Abstract

To address the problem of relying on manual experience to determine the number of cluster centers, this paper introduces an approach for evaluating the performance degradation of rolling bearings using the clustering by fast search (CFS) algorithm. Few studies have explored the application of CFS for bearing performance degradation assessment (PDA). Unlike traditional cluster models, such as Fuzzy C-Means, Gustafson–Kessel, Gath–Geva, K-means, and K-medoids, CFS automatically selects the cluster centers according to local density and distance. First, the original vibration signals are processed using local mean decomposition to obtain several product functions (PFs). The top two PFs are selected based on the correlation coefficient and then analyzed using singular-value decomposition to extract the top two singular values (SV1 and SV2). Second, SV1 and SV2 are used as input to the CFS algorithm to identify the cluster centers automatically. Lastly, a confidence value is calculated based on the differences between the sample features and the identified clustering centers for bearing PDA. The results show that CFS outperforms other clustering methods and models, including root mean square, kurtosis, Shannon entropy, approximate entropy, and permutation entropy, detecting early-stage degradation more precisely.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rolling bearings are key components in mechanical systems, and their operation is directly related to overall performance. A large body of data shows that nearly one-third of rotating equipment failures are attributable to the failure of rolling bearings, leading to high equipment downtime costs and serious economic losses1. Consequently, accurate bearing health assessment is critical. Vibration signal analysis is widely used in bearing state monitoring.

In the initial phase of vibration signal analysis, the raw signal is first decomposed to reveal underlying characteristics. This step has been facilitated by various signal processing techniques. Among these methods, time–frequency domain statistical analysis provides detailed information about signal behavior over time and frequency. Wavelet packet decomposition (WPD) is also effective in capturing both temporal and frequency details of non-stationary signals2,3,4,5. Empirical mode decomposition (EMD)6,7 and ensemble empirical mode decomposition (EEMD)8,9,10 are widely used for decomposing complex signals into intrinsic mode functions, enabling more detailed analysis. Local mean decomposition (LMD)11,12 is an alternative approach that extracts product functions (PFs) capturing the local characteristics of the signal, providing a different perspective on signal decomposition.

Root mean square (RMS) and kurtosis, two statistical measures in the time–frequency domain, are among the most common indices for evaluating rolling bearing performance degradation13. Tse et al14. constructed the performance degradation assessment (PDA) model for bearings using RMS to monitor bearing health as vibration energy changes. Shen et al.15 used an effective amplitude-based approach to extract bearing degradation features by eliminating frequency bands without critical information while retaining those containing degradation signals. In the field of bearing PDA, statistical measures such as Shannon entropy (SHE), approximate entropy (AE), and permutation entropy (PE) are effective analytical tools16. Ma et al.17 used AE to model bearing degradation and found that as degradation increased, the signal’s frequency components changed, resulting in decreased signal regularity and increased AE values. Compared with AE, PE depends only on the relative order of signal values and shows strong adaptability to nonlinear signal changes, offering an advantage in processing efficiency18. Jiang et al.19 proposed an improved multiscale PE technique to address the limitations of the coarse-graining process. Zheng et al.20 introduced reverse PE as a nonlinear dynamic parameter that integrates distance information into time series of different lengths.

In mechanical signal processing, vibration signals from rolling bearings typically exhibit nonlinear behavior, presenting a challenge for effective adaptive signal decomposition using time–frequency analysis tools such as WPD. WPD implementation depends on the selected wavelet basis and decomposition level, which limits its adaptability. By contrast, EMD21 can decompose the signal into several intrinsic mode functions (IMFs) and a residual, demonstrating adaptive decomposition. EEMD22 is an optimized version of EMD that improves the adaptive decomposition of complex signals by accounting for their local temporal characteristics. LMD23 is an adaptive time–frequency analysis method that extracts instantaneous amplitude and frequency directly from the signal without using the Hilbert transform (HT). It relies on smoothing the local mean and amplitude, avoiding the errors caused by cubic spline interpolation in EMD and ensuring accurate instantaneous frequency and amplitude measurement24. Researchers often combine LMD with diverse signal processing techniques to capture unique fault signals across different fault modes. For example, Huang et al.25 developed an analysis framework integrating LMD with advanced noise suppression techniques to enhance the identification of subtle fault signals. Zheng et al.26 proposed a method for analyzing gear faults by combining LMD with the morpho-fractal dimension and evaluating the mutual information entropy between the PFs and the original signals to select signal components with the richest fault features. Liu et al.27 combined the generative wavelet transform with LMD to propose a fault identification scheme for rotating machinery. These studies highlight LMD’s ability to capture intrinsic features of vibration signals and demonstrate its key role in the early-stage detection of rolling bearing degradation.

After processing the original signal with LMD, the next key step is constructing the PDA model. Cluster analysis, a widely used technical method in PDA, enables comprehensive health assessment of the operation status of mechanical equipment. Various clustering techniques are effective for identifying and classifying failure modes in fault diagnosis scenarios without explicit labels. Pan et al.28 proposed a strategy combining WPD with the Fuzzy C-Means (FCM) algorithm to support bearing PDA. Although these new degradation metrics can monitor bearing degradation near the end of service life, their sensitivity to detect early signs of degradation remains limited. Wang et al.29 adopted an analytical approach incorporating fractal dimension theory and FCM clustering to explore the degradation patterns of equipment performance.

