Abstract

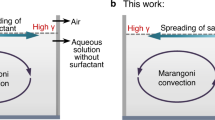

Preferential salt deposition and spreading influence both natural processes and industrial applications. This study examines salt deposition patterns in evaporating sessile drops and within capillary menisci above a brine pool. Temperature- and concentration-dependent surface tension induces Marangoni flow, which transports high-concentration liquid to the cooler side of the droplet where nuclei form and grow. Substrates with mixed thermal diffusivities and externally imposed thermal gradients can alter salt deposition patterns by controlling the direction of Marangoni flow. When connected to a brine pool, salt deposition creates a salt coating that can spread on vertical substrates. Spreading begins when crystals remain confined against the substrate: small crystals nucleating higher in the transition zone of capillary menisci have a higher likelihood of staying in place due to larger capillary forces. Salt spreading on a vertical substrate can be halted by imposing a downward thermal gradient to reverse the Marangoni flow direction within the capillary menisci or by engineering the surface roughness to reduce wettability. Horizontally roughened surfaces impede salt spreading; vertically roughened surfaces see the formation of stable crystals within short induction times, followed by rapid spreading as corner flow facilitates solution transport along interconnected roughness and through the porous salt coating.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is preferential evaporation near the contact line between a wetting sessile droplet and a substrate1,2,3. The replenishment of evaporated water towards the contact line induces an outward radial flow within the droplet; then, in the presence of dissolved salts, preferential salt deposition takes place around the droplet edge (“coffee-ring effect”4,5,6,7).

Preferential deposition affects industrial and scientific applications, such as inkjet printing8,9, surface coating10,11, drug screening12, bio-material analysis13, and crystal fouling in microdevices and heat exchangers14,15,16,17. Attempts to suppress or reverse preferential deposition have involved the use of surfactants18,19, colloidal particles5,20,21, local changes in temperature22, controlled relative humidity23, and altered substrate wettability24.

Fluid flow and replenishment are driven by capillarity and the surface tension gradient created by non-uniform evaporation and ensuing changes in temperature or concentration (Marangoni effect25,26). Flow can be either radially inward and trigger internal precipitation, or radially outward to form a ring-like salt pattern17,27,28,29. Therefore, controlling Marangoni flow can allow us to manipulate the salt deposition pattern.

Furthermore, the precipitated salts can gradually expand and spread on substrates if the front remains in contact with a reservoir. This phenomenon often called “salt creeping”30 is herein termed “salt spreading” to distinguish it from mechanical creep under sustained stress. While previous studies have explored underlying brine transport and deposition processes30,31,32,33, the initiation and inhibition of salt spreading on solid surfaces remain unclear34.

This study explores the underlying mechanisms for Marangoni flow within sessile drops, its effect on salt precipitation, the initiation and conditions for salt spreading, and potential control strategies to counteract preferential salt deposition and spreading.

Experimental studies

Sessile drops: hybrid substrates and thermal gradients

We prepared a 5.5 mol/L sodium chloride NaCl solution (Note the saturation concentration of NaCl is 6.1 mol/L at room temperature and pressure). We then placed 30 μL sessile drops on selected substrates using a pipette (89079-968, VWR Signature).

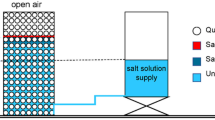

We controlled the substrate temperature gradient using active and passive methods. The active method imposed a thermal gradient by sitting one end of glass slides on a hot plate (Z645060, IKA RCT basic Ikamag—local temperatures measured using bonded thermocouples. See Supporting Information: experimental setup in Figure S1, and temperature data in Figure S2). The passive method involved hybrid substrates prepared with two surfaces of different thermal diffusivities (Fig. 1): a glass plate (microscope slides, Fisher Scientific Co., thermal diffusivity DT = 3.4 × 10−7 m2/s) and an aluminum plate (DT = 9.7 × 10−5 m2/s). To avoid differences in roughness and wettability, the two sections were coated with a thin layer of polytetrafluoroethylene (0.075 mm, Nexus Industries), and sessile drops were centered at the juncture of the glass and aluminum sections. Both active and passive tests were run at constant room temperature and relative humidity (T = 22 °C and RH = 56%). Time lapse photography recorded the evolution of evaporation and salt precipitation (Leica DMS300 microscope).

