Abstract

Female infertility represents a significant reproductive health issue that critically affects global fertility rates. In this study, we utilized the most recent data from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study 2021. Initially, we assessed the global burden by the number of female infertility prevalence and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), along with the age-standardized rate (ASR) per 100,000 individuals, stratified by age, sociodemographic index (SDI), nationality, and region. Furthermore, linear regression models were employed to examine the temporal trends of disease burden from 1990 to 2021. Cluster analysis facilitated the evaluation of disease burden change patterns across different GBD regions. Lastly, the autoregressive composite moving average model was applied to forecast future disease burdens. In 2021, the global prevalence of female infertility was estimated at 110,089,459, contributing to 6,210,145 DALYs, there was an observed increase of 84.44% in prevalence and 84.43% in DALYs since 1990. The highest burden occurred among individuals aged 35–39, with the most rapid increase observed in the 30–34 age group. The burden of female infertility displayed considerable variability across GBD regions and countries, with areas of high-medium SDI facing elevated risks. Projections indicate a continuing rise in the ASR of prevalence and DALYs for female infertility over the next 2 decades. The global burden of female infertility has intensified from 1990 to 2021, with notable disparities across different SDI regions and countries. Women aged 35–39 face the highest risk, and there is a trend toward earlier onset of infertility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Female infertility represents a significant public health concern globally, defined as the inability to conceive after more than 12 months of regular unprotected intercourse without contraception through WHO1,2, which is different from the definition of GBD2021. This condition is categorized into primary and secondary infertility. In the United States, an estimated 7–15.5% of women of childbearing age are afflicted with infertility3,4. And the economic cost of ART treatment for infertile women is high, for example: The cost (in 2006 United States dollars) of a standard IVF cycle ranged from $12,513 in the United States to $3956 in Japan5. Worldwide, infertility impacts millions of families, affecting approximately one in seven couples in developed countries and one in four in developing countries6. In China, over 50 million women of childbearing age suffer from infertility, constituting 15% of this demographic7. In many developing countries, Infertility is common and often linked to negative psychosocial effects. In Morocco, even with increasing knowledge about the causes and treatments of infertility, women continue to face social stigma and marital issues, such as divorce or polygamy, due to infertility being associated with them8.

The predominant cause of female infertility is fallopian tube obstruction, while secondary causes include ovulatory disorders related to diminished ovarian reserve, endocrine disruptions, and delayed childbearing. Genetic factors also contribute, with 5–10% of affected women displaying chromosomal anomalies, gene mutations, or polymorphisms9. Additionally, environmental influences, endocrine dysfunctions, and hormonal imbalances explain a considerable portion of infertility cases. Emerging research suggests that infertile women may face an elevated risk of gynecological cancers10. Moreover, conditions such as endometriosis are linked with higher incidences of melanoma, asthma, autoimmune disorders, allergic diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and ovarian cancer11. The multifaceted impact of female infertility underscores the necessity for a comprehensive understanding of its complexities and implications.

Current epidemiological research on female infertility is notably sparse. One pivotal study analyzed data from 277 demographic and reproductive health surveys, uncovering variations in the prevalence of primary and secondary infertility across 190 countries and territories from 1990 to 201012. Notably, regions such as North Africa and the Middle East, particularly Morocco and Yemen, exhibited high rates of primary infertility but low rates of secondary infertility. Conversely, Central and Eastern Europe along with Central Asia showed higher prevalence of secondary infertility and lower incidence of primary infertility. A separate analysis on the disease burden associated with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) revealed a significant increase in infertility cases linked to PCOS among women aged 15 to 49 years—from 6 million cases in 1990 to 12.13 million in 201913. Research on endometriosis-related infertility indicated a slight decrease in the global burden from 1990 to 2019, though substantial regional, age-related, temporal, and cohort-based disparities persist14.

Differences in the burden of female infertility among countries may stem from several factors, including widespread preconception testing, complexity in diagnostic processes, the adoption of assisted reproductive technologies, and disparities in medical resource distribution.

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study serves as a crucial resource for understanding the epidemiological status of various diseases, encompassing data on prevalence, incidence, mortality, and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). We derived specific data (prevalence and DALYs) on female infertility from the most recent 2021 GBD study. This study also offers a detailed breakdown of the prevalence, and DALYs of female infertility by age, geographic region, and the sociodemographic index (SDI), emphasizing SDI distribution and the temporal patterns and trends in disease burden. Projecting the disease burden from 2020 to 2050, this analysis is aimed at aiding clinicians, epidemiologists, and health policymakers in devising and evaluating effective public health strategies to mitigate the substantial disease burden, offering considerable benefit and value.

