Abstract

The squirt flow in cracks or grain contacts at the pore scale is an important mechanism of seismic wave velocity dispersion and attenuation. We develop a simple and accurate analytical model for attenuation and dispersion caused by squirt flow between microcracks with different aspect ratios. The dual crack squirt flow model calculates compliance by considering the interconnectivity of two cracks with different aspect ratios. The crack diameter rather than radius was used as the characteristic length of the squirt flow, and the one-dimensional fluid pressure diffusion equation was used instead of the radial fluid pressure diffusion equation to describe the fluid squirt path. The analytical results of the dual crack model are in excellent agreement with the results obtained by numerical simulations. We use the dual crack model for inverse determination of multiple microcrack structures from pressure experimental data by applying the squirt flow model to each set of microcracks, and finally obtaining the attenuation and velocity dispersion in the rock. For the four examined rock samples, the predictions of the dual crack analytical model and the experimental measurements are in excellent agreement. The dual crack analytical model enables quantitative and qualitative analysis of seismic attenuation and velocity dispersion due to squirt flow between microcracks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Characterization of saturated porous rocks is often performed using seismic waves, which exhibit energy attenuation and velocity dispersion during propagation. The dispersion and attenuation of seismic waves in saturated porous rocks are caused mainly by fluid flow at different scales. Seismic waves passing through rock cause small deformations of the pores in the rock. The different compliances and thus deformations of adjacent pores give rise to local pressure gradients between these pores, and the pressure distribution within the pores results in a local flow of fluid until the fluid pressure reaches equilibrium1. Such localized flow at the pore scale, known as squirt flow, leads to a strong energy loss2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Many studies have proposed methods for quantifying the velocity dispersion and attenuation of seismic waves caused by squirt flow. The velocity dispersion and attenuation caused by squirt flow are closely related to the pore structure parameters, particularly the pore aspect ratio. A common approach for the analysis of squirt flow effects assumes that the rock pore space consists of two connected parts: the stiff torus pores, which occupy most of the volume, and microcracks, which are sensitive to pressure changes5,9,10. Spherical stiff pores and coin-shaped cracks11,12,13are also assumed to be present. In addition to analytical methods, many studies have used numerical methods to study squirt flow14,15,16,17,18. In contrast to the above idealized model of rock structures, rocks are filled with interconnected microcracks, which in some cases may even account for the majority of the rock pore space. However, analytical squirt flow models for dual crack geometric configurations are currently lacking, and few studies have investigated the frequency-related physical properties of these configurations.

The elastic properties of rocks are influenced by various factors, including porosity, pore structure, mineral composition, and fluid properties; among these, pore structure has a significant effect on rock characteristics. Quantitative characterization of pore structure is complicated by the intricate spatial distributions of rock pores. Consequently, ideal geometric shapes are frequently used in squirt flow models as approximations. The equivalent medium theory relates the structure of rock with its equivalent elastic properties. Currently, the most popular medium theories are the Kuster-Toksöz (KT)19, Mori-Tanaka (MT)20,21, self-consistent approximation (SCA)22,23,24,25 and differential effective medium (DEM) approaches26,27,28. Many studies have attempted to extract pore aspect ratios from experimental data via various methods29,30, and it is commonly assumed that rock contains only one or two types of pores. The aspect ratio inversion method assumes that the pore space of rocks is composed of a series of pores with different aspect ratios31,32,33,34. However, these methods ignore the squirt effect between microcracks and are not suitable for bridging the gap between microcrack-microcrack squirt models and real rocks.

In this study, we develop a simple and accurate analytical model for describing the attenuation and dispersion caused by squirt flow between microcracks with different aspect ratios. The model consists of two crack sections with the same diameter but different thicknesses, accounting for the influence of the connection of the two cracks on the elastic modulus. According to the dual crack geometrical configuration, the characteristic length of the squirt flow is changed from the radius of the compliant crack to its diameter; this makes it is more appropriate to use the one-dimensional fluid pressure diffusion equation rather than the radial fluid pressure diffusion equation, and also leads to the modification of the relaxation function of the compliant crack stiffness. Numerical simulations were used to validate the accuracy of the saturated dual crack analytical model. To show how dual cracks can be utilized in velocity prediction, we demonstrate the application of this method to real rock samples. Multiple microfracture structures are first obtained by inverting the experimental data from rock samples. A dual crack squirt flow model is then used for each group of microfractures to obtain a dual crack model that considers the distribution of multiple microfractures. Finally, the prediction results of the dual crack model are validated by comparison with the experimental measurements.

Methods

Analytical model of the dual crack model

In a squirt flow model, energy dissipation can be attributed to the diffusion of fluid pressure at the pore scale. The quantitative study of ideal rock considers three parts of the rock, namely the solid elastic matrix, stiff pores, and compliant cracks. Pores and cracks are interconnected and saturated with fluid. The deformation of compliant cracks caused by seismic waves and ultrasonic waves is greater than that of stiff pores (the deformation of small-aspect-ratio cracks in this study is greater than that of large-aspect-ratio cracks; this is similar to the classic models where small-aspect-ratio cracks are compliant cracks, whereas large aspect ratio cracks are stiff pores), giving rise to a fluid pressure gradient in the crack that generates a squirt flow that is closely related to the frequency of the propagating wave.

To date, an accurate analytical model that can construct a compliance contribution matrix between cracks with different aspect ratios has been lacking. The traditional torus stiff pore model is not sensitive to the crack aspect ratio, and the attenuation behavior of cracks partially connected to pores differs from that of the torus stiff pore model16. Therefore, we propose an approximate solution between cracks with different aspect ratios based on the analytical method proposed by Alkhimenkov and Quintal (2022)16 for constructing the compliance matrix of a crack partially connected to a pore.

The workflow for the calculation of the effective compliance matrix of the dual crack model, the compliant crack stiffness relaxation function and the bulk and shear moduli of the fully saturated model is as follows:

-

(1)

First, we calculate the bulk and shear moduli of the dual crack model in dry rock. This includes the moduli of the dry interconnected dual crack model and the moduli of the same model with the stiff crack only.

-

(2)

Second, we calculate the frequency-dependent bulk and shear moduli of the modified frame, i.e., the moduli of the stiff crack drying and the compliant crack saturated fluid in the model. The frequency-dependent crack stiffness is the key property which is obtained by calculating the relaxation function of crack stiffness due to squirt flow.

-

(3)

Finally, we calculate the bulk and shear moduli of the fully saturated dual crack model by applying the anisotropic Gassmann equation 35.

