg.optica.org/ol/abstract.cfm?URI=ol-34-5-695.

Greenberg, J., Krishnamurthy, K. & Brady, D. Compressive single-pixel snapshot x-ray diffraction imaging. Opt. Lett. 39, 111–114 (2014) https://opg.optica.org/ol/abstract.cfm?URI=ol-39-1-111.

Yu, H. et al. Fourier-transform ghost imaging with hard x rays. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 113901 (2016) https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevLett.117.113901.

Zhang, A.-X., He, Y.-H., Wu, L.-A., Chen, L.-M. & Wang, B.-B. Tabletop x-ray ghost imaging with ultra-low radiation. Optica 5, 374–377 (2018) https://opg.optica.org/optica/abstract.cfm?URI=optica-5-4-374.

Sun, B. et al. 3d computational imaging with single-pixel detectors. Science 340, 844–847 (2013). https://www.science.org/doi/abs/10.1126/science.1234454. https://www.science.org/doi/pdf/10.1126/science.1234454.

Soltanlou, K. & Latifi, H. Three-dimensional imaging through scattering media using a single pixel detector. Appl. Opt. 58, 7716–7726 (2019) https://opg.optica.org/ao/abstract.cfm?URI=ao-58-28-7716.

Baraniuk, R. & Steeghs, P. Compressive radar imaging. In 2007 IEEE Radar Conference, 128–133 (2007).

Shrekenhamer, D., Watts, C. M. & Padilla, W. J. Terahertz single pixel imaging with an optically controlled dynamic spatial light modulator. Opt. Express 21, 12507–12518 (2013) https://opg.optica.org/oe/abstract.cfm?URI=oe-21-10-12507.

Hornett, S. M., Stantchev, R. I., Vardaki, M. Z., Beckerleg, C. & Hendry, E. Subwavelength terahertz imaging of graphene photoconductivity. Nano Letters 16, 7019–7024. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b03168 (2016).

Chan, K. W. C., O’Sullivan, M. N. & Boyd, R. W. Optimization of thermal ghost imaging: high-order correlations vs. background subtraction. Opt. Express 18, 5562–5573 (2010) https://opg.optica.org/oe/abstract.cfm?URI=oe-18-6-5562.

Ferri, F., Magatti, D., Lugiato, L. A. & Gatti, A. Differential ghost imaging. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 253603 (2010) https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.253603.

Sun, B., Welsh, S. S., Edgar, M. P., Shapiro, J. H. & Padgett, M. J. Normalized ghost imaging. Opt. Express 20, 16892–16901 (2012) https://opg.optica.org/oe/abstract.cfm?URI=oe-20-15-16892.

Zhang, C., Guo, S., Cao, J., Guan, J. & Gao, F. Object reconstitution using pseudo-inverse for ghost imaging. Opt. Express 22, 30063–30073 (2014) https://opg.optica.org/oe/abstract.cfm?URI=oe-22-24-30063.

Zhang, X. et al. Singular value decomposition ghost imaging. Opt. Express 26, 12948–12958 (2018) https://opg.optica.org/oe/abstract.cfm?URI=oe-26-10-12948.

Chen, L.-Y. et al. Color ghost imaging based on optimized random speckles and truncated singular value decomposition. Optics & Laser Technology 169, 110007 (2024) https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0030399223009003.

Ma, P., Meng, X., Liu, F., Yin, Y. & Yang, X. Singular value decomposition compressive ghost imaging based on multiple image prior information. Optics and Lasers in Engineering 182, 108471 (2024) https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0143816624004494.

Katz, O., Bromberg, Y. & Silberberg, Y. Compressive ghost imaging. Applied Physics Letters 95, 131110. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3238296 (2009) https://pubs.aip.org/aip/apl/article-pdf/doi/10.1063/1.3238296/16678114/131110_1_online.pdf.

Candes, E. J. & Wakin, M. B. An introduction to compressive sampling. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 25, 21–30 (2008).

Romberg, J. Imaging via compressive sampling. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 25, 14–20 (2008).

Duarte, M. F. et al. Single-pixel imaging via compressive sampling. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 25, 83–91 (2008).

Khamoushi, S. M. M., Nosrati, Y. & Tavassoli, S. H. Sinusoidal ghost imaging. Opt. Lett. 40, 3452–3455 (2015) https://opg.optica.org/ol/abstract.cfm?URI=ol-40-15-3452.

Liu, B.-L., Yang, Z.-H., Liu, X. & Wu, L.-A. Coloured computational imaging with single-pixel detectors based on a 2d discrete cosine transform. Journal of Modern Optics 64, 259–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500340.2016.1229507 (2017).

Zhang, Z., Ma, X. & Zhong, J. Single-pixel imaging by means of fourier spectrum acquisition. Nature communications 6, 6225. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7225 (2015).

Wang, L. & Zhao, S. Fast reconstructed and high-quality ghost imaging with fast walsh-hadamard transform. Photon. Res. 4, 240–244 (2016) https://opg.optica.org/prj/abstract.cfm?URI=prj-4-6-240.

Tanha, M., Ahmadi-Kandjani, S. & Kheradmand, R. Fast ghost imaging and ghost encryption based on the discrete cosine transform. Physica Scripta 2013, 014059. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-8949/2013/T157/014059 (2013).

Zhao, Y.-N. et al. Computational ghost imaging with hybrid transforms by integrating hadamard, discrete cosine, and haar matrices. Optics and Lasers in Engineering 181, 108408 (2024) https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0143816624003865.

Coakley, K. J. et al. Emission ghost imaging: Reconstruction with data augmentation. Phys. Rev. A 109, 023501 (2024) https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevA.109.023501.

Petrelli, I. et al. Compressive sensing-based correlation plenoptic imaging. Frontiers in Physics 11 (2023). https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/physics/articles/10.3389/fphy.2023.1287740.

Gonzales, R. C. & Wintz, P. Digital image processing 2nd edn. (Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc, USA, 1987).

Du, J., Gong, W. & Han, S. The influence of sparsity property of images on ghost imaging with thermal light. Opt. Lett. 37, 1067–1069 (2012) https://opg.optica.org/ol/abstract.cfm?URI=ol-37-6-1067.

Candès, E. & Romberg, J. Sparsity and incoherence in compressive sampling. Inverse Problems 23, 969. https://doi.org/10.1088/0266-5611/23/3/008 (2007).

Howland, G. A. Compressive sensing for quantum imaging (PhD thesis, University of Rochester, 2014).

Baraniuk, R. G. Compressive sensing [lecture notes]. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 24, 118–121 (2007).

Sher, Y. Review of algorithms for compressive sensing of images (2019). arXiv:1908.01642.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S. A., R. Kh.,and S. M. designed and directed project; K.H. performed the experiments and made the simulations. K.H. wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hassanzadeh, K., Ahmadi-Kandjani, S., Kheradmand, R. et al. Improving PSNR and computational efficiency in orthogonal ghost imaging. Sci Rep 15, 16194 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01283-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01283-w