Results

The disease burden attributable to female infertility in 2021

In 2021, the global prevalence of female infertility was estimated at 110,089,459 cases, with a 95% uncertainty interval (UI) of 58,608,815–195,025,585. The ASPR (age-standardized prevalence rate, ASPR) was 1367.36 per 100,000 population. DALYs (Disability-adjusted life years, DALYs) associated with female infertility totaled 601,134, with an age-standardized rate of 7.48 per 100,000 population (95% UI 2.65–18.23) (Tables 1 and 2).

The ASPR and DALYs were highest in the 35–39 age group, showing a peak before declining. Both the number of prevalence cases and DALYs followed similar age-related patterns as the age-standardized DALYs rates (Fig. S1). In 2021, the prevalence and DALYs in the 35–39 age group were 1.14 and 1.13 times higher, respectively, than those in the 30–34 age group (Fig. S1). The corresponding age-standardized rates were 1.23-fold and 1.21-fold higher, respectively (Fig. S1, Tables 1 and 2).

At the regional level, based on the sociodemographic index (SDI), the Middle SDI region recorded the highest numbers of female infertility cases at 39,038,802 and DALYs at 211,708 in 2021. However, the highest corresponding ASRs (age-standardized rate) were observed in the high-middle SDI region (Fig. 1, Tables 1 and 2). The relationship between SDI levels and disease burden remained consistent across countries and regions. As illustrated in Fig. S2, the relationship between the ASPR and sociodemographic index (SDI) manifests as a “wave”. Age-Standardized DALYs Rate and SDI have the same relationship. In different territories and countries where the SDI is under 0.50, the trend is predominantly stable and tends to decrease slightly. For SDI levels between 0.50 and 0.75, the trend shows mild fluctuations, whereas regions with an SDI above 0.75 experience a rapid decline in both ASPR and age-standardized DALY’s rate across territories and countries.

Among the GBD regions, Asia reported the highest prevalence (80,708,741, 95% UI 44,013,820–140,273,972) and DALYs (440,253, 95% UI 160,445–1,076,577), while Australasia had the lowest (prevalence: 23,946, 95% UI 5,824–97,727; DALYs: 135, 95% UI 22–593). For age-standardized rates, East Asia showed the highest prevalence (1979.77 per 100,000, 95% UI 1020.52–3458.07) and DALYs (10.4 per 100,000, 95% UI 3.56–26.14), with Australasia at the opposite end (prevalence: 76.86 per 100,000, 95% UI 18.74–304.96; DALYs: 0.44 per 100,000, 95% UI 0.07–1.86) (Fig. S3).

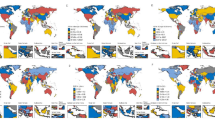

The Central African Republic exhibited the highest age-standardized prevalence of female infertility in 2021 at 3016.48 per 100,000 (95% UI 1877.54–4852.36), followed by Gabon, Djibouti, Comoros, Mozambique, and Eritrea. Similarly, the highest age-standardized DALYs were reported in the Central African Republic (16.48 per 100,000, 95% UI 6.06–37.78), with Gabon and Djibouti closely following. Australia displayed the lowest ASRs for prevalence cases and DALYs, succeeded by Colombia and New Zealand. In absolute terms, China and India observed the highest numbers of cases, with 29,317,000 (95% UI 14,569,167–52,098,692) and 29,075,289 (95% UI 16,070,794–49,483,699) respectively, followed by Indonesia and Pakistan. The smallest nations, such as Tokelau and Niue, reported the lowest counts, with zero DALYs recorded in both, followed by the Cook Islands, Greenland, and Monaco (Fig. S4).

Temporal trends in the burden of female infertility disease from 1990 to 2021

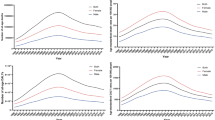

Over the 31-year period, the global disease burden showed an upward trend in female infertility patients. The prevalence cases surged from 59,690,000 in 1990 to 110,089,459 in 2021, marking an increase of 84.44%. The corresponding ASPR experienced a 22.27% rise. A similar trend was observed in the disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), with an 84.43% increase in the number of DALYs cases and a 23.03% rise in the age-standardized DALY rate (Fig. 2, Tables 1 and 2).

Examining age-specific data, among women aged 35–39, the prevalence of infertility rose from 17,089,875 in 1990 to 30,599,403 in 2021—an increase of 79.05%. The corresponding age-standardized rate similarly increased by 12.45%. In the 30–34 age group, the number of infertility cases increased from 13,279,984 in 1990 to 26,866,483 in 2021, a significant rise of 102.31%, with the corresponding age-standardized rate also showing an increase of 28.99%. These data indicate that while the heaviest disease burden remains concentrated in women aged 35–39, the number of infertility cases in women aged 30–34 is rising rapidly (Fig. 3).

