Abstract

The photovoltaic (PV) energy is essential for the future of sustainable energy developments. Conventional algorithms perform well in maximum power extraction under uniform irradiance conditions (UIC). However, they often struggle to maintain the global maximum power point (GMPP) under simple partial shading conditions (SPSCs), frequently getting stuck at local maximum power points (LMPPs) and resulting in power loss. This study developed an adapted perturb and observe based model predictive control (APO-MPC) maximum power point tracking (MPPT) approach in MATLAB/Simulink, comprising six series-connected PV modules, a boost converter, and load. The control strategy identifies GMPP and computes reference current to minimize the cost function of an optimization problem. It was compared with other MPPT algorithms regarding tracking accuracy, convergence speed, computational time, steady-state oscillations (SSOs), power efficiency under UIC, SPSCs, and complex partial shading conditions (CPSCs). The system was validated using real-time hardware implementation and seasonal field atmospheric data. The results indicated that the APO-MPC algorithm outperformed the others with no oscillations during GMPP tracking, average convergence time, and tracking efficiency of 0.17 s and 99.46%, respectively. The findings confirm its highly fast, accurate, and stable tracking of GMPP without getting trapped into LMPPs under CPSCs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Photovoltaic (PV) energy has attracted global attention due to the effects of climate change, decaying fossil fuels, and rising electricity costs. With the implementation of new PV technologies, its installation cost has significantly decreased, making it a more affordable option for energy generation. In real climate, PV arrays can be shaded by nearby trees, buildings, clouds, and other obstacles, leading to non-uniform irradiance distribution known as partial shading condition (PSC). When PSC occurs, the PV array displays multiple power point peaks, including various local maximum power points (LMPPs) and a single global maximum power point (GMPP). This results in PV modules being unable to achieve their optimal operating point consistently and affects its overall performance efficiency1. Thus, the efficient maximum power point technique (MPPT) is crucial for enhancing solar energy utilization under dynamic climate profiles. PV energy provides an alternate solution to Pakistan’s energy crisis, which includes a growing energy shortage, limited oil reserves, and inconsistent utility grid infrastructure. In addition to standalone PV applications, the integration of solar PV with grid-based virtual power plants (VPP) has been explored as a means to optimize energy scheduling and enhance grid reliability2. Such approaches, when combined with advanced MPPT techniques, can contribute to more stable and efficient energy distribution. A significant proportion of oil is imported from oil-rich nations, leading to substantial expenditure on oil importation. It not only resolves the energy crisis but also has the ability to create jobs, promote local manufacturing, and enhance economic growth3. Pakistan’s diverse topography and climate profiles create favorable conditions for solar energy installation. Many regions across the country enjoy abundant sunlight yearly, with an average irradiance of 6.5 kW/m²4.

In literature, various traditional MPPT algorithms such as perturb and observe (PO)5, adapted perturb and observe (APO)6, incremental conductance (IC)7, modified incremental conductance (MIC)8, improved incremental conductance (IIC)9, and constant voltage technique (CVT)10 are utilized to track optimal point of PV systems; however, these algorithms are not suitable under PSCs and dynamic weather conditions11,12. Although these methods have simplified computations and easy installation, they may fall towards the LMPPs and exhibit overshoots and steady-state oscillations (SSOs) but are still used in most commercial controllers13,14. Therefore, various algorithms, including PO, APO, IC, MIC, and IIC are selected as they are widely used in PV systems due to their simplicity, easy installation, and availability of extensive literature on performance across diverse environmental conditions. Comparing the proposed methodology with these algorithms provides a thorough performance evaluation to assess their strengths and limitations under static and dynamic conditions for practical implementation in real-world applications. Some intelligent techniques such as fuzzy logic controller (FLC)15, voltage control method (VCM)16, artificial neural network (ANN)17, and genetic algorithm (GA)18 are introduced to encounter these problems. However, these algorithms efficiently optimize the MPP under PSC with zero SSOs. However, they require a high computational burden and decrease convergence time due to complex calculations within the processing hierarchy. Recently, optimization-based algorithms such as particle swarm optimization (PSO)19, grey wolf optimization (GWO)20, sliding mode controller (SMC)21, and conventional model predictive control (CMPC)22 are implemented to address these issues and extract the MPP under PSC. An exponential forgetting recursive least squares method updates proportional integral derivative gains online using Lyapunov synthesis for tracking GMPP dynamically. The proposed algorithm minimizes convergence time, resulting in faster settling, reduced oscillations, and a relative decrease in peak voltage in the PV module, ultimately enhancing the generated power23. However, it has some limitations, including overshoots in the transient response and oscillations around the MPP. In24, a voltage scanning-based approach which computes skipping voltages for locating GMPP is introduced for improving tracking speed and overall efficiency of PV system under PSCs. The performance was validated using four series panels and a boost converter under five different patterns of PSCs. The algorithm outperforms PSO, CSA, and GWO in terms of tracking speed and higher output power. But the algorithm exhibits transient oscillations before convergence to the optimal point which is its primary drawback. A linear active disturbance rejection control (LADRC) based adaptive particle swarm optimizer (APSO) algorithm is introduced to improve MPPT performance by adjusting inertia weights, reinitializing to find varying GMPP, and optimizing learning factors for faster, more accurate convergence25. A hybrid GWO based PSO algorithm utilizes meta-optimization scheme to increase the power generation by improving converter’s operation26. The validations are performed using real-time measured data and expressed significant performance compared to the PO, IC and PSO. However, the study claims transient and steady-state response breakdowns around MPP. A novel grey wolf optimization (NGWO) algorithm is proposed to enhance the operation of PV-BESS systems under PSCs, offering a promising solution to improve their efficiency in such challenging conditions27. Similarly, a horse herd optimization technique inspired by the movement patterns of horses within a herd is proposed under rapidly changing PSCs28. The algorithm highlights its robustness by outperforming other metaheuristic algorithms, however, tracking speed of 2.2 s and 1.91% power oscillations still require improvement. Therefore, many optimization-based algorithms have slow convergence, transient and steady-state breakdowns, significant oscillations around GMPP and most of the time fall into LMPPs. A nonlinear proportional-integral-derivative (NPID) controller integrated with a hybrid salp particle swarm optimization algorithm (SPSOA) is developed to efficiently track the GMPP with improved performance across varying conditions29. Thus, an MPPT technique based on a hybrid approach such as adapted perturb and observe based model predictive control (APO-MPC) has been introduced to enhance speed and GMPP tracking accuracy22. The comparative performance analysis with existing MPPT techniques is illustrated in Table 1. Based on the literature review, this study examines complex PSCs (CPSCs), which offer greater challenges for tracking optimal point. A system was implemented in MATLAB/Simulink, consisting of a PV array of six modules connected in a series configuration, a DC-DC boost converter, and a load. The algorithm was implemented and tested under various climate profiles such as uniform irradiance conditions (UIC), simple PSCs (SPSCs), CPSCs, and field atmospheric datasets. The algorithm was then evaluated and compared alongside other MPPT techniques such as PO, APO, IC, FLC, GWO and MPC using experimental validation based on criteria such as convergence speed, GMPP tracking, computational complexity, efficiency, oscillations, and overall performance. The key contributions of this paper are given as follows:

-

i.

