Abstract

We first demonstrate a nonaqueous rechargeable battery using uranium and iron as active materials. This uranium-iron battery achieves an open-circuit voltage of approximately 1.3 V, exhibits stable cycling performance, and delivers a good Coulombic efficiency of 86 ± 2%. These characteristics suggest a promising avenue for utilizing depleted uranium in innovative applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Depleted uranium (DU), a byproduct of enriched uranium (EU) production for nuclear fuel, contains a lower isotopic concentration of U-235 (approximately 0.25%) compared with natural uranium (approximately 0.72%). This reduced concentration renders DU unsuitable for use in light-water nuclear reactors as it lacks the necessary neutron absorption cross-section. Although DU has been proposed as a blanket fuel for fast-breeder reactors (FBRs), the commercially viability of FBR technology remains a distant prospect. Consequently, there is no alternative application except for military purposes, and a large amount of DU (approximately 1.6 million tons) is stored worldwide1.

In the 2000s decade, Shiokawa et al. proposed the concept of a redox flow battery (RFB) using uranium as an active material for developing new applications of DU2,3,4 The design utilized redox couples: UV/UVI (UVO2+/ UVIO22+) at the positive electrode and UIII/UIV (U3+/U4+) at the negative electrode. They found that uranium complexes with β-diketonate ligands show relatively good redox behaviours in organic solvents5,6, and adopted organic solvents for the uranium-based RFBs7,8,9,10 because of instability of UIII and UV species in aqueous solutions. However, there are no reports about the specific performance of these batteries experimentally assembled, while the numerical investigation of the ideal battery performance was only reported11 Recent studies have reported the redox behaviors of uranium in several ionic liquids (ILs). Notably, in 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide ([EtMeIm+][Tf2N–]) diluted with N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), quasi-reversible redox couples of UIII/UIV and UV/UVI were observed at room temperature12,13.

Today, the need for large-capacity batteries such as RFBs is increasingly demanded to store electricity unstably generated by renewable energy14 Power systems from solar, wind, and other sources is affected by weather conditions and has the instability of fluctuating power generation. To stabilize the power supply in this situation, output controls via electrochemical energy storage devices such as rechargeable batteries are necessary, and the development of new energy storage technologies is attracting attention15,16,17,18,19 This study aims to demonstrate the feasibility of uranium-based rechargeable batteries as a pathway to achieving net-zero carbon emissions with effective utilization of DU.

To design a new uranium-based battery, we selected a mixture of 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride ([EtMeIm+]Cl) and DMF as the electrolytic solution. DMF was selected for its wide electrochemical window (− 3.8 to + 1.3 V vs. Fc/Fc+) and its high solubility of uranium tetrachloride (UIVCl4), the starting material for uranium. Additionally, [EtMeIm+]Cl was expected to function as a supporting electrolyte and stabilizing reagent for UIVCl4 in the organic solution. In a previous study, we reported that the formation of the uranium chloride complex (UIIICl63– and UIVCl62–) possibly enhanced the reversibility of the UIII/UIV redox reaction in a mixture of 1:1 v/v [EtMeIm+][Tf2N–] – DMF12.

Results and discussion

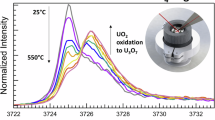

To reveal how a change in ILs affects the electrochemical behavior of UIVCl4, we performed cyclic voltammetry (CV) at sweep speed of 10 mVs–1 on 10 mM UIVCl4 in 1 M [EtMeIm+]Cl – DMF solution. As shown in Fig. 1, the reduction and oxidation waves (Epc and Epa) of UIVCl4 were respectively − 1.073 V and − 0.981 V. The difference between the peak potentials was therefore 92 mV. When the redox couple is reversible, the DEp value is independent of the sweep speed, DEp ≈ (59/n) mV at 298 K, where n is the electron transfer number. The obtained value is close to the peak potential difference of 59 mV (n = 1), suggesting that the U redox reaction is one-electron transfer couple (UIII/UIV). We have also performed CVs at sweep speeds of 20 and 100 mVs–1 (Figure S1). These values increased with sweep speed (Table S1). Since the value was larger than the DEp value of reversible redox reaction and depended on the sweep speed, the redox reaction is not fully reversible but quasi-reversible. Furthermore, we investigated the chemical state of UIV in the 1 M [EtMeIm+]Cl – DMF via UV-vis absorption spectroscopy as shown in Figure S2. The spectrum shape of 10 mM UIVCl4 in 1 M [EtMeIm+]Cl – DMF is similar to that of a solid sample containing UIVCl62–20,21. This suggests that UIVCl4 reacts with Cl– in the 1 M [EtMeIm+]Cl – DMF to form UIVCl62–, which exhibits a quasi-reversible UIII/UIV redox reaction. Given its formal potential E0’ ((Epc + Epa)/2) is − 1.02 V (vs. Ag/Ag+), the UIII/UIV redox couple is a favorable candidate for use in a negative electrolytic solution of uranium-based batteries.