Although FCM clustering is widely used for its simplicity, it is mainly limited to datasets with uniform properties, as it relies on Euclidean distance to measure similarity between samples30. To address this limitation, Pimentel et al.31 introduced an improved FCM variant that increases adaptability to data distribution by incorporating an adaptive distance metric and a covariance matrix. However, the FCM and Gustafson–Kessel (GK) algorithms remain limited in handling non-spherical datasets, which are common in practical engineering applications. To address this, Gath–Geva (GG) clustering was introduced. This method uses fuzzy maximum likelihood estimation to measure distances between sample points and shows adaptability to various data forms32,33. Building on this, Li et al.34 developed a GG-based strategy specifically for rolling bearing PDA to improve the accuracy and reliability of fault diagnosis.

While existing clustering techniques play an important role in bearing condition analysis, the clustering models discussed above present several limitations:

(1) They often rely on expert knowledge to determine the number of clusters and their centers.

(2) The number of clusters is typically preset into three categories (normal, slight, and severe) based on operating conditions. This manual judgment can misinterpret degradation trends, especially when bearings exhibit only two states (normal and severe).

(3) Few studies have examined the use of clustering by fast search (CFS) for bearing PDA.

To solve the reliance on manual experience for determining the number of cluster centers, Rodriguez et al.35 proposed a CFS model based on local density and sample spacing. This model automatically identifies optimal clustering centers and reduces the interference of manual intervention. In reference36, after decomposing the rolling bearing vibration signal using EEMD, CFS was applied to identify bearing faults. Xu et al.37,38,39,40,41 proposed a fault feature extraction method based on a denoising autoencoder and CFS for rolling bearing fault diagnosis. Their approach also included an automatic fault diagnosis framework that enables fault identification through data labeling.

This paper presents a new method for rolling bearing PDA based on LMD, singular value decomposition (SVD), and CFS. First, the rolling bearing vibration signal is preprocessed using LMD, and all obtained PFs are analyzed using SVD. Second, the top two singular values (SVs) are selected based on their correlation with PFs. These SVs serve as the input to the CFS algorithm to automatically determine the number of clusters and their centers. Finally, a confidence value (CV) is used to perform the bearing PDA.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

(1) Because few studies have applied CFS to bearing PDA, this paper lays the foundation for its initial use in this field.

(2) To reduce dependence on manual experience in determining the number of cluster centers, this paper uses CFS for bearing PDA to automatically identify cluster centers.

(3) To demonstrate the LMD–SVD–CFS algorithm’s superiority in bearing performance degradation assessment, it was compared with several widely used time-domain feature indices and clustering algorithms, including RMS, kurtosis, SHE, AE, PE, K-means, K-medoids, FCM, GK, and GG.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the basic theory of LMD, SVD, and CFS. Section 3 describes the experimental data sources and the methodology steps. In Sect. 4, the experimental results are presented, and the proposed method is compared with existing techniques. Finally, Sect. 5 summarizes the main findings of the study.

Basic theory of LMD, SVD, and CFS

Theoretical framework of LMD

LMD identifies the local extrema of the signal and applies smoothing techniques to the raw data sequence to separate the pure frequency-modulated component from the signal envelope. Each PF is then reconstructed by multiplying the pure frequency-modulated signal by its corresponding envelope. This process is repeated to extract all PF components from the signal. The detailed computational procedure is as follows:

(1) For a given original vibration signal series\(\:\:X\left(i\right)\:1\:\:i\:\:N\), where \(\:N\:\)represents the length of the sample, the initial LMD task focuses on accurately identifying all local extremum points within the sequence (labeled \(\:{n}_{i}\)). The next step is to calculate the mean value, denoted as \(\:{m}_{i}\), and then estimate the signal envelope (denoted as \(\:{a}_{i}\)).

The obtained average extreme points \(\:{m}_{i}\), identified using the method, are connected by drawing straight lines and then applying a moving average algorithm to smooth the data. The local mean of the sequence \(\:{m}_{local\:mean}\left(i\right)\) and the corresponding envelope estimation function \(\:{a}_{\text{e}\text{n}\text{v}\text{e}\text{l}\text{o}\text{p}\text{e}\:\text{e}\text{s}\text{t}\text{i}\text{m}\text{a}\text{t}\text{i}\text{o}\text{n}}\left(i\right)\) are then obtained.