Existing literature primarily focuses on implementing MPPT algorithms under SPSCs, this study explores more complex and dynamic shading scenarios. It integrates a real atmospheric dataset with high irradiance variability from Lahore’s PV station for experimental validation, ensuring a more realistic assessment of its performance.

-

ii.

Unlike conventional MPPT methods that suffer from high SSOs or slow convergence, APO-MPC ensures minimal power fluctuations while maintaining high tracking efficiency.

-

iii.

Simulation results show that the proposed method excels in GMPP tracking, achieving an average tracking efficiency of 99.46%, a fast convergence time of 0.17 s, an improved settling time of 0.24 s, and a 2–13% increase in power generation under three shading scenarios including UIC, SPSC, and CPSC compared to other techniques.

-

iv.

An experimental hardware setup was developed to validate the algorithm, demonstrating effective GMPP tracking with an average efficiency of 97.14% and stable output power in real-time conditions of UIC, SPSC, and CPSC.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section “PV Array Formation” describes the configuration of the PV array, projection components of solar irradiance, and its output characteristics under UIC, SPSCs, and CPSC. Section “Converter Parameters” provides the description and design parameters of the DC-DC boost converter. Section “Implementation of GMPP Tracker” explains the utilization of APO-MPC algorithm and its implementation scheme in PV system. Section “Results and Discussions” presents detailed simulation results and findings, including a comparison with other algorithms for performance validation. Additionally, it describes the hardware setup and evaluates real-time performance under varying shading conditions. Finally, the “Conclusion and Future Work” section summarizes the key outcomes and proposes directions for future research.

PV array formation

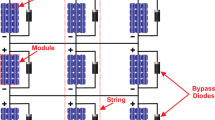

This study consists of a PV string formed by six modules connected in series, as depicted in Fig. 1. The PV array exhibits nonlinear behavior between the output current and voltage, leading to CPSCs, particularly under dynamic shading conditions. This shading can reverse bias the affected modules to act as loads instead of power producers and dissipate power in the form of heat. This reduces the output current and can cause hot spots, potentially resulting in permanent damage to the entire string. To mitigate this issue, bypass diodes D11-D23 are installed with each PV module, and a blocking diode (red colored) is used to prevent reverse current flow, which could further harm the PV array.

Design

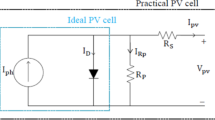

PV cells are typically made from semiconductor material, usually silicon. Each cell consists of a thin layer of n-type material and a thicker layer of p-type material, forming a p-n junction. When exposed to sunlight, free charge carriers move between energy bands to create a potential difference across the cell terminals and produce an electric current. This photocurrent of the PV module is modeled using the single-diode model, which accurately represents the output characteristics as illustrated in Fig. 222. The photovoltaic current Ipv of this model includes key components such as a photocurrent represented by the current source Iph, a diode current Id, and current Ip through parallel resistance Rp as illustrated in Eq. (1). The total output current Ipv including all variables of a cell is given by the Eq. (2).

where \(\:{G}_{a}\) is actual solar irradiance, \(\:{G}_{r}\) is reference solar irradiance at standard testing conditions (STC), \(\:{I}_{sc}\:\)is the short circuit current, \(\:{K}_{sc}\) is the temperature coefficient under the short circuit, \(\:{T}_{a}\) is actual atmospheric temperature, \(\:{T}_{r}\) is reference temperature at STC, \(\:{I}_{o}\:\)is the diode leakage current, \(\:{K}_{B}\) is the Boltzmann constant, \(\:q\:\)is the electronic charge, \(\:{D}_{i}\:\)is the diode ideality factor. The PV cells are configured in different series and parallel combinations to maximize the output power and configure a PV module. The output current of a PV module can be computed using Eq. (3).

where \(\:{N}_{p}\) is the number of cells connected in parallel and \(\:{N}_{s}\) is the number of cells connected in series within a module. Table 2 presents the parameters and characteristics of the used PV panels.

Shading effects

Solar irradiance denotes the amount of electromagnetic radiation in the form of power per unit area received from the Sun. It is an essential factor that affects the performance of PV panels. Figure 3 presents various components of the solar irradiance impacting the PV array inclined at an angle γ to the horizontal surface. Extraterrestrial irradiance (ETI) refers to the solar radiation received outside the Earth’s atmosphere. This measure is essential because it represents the maximum potential solar Energy that can be captured before the radiation interacts with the Earth’s atmosphere. Direct normal irradiance (DNI) is a key component of the total solar irradiance reaching Earth’s surface. It travels straight from the Sun to the observer and is responsible for casting sharp shadows. It plays a significant role in the total global irradiance captured by the panels. Diffuse irradiance (DI) refers to sunlight that has been scattered by the atmosphere and sometimes causes a partial shading effect23. Molecules, particles, water droplets, or atmospheric clouds can cause this scattering. Even during cloudy weather, PV panels still absorb diffused sunlight irradiance, indicating a considerable power loss.

Considering the PV array presented in Fig. 1 experiences different irradiance profiles for each module under CPSC, each module exhibits different I-V and P-V characteristic curves. To validate the effect of different shading patterns, uniform irradiance, SPSCs, and CPSC were established by assigning different irradiance levels to each PV module (M11, M12…, M23). The irradiance settings for these three patterns in case 1 are detailed in Table 3 which represents UIC with 1000 W/m2 irradiance on all modules in pattern 1, SPSC1 with 500, 750, and 1000 W/m2 on three pairs of PV modules in pattern 2, SPSC2 with 1000, 1000, 1000, 400, 600, and 200 W/m2 in pattern 3 and CPSC with 350, 500, 600, 750, 900, and 1000 W/m2 irradiance on each module in pattern 4. The study utilizes atmospheric data based on four seasons i.e. summer, winter, autumn, and spring, collected from a PV Station in Lahore City for real-time performance validation of the proposed methodology in case 2. The characteristics curves are presented in Fig. 4, where pattern 1 under UIC contains only one peak of GMPP, pattern 2 under SPSC1 presents one GMPP on the end of the P-V curve, and two LMPPs and pattern 3 under SPSC2 expresses one GMPP at the beginning and three LMPPs. Pattern 4 under CPSC exhibits five LMPPs and one GMPP in the middle.

Converter parameters

The MPPT control scheme adjusts the duty cycle to optimize the switching state of the DC-DC boost converter for stepping up the input voltage, as illustrated in Fig. 522. The duty cycle ranges between 0 and 1. The voltage ripples generated by the converter are mitigated using passive components, specifically capacitors or a parallel combination of capacitors and inductors31. In conduction mode, the input inductor Lin, input resistor Rin, source resistor Rs, and input capacitor Cin operate in series with Vpvas detailed in Eq. (4). Similarly, in cut-off mode, the input inductor Lin, input resistor Rin, source resistor Rs, output resistor Ro, input capacitor Cin, and output capacitor Co will operate in series with Vpv as expressed in Eq. (5).

