Abstract

Rapid identification of groundwater sources is crucial for emergency water supplies. Yudu County (YDC) in Southern China serves as a case study due to its typical mountainous terrain and pressing groundwater demands. To address the limitations of conventional groundwater mapping methods in large-scale areas with sparse data, this study integrates remote sensing (RS), geographic information systems (GIS), and multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) techniques to delineate groundwater potential zones (GWPZs) in YDC. Following a series of correlation tests, seven assessment indicators were selected from various groundwater influencing factors, including two innovative ones: terrestrial water storage change (TWSC) and spring flow. The analytic hierarchy process (AHP) and fuzzy AHP (FAHP) models were employed to calculate factor weights, and GWPZ maps were generated using weighted overlay analysis in GIS. The model performance was validated using borewell data, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, and yield prediction models. Additionally, four water enrichment types and their spatial distribution were identified by field investigations and yield prediction assessments. Results indicated a remarkable similarity between GWPZs delineated by AHP and FAHP, categorized into five classes: very high (13.92% for AHP and 14.33% for FAHP), high (26.29 and 27.55%), medium (29.33 and 28.14%), low (20.66 and 21.50%), and very low (9.80 and 8.48%). The area under the curve (AUC) for FAHP was 85.09%, slightly higher than the 84.41% of AHP, while the correlation coefficient (R2 of the prediction model improved from 0.747 to 0.817 with FAHP. These findings confirmed the reliability of combining GIS and MCDA methods to delineate GWPZs, with FAHP demonstrating an advantage over AHP. The proposed methodology and resulting mapping significantly enhance sustainable water resource management and development in YDC, offering a practical framework for rapid groundwater investigations in disaster response, as well as for long-term water security planning in similar mountainous environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Groundwater is a critical water source in mountainous areas, particularly during droughts when surface water is insufficient, and its quality may be unreliable1. It plays a pivotal role in maintaining regional stability, ecological balance, and sustaining life activities2,3. China, recognized as one of the world’s predominant mountainous nations, has approximately 6.22 million square kilometers of mountainous terrain, covering about 64.9% of its total land area4. The southern hilly mountain region stands out as the largest hilly area in China, functioning as a vital ecological barrier that supports water conservation, soil preservation, and the maintenance of biodiversity. However, this region is experiencing a rising demand for water resources, driven by population growth, industrial expansion, and extreme climate variations5. In particular, Yudu County (YDC) exemplifies the unique attributes and socio-economic prospects of the southern mountainous region, serving as a historical revolutionary base6. Unfortunately, inadequate water security has negatively impacted its sustainable development in recent years due to the complex terrain and recurrent seasonal droughts. For example, during 2019 and 2022, consecutive extreme droughts affected over 100,000 people in this area, deprived tens of thousands of acres of agricultural hectares of farmland of irrigation water, and caused economic losses amounting to hundreds of millions of dollars7. The increasing frequency and intensity of droughts, driven by abrupt regional climate changes, have highlighted the urgent need for sustainable and high-quality groundwater resources. In 2021, YDC received timely support from the National Project “Targeted Poverty Alleviation” to explore emergency groundwater8. Consequently, identifying the potential distribution of groundwater in YDC has become an immediate priority for local authorities. Our focus also extends to the investigation of groundwater potential zones (GWPZs) within this region, aimed at quickly locating optimal areas for groundwater development and ensuring a reliable emergency water supply, particularly in response to disasters.

The rugged terrain, high altitude, and dense forests present significant challenges for groundwater exploration in mountainous areas9. Consequently, various methods have been proposed for application, including topography, geological/hydrogeological investigation, drilling, and geophysical and geochemical techniques, as illustrated in (Fig. 1). In the early 20th century, researchers mainly used topography to identify groundwater. Notably, Chatterji & Singh10 proposed a hydrogeomorphic technique to expedite the exploration of groundwater areas in the Indian arid zone. Sreedevi et al.11 revealed the significance of morphometric analysis for obtaining GWPZs in a structurally controlled terrain. The advent of electrical resistivity profiling in 1912 advanced various geophysical methods for groundwater investigation, including magnetic surveys, resistivity measurements, and shallow-refracted seismic methods12. Recent studies by Lubang et al.8, Gomo13, and Zheng et al.14 have effectively mapped groundwater distribution across different aquifers by integrating these approaches with hydrogeological analyses. Drilling provides well tests and validates findings. Furthermore, geochemical methods have evolved since the 1930s from basic chemical analysis to advanced isotope techniques that can clarify the relationship between groundwater and surface water15. Welch & Allen16 and Segura et al.17 evaluated groundwater runoff properties in mountain regions using geochemical processes that reveal the control of stratigraphic structures, recharge mechanisms, and topographic features on groundwater.

