Abstract

The objective of this study was to assess the toxicity of the insecticide esfenvalerate in Allium cepa, employing a multifaceted methodology. For this purpose, A. cepa bulbs were organized into four groups, one of which served as the control. The control group was exposed to tap water, while the remaining three groups were exposed to esfenvalerate at concentrations of 0.33 mg/L, 0.64 mg/L and 0.98 mg/L, respectively. The application of the highest dose of 0.98 mg/L esfenvalerate resulted in a significant decrease in physiological parameters, including a 51% reduction in rooting percentage, an 85.3% decrease in root elongation, and a 54.3% decrease in weight gain (p < 0.05). In the esfenvalerate-treated group (0.98 mg/L), a 45.7% decrease in mitotic index was observed, while a significant increase in chromosomal aberrations and micronucleus formation was observed compared to the control group (p < 0.05). The most frequently observed chromosomal abnormalities due to esfenvalerate were sticky chromosome, vagrant chromosome, fragment, unequal distribution of chromatin, bridge, vacuolated nucleus, reverse polarization and multipolar anaphase. Insecticide application could significantly increase the percentage of DNA tails up to 48.3%, as determined by the Comet test (p < 0.05). Exposure to 0.98 mg/L esfenvalerate increased malondialdehyde level (2.75-fold), proline level (1.96-fold), superoxide dismutase activity (1.35-fold), and catalase activity (1.69-fold) while reducing chlorophyll a level (58.18%) and chlorophyll b level (70.35%) (p < 0.05). Molecular docking analysis revealed that esfenvalerate can interact with tubulins, DNA topoisomerases, glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase, protochlorophyllide reductase and DNA molecules. Epidermis and cortex cell damages, cortex cell wall thickening, material accumulation in cortex cells and flattened cell nucleus were recorded as meristematic cell damages due to esfenvalerate. The toxicological profile of esfenvalerate on A. cepa exhibited dose dependence. While esfenvalerate-induced oxidative stress is the most probable cause of toxicity, direct interaction with DNA and other molecules that play a crucial role in maintaining cell integrity may also be among the mechanisms of toxicity. The study’s findings emphasize that esfenvalerate poses a risk to non-target organisms, underscoring the need for a reassessment of its regulations and further research into its toxicity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The term ‘ecosystem’ is defined as a complex system comprising biotic and abiotic components that interact to form a dynamic circle of life. Biotic elements include flora, fauna and other living organisms, while abiotic factors encompass environmental conditions and other non-living elements1. The widespread and improper use of pesticides in agricultural practices has emerged as an important contributor to chemical pollution of the entire ecosystem2.

Synthetic pyrethroids represent over 30% of insecticides employed in pesticide applications due to their photostable, high insecticidal activity, broad spectrum, and low toxicity to mammals, birds, and plants3. The synthesis of pyrethroids, which are considered highly effective contact pesticides, was achieved by modifying the properties of pyrethrin, a natural insecticide derived from the flowers of Pyrethrum species4. This class of insecticides bind to the sodium channel, thereby paralyzing insects. Another mechanism of action is the alteration of the membrane potential in nerve cells, which results in hyperexcitability with abnormal stability5. The contamination of the environment by synthetic pyrethroids may result from the application of these chemicals via airborne and ground-based methods, as well as from agricultural and urban runoff6.

Esfenvalerate [(S)-Cyano(3-phenoxyphenyl)methyl (2S)-2-(4-chlorophenyl)-3-methylbutanoate], a pyrethroid insecticide that is widely utilized in agricultural, housing and public health protection applications, is the most active enantiomer of fenvalerate7. The action of esfenvalerate has the capacity to induce alterations in the transmission of impulses along the axons of nerve cells. This process is achieved by the inactivation of sodium and calcium channels within the membranes of nerves8. The efficacy of the compound in living cells is attributable to its rapid incorporation into biological membranes and tissues, a process facilitated by its lipophilic nature9. Despite the efficacy of esfenvalerate on insect infestations caused by cockroaches, flies, and locusts, as well as other insect species, its toxicological impact on non-target species is a major concern8. Indeed, the non-target earthworm Eisenia fetida was found to be four times more susceptible to the toxic effects of esfenvalerate than fenvalerate, particularly through the induction of oxidative stress7. In Melanotaenia fluviatilis, another unintentional model organism, a linear relationship was identified between esfenvalerate exposure duration and acute toxicity10. Furthermore, the genotoxicity of esfenvalerate was evidenced by the occurrence of DNA damage and chromosomal abnormalities in albino rats2.

Plant models are frequently employed in toxicity studies to monitor physiological and anatomical abnormalities, DNA damage, chromosomal aberrations and imbalances in oxidative stress parameters, due to the presence of pollutants such as pesticides11,12. The World Health Organization, the United States Environmental Protection Agency, and the United Nations Environment Programme have all authorized the use of Allium cepa as a model plant in bioassays. This plant is an optimal subject for cytogenetic studies due to its rapid proliferation in root meristem cells, the presence of large chromosomes (2n = 16) that facilitate the detection of abnormalities, and the fact that no ethical approval is required13. The high correlation of the Allium test with mammalian toxicity test systems should also be considered14. In recent years, molecular docking studies have gained widespread acceptance as a tool for predicting the molecular mechanisms of cytotoxicity and genotoxicity revealed by the Allium test15. This in silico approach enables the assessment of potential interactions between the tested chemical and biological molecules16.

Although esfenvalerate is a hazardous pesticide widely used today, there are not enough studies investigating its toxic effects on non-target species, including humans. The absence of data hinders the capacity to estimate the impact on human health and the environment, as well as obstructing effective planning for application in agriculture.

In order to close this significant knowledge gap, there was a need to investigate the extent and mechanism of the toxic effect of esfenvalerate on non-target organisms using a recognized model and a widely cultivated agricultural plant (A. cepa).The goal of this study was to examine the potential toxicity of esfenvalerate insecticide in A. cepa from a variety of perspectives. For this purpose, physiological (rooting percentage, root elongation, weight gain) and biochemical changes [superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) enzyme activities, proline, malondialdehyde (MDA) and chlorophyll contents] and genotoxic changes [mitotic index (MI), Comet test-DNA tail percentage, micronucleus (MN) formation and chromosomal aberration (CAs) frequencies] that may be induced by esfenvalerate exposure were investigated. The effects of esfenvalerate on meristematic tissue were investigated through the microscopic examination of sections taken from the root tips. Molecular docking analysis was performed to predict the interactions of esfenvalerate molecule with tubulins, DNA topoisomerases, glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase, protochlorophyllide reductase and DNA molecules.

Materials and methods

Materials

Allium cepa bulbs utilized as test organisms for this study were procured from a local grocery store in Giresun, Turkey. The esfenvalerate chemical substance with the CAS Registry Number 66230-04-4 was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Corporation (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). The chemicals utilized in the experimental process were categorized as analytical-grade.

Experimental procedure

Bulbs of similar size and health condition were selected to ensure the most accurate comparison. The dosage of esfenvalerate was determined on the basis of the residue doses observed in plants17. In order to determine the toxicity of esfenvalerate on A. cepa, a series of treatments containing 0 mg/L (control) esfenvalerate, 0.33 mg/L esfenvalerate (ESF 1), 0.64 mg/L esfenvalerate (ESF 2) and 0.98 mg/L esfenvalerate (ESF 3) were applied to four groups of fifty bulbs each. During the preparation of all solutions, tap water was used to mimic field conditions and to minimize the osmotic pressure difference. For each experimental group, fifty bulbs were placed in glass beakers, with their disc-stem touching the relevant solution. The bulbs were rooted for a total of three days in an environment that was completely dark, with a constant temperature of 23 ± 1 °C, and the solutions were refreshed on a daily basis. The same conditions were maintained over six days to estimate chlorophyll pigments18.

Analysis of alterations in growth

At the end of the third day of treatments, the length adventitious roots of the harvested bulbs were measured with an electronic caliper. Bulbs with root length exceeding 10 mm were considered rooted to compute rooting percentage. The difference between the weights of the onions before and after the treatment was determined by precision scale.

