Abstract

There is growing interest in next-generation semiconductor memory that combines high speed, large capacity, and non-volatility. Many types of emerging memory technologies, such as PCRAM and MRAM, are being developed utilizing 3D crossbar array structures to achieve high integration. In this type of structure, selectors are essential for blocking sneak current that bypasses cells during read operations. Additionally, selectors have been applied for processing, such as neuromorphic computing. As selectors, ovonic threshold switching (OTS) materials with a large ON/OFF current ratio and high amorphous stability are required. Additionally, it is crucial to design OTS materials without using highly toxic substances such as arsenic. Herein, we demonstrate that an Ag-Ga-Ge-Te (AGGT) amorphous film exhibits threshold switching with a large ON/OFF current ratio, rendering it an effective switching material for non-volatile memory. Ga was found to reduce the leakage current in the OFF state because the enhancement of ionicity lowered carrier mobility. Ag improved amorphous stability, leading to high endurance. Moreover, we determined that the co-addition of Ag and Ga to Ge-Te modifies the conduction mechanism from bulk-dominated to interface-dominated conduction. Overall, our results suggest that stronger ionicity and enhanced amorphous stability are key for developing superior selector materials. These findings are completely different from those associated with reported selector materials in which high covalency is a critical factor. Therefore, we believe that AGGT amorphous films represent a completely new paradigm for designing OTS materials. Furthermore, they can contribute to improving the performance and practicality of next-generation semiconductor memory and processing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In highly integrated next-generation semiconductor memory devices, chalcogenide-based amorphous thin films that exhibit ovonic threshold switching (OTS), where a sudden change from high to low resistance occurs above a certain threshold voltage, are expected to be used as selector materials1,2. As selectors, OTS materials with a large ON/OFF current ratio and high amorphous stability are required. For a high level of integration, the larger the sneak current, the lower the leakage current required3. High amorphous stability is required to prevent crystallization during repeated switching. Many previously reported chalcogenide selectors contain highly toxic substances, such as arsenic3,4,5,6, and it is desirable to eliminate the use of such substances. As selector materials free of arsenic, some Te-based materials have been proposed7,8,9,10,11. Herein, we demonstrate that an Ag-Ga-Ge-Te (AGGT) amorphous film exhibits an OTS effect with a much-reduced leakage current in the order of 10−9 A. We confirmed that the addition of Ga to Ge-Te reduces the leakage current in the OFF state and that the addition of Ag to Ge-Te enhances the stability of the amorphous phase. Therefore, the co-addition of Ga and Ag greatly enhances both the ON/OFF current ratio and endurance of Ge-Te amorphous OTS films. Lencer et al. characterized phase-change chalcogenides based on the degree of ionicity and covalency of bonding and proposed a map for phase-change materials12. Based on this map, Velea et al. reported that promising OTS material candidates fall in a narrow region characterized by lower ionicity and higher covalency than phase-change materials7. However, AGGT exhibited desirable OTS properties despite its much higher ionicity compared to previously reported Te-based OTS chalcogenides. The temperature dependence of the current-voltage characteristics revealed that AGGT exhibits interface-dominated conduction, rather than conventional bulk-dominated conduction. Overall, the presented results suggest that the ON/OFF current ratio and endurance can be improved by increasing ionicity and enhancing the stability of the amorphous phase, offering a new paradigm for designing OTS materials.