Despite the guidance provided by studying groundwater recharge, reservoir structure, or runoff patterns, these conventional methods rely on on-site input from experts and suffer from limitations, including narrow focus, limited detection range, high cost, and time consumption, making them impractical for large-scale emergency groundwater sourcing in complex terrains. Thus, the consideration of modern data preparation and integration methods and innovative decision-making processes for detecting groundwater potential has become an urgent need, such as remote sensing (RS), geographic information systems (GIS), and multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA). Since the late 20th century, the rapid development of RS and GIS has offered an economical and efficient alternative for groundwater mapping. RS, which gained prominence in the 1990s with the launch of satellites like Landsat, enables repeated temporal, spatial, and spectral observations, facilitating rapid data acquisition even in inaccessible areas18. Similarly, GIS, which was widely utilized in the early 2000s, integrates data from various sources, including satellite imagery, maps, and field surveys, into a unified framework for acquiring, storing, analyzing, modelling, and sharing geographic data19. Pioneering work by Goodchild (1992) and others established GIS as a critical tool for spatial analysis in hydrology20. Over the past two decades, the application of the MCDA method has also proliferated, proving effective for assessing groundwater potential. It aids in decision-making by weighing multiple objectives and criteria21. Recent studies, such as Golkarian et al.22, Morgan et al.23, and Sadeghi et al.24, have combined MCDA methods (e.g., random forests, neural network, support vector machines) with GIS and RS data, further enhancing the precision and scalability of groundwater mapping techniques.

It is worth mentioning that among the MCDA methods for delineating GWPZs, the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and Fuzzy AHP (FAHP) are the most widely used. These techniques leverage the expert experience and existing data to reveal groundwater occurrence, emphasizing operational simplicity and model transferability25. Their integration with GIS has been successfully applied in various regions, including tropical river basins3,26, semi-arid regions19,27, bedrock aquifers28, and karst water-bearing zones29. However, the comparative studies using both methods with a consistent language scale for importance are limited, particularly in the mountainous areas of southern China, where method applicability needs further validation. Additionally, the formation and storage of groundwater depend on various environmental factors, resulting in the establishment of over 30 assessment indicators for groundwater potential. Researchers typically select many indicators for their studies without considering their homogeneity. For instance, Arabameri et al.30 utilized 15 variables such as slope, rainfall, fault density, and lithology. Similarly, Ikirri et al.31 used 14 factors, while Mallick et al.32 chose 12 elements to map GWPZs. However, according to Suryawanshi et al.33, an excessive number of criteria can lead individuals to lose the thread, resulting in unreliable evaluations. They suggested limiting the number of criteria to a maximum of 9. Furthermore, relying on highly correlated indicators may generate significant errors by magnifying their specific effects. In response to these challenges, the current research employs factor analysis methods to select and optimize evaluation indicators. Consequently, seven indicators have been constructed and utilized, including two innovative metrics. Terrestrial water storage change (TWSC) serves as a substitute for rainfall and offers advantages in effectively distinguishing regional water resource recharge and storage. Furthermore, as the necessary step for the mountainous groundwater survey, the spring flow and distribution investigation has been distilled into a spring flow indicator to assess groundwater potential.

This study integrates RS, GIS, and two MCDA techniques, namely AHP and FAHP, to delineate GWPZs in YDC. Given the limited research on groundwater potential assessments in mountainous regions like YDC, this work addresses critical gaps by refining criteria selection and evaluating the applicability of MCDA models, thereby enhancing the generalizability of findings on water-rich patterns. To achieve this, three key objectives have been prioritized: (1) conducting independence and sensitivity analyses to optimize indicator selection, ensuring their reliability for the typical mountainous terrain; (2) evaluating the model accuracy using data from drilled wells, with validation performed through Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves and statistical indicators; (3) identifying the mountainous groundwater-rich zones along with their distribution patterns based on GWPZ maps. This study proposes a pragmatic framework for the expedited assessment of groundwater potential in YDC and similar mountainous regions, offering significant insights into the sustainable development of groundwater resources and the facilitation of emergency exploration initiatives.