Analysis of alterations in genotoxicity indicators

In order to evaluate the cytotoxic impact of esfenvalerate, the alterations in mitotic index (MI), chromosomal aberrations (CAs) and micronucleus (MN) frequencies in the root tips of A. cepa were monitored using the method of Staykova et al.19 For this purpose, root tip preparations were prepared and analyzed in detail. Roots of harvested onions were gently rinsed with distilled water and 1–2 cm segments were fixed in Clarke’s solution (glacial acetic acid/ethanol = 3:1) and washed once more with distilled water. The fixed root tips were then hydrolyzed in 1 N HCl at 60 °C for 13 min. Following hydrolysis, another wash with distilled water was performed and then the samples were stained with acetocarmine (1%) for 24 h. At the end of the staining process, preparations were prepared by the routine pumpkin preparation procedure and examined by microscope (IM-450, IRMECO) with the help of a drop of 45% acetic acid solution. The method of diagnosing the MN by differentiating it from the nucleus was based on the criteria proposed by Fenech et al.20 According to these criteria, the diameter of the MN should be 1/3 of the diameter of the main nucleus, both formations should be stained in the same way, and the MN should be separated from the main nucleus by a clear border. A total of 1,000 cells were analyzed for each group to evaluate the frequency of MN and CA. MI value for each group was determined by counting a total of 10,000 cells and using Eq. (1).

Comet Assay

The comet analysis methodology21 was also employed to determine the extent of damage caused by the Esfenvalerate pesticide to the genetic material of A. cepa. To obtain the required nuclear suspension for the Comet Assay, root tip samples were gently crushed in 400 mM Tris-buffer in an ice bath. A volume of 40 μL of nuclear suspension was added to each group, together with an equal volume of 1% low melting point agarose (LMPA) on slides pre-coated with normal melting point agarose (NMPA). Samples were placed in a horizontal gel electrophoresis tank containing 1 mM Na₂EDTA and 300 mM NaOH (pH > 13), left for 15 min and then run at 4 °C and 0.7 V/cm (20 V and 300 mA) for 20 min. After electrophoresis, the slides were stained with ethidium bromide for five min. The stained slides were then treated with tris-buffer to facilitate photography using fluorescence microscopy. The DNA ratios (%) of the head and tail sections of the comets were determined using CometScore 2.0.0.38 software (Tritek Corp., Sumerduck, VA, USA). In line with the quantitative classification proposed by Pereira et al.22, the tail DNA percentages obtained from the software were evaluated as follows: a value of ≤ 5% represents no or minor damage, 5–20% represents low damage, 20–40% represents moderate damage, 40–75% represents high damage, and a value of 75% is represents severe damage. Moreover, the degree of DNA damage observed in the comet images was assessed in accordance with the visual scale proposed by Jayawardena et al.23.

Analysis of alterations in biochemical indicators

The biochemical analyses were carried out in triplicate to allow for statistical evaluation. Chlorophyll content analyses were carried out on leaves harvested at the end of the sixth day, while all other analyses were carried out on roots harvested at the end of the third day. To determine chlorophyll a and b contents, 0.1 g of leaves were crushed in 2.5 mL acetone (80%) and incubated in the dark for one week. After the mixture was filtered, 2.5 mL acetone (80%) was added and mixed thoroughly. The resulting 5 mL solution was then centrifuged at 3000 rpm and the absorbance of the supernatant was measured spectrophotometrically at both 645 nm and 663 nm. To calculate chlorophyll contents, the formulas (Eqs. 2 and 3) suggested by Witham et al.24 were applied:

A663: absorbance value of the supernatant at 663 nm, A645: absorbance value of the supernatant at 663, V: final volume (mL) and W: weight of fresh leaf (g).

In order to analyze the concentration of proline in A. cepa root tissue, a sample of 0.25 g of root tissue was homogenized with 5 mL of aqueous sulfosalicylic acid (3%)25. Following filtration of the homogenate, the filtrate was combined with equal volumes of acid-ninhydrin and glacial acetic acid. The resulting mixture was allowed to react in a hot water bath at 100 °C for one hour. After the reaction was terminated by cooling the mixture in an ice bath for two minutes, 2 mL toluene was added to the mixture and vortex mixed. The supernatant was then collected and the absorbance was determined using a spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 520 nm, in comparison to a control sample of pure toluene. Equation (4) and a standard curve were used to quantify the proline concentration of fresh weight of samples (FW).

The accumulation of lipid peroxidation MDA caused by esfenvalarate-induced oxidative stress was determined by the method proposed by Ünyayar et al.26. A 0.5 g sample of A. cepa root was homogenized with 1 mL of trichloroacetic acid (TCA) (5%) and the obtained homogenate was further processed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 15 min. The supernatant was combined with equal volumes of 20% TCA and 0.5% thiobarbituric acid, and then incubated at 100 °C for 20 min in a hot water bath. The reaction in the mixture was terminated by placing the tubes in an ice bath, subsequently the mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min. The absorbance of the mixture was then measured using spectrophotometry at 532 nm.

The determination of SOD and CAT enzyme activities was conducted using the methodology described by Zou et al.27. In accordance with this procedure, 1 g of fresh root tip was mechanically homogenized with 10 mL of monosodium phosphate buffer (50 mM/pH 7.8). The enzyme rich supernatant was obtained by centrifuging the homogenate at 10,000 rpm for 25 min and was utilized for subsequent analyses.

The measurement of SOD enzyme activity was conducted by combining 0.01 mL of the enzyme extract with a total of 3 ml of reaction mixture, comprising monosodium phosphate buffer, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and distilled water28. To initiate the reaction, the mixture was placed in transparent glass tubes in front of a 30 W fluorescent lamps for 10 min. Following this, the mixture was kept in the dark to terminate the reaction. The absorbance of the mixture was then measured at 560 nm using a spectrophotometer.

The activity of CAT enzymes was determined on the principle of Beers and Sizer29, in which 0.2 ml of enzyme extract was combined with a total of 2.8 ml of a reaction mixture containing hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), monosodium phosphate buffer and distilled water. The activity of the CAT enzyme was determined by spectrophotometric monitoring of the decrease in absorbance at 240 nm, resulting from the enzymatic degradation of H₂O₂.

Observations of alterations in root meristem tissue

In order to assess esfenvalerate-induced changes in root meristem tissue, A. cepa roots collected at the end of the third day were thoroughly washed and transverse sections were taken using a sharp razor blade. Sections were stained with 1% methylene blue and examined and photographed using an Irmeco, IM-450 TI.

Molecular docking analysis

In order to gain insight into the potential interactions of esfenvalerate pesticide with a range of biological macromolecules, a molecular docking analysis was conducted. This involved the examination of the binding potential between the pesticide and a number of important molecules, including tubulins, DNA topoisomerases, glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase, and protochlorophyllide reductase. Additionally, the analysis encompassed the interaction between the pesticide and different type of DNA molecules. The following 3D structures were retrieved from the protein data bank: tubulin (alpha-1B chain and tubulin beta chain) (PDB ID: 6RZB)30, DNA topoisomerase I (PDB ID:1K4T) and II (PDB ID:5GWK)31,32, glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase (PDB ID:2ZSL)33, protochlorophyllide reductase (PDB ID:6R48)34 and B-DNA dodecamer (PDB ID: 1bna)35, B-DNA dodecamer d (PDB ID: 195d)36 and DNA (PDB ID: 1cp8)37. The 3D structures of the esfenvalerate pesticide, identified with the PubChem CID number 10342051, was obtained from the PubChem database. In order to optimize the molecular docking process, the active sites of the proteins were first identified, after which the water molecules and ligands were removed and polar hydrogen atoms were added. The minimization of protein energy was conducted utilizing the Gromos 43B1 method with the Swiss-PdbViewer software38 (version 4.1.0). The minimization of the 3D structure of esfenvalerate was achieved through the application of the uff-force field, employing the Open Babel software (version 2.4.0)39. The receptor molecules were assigned Kollman charges, and esfenvalerate was allocated Gasteiger charges. In order to conduct the molecular docking analysis, a grid box was constructed, incorporating the active sites of the proteins under investigation and the overall structure of the DNA molecules. Subsequently, docking was undertaken using Autodock 4.2.6 molecular modelling software40, which employs a Lamarckian genetic algorithm. In all studied complexes, the lowest binding affinity and lowest root mean square deviation (RMSD) were selected as the ideal docking position, and the upper and lower limits of the RMSD values were taken as zero. Biovia Discovery Studio 2020 Client was used to do the docking analysis and 3D visualizations.

Statistical analysis

Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk anomaly tests were used to evaluate the normality of the data of the four experimental groups. The results revealed that the data showed normal distribution (p > 0.05). IBM SPSS Statistics 23 statistical analysis program was used to analyze the findings of the study. The results are presented as means with standard deviations (mean ± SD). The statistical significance of the data between each group was analyzed using one-way ANOVA and post hoc multiple comparisons (Duncan tests), with a statistical significance of p < 0.05.

Experimental research on plants

Experimental research and field studies on plants and plant parts (A. cepa bulbs), including the collection of plant material, comply with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation.