The modeled parameters used by the converter can be derived by solving Eqs. (4) and (5) and provided in Table 4.

Implementation of GMPP tracker

Tracking of the GMPP is essential for maximizing the performance of PV systems. In areas having frequent cloudy climate profiles, PV modules often face shading effects due to dust, clouds, or nearby structures or trees. As a result, implementing a highly efficient MPPT approach is necessary for improving overall efficiency under diverse operating conditions. The implemented methodology integrates the APO technique with a modified MPC approach named APO-MPC. In this method, APO calculates the reference current using an appropriate variable step size (VSS). At the same time, MPC computes the duty cycle for optimizing the switching state of the converter to track the GMPP precisely.

APO-MPC algorithm

The conventional PO methods adjust the PV voltage by applying a fixed step size and modifying the output power accordingly. If the power increases, the controller adjusts in the same direction until the power stops rising. However, constant step size causes oscillations in the output power and overshoots in some cases. Additionally, it cannot effectively track power fluctuations during load changes or rapid variations in environmental conditions. The APO technique is an improved version of the conventional PO methods. It operates by systematically adjusting the PV system’s operating point and monitoring the resulting changes in power output until the MPP is reached. It employs VSS with a scaling factor of K based on the MPP position. The primary objective of this algorithm is to explicitly track the process and minimize the SSOs, thereby enhancing the overall efficiency of the PV system. Figure 6 illustrates the APO algorithm’s optimal point (OP) detection method by changing step positions i.e., Pos 1, Pos 2, ……., and Pos 6 for each cycle of operation. At the start of the algorithm, the operating voltage is set in an open-circuit state. This process involves large step sizes if the operating point is far from OP, such as at Pos 5 and Pos 6. Similarly, as the operating point reaches near OP, it reduces step sizes to eliminate fluctuations such as Pos 3 and 4. Additionally, when the difference between consecutive operating points becomes zero, the operation sequence will converge towards the OP, and the step size will reduce to zero simultaneously.

It functions in four stages i.e., perturbation, observation, reference current computation, and repetition, as shown in Algorithm 1. First, it detects the current and voltage for power computation across each module using Eq. (6). Next, using sequential combinations it compares the output power of each PV module with one another and identifies the shading effect using Eq. (8). Based on the comparison with each pair of PV modules, it determines the unique power vector Pu and counts its elements to define the number of shaded modules occurred using Eq. (8). If m modules are shaded out of n series-connected modules, the p number of power peaks will be equal to m. Next, it calculates the Vmp for the non-shaded PV modules, assuming the voltage across the shaded modules is Vd = 0.7 V, using Eq. (9). The approach uses Eq. (12) to identify GMPP out of the available power peaks within the PV characteristics. Then, it incorporates the value of an initialized reference current ΔIref (t) in Eq. (11) to produce a next interval value based on the operating point’s left or right position. When the difference between consecutive operating points becomes zero, the sequence converges toward the GMPP, with the step size gradually decreasing to zero.

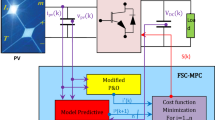

MPC generally operates by using a system model to forecast future behavior. This model helps determine a control input to minimize a cost function, which usually represents the discrepancy between the output and a reference value. Once the control input is calculated, it is implemented in the system to obtain the desired output. The schematic diagram of MPC implementation in the PV system is presented in Fig. 7. The optimal switching state is determined by evaluating the expected system response to control inputs. The flowchart of the APO-MPC algorithm is illustrated in Fig. 8. A prediction horizon allows it to predict future behavior and adjust actual output according to the reference trajectory. In contrast, the control horizon refers to the number of control steps calculated to optimize the system’s output. The optimal control action for the next step is chosen based on the predicted future conditions of the system using a one-step prediction method N = 1. A more extended control horizon enables it to plan for more future states, leading to improved performance, but it also requires greater computational resources to execute. Therefore, a single-step prediction horizon is selected which simplifies the cost function and the controller focuses on the immediate next step, enabling a fast response to rapid irradiance changes. Figure 9 depicts the prediction horizon from u(t) to u(t + N) and follows the reference trajectory smoothly from larger steps S1 to optimized steps S4. The generalized Eqs. (12) and (13) demonstrating the boost converter’s predictive model are extracted using Eqs. (4) and (5) for conduction and cut-off modes with S = 0 or 1. The components Rin, Rs, and Cin are omitted from these equations due to their negligible values, simplifying the system’s computational complexity.

The cost function is formulated by taking into account the future states, reference values, and expected control actions as given by Eq. (14). The control input that minimizes the cost function is obtained by solving an optimization problem, which is usually handled using a numerical method outlined in Eq. (15). Finally, the cost function utilized to optimize the switching state of the converter is given by Eq. (16).

Results and discussions

This section details the implementation of the APO-MPC algorithm using MATLAB Simulink and an experimental platform, following the schematic diagram shown in Fig. 5. The study compares and analyzes its performance with different approaches such as PO, APO, IC, MIC, IIC, and CMPC. The system consists of 6 PV modules connected in series to validate the simple and CPSCs. In case 1, pattern 1 contains UIC, pattern 2 considers SPSC1, pattern 3 presents SPSC2, and pattern 4 includes CPSC. For quantifying the power oscillations around OP, three values for power measurements after the GMPP is settled in the steady-state are taken, and the standard deviation is calculated using the expression given in Eq. (17). Similarly, pattern 5 comprises rapid variations from pattern 2 to pattern 4 and case 2 contains field historical data of Lahore, Pakistan. The technical parameters of both PV modules and boost converter are presented in Tables 2 and 4, respectively.

where \(\:\sigma\:\) is the standard deviation used for quantifying oscillations in steady-state, \(\:j\) is the number of maximum power measurements, \(\:{P}_{i}\) and \(\:{P}_{t}\) are maximum power values and tracked power, respectively.

Case 1

In this case, three UIC, SPSCs, and CPSC patterns are validated under an ambient temperature of 25 °C as presented in Table 3. The GMPPs for each irradiance pattern i.e. pattern 1 has 1499.05 W, pattern 2 has 833.33 W, pattern 3 has 732.46 W, and pattern 4 has 700.20 W as shown in Fig. 4. The comparison of output power tracked under pattern 1 is illustrated in Fig. 10. The PO method expressed fast convergence towards GMPP by attaining output power of 1394.38 W at 0.02 s with power efficiency of 93.01% and fluctuations of 44.93 W. The APO and IC algorithms take the longest to track the optimal point, attempting to converge towards the GMPP until 0.57 s and 0.87 s, respectively. Both algorithms have attained output power of 1431.78 W and 1437.41 W with power efficiency of 95.51% and 95.88%, respectively. The tracking time for MIC and IIC is 0.09 s and 0.12 s, which is comparatively better than APO and IC algorithms. However, these have achieved maximum power of 1450.58 W and 1475.54 W with power efficiency of 96.76% and 98.43%, respectively. Both algorithms illustrated power fluctuations of 46.57 W and 29.83 W, lower than the others. The CMPC and APO-MPC algorithms smoothly tracked GMPP at 0.46 s and 0.25 s by attaining the output power of 1477.45 W and 1493.66 W with power efficiency of 98.55% and 99.64%, respectively. However, CMPC has significant power oscillations till 0.52 s. As pattern 1 has only a unique peak point due to UIC, all seven techniques can track the GMPP effectively. Among these, APO-MPC demonstrates superior tracking accuracy and efficiency compared to the other six methods.