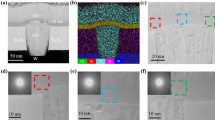

Dynamic transient current of AGGT

We prepared test devices with AGGT amorphous films as active layers. Additionally, we prepared test devices with Ge-Te (GT), Ag-Ge-Te (AGT), and Ga-Ge-Te (GGT) amorphous films as active layers to understand the effects of composition on resistive switching. The thickness of each active layer was 150 nm. The dynamic transient current and endurance measurements were performed using a unique single device. In the as-deposited state, all films were confirmed to be in an amorphous phase using XRD measurements (Supplementary Fig. 1). In the device integration process, a maximum temperature of 30 °C was reached following the deposition of the active layer. It is much lower than the crystallization temperature of each amorphous film (Supplementary Table 1). Therefore, it could be stated that all active layers were in an amorphous state before electrical testing. The compositions of target materials used in each active layer are listed in Supplementary Table 2. In this study, we detected the transient current during a 1 µs voltage pulse. As shown in Figure 1(a), the current increased abruptly when the voltage reached 1.5 V, which is indicative of the threshold switching behavior of the AGGT, where the threshold voltage (Vth) is 1.5 V. The ON current was measured to be approximately 3.7 × 10−3 A. Upon lowering the voltage back to 0 V, the device returned to the high-resistance state. The OFF current was read using a post pulse voltage of 0.6 V, which is approximately Vth/3. The measured OFF current was found to be on the order of 10−9 A, resulting in an ON/OFF current ratio in the order of 2.2 × 106, where the ON current/OFF current ratio was 3.7 × 10−3 A/1.7 × 10−9 A. Notably, the Vth measured in the 1 st cycle was the same as that measured in the 2nd cycle and beyond, indicating that no forming step was required for the AGGT device13. Subsequently, we evaluated the endurance of the AGGT device. Figure 1(b) presents the endurance as evaluated with a pulse voltage of 1.5 V for switching to the ON state and a pulse voltage of 0.6 V for reading the OFF current. After 105 cycles of switching, the OFF current drastically increased, indicating failure of the device. Figure 1(c) presents the transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image and the compositional mappings of the cross section of the AGGT device after failure. The TEM observation reveals that a partial crystallization occurred in the AGGT layer. The compositional mappings clearly showed that the crystallized part was found to be enriched in Ge and nearly depleted in Ag, indicating that the GeTe phase was formed by the crystallization. Therefore, we concluded that the drastic increase in the OFF current after 105 switching cycles was caused by the formation of the low-resistance GeTe crystalline phase. The crystallization is likely to be caused by the heat accumulated during the switching cycles. Since the degree of heat accumulation is largely affected by the insulating layer around the selector layer and applied pulse voltage, improving device structure or optimizing the shape of applied pulse voltage could enhance endurance. Specifically, reducing the pulse voltage duration or utilizing cross-point structure would be effective, as these approaches can suppress heat accumulation during operation and mitigate degradation. Moreover, these approaches align more closely with practical device operation and structure.

Properties of AGGT device. (a) Dynamic transient current measurement in the AGGT device when applying the threshold pulse voltage, where the dynamic current at the threshold voltage changed negligibly, even after 104 cycles. (b) Endurance behavior of the ON/OFF current ratio of the AGGT device, where VON indicates the amplitude of the pulse voltage for the ON state and Vread indicates the reading voltage for the OFF current. (c) TEM image and composition mappings of the cross section of the AGGT device after failure. A partial crystallization occurred in the AGGT layer (left figures). The atomic column image and diffraction patterns indicate that the crystalline phase is a GeTe phase. The crystallized part was enriched in Ge and almost depleted in Ag (right figures), where Ga distribution could not be evaluated because the Ga focused ion beam (FIB) was used to prepare the sample for TEM observation.

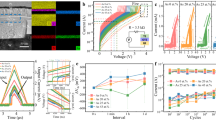

Effects of Ag and Ga

The same measurement procedures described above were also applied to the other layer compositions (GT, AGT, and GGT) to understand the effects of composition on OTS characteristics, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. The ON current/OFF current ratios at the beginning of measurement were 8.9 × 10−3 A/1.5 × 10−7 A, 11.4 × 10−3 A/3.7 × 10−7 A, and 3.5 × 10−3 A/8.6 × 10−8 A for the GT, AGT and GGT devices, respectively. Consequently, the ON/OFF current ratio values at the beginning of measurement for the GT, AGT, and GGT devices were determined to be in the order of 6.0 × 104, 3.1 × 104, and 4.1 × 104, respectively, which are smaller than that of the AGGT device. A much-reduced leakage current in the OFF state is the reason for the higher ON/OFF current ratio of the AGGT device. The endurance values of the GT, AGT, and GGT devices were found to be in the order of 4.0 × 102, 1.0 × 105, and 3.0 × 104, respectively. Endurance is defined as the number of cycles after which the ON/OFF current ratio clearly degrades by more than an order of magnitude. These results indicate that the addition of Ag or Ga alone to Ge-Te enhances the endurance of the OTS effect. Additionally, it was determined that the co-addition of Ag and Ga to Ge-Te significantly reduces the OFF current, resulting in an enhanced ON/OFF current ratio and endurance.

