Abstract

Oomycota, a diverse group of fungus-like protists, play key ecological roles in aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, yet their habitat-specific diversity and distribution remain poorly understood. This study investigates the diversity of two major Oomycota classes, Saprolegniomycetes and Peronosporomycetes, in two freshwater lakes and their adjacent forests in northeastern Germany. Using a combination of targeted metabarcoding and traditional isolation techniques, we analyzed samples from six habitats, including soil (forest), rotten leaves (forest and shoreline), sediments (shoreline), and surface waters (littoral and pelagic zones). Metabarcoding revealed 401 Oomycota OTUs, with Pythium, Globisporangium, and Saprolegnia as dominant genera. Culture-based methods identified 110 strains, predominantly from surface water and sediment, with Pythium sensu lato and Saprolegnia as the most frequent taxa. Alpha and beta diversity analyses highlighted distinct community structures influenced by lake and habitat type, with significant co-occurrence of Saprolegniomycetes and Peronosporomycetes across habitats. This study provides the first comprehensive metabarcoding-based exploration of Oomycota biodiversity in interconnected freshwater and terrestrial ecotones, uncovering previously unrecognized patterns of habitat-specific diversity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oomycota, a diverse group of fungus-like protists, play essential roles in both aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, ranging from saprotrophic decomposers to plant and animal pathogens. Despite their global ecological and economic importance, our understanding of their distribution and diversity across habitats remains limited, largely due to a historical focus on specific taxa in particular environments1,2,3. While it is well-established that the classes Saprolegniomycetes and Peronosporomycetes inhabit both freshwater and terrestrial environments, research has predominantly focused on the first in freshwater systems and the latter in soils. Saprolegniomycetes have been extensively studied as pathogens of amphibians and fish (e.g., Saprolegnia parasitica), and crayfish (e.g., Aphanomyces astaci)4,5,6, but there are, albeit fewer, several studies examining their occurrence in soil environments7,8. A well-documented case of Saprolegniomycetes in terrestrial environments is Aphanomyces euteiches, which thrives in moist soils and primarily causes root rot disease in leguminous plants9. Conversely, while members of Peronosporomycetes are infamous for their plant pathogenic roles in soil environments - such as Pythium ultimum10 (now Globisporangium ultimum) and Phytophthora infestans11, both with broad host ranges - some studies have explored their presence in freshwater ecosystems12,13,14, though such instances remain comparatively less thoroughly investigated. This uneven focus across freshwater and terrestrial ecosystems has resulted in a limited understanding of the true diversity, co-occurrence, and ecological roles of Saprolegniomycetes and Peronosporomycetes across these habitats.

In addition to the uneven research focus across freshwater and terrestrial ecosystems, several other factors contribute to our limited understanding of Saprolegniomycetes and Peronosporomycetes diversity and ecological roles. First, research has long relied on culture-based techniques15, which tend to favor fast-growing and abundant taxa, and miss rare or unculturable ones. Second, these methods are highly selective, typically isolating only certain genera while overlooking others16,17, which complicate comparative studies and limits insights into the distribution of Saprolegniomycetes and Peronosporomycetes across different environments. However, recently developed metabarcoding approaches have begun to overcome these challenges. Unlike culture-based methods, metabarcoding enables the detection of both fast-growing and rare/unculturable taxa, providing a more comprehensive view of microbial diversity. The application of metabarcoding to study Saprolegniomycetes and Peronosporomycetes is relatively recent, with most studies thus far focusing on soil environments18,19 and only a limited number addressing freshwater ecosystems20. This emerging technique holds promise for broadening our understanding on environmental ranges and functions of these groups across terrestrial and aquatic habitats.

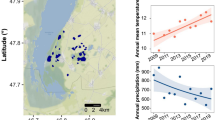

Therefore, in this study, we aimed to investigate the diversity of Saprolegniomycetes and Peronosporomycetes in two distinct freshwater lakes (NE Germany), namely Grosse Fuchskuhle and Grosser Stechlinsee, and their adjacent forests. Forested areas (primarily beech and pine trees) encircle both lakes, and their watersheds remain largely unaffected by human activities. Lake Grosse Fuchskuhle is a naturally acidic bog lake while Grosser Stechlinsee is a dimictic calcareous lake. We used (I) a targeted metabarcoding approach and (II) classic isolation techniques. To our knowledge, this is the first study exploring Oomycota biodiversity in freshwater lakes using a targeted metabarcoding approach, complemented by samples from surrounding forest areas. Our findings reveal the co-occurrence of both Saprolegniomycetes and Peronosporomycetes across freshwater and forest environments, providing new insights into the diversity and distribution of Oomycota and their ecological roles in interconnected ecosystems.

Results

Overall diversity from the metabarcoding approach

The OTU database contained 401 Oomycota OTUs after assembly and quality filtering, representing ~ 1.2 million Illumina reads. Samples from the rotten leaves (shoreline) and surface water (littoral) from both lakes showed the highest number of OTUs while the lowest OTU numbers were detected from sediment (shoreline) (Grosse Fuchskuhle) and surface water (pelagic) (Grosser Stechlinsee) (Fig. 1). Pythium sensu lato (including Globisporangium, and Pythium sensu stricto) was the most abundant and diverse detected taxon across all habitats, followed by Saprolegnia, Aphanomyces, and Achlya (Fig. 1, Supplementary Material 1). Analyzing the six habitats of both lakes individually, Saprolegniomycetes and Peronosporomycetes always occurred together, although in different abundances (Figs. 1 and 2a and d, Supplementary Figure S1). For instance, in Grosse Fuchskuhle, rotten leaves (forest and shoreline) and surface water (pelagic) were more dominated by Peronosporomycetes (Fig. 2a). Similarly, rotten leaves (forest and shoreline), sediments (shoreline), and surface water (littoral) habitats in Grosser Stechlinsee contained more Peronosporomycetes than Saprolegniomycetes (Fig. 2d). At both lakes sites, the soil (forest) was dominated by Saprolegniomycetes.

Similar composition patterns of genera emerged when dividing habitats into freshwater and terrestrial. Pythium sensu lato and Saprolegnia were the most commonly detected OTUs from freshwater habitats of both lakes (Fig. 2b and e). Additionally, we unexpectedly observed ~ 23% of detected OTUs associated with Lagena (Peronosporomycetes) in freshwater habitats of Grosser Stechlinsee. Terrestrial habitats of both lakes, similar to freshwater ones, were dominated by Pythium sensu lato as the most common OTUs (Fig. 2c and f). High occurrence of OTUs associated with Saprolegnia (~ 30%) and Leptolegnia (~ 14%) was observed in the terrestrial habitats from Grosse Fuchskuhle. Moreover, high occurrence of Apodachlya, the only genus which does not belong to Saprolegniales or Peronosporales, was only observed in the terrestrial habitats of Grosser Stechlinsee.