Tracking speed in MPPT technologies is evaluated using rise time and settling time during the GMPP convergence. The rise times for PO, APO, IC, MIC, IIC, CMPC, and APO-MPC are 0.01 s, 0.17 s, 0.27 s, 0.08 s, 0.12 s, 0.24 s, and 0.13 s, respectively, with corresponding settling times of 0.02 s, 0.58 s, 0.87 s, 0.09 s, 0.14 s, 0.52 s, and 0.21 s. The PO, MIC, IIC, and APO-MPC algorithms have the shortest rise time, under 0.15 s, and exhibit a quicker settling time. Other algorithms have taken longer to achieve convergence, leading to power loss and lower energy output from the PV array. Power oscillations and fluctuations around the GMPP can cause energy losses, particularly in PO, MIC, and IIC. The output characteristic curve of the PV array under pattern 2 exhibits three power points, with the power values at the two rightmost power points being quite similar, making the MPPT operation more challenging. The maximum power values are 833.33 W at 199.03 V, 787.86 W at 127.13 V, and 476.44 W at 59.70 V. The GMPP is located at 833.33 W on the extreme right peak. The comparison of output power tracked under pattern 2 is illustrated in Fig. 11. The PO method expressed fast convergence by falling into an LMPP. It attained an output power of 441.73 W at 0.06 s with power efficiency of 53% and fluctuations of 12.41 W. The APO and IC algorithms take the longest convergence time and attempt to converge until 0.57 s and 1.0 s respectively. Both algorithms have attained output power of 662.31 W and 813.11 W with power efficiency of 79.47% and 97.57%, respectively. The settling time for MIC and IIC is 0.09 s and 0.12 s, which is comparatively better than APO and IC algorithms. However, these have achieved maximum power of 764.10 W and 802.46 W with power efficiency of 91.69% and 96.29%, respectively. Both algorithms illustrated power fluctuations of 38.62 W and 19.30 W, more than the PO algorithm. The CMPC algorithm tracked GMPP at 0.44 s by attaining the output power of 814.05 W with a power efficiency of 97.68%. However, CMPC has shown significant power oscillations during rise time till 0.56 s. The APO-MPC algorithm has smoothly tracked the optimal power point at 0.23 s by extracting the output power of 828.45 W with a power efficiency of 99.41%. The rise times for PO, APO, IC, MIC, IIC, CMPC, and APO-MPC are 0.06 s, 0.19 s, 0.31 s, 0.07 s, 0.09 s, 0.21 s, and 0.14 s, respectively, with settling times of 0.07 s, 0.57 s, 1.0 s, 0.09 s, 0.11 s, 0.55 s, and 0.25 s. The power curve for pattern 2 is slightly more complex than that for pattern 1; therefore, only IIC, CMPC, and APO-MPC techniques can track the GMPP effectively. Among these, APO-MPC has superior power gain due to high tracking speed, absence of power oscillations, and close tracking of the GMPP, while IIC and CMPC experience lower power gain due to persistent power oscillations. Each module’s PV array subjected to non-uniform irradiance generates complex multi-peak clusters. In cluster 1, there are three extreme points with maximum power values of 700.20 W at 166.49 V, 659.36 W at 130.87 V, and 606.68 W at 206.17 V. Similarly, in cluster 2, the other three extreme points have maximum power values of 591.92 W at 94.05 V, 444.73 W at 61.06 V, and 221.23 W at 26.43 V. The GMPP is located at 700.20 W in cluster 1.

During the tracking process under SPSC2, as illustrated in Fig. 12, all algorithms, including IIC, MIC, APO, and PO, except APO-MPC, CMPC, and IC, get trapped in LMPPs, stabilizing at lower power levels, which results in significant energy loss. APO and IC algorithms take the longest to achieve the output power of 594.40 W at 0.58 s and 714.20 W at 0.99 s, respectively. Although PO, IIC, and APO were successfully settled quickly around the LMPP of 591.92 W, they failed to find the optimal GMPP, leading to power losses. The APO-MPC algorithm has smoothly tracked the optimal power point at 0.25 s by extracting the output power of 728.32 W with a power efficiency of 99.43%. It requires the same settling time for both CPSC1 and CPSC2 scenarios. The rise times for PO, APO, IC, MIC, IIC, CMPC, and APO-MPC are 0.05 s, 0.21 s, 0.38 s, 0.05 s, 0.09 s, 0.09 s, and 0.13 s, respectively, while their settling times are 0.06 s, 0.58 s, 0.99 s, 0.13 s, 0.10 s, 0.27 s, and 0.25 s respectively. In terms of tracking speed and efficiency, APO-MPC tracks a maximum power of 728.32 W without any significant oscillations, followed by CMPC at 716.51 W with significant oscillations initially in transient response, IC at 714.20 W without oscillations, IIC at 596.11 W with 16.32 W oscillations, APO at 494.40 W with oscillations during rise time, PO at 573.61 W with 14.46 W oscillations, and MIC at 460.23 W with 40.14 W oscillations. APO-MPC demonstrates the highest tracking speed and efficiency without expressing significant oscillations after settling in the steady state.

Figure 13 shows a power comparison under CPSC. During the tracking process, all algorithms except APO-MPC get trapped in LMPPs, stabilizing at lower power levels, which results in significant energy loss. APO and IC algorithms take the longest to settle into the LMPPs of 474.81 W at 0.68 s and 605.08 W at 0.99 s. Although PO, MIC, IIC, and CMPC were successfully settled quickly, they failed to find the optimal GMPP leading to power losses. The APO-MPC algorithm has smoothly tracked the optimal power point at 0.26 s by extracting the output power of 695.76 W with a power efficiency of 99.36%. Depending on the irradiance complexity, it requires slightly more settling time under CPSCs than SPSCs. The rise times for PO, APO, IC, MIC, IIC, CMPC, and APO-MPC are 0.04 s, 0.24 s, 0.42 s, 0.05 s, 0.09 s, 0.13 s, and 0.12 s, respectively, while their settling times are 0.06 s, 0.58 s, 0.99 s, 0.11 s, 0.10 s, 0.55 s, and 0.26 s. In terms of tracking speed and efficiency, APO-MPC tracks a maximum power of 695.76 W without any oscillations, followed by CMPC at 644.92 W with significant oscillations initially, IIC at 586.40 W with 9.38 W oscillations, PO at 564.07 W with 15.67 W oscillations, IC at 511.70 W, APO at 474.95 W with oscillations during rise time, and MIC at 434.37 W with 36.46 W oscillations. APO-MPC demonstrates the highest tracking speed and efficiency.