Results and discussion

Table 1 provides a summary of the impact of esfenvalerate treatment on growth-related physiological parameters in A. cepa. The emergence of roots was observed in all bulbs (100%) within the control group that had been treated with tap water. In contrast, an increase in the dosage of esfenvalerate was followed by a reduction in the rooting percentage. Indeed, in the ESF 3 group treated with 0.98 mg/L esfenvalerate, the percentage of rooting decreased to 49%. Additionally, the application of esfenvalerate resulted in a notable reduction in root elongation and weight gain in all experimental groups, when compared to the control group. The growth retardation induced by esfenvalerate was observed to exhibit a dose-dependent behavior in response to the test chemical. The root elongation and weight gain in the ESF 3 group were found to have decreased by 85.3% and 84.3%, respectively, in comparison to the control group.

Based on the effect of esfenvalerate on root length, the EC50 value was determined as 0.59 mg/L esfenvalerate. The root system is more susceptible to environmental toxicity in the root zone than the stem and leaves. The accumulation of pyrethroids in plant roots is greater than that observed in the other parts41. Therefore, the assessment of root development and growth represents a crucial step in the verification of a plant’s ability to establish and flourish42. In recent years, numerous studies have examined the toxicity of pesticides in A. cepa by investigating the inhibitory effect on root growth43,44,45. The pyrethroid pesticide cypermethrin has also been shown to suppress weight gain in A. cepa bulbs46. Nevertheless, this study represents the first evidence that esfenvalerate induces growth retardation in A. cepa. Seed germination tests have been shown to evaluate soil toxicity directly, whereas root elongation tests take into account the indirect effects of potentially present water components41. The growth of plant roots is determined by the processes of cell proliferation and elongation that occur during the development and differentiation of the root47. The inhibition of root development and growth may be attributed to a limitation in the uptake of water, which is essential for cell division, or it may be due to pesticide-induced oxidative stress. Furthermore, the chemical constituents of pesticides have been demonstrated to impede growth by interfering with the genetic material, mitotic machinery and cell death induction mechanisms47. Zhang et al.48 proposed that fenvalerate may also exert its growth-inhibitory effects by disrupting carbohydrate metabolism.

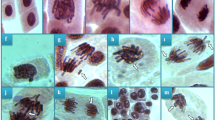

MI is a metric that makes it possible to estimate the frequency of cell division and certain percentages of inhibition of mitotic activity point to the cytotoxicity phenomena in plants49. The impact on MI is dependent on the pesticide type, application dosage and the bioindicator plant species. In all cases, MI shows a decreasing trend as the pesticide dosage rises42. In our study, the administration of esfenvalerate resulted in a reduction in the MI values of A. cepa root tip cells (Table 2). The decline in MI was observed to become more pronounced with an increase in the dosage of the pesticide applied. MI reduction in the ESF 1, ESF 2 and ESF 3 groups was 8.2%, 20.8% and 45.7%, respectively, compared to the control group. The considerable reduction in mitotic activity also suggests the presence of genotoxic potential and a decline in MI to below 50% of the negative control is regarded as sublethal50,51. In the present study, following esfenvalerate treatment, A. cepa root tip cells showed a variety of chromosomal aberrations, including MN (Table 2; Fig. 1). The mean MN frequency values for the ESF 1, ESF 2, and ESF 3 groups were 15.0, 35.0, and 73.0, respectively, when compared to the control group (Table 2). MN (Fig. 1a) is one of the most basic indicators of genetic damage and may be a symptom of clastogenic or aneugenic activity in chromosomes52. These tiny bodies are made of DNA fragments that are either wrongly cleaved or left unrepaired during cell division. As precursors of pesticide-induced genotoxicity in plants, they reflect the ability of pesticides to induce oxidative stress, attack DNA and modify DNA repair mechanisms42,53. The chromosomal aberrations induced by esfenvalerate were ranked according to their frequency of occurrence, as follows: sticky chromosome (Fig. 1b), vagrant chromosome (Fig. 1c), fragment (Fig. 1d), unequal distribution of chromatin (Fig. 1e), bridge (Fig. 1f), vacuolated nucleus (Fig. 1g), reverse polarization (Fig. 1h), and multipolar anaphase (Fig. 1i). While all CA types appeared following the lowest application dose of 0.33 mg/L esfenvalerate, maximum values were reached in the ESF 3 group, where 0.98 mg/L esfenvalerate was applied (Table 2). Stickiness may be caused by partial dissolution of nucleoproteins, chromosome condensation, unusual contraction, DNA depolymerization, excessive nucleoprotein formation, or inter-chromosomal attachment of sub-chromatid strands that are combined by defective protein–protein interactions54. In light of the irreversible nature of this CA, it can be posited that esfenvalerate poses a risk of death for A. cepa cells. A vagrant chromosome is a spindle thread defect that arises when a chromosome relocates to a poleward position in advance of its own set of chromosomes. This phenomenon leads to an unequal distribution of chromosomes in daughter cells55. The occurrence of chromosomal fragments can be attributed to the rupture of double-stranded DNA or the obstruction of DNA replication. Such fragmentation can subsequently lead to the formation of MN56, unbalanced chromosome arrangements and unequal distribution of chromatids51. The formation of bridges is attributed to a number of factors, including chromosome and/or chromatid breakage, unequal chromatid translocation, and the presence of dicentric chromosomes57. The non-disjunction of sticky chromosomes also results in chromosomal bridges54. Vacuolated nucleus represents vacuoles within the nucleus that do not contain genetic material and such nuclear abnormalities have been linked to aneuploidy, which may be another contributing factor in the development of MN58. The existence of multipolar anaphase may be a sign of spindle inactivation and cytokinesis suppression59. This is the first research to show that the pesticide esfenvalerate is genotoxic for A. cepa. Nevertheless, in accordance with our findings, Abdel Rheim et al.2 previously demonstrated the esfenvalerate-induced formation of diverse CAs, including fragment, in rat bone marrow cells. It was also demonstrated that exposure to esfenvalerate in grapes, bush beans, soybeans, pumpkins, and cucumbers resulted in DNA modification due to oxidative stress, membrane lipid peroxidation, and DNA adduct formation60. In addition, cypermethrin, lambdacyhalothrin and deltamethrin, which are among other pyrethroid pesticides, have been proven to increase the frequency of MN and CAs while decreasing MI in A. cepa, similar to our results61. According to the reduction in MI observed following esfenvalerate administration might also be a marker of growth inhibition (Table 1) associated with reduced cell proliferation. Surrallés et al.62 proposed that pyrethroid pesticides have a cyclopropane ring with a methyl group, which leads to cytotoxic effects. Furthermore, Chauhan et al.63 suggested that the greatest effect of these kind of pesticides is on mitotic spindles. Abdel Rheim et al.2, the substances that harm lysosomes and cellular membranes cause lysosomal or other DNAases to be released into the strand break. In cells that survive sublethal damage, these double strand breaks may result in a number of genotoxic effects, including mutation and CAs. The formation of structural CAs can be attributed to a number of factors, including the direct consequence of DNA damage, the replication of a damaged DNA template, the restriction of DNA synthesis, and the inhibition of topoisomerase II2,55. Other potential causes of esfenvalerate-induced cytogenotoxicity in A. cepa may include inhibited DNA synthesis, an interruption in the G2 phase of the cell cycle, CAs formation-related uncompleted cell cycles, and free radical attack on genetic machinery.

