Abstract

Microbially-induced carbonate precipitation (MICP) using a urea-hydrolyzing enzyme (urease) is a next-generation, environmentally friendly cementation technique. The isolation of excellent urease-producing bacteria for MICP is essential for establishing this technique. We have demonstrated a highly effective screening method for identifying promising bacteria suitable for MICP. In our selective plate, MICP-positive bacteria formed a CaCO3 halo around the colony on the plate, which was clearly distinguishable. Furthermore, we found that the CaCO3 formation activity of each bacterium was strongly correlated with the strength of the solidified sand samples. This technique is a novel approach for screening bacteria suitable for biocementation or MICP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cement and concrete are key materials in the construction industry, and their use is expected to increase with recent urbanization worldwide. However, the production of cement causes substantial emission of greenhouse gases such as CO21. It is not realistic to replace a large amount of current cement materials with next-generation alternatives in a short period of time. Nonetheless, we should not stop the exploitation of new materials or techniques because unprecedented global warming is increasing and the unprecedented “era of global boiling” has finally arrived, as the UN chief once warned. An alternative technique for cementation or solidification is to employ a biological method using microbes or enzymes2. Biocementation, specifically indicating microbially induced carbonate precipitation (MICP), involves urea hydrolysis to produce bicarbonate ion, which leads to CaCO3 formation in the presence of Ca2+ ions3. Formed CaCO3 can work as a cementing material that solidifies silica sand4, natural soil5,6,7, contaminated soil8,9,10,11, and mine waste12. MICP has currently attracted much attention as an alternative, bio-based, and eco-friendly cementation technique13,14,15, which can be used to actual application in a large scale16,17. Therefore, it is quite important to isolate promising bacteria for MICP in an effective manner.

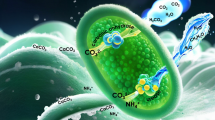

Since the first step in MICP is the hydrolysis of urea catalyzed by urease produced by bacteria, screening for promising bacteria has only focused on urease activity. In conventional isolation methods, bacteria are first isolated from natural soil and water samples on normal agar plates. Subsequently, the isolated bacteria were assessed for urease activity by a chromogenic reaction using pH indicators such as phenol red, where the color of the solution is changed by the pH change caused by ammonia formation during urea hydrolysis. Using this method, we can obtain urease-producing bacteria with high activity if useful bacteria are present in the samples, and rapid, efficient, and high-throughput evaluation methods have been reported18,19. However, even when a strain exhibiting high urease activity is obtained, the bacterial strain is not always effective for MICP. Although the reason for the unexpected and disappointing performance is unclear, there would be a possible reason for that. Calcium carbonate precipitation by bacteria or MICP-based biomineralization involves many reaction factors, including: (a) urease activity, (b) carbonic anhydrase activity20, (c) functional groups on/around the cell surface working as a template for mineralization21,22,23,24, (d) metabolites accelerating mineral formation25 (Fig. 1A). It indicates screening methods that focus only on urease activity may occasionally miss the mark. Bacterial strains that evenly satisfy these multiple factors with good balance would work as a powerful biocatalyst in MICP.

In the present study, we have demonstrated an all-inclusive, straightforward, and highly effective screening method to find promising bacteria suitable for MICP, labelled, “MICP-positive bacteria.” This method is based on the concept of the halo assay, in which indicators appear around a positive bacterial colony. In our strategy, MICP-positive bacteria were assumed to form CaCO3 around their colonies on plates containing urea and CaCl2 (Fig. 1B). In this concept, the positive bacteria strain is not only showing urease activity but also exhibiting important factor which is crucial for MICP as mentioned above. This implied that the halo-forming strain inherently possessed important properties and key factors for MICP. This study demonstrates a novel screening methodology for isolating promising bacterial strains using previously isolated bacteria with known properties.

Materials and methods

Bacteria strains

Pararhodobacter sp26,27, Sporosarcina sp., Virgibacillus sp., and Arthrobacter creatinolyticus MTCC 56042829, all with high urease activity were employed in this study to demonstrate the applicability of our approach. Escherichia coli which has a negligible urease activity was used as a negative control. Pararhodobacter sp. and E. coli were used as models of marine bacteria, whereas Sporosarcina sp., Virgibacillus sp., and Arthrobacter creatinolyticus MTCC 5604 were used to represent terrestrial bacteria.

