Abstract

Background Short interval intracortical inhibition (SICI) remains the most sensitive parameter to assess motor cortical function in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). While an initial value of SICI has been utilised to support a diagnosis of ALS, less is known about progression of change. Methods Motor cortex function was prospectively assessed in ALS patients, through serial threshold tracking transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) assessment over more than 12 months. Motor cortical potentials were recorded from the abductor pollicis brevis (APB). Demographic information and clinical variables were analysed. Results A cohort of 52 ALS patients (69.2% limb-onset disease; 47.2% right-side) were assigned to undergo longitudinal assessment of cortical motor function. Mean ALSFRS-R score at baseline was 39.5 ± 1.0 denoting relatively milder clinical deficits at study commencement. Cortical motor dysfunction was evident at baseline, with reduction in averaged SICI (p = 0.004) when compared to healthy controls. In terms of disease trajectory, ALS patients experienced a significant decline in averaged SICI overtime. When compared to initial assessment, averaged SICI was significantly reduced after 12 months (p = 0.004). There was no significant main effect of site of onset on averaged SICI (p = 0.78). The progressive change in averaged SICI was more robust in the dominant hemisphere, with the proportion of ALS patients who demonstrated a clinically abnormal averaged SICI value (< 5.5%) increasing by 50%, compared to 15.4% for the non-dominant hemisphere. Conclusion ALS patients demonstrate progressive cortical motor abnormalities, evident through longitudinal assessment. While SICI represents a diagnostic biomarker, the rate of decline in the present series is consistent with disease progression, suggesting a potential role to monitor the efficacy of therapeutic intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a relentlessly progressive and fatal neurodegenerative disease of the motor neurons1,2. While the exact pathophysiology of ALS remains unknown, mounting evidence suggests that hyperexcitability is closely linked to the disease pathophysiology3,4,5,6. Specifically, it has been postulated that hyperexcitability of the corticomotorneuronal networks may induce trans synaptic degeneration of the spinal and bulbar motor neurons by means of glutamate mediated excitotoxicity, potentially leading to accumulation and mislocalisation of the RNA/DNA binding protein Transactivase response DNA binding protein-43 (TDP-43) in the upper and lower motor neuronal compartments7.

In terms of mechanistic insights, post-mortem neuropathological and molecular studies have underlined several potential pathways that could induce the evolution of cortical hyperexcitability in ALS. These include degeneration of the parvalbumin positive inhibitory cortical interneurons, selective impairment of the excitatory amino acid transporter 2 and reduced expression of the GABAA receptors in the motor cortex8,9,10,11.

Longitudinal studies in pre-symptomatic carriers of genetic mutations linked to ALS previously established that cortical hyperexcitability developed months prior to the clinical onset of ALS, emphasising the potential role of altered cortical function in the pathogenesis of ALS12,13. Assessment of brain motor pathways using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), specifically the threshold-tracking method, has provided a non-invasive means of interrogation and assessment of cortical circuitry with high sensitivity and specificity14,15,16. Of the various parameters that estimate cortical motor function, short interval intracortical inhibition (SICI) induced through a paired pulse paradigm has been proven to be the most robust and reproducible biomarker of cortical excitability17. An averaged SICI value lower than 5.5% has been reported to distinguish ALS from mimic disorders with a sensitivity and specificity of ~ 70%, thereby potentially reducing diagnostic delays17. While SICI has utility as a diagnostic biomarker of ALS, there have been limited prospective studies examining the trajectory of changes in SICI over time. In particular, it is not known what proportion of ALS patients who do not demonstrate cortical hyperexcitability (indicated by an averaged SICI value over 5.5%) on initial assessment, will go on to develop hyperexcitability during the course of their disease. As such, the present study investigated progressive changes in averaged SICI and the evolution of cortical function through serial assessment of ALS patients.

Methodology

Patients

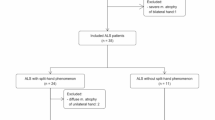

Prospective studies were undertaken with ALS patients who attended the Forefront Multidisciplinary MND clinic, Sydney, Australia. Patients diagnosed with ALS as per the Gold Coast criteria were eligible for inclusion in the study18. Patients were examined via clinical, neurophysiological and functional assessments conducted at their initial visit and followed up, prospectively, at 3–6 monthly intervals. All patients enrolled provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (Code of Ethics, World Medical Association). The research study was approved by South Eastern Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee, reference number 2021/ETH00559.