Although CAs are indicative of a true genetic effect, the Comet test was employed to elucidate the direct impact of the pesticide on DNA (Table 3). The Comet assay was initially developed in 1984 to detect the migration of DNA fragments from nuclei to an anode under neutral conditions. However, subsequent research showed that it was more sensitive, specific, and reproducible under alkaline conditions64. Pesticides possess the capacity to damage the structure of DNA in A. cepa L.65. In the current version of the Comet assay, the DNA exhibits free mobility and the unwinding of DNA supercoils allows the DNA loops extend from the nuclear core under an electric field to create a comet-like tail. In a cellular level, this makes it possible to detect DNA single or double strand breakages, cross-linked DNA and alkali-labile sites64. Table 3 and Fig. 2 show the esfenvalerate-induced DNA damage detected by the Comet assay. In accordance with the classification proposed by Pereira et al.22, when DNA tail percentage (Table 3) was considered, minimal damage was observed in the control group, while esfenvalerate treatment resulted in moderate’ damage in the ESF1 group and ‘high’ damage in the ESF2 and ESF3 groups. According to the visual scale proposed by Jayawardena et al.23, when taking into account the ratio of tail to core diameter, the control group was undamaged, whereas ‘minor’ damage was observed in the ESF 1 group, and ‘major’ damage in the ESF 2 and the ESF 3 groups as a result of esfenvalerate application. Therefore, the amount of DNA damage increases with tail length. Similarly, the migration distance is inversely proportional to the size of the DNA fragment66. The comet assay results, which were consistent with the results of other genotoxicity parameters (MI, MN and CAs) obtained from our study, showed that esfenvalerate treatment caused direct damage to DNA of A. cepa in a dose-dependent manner. Our results are in agreement with the study showing that esfenvalerate induced a significant increase in the percentage of tail DNA, tail length and tail moment in the Comet assay in rat liver cells2. The comet assay also showed that fenvalerate, another pyrethroid insecticide, caused DNA damage in Columba livia liver cells67. Similarly, cypermethrin was found to significantly increase the percentage of Comet tail DNA in root meristem cells of A. cepa46. Ibrahim et al.68 reported that the insecticide esfenvalerate induced DNA damage and apoptosis via the activation of caspase-3 and DNA fragmentation in neonatal rats. During the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis, cellular disintegration is accelerated when cytochrome C is released because it activates caspase-9 and caspase-3. Esfenvalerate may also induce apoptosis in response to DNA damage by increasing the expression of tumor suppressor proteins such as p5369. DNA strand breakage can lead to loss of cell integrity and toxicity that can result in cell death. A molecular pathway leading to pesticide-induced toxicity occurs due to free radical production. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) attack membranes, initiating lipid peroxidation and forming oxidative lesions on DNA associated with oxidized purines and pyrimidines2. Indeed, Ullah et al.66 posited that a direct relationship exists between ROS, ROS-producing enzymes, and DNA damage. For instance, hydrogen peroxide is a radical that readily penetrates membranes and reaches the nucleus, where it reacts with iron or copper ions to generate a hydroxyl radical, which has the primary damaging function of destroying DNA66,70.

DNA damage induced by esfenvalerate insecticide. Control: Tap water, ESF 1: 0.33 mg/L esfenvalerate, ESF 2: 0.64 mg/L esfenvalerate, ESF 3: 0.98 mg/L esfenvalerate. The visual severity of DNA damage was determined by the ratio between tail and core diameter. No tail (undamaged), tail length less than or equal to the core diameter (minor damage), tail length less than twice the core diameter (medium damage), tail length equal to twice the core diameter (major damage), tail length more than twice the core diameter (maximum damage).

Table 4 summarizes the esfenvalerate-related biochemical alterations. Subsequent to their binding to macromolecules, pesticides are subject to degradation through a series of physiochemical reactions, including autolysis, rearrangement, inactivation, and photolysis. This process results in the regeneration ROS in the cells71. Pesticide-induced ROS production has been demonstrated to cause lipid peroxidation and inevitable triggering or impairment of antioxidant defenses72. Any imbalance between the production of ROS and the capacity of the antioxidant defense system to actively detoxify and neutralize excess ROS is referred to as oxidative stress. This process has the potential to cause extensive damage to cellular components, including membranes and genetic materials73. One of these damages is lipid peroxidation of biological membranes. MDA, a byproduct of polyunsaturated fatty acid oxidation, often referred to as lipid peroxidation, is accumulated when ROS levels are higher than the cell can withstand. It damages the integrity of membranes, making them permeable in a way that interferes with cell functioning74. SOD and CAT are two enzymes that are among the enzymatic components of antioxidant defense and work as a harmonious team53. The SOD enzyme catalyzes the dismutation of the superoxide radical to hydrogen peroxide, while the CAT enzyme catalyzes the conversion of the hydrogen peroxide radical to water and oxygen75. One of the non-enzymatic metabolites accumulated by plants under stress is proline, which serves a number of functions. These include being an osmotic protector, part of the soluble nitrogen pool, an indicator of senescence and a stress resistance signal76. This molecule also functions as a ROS scavenger and alters the solubility of proteins to avoid denaturation under stress76,77. All groups that received esfenvalerate showed remarkable increases in MDA and proline levels as well as SOD and CAT enzyme activities. The ESF 1, ESF 2 and ESF 3 groups had MDA concentrations 1.34, 1.88 and 2.75 times the control group, respectively. In addition, proline levels of these three groups were 1.28, 1.55 and 1.96 times that of the control group, respectively. MDA and proline levels rose with increasing pesticide doses. On the other hand, SOD activities of the ESF 1, ESF 2 and ESF 3 groups were 1.22, 1.44 and 1.35 times that of the control group, respectively. CAT activities of the ESF 1, ESF 2 and ESF 3 groups were 1.21, 2.01 and 1.69 times that of the control group, respectively. Similar to SOD activity, CAT activity increased in the first two esfenvalerate-treated groups (ESF 1 and EFS 2) and decreased slightly in the ESF 3 group exposed to the highest dose of pesticide. Although SOD and CAT activity levels were significantly lower in the ESF 3 group than in the ESF 2 group, enzyme activity levels were significantly higher in all esfenvalerate-treated groups than in the control group. This study presents the first evidence that esfenvalerate elicits oxidative stress in A. cepa. Nevertheless, Hussein et al.78 demonstrated that esfenvalerate induced oxidative stress-related MDA elevation and neurotoxicity in rats. In another study, it was revealed that esfenvalerate exposure up-regulated SOD and CAT gene expressions in Cyprinus carpio8. Interestingly, esfenvalerate induced an elevation in MDA levels and a drop in SOD and CAT activities in albino rats79. This may be due to high-dose esfenvalerate exposure, which can completely impair SOD and CAT mechanisms. Differences in cellular pesticide responses may be due to variations in uptake rates influenced by detoxification, toxicity of metabolic intermediates and membrane composition in different organism. In addition, Ye et al.7 observed alterations in the activities of SOD, CAT and MDA in E. fetida following the application of esfenvalerate. The authors concluded that CAT activity and MDA accumulation were more sensitive biomarkers of oxidative stress induced by esfenvalerate than SOD activity. In the study of Bashir et al.76, deltamethrin, a pyrethroid pesticide, induced a remarkable increment in both MDA and proline levels in Glycine max. The study conducted by Ayhan et al.46 revealed that the application of the synthetic pyrethroid insecticide cypermethrin resulted in an increase in proline and MDA accumulation, as well as an enhancement in SOD and CAT activities. According to El-Demerdash80, the oxidative damage caused by pyrethroids is due to their lipophilic structure, which facilitates the easy penetration of these pesticides into the cell membrane, and these pesticides can easily produce a large number of ROS, including superoxide radical. It has been demonstrated that pyrethroids can induce mitochondrial dysfunction and enhance apoptotic pathways by altering the antioxidant activities of enzymes such as SOD and CAT81. Additionally, one of the consequences of severe oxidative damage induced by pyrethroid pesticide stress is the loss of structural integrity in enzymes80. The partial reduction of SOD and CAT in the ESF 3 group in comparison to the other two groups treated with esfenvalerate (Table 4), along with the other severe damage observed in this group (Tables 1, 2, 3), suggests that the applied dose may pose a risk of detrimental harm to A. cepa. Indeed, the elevated levels of damage in the ESF 3 group may be attributed to the heightened accumulation of H₂O₂ within this group, which has been demonstrated to promote lipid peroxidation and modulate DNA. In addition to lipid peroxidation, esfenvalerate can also disrupt normal ion flux across membranes by binding to sodium (Na+) channels in the cell membrane, and thus increased Na+ accumulation in the cell can result in cell swelling. Loss of both membrane integrity and cellular ion balance disrupts Ca2+ homeostasis, affecting intracellular signaling pathways and leading to the development of novel stress responses82. All in all, oxidative stress and DNA damage are closely related83 and esfenvalerate is an “oxidative stress trigger” for A. cepa. As the results of our study on genotoxicity may confirm, ROS, including superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals, may play a role in various forms of DNA damage, including single- and double-strand breaks, alkali-stable sites, and purine and pyrimidine oxidation83. It has been reported that the protective mechanism of proline against pyrethroid pesticide exposure is not only associated with the support of ROS detoxification, scavenging of free radicals and membrane stabilization, but also with the biosynthesis of glutathione, which plays an important role in pesticide detoxification84. The alteration of photosynthetic pigments in plants is a commonly employed indicator for the evaluation of stress conditions. The concentrations of chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b in the esfenvalerate-treated groups exhibited a notable and dose-dependent decline (Table 4). The concentration of chlorophyll a in the ESF 1, ESF 2 and ESF 3 groups was observed to decrease by 14.71%, 38.82% and 58.18%, respectively, in comparison to the control group. In a similar fashion, the quantity of chlorophyll b present in these groups was observed to diminish by 26.41%, 47.78% and 70.35%, respectively, when compared to the control group. Similar to our findings, Shakir et al.85 demonstrated that high doses of alpha-cypermethrin, imidacloprid, emamectin benzoate and lambda-cyhalothrin pesticides resulted in a reduction of both chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b levels in Lycopersicon esculentum. In addition, prolonged exposure of dimethoate insecticide to pigeon pea plants decreased chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b levels86. It is possible that pesticides may modify the biosynthesis of chlorophyll by affecting the formation of plastids or the conversion of plastids to chloroplasts87. Chopade et al.88 proposed that the excessive or unintentional utilization of pesticides results in mutational alterations to chlorophylls or their decomposition via catabolic processes. Moreover, the role of pesticides in chlorophyll degradation was linked to their potential to cause oxidative stress by Siddiqui et al.89. The synchronous occurrence of chlorophyll degradation and ROS accumulation during the process of senescence lends further support to this hypothesis48. The reduction in chlorophyll pigmentation observed in plants subjected to esfenvalerate stress (Table 4) may also be associated with the diversion of glutamate, the precursor molecule for both proline and chlorophyll, towards proline synthesis90.