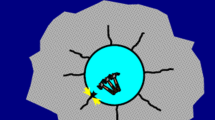

We utilize volume elements (RVEs) for the model configuration employed in this study, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The pore space is composed of coin-shaped cracks with two different aspect ratios, represented by two flat cylinders in the model. A crack with a small aspect ratio is set as a compliant crack, and a crack with a large aspect ratio is set as a stiff crack, where the aspect ratio is defined as the ratio of the height to the diameter of flat cylinders. When the seismic wave passes through, the two cracks are deformed to different degrees, and the fluid in the cracks creates a pressure gradient that can lead to squirt flow from the compliant crack to the stiff crack. The effective compliance matrix for the dry dual crack model shown in Fig. 1 can be written as (Step 1)

where \(S_{{mn}}^{{g}}\) is the compliance matrix of the solid grains and \({\left[ {{H_{mn}}} \right]_{{dry}}}\) is the compliance contribution matrix of the dry connected dual crack. The frequency-dependent effective compliance matrix (Step 2) of the modified frame after saturation of the compliant crack (the crack with a small aspect ratio) is given by

where \({\left[ {H_{{mn}}^{{s}}} \right]_{{dry}}}\) only contains the contributions of stiff cracks (the cracks with large aspect ratios in this model) and \({\left[ {H_{{mn}}^{\prime }\left( \omega \right)} \right]^{{mf}}}\) is the additional compliance matrix generated contribution due to the connection of two cracks with different aspect ratios and the saturation of the compliant crack. \(\omega\) is the angular frequency, and \({\left[ {H_{{mn}}^{\prime }\left( \omega \right)} \right]^{{mf}}}\) represents the frequency-related components. The effective stiffness matrix of the saturation model (Step 3) is given by

and the methods for the calculation of \({\alpha _m}\) and \({M_\alpha }\) are described in detail in Step 3: Stiffness of the fully saturated model.

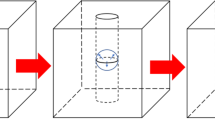

Step 1: Dry model compliance

In this study, three models with different geometrical configurations are shown for comparison: a classical torus of a stiff pore surrounding a coin-shaped crack (Fig. 2a), a stiff pore with a spherical shape that is partially connected to the crack (Fig. 2b), and a partially connected dual crack, where the crack with the largest aspect ratio is the stiff crack (Fig. 2c). The analytical method for the evaluation of the compliance matrix of these three models with different geometric configurations is constructed via micromechanics36. The key geometric features of the compliance contribution matrix for different pore spaces are obtained from three-dimensional numerical simulations, and the compliance contribution matrix of the dual crack model is constructed using the property contribution tensor of known geometric shapes.

By applying the method of constructing the compliance contribution matrix for complex geometries, the compliance contribution matrix for the drying model with a torus stiff pore enclosing the crack is constructed, obtaining good agreement with the accurate numerical solution. However, the components \({\left[ {{H_{33}}} \right]_{dry}}\), \({\left[ {{H_{44}}} \right]_{dry}}\), and \({\left[ {{H_{55}}} \right]_{dry}}\) of the model are only controlled by the torus, and the crack thickness does not affect the effective properties of the drying model17, which is not consistent with the real rock, where the crack thickness affects the effective elastic modulus. The compliance matrix for the model with a spherical stiff pore and connected a crack is calculated using the expression for the extended crack, except for components \({\left[ {{H_{33}}} \right]_{dry}}\), \({\left[ {{H_{44}}} \right]_{dry}}\) and \({\left[ {{H_{55}}} \right]_{dry}}\), which are controlled by the crack and the sphere at the same time, and the remaining \({\left[ {{H_{mn}}} \right]_{dry}}\), which is controlled by the sphere. The area of the extended crack is the same as the area of the pore space projected on the XY plane, the thickness is the same as that of the crack, and its compliance contribution component is denoted by \({\left[ {H_{{mn}}^{{ecr}}} \right]_{dry}}\).

The dual crack model proposed in this study follows the concept of the spherical model, where \({\left[ {{H_{33}}} \right]_{dry}}\), \({\left[ {{H_{44}}} \right]_{dry}}\) and \({\left[ {{H_{55}}} \right]_{dry}}\) are jointly controlled by dual crack, whereas \({\left[ {{H_{mn}}} \right]_{dry}}\) is controlled by the crack with the large aspect ratio. Its dry compliance contribution matrix is as follows:

where \({\left[ {H_{{mn}}^{s}} \right]_{dry}}\) is the component of large aspect ratio crack (as a stiff crack) and \({\left[ {H_{{mn}}^{{ecr}}} \right]_{dry}}\) is the component of the extended crack. The compliance contribution matrix for the modified frame is

where only the normal compliance component \({\left[ {H_{{33}}^{{ecr}}\left( \omega \right)} \right]^{mf}}\) is frequency-dependent. The compliance contributions of the stiff crack \({\left[ {H_{{mn}}^{{s}}} \right]_{dry}}\) and the compliance contributions of the modified frame \({\left[ {{H_{mn}}\left( \omega \right)} \right]^{mf}}\) are separated to obtain the contribution of the fluid-saturated compliant crack:

Equation (6) has the same structure as the compliance contribution matrix for cracks embedded in homogeneous elastic materials37,38, but the absolute values of the components are different. For simplicity, the normal crack apparent compliance \(Z_{n}^{{ap}}\) and apparent tangential crack compliance \({Z_{t}^{{ap}}}=\left[ {H_{{44}}^{\prime }} \right]_{{dry}}^{{mf}} \equiv \left[ {H_{{55}}^{\prime }} \right]_{{dry}}^{{mf}}\) are introduced:

Since the compliance contribution matrix of the compliant crack is described by only two parameters, the frequency-dependent normal component of the modified frame contribution matrix can be expressed as

where \({\phi _{c}}\) is the compliant porosity, \(K_{f}^{*}\left( \omega \right)\) is the frequency-dependent fluid bulk modulus, and \({K_{g}}\) is the bulk modulus of the solid grains. When the frequency applied to the strain boundary condition is low, the compliant crack is in a relaxed state:

At high frequencies, the compliant crack is in an unrelaxed state:

If the aspect ratio of the compliant crack is greater than 0.0025, then Eq. (10) must be supplemented with a small nonzero value.