(2) In the second stage, \(\:{m}_{local\:mean}\left(i\right)\) is extracted from the original time series\(\:\:X\left(i\right)\), generating the residual component C, the detailed computation of which is as follows:

(3) By demodulating C in step (2), \(\:s\left(i\right)\:\)is calculated as follows:

(4) Repeat the above steps to obtain the next envelope estimation function,\(\:{a}_{\text{e}\text{n}\text{v}\text{e}\text{l}\text{o}\text{p}\text{e}\:\text{e}\text{s}\text{t}\text{i}\text{m}\text{a}\text{t}\text{i}\text{o}\text{n}}\left(j\right).\) If \(\:{a}_{\text{e}\text{n}\text{v}\text{e}\text{l}\text{o}\text{p}\text{e}\:\text{e}\text{s}\text{t}\text{i}\text{m}\text{a}\text{t}\text{i}\text{o}\text{n}}\left(j\right)=1\), \(\:s\left(i\right)\) is recognized as a pure frequency modulation signal. If not, the iterative process continues until \(\:{a}_{\text{e}\text{n}\text{v}\text{e}\text{l}\text{o}\text{p}\text{e}\:\text{e}\text{s}\text{t}\text{i}\text{m}\text{a}\text{t}\text{i}\text{o}\text{n}}\left(i+1\right)=1\) and the sequence \(\:s\left(i\right)\le\:1\).

(5) The PFs are calculated as follows:

where \(\:{a}_{i}\) denotes the instantaneous amplitude function of \(\:PF\left(i\right)\)

(6) After completing the above steps, a new data sequence is obtained, denoted as \(\:C\left(1\right)\). Steps (1) to (5) are then applied to \(\:C\left(1\right)\), with successive iterations continuing until \(\:C\left(1\right)\) becomes a monotonically increasing or decreasing function.

After completing these steps, the original sequence \(\:X\left(i\right)\) is decomposed into the sum of \(\:PF\left(i\right)\) components and a monotonic function \(\:C\left(i\right)\).

Theoretical framework of SVD

As previously mentioned, SVD is used to calculate and extract the SVs from the PFs obtained in Sect. 2.1. The SVD process is described as follows:

Each selected PF matrix \(\:T\) is decomposed as:

where \(\:U\) and \(\:V\) are orthogonal matrices satisfying \(\:U{U}^{T}=1\) and \(\:V{V}^{T}=1\). Q is the singular value matrix, containing all-positive diagonal elements. SV matrices exhibit properties such as robustness, insensitivity to rotation, and consistent response to changes in scale. These characteristics make SVD a suitable tool for capturing fault features in bearing vibration signals.

Theoretical framework of CFS

CFS is defined by two key characteristics. First, data points are densely concentrated within local regions, meaning that no neighboring region has a higher density than the core region. Second, each core is far from other high-density data points, ensuring clear separation and uniqueness of the clusters. The specifics are as follows:

(1) Set up a dataset \(\:X=\{{x}_{1},{x}_{2},\:,\:{x}_{N}\}\), where\(\:\:X\) is the matrix of all SV vectors obtained in Sect. 2.2.

For this dataset, a Euclidean distance \(\:{d}_{ij}\) between any two samples \(\:{x}_{i}\) and\(\:\:{x}_{j}\:\)is calculated as:

(2) Calculate the local density \(\:{\rho\:}_{i}\:\)of the ith sample \(\:{x}_{i}\) using:

Here, \(\:{\rho\:}_{i}\:\)represents the total number of distances \(\:{d}_{ij}\:\le\:{d}_{c}\:\)between \(\:{x}_{i}\) and\(\:\:{x}_{j}\), where \(\:{d}_{c}\)is a cut-off distance. The data point xi itself is not considered.

(3) Calculate the distance \(\:\delta\:\). Let \(\:{\left\{{\text{q}}_{\text{i}}\right\}}_{\text{i=}\text{1}}^{N}\) represent a descending order of \(\:{\left\{{\rho}_{\text{i}}\right\}}_{\text{i}\text{=1}}^{\text{N}}\), such that:

Then, calculate \(\:{\delta\:}_{{q}_{i}}\) as:

The variable \(\:{\delta\:}_{{q}_{i}}\:\)is defined as the distance to the furthest point in the dataset if \(\:{x}_{i}\:\)has the highest local density. If\(\:{\:x}_{i}\) does not have this property, \(\:{\delta\:}_{{q}_{i}}\:\)is the distance to the nearest point with higher density.

(4) Following the calculation process of steps (2) and (3), assign each point in the dataset a \(\:\gamma\:\) coordinate value, and then sort them in descending order.

(5) Determine the cluster centers based on the \(\:\gamma\:\) coordinates of each data point. According to23, a data point \(\:{x}_{i}\:\)is more likely to be a cluster center if it has a higher \(\:\gamma\:\) value. Accordingly, the \(\:\gamma\:\) values are sorted in descending order, and the points with higher values are prioritized as potential cluster centers. A significant difference in \(\:\gamma\:\) values become a key indicator for distinguishing cluster centers from non-cluster centers. Based on this jump feature, data points showing sudden changes in coordinate values are identified and selected as clustering centers.

(6) Determine local membership based on whether the distance between a data point and a cluster center does not exceed the threshold\(\:{\:d}_{c}\). This decision is guided by the parameter \(\:{\rho\:}_{i}\). Based on this criterion, the data are classified into different clusters.

Dataset source and procedure for the proposed method

Experimental platform and data source

The experimental data for the rolling bearing study originate from the PRONOSTIA platform at the FEMTO-ST Institute, University of Franche-Comté, France. A detailed description of the dataset is provided in reference42. The PRONOSTIA platform is shown in Fig. 1(a). The experimental platform consists of three parts: the rotating part, the load part; and the testing part.