Selective plate for MICP-positive bacteria

Three types of selective plates were prepared to demonstrate the feasibility of this screening method for isolating bacteria suitable for MICP: one for marine bacteria and two for terrestrial bacteria. The selective plate for marine bacteria (plate M) was prepared based on ZoBell 2216E medium (5 g/L polypepton, 1 g/L yeast extract, 0.1 g/L FePO4, 1.5% agar, prepared using artificial sea water, adjusted at pH 7.8 with NaOH, simply described as ZoBell medium), supplemented with urea (final conc. 0.5 M) and CaCl2 (final conc. 0.05 M) sterilized by 0.22 µm filter to avoid urea hydrolysis and unexpected calcium precipitation by autoclave sterilization. We adjusted urea concentration to 0.5 M considering the avoidance of deactivation of bacterial cell and providing sufficient concentration to form adequate CaCO3 based on our previous research5,30. Calcium ion concentration was set to 0.05 M because higher concentration would result in unexpected precipitation. Similarly, we prepared a selective plate for terrestrial bacteria (plate T-1) based on NH4-YE medium (20 g/L yeast extract, 10 g/L (NH4)2SO4, 1.5% agar, prepared using 0.13 M Tris-HCl buffer at pH 9), instead of the ZoBell medium. Furthermore, another type of selective medium for terrestrial bacteria (plate T-2) was prepared based on standard medium (5 g/L peptone, 2.5 g/L yeast extract, 1 g/L glucose, at pH 7), instead of NH4-YE medium.

Pararhodobacter sp. was shown to exhibit high efficiency in urease-based MICP (MICP-positive) in our previous studies10,12, whereas E. coli did not have urease activity for MICP (MICP-negative). Pararhodobacter sp. and E. coli, representing marine bacteria, were pre-cultured for 16 h in ZoBell, followed by dilution by 106-fold, inoculation on the selective plate M, and culturing at 30 °C for 72 h. Sporosarcina sp. and Virgibacillus sp., representing terrestrial bacteria, were precultured in NH4-YE liquid medium, followed by inoculation on selective plate T-1 in the similar manner of the marine bacteria.

A white, halo-like precipitate that formed around the colony of Pararhodobacter sp. in plate M was removed and heated to dissolve a small amount of the accompanying agar gel. Thermostable β-agarase (6 units, Nippon Gene Co. Ltd., Japan) was added to the dissolved gel, followed by heating at 50 °C for 10 min to degrade the agarose. The solution containing the degraded agarose was discarded, and the precipitate was washed with water and freeze-dried overnight. The dried white precipitate was analyzed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM; JSM-IT200 InTouchScope, JEOL, Japan) equipped with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS).

Urease activity and semiquantitative evaluation of CaCO3 formation activity of bacteria

The urease activity of the bacteria was evaluated in solution to monitor urea hydrolysis. Bacterial cells were precultured in each liquid medium (ZoBell for Pararhodobacter sp. and E. coli, NH4-YE for Sporosarcina sp. and Virgibacillus sp.), and then cultured in 100 ml of that medium at 30 °C for 24 h. Urease activity (i.e., urea hydrolytic activity) of the culture was measured by monitoring the increase in electric conductivity using a compact EC meter (LAQUAtwin EC-33, HORIBA, Ltd., Kyoto, Japan) according to our previous report30.

Calcium carbonate formation activity of the bacteria was evaluated semi-quantitatively. Liquid culture medium (ZoBell for Pararhodobacter sp. and E. coli, NH4-YE for Sporosarcina sp. and Virgibacillus sp.) containing 0.5 M urea and 0.05 M CaCl2 were prepared in a similar manner to the plates M and T-1 as described above without adding agar. Bacterial cells on the plate were picked up and inoculated in the above liquid cultures, followed by culturing cells at 30 °C and 160 rpm for 24 h. After cultivation associated with CaCO3 formation, the samples were centrifuged (12,000 rpm, 5 min) to separate the formed CaCO3 from the solution, followed by the measurement of the Ca2+ ion concentration in the solution using a calcium ion meter (LAQUAtwin Ca-11, HORIBA, Ltd., Kyoto, Japan). The amount of formed CaCO3 was calculated from the decrease in Ca2+ ions in the solution.

The precipitate of CaCO3 was freeze dried and subjected to powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) and SEM analysis. The XRD analysis was conducted by MiniFlex (Rigaku Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) with Co Kα radiation at 40 kV, 15 mA, 6.5°/min, and the obtained data were analyzed by SmartLab Studio II (Rigaku Co., Ltd.).