At this point, the normal apparent crack compliance becomes

Equation (8) becomes

Step 2: Relaxation of the crack stiffness

Based on numerical studies, Alkhimenkov and Quintal (2022)16 reported that the characteristic frequencies of radial pressure diffusion and approximate one-dimensional pressure diffusion of fluid in compliant cracks are different, and the shapes of the attenuation curve 1/Q also differ. Radial fluid pressure diffusion expressions should be considered when the connecting surfaces between cracks and pores are large (torus or 8/9 torus). However, for the spherical pore model and the dual crack model in this study, the one-dimensional fluid pressure diffusion analytical solution provides a good approximation to the actual solution due to its small connecting surface:

where

is a function of the rheology of the layer39, and \({K_{f}}\) is the fluid bulk modulus. Using viscoelastic correspondence theory40, the final result is obtained as follows:

where \(\eta\) is the fluid shear viscosity and

where

where the characteristic length \({l^{sq}}\) of the squirt flow is the distance from the junction of the compliant crack and the stiff pore (crack) to the farthest edge of the compliant crack, which varies depending on the geometry of the model (as shown in Fig. 3), and the thickness of the squirt flow \({h^{sq}}\) is the crack aperture (cylinder height).

Step 3: Stiffness of the fully saturated model

The stiffness of the fully saturated model is calculated using the modified frame moduli via the anisotropic Gassmann equation 35:

For \(m=1,2,3\) and \({\alpha _4}={\alpha _5}={\alpha _6}=0\), where

where \({\phi _{s}}\) is the stiff pore porosity, \({K^*}\) is the generalized bulk modulus of the modified frame, and \({\alpha _m}\) is the Biot–Willis coefficient.

Porosity distribution of microcracks with different aspect ratios

The previous subsection presented the stiffness matrix constructed from the dry dual crack model, the fluid-induced stiffness relaxation, and the moduli in the saturated model. The results of numerical simulations of the geometrical configurations envisioned by the dual crack analytical model show that the dual crack analytical model can fully describe the physics of simple geometries. Therefore, the next step is to extrapolate to actual rock; otherwise, the model should not be applied to the rocks17. In this subsection, we introduce the application of the dual crack analytical model to rocks containing cracks with different aspect ratios.

To visualize the changes in the aspect ratio and density of microcracks after the rock is pressurized, we assume that there are four groups of microcracks in the rock, as shown in Fig. 4 by different colors, with the aspect ratio increasing and the number of cracks in the group decreasing sequentially from top to bottom. As the pressure increases, the microcracks close in order of aspect ratio from small to large, and the aspect ratio of unclosed microcracks decreases gradually.

Equivalent medium theory is an important tool for linking microscopic pore structures with the elastic properties of rocks. To obtain the relationship between the elastic moduli of rock and the cumulative crack density, this paper adopts commonly used equivalent medium models, including the KT model19, the MT model20, the DEM model26 and the SCA model41. Assuming that the rock contains only a set of coin-shaped microcracks with an aspect ratio \(\alpha\), the explicit analytical expressions42 for the geometric factors R and Q are

where \(\nu\) is the Poisson’s ratio, which is represented differently in different equivalent medium models. The total porosity \({\phi _{c}}\) of the microcrack can be written as \({\phi _{c}}=\frac{{4{\pi} \alpha }}{3}\varGamma ,\) where \(\varGamma\) is the crack density of microcracks in the rock. The relationship between the elastic moduli of the rock and the crack density \(\varGamma\) can be obtained by introducing R and Q into the equivalent medium model.

For the KT model, the crack density can be calculated by

and

where \(K_{{KT}}^{*}\) and \(G_{{KT}}^{*}\) are the KT equivalent bulk and shear moduli, respectively; \({K_{b}}\), \({G_{b}}\) and \({\nu _{b}}\) are the bulk and shear moduli, and the Poisson’s ratio of the rock grains, respectively. When all of the microcracks are closed, the moduli of the mineral grains can be obtained via the Voight‒Reuss‒Hill averaging equation 43.

For the MT model,

For the DEM model42,

For the SCA model,

For a set of microcracks containing only the aspect ratios \(\alpha =\frac{c}{a}\), where a and c are the long and short axes of the microcrack, respectively, the density \(\varGamma\) of this set of microcracks can be expressed as

where \(\varOmega\) is the rock volume and S is the number of microcracks in this group.

All of the above equivalent medium theories assume that rocks contain only one set of microcracks. Therefore, the calculations of the cumulative crack density \(\bar {\varGamma }\) for multiple-pore rocks based on these Eqs. 32,33 are not consistent with the structure of real rock for which the densities of the microcracks with different aspect ratios are different.

In pressure experiments, microcracks with different aspect ratios correspond to different crack densities \(\varGamma\), and rocks contain several groups of microcracks with different aspect ratios \(\alpha\). Equation (29) shows that the crack density of a group of microcracks does not change with pressure. However, the cumulative crack density \(\bar {\varGamma }\) of multiple groups of microcracks gradually decreases as microcracks with small aspect ratios close. To describe the squirt flow generated between microcracks due to fluid pressure gradients, the dual crack model is applied to real rock. The first step is to obtain the porosity distributions of multiple groups of microcracks with different aspect ratios:

-

1.

When a rock is in an unpressurized state, as shown in Fig. 4a, all microcracks are in the initial state. At \({P_1}\), the microcrack of the group with the smallest aspect ratio \({\alpha _1}\) is closed, as shown in Fig. 4b. Thus, when the closure pressure is \({P_1}\), the microcracks of the group with aspect ratio \({\alpha _1}\) are closed, and the fluid is ejected into the microcracks of groups 2, 3… N, which have larger aspect ratios and stiff pores. At this point, the modulus of the rock in the first, second,… Nth groups of microcracks and stiff pores can be represented by \({K^*}\) and \({G^*}\) in Eqs. (24)–(28), whereas \({K_{b}}\) and \({G_{b}}\) are the background moduli of the second, third,…Nth groups of microcracks and stiff pores, respectively, such that the microcrack density \({\varGamma _1}\) of closed group 1 can be calculated.

-

2.

When the pressure of the rock increases to \({P_2}\) (Fig. 4c) from the pressure \({P_1}\) (Fig. 4b), the second group of microcracks closes, and the fluid in these microcracks is ejected into the third, fourth… Nth groups of microcracks and stiff pores, at which time the modulus of the rock containing the second, third… Nth groups of microcracks and stiff pores can be represented by \({K^*}\) and \({G^*}\) in Eqs. (24)–(28), and the background moduli \({K_{b}}\) and \({G_{b}}\), which are the moduli of the rock containing the third, fourth… Nth groups of microcracks and stiff pores, Γ2 can be obtained as the density of the second group of microcracks that are closed under pressures of \({P_2}\) .

-

3.