Clinical assessments

At initial assessment, patients underwent neurological examination and were categorised based on the site of onset of their motor presentation (limb or bulbar). Disease duration was recorded in months from symptom onset to the time of initial assessment. Functional disability was assessed using the Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale – Revised (ALSFRS-R) (range: 0–48), where lower scores indicate greater functional disability18. Cognitive assessments, using the Edinburgh Cognitive and Behavioural ALS Screen (ECAS) (range: 0–136; cognitive abnormality cut-off 105)19 and Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination (ACE-III) (range: 0–100; cognitive abnormality cut-off 88)20 scales were completed. For both of these cognitive assessments, higher scores indicate better cognitive performance.

Neurophysiological assessment

Patients underwent paired pulse threshold tracking TMS as described previously21. Briefly, A 90-mm circular coil was used to stimulate the primary motor cortex while the motor evoked potential (MEP) was recorded from the right and left abductor pollicis brevis (APB). This muscle was chosen due to its ease of accessibility, its common and early involvement in ALS and the availability of normative data22. For each assessment, the coil was applied over the hand area of the primary motor cortex in the contralateral hemisphere.

To assess cortical excitability, short interval intracortical inhibition (SICI) was measured using Magxite software23 as per the Sydney protocol24. The stimulus intensity required to produce a defined motor potential of 0.2 mv was determined and defined as the resting motor threshold (RMT). A subthreshold conditioning stimulus set at 70% of RMT preceded a test stimulus at interstimulus intervals (ISI) of 1 ms, 1.5 ms, 2 ms, 2.5 ms, 3 ms, 3.5 ms, 4 ms, 5 ms, and 7 ms and the change in conditioned stimulus intensity required to evoke the defined motor potential of 0.2 mV ± 20% was determined for each ISI and defined as SICI21. Averaged SICI was defined as the mean of SICI values obtained at each interstimulus interval from 1 ms to 7 ms. Previous studies have determined that SICI at the 1–7 ms interstimulus interval is reduced in people with ALS15,25.

Statistical analysis

Clinical and neurophysiological data for ALS patients were recorded, along with descriptive analyses of demographic data. All data were expressed as mean ± standard error (SE), group mean ± confidence interval (95% CI) or median and interquartile range (IQR). An averaged SICI of less than 5.5% at each time point was utilised as a diagnostic biomarker17. Results in ALS patients were compared with normative data previously established from a cohort of age-matched healthy controls from the same research clinic26,27. In this study we used single timepoint comparisons for control participants as intracortical inhibition has been shown to remain relatively stable with age in healthy individuals26. A Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was performed to assess the normality of the data. To determine the difference in the averaged SICI of healthy controls when compared to patients with ALS at their initial assessment, an independent samples Mann-Whitney U test was performed.

To address missing data, we used multiple imputation as implemented in IBM Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) (version 27.0). Imputations were conducted using the fully conditional specification method with 50 iterations per imputation. A total of 30 imputed datasets were generated under the assumption that data were missing at random. The imputation model included all variables used in the primary analyses. Pooled estimates across the imputed datasets were computed using Rubin’s rules. To examine change in averaged SICI overtime, we conducted mixed model analyses using the imputed data from SPSS with the mice package in R (version 4.4.2). A mixed model with a random intercept for participants and fixed effects for timepoint and onset was used. Diagnostic plots were examined and appeared acceptable. Pairwise comparisons were conducted using the main effects model to examine differences between timepoints (initial assessment, < 6 months post initial assessment, > 6 months post initial assessment, > 12 months post initial assessment) controlling for site of onset. P-values for the pairwise comparisons were adjusted using the Holm method. An interaction model was fitted to assess whether there was a significant interaction between timepoint and limb or bulbar onset.

To determine the change in proportion of patients with evidence of clinically significant cortical hyperexcitability (averaged SICI < 5.5%)17 overtime, a Cochran’s Q test was performed, with post-hoc pairwise comparisons determined using McNemar’s tests. Analyses were conducted on data from patients who completed all assessment timepoints. Independence of observations and nominal data were met for Cochran’s Q test.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Version 27.0) unless stated otherwise, where significance was specified as p < 0.05.