To achieve a high open-circuit voltage (OCV) in the new uranium-based battery (uranium-iron (UFe) battery), we adopted the FeII/FeIII redox couple for the positive electrolytic solution instead of UVO2+/UVIO22+. This adoption was based on the expectation that the redox potential of FeII/FeIII would be more positive than that of the uranyl couple (− 1.1 V vs. Fc/Fc+). Figure 1 shows a cyclic voltammogram of 10 mM of 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrachloroferrate(III) ([EtMeIm+][FeIIICl4–]) in the 1 M [EtMeIm+]Cl – DMF solution. The reduction and oxidation waves of iron were found at + 0.393 (Epc) and + 0.470 V (Epa), respectively. The difference between Epc and Epa was 77 mV, comparable to FeIIICl4– ionic liquids in deionized water22. The DEp values of Fe redox couple at sweep speeds of 20 and 100 mVs–1 were 83 and 111 mV, respectively (Figure S3 and Table S1). Therefore, the Fe redox reaction is quasi-reversible one-electron transfer couple (FeII/FeIII). It suggests that the FeII/FeIII redox couple was quasi-reversible and the formal potential E0’ is + 0.432 V (vs. Ag/Ag+). It is noted that, to our best knowledge, the redox behavior of [EtMeIm+][FeIIICl4–] has only been reported in the aqueous solution22.

As described above, we found the quasi-reversibility of UIII/UIV and FeII/FeIII redox reactions in the 1 M [EtMeIm+]Cl – DMF system. The formal potential difference between these two couples was approximately 1.4 V, which was larger than the potential difference between UIII/UIV and UVO2+/UVIO22+. The value (1.4 V) represents the ideal OCV for a UFe battery based on the following reaction.

During charging, reaction (1) proceeds to the right, while during discharging, it proceeds to the left. To reveal the potential of the UFe battery, we experimentally demonstrate the new battery by using a small H-type cell, as described in Figure S4. Since this study focuses on the assembly of a rechargeable battery using uranium as the active material, an H-type cell with a simple structure was chosen as the best prototype configuration for the evaluation of the rechargeable battery. The UFe battery was assembled using 0.1 M UIV in the 1 M [EtMeIm+]Cl – DMF solution (3 mL) and 0.1 M of FeII in the 1 M [EtMeIm+]Cl – DMF solution (3 mL) as a negative and positive electrolytic solution, respectively. All preparations and assembly steps were conducted in a glove box in an argon (Ar) gas atmosphere. The positive electrolytic solution was prepared by constant-current electrolysis of iron wire at 10 mA in an H-type cell with 1 M [EtMeIm+]Cl – DMF solution. This procedure was selected because a complete electrolytic reduction of FeIII to FeII was not achievable using the [EtMeIm+][FeIIICl4–] in 1 M [EtMeIm+]Cl – DMF solution owing to a considerable voltage drop, likely caused by a decrease in reactant concentration. To mitigate this issue, the iron wire was employed as a sufficient source of iron ions. As shown in Figure S5, the UV-vis spectrum of the prepared positive electrolytic solution significantly differs from that of the sample solution containing [EtMeIm+][FeIIICl4–] (named “FeIII sample”). On the other hand, the positive electrolytic solution shows a similar spectrum characteristic to the FeIII sample after electrolytic reduced. These facts indicate that the iron in the positive electrolytic solution is likely to be divalent and possibly forms FeIICl42–. Whereas we recognize the necessity of understanding the chemical characterization of iron in the nonaqueous solution, we used the solution for the following experiments to assemble a prototype of the UFe battery.