(1) Rotating part: The motor has a power of 250 W and a maximum speed of 2830 rpm, ensuring that the second shaft rotates at 2000 rpm.

(2) Load part: This section consists of a pneumatic jack that applies a dynamic load of 4000 N to the bearing, as shown in Fig. 1(b).

(3) Testing part: The bearing degradation data fall into two main categories: vibration data and temperature data. The vibration sensor consists of two miniature accelerometers positioned at 90° to each other, as shown in Fig. 1(c). One accelerometer is mounted along the vertical axis and the other along the horizontal axis. Both are radially mounted on the outer ring of the bearing, with a sampling frequency of 25.6 kHz. The temperature sensor is a resistance temperature detector (RTD) installed in a hole near the outer bearing ring, with a sampling frequency of 0.1 Hz.

The experimental data under a 4000 N load and a rotational speed of 1800 rpm include seven rolling bearings, among which Bear11 to Bear14 are used in this study. A detailed description of the data is provided in Table 1, where 2560n is the length of each sample. The total number of data samples for Bear11, Bear12, Bear13, and Bear14 is 2803, 871, 911, and 1139, respectively. The platform operates at a speed of 1800 rpm, and the sampling frequency is 25.6 kHz.

Procedure for the proposed method

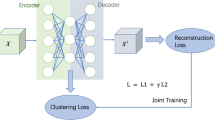

The procedure for the proposed method consists of three parts: (1) PF extraction and selection; (2) SVD decomposition and clustering; (3) CV extraction for bearing PDA.

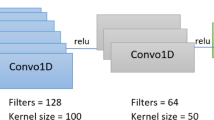

(1) PF extraction and selection: LMD is used to decompose the original vibration signal for different bearings. The correlation coefficient is then used to calculate the similarity between each PF and the original vibration signal. The top two PFs, based on their correlation coefficients, are selected for the subsequent SVD decomposition.

(2) SVD decomposition and clustering: SVD is applied to calculate the SVs. The first two SVs (SV1 and SV2) are used as input for various clustering models (CFS, FCM, GK, GG, K-means, and K-medoids) to identify cluster centers representing different operating conditions: normal state, incipient degradation, and severe degradation.

(3) CV extraction for bearing PDA: The CV is introduced as a new indicator to assess bearing health status. The degree of difference between the feature vectors [SV1, SV2] and the predefined cluster centers is evaluated using a specific mathematical model. CV is calculated as.

where \(\:D\) is the distance between any two samples, and S is a scaling factor associated with the cluster centroids. CV represents the similarity between ith sample \(\:{\:x}_{i}\) and the cluster center under normal conditions. A CV closer to 1 indicates that the sample is in a “normal” state, while a CV closer to 0 indicates an “abnormal” state (e.g., slight or severe degradation).

Finally, to demonstrate the superiority of the proposed method, a series of time–frequency domain characterization tools, including RMS, SHE, AE, PE, and kurtosis, were adopted. In addition, various cluster analysis techniques such as FCM, GK, GG, K-means, and K-medoids were applied to provide a comprehensive assessment of the performance status of the rolling bearings. This procedure is illustrated in Fig. 2

Experiment and comparison analysis

Original vibration signal

This section presents visualizations of the raw vibration signals listed in Table 1. As revealed in Fig. 3, Bear11, Bear13, and Bear14 experience three different operating states: normal, slight, and severe. By contrast, Bear12 exhibits only two states—normal and severe degradation—highlighted by the red dashed box in the figure.

In Fig. 3, the vibration amplitudes of Bear11 and Bear13 increase gradually over time. However, Bear12 and Bear14 show sudden changes in amplitude, with the change in Bear12 being especially abrupt. The amplitude pattern of Bear14 is more complex; the sudden change can be divided into two phases: a slightly degraded phase, indicated by the red solid box, and a severely degraded phase, indicated by the red dashed box. Most cluster analysis methods, including FCM, GK, GG, K-means, and K-medoids, require the number of clusters to be predetermined based on expert knowledge or subjective judgment.

In the subsequent examples, CFS is employed to construct the PDA model for rolling bearings without specifying the number of clusters.

LMD decomposition and SV extraction

As mentioned in Sect. 4.1, all original vibration signal samples are first decomposed using LMD. The resulting PFs obtained from Bear11 to Bear14 are shown in Fig. 4, where C denotes the residual component. As shown in the figure, the vibration amplitudes of the top two PFs are the largest and second largest, suggesting that these components contain valuable information.

To verify the potential of the top two PFs as effective decomposition components, correlation analysis was used to quantify the strength of the relationship between the original signal and each individual PF. A correlation value closer to 1 indicates a stronger correlation. As illustrated in Fig. 5, PF1 and PF2 show the highest correlation values, highlighting their significance as key decomposition components.