The relative abundance of detected Oomycota OTUs across the aquatic-terrestrial ecotones from Lakes Grosse Fuchskuhle (left) and Grosser Stechlinsee (right) using a metabarcoding approach. (a and d) Relative contribution of Saprolegniomycetes (Saprolegniales and Leptomitales) and Peronosporomycetes (Peronosporales and Paralagenidiales) to the diversity of six habitats in each lake. (b and e) Sankey diagrams showing the relative contribution of sequences to the overall taxonomic diversity of freshwater habitats in lakes Grosse Fuchskuhle and Grosser Stechlinsee. (c and f) Sankey diagrams showing the relative sequence contribution to the overall taxonomic diversity of terrestrial habitats from Grosse Fuchskuhle and Grosser Stechlinsee. Taxonomic assignment is based on the best hit by BLAST. Numbers represent sequence read percentages. The digital drawings in (a) and (d) were drawn by Adobe Photoshop 21 (https://www.adobe.com/products/photoshop.html).

Alpha and beta diversity

Alpha diversity differed greatly between the sampling sites (Fig. 3a). Specifically, ChaoRichness differed between both lakes (ANOVA: F1, 60 = 11.9410, p = 0.001) and habitats (F5, 60 = 20.0158, p < 0.001). Moreover, Oomycota richness did not behave equally for both lakes and the habitats (lake: habitat interaction: F5, 60 = 5.7096, p < 0.001), suggesting that both lake properties and specific habitat types contribute to variations in Oomycota richness. The remaining alpha diversity metrics (exponential Shannon index/ChaoShannon, inverse Simpson index/ChaoSimpson, Supplementary Figure S2) and Pielou’s evenness index/ChaoEvenness (Fig. 3a) differed between habitats (ChaoShannon: F5, 60 = 13.9144, p < 0.001, ChaoSimpson: F5, 60 = 12.4671, p < 0.001, ChaoEvenness: F5, 60 = 11.8723, p < 0.001), but not between both lakes.

Alpha and beta diversity analysis based on six habitats from Grosse Fuchskuhle and Grosser Stechlinsee and DESeq2 analysis. (a) Boxplots displaying alpha diversity metrics (OTU richness and Pielou’s evenness index). Letters above the boxplots are derived from pairwise comparisons using Tukey’s honest significance test (0.05 significance level). (b) NMDS plot based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarities. Replicates (small symbols) from the same sampling sites were grouped, their centroids (large symbols) were displayed, and sampling sites were differentiated by habitat (color) and lake (symbol and hull). (c) Metacoder heat tree displaying differentially abundant genera between freshwater and terrestrial habitats from DESeq2 analysis. Genera in blue are more abundant in freshwater habitats/less abundant in terrestrial habitats, and genera in brown are more abundant in terrestrial habitats/less abundant in freshwater habitats. Thickness of the branches refers to the observed number of OTUs of the respective taxon.

Beta diversity of Oomycota was strongly influenced by the lakes (PERMANOVA: F1, 60 = 17.307, p < 0.001) and habitats (F5, 60 = 13.184, p < 0.001). The influence of lake and habitat type on the Oomycota community composition was not consistent but differed between lakes, or habitat types, respectively (lake: habitat interaction, F5, 60 = 11.026, p < 0.001), i.e., samples from the same habitat type were not necessarily more similar to one another when originating from different lakes, and the two lakes did not show the same patterns for all habitats (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Figure S3). Overall, the sampling sites exhibited distinct community compositions, with some notable patterns emerging. Terrestrial forest samples (soil and rotten leaves) were highly similar to each other, as were the freshwater samples, though not as pronounced. However, aquatic samples from Grosse Fuchskuhle grouped more closely with the terrestrial forest samples than those from Grosser Stechlinsee. Notably, rotten leaves (shoreline) from Grosse Fuchskuhle were very similar to rotten leaves (forest) from both lakes, and sediment (shoreline) samples from Grosse Fuchskuhle showed great similarity to soil (forest) samples from both lakes (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Figure S3). The tested factors collectively explained a substantial portion of the variability in community composition, with habitat and the lake: habitat interaction being the strongest drivers (R² = 0.08725 for lake, 0.33234 for habitat, 0.27792 for lake: habitat interaction).

Shared and differentially abundant OTUs

The majority of obtained OTUs was shared between freshwater and terrestrial habitats from both lakes (228 out of 401 OTUs, Supplementary Figure S4) with very few exclusively detected in one specific lake or habitat type (aquatic or terrestrial). As an example, only two and one OTUs were exclusively detected in freshwater habitats of Grosser Stechlinsee and Grosse Fuchskuhle, respectively. The same was true for terrestrial habitats with zero OTUs exclusively detected in terrestrial habitats of any of the lakes. Notably, the freshwater habitats of both lakes shared a relatively high number of OTUs (47 of 401; 12%) that were completely absent from the terrestrial samples, while only one single OTU was found exclusively in the terrestrial habitats.

Taxa that have been historically reported to be mostly terrestrial (e.g., Globisporangium, Phytophthora, Pythium) were indeed more common in the terrestrial habitats (Fig. 3c), however, especially Pythium and Globisporangium were sometimes the dominant genera in freshwater habitats (e.g., in surface water (pelagic zone) from Grosse Fuchskuhle, or in rotten leaves (shoreline) of Grosser Stechlinsee (Supplementary Figure S1)). Aphanomyces and Saprolegnia were neither more abundant in freshwater nor in terrestrial habitats. Notably, both Saprolegniomycetes and Peronosporomycetes contained genera that were more abundant in terrestrial or freshwater habitats. For instance, in Saprolegniomycetes, Apodachlya, Leptolegnia, and Pythiopsis were more common in the terrestrial samples, whereas Achlya and Blastulidium were more abundant in aquatic environments. Similarly, in Peronosporomycetes, some genera such as Halophytophtora and the previously mentioned Globisporangium, Phytophthora, and Pythium were more prevalent in terrestrial samples, while genera like Peronospora and Phytiogeton were more abundant in aquatic samples (Fig. 3c).