Solidification of silica sand by bacteria

Sand solidification by microbially-induced carbonate precipitation (MICP) was performed as described in a similar manner to our previous report10,26,31 using Pararhodobacter sp., E. coli, Sporosarcina sp., and Virgibacillus sp. Zobel medium was used for Pararhodobacter sp. and E. coli, while NH4-YE medium was used for Sporosarcina sp. and Virgibacillus sp.

Oven-dried Mikawa silica sand (No. 4, 40 g) was divided into three portions and placed in a 30 mL syringe (diameter = 2.5 cm, height = 7 cm) in three layers, followed by 20 hammer blows for packing sand particles of each layer. A bacterial cell suspension (10 ml, OD600 = 1) was injected into the syringe and allowed to stand for 20 min to permit better fixation of the bacteria into the sand particles, followed by draining the solution from the outlet, leaving the solution 2 mm above the sand surface. Then, cementation solution (6 mL; 0.5 M urea, 0.5 M CaCl2, 3 g/L nutrient broth) was added to the syringe. The solution was then drained from the outlet, maintaining 2 mL of the solution above the surface to maintain the sand in the immersed condition. Experiments were conducted in an incubator at 30 °C for 14 days.

After solidification test, the samples were removed from the syringe by cutting. A needle penetration test was conducted to estimate uniaxial compressive strength (UCS) of the cemented sand. The estimated UCS was calculated via regression analysis using the relationship shown in Eq. 1, which was developed by analyzing 114 natural soft rock samples and 50 cemented soils26, where y is the estimated UCS (kPa) and x is the penetration gradient (N/mm) determined by the penetration resistance and penetration depth.

Results and discussion

Targeting selective plate for MICP-positive bacteria

MICP-based biomineralization involves many reaction factors, including (a) urease activity, (b) carbonic anhydrase activity for bicarbonate production, (c) functional groups on the cell surface working as templates for mineralization, and (d) metabolites accelerating mineral formation, as depicted in Fig. 1A. Although CaCO3 formation depends on the combined factors mentioned above, almost all bacteria for MICP are usually isolated based “only on urease activity”. Therefore, we developed a novel and all-inclusive screening method focusing on the CaCO3 forming ability of bacteria on the plate. In our approach, the selective plate medium contained urea and CaCl2 to directly detect CaCO3 formation by bacteria on the plate. Bacterial cells capable of producing large amounts of CaCO3 efficiently hydrolyze urea to bicarbonate and ammonia. The formation of bicarbonate ions was accelerated by carbonic anhydrase. Acidic functional group on the cell surface and/or extracellular polymeric substances such as -COO− and -SO3−212232, and metabolites produced from cells25 would facilitate CaCO3 formation. Promising strains possessing these functions efficiently formed CaCO3 around or outside their cells, resulting in the formation of a halo around the colony (Fig. 1B). Different types of selective plates were prepared for the marine (plate M) and terrestrial bacteria (plates T-1 and T-2).

First, we investigated the feasibility of our approach using plate M and two types of model bacteria: Pararhodobacter sp. and E. coli. Pararhodobacter sp. is known to have the ability to form a large amount of CaCO3, providing sufficient solidification of sand specimens with great strength in our previous research10,26,31,33 whereas E. coli does not have urease or biomineralization activity. Figure 2A shows a selective plate inoculated with Pararhodobacter sp. and E. coli. We observed a white halo around the colonies of Pararhodobacter sp. in the photograph from the bottom side of the plate, whereas defined shapes of colonies without a halo were found in E. coli. From the top, we could clearly see a yellow colony of Pararhodobacter sp. surrounded by a white precipitate, similar to an egg cooked sunny-side-up. On the other hand, E. coli produced white colonies without halos.

The white precipitate around the yellow colony was CaCO3 formed by the action of Pararhodobacter sp. To confirm this, we removed the white precipitate with surrounding agar gel from the plate M, followed by the dissolution of agarose by β-agarase. The resulting white material was analyzed using SEM-EDS. Spherical precipitates were observed in the samples, which showed relatively high Ca and Mg contents (Fig. 2B). Therefore, the white precipitate can be ascribed to composite minerals such as magnesium calcite formed by urea hydrolysis in the presence of magnesium ions in plate M, which was prepared using artificial seawater. It can be concluded from the results in Fig. 2 that promising marine bacteria for MICP can be isolated easily and effectively using our selective plate.