To visualize the data, the singular values corresponding to PF1 and PF2—SV1 and SV2—were extracted using SVD and used as the input parameters for the CFS algorithm to construct the rolling bearing PDA model. As shown in Fig. 6, SV1 and SV2 significantly reflect the degradation paths of bearing performance. In particular, SV1 shows a high sensitivity in tracking the degradation trend. However, in the normal state, an oscillation is observed (especially for Bear12), which can be attributed to noise present in the vibration signal under normal conditions, as seen in Fig. 3. However, the following experiment results demonstrate that the proposed method offers better stationarity when using CFS and the CV compared to using only SV obtained via SVD.

CFS clustering and PDA using CV

To accurately identify the core elements of clustering, SV1 and SV2 were used as input features for the CFS algorithm.

According to reference27, the appropriate DC value should be selected such that the number of neighboring points of each data point within its DC range is 1–2% of the total number of data points. This helps ensure accuracy and efficiency in the clustering process. In dataset X, any sample xi has a distance relationship with the remaining N − 1 data points, resulting in N × (N − 1) independent distance measures. However, because distances are symmetric, this count includes redundancy. The total number of unique, independent distance values is M = 0.5 N × (N − 1).

By sorting the distance dij (i < j) in Eq. (10) in ascending order, the distance sequence d1 ≤ d2 ≤‧‧‧≤dM is obtained. If dc is selected as dk, where k ∈ {1, 2, …, M}, then approximately k/M of all N × (N − 1) distances are less than dc, which equals approximately (k/M) × N × (N − 1). After averaging this across all data points, each point has approximately (k/M) × (N − 1) ≈ (k/M) × N neighbors. The ratio k/M is given, and the value of dc is determined. If dc is set too high, the local density value ρi of each data point xi becomes excessively large, reducing the discrimination between points. This may cause a single cluster to be mistakenly split into multiple subclusters. In the study, dc is set using a k/M ratio of 1.5%.

Within the framework of the CFS, Bear11 and Bear12 were analyzed based on the local density ρ and distance δ values computed in Eqs. (11–12), and the results are presented in Fig. 7. In Fig. 7(a), three sample points are clearly separated from the rest in terms of local density and distance, and the p and t values of these points are significantly higher than those of the remaining samples, showing a significant “jumping” characteristic. Based on this observation, these three samples were selected as cluster centers representing different health states of the bearings, covering the full degradation process from normal to slight to severe. Figure 7(b) shows that two sample points also exhibit “jumps”. These observations confirm the effectiveness of the CFS algorithm in automatically identifying cluster centroids.

The two-dimensional clustering results for Bear11 to Bear14 are shown in Fig. 8, where the red square points represent the cluster points. All samples are separated well by using CFS. Subsequently, a comprehensive assessment of the performance status of the rolling bearings was conducted based on the CVs calculated using Eq. (13). Figure 9 shows the distribution of CVs obtained using different cluster centroids on the datasets of Bear11 to Bear14.

As shown in Fig. 9(a), the CV of Bear11 remains stable during the “normal” operating phase. However, as the bearing condition progresses into the “slight” and “severe” states, the CV shows a decreasing trend. By contrast, the CVs of Bear12 display an almost continuous straight-line pattern during the initial stages of the observation period, as shown in Fig. 9(b), but a clear downward trend appears at the end. This is due to a sharp increase in the original vibration signal of Bear12 at the end of this stage. Compared to the SVs for Bear12 shown in Fig. 6, the CVs remain stable in the “normal” state, while the SVs exhibit noise. The CV curves in Fig. 9(b) and Fig. 9(d) for Bear13 and Bear14 also show good overall stability. An extended view of Fig. 9 is provided in Fig. 10. Based on this visualization, performance degradation in Bear11 can be observed: its health first drops to the “slightly degraded” level at data point 1491, with an amplitude of 0.9724, then rises to 0.9899 at data point 1492. Further degradation occurs at data point 2748, when the bearing reaches the “severe” state. Similarly, the health status of Bear12 worsens sharply at data point 828, rapidly transitioning from “normal” to “severe”. These observations highlight the efficiency of CFS in achieving PDA for rolling bearings. A key advantage of this method is that it does not require a predetermined number of clusters.

Comparison analysis

Comparison with FCM, GK, and GG

To demonstrate the superiority of the proposed method, several common techniques, such as FCM, GK, and GG, are used to build PDA models and calculate the CV. For the FCM, GK, and GG models, the number of cluster centers c for Bear11, Bear13, and Bear14 is set to 3, as these bearings exhibit three health states. For Bear12, c is set to 2, as it only includes two states: normal and severe. The value of the termination tolerance is also specified for these models. The results of the two-dimensional clustering are shown in Fig. 10. As shown in Figs. 11 and 12, and 13, the corresponding CV distributions, calculated using various cluster centers according to Eq. (13), are presented in Figs. 14 and 15, and 16.

(1) As shown in Fig. 12(a), several samples in different states overlap for Bear11 when using GK, whereas in Fig. 8(a), all samples are separated well using CFS. In Fig. 15, many samples for Bear11, Bear12, and Bear13 overlap when GG is applied. This is especially evident for Bear12, where only two states are present and should be clearly divided; however, some severe samples overlap with normal samples. By contrast, Fig. 9(b) shows that all samples are separated well. For Bear11, all CVs under different conditions using various clustering center points (“normal”, “slight”, and “severe”) appear similar in Fig. 16(a). However, Fig. 10(a) shows a clear increasing trend when the “slight” and “severe” cluster centers are used, making it easier to distinguish between different health states.