Results

Clinical features

A cohort of 52 ALS patients (55.8% male, mean age 62.1 ± 11.5 years) were recruited for initial assessment, a median of 14 months (IQR:12) from symptom onset (Table 1). Each patient underwent sequential assessment of cortical motor function. The majority of patients were prescribed oral Riluzole (96.2%, n = 50) throughout the study period. In terms of disability, the ALSFRS-R score at the initial TMS study was 39.5 ± 1.0 indicating enrolment of patients who were relatively early in the course of their disease, with mild clinical deficits. In terms of clinical phenotype, 69.2% of patients had limb-onset disease (n = 36), with the remaining patients diagnosed with bulbar-onset ALS. Cognitive assessments determined that the majority of patients assessed (61%, n = 22) had a ‘pure’ ALS phenotype without overlapping features of behavioural or cognitive dysfunction.

Cortical motor function

Cortical excitability in healthy control and ALS patients

When compared to age matched healthy controls, cortical dysfunction was evident in the motor cortex of patients in the ALS cohort, as indicated by a reduction in initial averaged SICI recorded from the APB (Healthy controls 10.6%, ALS: 6.3%, U = 1101.00, p = 0.004, Fig. 1).

Comparison of averaged SICI recorded from the APB between age-matched healthy controls and ALS patients at initial assessment (p = 0.004). Boxplots display the distribution of averaged SICI for each group. The boxes represent the IQR, the horizontal line within each box indicates the median, the x indicates the mean and whiskers denote the range excluding outliers. Individual data points are overlaid.

Progressive decline in averaged SICI recorded from the APB of patients with limb and bulbar onset ALS. Line plots depict the overall ALS cohort (solid line), limb-onset subgroup (dotted line), and bulbar-onset subgroup (dashed line) over four assessment timepoints: Initial, < 6 months, > 6 months, and > 12 months. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Progressive cortical dysfunction in ALS patients regardless of site of onset

In terms of disease trajectory, ALS patients experienced a significant decline in averaged SICI overtime. When compared to initial assessment, averaged SICI was significantly reduced after 12 months (β = −6.9, p = 0.004). Specifically, averaged SICI differed significantly from initial assessment by 6 months (β = −3.2, p = 0.02) declining to a value of −0.7%±4.5 [CI: −5.2,3.8] after twelve months following the initial assessment. There was no significant main effect of site of onset on averaged SICI (β = −0.7, p = 0.78).

The interaction between time of assessment and site of onset was not statistically significant (all p’s > 0.24), suggesting that the trajectory of averaged SICI change overtime does not differ by site of onset. Averaged SICI declined significantly after 6 months following initial assessment in patients with limb onset ALS, declining from 6.8%±3.2 [CI: 3.6,10.0] to 3.6%±3.3 [CI:0.3,6.9] (β = 8.8, p = 0.00002). Averaged SICI decline was also evident in patients with bulbar onset ALS, declining from 5.2%±4.8 [CI: 0.4,10.0] to 2.2%±4.9 [CI: −2.7,7.0] (β = 5.33, p = 0.15), however, this did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 2).

Clinically significant cortical hyperexcitability with disease progression

In terms of the distribution of cortical motor dysfunction across the ALS cohort, an increased proportion of patients developed evidence of clinically significant cortical hyperexcitability (averaged SICI <5.5%17) in the dominant hemisphere with disease progression (R APB: initial assessment = 42.6%, <6 months = 64.3%, >6 months = 85.7%, >12 months = 92.6%)(Q =12.857, p=0.005, Fig.3a). Specifically, the proportion of ALS patients who demonstrated a clinically abnormal averaged SICI value increased over the course of the assessment period by 50%. However, the proportion of patients with an averaged SICI <5.5% did not differ significantly with disease progression for the non-dominant hemisphere (L APB: initial assessment = 61.5%, <6 months = 46.2%, >6 months = 46.2%, >12 months = 76.9%) (Q=6.000, p=0.112, Fig. 3b.).