Regionally, different trends were observed across various sociodemographic index (SDI) levels. Except for the high SDI regions, which showed a slow increase followed by a decreasing trend, the ASPR and the age-standardized DALYs rate in other SDI regions exhibited an overall upward trend. Notably, the ASR in the low and low-middle SDI regions initially displayed a decrease, followed by a sharp increase starting around 2010. For the prevalence cases, the low-medium SDI area initially increased, then decreased, and subsequently experienced a rapid rise starting in 2010. Conversely, in China, the number of cases and DALYs continuously increased. Meanwhile, the prevalence and DALYs in high and high-middle SDI regions remained stable (Fig. S5, Tables 1 and 2).

The burden of female infertility displays considerable variability across GBD regions. Hierarchical cluster analysis was conducted to identify regions with similar patterns of change in disease burden. According to Fig. 4, Andean Latin America exhibited a significant increase in both ASPR and age-standardized DALYs rate, whereas regions like Oceania, Eastern Sub-Saharan Africa, Southern Sub-Saharan Africa, and Southern Africa showed significant decreases, alongside regions with minimal health systems.

Among the 204 evaluated countries, from 1990 to 2021, the changes in the number of prevalence cases and DALYs followed similar patterns, with Peru experiencing the most significant increases in both metrics. Conversely, Armenia witnessed substantial declines (prevalence: − 76.36%; DALYs: − 76.57%), followed by Malawi, Albania, and Rugia, which also saw decreases in both case numbers and DALYs (Fig. 5C,D).

Changes in prevalence and DALYs attributable to female infertility across countries and territories from 1990 to 2021, along with the EAPC for the corresponding ASR. The map was generated utilizing R programming software (version 4.2.2), incorporating the “dplyr” package, as well as the “maps” “ggplot2” and “ggmap” packages. DALYs disability-adjusted life years, EAPC estimated annual percentage change, ASR age-standardized rate.

Regarding ASR, Ecuador registered the largest increase in ASPR and age-standardized DALYs rate burden over the period from 1990 to 2021, with an Estimated Annual Percent Change (EAPC) in prevalence of 9.32, 95% confidence interval (CI) from 7.26 to 11.41; and DALYs EAPC of 9.13, 95% CI from 7.12 to 11.18. This trend was followed by Peru and Bolivia (Plurinational State). The most significant decrease was observed in Malawi (number of cases: EAPC = − 6.06, 95% CI from − 6.53 to − 5.6; DALYs: EAPC = − 6.04, 95% CI from − 6.50 to − 5.57), followed by Pakistan and Uganda (Fig. 5A,B).

Factors influencing EAPC and predicted results from 2022 to 2050

An analysis was conducted to assess the relationship between EAPC and age-standardized rates (ASR), EAPC and Human Development Index (HDI) in 2021 (Fig. 6). The 2021 ASR for female infertility serves as a baseline measure of the disease reservoir, while the 2021 HDI acts as a surrogate indicator of healthcare availability at the country level. We observed a correlation between EAPC and ASR; at relatively low ASR levels, a negative association emerged between EAPC and ASR in the number of affected individuals (ASPR: ρ = − 0.007, p = 0.92) and a positive correlation with ASR in DALY (ρ = 0.004, p = 0.95), although these correlations were not statistically significant (Fig. 6A). Conversely, a statistically significant positive association was found between EAPC and HDI (ASPR: ρ = 0.26, p < 0.01; Age-Standardized DALYs rates: ρ = 0.26, p < 0.01) (Fig. 6B), indicating that in countries with high HDI, the incidence of female infertility increased in 2021 but showed a slowing trend when HDI exceeded 0.8.

Projections based on the autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model suggest that from 2022 to 2050, the global prevalence of female infertility is expected to gradually decline. However, the corresponding ASR is projected to continue rising. Similarly, DALYs are anticipated to slowly decrease during the period, yet the corresponding ASR is expected to persistently increase (Fig. S6).

Discussion

Infertility represents a significant global health issue, affecting over 9% of women of childbearing age worldwide. In 2021, female infertility contributed to a substantial disease burden, with notable variations across different ages, sociodemographic index (SDI) regions, territories and countries. The World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes infertility as a global public health concern with profound implications for individuals and societies15. To our knowledge, this study is the first to comprehensively assess and quantify the burden of female infertility across 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2021, also projecting future disease burden trends. This research aims to enhance understanding of the current and future dynamics of female infertility.

Few studies have provided a global perspective, utilizing data from the GBD 2017 study, Sun et al. explored the global prevalence of infertility and its DALYs from 1990 to 2017, revealing an increasing global burden of infertility disease, with a notably higher prevalence among women than men16. However, these analyses lacked depth in trend projection and further exploration. Leveraging data from GBD 2021, our study offers a comprehensive assessment of the global burden of female infertility. We found that in 2021, the number of prevalence female infertility cases predominantly concentrated in the medium SDI region, with the largest numbers reported in Asia. When examining ASPR and age-standardized DALYs rate, these were primarily found in the medium-high SDI region, with the East Asian region bearing the heaviest burden. This distribution may be attributed to factors such as demographics, lifestyle, dietary patterns, environmental exposures, and enhanced access to healthcare. In conjunction with previous scholarly estimates, our findings underscore that female infertility imposes a significant disease burden.