Molecular docking studies play a pivotal role in elucidating the interactions between small molecules and macromolecules, offering valuable insights into their potential impacts on cellular processes90. In the present study, we conducted molecular docking analyses to assess the binding affinities and interactions of esfenvalerate, a pyrethroid insecticide, with a spectrum of vital macromolecules. The selected macromolecules encompassed tubulins, DNA topoisomerases, glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase, and protochlorophyllide reductase, which are crucial components of the cellular machinery involved in microtubule dynamics, DNA topology, amino acid metabolism, and chlorophyll biosynthesis, respectively91,92,93. The interactions between esfenvalerate and these macromolecules are of particular interest due to their potential implications for cellular health. Disruption of microtubule dynamics, as mediated by tubulins, can affect various cellular processes, including cell division and intracellular transport94. Perturbations in DNA topology, regulated by DNA topoisomerases, may lead to karyotypic alterations, such as chromosomal aberrations95. Moreover, modulation of glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase can influence amino acid metabolism96 while interactions with protochlorophyllide reductase may impact chlorophyll biosynthesis and photosynthetic efficiency97. In this study, the results of the molecular docking analysis are presented in Table 5 and Fig. 3, showcasing the binding affinities and interaction patterns of esfenvalerate with the selected macromolecules. These findings provide a foundation for understanding the potential impacts of esfenvalerate at the molecular level and its implications for cellular processes, chromosomal stability, and photosynthetic efficiency.

The molecular interactions of esfenvalerate with selected macromolecules. Tubulin alpha 1B chain (a), tubulin beta chain (b), DNA topoisomerase I (c), DNA topoisomerase II (d), glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase (e), protochlorophyllide reductase (f). The figure was drawn using the Biovia Discovery Studio 2020 Client software.

The molecular docking analysis revealed that esfenvalerate exhibited a high binding affinity with the Tubulin alpha-1B chain, with a free energy of binding calculated as -8.17 kcal/mol. The inhibition constant (Ki) was determined to be 1.03 μM. This interaction was primarily characterized by multiple hydrogen bond interactions, particularly involving THR179 and ALA12. Hydrophobic interactions played a significant role in stabilizing the binding, with contributions from residues such as GLN11, ILE171, TYR224, ALA12 and ALA99. In the case of the Tubulin beta chain, esfenvalerate exhibited a binding affinity with a free energy of − 7.47 kcal/mol and an inhibition constant (Ki) of 3.35 μM. Interestingly, the interaction with the Tubulin beta chain lacked hydrogen bond interactions but was predominantly stabilized by hydrophobic interactions. Residues such as ALA18, PHE81, VAL76, PRO80, and LYS19 were involved in hydrophobic contacts, which contributed to the binding. These findings indicate that esfenvalerate may have an impact on microtubule stability, potentially affecting various cellular processes.

The molecular docking analysis showed that esfenvalerate exhibited a binding affinity with DNA topoisomerase I with a free energy of -6.40 kcal/mol and an inhibition constant (Ki) of 20.36 μM. The binding interactions primarily involved hydrogen bonds with residues such as ASN491 and ARG488. Additionally, hydrophobic interactions were observed with ALA489, ALA586, LYS587, ARG488, LYS532 and LYS493. Esfenvalerate demonstrated a binding affinity with DNA topoisomerase II with a free energy of − 6.78 kcal/mol and an inhibition constant (Ki) of 10.72 μM. The interaction was characterized by hydrogen bond interactions with THR767 and hydrophobic interactions involving MET766, ARG713 and PRO724. This suggests that esfenvalerate may influence the function of DNA topoisomerase I and II, potentially affecting DNA topology.

In the case of glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase, esfenvalerate exhibited a binding affinity with a free energy of − 7.53 kcal/mol and an inhibition constant (Ki) of 3.02 μM. The interaction involved hydrogen bond interactions with SER120 and LYS271, as well as hydrophobic interactions with VAL245, TYR148, PRO278, and VAL279. These findings suggest that esfenvalerate may interfere with the function of glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase, potentially impacting processes related to amino acid metabolism.

Esfenvalerate displayed a strong binding affinity with protochlorophyllide reductase, with a free energy of binding calculated as − 9.85 kcal/mol and an inhibition constant (Ki) of 60.24 nM. This interaction was characterized by hydrogen bond interactions with TYR219, PRO220, and TYR189. Additionally, hydrophobic interactions with VAL14, LEU139, LEU228, LYS193, LYS152, ILE153, ILE155, and LYS190 contributed to the binding. These findings suggest that esfenvalerate could potentially disrupt the role of protochlorophyllide reductase, with potential repercussions on the intricate process of chlorophyll biosynthesis and its interconnected cellular pathways.

In this study, molecular docking analyses were conducted to explore the binding interactions between esfenvalerate, a pyrethroid insecticide, and three distinct DNA molecules: B-DNA dodecamer (1BNA), B-DNA dodecamer D (195D), and DNA (1CP8). The results of the docking analysis provide valuable insights into the potential effects of esfenvalerate on DNA structure and function. The findings, as presented in Table 6 and Fig. 4, indicate that esfenvalerate interacts with these DNA molecules, albeit with varying affinities. Esfenvalerate interacted with B-DNA dodecamer (1BNA) with a binding energy of − 7.33 kcal/mol and an inhibition constant of 4.24 uM. These interactions involved nucleotides G4 and A5 in chain A, and C21, G22, C23 in chain B. In the context of B-DNA dodecamer D (195D), esfenvalerate exhibited notable affinity by interacting with the A8 nucleotide in chain A, and nucleotides A19, A20, and C21 in chain B, resulting in a binding energy of − 8.51 kcal/mol and an inhibition constant of 578.28 nM. Furthermore, the interaction between esfenvalerate and DNA (1CP8) yielded a binding energy of -8.26 kcal/mol and an inhibition constant of 881.83 μM, encompassing interactions with nucleotides G4, C6, and A7 in chain A, and G3 and C6 in chain B.

The results stemming from our molecular docking investigations between esfenvalerate and diverse DNA molecules reveal the compound’s capability for intercalation, facilitated by interactions with both identical and distinct strands within DNA molecules All these molecular docking results indicate that esfenvalerate may interact with DNA that may have effects on its structural stability and conformational changes, which in turn may affect the role of DNA in storing genetic information and various cellular functions. Furthermore, our findings suggest that esfenvalerate can potentially modulate DNA structure by preferentially binding to regions rich in G-A, C-G-C, A-A, G-C-A, and G-C nucleotides.

The microscopic examination of cross-sectional samples revealed the damage caused to the root meristem of A. cepa by esfenvalerate insecticide. Esfenvalerate-induced damage types and their severity are given in Table 7 and Fig. 5. All meristematic structures examined in the control group treated with tap water displayed a normal appearance (Fig. 5a,c,g). On the other hand, the application of different doses of esfenvalerate caused an increase in meristematic damage in a dose-dependent manner. The application of 0.33 mg/L esfenvalerate to the ESF 1 group resulted in the observation of epidermis cell damage (Fig. 5b), cortex cell damage (Fig. 5d), thickened cortex cell wall (Fig. 5e) and flattened cell nucleus (Fig. 5h) type damage, which were classified as ‘minor’ levels of damage. Similarly, the application of 0.64 mg/L esfenvalerate to the ESF 2 group resulted in the observation of material accumulation in cortex cells (Fig. 5f), which were also classified as ‘minor’ levels of damage. The 0.98 mg/L esfenvalerate applied ESF 3 group demonstrated the highest level of damage for each damage type. This is the first study to demonstrate that esfenvalerate causes damage to meristematic tissue in plant roots. Conversely, Chauhan and Gupta98 reported that deltamethrin, another pyrethroid insecticide, resulted in irreversible damage to the meristem ultrastructure of A. cepa root cells. In a similar manner to the observations made in our study, insecticides cypermethrin caused damage to epidermis cells, flattened cell nuclei, thickened cortex cell walls and caused cortex cell damage in A. cepa as a result of oxidative stress16,46. Our findings regarding the activities of SOD and CAT enzymes and MDA levels are consistent with the interpretation of Kutluer et al.12, who stated that peroxidation of lipids as a result of oxidative stress can lead to deformation and shape changes in cell and nuclear membranes in plants. Conversely, Singh et al.99 posited that plants employ a defensive mechanism to prevent the penetration of harmful chemicals into their cells. This involves the accumulation of chemical compounds, including lignin, cellulose, suberin, and cutin, within cells and cell walls, which serves to reinforce and thicken the wall, thereby creating a barrier against potential cellular damage. In addition. The observed flattened cell nuclei are indicative of not only physical deformation but also of genetic damage to the genetic material, as evidenced by the genotoxicity results of this study.