Data

The study area

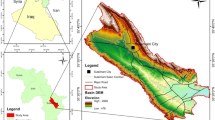

The YDC is situated in southern Jiangxi Province, China, covering approximately 2893 km2, as shown in (Fig. 2). The region has rolling hills with elevations from a few hundred meters to over 1000 m. It is dominated by medium and small hills, interspersed with long and narrow basins. Extensive reddish clastic rock layers and diverse geomorphological features, including Danxia landforms, karsts, and granites, characterize the area. This topographically complex region represents a typical example of the hilly and mountainous terrains of southern China34. The region has a subtropical monsoon climate with abundant rainfall and moderate temperatures, averaging 19.7 °C annually and 1507 mm of precipitation. Its mountainous terrain fosters dense river networks, including the major rivers like Gongshui and Mei rivers. The area is crucial for soil and water conservation and agricultural production but has recently faced frequent and severe droughts, causing critical water shortages.

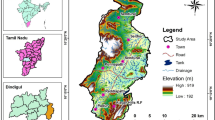

Geologically, the regional strata encompass a wide range of intervals, except for the Ordovician, Silurian, and Tertiary. The structure is complex, prominently featuring fractures and folds. As shown in Fig. 3, these conditions result in diverse groundwater types, including clastic fracture water in the central basins, karst water in limited areas, loose rock pore water near rivers, and bedrock fissure water at the extensive periphery. The unique climatic and hydrological conditions of the region make groundwater a critical resource, particularly during droughts when surface water is scarce. Borehole records reveal significant variability in groundwater yield and quality across the area8. Thus, assessing the region’s groundwater potential and identifying high-potential areas for water extraction are essential for optimizing well sites and reliable emergency water supplies.

Location of the study area: (a) China region, (b) Jiangxi province, (c) Yudu county using ArcMap 10.6.1 software35.

Groundwater types in the study area using ArcMap 10.6.1 software35.

Data preparation

The quantity and spatial distribution of groundwater in a region depend on multiple factors related to groundwater endowment and movement. To comprehensively assess the GWPZs in YDC, various publicly available datasets, including geological maps, hydrogeological maps, satellite images, and field surveys, were utilized. Table 1 details the data types, sources, and accuracies.

Geological data were obtained from the 1:50,000 digital geological map of Yudu County, provided by the Wuhan Center of China Geological Survey (WCCGS). This map features detailed lithology and fault vector data based on revisions and supplementary measurements from the 1:200,000 digital geological map of China, with subdivided maps available through the public GeoCloud website6. Hydrological data were sourced from China’s 1:200,000 regional hydrogeological maps, which form a comprehensive national database containing extensive information on spring distribution and water yield. The validity of these data has been corroborated by Zhang et al.36 in groundwater potential assessment in southwestern China.

Rainfall data were derived from GPM 3IMERGM V07, a satellite precipitation product developed by NASA. This provides global monthly precipitation data at a 0.1°×0.1° resolution. According to Tang et al.37, it demonstrates higher accuracy in China than other satellite and reanalysis products. Monthly evaporation and runoff data were extracted using the NOAH 2.1 model from the global land data assimilation system (GLDAS), which integrates ground- and satellite-based observation data at a resolution of 0.25°×0.25°. Research by Hasan et al.38 has indicated that GLDAS serves as a crucial data source for studying global groundwater changes and hydrological applications. The Digital Elevation Model (DEM) data, with a spatial resolution of 30 m, were sourced from the ASTER GDEM V2 dataset, which has been previously used in GWPZ delineation by Luo et al.39 and Madani & Niyazi40.

Land use data were obtained from the GlobeLand30 V2020 dataset, which offers detailed information on ten land cover types, including cultivated land, grasslands, and artificial surfaces. According to Chen et al.41, this data can capture human activity and landscape patterns, achieving an average accuracy of 80% for both full and individual classes through sample-based validation. Vegetation cover within the study area was represented by the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), derived from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) product MOD13Q1 V6.1, which provides global NDVI data every 16 days at a 250 m resolution. Jin et al.42 have used this data to study vegetation dynamics related to groundwater. The accuracy of the GWPZ assessment was validated using in situ borewell data from WCCGS, containing accurate geographic location and water inflow.