When the pressure of the rock increases to \({P_n}\) from \({P_{n - 1}}\), the nth group of microcracks closes, and the fluid in these microcracks is ejected into the n, …, N groups of microcracks and stiff pores, where n = 1, 2 … N, group N is the group of microcracks with the largest aspect ratio. The modulus of the rock containing the nth,…, Nth groups of microcracks and stiff pores can be represented by \({K^*}\) and \({G^*}\) in Eqs. (24)–(28), and the background moduli \({K_{b}}\) and \({G_{b}}\), which are the moduli of the rock containing the n + 1 … N group microcracks and stiff pores, Γn can be obtained as the density of the n group of microcracks that close under pressures of \({P_n}\) .

-

4.

The density of microcracks with the largest aspect ratio of the last group N is obtained from steps 1, 2 and 3 above, and the cumulative crack density \(\bar {\varGamma }\left( {\alpha _{i}^{0}} \right)\) is obtained from the following equation:

where \(\bar {\varGamma }\left( {\alpha _{i}^{0}} \right)\) denotes the sum of the crack densities of all unclosed microcracks with aspect ratios greater than \(\alpha _{i}^{0}\), i.e., the cumulative crack densities of the unclosed cracks at \({P_i}\).

-

5.

The microcrack density in dry rocks generally tends to decrease exponentially with increasing effective pressure44. After the cumulative crack density \(\bar {\varGamma }\left( {\alpha _{i}^{0}} \right)\) is obtained, the cumulative crack density at any pressure P can be obtained via the following equation:

where \({\bar {\varGamma }^0}\) is the initial cumulative crack density and \(\hat {P}\) is a fitting parameter of the same order of magnitude as P.

After the cumulative density of microcracks is obtained, the distribution of the aspect ratios of the compliant pores must also be determined to obtain the porosity distribution. David and Zimmerman33 presented an equation for the initial minimum aspect ratio \(\alpha _{i}^{0}\) for all compliant pores that are not closed at the effective pressure P:

where \(\bar {\varGamma }\left( P \right)\) is the cumulative crack density of unclosed compliant pores at effective pressure P, \({\bar {\varGamma }^0}\) is the initial crack density, \({K_{d}}\) is the bulk modulus of the rock at effective pressure P, and \({K_{h}}\) is the bulk modulus of the rock when all microcracks are fully closed. Substituting Eq. (31) into Eq. (32), the equation reduces to

where \({K_{h}}\) is not replaced by \({K_{b}}\) here, and if \({K_{h}}\) of Eq. (33) were replaced by \({K_{b}}\), the equation would correspond to a process of changing the aspect ratio of this set of microcracks from the time they started as a minimum aspect ratio to the time that they were fully closed.

Using the above method, we can extract the crack distribution characteristics of rock from the velocity-pressure curve of dry rock. However, this crack distribution characteristic is the crack distribution characteristic of rock when the effective pressure is zero. Zimmerman32 noted that during a gradual increase in the pressure, the decrease in the aspect ratio of compliant pores of each aspect ratio in rock is the same, and the relationship between the aspect ratio of all compliant cracks and the pressure is

However, according to the conditions assumed in this work, when the pressure increases to ΔP, the first group of microcracks with an initial aspect ratio of \({\alpha _1}\) closes, so that the aspect ratio of each group of microcracks decreases by \({\alpha _1}\), and when the second group of microcracks with an initial aspect ratio of \({\alpha _2}\) closes, the aspect ratio of each group of microcracks decreases by \({\alpha _2}\) compared with the initial state; analogously, all groups of microcracks close.

Now we have the aspect ratio of each set of microcracks, \({\alpha _1}\), \({\alpha _2}\), …., \({\alpha _N}\) corresponding to the crack densities \({\bar {\varGamma }_1}={\bar {\varGamma }^0} - \bar {\varGamma }\left( {{P_1}} \right)\), \({\bar {\varGamma }_2}=\bar {\varGamma }\left( {{P_1}} \right) - \bar {\varGamma }\left( {{P_2}} \right)\), …, \({\bar {\varGamma }_N}=\bar {\varGamma }\left( {{P_{N - 1}}} \right) - \bar {\varGamma }\left( {{P_N}} \right)\). The porosity of each set of microcracks at pressure P can be expressed as

The distribution of microcrack porosity in rock can be obtained via Eq. (35).

Multiple microcrack squirt flow model

In the previous section, we obtained the porosity distribution of each group of microcracks with different aspect ratios. In this section, we propose a squirt flow model considering the flow between microcracks with different aspect ratios.

The frequency-dependent bulk modulus of the modified frame \({K_{mf}}\left( P \right)\) and shear modulus \({\mu _{mf}}\left( P \right)\) can be expressed as

where \({\phi _{c}}\left( P \right)\) is the microcrack porosity under the current effective pressure P, \(\eta\) is the shear viscosity, and \(K_{f}^{*}\left( \omega \right)\) is given by Eq. (16). \({K_{h}}\) is the high-pressure bulk modulus of the dry rock when all microcracks are closed. \({K_{g}}\) is the equivalent mineral matrix modulus, which can be calculated via the Voigt‒Reuss‒Hill averaging equation 43:

where \({f_i}\) is the volume content of each mineral component and \({M_i}\) is the bulk or shear modulus of the ith mineral component.

We start by discussing the squirt flow effect between microcracks with different aspect ratios. When the rock contains only one kind of microcracks with an aspect ratio of \({\alpha _{c}}\), the volume compression coefficient \({C_{p}}\) of the microcrack satisfies32

Based on the discussion in the previous sections, we know that when waves pass through interconnected cracks with different aspect ratios, cracks with smaller aspect ratios produce greater deformation, resulting in greater flow pressure, and fluid will squirt into cracks with larger aspect ratios. For ease of understanding, we assume that the cracks with a minimum aspect ratio \({\alpha _1}\) are the most compliant and generate greater flow pressure, and the squirt fluid enters into the cracks with the larger aspect ratios of \({\alpha _2}\), \({\alpha _3}\),…, \({\alpha _N}\) and stiff pores. In this case, the rock moduli \({K_2}\) that include the effects of compliant microcracks with aspect ratios equal to or larger than \({\alpha _2}\) and stiff pores can be used instead of \({K_{h}}\) as the background modulus; here, the squirt flow effect can be described as

where \({\phi _1}\), \({K_1}\) and \({C_1}\) are the compliant crack porosity, bulk modulus and volume compressibility coefficient, respectively.