Bonding environment

The chemical bonding environment was evaluated using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). Figure 2 illustrates the XPS spectra of each sample for Te 4 d, Ge 3 d, Ag 3 d, and Ga 3 d. The Ge 3 d and Te 4 d peaks exhibit a negligible shift with the addition of Ag to Ge-Te, which can be attributed to the small amount of Ag. The calculated heteronuclear bond enthalpy based on Pauling’s Equation14 in the AGGT-based amorphous phase is presented in Supplementary Table 3. Parameters such as the homonuclear bond enthalpy and electronegativity of each element were obtained from the paper by Lankhorst et al.15. It is assumed that after high-enthalpy heteronuclear bonds are formed, and the remaining elements form homonuclear bonds. The calculated results suggest that in the AGT amorphous film, Ge-Te and Ag-Te bonds are formed, followed by the formation of Te-Te bonds between the remaining Te atoms. In GGT and AGGT, the Te 4 d peak shifts to a lower energy level, and the Ge 3 d peak exhibits a negligible shift. This implies that new Ga-Te bonds are formed in the GGT and AGGT. The heteronuclear bond enthalpy results described above imply that in the GGT amorphous film, Ge-Te, Ga-Te, and remaining Te-Te bonds are preferentially formed. Additionally, electron transfer to Te anions from Ga cations should occur because the electronegativity of Ga is lower than that of Ge and Te, resulting in the Te 4 d peak shifting to a lower binding energy. This may lead to electrons becoming more localized around Te nuclei, which will change the chemical environment from covalency to ionicity. In AGGT, in addition to the Te 4 d peak shift observed in GGT, a Ga 3 d peak shift to lower binding energy was also observed, implying that differences exist in the chemical bonding environments around Ga between GGT and AGGT. This suggests an increase in ionicity around Ga caused by Ag. Highly ionic bonds localize electrons around each nucleus, reducing the overlap between adjacent electron densities. As a result, potential fluctuations at each position increase, hindering carrier transfer. Therefore, in AGGT, carrier transfer is further inhibited by scattering arising from potential fluctuations, leading to suppressed carrier mobility16,17. Because the resistance of the amorphous films considered in this study was too high to measure carrier mobility via Hall effect measurement, we estimated carrier mobility from Seebeck coefficients and resistivity at room temperature. The specific calculation method is described in the Methods section. The carrier mobility at room temperature for each amorphous film was estimated as follows: AGGT, 8.7 × 10−5 cm2/Vs; GT, 5.1 × 10−3 cm2/Vs; AGT, 2.6 × 10−3 cm2/Vs; and GGT, 2.1 × 10−4 cm2/Vs. All films exhibited p-type conduction. When Ag or Ga was added to Ge-Te, a decrease in the carrier mobility was observed. However, Ga addition resulted in a greater reduction in carrier mobility compared to Ag addition. It is worth noting that the AGGT amorphous film exhibited the smallest carrier mobility among all films. Figure 2(e) presents the correlation between the OFF current and carrier mobility, indicating that the OFF current tends to decrease as the carrier mobility decreases. These results suggest that the co-addition of Ag and Ga results in higher ionicity and can significantly reduce the carrier mobility of amorphous Ge-Te, resulting in reduced leakage current in the OFF state and enhanced ON/OFF current ratio.

XPS spectra. XPS spectra of (a) Te 4 d, (b) Ga 3 d, (c) Ge 3 d, and (d) Ag 3 d for each amorphous film. The color-coding of the spectra is as follows: AGGT, red; GT, blue; AGT, green; and GGT, pink. (e) Correlation between OFF current and carrier mobility. In the XPS spectra, the peak shift of Te is observed only in films containing Ga (GGT and AGGT), indicating that Ga enhances the ionicity of Te. The enhancement of Ga ionicity by Ag is also observed in AGGT. Therefore, Ag/Ga co-doping is the most effective approach for reducing leakage current.