The selection of these reliable datasets was made based on their availability, frequency of use, and adherence to stringent quality control standards established by the producers. The accuracy of these datasets has been validated through their application in relevant groundwater research. Additionally, recommended tools and codes for data extraction were employed to minimize errors attributable to variations in formats, scales, and coordinate systems. Data processing was executed using a suite of GIS spatial analysis tools to ensure data consistency, encompassing tasks such as resampling, resizing, interpolation, tabulation, conversion, raster calculations, and reclassification. Consequently, a standardized GWPZ assessment database has been established within the GIS system.

Methods

The proposed framework

In this study, we integrated RS, GIS, and MCDA techniques to propose a framework for rapid groundwater assessment. Based on the multi-source data collected in YDC, twelve evaluation indicators commonly found in previous literature were established. After correlation and multicollinearity tests, seven key groundwater influencing factors were ultimately selected and digitized into thematic layers. Their respective weights were determined through two multi-criteria decision-making models: AHP and FAHP. The GWPZ categories were then derived by reclassification using GIS-based overlay analysis and calculation of the groundwater potential index (GWPI). Finally, the accuracy of the proposed GWPZ detection method was validated through analyses of model prediction performance and indicator sensitivity. Figure 4 illustrates the technical workflow employed in the study.

Indicator construction

Proper selection of these factors is essential for multi-criteria analysis and identification of GWPZs32. To ensure this objective process, a set of methodological considerations was utilized, including a thorough literature review, geographical characteristics of YDC, and its associated database. Consequently, we chose and constructed twelve indicators to map GWPZs, categorized into four primary groups: (1) topographic factors (slope, relative relief, topographic wetness index (TWI)); (2) geological factors (lithology, distance to faults, fault density, spring flow); (3) hydrological factors (drainage density, distance to rivers, TWSC); and (4) land cover factors (land use, NDVI). The application of these indicators for GWPZ assessment has been documented by various researchers in recent years, as exemplified in (Table 2). It is essential to emphasize that the chosen factors are informed by their prevalent usage and applicability in mountainous environments. Conversely, certain less common criteria, such as soil permeability, water level fluctuation, and runoff coefficient, were excluded due to their controversial effects or difficulties in data availability, despite having demonstrated efficacy in alternative contexts. Furthermore, as preliminary criteria, these identified indicators will necessitate factor analysis to validate correlations prior to their application.

The topography significantly affects groundwater recharge and movement. Slope, the most frequently used topographic indicator, indicates the steepness of the surface50. The slope layer was derived from DEM data using ArcGIS v10.6 software through the terrain analysis function. Geomorphology is another important indicator. Due to the lack of data sources, this study employed a quantitative metric that describes landform morphology, specifically relative relief. It is defined as the maximum elevation difference per unit area and was obtained using DEM data and the Neighborhood Analyst tools in ArcGIS57. Additionally, TWI has been extensively used to describe the effect of topography on the location and size of saturated source areas of runoff generation51. The TWI layer was calculated using SAGA-GIS software and is defined by the following formula:

where \(\:\alpha\:\) is the cumulative upslope area draining through a point and \(\:\beta\:\) is the slope angle at the point.

Lithology controls the porosity, permeability, and karstification of aquifers in bedrock mountainous regions56. Data was extracted from the digital geological map and integrated with lithologic characters to create a lithology layer. Moreover, groundwater enrichment increases as proximity to fractures decreases. A fracture distance layer was generated using fault line data and the Euclidean distance function in ArcGIS v10.6 software. Fault density (\(\:{D}_{f}\)) was calculated using formula (2), with the layer established based on the Line Density tool in ArcGIS. As natural groundwater outcrops, springs provide the most intuitive reflection of groundwater abundance through their spatial distribution and flow rates29. This makes them essential for investigating water sources. In this study, the spring flow layer was constructed by kriging interpolation in ArcGIS v10.6 software.

where \(\:{L}_{f}\) is the total length of faults and \(\:{A}_{f}\) is the coverage area.

In mountainous areas, there is also a vigorous exchange of groundwater with surface water, and aquifers near streams generally have better groundwater storage and recharge. River network data were extracted using DEM data, based on the hydrological analysis tools integrated with ArcGIS software. Drainage density (\(\:{D}_{d}\)) reflects the surface characteristics of the underlying geology of an area54, defined as the length of the channel per unit area according to formula (3). Its layer was similarly derived using the Line Density tool. Moreover, the distance to rivers was also investigated by using the Euclidean distance tool.

where \(\:{L}_{d}\) is the length of the channels and\(\:\:{A}_{d}\) is the unit area.