From 1990 to 2021, we noted a marked increase in the global number of female infertility prevalence, along with rises in disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and their corresponding ASRs. Female age remains a crucial determinant of natural conception and the success of treatment-related conceptions, with fertility notably declining with advancing age, particularly after 35 years17,18,19.

Upon analyzing the global burden of female infertility across all age groups, it becomes apparent that the highest concentration of cases is within the 35–39 age group. However, the most significant increases were observed in the 30–34 and 25–29 age groups, both in terms of prevalence and DALYs, as well as their corresponding ASRs. For instance, the prevalence of infertility in the 30–34 age group rose by 103.68%, with the ASR increasing by 29.91%. These changes may be attributed to factors such as delayed childbearing, urbanization, and increased emissions from industry and vehicles20, as well as advancements in infertility detection and diagnostic methods.

This trend aligns with current understandings of women’s fertility levels. Based on a survey involving 7172 women, researchers have found that women over the age of 35 are twice as likely to suffer from unexplained infertility compared to younger women21. Additionally, studies indicate a significant increase in chromosomal degeneration and aneuploidy in infertile patients over the age of 3522,23. It has also been documented that older eggs exhibit considerably greater mitochondrial damage, and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations in ovarian tissue significantly increase after the age of 4524,25. Given these findings, proactive measures and policies are essential for the diagnosis and treatment of female infertility, aiming to reduce the associated disease burden. Enhanced awareness and improved healthcare interventions could play pivotal roles in addressing this growing challenge.

Our regional analysis over the period from 1990 to 2021 reveals a slow increase followed by a decreasing trend in the number of female infertility prevalence, disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), and their corresponding age-standardized rates (ASR) in high sociodemographic index (SDI) areas. Further regression adaptation analysis indicated a nonlinear relationship between SDI and the prevalence of female infertility, DALYs, and corresponding ASR. Notably, a negative correlation emerged when SDI was greater than 0.75, suggesting that higher SDI values are associated with decreased trends in the prevalence and burden of female infertility. This finding aligns with the association analysis of Estimated Annual Percent Change (EAPC) and Human Development Index (HDI) in female infertility for the year 2021, where EAPC demonstrated a decreasing trend with HDI values over 0.8.

SDI and HDI are critical indicators for assessing the impact of socio-economic development on health and disease burden. Regions with high SDI and HDI typically exhibit superior health, economic, and social development, potentially correlating with lower disease burdens and higher quality of life26. This association likely reflects advantages such as better medical facilities, more equitable access to fertility treatments, higher socio-economic conditions, and enhanced overall health, well-being, and advocacy in high SDI regions27. These factors contribute to fewer reported fertility issues.

Significant regional and country-specific disparities in the burden of female infertility were noted. For instance, between 1990 and 2021, the number of female infertility prevalence, DALYs, and corresponding ASR significantly increased in Latin American countries such as Peru and Ecuador. Conversely, a notable decrease in the corresponding ASR was observed in Armenia, likely due to varying environmental conditions, cultural factors, preventive healthcare programs, and economic development levels. For example, data from the Peruvian Institute of Statistics indicate that the interval between pregnancies among Peruvian women has lengthened, with an average gap of 4 years in 200928. This extended interval may increase the age at second pregnancy, consequently elevating infertility rates.

Overall, while female infertility remains a significant public health issue in developed countries, its impact is more pronounced in developing regions where rapid population growth and widespread industrialization contribute to environmental and noise pollution, posing serious health threats29. We hypothesize that the trajectory of industrialized nations, marked by accelerated economic growth, may be associated with a postponement in reproductive age, particularly beyond 35 years in women, leading to an increased incidence of reported infertility. Furthermore, environmental exposures prevalent during industrialization may contribute to this phenomenon through epigenetic mechanisms that adversely impact fertility30. This observation is corroborated by the presence of the highest disease burdens in this study occurring in areas with medium and medium-high SDI.

To 2050, the projected results indicate a diverging trend in the disease burden of female infertility from 2022 onwards: while the number of affected individuals is expected to decrease, and the number of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) is anticipated to follow a downward trend, the corresponding age-standardized rate (ASR) is projected to exhibit a continuous upward trend. These opposing trends can be attributed to several interrelated factors. First, the global population continues to age, and a significant increase in the proportion of women over 30 within the childbearing population may elevate the risk of infertility. This structural aging is likely to result in an upward trend in the ASPR, despite an actual decline in the number of affected individuals due to overall population decrease. Second, the impact of lifestyle and environmental risk factors such as delayed childbearing age, occupational stress, and environmental pollution is expected to heighten the relative risk of infertility among women of childbearing age. This increase could drive up the ASPR. Third, as diagnostic capabilities improve and awareness of fertility issues heightens, more cases of infertility are likely to be diagnosed. This could lead to an increase in the age-standardized prevalence, even in regions experiencing population declines. In summary, the contrasting trends in the actual number of people with infertility and the ASR are likely a reflection of demographic shifts, escalating high-risk behaviors, and socioeconomic developments expected in the coming years.