We successfully developed a selective plate for screening MICP-positive bacteria in marine environments. These bacteria could be used for artificial beach nourishment and coral preservation. Terrestrial bacteria can be used for MICP-based solidification of loose ground and slopes. Thus, we attempted to demonstrate the applicability of the present system to identify promising strains on land using a similar selective plate based on NH4-YE medium (plate T-1) in place of ZoBell medium. In our previous study, we isolated two types of ureolytic bacteria, Sporosarcina sp. and Virgibacillus sp., from the soil in Hokkaido, Japan. These two bacteria were used to validate our methodology for isolating MICP-positive terrestrial bacteria. We observed a halo around the colony of Sporosarcina sp., whereas no halo was found around the colony of Virgibacillus sp. (Fig. 3A). This indicated that Sporosarcina sp. could be categorized as an MICP-positive terrestrial bacterium capable of forming an adequate amount of CaCO3, on the other hand, Virgibacillus sp. would not possess sufficient activity for CaCO3 formation. Furthermore, we examined other types of selective plates for terrestrial bacteria prepared using a standard medium (plate T-2). We observed a halo around the colonies of Sporosarcina sp. and Arthrobacter creatinolyticus (Fig. 3B), both of which are effective bacteria for MICP28,29. These results clearly indicate that our approach can be expanded to many types of bacterial cultures, simply by supplementation with urea and calcium chloride along with nutrient source, considering bacterial growth environments including pH and salinity.

Criteria to select bacteria for MICP

In the system of urea-based CaCO3 formation, researchers usually measure the urease activity to determine whether isolated bacteria can potentially be used for MICP-based biocementation. However, as mentioned above, CaCO3 formation is affected not only by urease activity, but also by several other factors. Therefore, we aimed to develop reliable guidelines for the selection of useful bacteria. First, we investigated the urease activity of the four bacteria by conventional method (Fig. 4). Virgibacillus sp. showed the highest urease activity among the investigated strains, followed by Sporosarcina sp. and Pararhodobacter sp., whereas E. coli showed negligible activity as expected. If we selected bacteria based only on urease activity, Virgibacillus sp. would be the most promising strain for MICP. However, one of the most important factors to achieve higher strength in MICP is the adequate formation of CaCO3 to solidify sand specimens33,34, not urease activity.

Therefore, we evaluated these bacteria in terms of CaCO3 formation ability in a solution containing urea and Ca2+ ions. Since the accurate quantification of CaCO3 formed on a small scale would be difficult, we checked the decrease in Ca2+ ion concentration in the solution, which indirectly indicated the formation of CaCO3 (or other insoluble carbonates such as MgCO3). As shown in Fig. 5A, the decrease in Ca2+ ion concentration was higher in Pararhodobacter sp. and Sporosarcina sp. than in Virgibacillus sp. while E. coli gave negligible decrease, indicating that Pararhodobacter sp. and Sporosarcina sp. can produce a larger amount of CaCO3 for MICP. Comparing the urea activity (Fig. 4) and CaCO3 formation (Fig. 5A) of Sporosarcina sp. and Virgibacillus sp., we clearly found the inconsistency, that is, the fact that higher urease activity does not always result in higher amount of CaCO3 formation. Then, we analyzed the white precipitate formed by Pararhodobacter sp. (Figure S1, Supporting Information) using XRD and SEM, and found that magnesium calcite was formed35 (Fig. 5B).

Finally, we solidified the silica sand, which is the most important goal, using the four types of bacteria: Pararhodobacter sp., E. coli, Sporosarcina sp., and Virgibacillus sp. Figure 6 shows the estimated UCS value of each specimen, that is, the strength of the solidified sand. Pararhodobacter sp. gave the highest UCS value among these bacteria, while Sporosarcina sp. showed the second strongest value. Virgibacillus sp. resulted in moderate solidification contrary to our expectations, and no solidification was observed in E. coli. Notably, the trend in the estimated UCS of the solidified sand specimen (Fig. 6) was very similar to that of the decrease in the Ca2+ ions (Fig. 5A). This indicates that we can easily predict the promising bacteria for MICP just by checking the decrease in Ca2+ ions in a precipitation test. As the sand solidification test requires several weeks (usually at least two weeks) to achieve sufficient strength, this simple and easy approach is quite useful for screening target bacteria. If researchers select bacterial strains based only on urease activity (Fig. 4), where Virgibacillus sp. showed higher urease activity than Pararhodobacter sp., this would result in the false selection of promising bacterial species.