This scenario is analyzed to evaluate the adaptability of the MPPT controller under dynamic PSCs. The PV array configuration and DC-DC converter parameters remain the same. Figure 14 presents a power comparison under a rapid transition from pattern 2 to pattern 4 at 0.5 s. During 0.0 s to 0.5 s under pattern 2, the power tracked by APO-MPC is 827.91 W, while CMPC, IIC, APO, MIC, IC, and PO track powers of 817.74 W, 816.77 W, 757.81 W, 760.08 W, 736.60 W, and 700.05 W, respectively. However, APO, IC, and CMPC struggle to achieve stable tracking, resulting in the lowest tracked power. While PO, MIC, IIC, and APO-MPC exhibit the shortest tracking time. During 0.5 s to 1.0 s after the transition from pattern 2 to pattern 3, where the GMPP is 700.20 W. The power values tracked by PO, APO, IC, MIC, IIC, CMPC, and APO-MPC are 444.11 W, 522.90 W, 545.28 W, 505.91 W, 581.83 W, 641.76 W, and 696.64 W, respectively. Under the dynamic transition, the APO-MPC algorithm maintains a tracking efficiency of 99.49%, consistent with its performance in pattern 4 of case 1. However, the tracking efficiencies of CMPC, IIC, and PO decreased by 0.45%, 0.63%, and 17.15%, respectively. The power efficiencies of IC, MIC, and APO increased by 4.42%, 9.49%, and 6.71% respectively. In summary, the APO-MPC demonstrates excellent adaptability to dynamic PSCs, efficiently tracking multiple times in response to changing external irradiance. This robust performance in multistage tracking highlights its capability to handle dynamic shading conditions effectively. Table 5 presents the overall performance of all techniques across UIC, SPSCs, and CPSCs.

The comparison of rise times achieved by all algorithms under various irradiance patterns is presented in Fig. 15. The rise time represents the duration required for tracking the GMPP after an environmental variation, ensuring optimal power generation. For instance, IC has the longest average rise time of 0.34 s to reach the GMPP, followed by APO at 0.20 s and CMPC at 0.16 s. In contrast, APO-MPC, IIC, MIC, and PO exhibit the shortest rise times of 0.13 s, 0.10 s, 0.06 s, and 0.04 s, respectively.

Similarly, the comparison of computational times utilized by all algorithms under various irradiance patterns is presented in Fig. 16. The computational time refers to the amount of time required for processing the necessary computations to track GMPP after an environmental variation. The IC has taken the longest average computational time of 11.72 s to obtain the GMPP, which is followed by CMPC at 7.88 s, IIC at 6.75 s, and APO at 5.08 s. Meanwhile, APO-MPC, MIC, and PO exhibit the shortest rise times of 4.82 s, 4.72 s, and 3.15 s, respectively.

Power oscillations refer to the fluctuations in output power that occur around the optimal point, which can affect the stability and efficiency of power generation. The comparison of SSOs of all algorithms under various irradiance patterns is presented in Fig. 17. The MIC exhibits the highest average power oscillations at 40.44 W, followed by PO at 21.86 W and IIC at 18.71 W. In contrast, CMPC, APO, APO-MPC, and IC show the lowest SSOs of 1.78 W, 0.85 W, 0.71 W, and 0.03 W, respectively.

The tracking efficiency exhibits its ability to optimize the GMPP accurately and efficiently, ensuring maximum power extraction under varying environmental conditions and preventing it from falling into the LMPPs. The comparison of tracking efficiencies of all algorithms under various irradiance patterns is presented in Fig. 18. The APO-MP presents the highest average efficiency at 99.46%, followed by CMPC at 96.53%, IC at 91.00%, IIC at 89.96%. However, APO, MIC, and PO show the lowest efficiencies of 80.99%, 78.32%, and 76.21%, respectively. The APO-MPC algorithm outperforms all other approaches, presenting the shortest rise time, lowest computational time, minimal power oscillations, and the highest tracking efficiency. It effectively tracks the GMPP, ensuring optimal power extraction under diverse weather conditions.

The fast-tracking capability of any MPPT strategy is crucial for optimizing maximum power extraction through a PV system, especially under fluctuating weather conditions. Ensuring that the MPPT controller quickly and accurately tracks the MPP allows the PV system to operate at its optimal level, maximizing output power and enhancing long-term performance. This is achievable only if the algorithm requires minimal computational time for its optimization process. The average computational time and overall efficiency across all irradiance profiles for PO, APO, IC, MIC, IIC, CMPC, and APO-MPC are 3.15, 5.08, 11.72, 4.72, 6.75, 7.88, and 4.82 s, with corresponding efficiencies of 76.21%, 80.99%, 91.00%, 78.32%, 89.96%, 96.53%, and 99.46%, respectively. The APO-MPC algorithm maintains a tracking efficiency of over 99% under all patterns of case 1. Similarly, the CMPC algorithm achieves efficiency above 97% under pattern 1 and pattern 2, but its efficiency drops to just 92.10% under pattern 4, resulting in minimal energy output. IIC and MIC face the same challenge, maintaining above 90% under pattern 1 and pattern 2 but reducing the efficiency to 83.74% and 62.03%, respectively, under pattern 4. These variations highlight the impact of CPSC on the tracking effectiveness of different MPPT technologies, revealing that some technologies struggle to adapt to complex irradiance patterns and can only handle SPSCs. The APO-MPC technology, however, demonstrates strong environmental adaptability in managing CPSC.

Case 2

Case 1

examines uniformly distributed, simple, and complex irradiance profiles. Case 2 incorporates environmental data from Lahore city, Punjab, Pakistan, to evaluate MPPT technology performance under real-time dynamic weather conditions. The environmental data, including irradiance and temperature variations, are sourced from measurement stations operated by the Government of Pakistan and are publicly available in the “World Bank” data repository. Figure 19 illustrates the irradiance levels across the four seasons in Lahore city, with hourly measurements. The PV system used in this case is identical to the one in case 1. In this section, the system’s peak power, average power, and power oscillations are analyzed to assess the MPPT technology’s effectiveness. The APO-MPC method achieves higher output power during the spring, which has the highest solar irradiance levels, allowing for greater power extraction through the PV system. Figure 20 compares output power tracking by different MPPT approaches in the autumn season. Over an 18-hour period, the APO-MPC achieved a peak power of 621.90 W, followed by CMPC with 544.17 W, APO with 501.17, PO with 500.42 W, IIC with 496.02 W, IC with 489.73 W, and MIC with 433.84 W. The corresponding average powers were 217.72 W, 168.12 W, 98.55 W, 93.37 W, 96.94 W, 77.36 W, and 74.81 W, respectively. The APO-MPC, CMPC, and IC have zero SSOs, and the APO-MPC’s peak power tracking was approximately 13% higher than that of other techniques.

Figure 21 compares output power tracking by different MPPT approaches in the spring season. The APO-MPC achieved a peak power of 1427.46 W in the spring, while CMPC obtained 1401.80 W, IIC tracked 1377.41 W, MIC harvested 1209.4 W, IC extracted 1220.24 W, APO achieved 1289.91 W, and PO acquired 1270.23 W. Similarly, the average powers of the corresponding techniques are 768.24 W, 539.89 W, 481.76 W, 350.12 W, 361.29 W, 413.0 W, and 393.20 W, respectively. APO-MPC improved power tracking in the spring by approximately 2% compared to other algorithms.