(2) For Bear12, the number of clusters must be manually adjusted before building the PDA model, which requires expert judgment. Typically, bearing health is divided into three states: normal, slight, and severe. However, Bear12 contains only two states: normal and severe. This mismatch can lead to errors when determining the health state using FCM, GK, or GG. The results show that CFS can accurately and automatically identify the health condition of the rolling bearing.

(3) These results demonstrate that the performance of CFS is superior to that of FCM, GK, and GG.

Comparison with K-means and K-medoids

As with the FCM, GK, and GG models, certain parameters for K-means and K-medoids must be pre-configured before calculation. The number of clusters c for K-means and K-medoids is the same as that used for FCM, GK, and GG. The results of the two-dimensional clustering using K-means and K-medoids are shown in Figs. 17 and 18, respectively, and the corresponding CVs are presented in Figs. 19 and 20.

The CVs for Bear11 using K-means and K-medoids are shown in Fig. 19(a). In Fig. 20(a), under the “slight” condition, the CVs increase gradually, whereas with CFS, all CVs under the “slight” condition increase sharply, as shown in Fig. 9(a), with an obvious jump. This indicates that degraded states such as “normal” and “slight” are easier to distinguish for Bear11 when using CFS. A similar pattern is also observed in the “severe” state in Fig. 9(a). In addition, CVs under the “normal” and “slight” conditions of Bear11 in Fig. 19(a) appear similar at first glance, while in Fig. 9(a), they differ clearly. Moreover, the number of clusters must be pre-set before building the PDA model, and expert knowledge is required to determine the cluster number when CFS is used.

Comparison with RMS and kurtosis

In this section, RMS and kurtosis are employed as metrics to assess the health state of all rolling bearings. The RMS and kurtosis values are shown in Figs. 21 and 22.

(1) Compared with RMS and kurtosis, the CV curves in Figs. 9 and 10 are very smooth and stable within the red dashed rectangle, without obvious noise. By contrast, the curves in Figs. 21 and 22 show significant noise under normal conditions, especially for Bear12. In Fig. 22, the noise in the kurtosis curve is particularly pronounced.

(2) Engineers may easily misjudge the degradation state of the bearing due to noise points that appear to transition from the normal to the slight or severe state, such as the red data points within the red dashed rectangle in Figs. 21 and 22. For example, Bear12 remains in the normal state until data point 828, yet many noise points within the red dashed rectangle have RMS values greater than that at point 828. However, in Fig. 10(b), no data points appear in the red dashed rectangle area after data point 828. Therefore, the noise in the RMS values before point 828 may lead to misjudgment of the bearing’s degradation state. The kurtosis values in Fig. 22 show similar behavior.

(3) Compared with RMS and kurtosis, CFS provides superior performance in PDA. These findings indicate that the CFS algorithm effectively captures and assesses the performance status of rolling bearings.

Comparison with RMS and kurtosis

This section provides a comprehensive assessment of the performance state of rolling bearings using three metrics: SHE, AE, and PE. Before calculating these entropy values, several key parameters must be defined.

For the calculation of AE, two key parameters must be predefined: the embedding dimension and the tolerance. Increasing the embedding dimension helps capture richer data features but also increases the computational load. Therefore, an embedding dimension of 2 was selected. For the tolerance parameter, the recommended range is 0.1 to 0.25 times the SD of the original dataset17.

PE: Before data analysis, two key parameters must be determined: the embedding dimension and the time lag. Researchers generally recommend keeping the embedding dimension in the range of 3 to 7, as when the dimension exceeds this range, the efficiency of calculation may decrease, particularly during phase space reconstruction, and lead to the loss of subtle features in the vibration signals. In addition, if the time lag value is set above 5, the algorithm may fail to capture the small fluctuations in the vibration signal, affecting the accuracy of the analysis. Based on these considerations, an embedding dimension of 6 and a time lag of 3 were selected to ensure both accurate and efficient analysis. The degradation curves obtained using SHE, AE, and PE are presented in Figs. 23, 24 and 25.

(1) Compared with Figs. 23, 24 and 25, the CV curves in Figs. 9 and 10 are smooth and stable within the red dashed rectangle, without noticeable noise. By contrast, many noisy data points appear in the red dashed rectangle area in Fig. 23(c), Fig. 24, and Fig. 25.

(2) The AE curve in Fig. 24(b) shows some noise, especially for Bear12. It is difficult to distinguish the normal and severe conditions because of the noisy data points in the red dashed rectangle. The same phenomenon is observed in Fig. 25(d) when using the PE model. Therefore, engineers may misjudge the degradation state of the bearing because these noise points appear to transition from the normal to the slight or severe state when using SHE, AE, and PE.

(3) Compared with SHE, AE, and PE, CFS provides superior performance in PDA. These findings demonstrate that the CFS algorithm is effective in capturing and assessing the performance status of rolling bearings.