Figure 2a shows selected photographs of the sessile saline drop resting on the hybrid substrate: the salt crystal nucleates on the low thermal diffusivity glass plate (see Movie S1 in Supporting Information). Figure 2b shows the evaporation of a sessile saline drop on the glass slide subjected to a thermal gradient of 4.2 °C/cm: the salt crystal forms and deposits on the cooler side of the substrate (Movie S2 in Supporting Information). Duplicate tests systemically confirm the repeatability of these observations (Figure S3 in Supporting Information).

Evolution of a brine drop: evaporation and salt precipitation. (a) PTFE coated hybrid substrate made of glass and aluminum. (b) Homogeneous glass substrate with an imposed thermal gradient of 4.2 °C/cm. Salt precipitation starts on the cooler left side in both cases. The contact angle between brine and the PTFE substrate is ~ 110°. See time lapse Movies S1 and S2 in Supporting Information.

Salt spreading on glass rods

Glass rods (Fisherbrand™) were partially immersed in an open beaker filled with saturated NaCl solution and held in a vertical position to examine the evolution of salt spreading. In some cases, we added a heat source at the top to cause a downward thermal gradient along the rod (setup see Figure S4 in Supporting Information).

Figure 3 shows sequential images of salt spreading on a smooth glass rod without an imposed thermal gradient. Initially, salt crystals form within the wetting meniscus and fall into the bulk solution during evaporation (see time lapse video Movie S3 in Supporting Information). Crystal formation-and-falling continues until a crystal adheres to the glass rod; then, salt precipitation begins to spread along the glass rod. We repeated each test three times and obtained similar results: the incubation time t until the first crystal remains attached to the unheated smooth glass rod surface is 655 min < t < 945 min and increases to 1404 min < t < 2928 min for top-end heated glass rod.

Salt spreading on a smooth glass rod at room temperature. (a) Initial state. (b) Crystals precipitate and fall into the bulk solution. (c) Eventually, a crystal remains trapped in the upper part of the meniscus and grows. (d) Salt spreading on the glass surface. See time lapse video Movie S3 in Supporting Information.

Analyses and discussion

The effect of thermal gradients on salt deposition patterns

The evaporation rate of a sessile drop depends on the local vapor pressure surrounding the drop, and it is influenced by factors such as temperature (Clapeyron effect), curvature of the liquid–vapor interface (Kelvin effect), and intermolecular forces between the liquid film and the substrate near the contact line35 (model in Deegan et al.1). Experimental and numerical results confirm a higher evaporation rate near the contact line in wetting fluids2,3,36,37.

Evaporation is endothermic, the water temperature decreases near the contact line, and affects the surface tension γ [mN/m] along the drop surface38,39:

where temperature is in T [K]. Note that the evaporation enthalpy of water is 44.2 kJ/mol at 20 °C40, whereas the enthalpy of crystallization for NaCl is -3.9 kJ/mol41. For a 30 µL drop of a 5.5 mol/L NaCl solution, approximately 74 J of energy is absorbed during water evaporation compared to only 0.64 J released during NaCl crystallization. Consequently, the temperature gradient created by evaporating drops on hybrid substrates (Fig. 1) is predominantly governed by water evaporation and the heat compensation provided by substrates with different thermal diffusivities (glass: DT = 3.4 × 10⁻7 m2/s; aluminum: DT = 9.7 × 10⁻5 m2/s).

Meanwhile, the salt concentration S [g/kg] in the liquid near the gas–liquid interface increases during evaporation and affects surface tension too39:

Consequently, fluid flows from the low surface tension on the hotter side, to the high surface tension on the cooler and saltier side.