Amorphous stability

This section discusses the endurance of threshold switching. In the GT amorphous film, the OFF current gradually increased with the number of cycles, and an order of magnitude increase in the OFF current was observed within 103 cycles. This phenomenon can be attributed to the occurrence of partial crystallization. In contrast, the addition of Ag and/or Ga resulted in a nearly constant OFF current over a larger number of cycles, suggesting that the enhancement of amorphous stability is a plausible reason for the improvement of endurance. The stability of the amorphous phase was evaluated based on the activation energy required for crystallization, which was calculated using the Kissinger method18,19. The crystallization temperatures of each amorphous film were measured at different heating rates (5, 7, 10, and 15 °C/min). The method of determining them is described in the Methods section, and their values are listed in Supplementary Table 1 and plotted in Figure 3(a). The activation energy values were derived from the slope of the plotted data. In the Kissinger method, the relationship between the crystallization temperature and activation energy required for crystallization is defined by the following equation:

where α denotes the heating rate, Tp indicates the crystallization temperature, R is the gas constant, and Ec denotes the activation energy required for crystallization. Ec was determined to be 356, 236, 363, and 252 kJ/mol for AGGT, GT, AGT, and GGT, respectively. The activation energies of the films containing Ag (AGT and AGGT) were significantly higher than those of the films without Ag (GT and GGT). This result clearly shows the positive effect of Ag in improving amorphous stability. Figure 3(b) presents the correlation between the activation energy required for crystallization and endurance, indicating that the thermal stability of the amorphous phase is a key factor for enhancing the endurance of selector operation and that the addition of Ag is highly effective for improving the thermal stability of the amorphous phase of the GT film.

Electrical conduction mechanism

In this section, we evaluate the electrical conduction mechanism of the GT, AGT, GGT, and AGGT amorphous films. Initially, we investigate whether the electrical conduction mechanism matches the Poole–Frenkel conduction mechanism, which is one of the most common electrical conduction mechanisms observed in OTS materials20,21,22. We evaluated the I-V curves using the following Poole–Frenkel emission model23:

where \(\:J\) denotes the current density, \(\:E\) is the applied electric field, \(\:q\) is the elementary charge, \(\:{\phi\:}_{B}\) denotes the voltage barrier that an electron must cross to move from one atom to another in the crystal, \(\epsilon\) symbolizes the dynamic permittivity, \(\:{k}_{B}\) is Boltzmann’s constant, and T is temperature. According to Eq. (2), the value of ln(I/V) would increase linearly as a function of V1/2 when the conduction mechanism is the Pool–Frenkel conduction model. Figure 4 (a) shows ln(I/V) plots as a function of V1/2. For the GT, AGT, and GGT devices, a linear relationship could be observed in the V1/2 range from 0.2 to 0.6, indicating a good fitting of the Poole–Freckle conduction model, while the AGGT device was far from linear. This implies that the AGGT device exhibits a different conduction mechanism from the other three devices. The activation energy for the carrier transport as a function of the applied voltage is presented in Figure 4(b). The temperature-dependent I-V characteristics of the devices and log current vs 1/kT plots used to calculate the activation energy are displayed in Supplementary Fig. 10. It is evident that the activation energy decreases as the applied voltage increases in the GT, AGT, and GGT devices, indicating that the electrical conduction mechanism is Poole–Frenkel conduction. In contrast, in the AGGT device, the activation energy increases as the applied voltage increases. This also implies that the AGGT device exhibits a different conduction mechanism compared to the other devices, which could be the reason for its large ON/OFF current ratio.

Investigation of AGGT conduction mechanism. (a) ln(I/V) as a function of V1/2 for verifying the Poole–Frenkel conduction. The ln(I/V) plots as a function of V1/2 could be fitted linearly for the GT, AGT, and GGT devices, but not for the AGGT device. (b) The activation energy required for the carrier transport. The activation energy in the GT, AGT, and GGT devices decreased as the applied voltage increased, but in the AGGT device, the activation energy increased, implying that the conduction mechanism in the AGGT device is different from the other devices. (c) ln(I) as a function of V for verifying the Schottky conduction in the AGGT device. It is clearly fitted to the linear line, proving that the conduction mechanism of the AGGT is the Schottky conduction. (d) Schottky barrier height \(\phi_B\) and ideality factor n as a function of temperature in the AGGT device.