Conclusion

To address the problem of predetermining the number of clusters, this paper introduces the CFS algorithm for bearing PDA. Very few studies have focused on applying CFS in this context. The advantages and limitations of this study are as follows:

Advantages:

(1) The CFS algorithm uses the local density of data points and a distance metric to dynamically determine the optimal number of clusters, eliminating reliance on manual experience.

(2) This paper lays the groundwork for the initial application of CFS in the field of bearing PDA.

Disadvantages: The selection of the optimal cut-off distance parameter \(\:{d}_{c}\) in CFS remains a key challenge in this study. Particle swarm optimization, genetic algorithms, and other computational methods have been widely used in other fields. We plan to explore these approaches in future work to improve the selection of \(\:{d}_{c}\).

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Li, H., Zhang, Z., Li, T. & Si, X. A review on physics-informed data-driven remaining useful life prediction: challenges and opportunities. Mech. Syst. Signal. Process. 209, 111120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2023.111120 (2024).

Tse, P. W. & Wang, D. Enhancing the abilities in assessing slurry pumps’ performance degradation and estimating their remaining useful lives by using captured vibration signals. J. Vib. Control. 23, 1925–1937. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077546315619066 (2017).

Habbouche, H., Benkedjouh, T. & Zerhouni, N. Intelligent prognostics of bearings based on bidirectional long short-term memory and wavelet packet decomposition. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 114, 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-021-06855-4 (2021).

Lu, G., Wen, X., He, G., Yi, X. & Yan, P. Early fault warning and identification in condition monitoring of bearing via wavelet packet decomposition coupled with graph. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 27, 3155–3164. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMECH.2021.3083114 (2021).

Moumene, I. & Ouelaa, N. Gears and bearings combined faults detection using optimized wavelet packet transform and pattern recognition neural networks. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 120, 4335–4354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-022-08843-8 (2022).

Cheng, G., Wang, X. & He, Y. Remaining useful life and state of health prediction for lithium batteries based on empirical mode decomposition and a long and short memory neural network. Energy 232, 121022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2021.121022 (2021).

Chen, G., Yan, C., Meng, J., Wang, Z. & Wu, L. Health condition monitoring of bearings based on multifractal spectrum feature with modified empirical mode decomposition-multifractal detrended fluctuation analysis. Struct. Health Monit. 21, 2618–2640. https://doi.org/10.1177/14759217221075240 (2022).

Faysal, A., Ngui, W. K. & Lim, M. H. Noise eliminated ensemble empirical mode decomposition for bearing fault diagnosis. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 9, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42417-021-00334-6 (2021).

Gao, Z., Liu, Y., Wang, Q., Wang, J. & Luo, Y. Ensemble empirical mode decomposition energy moment entropy and enhanced long short-term memory for early fault prediction of bearing. Measurement 188, 110417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2021.110417 (2022).

Zhong, C., Wang, J. S. & Sun, W. Z. Fault diagnosis method of rotating bearing based on improved ensemble empirical mode decomposition and deep belief network. Meas. Sci. Technol. 33, 085109. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6501/ac5b3a (2022).

Goyal, D. et al. An intelligent self-adaptive bearing fault diagnosis approach based on improved local mean decomposition. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 16, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12008-021-00813-w (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Research on the composite fault diagnosis of gearbox based on local mean decomposition and hilbert demodulation. Meas. Control. 56, 1350–1358. https://doi.org/10.1177/00202940231177341 (2023).

Wang, D., Tsui, K. L. & Miao, Q. Prognostics and health management: a review of vibration based bearing and gear health indicators. IEEE Access. 6, 665–676. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2017.2774262 (2017).

Tse, P. W. & Wang, D. State space formulation of nonlinear vibration responses collected from a dynamic rotor-bearing system: an extension of bearing diagnostics to bearing prognostics. Sensors 17, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/s17020369 (2017).

Chen, X. et al. Remaining life predictions of rolling bearing based on relative features and multivariable support vector machine. J. Mech. Eng. 49, 183–189. https://doi.org/10.3901/JME.2013.02.183 (2013).

Kosasih, B. Y. et al. Degradation trend Estimation and prognosis of large low speed slewing bearing lifetime. Appl. Mech. Mater. 493, 343–348 (2014). https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.493.343

Ma, J. et al. Rolling bearing fault diagnosis based on refined composite multi-scale approximate entropy and optimized probabilistic neural network. Entropy 23, 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/e23020259 (2021).

Zhao, C. et al. Rolling mill bearings fault diagnosis based on improved multivariate variational mode decomposition and multivariate composite multiscale weighted permutation entropy. Measurement 195, 111190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2022.111190 (2022).

Jiang, Q. et al. Bearing early fault diagnosis based on an improved multiscale permutation entropy and SVM. Shock Vib. 2227148 (2022). (2022). https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/2227148

Zheng, J. et al. Composite multi-scale phase reverse permutation entropy and its application to fault diagnosis of rolling bearing. Nonlinear Dyn. 111, 459–479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-022-07857-x (2023).

Delprete, C. et al. Bearing health monitoring based on the orthogonal empirical mode decomposition. Shock Vib. 2020 (8761278). https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8761278 (2020).