Therefore, we propose an efficient screening protocol. First, several promising bacteria can be isolated using a special selective plate whereby promising bacterial colonies form a white halo around the colony. Carbonate precipitation tests can then be performed in a solution containing urea, CaCl2, and the selected bacteria to evaluate CaCO3 formation semi-quantitatively. Finally, we can isolate useful bacteria for solidification. However, it should be noted that some bacterial strains cannot grow under relatively high concentration of urea (0.5 M), which could possibly lead to the loss of a good candidate.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated highly efficient screening method for promising bacteria suitable for MICP using selective plate containing urea and CaCl2, where MICP-positive bacteria formed a CaCO3 halo around the colony. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the CaCO3 formation activity of each bacterium was correlated with the strength of the solidified sand samples. The present work would contribute to bio-based and next-generation solidification techniques.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Habert, G. et al. Environmental impacts and decarbonization strategies in the cement and concrete industries. Nat. Reviews Earth Environ. 1, 559–573. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-020-0093-3 (2020).

Whiffin, V. S., van Paassen, L. A. & Harkes, M. P. Microbial carbonate precipitation as a soil improvement technique. Geomicrobiol. J. 24, 417–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490450701436505 (2007).

De Muynck, W., De Belie, N. & Verstraete, W. Microbial carbonate precipitation in construction materials: A review. Ecol. Eng. 36, 118–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2009.02.006 (2010).

Mwandira, W. et al. Solidification of sand by Pb(II)-tolerant bacteria for capping mine waste to control metallic dust: case of the abandoned Kabwe mine. Zambia Chemosphere. 228, 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.04.107 (2019).

Gowthaman, S., Mitsuyama, S., Nakashima, K., Komatsu, M. & Kawasaki, S. Biogeotechnical approach for slope soil stabilization using locally isolated bacteria and inexpensive low-grade chemicals: A feasibility study on Hokkaido expressway soil, Japan. Soils Found. 59, 484–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sandf.2018.12.010 (2019).

Zhang, K. et al. Microbial–induced carbonate precipitation (MICP) technology: a review on the fundamentals and engineering applications. Environ. Earth Sci. 82, 229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-023-10899-y (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. Improved methods, properties, applications and prospects of microbial induced carbonate precipitation (MICP) treated soil: A review. Biogeotechnics 3, 100123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bgtech.2024.100123 (2025).

Achal, V., Pan, X., Zhang, D. & Fu, Q. Bioremediation of Pb-contaminated soil based on microbially induced calcite precipitation. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 22, 244–247. https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.1108.08033 (2012).

Achal, V., Pan, X., Lee, D. J., Kumari, D. & Zhang, D. Remediation of Cr(VI) from chromium slag by biocementation. Chemosphere 93, 1352–1358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.08.008 (2013).

Mwandira, W., Nakashima, K. & Kawasaki, S. Bioremediation of lead-contaminated mine waste by Pararhodobacter Sp. based on the microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation technique and its effects on strength of coarse and fine grained sand. Ecol. Eng. 109, 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2017.09.011 (2017).

Taharia, M. et al. Microbial induced carbonate precipitation for remediation of heavy metals, ions and radioactive elements: A comprehensive exploration of prospective applications in water and soil treatment. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 271, 115990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2024.115990 (2024).

Mwandira, W. et al. Efficacy of biocementation of lead mine waste from the Kabwe mine site evaluated using Pararhodobacter Sp. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. Int. 26, 15653–15664. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-04984-8 (2019).

Song, M. et al. A review on the applications of microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation in solid waste treatment and soil remediation. Chemosphere 290, 133229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.133229 (2022).

Kumar, A. et al. Application of microbial-induced carbonate precipitation (MICP) techniques to remove heavy metal in the natural environment: A critical review. Chemosphere 318, 137894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.137894 (2023).

Carter, M. S. et al. Microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation by Sporosarcina pasteurii: a case study in optimizing biological CaCO3 precipitation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 89, e0179422. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.01794-22 (2023).

Cuthbert, M. O. et al. A field and modeling study of fractured rock permeability reduction using microbially induced calcite precipitation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 13637–13643. https://doi.org/10.1021/es402601g (2013).

Graddy, C. M. R. et al. Diversity of Sporosarcina-like bacterial strains obtained from Meter-Scale augmented and stimulated biocementation experiments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 3997–4005. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.7b04271 (2018).