Discussion

The present study has established that cortical motor dysfunction, reflected by reduction in averaged SICI, becomes increasingly abnormal during the course of ALS. This is consistent with consensus diagnostic criteria for ALS, which define ALS as a progressive disorder, based on clinical history or neurological examination at clinical follow-up18. Smaller studies which examined changes in cortical function of ALS patients, demonstrated similar reductions in averaged SICI over a shorter follow-up period of ~ 3 months28. Results from the present study suggest that the identification of a progressive evolution of cortico-motorneuronal hyperexcitability becomes more apparent with disease evolution in ALS, and evident in a greater proportion of patients with time from diagnosis. This decline in averaged SICI was evident in patient with both limb and bulbar onset. Though this did not reach statistical significance for the bulbar group, this was likely due to the smaller sample size which was representative of the phenotype distribution in the ALS population. Progressive change (reduction) in SICI over a period of more than 12 months further supports consideration for the assessment of motor cortical function as a diagnostic and disease-progression biomarker in ALS. Interpreting such dynamic change, it is important to note, however, that cortical excitability is influenced by the stage of disease at the time of testing, as well as disease progression rate29. As motor neurons degenerate and die, it could be further accepted that individual cells may become hypoexcitable30, or fail to fire, although such activity may not be appreciated in averaged values of SICI. Assessment of central motor pathways in patients is not yet such a precise technique, and the technology does not allow clinicians to differentiate change at an individual cellular level. Regardless, future studies involving larger sample sizes may promote an improved patient stratification based on time of symptom onset and disease progression, further elucidating the trajectory of cortical excitability and its potential prognostic insights.

While dysfunction of the motor cortex appears to be critically linked to the pathophysiology in ALS, the precise mechanism remains less clearly understood. Neuropathology reports that degeneration of cortical inhibitory interneurons may contribute to cortical hyperexcitability in ALS31, with identification of structural changes within cortical interneurons in ALS mouse models providing further supportive evidence32,33. Separate to functional approaches, neuroimaging profiles of ALS patients have concluded that progressive loss of motor cortex thickness is a more sensitive measure than the pyramidal tract fibre density in ALS patients with upper motor neuron (UMN) dysfunction, perhaps providing further indirect evidence that degeneration of pathways within the motor cortex may have a significant effect on disease evolution in ALS34.

Given that degeneration of inhibitory cortical circuits develops as a longitudinal process in ALS28,35, serial assessment of motor cortical function could provide a functional marker of disease progression, while at the same time may assist in distinguishing ALS from mimic disorders, with greater sensitivity and specificity. Obtaining a SICI trajectory over a period of time in ALS patients via longitudinal studies, may further enhance a more precise characterisation of disease evolution in ALS. Specifically, longitudinal determination of the rate of SICI decline may establish a precise biomarker to determine potential benefits of therapeutic intervention, particularly useful for those ALS patients in whom absolute SICI values remain above the diagnostic cutoff of 5.5%34,36. Serial TMS studies analysing the change in cortical function may also prove useful in monitoring subclinical disease progression in a subset of patients who may be considered to be in a plateau phase of the disease.

Imbalance of inhibitory and facilitatory pathways likely contributes to cortical hyperexcitability and disease pathogenesis in ALS37,38,39. This view is further supported by the present study which has identified sustained and continuous reduction of SICI in ALS patients, despite regular doses of Riluzole, an antagonist of glutamate mediated excitotoxicity. Riluzole has a modest effect on cortical function, with a transient, partial normalisation of SICI that appears to last for 8–12 weeks40,41. Such a result correlates with the clinical efficacy of Riluzole, estimated to slow disease progression for 3–6 months5,42. Therapeutic intervention targeting other potential mechanisms involved in cortical dysfunction in ALS may exert a greater impact on the disease.

In terms of explaining the asymmetry of results recorded from the dominant and non-dominant hemisphere in the present series, focal onset of weakness is typical in ALS. As initially recorded in the nineteenth century by Gowers in his textbook of neurology, he perceptively noted that from the part of the limb first affected, that the disease spreads to other parts of the same limb, and then to similar regions in the corresponding limb43. This process has often been linked to disruption and degeneration of the corticomotorneuronal system44. This apparent asymmetry most likely begins as part of an evolution of the human motor system, with synaptic connections emerging within the corticomotoneuronal system, driven by needs related to motor processing, and likely underlies the development of cerebral dominance and laterality45,46. Motor asymmetry becomes evident in handedness, which manifests early in development of the neonatal brain47. Physiological studies using TMS have established that the dominant hand has a shorter cortical silent period, which has been attributed to a relative withdrawal of corticospinal input to spinal motoneurons, and perhaps a relative asymmetry in cortical inhibitory pathways48. Separate to functional changes in motor pathways, the asymmetrical spread of disease that appears evident in ALS may also suggest that the disease spreading mechanism, as yet to be defined, may reflect anatomical organisation of human motor networks49. As such, it seems likely that these factors contributed to the difference in the present results recorded from the dominant and non-dominant hemispheres in ALS patients.