In summer season, the APO-MPC achieved peak power of 907.02 W, followed by CMPC with 855.63 W, IIC with 783.94, MIC with 606.43 W, IC with 795.53 W, APO with 719.52 W, and PO with 703.18 W as presented in Fig. 22. The corresponding average powers were 477.22 W, 326.24 W, 263.39 W, 241.21 W, 253.45 W, 209.58 W and 206.91 W, respectively. The APO-MPC’s peak power tracking was approximately 6% higher than other techniques. Figure 23 compares output power tracking by different MPPT approaches in the winter season. The APO-MPC achieved a peak power of 1176.68 W, while CMPC obtained 1163.58 W, IIC tracked 1145.21 W, MIC harvested 995.52 W, IC extracted 1091.79 W, APO achieved 1023.19 W, and PO acquired 978.28 W. Similarly, the average powers of the corresponding techniques are 688.42 W, 524.06 W, 472.57 W, 331.23 W, 297.12 W, 269.51 W, and 311.91 W, respectively. The APO-MPC methodology demonstrates adaptability to real-world application environments. APO-MPC’s faster convergence, accurate power tracking, and absence of oscillations at the GMPP help minimize the power losses during the tracking process, resulting in higher power extraction. The comparative analysis of the various MPPT techniques under case 2 is presented in Table 6.

While evaluating the performance of the APO-MPC approach under various irradiance profiles, it is evident that its output curve at the GMPP is smooth and free of oscillations, significantly minimizing power losses as illustrated in Fig. 24. Additionally, it is capable of tracking the optimal point within approximately 0.24 s on average. Compared to other MPPT techniques, convergence and computational times are enhanced. Similarly, the average power it generates increases by 2–13%, reflecting a positive impact of these improvements. Under all weather conditions, it achieves an average tracking efficiency of 99.47%, extracting more power even in complex profiles. Moreover, this technique is compared against other techniques across various factors, as detailed in Table 7.

Experimental validations

This section employs a hardware platform to validate the experimental performance of the APO-MPC algorithm. The hardware setup consists of WSL-C006 OEM solar modules, B25 voltage sensors, Loulensy DC transducers, Arduino UNO R3, PIC16 F877 A microcontroller, IRF630-N MOSFET switch, and 12 V DC motor as a load. The APO algorithm generates an analog signal of reference current using a microcontroller and transmits it to the Arduino. The digital oscilloscope interprets current values and records voltage values to measure output power. A sensor board facilitates the measured values of current and voltage for the PV module to detect the shading effect. The control algorithm uploaded to the Arduino controller optimizes the duty cycle and sends the control input to adjust the switching state of the converter. The technical parameters of the PV modules are detailed in Table 8. At the same time, the experimental setup is illustrated in Fig. 25. The 6 × 1 PV array is configured in a parallel string of 6 series connected modules, operating under irradiance levels of 1000 W/m² and 0 W/m². In round 1, the P-V characteristics are estimated under UIC, SPSC, and CPSC with maximum output powers of 14.99 W, 9.31 W, and 6.19 W, respectively, as presented in Fig. 26.

In round 1, all six PV modules were exposed directly to sunlight at noon to validate UIC. The voltage and current values are recorded as 30.43 V and 481 mA at 0.13 s, respectively, and it achieved an output power of 14.64 W as presented in Fig. 27. To examine SPSC, two modules were shaded using cardboard approximately at 2.09 s, and output power falls drastically towards GMPP. The voltage, current, and power record values are 17.21 V, 525 mA, and 9.04 W, settled at 2.24 s. Similarly, three modules were shaded at 4.02 s, and output parameters were observed to validate CPSC. The voltage and current values are recorded as 19.22 V and 310 mA at 4.17 s, respectively, and it achieved an output power of 5.96 W. The recorded parameters obtained from the hardware setup stay close to the GMPP in all scenarios, and APO-MPC has expressed an overall efficiency of 97.02% in round 1. However, the output values differed slightly from the simulated results, likely due to random shading and actual environmental solar irradiance.

Furthermore, another round of experimental tests is conducted under diverse and realistic conditions to validate the proposed control strategy’s effectiveness. In the case of SPSC1, four modules were exposed directly to sunlight; one module was 40% partially shaded using cardboard that blocks solar irradiance, and one module was entirely covered with it. In SPSC2, three modules were fully exposed; one was entirely shaded with a semi-transparent sheet, and 40% was partially shaded using cardboard and fully covered. Similarly, in CPSC, one module has full irradiance, two modules were 25% and 50% partially shaded, respectively, one module was entirely shaded with a semi-transparent sheet, another module was entirely shaded with two semi-transparent sheets, and one module was fully covered using cardboard. The P-V characteristics are estimated under SPSC1, SPSC2, and CPSC with maximum output powers of 9.30 W, 6.45 W, and 3.63 W, respectively, as presented in Fig. 28. As observed, multiple MPPs are visible on the P–V characteristic curves.

Under SPSC1, the voltage and current values are recorded as 18.23 V and 498 mA at 0.26 s, respectively, and it achieved an output power of 9.08 W with an efficiency of 97.63% as presented in Fig. 29. The recorded rise time is 0.24 s, settling time is observed as 0.39 s, SSOs are measured as 0.32 W.

Under SPSC2, the voltage and current values are recorded as 13.01 V and 484 mA at 0.25 s, respectively. It achieved an output power of 6.30 W with an efficiency of 97.67% as presented in Fig. 30. The observed parameters include a rise time of 0.22 s a settling time of 0.37 s and SSOs of 0.34 W. Similarly, the voltage and current values are recorded as 12.17 V and 285 mA at 0.25 s, respectively, under CPSC, and it achieved an output power of 3.47 W with an efficiency of 95.59%, as presented in Fig. 31.

The recorded rise time is 0.23 s, the settling time is observed as 0.37 s, and SSOs are measured as 0.33 W. In this case of the complex shading effect, the performance efficiency decreased a little; however, other factors, including rise time, settling time, and SSOs, remained almost the same. Table 9 illustrates the comparative quantitative analysis of the proposed strategy conducted for experimental validation regarding rise time, convergence time, settling time, SSOs, tracked power, and overall efficiency. The GMPP power obtained UIC, SPSC1, SPSC2, and CPSC is 14.67 W, 9.08 W, 6.30 W, and 3.47 W, respectively, with corresponding tracking efficiencies of approximately 97.67%, 97.63%, 97.67%, and 95.59%. The SSOs found in all scenarios are merely ignorable as they have approximately 0.33 W, 0.32 W, 0.34 W, and 0.33 W, respectively. Similarly, the comparative analysis of the proposed strategy with existing controllers is illustrated in Table 10. In terms of processor requirements, these can vary depending on the scalability of the PV system, as more complex systems with higher power ratings may require additional processing resources. However, the APO-MPC algorithm has been optimized to perform efficiently on the Arduino UNO while ensuring scalability. Although the recorded parameters obtained from the hardware setup stay close to the GMPP in all scenarios, APO-MPC has expressed an overall average efficiency of 97.14%. However, the output values differed slightly from the simulated results of an overall average efficiency of 99.46%, likely due to inaccurate or delayed irradiance measurements which has affected its ability to track the GMPP effectively. Additionally, the algorithm’s performance under ultra-fast shading transitions could be impacted, as rapid changes in irradiance may not be detected quickly enough by the system. These factors have affected the overall efficiency in a real-time environment. However, future improvements, such as utilizing high-quality sensors could help mitigate these limitations.