Evaporation-induced changes in temperature and concentration explain salt deposition on the cooler glass side of the hybrid substrate (Fig. 2): the high thermal diffusivity on the aluminum side preserves room temperature while the low thermal diffusivity glass side experiences a temperature drop (Fig. 1). Substrates with an actively imposed thermal gradient experience a similar sequence of events and salt crystals form and deposit on the cooler side of the substrate (Fig. 2b and Movie S2 in Supporting Information).

Internal flow during evaporation

We used a suspension of polystyrene latex particles (polystyrene plain, PS010UM, Magsphere, specific gravity Gs = 1.05, mean diameter d = 20 μm, mass particles/mass water = 0.5%) to confirm internal flow and preferential particle accumulation within a drop resting on a substrate with an imposed thermal gradient (8.2 °C/cm). Initially, latex particles were homogenously dispersed within the drop; as evaporation progressed, latex particles migrated towards the cooler side (Movie S4 in Supporting Information).

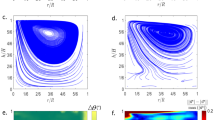

To gain internal information, we modelled two sessile saline drops (d = 5 mm) sitting on a glass substrate with two different thermal gradients, 4.2 °C/cm and 8.2 °C/cm (COMSOL Multiphysics—Navier–Stokes—Model details and parameters in Supporting Information). Results shown in Fig. 4 confirm that the temperature gradient along the drop surface drives a rotational flow field inside the drop. The maximum flow velocity is at the hot end and reaches 30 mm/s under the 4.2 °C/cm thermal gradient, and 80 mm/s for 8.2 °C/cm (reported values range from 0.01 mm/s to 110 mm/s42,43,44).

The significance of Marangoni convection

Internal fluid flow reflects the interplay between interfacial tension, viscous drag and heat diffusion. The capillary number Ca compares the resisting viscous drag and the driving surface tension gradient, while the Marangoni number Ma compares the rates of capillary convection and the dissipative effects (thermal diffusion and viscosity):

In terms of the dynamic viscosity μ [kg m−1 s−1], the characteristic flow velocity V [m/s], surface tension γ [N/m], and the characteristic length along the surface tension gradient L [m].

For example, consider a d = 5 mm diameter saline drop sitting on a substrate with a thermal gradient of 4.2 °C/cm so that the contact line temperature is Tcool = 37.2 °C on the cooler side and Twarm = 39.3 °C on the warmer side; the resulting surface tension difference is Δγ = 0. 33 mN/m (Eq. 1). The large Marangoni number Ma = 19,000 and the small capillary number Ca = 0.0007 (L = π × d/2 = 7.8 mm, DT = 1.58 × 10–7 m2/s and μ = 0.878 × 10–3 kg m−1 s−1) confirm the dominance of Marangoni convection near the liquid–air interface.

Salt spreading initiation: precipitate attachment

Crystallization on partially immersed vertical rods always initiates within the upward wetting meniscus (Fig. 3). There are three regions in the meniscus45 (Fig. 5a: (1) the upper thin film region where glass strongly attracts the water molecules and evaporation is minimal, (2) the transition region where capillary forces dominate, and (3) the bulk fluid region where the curvature is nearly constant and gravity forces dominate. Evaporation is most pronounced in the transition region (see model in Panchamgam et al.36, see also Plawsky et al.46 and Nguyen et al.47). In agreement with the sessile drop analyses, non-uniform evaporation induces temperature, concentration and surface tension gradients, leading to upward Marangoni flow and a locally high concentration that promotes salt crystallization near the meniscus upper region (Fig. 5b). Once a crystal adheres to the glass rod, pores between crystals and the substrate act as capillary conduits for salt solution transport and facilitate salt spreading on the glass rods30,31,32 (see formation of porous salt crusts in Dai et al.48).