Similarly, when a crack with an aspect ratio \({\alpha _2}\) is considered to be the most compliant crack, the fluid squirt into the larger aspect ratios \({\alpha _3}\), \({\alpha _4}\), …, \({\alpha _N}\) and stiff pores. In this case, the rock moduli \({K_3}\) including the effects of the compliant microcracks with aspect ratios equal to or larger than \({\alpha _3}\) and stiff pores can be used instead of \({K_{h}}\) as the background modulus. The squirt flow effect can be described by

By substituting Eq. (41) into Eq. (40), the following equation can be obtained

When fluid in the n group of microcracks with aspect ratio \({\alpha _n}\) starts to squirt into microcracks with larger aspect ratios or stiff pores, the squirt flow effect can be described by

Then introducing other sets of cracks with different aspect ratios via this approach, the expanded squirt flow model considering multiple sets of cracks with different aspect ratios can be obtained:

As shown in Eq. (16), \(K_{f}^{*}\left( \omega \right)\) is based on the one-dimensional fluid pressure diffusion equation. The saturated moduli \({K_{sat}}\left( {P,\omega } \right)\) and \({\mu _{sat}}\left( {P,\omega } \right)\) can be obtained via the Gassmann equation :

and

Results

Numerical simulation and validation of the analytical methods

In this section, we not only explore the distribution of fluid pressure at different frequencies in the saturation model but also introduce a method for obtaining the stiffness of the drying model through the numerical simulation mentioned in Step 1 of the previous section and compare and validate the stiffness components that vary with frequency in the saturation model with the results obtained by the analytical method.

In numerical simulations, the model consists of a fluid-saturated pore space and an elastic solid material. The momentum conservation equation is

The Lamé–Navier equation is used to describe the isotropic elastic linear solid, and the constitutive equation is written as

where \({\mathbf{\varepsilon }}\) is the strain tensor, \({\text{dev}}\left( {\mathbf{\varepsilon }} \right)\) is the partial strain related to shape change, e is the trace of the strain tensor related to volume change, I is the unit tensor, i is the imaginary unit, and \(\omega\) is the angular frequency. The bulk moduli \({K_{s}}\) and \({K_{f}}\), shear modulus \(\mu\), and shear viscosity \(\eta\) of the solid and fluid materials are shown in Table 1. The fluid is represented by the viscous compressible Navier-Stokes equation, which can be expressed by the constitutive equation:

Only the fluid is affected by frequency, and the stress and strain have complex values.

The model is a rectangular elastic solid material with the dimensions of 0.4 m \(\times\) 0.4 m \(\times\) 0.2 m, and the pore space design is shown in Fig. 1. The model can be scaled proportionally. The geometric properties of all models used in this work are shown in Table 2.

The effective stiffness tensor of dry rocks can be obtained either experimentally or by numerical simulations. In this study, the tensor components were obtained through numerical simulations of normal compression tests, shear tests, and direct mixing tests. The specific boundary setting can be found in Appendix A of Alkhimenkov et al.15, where the displacement is set to a harmonic disturbance of \(u={10^{ - 8}}{{e}^{{\text{i}}\omega t}}\) m. The obtained stress and strain data are averaged in the spatial domain. Discretizing the entire region via an unstructured mesh of tetrahedral elements, a total of 323,124 units are obtained, with the smallest unit with the size of 1.43 \(\times\) 10-3 m in the thin crack and the largest unit with the size of 32.2 \(\times\) 10-3 m in the background solid matrix. The grid size distribution is shown in Fig. 5. The boundary between the solid domain and the fluid domain is naturally coupled; that is, the displacement is described by the same variable. The model is solved using the finite element method, and the linear equation system is solved via the direct PARDISO solver45.

The results of the numerical simulation of the fluid pressure distribution at different frequencies are shown in Fig. 6. The distribution of fluid pressure at characteristic frequencies (Fig. 6c) in the dual crack model (Fig. 6a), compared with the relaxed state of low and uniform fluid pressure (Fig. 6b), shows that the fluid pressure of the compliant crack at the joint is low, the fluid pressure away from the joint is high, and the stiffness is high, corresponding to the maximum gradient of the flow pressure in the crack.

The inverse quality factor 1/Q is an important characteristic parameter for characterizing the propagation attenuation of P-waves in rocks. \({1 \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {1 {Q\left( \omega \right)}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {Q\left( \omega \right)}}={\text{Im}}\left( {M\left( \omega \right)} \right)/{\text{Re}}\left( {M\left( \omega \right)} \right)\), where \(\omega =2\pi f\) is the angular frequency (f is the frequency), \(M=K+\frac{4}{3}G\) is the complex value P-wave modulus, K is the volume modulus, and G is the shear modulus. In this study, the inverse quality factor is used to represent attenuation.

Figure 7 shows the real part (a) and 1/Q attenuation (b) of the complex component of the stiffness matrix obtained by the analytical models and simulations for the torus model, the single sphere model and the dual crack model. All models show the same shape of the attenuation curve 1/Q at low frequency. At high frequency, the slope of the large torus model surrounding the crack is \({\omega ^{ - 4/10}}\), and the slopes of the single sphere model and the dual crack model with only partial connections are similar. Generally, the characteristic frequency is related to the aspect ratio of the crack. The different characteristic lengths of the squirt flow used in this study make the aspect ratio (Eq. 18) different from that of the torus model, resulting in a large difference in the frequency corresponding to the attenuation peak. The results obtained with the analytical models used in this work are in good agreement with the numerical simulation results, indicating that the models can adequately and accurately describe the frequency-dependent stiffness and attenuation of squirt flows.

As shown in Fig. 8a, as the thickness and volume of the stiff cracks increase, the value of the real part of the normal component of the stiffness matrix of the dual crack model decreases, consistent with the intuitive expectation that larger pores should have lower stiffness. At the same time, the stiffness component changes more strongly from low frequency to high frequency. As shown in Fig. 8b, as the thickness of the stiff crack increases, the attenuation peak becomes increasingly larger, and the characteristic frequency is consistent. This shows that the volume of the stiff crack is the key parameter for determining the attenuation amplitude.

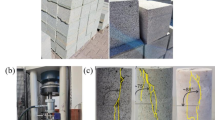

Distribution characteristics of microcracks in rock cores

We selected two sandstone samples, S133 and S2, and two dense carbonate rock samples, C1 and C246, and the pore structure parameters were inverted. Sample C1 mainly features intergranular pores and intragranular pores, whereas C2 exhibits strong heterogeneity, mainly consisting of locally developed flat microcracks. The equivalent mineral matrix modulus of mudstone sandstone sample S2 was calculated via the V-R-H method43. The mineral comprising S1 is quartz, and C1 and C2 are calcite mineral samples. The physical parameters of the rock samples are shown in Table 3.