Rainfall, a key component of the hydrological cycle, is the primary source of surface water and recharge for mountain aquifers through infiltration. Mountainous terrain, influenced by land cover such as woodland and grassland, typically has high evapotranspiration, reducing adequate rainfall recharge. To account for these comprehensive effects, this study replaces traditional rainfall indicators with TWSC, reflecting the water resource variation over a specified period58. The increase signifies effective replenishment and storage, whereas a decrease suggests consumption or loss of water resources in the area. The calculation is based on the watershed water balance equation, given by the following formula:

where \(\:Pre\) is precipitation; \(\:Qs\) is runoff; and \(\:Evap\) is evapotranspiration. These values are calculated by the original monthly data from January 2019 to December 2023 and computing the annual averages. For ease of calculation, all values are converted to millimeters (mm).

Land use was chosen due to its significant impact on groundwater recharge rates, flow patterns, and quality6. Different land use types determine surface infiltration rates and runoff characteristics. Land use data for the study area were extracted from the GlobeLand30 dataset, and thematic layers were constructed in ArcGIS software. Additionally, the coverage of surface vegetation can accurately reflect the accumulation of groundwater48. This study employed the MODIS reprojection tool for data projection and mosaicking, followed by the application of the maximum synthesis method to extract the annual NDVI thematic layer for the year 2023.

Weighting methods

The integration of RS, GIS, and decision-making models has been widely used in hydrological and hydrogeological management. By overlaying multiple thematic layers, MCDA has also proven an effective tool for groundwater exploration, with a key step that assigns appropriate weights to each thematic layer27. Consequently, various MCDA methods have been proposed for delineating GWPZs, including frequency ratios, weights of evidence, random forests, neural networks, and support vector machines. These methods are generally categorized as machine learning and expert decision systems. Machine learning methods exhibit low error rates and perceptual biases but depend heavily on the quantity and quality of training samples22. Additionally, these models have a less transparent decision-making process, making it harder to extract their rules. In contrast, expert decision systems, such as AHP and FAHP, employed in this study typically perform well in data-scarce areas59.

AHP model

Proposed by Thomas L. Saaty in the 1970s, AHP is a multi-criteria decision-making process that integrates subjective judgment into quantitative analysis, featuring simplicity, practicality, and operability25. The process in detecting GWPZs using the AHP model involves four main steps:

Step1: Establishment of the hierarchical structure.

Define the target and criterion layers for decision-making. The target layer is GWPZ detection, while the criterion layer consists of the seven selected groundwater impact factors.

Step 2: Construction of the pairwise judgment matrix.

Based on empirical expert judgments, pairwise comparisons of evaluation factors are made, resulting in a pairwise comparison matrix A containing n factors, as presented in formula (5). In this study, a relative importance scale of 1–9 is used, with reference to the Saaty’s scale in (Table 4). This pairwise comparison simplifies decision-making by allowing the decision-maker to independently assess the impact of each parameter on the overall objective.

where aij represents the relative importance of criterion i with respect to parameter j. Specifically, when i = j, then aij = 1, and aji = 1/aij.

Step 3: Determination of indicator weights.

The normalized weight \(\:{w}_{i}\) of each indicator is calculated using the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the judgment matrix, as follows:

Step 4: Consistency check.

To mitigate bias and inconsistency in subjective evaluation, AHP employs a consistency ratio (CR) to validate the reliability of standardized weights. The results are only considered acceptable if CR\(\:\le\:\:\)0.1. If CR > 0.1, the pairwise comparison matrix must be revised. The CR is computed as:

where CR represents the consistency ratio, RI represents the random consistency index with reference to the Saaty criterion shown in (Table 3), and CI represents the consistency index determined according to formulas (8) and (9).

where \(\:{\lambda\:}_{\text{max}}\) is the maximum eigenvalue of the judgement matrix and W is the weight vector, \((w_{1} ,w_{2} ,...,w_{n} )^{{\text{T}}}\).

FAHP model

One of the many current limitations of AHP is its use of exact numerical values for pairwise comparisons, which may overlook the ambiguity inherent in subjective judgments of the decision maker and the ambiguity in the indicator attributes60. To address this drawback, the FAHP was introduced in 1983, integrating fuzzy set theory with AHP61.