The APO-MPC algorithm demonstrates superior performance primarily due to its predictive nature compared to hybrid metaheuristic approaches like PSO-GWO26 which relies on iterative optimization of PID gains. This predictive capability allows it to achieve efficient GMPP tracking without SSOs, resulting in a higher efficiency of 99.46% in simulations and 97.14% experimentally compared to PSO-GWO with a slightly lower efficiency of 95–98%. Similarly, it achieves convergence in just 0.17 s and a settling time of 0.24 s with zero SSOs outperforming PSO-GWO, which tend to exhibit longer settling times and higher SSOs due to their stochastic nature. The comparative analysis indicates that the proposed strategy achieves the highest tracking efficiency, minimum SSOs, and fast convergence response in comparison with other existing techniques. Additionally, it effectively tracks the GMPP, ensuring optimal power extraction under diverse weather conditions.

Conclusion and future work

In this paper, a PV system is developed using the APO-MPC algorithm to address the issues of power loss, SSOs, slow convergence, and low tracking efficiency under dynamic weather profiles. By analyzing different scenarios like UIC, SPSCs, and CPSC, including field atmospheric data from Lahore city, a comparative evaluation was conducted between APO-MPC and other existing MPPT controllers, such as PO, APO, IC, MIC, IIC, and CMPC. The outcomes demonstrate that it excels in GMPP tracking across various weather conditions, achieving an average tracking efficiency of 99.46% under all shading effects. Compared to other techniques, it shows fast convergence within 0.19 s, improved settling time of 0.24 s, reduced SSOs of 0.30 W, and a 2–13% improvement in power generation. On the hardware setup, it achieved an average tracking efficiency of 97.14% at 0.23 s with a more stable output power, exhibiting SSOs around 0.33 W. Based on tests and validations, the proposed approach outperforms all other techniques, presenting the shortest rise time, lowest computational time, minimal power oscillations, and the highest tracking efficiency while effectively tracking the GMPP to ensure optimal power extraction under diverse weather conditions. Thus, the algorithm effectively resolves issues like power oscillations, low tracking efficiency, and falling into LMPPs under SPSCs and CPSC. The improvements in computational time, tracking efficiency, and power extraction indicate that the APO-MPC strategy is highly effective in optimizing energy utilization from PV systems. While this study focuses on a standalone PV system, future research could apply the algorithm to grid-connected systems to further evaluate its practical performance and efficiency. The study aims to explore the integration of the APO-MPC algorithm within grid-connected PV systems to enhance compatibility with smart grid infrastructures. Additionally, it plans to investigate the scalability of the algorithm for larger and more complex PV array configurations, including multi-string and distributed systems. This will involve evaluating its real-time performance and effectiveness for utility-scale PV applications. A promising direction for future research is the integration of MPPT control strategies with VPP frameworks. Such an approach could enhance energy dispatch reliability and further optimize grid-based solar power applications.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are publicly available in the World Bank repository, https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/search/dataset/0038550/Pakistan-Solar-Radiation-Measurement-Data.

Abbreviations

- ANN:

-

Artificial neural network

- APO:

-

Adapted perturb and observe

- APO-MPC:

-

Adapted perturb and observe based model predictive control

- APSO:

-

Adaptive particle swarm optimization

- BESS:

-

Battery energy storage system

- CMPC:

-

Conventional model predictive control

- CPSCs:

-

Complex partial shading conditions

- CVT:

-

Constant voltage technique

- DI:

-

Diffuse irradiance

- DNI:

-

Direct normal irradiance

- ETI:

-

Extraterrestrial irradiance

- FLC:

-

Fuzzy logic control

- GA:

-

Genetic algorithm

- GMPP:

-

Global maximum power point

- GWO:

-

Grey wolf optimization

- IC:

-

Incremental conductance

- IIC:

-

Improved incremental conductance

- ISSA:

-

Improved salp swarm algorithm

- LADRC:

-

Linear active disturbance rejection control

- LMPPs:

-

Local maximum power points

- MIC:

-

Modified incremental conductance

- MMSCC:

-

Modified multi-stepped constant current

- MPPT:

-

Maximum power point technique

- NGWO:

-

Novel grey wolf optimization

- NPID:

-

Nonlinear proportional integral derivative

- OP:

-

Optimal point

- PO:

-

Perturb and observe

- PSC:

-

Partial shading condition

- PSO:

-

Particle swarm optimization

- PV:

-

Photovoltaic

- SMC:

-

Sliding mode control

- SPSCs:

-

Simple partial shading conditions

- SPSOA:

-

Salp particle swarm optimization algorithm

- SSOs:

-

Steady-state oscillations

- SSPSO:

-

Series salp particle swarm optimization

- STC:

-

Standard testing conditions

- UIC:

-

Uniform irradiance condition

- VCM:

-

Voltage control method

- VPP:

-

Virtual power plants

- VSS:

-

Variable step size

References

Etezadinejad, M., Asaei, B., Farhangi, S. & Anvari-Moghaddam, A. An Improved and Fast MPPT Algorithm for PV Systems under Partially Shaded Conditions, IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 732–742, Apr. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1109/TSTE.2021.3130827

Sharma, H. et al. Feasibility of solar Grid-Based industrial virtual power plant for optimal energy scheduling: A case of. Indian Power Sect. Energies. 15 https://doi.org/10.3390/en15030752 (2022).

Lodhi, M. K. et al. Harnessing rooftop solar photovoltaic potential in Islamabad, Pakistan: A remote sensing and deep learning approach. Energy 304, pp. 132256, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENERGY.2024.132256 (Sep. 2024).

Mirza, F., Ling, Q., Javed, M. Y. & Mansoor, M. Novel MPPT techniques for photovoltaic systems under uniform irradiance and partial shading. Sol. Energy. 184 (7), 628–648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2019.04.034 (2019).

Gil-Velasco & Aguilar-Castillo, C. A modification of the perturb and observe method to improve the energy harvesting of PV systems under partial shading conditions. Energies 14,. https://doi.org/10.3390/EN14092521 (2021). 9, pp. 2521, Apr.

Siddique, M. A. B., Zhao, D. & Jamil, H. Forecasting optimal power point of photovoltaic system using reference current based model predictive control strategy under varying climate conditions. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 22 (10), 3117–3132. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12555-023-0823-7 (Oct. 2024).

Siddique, M. A. B. et al. Implementation of incremental conductance MPPT algorithm with integral regulator by using boost converter in Grid-Connected PV array. IETE J. Res. 69 (6), 3822–3835. https://doi.org/10.1080/03772063.2021.1920481 (2023).