Capillary meniscus. (a) Various regions and evaporative heat flux profile (after Plawsky et al.45). (b) Non-heated rod: Marangoni flow and precipitation. (c) Top heated rod: counter Marangoni flow. Sketched crystals suggest preferential precipitation.

Experimental observations show that the attachment of salt crystals onto the solid substrate is a precondition for the initiation of salt spreading. NaCl precipitates into cubic crystals under quiescent conditions49. The photograph in Fig. 6a shows a vertical view of a cubic salt crystal resting on a flat vertical substrate. Figures 6b and 6c identify the forces involved: the buoyant self-weight W, the effective force N normal to the wall, the shear resistance F, the force caused by the capillary suction \(\overline{U }\) = l2Δu = l2ρw⋅g·hc,and the perimetral force P ~ 3 l·γ created by the surface tension itself γ. The perimetral force P exceeds the force \(\overline{U }\) for small crystals l < 1 mm (for a capillary rise hc≈2 cm). The frictional shear resistance F = μf ·N depends on the friction coefficient μf between the crystal and the glass substrate which can range from μf = 0.1 to 0.750,51. It follows from this analysis that small crystals that nucleate higher in the transition zone benefit from the higher capillary force \(\overline{U }\) + P pressing them against the substrate and have a higher probability of remaining in place to initiate salt spreading.

Preventing salt spreading

Results with the top-heated smooth glass rod confirmed that reversing the Marangoni flow direction within the meniscus prevents nuclei formation and salt spreading (Fig. 5c). It is also known that surface roughness affects wettability52,53,54,55. In fact, anisotropic surface roughness renders different contact angles in orthogonal directions as observed with a sessile drop (Fig. 7a). Then, how does roughness affect salt spreading?

Effect of surface roughness anisotropy. (a) Drop sitting on a substrate with anisotropic roughness—grooves align in the A-direction: top and horizontal normal views. The advancing and receding contact angles along the grooves A-direction: \({\theta }_{adv}^{A}\) = 73° and \({\theta }_{rec}^{A}\) = 31°; along B-direction orthogonal to the grooves: \({\theta }_{adv}^{B}\) = 106° and \({\theta }_{rec}^{B}\) = 69°. (b) Salt spreading: I = horizontal roughness and II = longitudinal roughness. See time lapse video of salt spreading on glass rods in Supporting Information—Movie S5. Note: for visualization purposes, the two rods shown in this figure and in Movie S5 are immersed in the same brine pool and have the same starting time; however, the reported induction times were measured using rods inserted in separate pools to avoid interference. Still, there is very limited coupling in this figure: the distance between the two rods is ~ 20 mm, thus, the diffusion-controlled interaction time would be ~ 4500 min, which is significantly longer than the measured induction times (assumed diffusion coefficient ~ 1.5 × 10−9 m2/s).

We polished glass rods with #400 emery paper either horizontally along the circumferential direction, or vertically along the longitudinal direction (CarbiMet Plain #400—Buehler Ltd. Note: while the grit size is ~ 40 μm, the prevalent inter-groove distance observed on the glass substrates is ~ 100 μm). There were pronounced differences in induction times: vertically polished rods = 80-to-144 min, smooth glass rods = 655-to-945 min, horizontally polished rods = 1383-to-2673 min. Furthermore, Fig. 7b shows significant salt spreading on the vertically roughened glass rod but no salt spreading on the horizontally roughened rod (Note: for visualization purposes, Fig. 7 and the Movie S5 show the two rods immersed in the same brine pool and with the same starting time. The reported induction times were measured using rods inserted in separate pools to avoid any potential interference). Vertically aligned roughness grooves reduce the apparent contact angle (Fig. 7a), increase capillary rise, facilitate corner flow, and promote faster evaporation away from the brine pool. As a result, vertical roughness enhances salt spreading56,57,58.