The microcrack structure parameters of rock (microcrack aspect ratio, crack density, and porosity) are related to the selection of equivalent medium models. To examine the influence of different equivalent medium models, we compared the microcrack aspect ratio distribution, cumulative microcrack density distribution, and microcrack porosity distribution obtained using four equivalent medium models, namely the KT, MT, DEM, and SCA models, as shown in Figs. 9 and 10.

Figure 9 shows the cumulative microcrack density distributions \(\bar {\varGamma }\left( \alpha \right)\) of the four samples under effective pressures of 0, 5, 10, ..., 100 MPa, and it is observed that the cumulative crack density decreases with increasing crack aspect ratio. This is because \(\bar {\varGamma }\left( \alpha \right)\) is the sum of the crack densities of all open microcracks with crack aspect ratios greater than \(\alpha\). For larger \(\alpha\), there are fewer cracks in the rock with aspect ratios greater than \(\alpha\), resulting in a lower cumulative crack density. In addition, as shown in Fig. 9, with increasing effective pressure, the cumulative crack density gradually decreases, the \(\bar {\varGamma }\left( \alpha \right)\) curve moves to lower crack aspect ratios, and the range of the aspect ratio decreases. This is because as the pressure increases, microcracks with smaller aspect ratios in the rock close first, whereas microcracks with larger aspect ratios are gradually compressed, resulting in a decrease in the aspect ratio and a narrower distribution range of open microcracks. The four different equivalent medium theories show essentially the same trend of the calculated values of \(\bar {\varGamma }\left( \alpha \right)\) at low effective pressures, but with slight differences in the numerical values. This difference gradually decreases and then disappears with increasing effective pressure. Overall, the choice of the equivalent medium theory has a relatively small effect on the inversion results of the pore aspect ratio and cumulative crack density.

Figure 10 shows the porosity \({\phi _i}\left( \alpha \right)\) of rock microcracks under different effective pressures. As shown in Fig. 10, the variation characteristics of porosity \({\phi _i}\left( \alpha \right)\) with respect to the pore aspect ratio and effective pressure are similar to those of the cumulative crack density curve \(\bar {\varGamma }\left( \alpha \right)\). That is, as the effective pressure increases, the distribution range of the pore aspect ratio of microcracks becomes narrower, the curve shifts toward lower aspect ratios, and the inversion results of the four models gradually become more similar. It is observed that microcracks with aspect ratios of 0.2 \(\times\)10-3, 0.65 \(\times\)10-3, 0.4 \(\times\) 10-3 and 0.25 \(\times\)10-3 dominate in sandstone samples S1 and S2 and carbonate samples C1 and C2, respectively. For sandstone samples S1 and S2 and carbonate samples C1 and C2, when the effective pressure increases to 50, 50, 80, and 60 MPa, respectively, the microcracks are almost completely closed, and porosity approaches zero. Because C1 is a porous carbonate rock sample with a wider aspect ratio distribution than C2 which is a fractured carbonate rock, it is more difficult to close the microcracks for C1 and it has a higher closure pressure.

Application and validation of the multiple microcrack squirt flow model

Based on the structure of multiple microcracks in rock obtained from ultrasonic data of dried samples, a model of squirt flow that accounts for the local flow between the microcracks is proposed by applying the dual crack model.

To better understand the multiple microcrack squirt flow model, multiple sets of microcrack squirt flow models were loaded with microcracks in descending order of the aspect ratio. The P-wave velocity dispersion (a) and attenuation (b) of saturated sandstone samples S1 and S2 and tight carbonate rock samples C1 and C2 in the entire seismic-logging-ultrasonic frequency range under an effective pressure of 0 MPa are predicted, and the results are compared with experimental data (c), as shown in Figs. 11, 12, 13 and 14. As shown in Figs. 11, 12, 13 and 14a, with the addition of an increasing number of microcracks, the high-frequency limit increases, and the corresponding frequency also increases, whereas the low-frequency limit decreases, and the corresponding frequency decreases. This occurs because as the number of microcracks increases, the elastic modulus of dry rock decreases, corresponding to a lower low-frequency limit and a higher high-frequency limit. As shown in Figs. 11, 12, 13 and 14b, the peak of attenuation also shifts toward higher frequencies, and the frequency transition range widens accordingly. During the loading process of microcracks, the aspect ratio of the added microcracks increases, so that the corresponding characteristic frequency and the distribution range of the aspect ratio increase, and the frequency transition interval gradually widens. The red curves in Figs. 11, 12, 13 and 14a,b correspond to the state where all microcracks have been loaded. As shown in Figs. 11, 12, 13 and 14c, the saturation velocity predicted by the multiple microcrack squirt model is in good agreement with the ultrasonic experimental data, and the prediction error is less than 2%. In particular, at low effective pressures, the agreement is very good, and at high effective pressures, the prediction accuracy is slightly reduced. The Gurevich squirt model5 has a maximum prediction error of 8% (S2) but shows better agreement with the experimental data at high effective pressures.

Discussion

Currently, most analysis models that seek to quantitatively describe the dispersion and attenuation of earthquakes, logging, and laboratory ultrasound are based on classic geometric structures. Torus pores, which are stiff pores, are interconnected with coin-shaped cracks which are compliant cracks5,9,17. The stiffness of the model corresponding to this geometric configuration is mainly controlled by the torus pore; that is, the thickness of the cracks does not affect the stiffness, which is clearly different from the actual situation in real rocks17. In real rock, stiffness is the sum of the contributions of three different parts of the rock, namely the rock matrix, stiff pores or cracks, and compliant pores or cracks. A greater content of pores increases compliance of the rock, and cracks also affect the rock stiffness17. In addition, these models are based on isotropic media5,47; however, cracks in rock exhibit anisotropy, with different crack directions, which must be considered when constructing a squirt flow model suitable for fractured rock.

For fluid flow in the pore space, the pore and cracks are only partially connected, and the connection area is small; for example, in the case of the dual crack model, the characteristic length of the squirt flow is approximately equal to the diameter of the crack. In the classic model mentioned above, the characteristic length of the squirt flow is closer to the radius of the crack. The characteristic length of the squirt flow refers to the maximum distance at which the fluid in the crack is squirted into the pore, that is, the length at which the fluid pressure gradient is at its maximum. Its characteristic frequency also varies according to18:

In the stiff torus pore model, the fluid in the crack flows radially toward the surrounding torus pore, whereas in the dual crack squirt flow model constructed in this study, the fluid in the compliant crack flows approximately linearly toward the smaller connection with the stiff crack, which closer to a one-dimensional flow. Attenuation is caused only by the fluid in the compliant cracks, whereas stiff cracks play a role in fluid storage. When the stiff crack is large enough, the flow pressure at the connection is zero. When the stiff crack is small, the flow pressure at the connection is not zero, and the term \({\left[ {Z_{n}^{{ap}}} \right]^{fth}}\) must be added to Eq. (13).