Overall diversity from isolation techniques

In total, we isolated 110 strains from lakes Grosse Fuchskuhle (60) and Grosser Stechlinsee (50) using Saprolegniales- and Peronosporales-specific isolation methods. The success rate of Oomycota isolation was 59% as nearly 41% of isolated strains belonged to either Ascomycota and Mucoromycota (fungi), mostly isolated from either soil (forest) or rotten leaves (forest) habitats adjacent to both lakes (Fig. 4). The highest number of isolated Oomycota strains were associated with surface water (pelagic and littoral zones) and sediment (shoreline) in both lakes, respectively. Moreover, Pythium sensu lato and Saprolegnia were the most frequent and diverse Oomycota strains as they were isolated from all habitats and phylogenetically associated with different species based on ITS sequences (Fig. 5). In Grosse Fuchskuhle, strains were grouped in seven clades associated with Saprolegnia aenigmatica, Leptolegnia caudata, Achlya klebsiana, Elongisporangium undulatum, Phytopythium sp., Pythium rishiriense, and P. pachycaule (Fig. 5). Additionally, strains from Grosser Stechlinsee were closely related to four, one, and four species in Saprolegnia, Achlya, and Pythium sensu lato clades, respectively (Fig. 5).

In most cases, strains that were grouped in one clade (= identical based on their ITS sequences) had been isolated from two or three types of freshwater habitats. For instance, in Grosse Fuchskuhle, Elongisporangium sp. P1 F09, P2 E05, and P1 H10 were isolated from both surface water (littoral and pelagic) and rotten leaves (shoreline). The same is true for Grosser Stechlinsee, where Pythium sp. P2 D07, P2 G10, and P2 B02 had been isolated from rotten leaves and sediment (shoreline), and surface water (littoral zone) (Fig. 5).

Phylograms of the best ML trees revealed by RAxML from an analysis of the internal transcribed spacers 1 and 2, and 5.8 S gene of rDNA sequences for Saprolegniales and Peronosporales strains isolated from Grosse Fuchskuhle and Grosser Stechlinsee using selective culture-based baiting techniques for each order.

Discussion

While previous research using culture-based baiting methods has revealed the presence of Saprolegniomycetes and Peronosporomycetes in both freshwater and terrestrial ecosystems, it often lacked a comparative framework to examine their co-occurrence and relative distributions in both habitats. Our study addressed this gap using a metabarcoding approach, enabling a systematic analysis of the Oomycota community across freshwater and terrestrial ecosystems. By complementing metabarcoding with classical isolation techniques, we revealed patterns of habitat overlap and specificity that were previously obscured by methodological biases. We observed a striking pattern of low sequence similarity to reference database matches among Saprolegniomycetes OTUs in terrestrial ecosystems and Peronosporomycetes OTUs in freshwater habitats, suggesting the presence of numerous potentially undescribed taxa and highlighting their underexplored diversity.

Genera such as Phytophthora and Pythium (Peronosporomycetes) are commonly recognized as plant pathogens, whereas Achlya, Aphanomyces, and Saprolegnia (Saprolegniomycetes) are known to cause diseases in amphibians, crayfish, and fish21,22. Nevertheless, the above-mentioned separation is gradually being faded, particularly in the light of high throughput techniques such as metabarcoding. Supported by several metabarcoding-based studies, it has been shown that Saprolegniomycetes and Peronosporomycetes normally co-occur in soil18 and, to a much lesser extent, in water environments20. Fiore-Donno and Bonkowski (2021)23 deployed the metabarcoding approach used in this study to understand the distribution of Oomycota in temperate grasslands and forests. Up to 21% of their detected OTUs could be associated with Saprolegniomycetes. Our results showed a similar co-occurrence pattern in forest soil as well as freshwater habitats. Additionally, although we successfully isolated both Saprolegniomycetes and Peronosporomycetes strains using culture-based techniques, the limitations of these methods must be acknowledged. Firstly, culture-based techniques showed low efficiency, particularly in terrestrial habitats (soil and rotten leaves) where most of the isolated strains were either Ascomycota or Mucoromycota (fungi). Secondly, these methods distorted the overall picture of diversity as several Oomycota genera such as Apodachlya, Phytophthora, Pythiopsis, Lagena, and Lagenidium only detected by the metabarcoding approach. Finally, although hemp seeds and grass are common types of bait for the isolation of Saprolegniomycetes and Peronosporomycetes strains, they could introduce further biases as they might not be effective in the isolation of some genera.

A deeper understanding of Oomycota diversity across habitats raises important questions about the ecological roles of common as well as rare taxa. Our findings revealed that although Pythium sensu lato significantly contributes to the diversity of the community even in freshwater habitats, very little is known about their potential function(s). It could be either associated with fish and/or other aquatic plant diseases24,25,26,27, exploit freshwater environments as a transmission route for infection of terrestrial plants and further geographic distribution28,29, or simply act as litter decomposers.

Additionally, the significant presence of Lagena OTUs in the Grosser Stechlinsee freshwater habitats challenged the current notion of this genus as a soil inhabitant23,30 and/or causal agent of brown root rot in wheat and related grasses31,32,33. Our results can be explained by the fact that Lagena is also reported to be widely present in the roots of Phragmites australis34 which is, interestingly, the main shoreline vegetation of Grosser Stechlinsee. More recently, Lagena has been detected from a stream in Iceland with parasitoid nature against diatoms which is phylogenetically separated from the plant-associated clade35. Whether our Lagena OTUs are associated with the plant- or diatom-infecting clades remains to be answered in the future.

Moreover, the detection of Saprolegnia, a commonly known fish and amphibian pathogen36,37 from the soil samples of Grosse Fuchskuhle supports classic taxonomy-based studies where it has been reported from soil environments38,39. However, their possible ecological contribution to soil environments remains unanswered. One could argue that Saprolegnia might have undergone specific evolutionary adaptations and ecological versatility, allowing it to explore both land and water and acquire certain lifestyles. This argument is supported by the evidence from Saprolegnia’s close evolutionary relative, Aphanomyces, which comprises certain taxa as plant pathogens and others as crayfish and fish pathogens4,5,6,7,8,9.