Cui, M. J., Teng, A., Chu, J. & Cao, B. A quantitative, high-throughput urease activity assay for comparison and rapid screening of ureolytic bacteria. Environ. Res. 208, 112738. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2022.112738 (2022).

Medina Ferrer, F., Hobart, K. & Bailey, J. V. Field detection of urease and carbonic anhydrase activity using rapid and economical tests to assess microbially induced carbonate precipitation. Microb. Biotechnol. 13, 1877–1888. https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-7915.13630 (2020).

de Oliveira Maciel, A., Christakopoulos, P., Rova, U. & Antonopoulou, I. Carbonic anhydrase to boost CO2 sequestration: improving carbon capture utilization and storage (CCUS). Chemosphere 299, 134419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.134419 (2022).

Sarayu, K., Iyer, N. R. & Murthy, A. R. Exploration on the biotechnological aspect of the ureolytic bacteria for the production of the cementitious materials–a review. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 172, 2308–2323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-013-0686-0 (2014).

Tourney, J. & Ngwenya, B. T. The role of bacterial extracellular polymeric substances in geomicrobiology. Chem. Geol. 386, 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2014.08.011 (2014).

Zhang, W., Ju, Y., Zong, Y., Qi, H. & Zhao, K. In situ Real-Time study on dynamics of microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation at a Single-Cell level. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 9266–9276. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b02660 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Microbial-induced calcium carbonate precipitation: influencing factors, nucleation pathways, and application in waste water remediation. Sci. Total Environ. 860, 160439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.160439 (2023).

Sato, A. et al. Glycolytic intermediates induce amorphous calcium carbonate formation in crustaceans. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 197–199. https://doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.532 (2011).

Danjo, T. & Kawasaki, S. Microbially induced sand cementation method using Pararhodobacter Sp. Strain SO1, inspired by beachrock formation mechanism. Mater. Trans. 57, 428–437. https://doi.org/10.2320/matertrans.M-M2015842 (2016).

Fujita, M., Nakashima, K., Achal, V. & Kawasaki, S. Whole-cell evaluation of urease activity of Pararhodobacter Sp. isolated from peripheral beachrock. Biochem. Eng. J. 124, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bej.2017.04.004 (2017).

Ramesh, R. et al. Screening and production of a potent extracellular Arthrobacter creatinolyticus urease for determination of heavy metal ions. J. Basic. Microbiol. 54, 285–295. https://doi.org/10.1002/jobm.201200561 (2014).

Sujiritha, P. B. et al. Valorization of tannery solid wastes for sustainable enzyme induced carbonate precipitation process. Chemosphere 308, 136533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.136533 (2022).

Chen, M., Gowthaman, S., Nakashima, K., Takano, C. & Kawasaki, S. Baseline investigation on soil solidification through biocementation using airborne bacteria. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 11, 1216171. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2023.1216171 (2023).

Nawarathna, T. H. K., Nakashima, K., Fujita, M., Takatsu, M. & Kawasaki, S. Effects of cationic polypeptide on CaCO3 crystallization and sand solidification by Microbial-Induced carbonate precipitation. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 6, 10315–10322. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b01658 (2018).

Nawarathna, T. H. K. et al. Artificial fusion protein to facilitate calcium carbonate mineralization on insoluble polysaccharide for efficient biocementation. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 9, 11493–11502. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c03730 (2021).

Gowthaman, S., Nakashima, K. & Kawasaki, S. Durability analysis of bio-cemented slope soil under the exposure of acid rain. J. Soils Sediments. 21, 2831–2844. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-021-02997-w (2021).

Lai, H. et al. Factors affecting the effectiveness of biocementation of soil. Biogeotechnics 2, 100087. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bgtech.2024.100087 (2024).

Long, X., Ma, Y. & Qi, L. Biogenic and synthetic high magnesium calcite - a review. J. Struct. Biol. 185, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsb.2013.11.004 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by JSPS KAKENHI (grant number JP21H03627), JSPS Bilateral Joint Research Projects (grant number JPJSBP 120207701), and Shiraishi Foundation of Science Development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.N. and Y.S. designed and conceived this study. Y.S., A.Y., W.M, and P.B.S. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. M.F., M.C., S.G., T.H.K.N. were involved in the discussion to improve this work. N.R.K, C.T., and S.K. verified the technique and carefully edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nakashima, K., Sugawara, Y., Fujita, M. et al. In situ mineral formation on a plate for direct and efficient screening of bacteria suitable for biocementation. Sci Rep 15, 18706 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01350-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01350-2