Findings from the present series illustrate that the progressive change in SICI is more robust in the dominant hemisphere, with the proportion of ALS patients who demonstrated a clinically abnormal averaged SICI value (< 5.5%) increasing by 50% compared to 15.4% for the non-dominant hemisphere. Several clinical studies have suggested the dominant upper limb as the preferential site of ALS onset with one study demonstrating the objective asymmetry in the clinical (UMN) signs between the dominant and non-dominant upper limbs with maximum UMN dysfunction seen in the dominant hand50,51,52,53. Our series provides electrophysiological support to the conception of limb dominance influencing the clinical onset site in ALS. The potential mechanisms of that underlie the progressive decline in SICI across the dominant hemisphere remain relatively unexplored, and may potentially reflect secondary changes that relate to overuse of the dominant limb, rather than direct changes in excitability arising from involvement of the dominant hemisphere. Our findings demonstrate that serial neurophysiological assessment of the dominant hemisphere provides a more sensitive measure of cortical function in comparison to the non-dominant hemisphere52.

Another neurophysiological measure of cortical excitability that has been shown to be significantly affected in ALS is short interval intracortical facilitation (SICF)39. Similar to SICI, SICF is also evaluated through the paired pulse TMS technique except that a suprathreshold preconditioning pulse is used instead of a subthreshold stimulus54,55,56. In ALS, SICF has been shown to be consistently elevated in patients with reduced SICI, suggesting simultaneous impaired cortical inhibitory mechanisms as well as overactive excitatory pathways however, longitudinal SICF change in ALS patients is yet to be determined39. Although the exact cause of increased SICF and the resultant index of excitation in ALS remains to be elucidated, there is some evidence that this is not mediated through glutamatergic pathways57. Future studies monitoring both SICI and SICF longitudinally may provide greater insight into the pathophysiology of disease progress, hence guiding the therapeutic targets in ALS.

Limitations

In our study cohort, almost all patients were prescribed Riluzole, which could have impacted the natural evolution of the disease, and hence our overall results. It is accepted that Riluzole may induce a transient pseudo-normalisation of SICI, such that results from the present study may underestimate the overall effect of ALS on cortical excitability parameters38. However, given that Riluzole delays ALS disease progression and is the only approved treatment in Australia, it would not be feasible to delay or prevent standard of care treatment for our study. Conversely, the limited number of patients not prescribed Riluzole would not have statistical power for comparison. It would be useful for future studies to stratify patients based on Riluzole dosage and treatment duration to determine the impact these factors may have on SICI decline.

As our cohort was generally earlier in their disease course with mild clinical deficits, it would be interesting for future studies to monitor longitudinal functional decline, using the ALSFRS-R, to determine the relationship between SICI decline in patients with ALS and their disease progression at a functional level. Furthermore, evaluating clinical upper and lower motor neuron features alongside measures of cortical excitability at the time of TMS assessment may offer a deeper insight into the relationship between clinical motor neuron involvement and cortical hyperexcitability in ALS, from both pathophysiological and functional perspectives. In addition to functional and clinical markers of decline, biomarkers indicative of neuronal and glial damage such as neurofilament light chain (NFl) and Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP), may provide supportive mechanistic insights58,59,60.

A larger longitudinal study investigating several parameters of cortical function alongside SICI such as SICF, Cortical Silent Period (CSP), RMT, MEP, MEP/Compound Muscle Action Potential (CMAP) ratio, and index of cortical excitation among patients with ALS and a control group may be useful in establishing a more complete understanding of ALS disease mechanisms, particularly in terms of the evolution of cortical function with disease progression. However, each of these added parameters are largely research related, and serve to increase the duration for each study. In contrast, the purpose of the present study was to provide helpful data for clinical diagnostic purposes, to follow the evolution of cortical hyperexcitability with disease duration. Additionally, it would be useful to validate the findings of our current study in alternative muscle groups, specifically in the lower limb, such as tibialis anterior.