Socioeconomic development plays a pivotal role in comprehending fertility trends. The demographic transition model posits that societies transition from high to low birth and death rates as they undergo modernization. Enhanced female education is frequently associated with delayed marriage. Empirical evidence suggests that educated women are more inclined to utilize contraception, thereby contributing to reduced fertility rates31. High-risk fertility behaviors are more prevalent in low-income countries, often linked to unmet family planning needs and child marriage. For example, research conducted in East Africa indicates that such behaviors are correlated with child stunting and anemia, highlighting their health implications32. In the short term, these behaviors may lead to elevated fertility rates, but they can also increase child mortality, thereby influencing net population growth. Additionally, other high-risk activities, such as smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, and drug abuse, may result in infertility. The American Society for Reproductive Medicine, for instance, emphasizes take the adoption of a preventive approach to infertility by discouraging tobacco use and minimizing exposure to cigarette smoke both men and women33. These relationships are intricately interconnected. Socioeconomic development has the potential to mitigate high-risk behaviors and reduce fertility rates, thereby influencing demographic structural changes. For example, reduced fertility rates contribute to population aging, which can decelerate economic growth and potentially reverse socioeconomic advancements. Conversely, in less developed regions, persistent high-risk behaviors may maintain elevated fertility rates, often accompanied by substantial health challenges.

Consequently, female infertility is anticipated to persist as a substantial public health challenge in the future. A reduction in absolute numbers does not inherently signify a decrease in the disease burden, as a thorough evaluation of various contributing factors is essential. It is imperative to prioritize early screening and preventive measures for women experiencing infertility, in conjunction with interventions targeting lifestyle modifications and psychosocial support. Furthermore, advancing research into precision medicine and assisted reproductive technologies (ART) remains crucial.

Strength and limitations

Compared to GBD 2019, GBD 2021 incorporated 43 additional data sources for the estimation of infertility impairment34. Thus, GBD studies provide robust estimates of disease burden. While previous research has estimated the burden of female infertility, most such studies were confined to single regions or countries35 or focused solely on specific factors related to female infertility14.

This study is subject to certain limitations stemming from its reliance on the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) database data. A significant challenge is the absence of detailed data from smaller administrative divisions such as counties, provinces, and states36. While the GBD database encompasses numerous countries and regions worldwide, the accuracy and completeness of the data can vary substantially, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where data may be less detailed or more susceptible to bias. Additionally, the availability of raw data within this database presents another considerable limitation37,38. Although burden of disease data were estimated using standardized Bayesian regression tools, the limited data scope introduces uncertainties, notably the global outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic may further complicate our results. Lastly, the GBD database provides population-level data, which does not include detailed personal patient information, thus limiting the depth of analysis possible regarding the epidemiological characteristics of specific subtypes or patient populations of female infertility.

Conclusion

Overall, female infertility imposes a significant disease burden and critically impacts global fertility, particularly in regions with high-medium levels of economic development. This study reaffirms the significant influence of age on female fertility, highlighting an emerging trend where the onset of female infertility is occurring at progressively younger ages. We also observe that while the absolute number of cases may decline over the next 25 years, the ASPR and age-standardized DALYs are projected to continue showing an upward trend. This underscores that female infertility remains a pressing public health issue that demands sustained research attention. Our findings should guide policymakers in prioritizing women’s infertility healthcare and underscore the necessity for effective prevention and management interventions to mitigate the escalating burden of infertility. However, further research is needed to explore the risk factors for female infertility and prevalence trend to devise and implement effective strategies to reduce this disease’s burden.

Methods

Overview

Data specific to female infertility, including prevalence, disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), and corresponding age-standardized rates, were obtained from the Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx) website (https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/). The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2021 study represents the most extensive and scientifically rigorous effort to assess epidemiological burdens globally, encompassing 371 diseases and injuries along with 84 risk factors. Counts and age-standardized rates were calculated globally, for seven super-regions, 21 regions, 204 countries and territories (including 21 countries with subnational locations), and 811 subnational locations, from 1990 to 202134. These countries and territories were further segmented into five groups based on the sociodemographic index (SDI)39. The data sources for the 2021 GBD study included household surveys, demographic statistics, and other pertinent sources34.

The DALY is a broad metric that captures the total health loss due to a disease, calculating the years of healthy life lost from when the disease begins until death. It is utilized in the GBD study to assess disease burden40. DALYs are computed by combining the years lost to premature death (YLL) with the years of life affected by disability from illness or injury (YLD). Female infertility does not lead to death, so the DALYs for female infertility are the same as the YLDs.