Figure S6 (a) and (b) show optical images of the UFe battery before and after charging at 3 mA for approximately 5 min, respectively. The negative electrolytic solution color changed from green to dark purple, likely due to the valence change of uranium from UIV to UIII. Similarly, the color of the positive electrolytic solution shifted from light yellow to deep yellow, indicating the oxidation of FeII to FeIII.

Figure 2 shows the charge/discharge curves of the UFe battery cell using a glass fiber membrane (pore size, 0.5 μm) as a separator at a charge current of 3 mA and a discharge current of 0 − 2 mA. Given that both the negative and positive electrolytic solutions contained 0.3 mmol of active material, the theoretical capacity of the cell was 8.0 mAh. Thus, the charge ratio after 15 min of charging at a current of 3 mA was approximately 9%. The curve for a 0 mA discharge shows OCV and was about 1.3 V. This is close to the expected value from the formal potentials obtained by CV (Fig. 1). The relatively stable OCV demonstrates the battery’s ability to store electricity. In practice, the UFe battery successfully powered a red LED, as shown in Fig. 3. The LED remained illuminated for over 5 min after the UFe battery was charged at 3 mA for 15 min, resulting in the first-ever experimental demonstration of a uranium-based rechargeable battery.

A comparison of the discharging curves presented in Fig. 2 shows that the cell voltage decreased as the discharge current increased, primarily due to the relatively high internal resistance of the battery. This resistance likely originates from the H-type cell configuration (e.g., small size of carbon felt electrode, long distance between electrodes). Understanding the causes of these voltage drops will be critical for improving the battery’s performance.

Figure 4 shows the cycle characteristics of the UFe battery when charging at 3 mA and discharging at 2 mA. To prevent the decomposition of the electrolytic solvent, the terminal voltage was set to 0.5 V. The Coulombic and energy efficiencies for 10 cycles were calculated from equations S1 and S2 (see SI). The Coulombic efficiency remained nearly constant across 10 cycles (Figure S7) with an average value of 86 ± 2%. This value was relatively good but lower than the ideal 100%. Since there was little change in the Coulombic efficiency during 10 cycles, it is unlikely that electrolytic solutions were mixed over the separator during the cycling test. Therefore, the loss of Coulombic efficiency may be attributed to internal discharge caused by contamination of the negative electrolyte into the positive electrolyte during the assembly process. We consider that the Coulombic efficiency can be improved by the modification of the assembling process of the UFe battery. The energy efficiency also has minimal variation over 10 cycles (Figure S7) with an average value of 42 ± 1%. The low efficiency is considered to be due to the high internal resistance of the cell. Although further optimization is needed for the UFe battery, the performance of the uranium-based battery was experimentally evaluated for the first time in this study, and it was shown that uranium can work as an active material in a nonaqueous rechargeable battery.

Conclusions

We successfully demonstrated a rechargeable battery using uranium as an active material. UIVCl62– was formed by chloride ions added in the electrolytic solution, and a stable UIII/UIV redox couple was confirmed. We assembled a small size of a UFe battery which consists of a UIV negative electrolytic solution and FeII positive electrolytic solution. The UFe battery exhibited stable charge/discharge characteristics with a good Coulombic efficiency over at least 10 cycles. Although this study employed a small cell, scaling up the UFe battery is feasible with a deeper understanding of the origins of voltage drops and optimization of the battery configuration. Although DU is relatively low in radioactivity and has a specific activity of less than two-thirds that of natural uranium, it is a radioactive material and must be tested in an appropriate controlled area in accordance with the law. In developing a large-scale battery in the future, we believe it is necessary to evaluate shielding and other safety measures. This work demonstrates the potential for UFe batteries to contribute to the peaceful utilization of DU in synergy with renewable energy sources.

Experimental

Reagents

The ionic liquids, 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride ([EtMeIm+]Cl) and 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium Tetrachloroferrate(III) ([EtMeIm+][FeIIICl4–]) were purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. (Japan). 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl) imide ([EtMeIm+][Tf2N–]; purity, > 99.5%; H2O < 100 ppm) was purchased from Ionic Liquids Technologies (Germany). N, N-Dimethylformamide (DMF; H2O < 10 ppm) was purchased from FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Co. (Japan). DMF and [EtMeIm+][Tf2N–] were dried using molecular sieves 3 A (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Co.). Uranium(IV) chloride (UIVCl4) was synthesized via a solid/gas reaction as described in a previous study12 All experimental procedures were conducted in an Ar or dry N2 gas atmosphere. Carbon felt (> 95%; 280 g/sm) and iron wire (φ1.0 m; 99.5%) were purchased from The Nilaco Corporation (Japan).