Conclusion

The present study highlights that cortical dysfunction becomes more apparent with disease progression in ALS. Specifically, the present series suggests that SICI has utility as a biomarker for longitudinal assessment of cortical motor function and disease involvement in ALS. Separately, the present series suggests that a second assessment of cortical motor function adds diagnostic potential for a cohort of patients with clinically suspected ALS, in whom the initial SICI value remains above 5.5%.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACE:

-

III–Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination

- ALS:

-

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- ALSFRS:

-

R–Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis functional rating scale–Revised

- APB:

-

Abductor pollicis brevis

- CI:

-

95% Confidence Interval

- CMAP:

-

Compound Muscle Action Potential

- CSP:

-

Cortical Silent Period

- ECAS:

-

Edinburgh Cognitive and Behavioral ALS Screen

- GABA:

-

Gamma–amminobutyric acid

- GFAP:

-

Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein

- IQR:

-

Interquartile Range

- ISI:

-

Interstimulus Intervals

- MEP:

-

Motor Evoked Potential

- NFl:

-

Neurofilament Light Chain

- RMT:

-

Resting Motor Threshold

- SE:

-

Standard Error

- SICF:

-

Short interval intracortical facilitation

- SICI:

-

Short interval intracortical inhibition

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for Social Science

- TDP:

-

43–Transactivase response (TAR) DNA binding protein–43

- TMS:

-

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

- UMN:

-

Upper Motor Neuron

References

Vucic, S., Rothstein, J. D. & Kiernan, M. C. Advances in treating amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: insights from pathophysiological studies. Trends Neurosci. 37, 433–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2014.05.006 (2014).

Kiernan, M. C. et al. Improving clinical trial outcomes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Reviews Neurol. 17, 104–118. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-020-00434-z (2021).

Rothstein, J. D., Jin, L., Dykes-Hoberg, M. & Kuncl, R. W. Chronic Inhibition of glutamate uptake produces a model of slow neurotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 90, 6591–6595. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.90.14.6591 (1993).

Eisen, A., Kim, S. & Pant, B. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS): a phylogenetic disease of the corticomotoneuron? Muscle Nerve. 15, 219–224. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.880150215 (1992).

Kiernan, M. C. et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet 377, 942–955. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(10)61156-7 (2011).

Vucic, S., Ziemann, U., Eisen, A., Hallett, M. & Kiernan, M. C. Transcranial magnetic stimulation and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: pathophysiological insights. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 84, 1161–1170. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2012-304019 (2013).

Reale, L. A. et al. Pathologically mislocalised TDP-43 in upper motor neurons causes a die-forward spread of ALS-like pathogenic changes throughout the mouse corticomotor system. Prog Neurobiol. 226, 102449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2023.102449 (2023).

Nihei, K., McKee, A. C. & Kowall, N. W. Patterns of neuronal degeneration in the motor cortex of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. Acta Neuropathol. 86, 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00454899 (1993).

Petri, S. et al. GABA(A)-receptor mRNA expression in the prefrontal and Temporal cortex of ALS patients. J. Neurol. Sci. 250, 124–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2006.08.005 (2006).

Petri, S. et al. Distribution of GABAA receptor mRNA in the motor cortex of ALS patients. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 62, 1041–1051. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnen/62.10.1041 (2003).

Rothstein, J. D., Van Kammen, M., Levey, A. I., Martin, L. J. & Kuncl, R. W. Selective loss of glial glutamate transporter GLT-1 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 38, 73–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.410380114 (1995).

Brunet, A., Stuart-Lopez, G., Burg, T., Scekic-Zahirovic, J. & Rouaux, C. Cortical circuit dysfunction as a potential driver of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Front. Neurosci. 14, 363. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2020.00363 (2020).

Vucic, S., Nicholson, G. A. & Kiernan, M. C. Cortical hyperexcitability May precede the onset of Familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 131, 1540–1550. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awn071 (2008).

Vucic, S. et al. Utility of threshold tracking transcranial magnetic stimulation in ALS. Clin. Neurophysiol. Pract. 3, 164–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnp.2018.10.002 (2018).

Vucic, S. & Kiernan, M. C. Novel threshold tracking techniques suggest that cortical hyperexcitability is an early feature of motor neuron disease. Brain 129, 2436–2446. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awl172 (2006).

Menon, P. et al. Sensitivity and specificity of threshold tracking transcranial magnetic stimulation for diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a prospective study. Lancet Neurol. 14, 478–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00014-9 (2015).

Vucic, S., Cheah, B. C., Yiannikas, C. & Kiernan, M. C. Cortical excitability distinguishes ALS from mimic disorders. Clin. Neurophysiol. 122, 1860–1866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2010.12.062 (2011).