The application of the dual crack squirt flow model in real rock can classify the pore space as either compliant cracks or stiff cracks. The characteristic length of the squirt flow is approximately the same as the diameter of the compliant crack, and the one-dimensional fluid pressure diffusion formula is adopted. It can also be applied by constructing a more complex dual crack space, where the compliant crack is connected with one or more stiff cracks, and the characteristic length of the complex dual crack model is the average length of the characteristic length of the compliant cracks18. Multiple pore structures are obtained via the inversion method. The dual crack model can also be applied to the squirt flow effect of each group of cracks to obtain a squirt flow model that is closer to the pore structure of rock. This is exactly the approach used in this paper. Unlike the previous multiple pore squirt flow models48,49, in the dual crack model proposed in this paper, the value of the characteristic length is approximately equal to the diameter of the compliant crack (Eq. 18) rather than the radius, and the fluid pressure diffusion is one-dimensional (Eq. 16) rather than radial.

Generally, predictive models in rock physics rely on the quantitative description of certain physical concepts on the basis of specific assumptions. This study follows five steps to ensure that the proposed analytical model accurately describes physical concepts and can be extrapolated to real rocks for effective application, as shown in Fig. 15. Typically, only Steps 1 and 4 are involved in the “validation” step of the analytical model, and deviations from laboratory results may sometimes occur because of the lack of consideration of other key factors. With the development of computational techniques, three-dimensional numerical solutions can increasingly accurately describe physical concepts (Step 2), and their results should be mutually verified with the results of the analytical model to ensure that the analytical model can accurately describe the physical properties in specific geometries and evaluate the influence of key parameters for the analytical model (Step 3). The analytical model that can accurately describe simple geometric and physical concepts, verified through the above steps, is then extrapolated to real rocks by constructing the relationship between simple geometry and real pore space (Step 4) and verified again with laboratory data (Step 5) to ensure that the target practical problem can be accurately solved.

Conclusion

We present an analytical model of dual crack squirt flow, analyze the stiffness attenuation and dispersion of the model, and propose an application to real rocks by constructing simple geometries with respect to real pore space. The geometrical configuration of the analytical model consists of dual cracks with the same diameter but different thicknesses, accounts for the effect of the dual crack connection on the elastic modulus, introduces a more appropriate one-dimensional fluid pressure dispersion equation, provides a better approximation of the stiffness relaxation of the compliant cracks, and modifies the expression for the aspect ratio controlling the characteristic frequency. The results obtained by dual crack analytical model are highly consistent with the results of accurate 3D numerical simulations over the entire frequency band. For real rock, we extracted the aspect ratio and porosity distribution of microcracks from ultrasonic velocity-pressure curves. Considering the squirt flow between the microcracks that approximates the dual crack model, we apply the dual crack squirt flow analytical model to real rocks and obtain a method that accurately predicts the velocity dispersion and attenuation in rocks with multiple microcracks. Comparison to the simulation results shows that the dual crack squirt flow analytical model provides an adequate description of the physical properties of the geometric configurations, and the predictions extrapolated to real rocks are in good agreement with the results of ultrasonic experiments. This study adequately demonstrates the process of constructing and applying a quantitative and qualitative squirt flow model that can be used to predict velocity dispersion and attenuation in real multi-microcrack rocks. The method can also be used to predict velocity dispersion and attenuation in saturated rocks with other types of pores.

Data availability

The data and code that support the findings of this study are available in GitHub at https://github.com/YvetChen/An-accurate-analytical-model-and-application-method.git. Any additional information required to reanalysed the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

Müller, T. M., Gurevich, B. & Lebedev, M. Seismic wave Attenuation and dispersion resulting from wave-induced flow in porous rocks—A review. Geop. 75, 75A147–175A164. https://doi.org/10.1190/1.3463417 (2010).

Mavko, G. & Nur, A. Melt squirt in the asthenosphere. J. Phys. Res. 80, 1444–1448. https://doi.org/10.1029/JB080i011p01444 (1975).

O’Connell, R. J. & Budiansky, B. Viscoelastic properties of fluid-saturated cracked solids. J. Geophys. Res. (1896–1977). 82, 5719–5735. https://doi.org/10.1029/JB082i036p05719 (1977).

Mavko, G. & Jizba, D. Estimating grain-scale fluid effects on velocity dispersion in rocks. Geop. 56, 1940–1949. https://doi.org/10.1190/1.1443005 (1991).

Gurevich, B., Makarynska, D., de Paula, O. B. & Pervukhina, M. A simple model for squirt-flow dispersion and Attenuation in fluid-saturated granular rocks. Geop. 75, N109–N120. https://doi.org/10.1190/1.3509782 (2010).

Wu, C. F., Ba, J., Carcione, J. M., Müller, T. M. & Zhang, L. A patchy-saturated rock physics model for tight sandstone based on microscopic pore structures. Appl. Geophys. 19, 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11770-022-0938-2 (2022).

Ba, J., Wei, Y., Carcione, J. M., Adam, L. & Tang, G. Stress and frequency dependence of wave velocities in saturated rocks based on acoustoelasticity with squirt-flow dissipation. GeoJI. 236, 1753–1763 (2024).

Wei, Y., Ba, J. & Carcione, J. M. Stress effects on wave velocities of rocks: Contribution of crack closure, squirt flow and acoustoelasticity. JGRB. 127, e2022JB025253 (2022).

Murphy, W. F., Winkler, K. W. & Kleinberg, R. L. Acoustic relaxation in sedimentary rocks; dependence on grain contacts and fluid saturation. Geop. 51, 757–766 (1986).

Dvorkin, J., Nolen-Hoeksema, R. C. & Nur, A. The squirt-flow mechanism; macroscopic description. Geop. 59, 428–438. https://doi.org/10.1190/1.1443605 (1994).

Chapman, M., Zatsepin, S. V. & Crampin, S. Derivation of a microstructural poroelastic model. GeoJI. 151, 427–451. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-246X.2002.01769.x (2002).

Chapman, M. Frequency-dependent anisotropy due to meso‐scale fractures in the presence of equant porosity. GeopP. 51, 369–379 (2003).

Jakobsen, M. & Chapman, M. Unified theory of global flow and squirt flow in cracked porous media. Geop. 74, WA65–WA76. https://doi.org/10.1190/1.3078404 (2009).