Conclusions

This study explored salt deposition patterns in evaporating sessile drops and within the capillary meniscus above a brine pool. Furthermore, we engineered substrates with different thermal diffusivities and anisotropic surface roughness, and imposed thermal gradients to affect deposition. Salient results follow.

Marangoni flow transports liquids from regions with high temperature and low surface tension to regions with low temperature and high surface tension. The formation of a localized high concentration zone on the cooler side of the drop facilitates nuclei formation and crystal growth, increases surface tension further, and enhances Marangoni flow. Therefore, salt precipitation during the evaporation of sessile saline drops can be biased by engineered hybrid substrates with distinct thermal diffusivities or by imposing a thermal gradient on the substrate.

Marangoni flow triggered by evaporative cooling and increased concentration can sustain salt spreading on capillary menisci. Spreading starts when precipitated crystals remain against the substrate surface. Small crystals that nucleate higher in the transition zone of capillary menisci have a greater probability of remaining in place due to the larger capillary force that confines them against vertical substrates. The evolving salt layer is porous and provides capillary conduits for salt solution transport needed to sustain further salt precipitation and spreading. Corner flow facilitates solution transport, thus, spreading preferentially advances in the direction of interconnected roughness. Salt spreading can be prevented by imposing a downward thermal gradient or engineering the surface roughness to hinder wettability.

The insights gained from this study hold promise for controlling salt deposition patterns and spreading on solid substrates, with potential applications in various engineering and industrial contexts.

Data availability

Data will be made available upon request.

References

Deegan, R. D. et al. Contact line deposits in an evaporating drop. Phys. Rev. E 62, 756–765 (2000).

Erbil, H. Y. Evaporation of pure liquid sessile and spherical suspended drops: A review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 170, 67–86 (2012).

Larson, R. G. Transport and deposition patterns in drying sessile droplets. AIChE J. 60, 1538–1571 (2014).

Weon, B. M. & Je, J. H. Capillary force repels coffee-ring effect. Phys. Rev. E 82, 015305 (2010).

Yunker, P. J., Still, T., Lohr, M. A. & Yodh, A. G. Suppression of the coffee-ring effect by shape-dependent capillary interactions. Nature 476, 308–311 (2011).

Mampallil, D. & Eral, H. B. A review on suppression and utilization of the coffee-ring effect. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 252, 38–54 (2018).

Efstratiou, M., Christy, J. & Sefiane, K. Crystallization-driven flows within evaporating aqueous saline droplets. Langmuir 36, 4995–5002 (2020).

Friederich, A., Binder, J. R. & Bauer, W. Rheological control of the coffee stain effect for inkjet printing of ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 96, 2093–2099 (2013).

Kuang, M., Wang, L. & Song, Y. Controllable printing droplets for high-resolution patterns. Adv. Mater. 26, 6950–6958 (2014).

Layani, M. et al. Transparent conductive coatings by printing coffee ring arrays obtained at room temperature. ACS Nano 3, 3537–3542 (2009).

Uchiyama, H., Shimaoka, D. & Kozuka, H. Spontaneous pattern formation based on the coffee-ring effect for organic–inorganic hybrid films prepared by dip-coating: effects of temperature during deposition. Soft Matter 8, 11318 (2012).

Takhistov, P. & Chang, H.-C. Complex stain morphologies. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 41, 6256–6269 (2002).

Martusevich, A. K. & Kamakin, N. F. Crystallography of biological fluid as a method for evaluating its physicochemical characteristics. Bull Exp Biol Med 143, 385–388 (2007).

Sastri, V. S. Challenges in Corrosion: Costs, Causes, Consequences, and Control. (John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, 2015).

Schoenitz, M., Grundemann, L., Augustin, W. & Scholl, S. Fouling in microstructured devices: A review. Chem. Commun. 51, 8213–8228 (2015).

McBride, S. A., Skye, R. & Varanasi, K. K. Differences between colloidal and crystalline evaporative deposits. Langmuir 36, 11732–11741 (2020).