Shefner, J. M. et al. A proposal for new diagnostic criteria for ALS. Clin. Neurophysiol. 131, 1975–1978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2020.04.005 (2020).

Abrahams, S., Newton, J., Niven, E., Foley, J. & Bak, T. H. Screening for cognition and behaviour changes in ALS. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Frontotemporal Degener. 15, 9–14. https://doi.org/10.3109/21678421.2013.805784 (2014).

Mathuranath, P. S., Nestor, P. J., Berrios, G. E., Rakowicz, W. & Hodges, J. R. A brief cognitive test battery to differentiate Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 55, 1613–1620. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000434309.85312.19 (2000).

Vucic, S., Howells, J., Trevillion, L. & Kiernan, M. C. Assessment of cortical excitability using threshold tracking techniques. Muscle Nerve. 33, 477–486. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.20481 (2006).

Dharmadasa, T. et al. The effect of coil type and limb dominance in the assessment of lower-limb motor cortex excitability using TMS. Neurosci. Lett. 699, 84–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2019.01.050 (2019).

Vucic, S. et al. Neurophysiological assessment of cortical motor function: A direct comparison of methodologies. Clin. Neurophysiol. 170, 14–21 (2025).

Tankisi, H. et al. Short-interval intracortical Inhibition as a function of inter-stimulus interval: three methods compared. Brain Stimul. 14, 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2020.11.002 (2021).

Matamala, J. M. et al. Inter-session reliability of short-interval intracortical Inhibition measured by threshold tracking TMS. Neurosci. Lett. 674, 18–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2018.02.065 (2018).

Shibuya, K. et al. Threshold tracking transcranial magnetic stimulation: effects of age and gender on motor cortical function. Clin. Neurophysiol. 127, 2355–2361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2016.03.009 (2016).

Shibuya, K. et al. Laterality of motor cortical function measured by transcranial magnetic stimulation threshold tracking. Muscle Nerve. 55, 424–427. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.25372 (2017).

Shibuya, K. et al. The evolution of motor cortical dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clin. Neurophysiol. 128, 1075–1082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2017.03.004 (2017).

Di Lazzaro, V. et al. Novel approaches to motoneuron disease/als treatment using non-invasive brain and spinal stimulation: IFCN handbook chapter. Clin. Neurophysiol. 158, 114–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2023.12.012 (2024).

Marchand-Pauvert, V. et al. Absence of hyperexcitability of spinal motoneurons in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Physiol. 597, 5445–5467. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP278117 (2019).

Maekawa, S. et al. Cortical selective vulnerability in motor neuron disease: a morphometric study. Brain 127, 1237–1251. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awh132 (2004).

Ozdinler, P. H. et al. Corticospinal motor neurons and related subcerebral projection neurons undergo early and specific neurodegeneration in hSOD1G⁹³A Transgenic ALS mice. J. Neurosci. 31, 4166–4177. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.4184-10.2011 (2011).

Clark, R. M., Blizzard, C. A., Young, K. M., King, A. E. & Dickson, T. C. Calretinin and neuropeptide Y interneurons are differentially altered in the motor cortex of the SOD1G93A mouse model of ALS. Sci. Rep. 7, 44461. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44461 (2017).

Nitert, A. D. et al. Sensitivity of brain MRI and neurological examination for detection of upper motor neurone degeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 93, 82–92. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2021-327269 (2022).

Menon, P. et al. Cortical hyperexcitability evolves with disease progression in ALS. Ann. Clin. Transl Neurol. 7, 733–741. https://doi.org/10.1002/acn3.51039 (2020).

Wainger, B. J. et al. Effect of ezogabine on cortical and spinal motor neuron excitability in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 78, 186–196. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.4300 (2021).

Pieri, M., Carunchio, I., Curcio, L., Mercuri, N. B. & Zona, C. Increased persistent sodium current determines cortical hyperexcitability in a genetic model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Exp. Neurol. 215, 368–379 (2009).

Zhang, W. et al. Hyperactive somatostatin interneurons contribute to excitotoxicity in neurodegenerative disorders. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 557–559. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4257 (2016).

Van den Bos, M. A. J. et al. Imbalance of cortical facilitatory and inhibitory circuits underlies hyperexcitability in ALS. Neurology 91, e1669–e1676. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000006438 (2018).

Vucic, S. et al. Riluzole exerts central and peripheral modulating effects in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 136, 1361–1370. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awt085 (2013).