It is not surprising that the observed diversity of the Oomycota community in our study is strongly influenced by the lake type, as Grosse Fuchskuhle and Grosser Stechlinsee differed markedly in their trophic status40,41. In particular, Grosse Fuchskuhle is a humic matter-rich lake which is influential in determining its biodiversity and ecological dynamics. For example, Perkins et al. (2019)42 and Allgaier and Grossart (2006)43 reported significant differences in fungal and bacterial community and diversity between the two lakes, mainly driven from their distinctive dissolved organic matter (DOM) composition. Although our results showed robust differences between the Oomycota community of both lakes, the underlying mechanisms driving this connection remain unclear and warrant further investigation. There are culture-based studies showing the possible impact of DOM, including humic substances, on sporulation44, vegetative growth45, and ability to degrade/transform refractory organic matter by some members of Oomycota46,47. Further studies incorporating experimental approaches and high-resolution molecular techniques are necessary to unravel the specific interactions between Oomycota and DOM components, as well as their broader implications for ecosystem processes in humic matter-rich versus clear-water lakes.

Finally, we need to acknowledge the limitations of our study to guide future research directions. Firstly, since the metabarcoding approach does not take viability into account48, we cannot be sure whether all detected OTUs are active and contributing to the ecology of their habitats. It is plausible that some detected OTUs are dead/dormant propagules of Oomycota washed into the freshwater habitats or transported passively to the forest. Culture-based techniques can compensate for this limitation to some extent but can be implemented only on a small scale and work on abundant, fast-growing Oomycota. Therefore, the metabarcoding approach should be complemented by methods such as metatranscriptomics49 in which functions of Oomycota can be investigated within their residing habitat.

Additionally, a comparison between the sequences of the isolates vs. the metabarcoding OTUs showed that some of the isolated strains do not have a proper match from our metabarcoding OTU database (Supplementary Material 2). This observation is partially explained by the fact that we used different sets of primers for both techniques, resulting in the amplification of different fragments that do not always match. Furthermore, it could be associated with the biases of culture-dependent techniques, as stated above, or due to amplification biases during the metabarcoding resulting in some OTUs which have been excluded during filtering steps due to low abundance in the dataset.

Besides, although we have included six different habitats along the aquatic-terrestrial ecotones of two distinct lakes in our study, the complexity of lake ecosystems may not be fully captured by our results. For instance, we exclusively collected floating rotten leaves from Fagus sylvatica, the dominant vegetation in the surrounding terrestrial environments of both lakes. Therefore, we might have encountered a different species composition of Oomycota if we collected leaves from other plant species. Moreover, one could argue that the diversity of Oomycota might experience successional shifts50,51, with certain OTUs colonizing less-decomposed leaves and others dominating as decomposition progresses. Accordingly, the Oomycota community is likely driven by seasonal changes, a factor not addressed in our study. Additionally, our results indicate that the level of eutrophication likely plays a role in influencing the community in freshwater, further highlighting the importance of environmental conditions. To address these limitations, we recommend further spatiotemporal studies52,53 to understand how the Oomycota community interacts with biotic and/or abiotic factors54 in their habitats over time.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that the Oomycota community is more diverse and widespread across interconnected freshwater and terrestrial habitats than previously assumed. Metabarcoding revealed a broad taxonomic range, including traditionally “aquatic” groups in soil and “terrestrial” groups in freshwater environments, while culture-based approaches highlighted certain biases and missed taxa. Environmental conditions, such as dissolved organic matter, lake type, and habitat characteristics, influenced the composition and distribution of Oomycota, resulting in a distinct community for each habitat, while still displaying a substantial ecological overlap between terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. These findings challenge long-standing notions about Oomycota habitat preferences and underscore the importance of employing integrative techniques and broader sampling efforts to fully understand their ecological roles and environmental drivers.

Methods

Study sites and sampling design

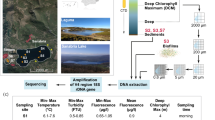

We compared the Oomycota community of two contrasting lakes with distinctive nutrient availability differences, the oligo-/mesotrophic lake ‘Grosser Stechlinsee’ (53° 9’ 7.301” N, 13° 1’ 23.894” E) and the dystrophic lake ‘Grosse Fuchskuhle’ (53° 6’ 19.674” N, 12° 59’ 5.626” E) in northeast Germany plus their surrounding terrestrial habitats. Samples were collected in January 2023 from six different habitats, including surface water from pelagic zones and littoral, homogenized sediment (5 cm depth) from the shoreline, floating rotten leaves (Fagus sylvatica L) from the shoreline, rotten leaves from the forest floor and mineral soil of the forest floor (5 cm depth). Samples from lawn mineral soil (5 cm depth, 53° 08’ 29.1” N 13° 01’ 49.04” E) were used as positive controls, but not further analyzed. Six replicates were collected per sampling site. Surface water (littoral and pelagic), sediment (shoreline), and rotten leaves (shoreline) represented freshwater habitats while terrestrial habitats were represented by rotten leaves and mineral soil from forest.

DNA extraction, amplification, and sequencing for the metabarcoding approach

Water samples were passed through 5.0 μm cyclopore track etched membranes (Cytiva, US) with reusable filter units (Thermo Fisher Scientific, US) connected to a portable 2 l single-stage vacuum pump (Value, Poland). The membranes were placed in 2 ml sterilized safe-lock tubes. Additionally, three grams of sediment or soil, and single rotten leaves (cut in 25 pieces, 1 cm x 1 cm in size) were put in separate 2 ml sterilized safe-lock tubes. All tubes were kept at − 80 °C until DNA extraction.

DNA extraction was conducted as follows55: Firstly, one full lab scoop of zirconium beads with three sizes (0.1, 0.7, and 1 mm) were equally added to 2 ml sterilized safe-lock tubes containing folded 5.0 μm cyclopore track etched membranes, sediment, rotten leaves, or soil. Then, 650 µl of 2X CTAB-Buffer (1 g 2% CTAB, 4.09 g 1.4 M NaCl, 0.29225 g 20 mM EDTA, and 0.788 g 100 mM Tris HCl filled with Diethylpyrocarbonat-water to 50 ml pH 8.0) was added, followed by 65 µl 10% Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 65 µl 10% N-Lauroylsarcosine, and 10.4 µl Proteinase K (20 mg/ml). Tubes were kept in the thermomixer for one hour at 60 °C. 650 µl Phenol-Chloroform-Isoamyl Alcohol (25:24:1) was added to each tube and placed in the FastPrep (MP Biomedicals) under the recommended setting. Tubes were then centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 x g at 4 °C, followed by transferring 650 µl of the upper phase into new tubes. 650 µl Chloroform-Isoamylalkohol was added to each new tube and centrifuged once again (14000 x g at 4 °C). The upper phase was transferred to new tubes containing 2 Vol. (1300 µl) PEG/NaCl (4.7 g 1.6 M NaCl and 15 g 30% PEG 6000 filled with 50 ml DEPC-water). Tubes were incubated at 4 °C for at least 12 h. Tubes were centrifuged for 60 min at 17,000 x g at 4 °C, and the supernatant was removed. The pellet was washed with 800 µl 70% ice-cold ethanol and centrifuged (17000 x g for 10 min at 4 °C). 70% ethanol was pipetted off from tubes completely. Finally, 50 µl 10 mM Tris was added to the tubes and incubated for one hour at 35 °C. The final products were stored at −20 °C.