Quintal, B., Caspari, E., Holliger, K. & Steeb, H. Numerically quantifying energy loss caused by squirt flow. GeopP. 67, 2196–2212. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2478.12832 (2019).

Alkhimenkov, Y. et al. Frequency-dependent Attenuation and dispersion caused by squirt flow: Three-dimensional numerical study. Geop. 85, MR129–MR145. https://doi.org/10.1190/geo2019-0519.1 (2020).

Alkhimenkov, Y. & Quintal, B. An accurate analytical model for squirt flow in anisotropic porous rocks part 2: complex geometry. Geop. 87, MR291–MR302. https://doi.org/10.1190/geo2022-0143.1 (2022).

Alkhimenkov, Y. & Quintal, B. An accurate analytical model for squirt flow in anisotropic porous rocks - Part 1: classical geometry. Geop. 87, MR85–MR103. https://doi.org/10.1190/geo2021-0229.1 (2022).

Alkhimenkov, Y. & Quintal, B. A simple and accurate model for Attenuation and dispersion caused by squirt flow in isotropic porous rocks. Geop. 89, MR1–MR10. https://doi.org/10.1190/geo2023-0049.1 (2024).

Kuster, G. T. & Toksöz, M. N. Velocity and Attenuation of seismic waves in two-phase media: part I. Theoretical formulations. Geop. 39, 587–606. https://doi.org/10.1190/1.1440450 (1974).

Mori, T. & Tanaka, K. Average stress in matrix and average elastic energy of materials with misfitting inclusions. Acta Metall. 21, 571–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-6160(73)90064-3 (1973).

Benveniste, Y. A new approach to the application of Mori-Tanaka’s theory in composite materials. Mech. Mater. 6, 147–157 (1987).

Wu, T. T. The effect of inclusion shape on the elastic moduli of a two-phase material. IJSS 2, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-7683(66)90002-3 (1966).

Budiansky, B. On the elastic moduli of some heterogeneous materials. J. Mech. Phys. Solids. 13, 223–227 (1965).

Berryman, J. G. Long-wavelength propagation in composite elastic media I. Spherical inclusions. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 68, 1809–1819 (1980).

Berryman, J. G. & Wang, H. F. The elastic coefficients of double-porosity models for fluid transport in jointed rock. JGRB. 100, 24611–24627 (1995).

Norris, A. N. A differential scheme for the effective moduli of composites. Mech. Mater. 4, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-6636(85)90002-X (1985).

Zimmerman, R. In Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstracts 339–343 (Elsevier).

Berryman, J. G., Pride, S. R. & Wang, H. F. A differential scheme for elastic properties of rocks with dry or saturated cracks. GeoJI. 151, 597–611 (2002).

Kumar, M. & Han, D. In 2005 SEG Annual Meeting.

de Paula, O. B., Pervukhina, M., Makarynska, D. & Gurevich, B. Modeling squirt dispersion and attenuation in fluid-saturated rocks using pressure dependency of dry ultrasonic velocities. Geop. 77, WA157–WA168. https://doi.org/10.1190/geo2011-0253.1 (2012).

Cheng, C. H. & Toksöz, M. N. Inversion of seismic velocities for the pore aspect ratio spectrum of a rock. JGRB. 84, 7533–7543. https://doi.org/10.1029/JB084iB13p07533 (1979).

Zimmerman, R. W. Compressibility of sandstones. (1990).

David, E. C. & Zimmerman, R. W. Pore structure model for elastic wave velocities in fluid-saturated sandstones. JGRB. 117 https://doi.org/10.1029/2012JB009195 (2012).

Wu, C. et al. A squirt-flow theory to model wave anelasticity in rocks containing compliant microfractures. PEPI. 301, 106450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pepi.2020.106450 (2020).

Gassmann, F. Uber die elastizitat Poroser medien. VNG. 96, 1–23 (1951).

Kachanov, M. & Sevostianov, I. Micromechanics of Materials, with Applications, vol. 249 (Springer, 2018).

Schoenberg, M. & Douma, J. Elastic wave propagation in media with parallel fractures and aligned cracks1. GeopP. 36, 571–590 (1988).

Schoenberg, M. & Helbig, K. Orthorhombic media: modeling elastic wave behavior in a vertically fractured Earth. Geop. 62, 1954–1974 (1997).

Tsai, H. C. & Lee, C. C. Compressive stiffness of elastic layers bonded between rigid plates. IJSS. 35, 3053–3069 (1998).

Hashin, Z. Complex moduli of viscoelastic composites—I. General theory and application to particulate composites. IJSS. 6, 539–552 (1970).

Berryman, J. G. Mixture theories for rock properties. Rock. Phys. Phase Relat. Handb. Phys. Constants. 3, 205–228. https://doi.org/10.1029/RF003p0205 (1995).

David, E. & Zimmerman, R. W. Elastic moduli of solids containing spheroidal pores. IJES. 49, 544–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijengsci.2011.02.001 (2011).

Mavko, G., Mukerji, T. & Dvorkin, J. The Rock Physics Handbook (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

Shapiro, S. A. Elastic piezosensitivity of porous and fractured rocks. Geop. 68, 482–486. https://doi.org/10.1190/1.1567215 (2003).

Schenk, O. & Gärtner, K. Solving unsymmetric sparse systems of linear equations with PARDISO. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 20, 475–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2003.07.011 (2004).

Ouyang, F. et al. Inversion of pore aspect ratio distribution based on effective medium theories. ChJG. 64, 1016–1033. https://doi.org/10.6038/cjg2021O0348 (2021).

Collet, O. & Gurevich, B. Frequency dependence of anisotropy in fluid saturated rocks—Part I: aligned cracks case. GeopP. 64, 1067–1084. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2478.12384 (2016).

Ouyang, F. et al. Modeling velocity dispersion and attenuation using pore structure characteristics of rock. ChJG. 64, 1034–1047. https://doi.org/10.6038/cjg2021O0355 (2021).

Deng, J., Zhou, H., Wang, H., Zhao, J. & Wang, S. The influence of pore structure in reservoir sandstone on dispersion properties of elastic waves. ChJG. 58, 3389–3400. https://doi.org/10.6038/cjg20150931 (2015).

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42141009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.C.: Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing. P.D.: Writing-review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. Y.Z.: Formal analysis, data curation, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing, visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Y., Dong, P. & Zhang, Y. An accurate analytical model and application method for squirt flow in anisotropic fractured rocks. Sci Rep 15, 17496 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01439-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01439-8