Meristematic tissue damage types induced by esfenvalerate insecticide. Normal appearance of epidermis cells (a), epidermis cell damage (b), normal appearance of cortex cells (c), cortex cell damage-red area (d), thickened cortex cell wall (e), material accumulation in cortex cells (f), normal appearance of cell nucleus-oval (g), flattened cell nucleus (h). Bar = 10 µM.

Conclusion

The widespread and excessive use of pesticides in agriculture worldwide has become one of the most important concerns for both wildlife and human health. While the use of synthetic pyrethroids has been promoted as a safer alternative, there is an increasing body of evidence indicating that these chemicals can have adverse effects on non-target organisms. Despite the acknowledged hazardous nature of esfenvalerate, a prevailing synthetic pyrethroid insecticide, there is a clear deficiency in the existing body of research concerning its toxic effects on plants. This study revealed the potential toxicity of esfenvalerate insecticide in A. cepa, a recognized model plant, from a number of perspectives. The results indicated that A. cepa was subjected to severe oxidative stress induced by esfenvalerate. This oxidative stress to cellular structures and processes, including DNA, is probably the primary contributing factor to phytotoxicity. Furthermore, molecular docking analysis demonstrated that esfenvalerate can directly interact with DNA, as well as with molecules involved in cell division and genetic integrity, resulting in damage to these molecules. These findings provide valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms driving the toxicity of esfenvalerate, suggesting that the oxidative damage observed in A. cepa likely parallels the broader physiological effects seen in other organisms, including mammals. Nevertheless, the precise molecular pathways through which esfenvalerate exerts its toxic effects remain to be elucidated. In future studies, we aim to fill this gap by investigating physiological pathways and various molecular interactions. The results of the study are expected to provide a framework for further research on the adverse effects of esfenvalerate on humans and experimental animals, offer insights into the legal regulations that govern the use of esfenvalerate, and raise awareness of the toxicity of esfenvalerate on wildlife and non-target species including agricultural plants.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kaur, R. et al. Pesticides: An alarming detrimental to health and environment. Sci. Total Environ. 915, 170113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.170113 (2024).

Abdel Rheim, F., Ragab, A. A., Hammam, F. & Hamdy, H. E. D. Evaluation of DNA damage in vivo by comet assay and chromosomal aberrations for pyrethroid insecticide and the antimutagenic role of curcumin. Egypt. J. Hosp. Med. 59, 172–181. https://doi.org/10.12816/0012174 (2015).

Giri, S., Sharma, G. D., Giri, A. & Prasad, S. B. Fenvalerate-induced chromosome aberrations and sister chromatid exchanges in the bone marrow cells of mice in vivo. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 520, 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1383-5718(02)00197-3 (2002).

Birolli, W. G., Alvarenga, N., Seleghim, M. H. & Porto, A. L. Biodegradation of the pyrethroid pesticide esfenvalerate by marine-derived fungi. Mar. Biotechnol. 18, 511–520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10126-016-9710-z (2016).

Ahamad, A. & Kumar, J. Pyrethroid pesticides: An overview on classification, toxicological assessment and monitoring. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 10, 100284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hazadv.2023.100284 (2023).

Ranatunga, M., Kellar, C. & Pettigrove, V. Toxicological impacts of synthetic pyrethroids on non-target aquatic organisms: A review. Environ. Adv. 12, 100388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envadv.2023.100388 (2023).

Ye, X., Xiong, K. & Liu, J. Comparative toxicity and bioaccumulation of fenvalerate and esfenvalerate to earthworm Eisenia fetida. J. Hazard. Mater. 310, 82–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.02.010 (2016).

Navruz, F. Z., Acar, Ü., Yılmaz, S. & Kesbiç, O. S. Dose-dependent stress response of esfenvalerate insecticide on common carp (Cyprinus carpio): Evaluating blood parameters and gene expression. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 272, 109711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpc.2023.109711 (2023).

Rodrigues, A. C. et al. Sub-lethal toxicity of environmentally relevant concentrations of esfenvalerate to Chironomus riparius. Environ. Pollut. 207, 273–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2015.09.035 (2015).

Holdway, D. A. et al. Toxicity of pulse-exposed fenvalerate and esfenvalerate to larval Australian crimson-spotted rainbow fish (Melanotaenia fluviatilis). Aquat. Toxicol. 28, 169–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-445X(94)90032-9 (1994).

Macar, O., Kalefetoğlu Macar, T., Çavuşoğlu, K., Yalçın, E. & Yapar, K. Lycopene: An antioxidant product reducing dithane toxicity in Allium cepa L. Sci. Rep. 13, 2290. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-29481-4 (2023).

Kutluer, F., Özkan, B., Yalçin, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Direct and indirect toxicity mechanisms of the natural insecticide azadirachtin based on in-silico interactions with tubulin, topoisomerase and DNA. Chemosphere 364, 143006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2024.143006 (2024).

Rampanelli, J. C., Zuchello, F. & Mores, R. Analysis of cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of sweeteners using Allium cepa bioassays. Acta Sci. Biol. Sci. 46, e68303. https://doi.org/10.4025/actascibiolsci.v46i1.68303 (2024).

Kalefetoğlu Macar, T. & Macar, O. A study on the effect of Hypericum perforatum L. extract on vanadium toxicity in Allium cepa L.. Sci. Rep. 14, 28486. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79535-4 (2024).

Çakir, F., Kutluer, F., Yalçin, E., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Acar, A. Deep neural network and molecular docking supported toxicity profile of prometryn. Chemosphere 340, 139962. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.139962 (2023).

Himtaş, D., Yalçin, E., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Acar, A. In-vivo and in-silico studies to identify toxicity mechanisms of permethrin with the toxicity-reducing role of ginger. Environ. Sci. and Pollut. Res. 31, 9272–9287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-31729-5 (2024).

Hamilton, D. Esfenvalerate. In Pesticide residues in food (ed. Hamilton, D.) 579–653 (Joint FAO/WHO Meeting on Pesticide Residues, 2002).

Topatan, Z. Ş et al. Alleviatory efficacy of Achillea millefolium L. in etoxazole-mediated toxicity in Allium cepa L.. Sci. Rep. 14, 31674. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81586-6 (2024).

Staykova, T. A., Ivanova, E. N. & Velcheva, D. G. Cytogenetic effect of heavy-metal and cyanide in contaminated waters from the region of southwest Bulgaria. J. Cell Mol. Biol. 4, 41–46 (2005).

Fenech, M. et al. HUMN project: Detailed description of the scoring criteria for the cytokinesis-block micronucleus assay using isolated human lymphocyte cultures. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 534, 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1383-5718(02)00249-8 (2003).

Chakraborty, R., Mukherjee, A. K. & Mukherjee, A. Evaluation of genotoxicity of coal fly ash in Allium cepa root cells by combining comet assay with the Allium test. Environ. Monit. Assess. 153, 351–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-008-0361-z (2009).

Pereira, C. S. A. et al. Evaluation of DNA damage induced by environmental exposure to mercury in Liza aurata using the comet assay. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 58, 112–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00244-009-9330-y (2010).

Jayawardena, U. A., Wickramasinghe, D. D. & Udagama, P. V. Cytogenotoxicity evaluation of a heavy metal mixture, detected in a polluted urban wetland: Micronucleus and comet induction in the Indian green frog (Euphlyctis hexadactylus) erythrocytes and the Allium cepa bioassay. Chemosphere 277, 130278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.130278 (2021).

Witham, F. H., Blaydes, D. R. & Devlin, R. M. Experiments in plant physiology (ed Witham, F.H.) (Van Nostrand Reinhold Co, 1971).

Bates, L. S., Waldren, R. P. A. & Teare, I. D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil. 39, 205–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00018060 (1973).

Ünyayar, S., Celik, A., Çekiç, F. Ö. & Gözel, A. Cadmium-induced genotoxicity, cytotoxicity and lipid peroxidation in Allium sativum and Vicia faba. Mutagenesis 21, 77–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/mutage/gel001 (2006).