Asnil, R., Nazir, K., Krismadinata & Sonni, M. N. Performance Analysis of an Incremental Conductance MPPT Algorithm for Photovoltaic Systems Under Rapid Irradiance Changes, TEM Journal, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 1087–1094, May (2024). https://doi.org/10.18421/TEM132-23

Shahin, H. H. et al. Maximum power point tracking using cross-correlation algorithm for PV system. Sustainable Energy Grids Networks. 34, 101057. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SEGAN.2023.101057 (Jun. 2023).

Lasheen, M., Rahman, A. K. A., Abdel-Salam, M. & Ookawara, S. Performance enhancement of constant voltage based MPPT for photovoltaic applications using genetic algorithm. Energy Procedia. 100, 217–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EGYPRO.2016.10.168 (Nov. 2016).

Cavalcanti, M. C. et al. Hybrid maximum power point tracking technique for PV modules based on a Double-Diode model. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 68 (9), 8169–8181. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2020.3009592 (Sep. 2021).

Kumar, M. et al. Comprehensive review of conventional and emerging maximum power point tracking algorithms for uniformly and partially shaded solar photovoltaic systems. IEEE Access. 11, 31778–31812. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3262502 (2023).

Ahmed, M. et al. An improved photovoltaic maximum power point tracking technique-based model predictive control for fast atmospheric conditions. Alexandria Eng. J. 63, 613–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AEJ.2022.11.040 (Jan. 2023).

Manna, S., Akella, A. K. & Singh, D. K. Novel Lyapunov-based rapid and ripple-free MPPT using a robust model reference adaptive controller for solar PV system. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 8 (1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1186/S41601-023-00288-9 (Dec. 2023).

Asif, R. M. et al. Design and analysis of robust fuzzy logic maximum power point tracking based isolated photovoltaic energy system. Eng. Rep. 2 (9), e12234. https://doi.org/10.1002/eng2.12234 (2020).

da Lopes, C. et al. An enhanced voltage control method for fair active power curtailment of rooftop PV systems in LV distribution networks. Sustainable Energy Grids Networks. 39, 101409. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SEGAN.2024.101409 (Sep. 2024).

Allahabadi, S., Iman-Eini, H. & Farhangi, S. Fast artificial neural network based method for Estimation of the global maximum power point in photovoltaic systems. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 69 (6), 5879–5888. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2021.3094463 (Jun. 2022).

Ouatman, H. & Boutammachte, N. E. A genetic algorithm approach for flexible power point tracking in partial shading conditions. Results Eng. 24, 102940. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RINENG.2024.102940 (Dec. 2024).

Azeem, F. et al. Load management and optimal sizing of Special-Purpose microgrids using two stage PSO-Fuzzy based hybrid approach. Energies 15 https://doi.org/10.3390/en15176465 (2022).

Jayaudhaya, J., Ramash Kumar, K., Tamil Selvi, V. & Padmavathi, N. Improved Performance Analysis of PV Array Model Using Flower Pollination Algorithm and Gray Wolf Optimization Algorithm, Mathematical Problems in Engineering, vol. Aug. 2022, (2022). https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5803771

Hadj Salah, Z. B. et al. Jun., A New Efficient Cuckoo Search MPPT Algorithm Based on a Super-Twisting Sliding Mode Controller for Partially Shaded Standalone Photovoltaic System, Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 12, p. 9753, (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129753

Siddique, M. A. B. et al. An adapted model predictive control MPPT for validation of optimum GMPP tracking under partial shading conditions. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-59304-z (Apr. 2024).

Matius, M. E. et al. On the optimal Tilt angle and orientation of an On-Site solar photovoltaic energy generation system for Sabah’s rural electrification. Sustainability 13 (10), 5730. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU13105730 (May 2021).

Celikel, R., Yilmaz, M. & Gundogdu, A. Improved voltage scanning algorithm based MPPT algorithm for PV systems under partial shading conduction. Heliyon 10 (20), e. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HELIYON.2024.E39382 (Oct. 2024).

Ibrahim, W. et al. Intelligent adaptive PSO and linear active disturbance rejection control: A novel reinitialization strategy for partially shaded photovoltaic-powered battery charging. Comput. Electr. Eng. 123, Part A,, 110037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2024.110037 (2025).

Águila-León, J., Vargas-Salgado, C., Díaz-Bello, D. & Montagud-Montalvá, C. Optimizing photovoltaic systems: A meta-optimization approach with GWO-Enhanced PSO algorithm for improving MPPT controllers. Renew. Energy. 230, pp. 120892, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RENENE.2024.120892 (Sep. 2024).

Dagal, A. W., Ibrahim, A. & Harrison Leveraging a novel grey Wolf algorithm for optimization of photovoltaic-battery energy storage system under partial shading conditions. Comput. Electr. Eng. 122, 109991. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2024.109991 (2025).

Ibrahim, W. et al. A high-speed MPPT based horse herd optimization algorithm with dynamic linear active disturbance rejection control for PV battery charging system. Sci. Rep. 15, 3229. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85481-6 (2025).

Ibrahim, W. et al. Intelligent nonlinear PID-Controller combined with optimization algorithm for effective global maximum power point tracking of PV systems. IEEE Access. 12, 185265–185290. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3513355 (2024).

Dagal, B., Akın & Akboy, E. MPPT mechanism based on novel hybrid particle swarm optimization and salp swarm optimization algorithm for battery charging through simulink. Sci. Rep. 12, 2664, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-06609-6 (2022).

Padmavathi, N., Chilambuchelvan, A. & Shanker, N. R. Maximum power point tracking during partial shading effect in PV system using machine learning regression controller. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 16 (2), 737–748. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42835-020-00621-4 (Mar. 2021).

Dagal, B., Akın & Dari, Y. D. A modified multi-stepped constant current based on Gray Wolf algorithm for photovoltaics applications. Electr. Eng. 106, 3853–3867. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00202-023-02180-z (2024).

Dagal, B., Akın & Akboy, E. A novel hybrid series salp particle swarm optimization (SSPSO) for standalone battery charging applications. Ain Shams Eng. J. 13 (5), 101747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2022.101747 (2022).

Dagal, B., Akin & Akboy, E. Improved salp swarm algorithm based on particle swarm optimization for maximum power point tracking of optimal photovoltaic systems. Int. J. Energy Res. https://doi.org/10.1002/er.7753 (2022).

Zhao, L. & Yin, L. Multi-step depth model predictive control for photovoltaic maximum power point tracking under partial shading conditions. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 151 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijepes.2023.109196 (Sep 2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Muhammad Abu Bakar Siddique: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Validation, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft. Dongya Zhao: Supervision, Investigation, Writing– review & editing. Khmaies Oua-hada: Data curation, Resources, Formal Analysis, Writing– review & editing. Ateeq Ur Rehman: Validation, Investiga-tion, Writing– review & editing. Habib Hamam: Formal Analysis, Data curation, Writing– review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Siddique, M.A.B., Zhao, D., Ouahada, K. et al. Performance validation of global MPPT for efficient power extraction through PV system under complex partial shading effects. Sci Rep 15, 17061 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01816-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01816-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Comparative analysis of maximum power point tracking methods for power optimization in grid tied photovoltaic solar systems

Discover Applied Sciences (2025)