McBride, S. A., Girard, H.-L. & Varanasi, K. K. Crystal critters: Self-ejection of crystals from heated, superhydrophobic surfaces. Sci Adv 7, eabe6960 (2021).

Anyfantakis, M., Geng, Z., Morel, M., Rudiuk, S. & Baigl, D. Modulation of the coffee-ring effect in particle/surfactant mixtures: the importance of particle-interface interactions. Langmuir 31, 4113–4120 (2015).

Seo, C., Jang, D., Chae, J. & Shin, S. Altering the coffee-ring effect by adding a surfactant-like viscous polymer solution. Sci. Rep. 7, 500 (2017).

Wong, T.-S., Chen, T.-H., Shen, X. & Ho, C.-M. Nanochromatography driven by the coffee ring effect. Anal. Chem. 83, 1871–1873 (2011).

Bhardwaj, R., Fang, X., Somasundaran, P. & Attinger, D. Self-assembly of colloidal particles from evaporating droplets: Role of DLVO interactions and proposition of a phase diagram. Langmuir 26, 7833–7842 (2010).

Soltman, D. & Subramanian, V. Inkjet-printed line morphologies and temperature control of the coffee ring effect. Langmuir 24, 2224–2231 (2008).

Bou Zeid, W. & Brutin, D. Influence of relative humidity on spreading, pattern formation and adhesion of a drying drop of whole blood. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 430, 1–7 (2013).

Patil, N. D., Bange, P. G., Bhardwaj, R. & Sharma, A. Effects of substrate heating and wettability on evaporation dynamics and deposition patterns for a sessile water droplet containing colloidal particles. Langmuir 32, 11958–11972 (2016).

Buffone, C., Sefiane, K. & Christy, J. R. E. Experimental investigation of self-induced thermocapillary convection for an evaporating meniscus in capillary tubes using micro–particle image velocimetry. Phys. Fluids 17, 052104 (2005).

Hu, H. & Larson, R. G. Marangoni effect reverses coffee-ring depositions. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 7090–7094 (2006).

Ristenpart, W. D., Kim, P. G., Domingues, C., Wan, J. & Stone, H. A. Influence of substrate conductivity on circulation reversal in evaporating drops. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 234502 (2007).

Gambaryan-Roisman, T. Modulation of Marangoni convection in liquid films. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 222, 319–331 (2015).

Lama, H., Satapathy, D. K. & Basavaraj, M. G. Modulation of central depletion zone in evaporated sessile drops via substrate heating. Langmuir 36, 4737–4744 (2020).

Hazlehurst, T. H., Martin, H. C. & Brewer, L. The creeping of saturated salt solutions. J. Phys. Chem. 40, 439–452 (1936).

Washburn, E. R. The creeping of solutions. J. Phys. Chem. 31, 1246–1248 (1927).

van Enckevort, W. J. P. & Los, J. H. On the creeping of saturated salt solutions. Cryst Growth Des 13, 1838–1848 (2013).

Hird, R. & Bolton, M. D. Upward migration of sodium chloride by crystallization on non-porous surfaces. Phil. Mag. 94, 78–91 (2014).

Qazi, M. J., Salim, H., Doorman, C. A. W., Jambon-Puillet, E. & Shahidzadeh, N. Salt creeping as a self-amplifying crystallization process. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax1853 (2019).

DasGupta, S., Kim, I. Y. & Wayner, P. C. Use of the Kelvin-Clapeyron equation to model an evaporating curved microfilm. J. Heat Transfer 116, 1007–1015 (1994).

Panchamgam, S. S., Chatterjee, A., Plawsky, J. L. & Wayner, P. C. Comprehensive experimental and theoretical study of fluid flow and heat transfer in a microscopic evaporating meniscus in a miniature heat exchanger. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 51, 5368–5379 (2008).

Deegan, R. D. et al. Publisher Correction: Capillary flow as the cause of ring stains from dried liquid drops. Nature 592, E12–E12 (2021).