Zou, J., Yue, J., Jiang, W. & Liu, D. Effects of cadmium stress on root tip cells and some physiological indexes in Allium cepa var. agrogarum L.. Acta Biol. Cracov. Ser. Bot. 54, 129–141. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10182-012-0015-x (2012).

Beauchamp, C. & Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutase: Improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 44, 276–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(71)90370-8 (1971).

Beers, R. F. & Sizer, I. W. A spectrophotometric method for measuring the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide by catalase. J. Biol. Chem. 195, 133–140 (1952).

Lacey, S. E., He, S., Scheres, S. H. & Carter, A. P. Cryo-EM of dynein microtubule-binding domains shows how an axonemal dynein distorts the microtubule. Elife 8, e47145. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.47145 (2019).

Staker, B. L. et al. The mechanism of topoisomerase I poisoning by a camptothecin analog. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99, 15387–15392. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.242259599 (2002).

Wang, Y. R. et al. Producing irreversible topoisomerase II-mediated DNA breaks by site-specific Pt (II)-methionine coordination chemistry. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 10861–10871. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx742 (2017).

Mizutani, H. & Kunishima, N. Crystal structure of glutamate-1-semialdehyde 2,1-aminomutase from Aeropyrum pernix. https://doi.org/10.2210/pdb2ZSL/pdb (2011).

Zhang, S. et al. Structural basis for enzymatic photocatalysis in chlorophyll biosynthesis. Nature 574, 722–725. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1685-2 (2019).

Drew, H. R. et al. Structure of a B-DNA dodecamer: Conformation and dynamics. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 78, 2179–2183. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.78.4.2179 (1981).

Balendiran, K., Rao, S. T., Sekharudu, C. Y., Zon, G. & Sundaralingam, M. X-ray structures of the B-DNA dodecamer d (CGCGTTAACGCG) with an inverted central tetranucleotide and its netropsin complex. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 51, 190–198. https://doi.org/10.1107/S0907444994010759 (1995).

Katahira, R. et al. Solution structure of the novel antitumor drug UCH9 complexed with d (TTGGCCAA) 2 as determined by NMR. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 744–755. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/26.3.744 (1998).

Guex, N. & Peitsch, M. C. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-Pdb Viewer: An environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 18, 2714–2723. https://doi.org/10.1002/elps.1150181505 (2005).

O’Boyle, N. M. et al. Open Babel: An open chemical toolbox. J. Cheminf. 3, 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/1758-2946-3-33 (2011).

Morris, G. M. et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 2785–2791. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.21256 (2009).

Bragança, I., Lemos, P. C., Barros, P., Delerue-Matos, C. & Domingues, V. F. Phytotoxicity of pyrethroid pesticides and its metabolite towards Cucumis sativus. Sci. Total Environ. 619, 685–691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.11.164 (2018).

Salazar Mercado, S. A. & Correa, R. D. C. Examining the interaction between pesticides and bioindicator plants: An in-depth analysis of their cytotoxicity. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31, 51114–51125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-024-34521-1 (2024).

Sheikh, N., Patowary, H. & Laskar, R. A. Screening of cytotoxic and genotoxic potency of two pesticides (malathion and cypermethrin) on Allium cepa L.. Mol. Cell. Toxicol. 16, 291–299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13273-020-00077-7 (2020).

Amaç, E. & Liman, R. Cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of clopyralid herbicide on Allium cepa roots. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 48450–48458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-13994-4 (2021).

Bouzekri, A., Nassar, M. & Slimani, S. The insecticide spirotetramat may induce cytotoxic and genotoxic effects on meristematic cells of Allium cepa L. and Vicia faba L.. Cytologia 88, 225–231. https://doi.org/10.1508/cytologia.88.225 (2023).

Ayhan, B. S. et al. Comprehensive analysis of royal jelly protection against cypermethrin-induced toxicity in the model organism Allium cepa L. employing spectral shift and molecular docking approaches. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 203, 105997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pestbp.2024.105997 (2024).

Miranda, L. A., de Souza, V. V., Campos, R. A., de Campos, J. M. S. & da Silva Souza, T. Phytotoxicity and cytogenotoxicity of pesticide mixtures: Analysis of the effects of environmentally relevant concentrations on the aquatic environment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 112117–112131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-30100-y (2023).

Zhang, D. et al. Chemical induction of leaf senescence and powdery mildew resistance involves ethylene-mediated chlorophyll degradation and ROS metabolism in cucumber. Hortic. Res. 9, uhac101. https://doi.org/10.1093/hr/uhac101 (2022).

Bonciu, E. Clastogenic potential of some chemicals used in agriculture monitored through the Allium assay. Sci. Papers Ser. Manag. Econom. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 23, 63–68 (2023).

Jain, P., Singh, P. & Sharma, H. P. Anti-proliferative activity of some medicinal plants. Int. J. Pharmacol. Pharm. Sci. 3, 46–52 (2016).

Graña, E. Mitotic index. In Advances in plant ecophysiology techniques (eds Sánchez-Moreiras, A. & Reigosa, M.) 231–240 (Springer, 2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93233-0_13.

Drzymała, J. & Kalka, J. Assessment of genotoxicity, mutagenicity, and cytotoxicity of diclofenac and sulfamethoxazole at environmental concentrations on Vicia faba. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 21, 3633–3648. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-023-05238-4 (2024).

Kalefetoğlu Macar, T. Investigation of cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of abamectin pesticide in Allium cepa L.. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 2391–2399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-10708-0 (2021).

Jayalal, N. A. & Yatawara, M. Toxicity assessment of powdered laundry detergents: An in vivo approach with a plant-based bioassay. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31, 59166–59178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-024-35158-w (2024).

Sabeen, M. et al. Allium cepa assay based comparative study of selected vegetables and the chromosomal aberrations due to heavy metal accumulation. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 27, 1368–1374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2019.12.011 (2020).

Pharmawati, M. & Wrasiati, L. P. Chromosomal and nuclear alteration induced by nickel nitrate in the root tips of Allium cepa var. aggregatum. Pollution 9, 702–711. https://doi.org/10.22059/poll.2022.349167.1634 (2023).

Boumaza, A., Ergüç, A. & Orhan, H. The cytotoxic, genotoxic and mitotoxic effects of Atractylis gummifera extract in vitro. Afr. Health Sci. 24, 295–306. https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v24i1.35 (2024).

Anbumani, S. & Mohankumar, M. N. Gamma radiation induced micronuclei and erythrocyte cellular abnormalities in the fish Catla catla. Aquat. Toxicol. 122, 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquatox.2012.06.001 (2012).

Barman, M. & Ray, S. Cytogenotoxic effects of 3-epicaryoptin in Allium cepa L. root apical meristem cells. Protoplasma 260, 1163–1177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00709-023-01838-6 (2023).

Boerth, D. W. et al. DNA adducts as biomarkers for oxidative and genotoxic stress from pesticides in crop plants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 56, 6751–6760. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf072816q (2008).

Yekeen, T. A. & Adeboye, M. K. Cytogenotoxic effects of cypermethrin, deltamethrin, lambdacyhalothrin and endosulfan pesticides on Allium cepa root cells. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 12, 6000–6006. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJB2013.12802 (2013).

Surrallés, J. et al. Induction of micronuclei by five pyrethroid insecticides in whole-blood and isolated human lymphocyte cultures. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. 341, 169–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1218(95)90007-1 (1995).

Chauhan, L. K. S., Saxena, P. N. & Gupta, S. K. Cytogenetic effects of cypermethrin and fenvalerate on the root meristem cells of Allium cepa. Environ. Exp. Bot. 42, 181–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0098-8472(99)00033-7 (1999).

Costea, M. A. et al. the comet assay as a sustainable method for evaluating the genotoxicity caused by the soluble fraction derived from sewage sludge on diverse cell types, including lymphocytes, Coelomocytes and Allium cepa L. cells. Sustainability 16, 457. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010457 (2024).

Hasnian, A. et al. Assessment of the genotoxic effect of pesticide (profenophos and cypermethrin) on Allium cepa L. through comet assay. J. Bioresour. Manag. 1, 92–101 (2024).

Ullah, S., Zuberi, A., Ullah, I. & Azzam, M. M. Ameliorative role of vitamin C against cypermethrin induced oxidative stress and dna damage in Labeo rohita (Hamilton, 1822) using single cell gel electrophoresis. Toxics 12, 664. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics12090664 (2024).

Agarwal, P. & Singh, V. K. Comparative comet assay analysis of liver cells of Columba livia after short and long duration oral exposure of fenvalerate and ziram. Ind. J. Biol. Stud. Res. 3, 129–133 (2014).