Sample preparation for cyclic voltammetry and UV-vis spectroscopy

To prepare a solution containing 10 mM of UIVCl4, the appropriate amounts of UIVCl4 powder were dissolved in a 1 M [EtMeIm+]Cl – DMF solution. Similarly, a solution containing 10 mM FeIIICl4– was prepared by mixing [EtMeIm+][FeIIICl4–] with a 1 M [EtMeIm+]Cl – DMF solution. All procedures were performed in an Ar gas atmosphere using a glove box.

Electrochemical measurements

Electrochemical measurements were performed in a glove box under an Ar gas atmosphere using an ECstat-302 analyzer (EC Frontier Co., Ltd., Japan). For cyclic voltammetry, a commercial three-electrode electrochemical cell (VB3; EC Frontier Co., Ltd.) was used. The working electrode (WE) was a glassy carbon (GC) disk electrode (GC-6355; electrode surface of 0.07 cm2; EC Frontier Co., Ltd.), polished with diamond abrasives before use. The counter electrode was a platinum spiral wire (CE-200; EC Frontier Co., Ltd.). The reference electrode (RE) was an Ag/Ag+ electrode (RE-5 A; EC Frontier Co., Ltd.) in 0.1 M AgCl – 1 M [EtMeIm+]Cl – DMF solution; the RE was connected to the sample solution through a porous glass frit as a liquid junction. A two-electrode electrochemical method was used to evaluate the performance of the UFe battery in a small H-type cell (VB10; EC Frontier Co., Ltd.). As shown in Figure S4, carbon felt was used for both the negative and positive electrodes. The Pt wire was used as the current collector, attached to the carbon felt electrodes. Glass fiber membranes with a pore size of 0.5 μm (GC-50; thickness, 190 μm thickness; Advantec Toyo Kaisha, Ltd., Japan) were used as separators.

Preparation of the positive electrolytic solution containing FeII

To prepare a positive electrolytic solution containing FeII, an electrolytic leaching method was used with an iron wire in a conventional H-type cell (VB9; EC Frontier Co., Ltd.). Glass filter membranes with a pore size of 5–10 μm were used as separators. A polished spiral iron wire served as the anode and was immersed in 15 mL of 1 M [EtMeIm+]Cl – DMF solution as the anolyte. On the opposite side, 0.2 M [EtMeIm+][FeIIICl4–] in 1 M [EtMeIm+]Cl – DMF solution (15 mL) was used as the catholyte. The overall reaction during electrolysis is represented as follows:

The cathode was carbon felt. Constant-current electrolysis was performed at 10 mA for more than 6 h under stirring of both the anolyte and catholyte. Notably, a complete reduction of FeIII in the catholyte to FeII was not achieved a dramatic voltage drop, likely caused by a decrease in reactant (FeIII) concentration. To obtain a relatively pure FeII-containing solution for demonstrating the UFe battery, the anolyte after electrolysis was used as the positive electrolytic solution containing approximately 0.1 M FeII. All procedures were conducted under Ar gas or dry N2 gas atmosphere.

UV-vis spectroscopy

The chemical states of UIV and Fe were confirmed by UV-vis spectroscopy using V-730 (JASCO Corporation, Japan).

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Uranium and Depleted Uranium, Information Library of World Nuclear Association. Accessed February 26, (2025). https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/nuclear-fuel-cycle/uranium-resources/uranium-and-depleted-uranium.

Shiokawa, Y., Yamana, H. & Moriyama, H. An application of actinide elements for a redox flow battery. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 37, 253–256 (2000).

Shiokawa, Y., Yamamura, T., Watanabe, N. & Umekita, S. Utilization of actinide as cell materials. JAERI-Tech, 17. (2002).

Yamana, H. et al. Utilization of actinide as cell materials–effective utilization of uranium as battery active Material–. JAERI-Tech, 18. (2002).