Therefore, we attempted to investigate the ln(I) as a function of V in the AGGT device to verify the Schottky conduction model, in which electrons can be thermally activated by the semiconductor material (in this study, AGGT). The relationship between current and voltage in this model is expressed as follows24:

where k is the Boltzmann constant, n is the ideality factor, and Is denotes the saturation current. According to Eq. (3), the value of ln(I) increases linearly as a function of V. For the AGGT devices, a linear relationship can be observed clearly, as shown in Figure 4 (c), implying a good fitting of the Schottky conduction model. Note that the I-V curve measured again at 313 K after cooling from 353 K showed the same curves as the initial measurement at 313 K (Supplementary Fig. 11), suggesting that no structural and interfacial changes could be induced by such a low annealing temperature (~ 353 K), and the observed temperature dependence of I-V characteristics exhibits the characteristics of the AGGT device. The slope of the first linear region of forward bias in the ln(I) versus V plot yields the value of the ideality factor n as follows:

where k is the Boltzmann constant, n is the ideality factor, and Is denotes the saturation current. Additionally, the barrier height \(\phi_B\) can be calculated using the following equation:

where A denotes the contact area and A* is Richardson’s constant, which is 120 A cm−2K−2. Here, \(\phi_B\) was determined to be 0.465 eV, and the ideality factor was approximately 3.850 at 313 K. Figure 4(d) presents the Schottky barrier height \(\phi_B\) and ideality factor n as functions of temperature in the AGGT device. The ideality factor is typically considered as a measure of the conformity of the thermionic emission (TE) of diodes and it is required that the value is close to unity. A high value of n indicates the deviation of the conduction mode from TE to thermionic field emission (TFE) as a result of a tunneling current. As the temperature increases, additional carriers can be activated in the AGGT and the carriers can also acquire sufficient energy to cross the high barrier. Consequently, the tunneling effect can be weakened, contributing to a TE conduction process. Therefore, the ideality factor tends to approach unity with increasing temperature and \(\phi_B\) increases with a decrease in the ideality factor. The results of our analysis reveal that the AGGT device exhibits the Schottky TFE conduction mode. When Ag and Ga are co-doped, the AGGT device exhibits a Schottky contact property with the W electrode, which is different from the undoped GT device and may directly contribute to the improved switching performance of the AGGT device. The transition from Poole-Frenkel to Schottky conduction is likely due to the changes in the trap center caused by structural modification in the amorphous thin film—such as defect formation due to Ag and Ga doping—resulting in the domination of interfacial conduction over bulk conduction. However, the reasons for this distinctive conduction mechanism should be studied further by investigating the local structure of the amorphous materials using detection tools such as Raman spectroscopy or X-ray techniques, as well as by investigating the interfacial properties within the device.

Conclusions

We found that the leakage current in the OFF state and the endurance of threshold switching were greatly enhanced by the co-addition of Ag and Ga to a binary Ge-Te film. The co-addition of Ag and Ga was highly effective at reducing the OFF current of the AGGT device, resulting in the enhancement of the ON/OFF current ratio. The reduction in the OFF current was considered to be a result of the decrease in carrier mobility caused by enhanced ionicity. Compared with other reported OTS materials, AGGT exhibits a low OFF current and a high ON/OFF current ratio despite its larger cell size, as shown in Supplementary Table 5. We believe this is a distinct merit of AGGT, which possesses high ionicity and a unique conduction mechanism. The endurance of threshold switching in the Ge-Te amorphous film was improved by the individual addition of either Ag or Ga, which can be attributed to the enhancement of amorphous stability. In particular, the addition of Ag can greatly increase the activation energy required for crystallization, which greatly improves endurance. Furthermore, it was determined that the co-addition of Ag and Ga causes the electrical conduction mechanism to differ significantly from the Poole–Frenkel mechanism, which is common in OTS materials. We believe that further clarifying the technical position of AGGT by evaluating additional performance metrics, such as switching speed and threshold voltage drift, is important. Nevertheless, our results suggest that controlling the ionicity and amorphous stability of a material to produce interface-dominated conduction is a promising strategy for developing superior OTS selectors.

Methods

Film sample preparation

Films were deposited on a Si/SiO2 substrate via magnetron sputtering using alloy targets. The sputtering radio frequency (RF) power was fixed at 6 W. The sputtering pressure was 1.0 Pa under an Ar gas flow rate of 10 sccm. The compositions of the alloy targets were measured using scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy and are summarized in Supplementary Table 2.

Device preparation

The appearance of the device used to evaluate threshold switching properties is presented in Supplementary Fig. 4(a). Several devices were fabricated on a Si/SiO2 substrate. Each device was fabricated by depositing each layer on the substrate via sputtering deposition and combining the conventional photo-etching technique with the focused ion beam (FIB) technique, where FIB drilling was used to create a hole with a diameter of 500 nm in the SiO2 layer. In this study, a W layer was used for both the top and bottom electrodes. Supplementary Fig. 4 (b) presents a schematic illustration of the cross-section of the device.