Ibrahim, K., El-Desouky, M., Abou-Yousef, H., Gabrowny, K. & El-Sayed, A. Imidacloprid and/or esfenvalerate induce apoptosis and disrupt thyroid hormones in neonatal rats. Global J. Biotechnol. Biochem. 10, 106–112. https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.gjbb.2015.10.03.1121 (2015).

Schuler, M., Bossy-Wetzel, E., Goldstein, J. C., Fitzgerald, P. & Green, D. R. p53 induces apoptosis by caspase activation through mitochondrial cytochrome c release. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 7337–7342. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.275.10.7337 (2000).

Paravani, E. V., Simoniello, M. F., Poletta, G. L. & Casco, V. H. Cypermethrin induction of DNA damage and oxidative stress in zebrafish gill cells. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 173, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.02.004 (2019).

Fatma, F., Verma, S., Kamal, A. & Srivastava, A. Phytotoxicity of pesticides mancozeb and chlorpyrifos: Correlation with the antioxidative defence system in Allium cepa. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants. 24, 115–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12298-017-0490-3 (2018).

Jacobsen-Pereira, C. H. et al. Markers of genotoxicity and oxidative stress in farmers exposed to pesticides. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 148, 177–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.10.004 (2018).

Sule, R. O., Condon, L. & Gomes, A. V. A common feature of pesticides: Oxidative stress-the role of oxidative stress in pesticide-induced toxicity. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 5563759. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5563759 (2022).

Goel, C., Kumar, N., Tripathi, A., Tiwari, S. & Shrivastava, A. Assessment of malondialdehyde and organochlorine pesticides in aplastic anemia severity groups: insights into oxidative stress and exposure. Cureus 16, e59698. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.59698 (2024).

Jan, S. et al. The pesticide thiamethoxam induced toxicity in Brassica juncea and its detoxification by Pseudomonas putida through biochemical and molecular modifications. Chemosphere 342, 140111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.140111 (2023).

Bashir, F., Siddiqi, T. O. & Iqbal, M. The antioxidative response system in Glycine max (L.) Merr. exposed to Deltamethrin, a synthetic pyrethroid insecticide. Environ. Pollut. 147, 94–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2006.08.013 (2007).

Tang, Y. et al. Proline inhibits postharvest physiological deterioration of cassava by improving antioxidant capacity. Phytochem 224, 114143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2024.114143 (2024).

Hussein, J. S. et al. Amelioration of neurotoxicity induced by esfenvalerate: impact of Cyperus rotundus L. tuber extract. Comp. Clin. Path. 30, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00580-020-03182-0 (2021).

Abdel Rheim, F., Ragab, A. A., Hammam, F. & Hamdy, H. E. D. Protective effects of curcumin for oxidative stress and histological alterations induced by pyrethroid insecticide in albino rats. Egypt. J. Hosp. Med. 58, 63–73. https://doi.org/10.12816/0009362 (2015).

El-Demerdash, F. M. Lipid peroxidation, oxidative stress and acetylcholinesterase in rat brain exposed to organophosphate and pyrethroid insecticides. Food Chem. Toxicol. 49, 1346–1352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2011.03.018 (2011).

Khan, A. M., Raina, R., Dubey, N. & Verma, P. K. Effect of deltamethrin and fluoride co-exposure on the brain antioxidant status and cholinesterase activity in Wistar rats. Drug. Chem. Toxicol. 41, 123–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/01480545.2017.1321009 (2018).

Ray, D. E. & Forshaw, P. J. Pyrethroid insecticides: Poisoning syndromes, synergies, and therapy. J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 38(95–101), 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1081/clt-100100922 (2000).

Odetti, L. M., González, E. C. L., Siroski, P. A., Simoniello, M. F. & Poletta, G. L. How the exposure to environmentally relevant pesticide formulations affects the expression of stress response genes and its relation to oxidative damage and genotoxicity in Caiman latirostris. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 97, 104014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.etap.2022.104014 (2023).

Kumar, A., Yadav, P. K. & Singh, A. Mitigating cypermethrin stress in Amaranthus hybridus L.: Efficacy of foliar-applied salicylic acid on growth, enzyme activity, and metabolite profiles. Plant Stress. 14, 100673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stress.2024.100673 (2024).

Shakir, S. K. et al. Effect of some commonly used pesticides on seed germination, biomass production and photosynthetic pigments in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum). Ecotoxicology 25, 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10646-015-1591-9 (2016).

Pandey, J. K., Dubey, G. & Gopal, R. Study the effect of insecticide dimethoate on photosynthetic pigments and photosynthetic activity of pigeon pea: Laser-induced chlorophyll fluorescence spectroscopy. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 151, 297–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2014.08.014 (2015).

Salem, R. Side effects of certain pesticides on chlorophyll and carotenoids contents in leaves of maize and tomato plants. Middle East J. Agric. Res. 5, 566–571 (2016).

Chopade, A. R., Naikwade, N. S., Nalawade, A. Y., Shinde, V. B. & Burade, K. B. Effects of pesticides on chlorophyll content in leaves of medicinal plants. Pollut. Res. 26, 491 (2007).

Siddiqui, Z. H., Abbas, Z. K., Ansari, A. A., Khan, M. N. & Ansari, W. A. Pesticides and their effects on plants: A case study of deltamethrin. In Agrochemicals in soil and environment: Impacts and remediation (eds Naeem, M. et al.) 183–193 (Springer Nature, 2022).

Kitchen, D. B., Decornez, H., Furr, J. R. & Bajorath, J. Docking and scoring in virtual screening for drug discovery: Methods and applications. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 3, 935–949. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd1549 (2004).

Wang, J. C. Cellular roles of DNA topoisomerases: A molecular perspective. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 430–440. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm831 (2002).

Buey, R. M., Díaz, J. F. & Andreu, J. M. The nucleotide switch of tubulin and microtubule assembly: A polymerization-driven structural change. Biochemistry 45, 5933–5938. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi060334m (2006).

Vedalankar, P. & Tripathy, B. C. Evolution of light-independent protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase. Protoplasma 256, 293–312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00709-018-1317-y (2019).

Parker, A. L., Kavallaris, M. & McCarroll, J. A. Microtubules and their role in cellular stress in cancer. Front. Oncol. 4, 153. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2014.00153 (2014).

Zagnoli-Vieira, G. & Caldecott, K. W. Untangling trapped topoisomerases with tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterases. DNAREP 94, 102900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dnarep.2020.102900 (2020).

Grimm, B. Glutamate 1-semialdehyde aminotransferase, a unique enzyme in chlorophyll biosynthesis. In Biochemistry of Vitamin B6 and PQQ (eds Marino, G. et al.) 99–103 (Birkhäuser Basel, 1994).

Fujita, Y. & Bauer, C. E. Reconstitution of light-independent protochlorophyllide reductase from purified BchL and BchN-BchB subunits: In vitro confirmation of nitrogenase-like features of a bacteriochlorophyll biosynthesis enzyme. J. Bil. Chem. 275, 23583–23588. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m002904200 (2000).

Chauhan, L. K. S. & Gupta, S. K. Combined cytogenetic and ultrastructural effects of substituted urea herbicides and synthetic pyrethroid insecticide on the root meristem cells of Allium cepa. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 82, 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pestbp.2004.11.007 (2005).

Singh, D., Pal, M., Singh, R., Singh, C. K. & Chaturvedi, A. K. Physiological and biochemical characteristics of Vigna species for Al stress tolerance. Acta Physiol. Plant. 37, 87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11738-015-1834-7 (2015).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.S, T.K.M., O.M., E.Y. and K.Ç. designed the experiments; O.S, T.K.M., O.M., E.Y., K.Ç, A.A. and A.A. performed the analyses; K.Ç. carried out the statistical analysis; O.S., T.K.M. and O.M. wrote the manuscript with the help of E.Y., K.Ç., A.A. and A.A.; O.M. edited the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sarsar, O., Macar, O., Kalefetoğlu Macar, T. et al. Multifaceted investigation of esfenvalerate-induced toxicity on Allium cepa L.. Sci Rep 15, 16977 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01638-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01638-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A new efficient immunoprotocol to detect chromosomal/nuclear proteins along with repetitive DNA in squash preparations of formalin-fixed, long-stored root tips

Plant Methods (2025)

-

Quantitative phenolic profiling and protective effects of grape seed extract on mancozeb-induced cellular and genetic toxicity

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Ramalina farinacea mitigates cytogenotoxicity and physiological, biochemical, and anatomical alterations induced by nickel in Allium cepa

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Eco-friendly remediation of Triflumuron-induced stress with Capsella bursa-pastoris extract

Scientific Reports (2025)