For all final estimates, 95% uncertainty intervals (UI) were created using the 2.5th and 97.5th percentile values from 500 samples. Uncertainty was accounted for at each stage of the estimation process. Statistical significance is defined as a 95% UI, excluding 0. Results such as prevalence, DALYs, ASPR, and age-standardized DALYs rate have their uncertainty quantified and represented with point estimates and 95% UI41.

In this study, we used DisMod-MR, a Bayesian meta-regression tool, to model the non-fatal burden of female infertility42. The Mr-BRT (meta-regression—Bayesian, regularized, trimmed) tool, a sophisticated statistical instrument, is utilized in Global Burden of Disease (GBD) studies to estimate adjustment factors. This tool enhances the precision of estimates by accounting for biases and variations across diverse data sources. The Mr-BRT tool is particularly valuable in the context of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and other health metrics. By applying adjustment factors estimated through Mr-BRT, we can harmonize disparate datasets, thereby facilitating more accurate cross-study comparisons and strengthening the robustness of overall GBD estimates. In estimating the burden of ischemic heart disease in Isfahan, Iran, the researcher employed adjusted models to address issues of data incompleteness and misclassification, thereby underscoring the critical importance of precise data adjustment in burden estimation43. The GBD 2019 study on drug use disorders further exemplified the application of Bayesian meta-regression to analyze prevalence and incidence, illustrating the utility of advanced statistical techniques in global health research44.

Additionally, this study involved the collection of background information such as the SDI, for subsequent correlation analyses. The SDI values, which range from 0 to 1, reflect a country’s level of social development. According to the GBD 2021 study, countries are globally classified into five quintiles based on SDI—high, medium-high, medium, medium-low, and low—and 21 geographic regions42,43. Furthermore, this research utilized the Human Development Index (HDI), introduced by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in 1990, which comprises educational attainment, life expectancy, and gross national income components. The HDI serves as a comprehensive measure employed by the United Nations to evaluate the economic and social development levels of its Member States. Since its inception, the HDI has been instrumental in guiding the development strategies of developing countries. The UNDP annually publishes HDI values for nations worldwide, employing them in the Human Development Report to assess countries’ human development levels45,46.

Case definition

In GBD2021, Primary Female infertility is characterized by the failure to conceive a child after 5 years of unprotected intercourse, not attributed to any other infertility cause. Secondary infertility was identified in couples who desired a child and had been together for over 5 years without using contraception since their last live birth. The incidence of female infertility was assessed using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9): 628-628.9, V26-V26.49, V26.51, V26.8-V26.9, V59.7-V59.74 and Tenth Revision (ICD-10): N97-98.947. Based on the physiological characteristics of women, it was presumed that there was no burden of infertility in women under the age of 15. Consequently, the study population was segmented into seven age groups: 15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, 40–44, and 45–49 years.

Statistics

Initially, the global prevalence of female infertility, along with disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and corresponding age-standardized rates (ASRs), were reported for 2021. These were further delineated by different subtypes, including age, sociodemographic index (SDI), region, and country. The ASR was computed per 100,000 individuals using the following formula:

A: the number of age groups; ai: the age-specific rate in ith the age group. wi: the number of people in the corresponding ith age group among the standard population.

Temporal trends in disease burden from 1990 to 2021 were subsequently explored both globally and by subtype. Estimated Annual Percent Change (EAPC) values were calculated using linear regression models48. The EAPC was calculated using the formula: EAPC = 100 × (eβ − 1). A 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated using the linear regression model. Where β is calculated from the formula Y = α + βX + ε, with Y = ln (ASR), X denoting the calendar year, and ε as the error term. Based on these EAPC values, hierarchical cluster analysis was employed to identify patterns of change in the disease burden across the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) regions. These regions were classified into four categories: significant increase, small increase, stable or small decrease, and significant decrease.

Furthermore, the relationships among EAPC, ASR, and the Human Development Index (HDI) in 2021 were evaluated. Given the normal distribution of these three variables, Spearman correlation analysis was utilized to examine the associations. Projections of the future burden of disease from 2022 to 2050 were made using an autoregressive composite moving average (ARIMA) model under a maximum likelihood framework. The ARIMA model integrates autoregression, moving average, and moving weighted average, and is frequently employed in epidemiological studies to predict future variations using historical temporal patterns49. Statistical significance was established at a p value of less than 0.05. All data organization, management, and analysis were conducted using R software (version 4.2.2).

Data availability

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. The data can be found here: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/.

References

Weiss, M. S., Dokras, A. & Marsh, E. E. Beyond awareness—National infertility awareness week 2023. Fertil. Steril. 119, 570–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2023.02.026 (2023).

Caballero, B. Humans against obesity: Who will win?. Adv. Nutr. 10, S4–S9. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmy055 (2019).

Ding, C. et al. Association of weight-adjusted-waist index with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in China: A prospective cohort study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 32, 1210–1217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2022.01.033 (2022).