Geevasinga, N. et al. Riluzole exerts transient modulating effects on cortical and axonal hyperexcitability in ALS. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Frontotemporal Degener. 17, 580–588. https://doi.org/10.1080/21678421.2016.1188961 (2016).

Bensimon, G., Lacomblez, L. & Meininger, V. A. Controlled trial of riluzole in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 330, 585–591. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199403033300901 (1994).

Gowers, W. R. A manual of diseases of the nervous system. Vol. 1 (J. & A. Churchill, 1886–1888).

Eisen, A., Vucic, S. & Kiernan, M. C. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis represents corticomotoneuronal system failure. Muscle Nerve. 71, 499–511. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.28290 (2025).

Henderson, R. D., Garton, F. C., Kiernan, M. C., Turner, M. R. & Eisen, A. Human cerebral evolution and the clinical syndrome of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 90, 570, doi:10.1136/jnnp-2017-317245 (2019).

Lubben, N., Ensink, E., Coetzee, G. A. & Labrie, V. The enigma and implications of brain hemispheric asymmetry in neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Commun. 3 https://doi.org/10.1093/braincomms/fcab211 (2021).

Kiernan, M. C., Ziemann, U. & Eisen, A. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: origins traced to impaired balance between neural excitation and Inhibition in the neonatal period. Muscle Nerve. 60, 232–235. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.26617 (2019).

Priori, A. et al. Human handedness and asymmetry of the motor cortical silent period. Exp. Brain Res. 128, 390–396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002210050859 (1999).

Ludolph, A. C. et al. Pattern of paresis in ALS is consistent with the physiology of the corticomotoneuronal projections to different muscle groups. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 91, 991–998 (2020).

Ravits, J., Paul, P. & Jorg, C. Focality of upper and lower motor neuron degeneration at the clinical onset of ALS. Neurology 68, 1571–1575. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000260965.20021.47 (2007).

Turner, M. R. et al. Concordance between site of onset and limb dominance in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 82, 853–854. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2010.208413 (2011).

Devine, M. S., Kiernan, M. C., Heggie, S., McCombe, P. A. & Henderson, R. D. Study of motor asymmetry in ALS indicates an effect of limb dominance on onset and spread of weakness, and an important role for upper motor neurons. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Frontotemporal Degener. 15, 481–487. https://doi.org/10.3109/21678421.2014.906617 (2014).

Eisen, A., Turner, M. R. & Lemon, R. Tools and talk: an evolutionary perspective on the functional deficits associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve. 49, 469–477. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.24132 (2014).

Ziemann, U. et al. Demonstration of facilitatory I wave interaction in the human motor cortex by paired transcranial magnetic stimulation. J. Physiol. 511 (Pt 1), 181–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.181bi.x (1998).

Hanajima, R. et al. Mechanisms of intracortical I-wave facilitation elicited with paired-pulse magnetic stimulation in humans. J. Physiol. 538, 253–261. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013094 (2002).

Van den Bos, M. A. J. et al. Physiological processes underlying short interval intracortical facilitation in the human motor cortex. Front. Neurosci. 12, 240. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.00240 (2018).

Ziemann, U., Tergau, F., Wischer, S., Hildebrandt, J. & Paulus, W. Pharmacological control of facilitatory I-wave interaction in the human motor cortex. A paired transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 109, 321–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0924-980x(98)00023-x (1998).

McCluskey, G. et al. Serum neurofilaments in motor neuron disease and their utility in differentiating ALS, PMA and PLS. Life (Basel). 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/life13061301 (2023).

Benninger, F., Glat, M. J., Offen, D. & Steiner, I. Glial fibrillary acidic protein as a marker of astrocytic activation in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Clin. Neurosci. 26, 75–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2015.10.008 (2016).

Rothstein, J. D., Martin, L. J. & Kuncl, R. W. Decreased glutamate transport by the brain and spinal cord in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 326, 1464–1468. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199205283262204 (1992).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DK and DLT contributed equally as co-first authors. DK and MCK conceived the study. DK, SP and JA collected the data and drafted the manuscript. DK, DLT and HCT analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. SV drafted the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and have given final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Krishnan, D., Talbot, DL., Ashhurst, J.F. et al. Longitudinal assessment of cortical motor function in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Sci Rep 15, 16978 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01570-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01570-6