DNA was diluted 1:30 in nuclease-free water before PCRs. The ITS1 region of Oomycota was amplified in a semi-nested metabarcoding approach using Oomycota-specific primers23. Two consecutive PCRs were performed: The first PCR was conducted with the primer pair S1777F (5′-GGTGAACCTGCGGAAGGA-3′) and 58SOomR (5′-TCTTCATCGDTGTGCGAGC-3′), and the second PCR with barcoded primers S1786StraF (5′-GCGGAAGGATCATTACCAC-3′) and barcoded 58SOomR23. Each sample was amplified with a unique combination of barcoded primers (double indexing) in the second PCR (Supplementary Material 3). One µl of purified DNA served as template for the first PCR, resulting in amplicons of which 1 µl was used for the second semi-nested PCR. Both PCR rounds were conducted with reagents in the following final concentrations: DreamTaq polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Dreieich, Germany) 0.01 units, Thermo Scientific DreamTaq Green Buffer, dNTPs 0.2 mM, and primers 1 mM. Both PCRs were conducted using the following PCR conditions: Initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, 24 cycles (denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 58 °C for 30 s, elongation at 72 °C for 30 s), terminal extension at 72 °C for 5 min, and cooling at 15 °C. All PCRs were conducted in duplicates. Positive controls (DNA from grassland soil) as well as negative controls (water) were added to each PCR batch. After checking for successful amplification by gel electrophoresis, 12.5 µl of the two PCR products of each sample were pooled, purified, and normalized using the SequalPrep Normalization Plate Kit (Invitrogen GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany) to obtain a concentration of 1–2 ng/µl per sample. All purified amplicons were then pooled, concentrated, and sequenced on a MiSeq platform (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) at the Cologne Center for Genomics (Germany).

Sequence processing

Reads were processed in mothur v.1.45.356. Reads were assembled and demultiplexed according to their barcode sequences, not allowing any mismatches in the barcode and primer sequences, allowing a maximum of two mismatches, and no ambiguities in the sequences. Assembled sequences with an overlap < 170 bp were discarded. Merged contigs were demultiplexed and primer and tag sequences were trimmed. Remaining reads were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) by abundance-based greedy clustering (agc) with a similarity threshold of 97% using vsearch57. OTUs representing less than 0.005% of all reads (i.e., < 106 reads) were removed as they likely represent amplification or sequencing errors58. Sequences were blasted (Nucleotide BLAST, blastn) against a custom Oomycota database based on NCBI GenBank with an e-value of 1e−10. Only the best hit was retained, and non-Oomycota sequences were discarded. Sequences with an alignment to sequence length ratio of less than 0.7 were removed since aligning to a reference alignment and chimera detection often led to false eliminations of sequences due to the high variability in length of the ITS1 region. The quality-filtered OTU database was used for all subsequent statistical analyses.

The taxonomic assignment was manually curated. In particular, OTUs assigned to Pythium needed manual correction since the genus Pythium has undergone taxonomic changes during the last years59, and many sequences in the NCBI database are still falsely assigned to Pythium. Representative OTU sequences were manually re-blasted (blastn) against the full NCBI GenBank database for accurate genus-level identification, and classifications were updated to reflect current taxonomy. A rough assignment of ecological traits to the OTUs was performed on genus-level23.

Statistical analyses

All data analyses were conducted in R version 4.1.160. The respective R code is provided in the supplement (Supplementary Material 4). Sankey diagrams displaying the relative abundance at different taxonomic resolutions were calculated for each sampling site with the riverplot package61 using a custom function from Freudenthal et al. (2024)62. Additionally, pie charts displaying the relative abundance of orders were calculated using R base functions and ggplot263.

The data was not rarefied, but instead extrapolated by using the iNEXT package64 for the calculation of alpha diversity indices. From the OTU tables, the extrapolated alpha diversity indices OTU richness, exponential Shannon index, and inverse Simpson index were calculated using iNEXT::ChaoRichness, iNEXT::ChaoShannon, and iNEXT::ChaoSimpson, respectively. Pielou’s evenness index was then calculated from extrapolated Shannon index and OTU richness. Differences in alpha diversity metrics were analyzed using Type I SS analysis of variance (ANOVA). A post-hoc Tukey’s honest significance test (0.05 significance level) was performed for pair-wise comparisons of the groups.

Differences in community structure between the sampling sites (beta diversity) were investigated by multivariate approaches. Total abundances of OTUs were converted to relative abundances and log(+ 1) transformed. Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarities was performed using the vegan::metaMDS function65. Initial two-dimensional NMDS analysis yielded a stress value greater than 0.2, which indicates a poor fit and insufficient representation of the data in a reduced-dimensional space. To address this, we performed three-dimensional NMDS, which provided a better representation of the data. NMDS was visualized to depict patterns in community similarity/dissimilarity, focusing on the influence of the sampled habitats and lakes. Statistical testing was performed with permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA, vegan::adonis2, 9999 permutations, Bray-Curtis dissimilarities). The model was constructed in the same way as the ANOVA models.

Venn diagrams displaying the shared OTUs between lakes and aquatic/terrestrial habitats were constructed using the VennDiagram package66. Differential abundance analysis was conducted in DESeq267 and displayed as a heat tree using metacoder68.

Isolation of Saprolegniales and Peronosporales strains

Soil (3 g), sediment (3 g), and one rotten leaf (10 pieces from the same leaf used for metabarcoding, 1 cm x 1 cm in size) were transferred to separate 10 cm Petri dishes containing 15 ml of autoclaved lake water with 25 boiled hemp seeds (for Saprolegniales) or CMA medium (40 gl-1 ground cornmeal, 15 gl-1 agar) (for Peronosporales); both autoclaved lake water and CMA medium were amended with ampicillin and fluconazole (0.1 g/L each) to avoid fungal and/or bacterial contamination69. Petri dishes were sealed, incubated at room temperature, and daily checked for colonization. Upon colonization, mycelium was transferred to CMA agar with antibiotics. This step was repeated two more times until any visible fungal and/or bacterial contaminations were removed.