IAPWS. Revised Release on Surface Tension of Ordinary Water Substance. International Association for the Properties of Water and Steam http://www.iapws.org/relguide/Surf-H2O.html (2014).

Nayar, K. G., Sharqawy, M. H., Banchik, L. D. & Lienhard, V. Thermophysical properties of seawater: A review and new correlations that include pressure dependence. Desalination 390, 1–24 (2016).

Zhu, H. et al. Thermodynamics of crystal formation and growth in a sessile droplet. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 5, 101971 (2024).

Armstrong Green, N. C. et al. Studies of the crystallization and dissolution of individual suspended sodium chloride aerosol particles. J. Phys. Chem. A 128, 4315–4323 (2024).

Hegseth, J. J., Rashidnia, N. & Chai, A. Natural convection in droplet evaporation. Phys. Rev. E 54, 1640–1644 (1996).

Hu, H. & Larson, R. G. Analysis of the microfluid flow in an evaporating sessile droplet. Langmuir 21, 3963–3971 (2005).

van Gaalen, R. T., Diddens, C., Wijshoff, H. M. A. & Kuerten, J. G. M. Marangoni circulation in evaporating droplets in the presence of soluble surfactants. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 584, 622–633 (2021).

Plawsky, J. L., Ojha, M., Chatterjee, A. & Wayner, P. C. Review of the effects of surface topography, surface chemistry, and fluid physics on evaporation at the contact line. Chem. Eng. Commun. 196, 658–696 (2008).

Plawsky, J. L. et al. Nano- and microstructures for thin-film evaporation—a review. Nanoscale Microscale Thermophys. Eng. 18, 251–269 (2014).

Nguyen, T. T. T. et al. Spontaneously oscillating menisci: Maximizing evaporative heat transfer by inducing condensation. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 128, 137–148 (2018).

Dai, S., Shin, H. & Santamarina, J. C. Formation and development of salt crusts on soil surfaces. Acta Geotech 11, 1103–1109 (2016).

Adams, J. M. & Pritchard, R. G. The crystal structure of 4Na 2 SO 4.2H 2 O 2.NaCl. Acta Crystallogr. B 34, 1428–1432 (1978).

Buckley, D. H. Friction, Wear, and Lubrication in Vacuum. vol. 277 (National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, D.C., 1971).

Bird, J. O. & Chivers, P. J. Newnes Engineering and Physical Science Pocket Book. (Elsevier, 1993). https://doi.org/10.1016/C2013-0-06543-7.

Wenzel, R. N. Resistance of solid surfaces to wetting by water. Ind. Eng. Chem. 28, 988–994 (1936).

Ye, Z. & Mizutani, M. Apparent contact angle of curved and structured surfaces. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp 677, 132337 (2023).

Cassie, A. B. D. & Baxter, S. Wettability of porous surfaces. Trans. Faraday Soc. 40, 546 (1944).

Danish, M. Contact Angle Studies of Hydrophobic and Hydrophilic Surfaces. in Handbook of Magnetic Hybrid Nanoalloys and their Nanocomposites 761–782 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-90948-2_24.

Cardona, A. & Santamarina, J. C. Immiscible imbibition in fractured media: A dual-porosity microfluidics study. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 170, 105555 (2023).

Dong, M. & Chatzis, I. The imbibition and flow of a wetting liquid along the corners of a square capillary tube. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 172, 278–288 (1995).

Dullien, F. A. L. Porous Media. (Elsevier, 1979). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-223650-1.X5001-3.

Acknowledgements

Support for this research was provided by the KAUST Endowment at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, and the GW Clough endowment at Georgia Tech. Gabrielle. E. Abelskamp edited earlier versions of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have contributed substantially to the manuscript and approved the final submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xia, Z., Liu, Q. & Santamarina, J.C. Controlling salt deposition patterns using engineered substrates and thermal gradients. Sci Rep 15, 18922 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01772-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01772-y