Gesink Law, D. C., Maclehose, R. F. & Longnecker, M. P. Obesity and time to pregnancy. Hum. Reprod. 22, 414–420. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/del400 (2007).

Chambers, G. M., Sullivan, E. A., Ishihara, O., Chapman, M. G. & Adamson, G. D. The economic impact of assisted reproductive technology: A review of selected developed countries. Fertil. Steril. 91, 2281–2294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.04.029 (2009).

Greil, A. L., Johnson, K. M., McQuillan, J. & Lacy, N. Are prior pregnancy outcomes relevant for models of fertility-specific distress or infertility helpseeking?. Hum. Fertil. (Camb.) 14, 160–166. https://doi.org/10.3109/14647273.2011.587229 (2011).

Fu, B. et al. Development and validation of an infertility stigma scale for Chinese women. J. Psychosom. Res. 79, 69–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.11.014 (2015).

Bezad, R., Omrani, S. E., Benbella, A. & Assarag, B. Access to infertility care services towards Universal Health Coverage is a right and not an option. BMC Health Serv. Res. 22, 1089. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08456- (2022).

Tarin, J. J., Garcia-Perez, M. A., Hamatani, T. & Cano, A. Infertility etiologies are genetically and clinically linked with other diseases in single meta-diseases. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 13, 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-015-0029-9 (2015).

Lerner-Geva, L. et al. Are infertility treatments a potential risk factor for cancer development? Perspective of 30 years of follow-up. Gynecol. Endocrinol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 28, 809–814. https://doi.org/10.3109/09513590.2012.671391 (2012).

Kvaskoff, M. et al. Endometriosis: A high-risk population for major chronic diseases?. Hum. Reprod. Update 21, 500–516. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmv013 (2015).

Mascarenhas, M. N., Flaxman, S. R., Boerma, T., Vanderpoel, S. & Stevens, G. A. National, regional, and global trends in infertility prevalence since 1990: A systematic analysis of 277 health surveys. PLoS Med. 9, e1001356. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001356 (2012).

Liu, X., Zhang, J. & Wang, S. Global, regional, and national burden of infertility attributable to PCOS, 1990–2019. Hum. Reprod. 39, 108–118. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dead241 (2024).

Liu, J. et al. spatiotemporal trends and age–period–cohort analysis for the burden of endometriosis-related infertility: An analysis of the global burden of disease study 2019. J. Pers. Med. 13, 1284. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13091284 (2023).

Lei, H.-L., Wei, H.-J., Ho, H.-Y., Liao, K.-W. & Chien, L.-C. Relationship between risk factors for infertility in women and lead, cadmium, and arsenic blood levels: A cross-sectional study from Taiwan. BMC Public Health 15, 1220. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2564-x (2015).

Sun, H. et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence and disability-adjusted life-years for infertility in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: Results from a global burden of disease study, 2017. Aging (Albany NY) 11, 10952–10991. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.102497 (2019).

García, D., Brazal, S., Rodríguez, A., Prat, A. & Vassena, R. Knowledge of age-related fertility decline in women: A systematic review. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 230, 109–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.09.030 (2018).

Kasaven, L. S. et al. Exploring the knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of women of reproductive age towards fertility and elective oocyte cryopreservation for age-related fertility decline in the UK: A cross-sectional survey. Hum. Reprod. (Oxf. Engl.) 38, 2478–2488. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dead200 (2023).

Huang, W., Li, X., Yang, H. & Huang, H. The impact of maternal age on aneuploidy in oocytes: Reproductive consequences, molecular mechanisms, and future directions. Ageing Res. Rev. 97, 102292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2024.102292 (2024).

Cohen, A. J. et al. Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: An analysis of data from the global burden of diseases study 2015. Lancet 389, 1907–1918. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30505-6 (2017).

Maheshwari, A., Hamilton, M. & Bhattacharya, S. Effect of female age on the diagnostic categories of infertility. Hum Reprod 23, 538–542. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dem431 (2008).

Mikwar, M., MacFarlane, A. J. & Marchetti, F. Mechanisms of oocyte aneuploidy associated with advanced maternal age. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 785, 108320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrrev.2020.108320 (2020).

Verdyck, P. et al. Aneuploidy in oocytes from women of advanced maternal age: Analysis of the causal meiotic errors and impact on embryo development. Hum. Reprod. 38, 2526–2535. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dead201 (2023).

May-Panloup, P. et al. Ovarian ageing: The role of mitochondria in oocytes and follicles. Hum. Reprod. Update 22, 725–743. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmw028 (2016).

Smits, M. A. J. et al. Human ovarian aging is characterized by oxidative damage and mitochondrial dysfunction. Hum. Reprod. 38, 2208–2220. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dead177 (2023).