For single-spore isolation, five small blocks of CMA agar (1 cm x 1 cm) containing mycelia were transferred into a Petri dish containing autoclaved lake water inoculated with 25 boiled hemp seeds (for Saprolegniales) and boiled grass (for Peronosporales). Petri dishes were checked every 12 h for zoospore sporulation. Upon zoospore sporulation, 5 µl liquid was collected and transferred to a Petri dish containing CMA agar with antibiotics. The germination tube produced by one single zoospore was cut with a sterile needle and transferred to another Petri dish containing CMA agar with antibiotics. This Petri dish with the pure strain was kept at 4 °C for future use46,70.

For the isolation of Oomycota from water (littoral and pelagic zones), two cheesecloth bags containing 25 boiled hemp seeds (for Saprolegniales) or boiled grass (for Peronosporales) were attached to experimental platforms installed in the littoral and pelagic zones of the surface of water in both lakes. After five days, boiled hemp seeds were transferred to Petri dishes containing 10 ml of autoclaved lake water. The subsequent isolation procedure followed the process described above.

DNA extraction, amplification, and sequencing for living Oomycota strains

DNA of Oomycota cultures was extracted using chelex method71 with some modifications: Briefly, strains’ mycelial mats were transferred to 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes containing 150 µL of autoclaved 5% Chelex® 100 (BIO-RAD), incubated in a thermoblock at 100 °C for 10 minutes, vortexed for 10 seconds, and then returned to the thermoblock for another 10 minutes at 100 °C. Samples were subsequently centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4 °C. The resulting supernatants were stored at –20 °C until further use. The nuclear ITS-rDNA region was amplified in a Flexible PCR Thermocycler (Analytikjena, Germany) using ITS1/ITS4 primers72. The program for amplification was: 94 °C for 2 min of initial denaturation followed by 32 cycles of 94 °C for 15 s, 53 °C for 15 s, 72 °C for 30 s, and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The resulting sequences were edited in BioEdit73 and submitted to GenBank (National Center for Biotechnology Information; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Phylogenetic analysis for living Oomycota strains

The generated sequences of our isolates were used as a query for BLASTn analyses in the NCBI database. Sequences linked to voucher cultures with high identity to the query were chosen for phylogenetic analysis, as well as additional sequences from possible relatives were added based on referencing literature in the database74,75. Alignments were produced with MAFFT v. 7.490 (http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/73) and checked and refined using MEGA774. After the exclusion of ambiguously aligned regions and long gaps, the final matrix was chosen. Maximum Likelihood (ML) analyses were performed with RAxML78 as implemented in raxmlGUI v. 1.376 using the ML + rapid bootstrap setting and the GTRGAMMA substitution model with 1000 bootstrap replicates. A table summarizing all used strains, their corresponding sequences, and GenBank accession numbers can be found in Supplementary Table S1.

Data availability

The raw Illumina sequences are available in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/home) under the accession number PRJEB77433 (secondary study accession: ERP161867). Sequences of isolated strains generated in this study (Supplementary Table S1) are available in NCBI GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) under the accession numbers PP995820-PP995845 and PP995782-PP995819. The datasets and R code are available in Supplementary Material 4. The results from Functional guilds are provided in Supplementary Table S2.

Change history

13 January 2026

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article, Supplementary Information files were omitted. The Supplementary Information files now accompany the original Article. The main Article content is unchanged and remains correct from the time of publication.

References

Burki, F. The eukaryotic tree of life from a global phylogenomic perspective. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol. 6, a016147 (2014).

Beakes, G. W., Glockling, S. L. & Sekimoto, S. The evolutionary phylogeny of the Oomycota fungi. Protoplasma 249, 3–19 (2012).

Beakes, G. W. & Thines, M. Hyphochytriomycota and Oomycota in Handbook of the Protists (eds. Archibald, J. M., Simpson, A. G. B. & Slamovits, C. H.) 435–505 (Springer, 2017).

Svoboda, J., Mrugała, A., Kozubíková-Balcarová, E. & Petrusek, A. Hosts and transmission of the crayfish plague pathogen Aphanomyces astaci: a review. J. Fish. Dis. 40, 127–140 (2017).

Lone, S. A. & Manohar, S. Saprolegnia parasitica, a lethal Oomycota pathogen: demands to be controlled. J. Infect. Mol. Biol. 6, 36–44 (2018).

Czeczuga, B., Kozłowska, M. & Godlewska, A. Zoosporic aquatic fungi growing on dead specimens of 29 freshwater crustacean species. Limnologica 32, 180–193 (2002).

Steciow, M. M. The occurrence of Achlya recurva (Saprolegniales, Oomycota) in hydrocarbon-polluted soil from Argentina. Rev. Iberoam Micol. 14, 135–137 (1997).

Inaba, S. & Tokumasu, S. Saprolegnia semihypogyna sp. nov., a saprolegniaceous Oomycota isolated from soil in Japan. Mycoscience 43, 73–76 (2002).

Gaulin, E., Jacquet, C., Bottin, A. & Dumas, B. Root rot disease of legumes caused by Aphanomyces euteiches. Mol. Plant. Pathol. 8, 539–548 (2007).

Lévesque, C. A. et al. Genome sequence of the necrotrophic plant pathogen Pythium ultimum reveals original pathogenicity mechanisms and effector repertoire. Genome Biol. 11, 1–22 (2010).

Fry, W. Phytophthora infestans: the plant (and R gene) destroyer. Mol. Plant. Pathol. 9, 385–402 (2008).

El-Hissy, F. T., Khallil, A. M. & El-Nagdy, M. A. Fungi associated with some aquatic plants collected from freshwater areas at Assiut (upper Egypt). J. Islam Acad. Sci. 3, 298–304 (1990).

Uzuhashi, S., Okada, G. & Ohkuma, M. Four new Pythium species from aquatic environments in Japan. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 107, 375–391 (2015).

Nam, B. & Choi, Y. J. Phytopythium and Pythium species (Oomycota) isolated from freshwater environments of Korea. Mycobiology 47, 261–272 (2019).