Summary of the relationship between device sample and measurements

In this study, three devices (named A, B, and C) were fabricated for each selector layer composition and used for the measurements. These devices, with the same composition selector layer, were simultaneously fabricated on the same substrate. The correspondence between the devices and measurements is summarized below.

Device A

・Dynamic transient current measurements: Fig. 1 (a) and Supplementary Fig. 2 (a) (c) (e).

・Endurance measurements: Fig. 1 (b) and Supplementary Fig. 2 (b) (d) (f).

・TEM observation: Fig. 1 (c).

Device B

・Temperature dependence of DC I-V: Fig. 4, Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11.

Device C

・Pulse voltage measurement to confirm holding voltage (Vh): Supplementary Fig. 7.

Dynamic transient current and endurance measurement with pulse voltage

We investigated the dynamic transient responses of threshold switching of the test devices by using a B1530A waveform generator/fast measurement unit attached to a Keysight B1500A semiconductor analyzer. The waveforms applied for pulsed I-V measurements are presented in Supplementary Fig. 5, where the threshold voltage Vth was used for ON current measurement and the voltage Vth/3 was used for OFF current measurement. Under the voltage pulse, the sampling time of the dynamic current was 20 ns. Supplementary Fig. 6 presents a typical time-dependent pulse voltage (black) and dynamic current (red) under various pulse voltage amplitudes, where the amplitude of the voltage pulse was varied in steps of 0.2 V. The switching voltage under which the dynamic current abruptly increased was evaluated.

TEM observation

TEM observation was performed using a JEM-F200 (JEOL). The acceleration voltage was 200 kV, and the composition analysis was performed by Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy. Sample preparation was performed via the FIB technique using FB2200 (Hitachi), and the prepared sample thickness was 100 nm.

Characterization of bonding environments

XPS characterization was performed using a PHI 5000 Versa Probe III (ULVAC-PHI) with a monochromatized Al Kα radiation source. The surfaces of the thin film samples for XPS measurement were pre-cleaned using Ar+ to remove the oxidized layers. Peak shift correction was performed based on the C1s peak at 284.6 eV.

Carrier mobility characterization

The thin films used for measuring carrier mobility were fabricated at a thickness of 150 nm via RF sputtering on a Si substrate with a thermally oxidized layer. The carrier mobility of each sample was calculated according to the following equations25:

where ρ denotes the resistivity, e is the electron charge, n is the carrier concentration, µ is the carrier mobility, N indicates the effective density of states, S is the Seebeck coefficient, and k is the Boltzmann constant. In principle, the carrier concentration can be directly measured using a Hall-effect measurement system (TOYO Corporation ResiTest8308), but the resistivity of the amorphous thin films in this study was too high to determine the carrier concentration. Therefore, we first measured the carrier concentration and the Seebeck coefficients of crystallized thin films with the above instrument and determined the effective density of states. For thin films in the amorphous state, we measured the Seebeck coefficients and estimated the carrier concentration by using the value of the effective density of the crystallized states determined using the above process. The values for career mobility estimation: resistivity, Seebeck coefficient, effective density of states, and carrier concentration, are listed in Supplementary Table 4.

Crystallization temperature measurement

The crystallization temperatures were determined by monitoring the electrical resistance while the thin films were heated. When the thin film is in an amorphous state, its electrical resistance is high, but when crystallization occurs, the electrical resistance drops abruptly. In this study, the crystallization temperature was defined as the point at which the electrical resistance drops. Supplementary Fig. 3 shows an example of the data obtained by measuring the electrical resistance while heating a thin film.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The simulation codes supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Anbarasu, M. et al. Nanosecond threshold switching of GeTe6 cells and their potential as selector devices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 143505 (2012).

Lee, M. J. et al. A plasma-treated chalcogenide switch device for stackable scalable 3D nanoscale memory. Nat. Commun. 4, 2629 (2013).

Zhu, M., Ren, K. & Song, Z. Ovonic threshold switching selectors for three-dimensional stackable phase-change memory. MRS Bull. 44 (9), 715–720 (2019).