Yamamura, T. et al. Enhancements in the electron-transfer kinetics of uranium-based redox couples induced by tetraketone ligands with potential chelate effect. J. Phys. Chem. C. 111, 18812–18820 (2007).

Waldschmidt, P., Riedhammer, J., Hartline, D. R., Heinemann, F. W. & Meyer, K. Homoleptic acetylacetonate (acac) and β-Ketoiminate (acnac) complexes of uranium. Inorg. Chem. 62, 2013–2023 (2023).

Seeber, R. & Zanello, P. Solvent effects on the redox potential of the uranium(VI)–uranium(V) couple. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans., 601–603. (1985).

Kim, S. Y. et al. Electrochemical studies on [U(dmso)9]4+ and [UO2(dmso)5]2+ (dmso = dimethyl sulfoxide) complexes in DMSO. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 39, 441–444 (2002).

Afonso, M. L. et al. Electrochemical behaviour of uranium (IV) in DMF at vitreous carbon. Electrochim. Acta. 54, 7318–7323 (2009).

Takao, K., Takao, S., Ikeda, Y., Bernhard, G. & Hennig, C. Uranyl–halide complexation in N,N-dimethylformamide: Halide coordination trend manifests hardness of [UO2]2+. Dalton Trans. 42, 13101–13111 (2013).

Shiokawa, Y., Yamamura, T. & Shirasaki, K. Energy efficiency of an uranium Redox-Flow battery evaluated by the Butler–Volmer equation. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 75, 137–142 (2005).

Ouchi, K., Komatsu, A., Takao, K., Kitatsuji, Y. & Watanabe, M. Electrochemical studies of uranium (IV) in an ionic Liquid–DMF mixture to build a redox flow battery using uranium as an electrode active material. Chem. Lett. 50, 1169–1172 (2021).

Takao, K., Ouchi, K., Komatsu, A., Kitatsuji, Y. & Watanabe, M. Securing reversibility of UVO2+/UVIO22+ redox equilibrium in [emim]Tf2N-Based liquid electrolytes towards uranium redox-Flow battery. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 27, e202300787 (2024).

Luo, X. Z. et al. Trimetallic metal–organic frameworks and derived materials for environmental remediation and electrochemical energy storage and conversion. Coord. Chem. Rev. 461, 214505 (2022).

Chen, M., Zhang, Y., Xing, G., Chou, S. L. & Tang, Y. Electrochemical energy storage devices working in extreme conditions. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 3323–3351 (2021).

Xu, M. et al. Cationic vanadium vacancy-enriched V2 – xO5 on V2C MXene as superior bifunctional electrocatalysts for Li-O2 batteries. Sci. China Mater. 65, 1761–1770 (2022).

Xu, H. et al. V2C MXene enriched with -O termination as high-efficiency electrocatalyst for lithium-oxygen battery. Appl. Mater. Today. 27, 101464 (2022).

Kothandam, G. et al. Recent advances in Carbon-Based electrodes for energy storage and conversion. Adv. Sci. 10, 2301045 (2023).

Wang, C. et al. Accelerating lithium ion transport via increasing the entropy of the electrolyte for stable lithium metal batteries. J. Energy Chem. 99, 384–392 (2024).

Wacker, J. N. et al. Uranium(IV) chloride complexes: UCl62– and an unprecedented U(H2O)4Cl4 structural unit. Inorg. Chem. 56, 9772–9780 (2017).

Hashem, E. et al. Emission spectroscopy of uranium(iv) compounds: A combined synthetic, spectroscopic and computational study. RSC Adv. 3, 4350–4361 (2013).

Zafar, A., Imtiaz-ud-Din., Ahmed, S., Bucˇar, D. K., Tahirc, M. N. & Palgrave, R. G. Synthesis, structural analysis, electrochemical and magnetic properties of tetrachloroferrate ionic liquids. New. J. Chem. 45, 13429–13440 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M. W., K. U. and K. O. synthesized UCl4. K. U. performed the electrochemical measurements of the uranium and iron reactions. K. O. conducted the electrochemical measurements of the UFe battery. K. O. wrote the original draft, and all authors contributed to its revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ouchi, K., Ueno, K. & Watanabe, M. The rechargeable battery using uranium as an active material. Sci Rep 15, 18515 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01384-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01384-6