Sparrow, F. K. Aquatic Phycomycetes (University of Michigan Press, 1960).

Johnson, T. W., Seymour, R. L. & Padgett, D. E. Biology and systematics of the Saprolegniaceae (2002).

Mahadevakumar, S. & Sridhar, K. R. Diagnosis of Pythium by classical and molecular approaches in Pythium: Diagnosis, Diseases and Management (eds. Rai, M., Abd-Elsalam, K. A. & Ingle, A. P.) 200–224 (CRC Press, 2020).

Rossmann, S., Lysøe, E., Skogen, M., Talgø, V. & Brurberg, M. B. DNA metabarcoding reveals broad presence of plant pathogenic Oomycota in soil from internationally traded plants. Front. Microbiol. 12, 637068 (2021).

Savian, F., Marroni, F., Ermacora, P., Firrao, G. & Martini, M. A metabarcoding approach to investigate fungal and Oomycota communities associated with Kiwifruit vine decline syndrome in Italy. Phytobiomes J. 6, 290–304 (2022).

Redekar, N. R., Eberhart, J. L. & Parke, J. L. Diversity of Phytophthora, Pythium, and Phytopythium species in recycled irrigation water in a container nursery. Phytobiomes J. 3, 31–45 (2019).

Jiang, R. H. Y. & Tyler, B. M. Mechanisms and evolution of virulence in Oomycota. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 50, 295–318 (2012).

Jiang, R. H. Y. et al. Distinctive expansion of potential virulence genes in the genome of the Oomycota fish pathogen Saprolegnia parasitica. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003272 (2013).

Fiore-Donno, A. M. & Bonkowski, M. Different community compositions between obligate and facultative Oomycota plant parasites in a landscape-scale metabarcoding survey. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 57, 245–256 (2021).

Nechwatal, J., Wielgoss, A. & Mendgen, K. Diversity, host, and habitat specificity of Oomycota communities in declining Reed stands (Phragmites australis) of a large freshwater lake. Mycol. Res. 112, 689–696 (2008).

Wielgoss, A., Nechwatal, J., Bogs, C. & Mendgen, K. Host plant development, water level and water parameters shape Phragmites australis-associated Oomycota communities and determine Reed pathogen dynamics in a large lake. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 69, 255–265 (2009).

Sakaguchi, S. O. et al. Molecular identification of water molds (Oomycota) associated with Chum salmon eggs from hatcheries in Japan and possible sources of their infection. Aquac Int. 27, 1739–1749 (2019).

Ahadi, R., Bouket, A. C., Alizadeh, A., Masigol, H. & Grossart, H. P. Globisporangium tabrizense sp. nov., Globisporangium mahabadense sp. nov., and Pythium bostanabadense sp. nov. (Oomycota), three new species from Iranian aquatic environments. Sci. Rep. 14, 31701 (2024).

Abdelzaher, H. M. A., Ichitani, T. & Elnaghy, M. A. Virulence of Pythium spp. isolated from pond water. Mycoscience 35, 429–432 (1994).

Kageyama, K. et al. Plant Pathogenic Oomycota Inhabiting River Water Are a Potential Source of Infestation in Agricultural Areas in River Basin Environment: Evaluation, Management and Conservation (eds. Li, F., Awaya, Y., Kageyama, K. & Wei, Y.) 261–288 (Springer, 2022).

Schenk, A. Algologische Mittheilungen. Verh Phys. Med. Ges Würzbg. 9, 12–31 (1859).

Vanterpool, T. C. & Ledingham, G. A. Studies on “browning” root rot of cereals: I. The association of Lagena radicicola n. gen.; n. sp., with root injury of wheat. Can. J. Res. 2, 171–194 (1930).

Truscott, J. H. L. Observations on Lagena radicicola. Mycologia 25, 263–265 (1933).

Macfarlane, I. Lagena radicicola and Rhizophydium graminis, two common and neglected fungi. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 55, 113–416 (1970).

Cerri, M. et al. Oomycota communities associated with Reed die-back syndrome. Front. Plant. Sci. 8, 1550 (2017).

Thines, M. & Buaya, A. T. Lagena—an overlooked Oomycota genus with a wide range of hosts. Mycol. Prog. 21, 66 (2022).

Van West, P. Saprolegnia parasitica, an Oomycota pathogen with a fishy appetite: new challenges for an old problem. Mycologist 20, 99–104 (2006).

Masigol, H. et al. Advancements, deficiencies, and future necessities of studying Saprolegniales: A semi-quantitative review of 1073 published papers. Fungal Biol. Rev. 46, 100319 (2023).

Hulvey, J. P., Padgett, D. E. & Bailey, J. C. Species boundaries within Saprolegnia (Saprolegniales, Oomycota) based on morphological and DNA sequence data. Mycologia 99, 421–429 (2007).

Pires-Zottarelli, C. L. A., de Oliveira Da Paixão, S. C., da Silva Colombo, D. R., Boro, M. C. & de Jesus, A. L. Saprolegnia atlantica sp. nov. (Oomycota, Saprolegniaceae) from Brazil, and new synonymizations and epitypifications in the genus Saprolegnia. Mycol. Prog. 21, 41 (2022).

Grossart, H. P. et al. Top-down and bottom‐up induced shifts in bacterial abundance, production and community composition in an experimentally divided humic lake. Environ. Microbiol. 10, 635–652 (2008).

Scholtysik, G. et al. Geochemical focusing and sequestration of manganese during eutrophication of lake Stechlin (NE Germany). Biogeochemistry 151, 313–334 (2020).

Perkins, A. K. et al. Highly diverse fungal communities in carbon-rich aquifers of two contrasting lakes in Northeast Germany. Fungal Ecol. 41, 116–125 (2019).

Allgaier, M. & Grossart, H. P. Seasonal dynamics and phylogenetic diversity of free-living and particle-associated bacterial communities in four lakes in Northeastern Germany. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 45, 115–128 (2006).

Pavić, D. et al. Variations in the sporulation efficiency of pathogenic freshwater Oomycota in relation to the Physico-Chemical properties of natural waters. Microorganisms 10, 520 (2022).

Meinelt, T. et al. Reduction in vegetative growth of the water mold Saprolegnia parasitica (Coker) by humic substance of different qualities. Aquat. Toxicol. 83, 93–103 (2007).

Masigol, H. et al. The contrasting roles of aquatic fungi and Oomycota in the degradation and transformation of polymeric organic matter. Limnol. Oceanogr. 64, 2662–2678 (2019).