Bai, J., Cui, J., Shi, F. & Yu, C. Global epidemiological patterns in the burden of main non-communicable diseases, 1990–2019: Relationships with socio-demographic index. Int. J. Public Health 68, 1605502. https://doi.org/10.3389/ijph.2023.1605502 (2023).

Davila-Cervantes, C. A. The burden of type 2 diabetes in adolescents and young adults in Mexico: Analysis from the global burden of disease study, 1990 to 2019. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 22, 1673–1684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40200-023-01299-x (2023).

Instituto Nacional de Estadistica e Informatica (INEI) and ORC Macro, Perú: Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud Familiar-ENDES Continua, 2009. Accessed at www.measuredhs.com, on 3 Nov. 2010 (2010).

Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J. et al. Air pollution and human fertility rates. Environ. Int. 70, 9–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2014.05.005 (2014).

Skakkebaek, N. E. et al. Male reproductive disorders and fertility trends: Influences of environment and genetic susceptibility. Physiol. Rev. 96, 55–97. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00017.2015 (2016).

Bongaarts, J. Human population growth and the demographic transition. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 364, 2985–2990. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2009.0137 (2009).

Tamirat, K. S., Tesema, G. A. & Tessema, Z. T. Determinants of maternal high-risk fertility behaviors and its correlation with child stunting and anemia in the East Africa region: A pooled analysis of nine East African countries. PLoS ONE 16, e0253736. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253736 (2021).

Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Tobacco or marijuana use and infertility: a committee opinion. Fertil. Steril. 121, 589–603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2023.12.029 (2024).

GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990-2021: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet 403, 2133–2161. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00757-8 (2024).

Yu, J. et al. Burden of female infertility in China from 1990 to 2019: A temporal trend analysis and forecasting, and comparison with the global level. Sex Health 20, 577–584. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH23029 (2023).

Xu, Q. et al. The incidence of asthma attributable to temperature variability: An ecological study based on 1990–2019 GBD data. Sci. Total Environ. 904, 166726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.166726 (2023).

GBD Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 396, 1204–1222. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9 (2020).

GBDRF Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 396, 1223–1249. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30752-2 (2020).

Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study (GBD 2021) Socio-demographic Index (SDI) 1950–2021 (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2024).

Murray, C. J. Quantifying the burden of disease: The technical basis for disability-adjusted life years. Bull. World Health Organ. 72, 429–445 (1994).

GBDRF Collaborators. Global burden and strength of evidence for 88 risk factors in 204 countries and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet 403, 2162–2203. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00933-4 (2024).

GBDSRF Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet Neurol. 23, 973–1003. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(24)00369-7 (2024).

Shams-Beyranvand, M., Farzadfar, F., Naderimagham, S., Tirani, M. & Maracy, M. R. Estimation of burden of ischemic heart diseases in Isfahan, Iran, 2014: Using incompleteness and misclassification adjustment models. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 16, 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40200-017-0294-6 (2017).

Shen, J. et al. Prevalence, incidence, deaths, and disability-adjusted life-years of drug use disorders for 204 countries and territories during the past 30 years. Asian J. Psychiatry 86, 103677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2023.103677 (2023).

Fallahzadeh, H., Khazaei, Z., Najafi, M. L., Pordanjani, S. R. & Goodarzi, E. Correction: Distribution incidence, mortality of tuberculosis and human development index in Iran: estimates from the global burden of disease study 2019. BMC Public Health 24, 661. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18021-y (2024).

Karamitanha, F., Ahmadi, F. & Fallahabadi, H. Difference between various countries in mortality and incidence rate of the atrial fibrillation based on human development index in worldwide: Data from global burden of disease 2010–2019. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 48, 101438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2022.101438 (2023).

Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 (GBD 2021)Causes of Death and Nonfatal Causes Mapped to ICD Codes (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2024). https://doi.org/10.6069/vd7t-zt25.

Ding, Q. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of ischemic stroke, 1990–2019. Neurology 98, e279–e290. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000013115 (2022).

Wei, W. et al. Time series prediction for the epidemic trends of monkeypox using the ARIMA, exponential smoothing, GM (1, 1) and LSTM deep learning methods. J. Gen. Virol. 104, 001839. https://doi.org/10.1099/jgv.0.001839 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge all participants of the GBD 2021 for their contribution.

Funding

This research received the found of General scientific research project of Zhejiang Provincial Department of Education (Y202351402), Zhejiang Provincial Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Program (2023ZL428) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 82204523).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jie Liu, Yi Qin: Study design, conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, software, visualization, and writing-original draft; Hui Liu, Yonglin Liu, Yi Yang: Formal analysis, software and visualization; Yumei Ning, Huijun Ye: Investigation, project administration, supervision, and writing-review and editing. All the authors have reviewed and approved the manuscript for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Qin, Y., Liu, H. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of female infertility and trends from 1990 to 2021 with projections to 2050 based on the GBD 2021 analysis. Sci Rep 15, 17559 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01498-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01498-x