Devulder, W. et al. A combinatorial study of SiGeAsTe thin films for application as an ovonic threshold switch selector. Thin Solid Films. 753, 139278 (2022).

Intel 3D XPoint Analysis Report. Tech Insights (2017). https://www.techinsights.com

Garbin, D. et al. Composition Optimization and Device Understanding of Si-Ge-As-Te Ovonic Threshold Switch Selector with Excellent Endurance. In Proc. IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 34.1.1–35.1.4 (2019).

Velea, A. et al. Te-based chalcogenide materials for selector applications. Sci. Rep. 7, 8103 (2017).

Yoo, J. et al. Te-based binary OTS selectors with excellent selectivity (> 105), endurance (> 108) and thermal stability (> 450°C). In Proc. IEEE Symposium on VLSI Technology 207–208 (2018).

Chekol, S. A. et al. A C–Te-based binary OTS device exhibiting excellent performance and high thermal stability for selector application. Nanotechnology 29, 345202 (2018).

Yoo, J. et al. Steep slope Field-Effect transistors with B–Te-Based ovonic threshold switch device. IEEE J. Electron. Devices Soc. 6, 821–824 (2018).

Woo, C. H. et al. IEEE,. Low-voltage (~ 1.3V), Arsenic Free Threshold Type Selector with Ultra High Endurance (> 1011) for High Density 1S1R Memory Array. In Proc. 2021 Symposium on VLSI Technology 1–2 (2021).

Lencer, D. et al. A map for phase-change materials. Nat. Mater. 7, 972–977 (2008).

Pierre, N. et al. Toward ultimate nonvolatile resistive memories: the mechanism behind ovonic threshold switching revealed. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay2830 (2020).

Pauling, L. The Nature of the Chemical Bond 3rd edition. Cornell University Press, New York (1960).

Lankhorst, M. H. R. Modelling glass transition temperatures of chalcogenide glasses. Applied to phase-change optical recording materials. J. Non-Cryst Solids. 297, 210–219 (2002).

Ren, G. K. et al. Enhancing thermoelectric performance in hierarchically structured bicuseo by increasing bond covalency and weakening carrier–phonon coupling. Energy Environ. Sci. 10, 1590–1599 (2017).

Zhang, X. & Pei, Y. Manipulation of charge transport in thermoelectrics. Npj Quantum Mat. 2, 68 (2017).

Heireche, M. M., Belhadji, M. & Hakiki, N. E. Non-isothermal crystallisation kinetics study on Se90 – xIn10Sbx (x = 0, 1, 2, 4, 5) chalcogenide glasses. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 114, 195–203 (2013).

Kissinger, H. E. Variation of peak temperature with heating rate in differential thermal analysis. J. Res. Natl. Bureau Stand. 57, 217–221 (1956).

Nardone, M., Simon, M., Karpov, I. V. & Karpov, V. G. Electrical conduction in chalcogenide glasses of phase change memory. J. Appl. Phys. 112, 071101 (2012).

Wei, C. C. et al. A study on OTS-PCM pillar cell for 3-D stackable memory. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 65, 5172–5179 (2018).

Daniele, I. Threshold switching mechanism by high-field energy gain in the hopping transport of chalcogenide glasses. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 78, 035308 (2008).

Lim, E. W. & Ismail, R. Conduction mechanism of Valence change resistive switching memory: A survey. Electronics 4, 586–613 (2015).

Jyothi, I. et al. Temperature dependency of Schottky barrier parameters of Ti Schottky contacts to Si-on-Insulator. Mater. Trans. 54, 1655–1660 (2013).

Gotoh, T. Effect of annealing on carrier concentration in Ge2Sb2Te5 films. Can. J. Phys. 92, 681–683 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.M., Y.Sh.; material development, Y.M.; selector device evaluation, Y.Sh.; carrier mobility and amorphous stability analysis, Y.M., K.K.; XPS analysis, E.T.; TEM analysis, N.T.; conduction mechanism investigation, Y.Sh., Y.Su.; writing-original draft preparation, Y.M.; writing-review and editing, Y.Sh., Y.Su.; supervision, F.S., Y.Su.; project administration, K.C.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Matsushita, Y., Shuang, Y., Karakida, K. et al. Arsenic-free Ge-Te-based ovonic threshold switching material with reduced leakage current. Sci Rep 15, 22014 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01323-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01323-5