Masigol, H. et al. Phylogenetic and functional diversity of Saprolegniales and Fungi isolated from temperate lakes in Northeast Germany. J. Fungi. 7, 968 (2021).

Semenov, M. V. Metabarcoding and metagenomics in soil ecology research: achievements, challenges, and prospects. Biol. Bull. Rev. 11, 40–53 (2021).

Auer, L. et al. Metatranscriptomics sheds light on the links between the functional traits of fungal guilds and ecological processes in forest soil ecosystems. New. Phytol. 242, 1676–1690 (2024).

Schlatter, D. C., Burke, I. & Paulitz, T. C. Succession of fungal and Oomycota communities in glyphosate-killed wheat roots. Phytopathology 108, 582–594 (2018).

Dickie, I. A. et al. Oomycota along a 120,000 year temperate rainforest ecosystem development chronosequence. Fungal Ecol. 39, 192–200 (2019).

Lang-Yona, N. et al. Species richness, rRNA gene abundance, and seasonal dynamics of airborne plant-pathogenic Oomycota. Front. Microbiol. 9, 2673 (2018).

da Silva, N. J. et al. Spatio-temporal drivers of different Oomycota beta diversity components in Brazilian rivers. Hydrobiologia 848, 4695–4712 (2021).

Masigol, H., Mostowfizadeh-Ghalamfarsa, R. & Grossart, H. P. The current status of Saprolegniales in Iran: calling mycologists for better taxonomic and ecological resolutions. Mycol. Iran. 8, 1–13 (2021).

Wang, Q. & Wang, X. Comparison of methods for DNA extraction from a single chironomid for PCR analysis. Pak J. Zool. 44, 421–426 (2012).

Schloss, P. D. et al. Introducing Mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 7537–7541 (2009).

Rognes, T., Flouri, T., Nichols, B., Quince, C. & Mahé, F. VSEARCH: a versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ 4, e2584 (2016).

Nelson, M. C., Morrison, H. G., Benjamino, J., Grim, S. L. & Graf, J. Analysis, optimization and verification of Illumina-generated 16S rRNA gene amplicon surveys. PLoS One. 9, e94249 (2014).

Uzuhashi, S., Kakishima, M. & Tojo, M. Phylogeny of the genus Pythium and description of new genera. Mycoscience 51, 337–365 (2010).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020). https://www.R-project.org

Weiner, J. riverplot: Sankey or Ribbon Plots. R package version 0.10. (2021). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=riverplot

Freudenthal, J., Dumack, K., Schaffer, S., Schlegel, M. & Bonkowski, M. Algae-fungi symbioses and bacteria-fungi co-exclusion drive tree species-specific differences in canopy bark microbiomes. The ISME Journal 18(1), p.wrae206 (2024).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer, 2016).

Hsieh, T. C., Ma, K. H. & Chao, A. Interpolation and extrapolation for species diversity. R Package Version 2.0.20 (2020). http://chao.stat.nthu.edu.tw/wordpress/software-download

Oksanen, J. et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.6-4. (2022). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan

Chen, H. VennDiagram: Generate High-Resolution Venn and Euler Plots. R package version 1.7.3. (2022). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=VennDiagram

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 1–21 (2014).

Foster, Z. S. L., Sharpton, T. J., Grünwald, N. J. Metacoder: An R package for visualization and manipulation of community taxonomic diversity data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005404 (2017).

Smither, M. L. & Jones, A. L. Pythium species associated with sour Cherry and the effect of P. irregulare on the growth of Mahaleb Cherry. Can. J. Plant. Pathol. 11, 1–8 (1989).

Masigol, H. et al. Notes on Dictyuchus species (Stramenopila, Oomycota) from Anzali lagoon, Iran. Mycol. Iran. 5, 79–89 (2018).

Walsh, P.S., Metzger, D.A. and Higuchi, R., 2013. Chelex 100 as a medium for simple extraction of DNA for PCR-based typing from forensic material. Biotechniques, 54, 134–139 (2013).

White, T.J., Bruns, T., Lee, S.J.W.T. & Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics in PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications (ed. Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J. & White, T.J.) 315–322 (Academic Press, 1990).

Hall, T. A. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic acids Symp. Ser. 41, 95–98 (1999).

De Cock, A. et al. Phytopythium: molecular phylogeny and systematics. Persoonia-Molecular Phylogeny Evol. Fungi. 34, 25–39 (2015).

Jankowiak, R., Stepniewska, H. & Bilanski, P. Notes on some Phytopythium and Pythium species occurring in oak forests in Southern Poland. Acta Mycol. 50, 1052 (2015).

Katoh, K., Rozewicki, A. & Yamada, K. D. MAFFT online service: multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief. Bioinform. 20, 1160–1166 (2019).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G. & Tamura, K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874 (2016).

Stamatakis, A. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22, 2688–2690 (2006).

Silvestro, D. & Michalak, I. RaxmlGUI: a graphical front-end for RAxML. Org. Divers. Evol. 12, 335–337 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by IGB Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries under DFG project Pycnocline (GR1540/37‐1). M.D.S. and M.B. acknowledge funding by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, FOR 5000, The Jena Experiment). Reyhaneh Shokati Marzdashti was removed as a co-author because the planned experiment could not be completed. And as a result, she was unable to contribute to the manuscript. However, the fact that the experiment remained incomplete was due to circumstances beyond her control and not a reflection of her efforts or commitment.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.M., H.P.G., and R.M.Gh. contributed to the conception of the study. H.M., S.P.T.H., and H.P.G. designed the work. H.M., M.D.S., R.A., S.R.T., and S.P.T.H. contributed to the acquisition of the data. M.D.S., H.M., and M.J.P. analyzed the data. H.M., M.D.S., and R.M.Gh. interpreted the data. M.D.S. and M.J.P. generated figures. M.D.S. conducted the bioinformatics and statistical analyses. H.M. and M.D.S. drafted major parts of the manuscript. All authors contributed to finalizing the draft of the manuscript. H.P.G., M.B., and R.M.Gh. supervised the study. H.P.G. and M.B. provided financial support for conducting the experiments and sequencing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Masigol, H., Solbach, M.D., Pourmoghaddam, M.J. et al. A glimpse into Oomycota diversity in freshwater lakes and adjacent forests using a metabarcoding approach. Sci Rep 15, 19124 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01727-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01727-3