Gu, J. & Peng, Y. An improved complementary ensemble empirical mode decomposition method and its application in rolling bearing fault diagnosis. Digit. Signal. Process. 113, 103050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsp.2021.103050 (2021).

Yang, C., Lai, Y. & Li, Q. Research on electromagnetic acoustic emission signal recognition based on local mean decomposition and least squares support vector machine. J. Comput. Commun. 11, 70–83. https://doi.org/10.4236/jcc.2023.115005 (2023).

Xiong, Z., Han, C. & Zhang, G. Fault diagnosis of anti-friction bearings based on Bi-dimensional ensemble local mean decomposition and optimized dynamic least square support vector machine. Sci. Rep. 13, 17784. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-44843-8 (2023).

Huang, N. et al. Mechanical fault diagnosis of high voltage circuit breakers with unknown fault type using hybrid classifier based on LMD and time segmentation energy entropy. Entropy 18, 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/e18090322 (2016).

Zheng, Z. et al. Gear fault diagnosis method based on local mean decomposition and generalized morphological fractal dimensions. Mech. Mach. Theory. 91, 151–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2015.04.009 (2015).

Liu, Z. et al. A hybrid fault diagnosis method based on second generation wavelet de-noising and local mean decomposition for rotating machinery. ISA Trans. 61, 211–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isatra.2015.12.012 (2016).

Pan, Y., Chen, J. & Li, X. Bearing performance degradation assessment based on lifting wavelet packet decomposition and fuzzy c-means. Mech. Syst. Signal. Process. 24, 559–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2009.07.010 (2010).

Wang, B. et al. Rolling bearing performance degradative state recognition based on mathematical morphological fractal dimension and fuzzy center means. Acta Armamentarii36, 1982 (2015). https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=….

Cebeci, Z. & Yildiz, F. Comparison of k-means and fuzzy c-means algorithms on different cluster structures. J. Agric. Inf. 6, 26–37 (2015).

Pimentel, B. A. & de Souza, R. M. Multivariate fuzzy c-means algorithms with weighting. Neurocomputing 174, 946–965. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2015.10.021 (2016).

Lailiyah, S. & Hafiyusholeh, M. Perbandingan Antara metode K-means clustering Dengan Gath-Geva clustering. J. Mat. Mantik. 1, 26–37 (2016).

Yu, K., Lin, T. R. & Tan, J. W. A bearing fault diagnosis technique based on singular values of EEMD Spatial condition matrix and Gath-Geva clustering. Appl. Acoust. 121, 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apacoust.2017.01.021 (2017).

Li, Y. et al. Rolling element bearing performance degradation assessment using variational mode decomposition and Gath-Geva clustering time series segmentation. Int. J. Rotating Mach. 2017 (2598169). https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/2598169 (2017).

Rodriguez, A. & Laio, A. Clustering by fast search and find of density peaks. Science 344, 1492–1496. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1242072 (2014).

Xu, F. et al. A fault diagnosis method combined with ensemble empirical mode decomposition, base-scale entropy and clustering by fast search algorithm for roller bearings. J. Vibroeng. 18, 4472–4490. https://doi.org/10.21595/jve.2016.16940 (2016).

Xu, F. & Tse, P. W. Automatic roller bearings fault diagnosis using DSAE in deep learning and CFS algorithm. Soft Comput. 23, 5117–5128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-018-3173-2 (2019).

Baranidharan, B. et al. Group decision on rationalizing disease analysis using novel distance measure on pythagorean fuzziness. Complex. Intell. Syst. 10, 4373–4395. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40747-023-01298-8 (2024).

Bruckdorfer, R. E., Büttner, O. B. & Mau, G. Flavor, fun, and vitamins: consumers’ Lay beliefs about child-oriented food products. Appetite 205, 107773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2024.107773 (2024).

Bavadharani, B. et al. Selection of phase change material under uncertainty for waste heat recovery in diesel engine generator. J. Energy Storage. 108, 114982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2025.114982 (2025).

Baranidharan, B. et al. Assessing the sustainability of the prepandemic impact on fuzzy traveling sellers problem with a new fermatean fuzzy scoring function. Sustainability 14, 16560. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416560 (2023).

Nextoux, P. et al. PRONOSTIA: An experimental platform for bearings accelerated life test. IEEE Int. Conf. Progn. Health Manag. 1–6 (2012). (2012). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICPHM.2012.6299546

Acknowledgements

The first author and the corresponding author contributed equally. Financial support to complete this study was provided by the National Key Research and Development Program of China(NO.2023YFE0203200), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO.52205168, No. 52205575), the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (No. 2025 AFD376), and the Jingmen Science and Technology Burea (NO. 2024ZDYF004). Supports from the Fundamental Research Funds for the Jingchu University of Technology (NO. YY202444) are also appreciated.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shengwen Zhou: Methodology, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Li Zhang: Data curation, Validation, Visualization.XiaoMing Yang: Resources, Supervision.Fan Xu: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Validation.BaiGang Du: Supervision. Ruiping Luo: Formal analysis.Wenhui Zeng: Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, S., Zhang, L., Yang, X. et al. A method based on clustering fast search for bearing performance degradation assessment. Sci Rep 15, 17930 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01513-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01513-1