The key difference between AHP and FAHP is that FAHP uses fuzzy numbers to assess the relative importance of elements, rather than exact numbers. For example, the numbers 1/2, 1, 3/2, 2, 5/2, 3, 7/2, 4, 9/2, and 5 are used as fuzzy ratios with interval numbers to indicate the strength of preference27,50. The fuzzy scale can also be adjusted based on the designer’s knowledge level. In the FAHP model, the pairwise comparison scale in the judgement matrix is usually represented by a triangular fuzzy number \(\:\stackrel{\sim}{b}\), whose affiliation function \(\:{\mu\:}_{x}:R\to\:\left(\text{0,1}\right)\), is determined by an array of ternary real numbers at \(\:l\le\:m\le\:u\) in the form:

where l, m, and u represent the lower, middle, and upper values of the fuzzy number respectively.

A triangular fuzzy number can be represented by \(\:(l,m,u)\). when l = m = u, \(\:(l,m,u)\) usually denotes a non-fuzzy number. In addition, the arithmetic of two triangular fuzzy numbers\(\:{M}_{1}=({l}_{1},{m}_{1},{u}_{1})\), \(\:{M}_{2}=({l}_{2},{m}_{2},{u}_{2})\) is defined as follows:

To compare the process of calculating the weights of the indicators in the AHP model, the same semantic ratings of importance as in the Saaty scale were used. FAHP uses the corresponding triangular fuzzy numbers to characterize the degree of priority among the hierarchical criteria, as shown in (Table 4). The weight coefficients of the assessment indicators are then calculated using the geometric mean method proposed by Buckley62. The FAHP process for determining indicator weights involves the following steps:

Step1: Construct the fuzzy pairwise comparison \(\:\stackrel{\sim}{\varvec{A}}\:\)by linguistic variables. The element \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{a}}_{ij}\) consists of triangular fuzzy numbers as in formula (15).

where the matrix element\(\:\:{\stackrel{\sim}{a}}_{ij}\) is taken from the fuzzy triangular scale in (Table 4). When i = j, \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{a}}_{ij}=\stackrel{\sim}{1}=(\text{1,1},1)\), and \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{a}}_{ij}={{\stackrel{\sim}{a}}_{ji}}^{-1}\).

Step 2: Calculate the fuzzy geometric mean \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{r}}_{i}\) and fuzzy weight \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{w}}_{i}\) for each criterion, respectively, according to the following formulas:

where \(\:\oplus\) and \(\:\otimes\) involve fuzzy multiplication and fuzzy addition, respectively. \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{a}}_{in}\) is the fuzzy scale of a given criterion i with respect to indicator n.

Step 3: Defuzzify weights. The fuzzy weights \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{w}}_{i}\) for each indicator are transformed into exact numerical weights \(\:{w}_{i}\) using the region centering method, calculated as follows:

Step 4: Normalize weight vectors. The normalized weight vector \(\:\stackrel{\sim}{\varvec{W}}\) of the evaluation indicators is as follows:

where \(\:{w}_{i}\) is the defuzzified weight of each indicator, \(\:i=\text{1,2},\cdots,n\).

Calculating GWPI

GWPZs were mapped by overlay of all thematic layers using the weighted overlay function of ArcGIS v10.6 software. Factor weight values determined by AHP or FAHP were assigned to each thematic layer, and subclassification and ranking of each layer was performed with expert advice. A pixel-by-pixel, linear weighted combination was used to calculate the GWPI for the study area. The GWPI is a dimensionless quantity that helps to retrieve the possible GWPZs28. Based on the range and distribution of GWPI, the GWPZ map can be generated using a suitable classification scheme in the GIS environment. The specific formula for the calculation of GWPI is given below:

where \(\:{w}_{i}\) and \(\:{r}_{i}\) denote the indicator weights and corresponding subcategory ratings of each thematic layer, respectively. n denotes the number of evaluation factors ultimately selected, SL denotes slope, TWSC denotes terrestrial water storage change, DD denotes drainage density, DF denotes distance to faults, LI denotes lithology, SF denotes spring flow, and LU denotes land use.

Criterion analysis

Multicollinearity analysis

Evaluation models rely on a set of evaluation indicators. When the factors used for GWPZs are highly correlated, their effects can overlap and magnify one another, leading to inaccurate results30. To solve this, Pearson correlation analysis was performed to ensure the independence of assessment factors. Additionally, multicollinearity analysis was used to detect the correlation between the input parameters and other parameter combinations. Its common evaluation indexes were Tolerance (Tol) and Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), calculated as follows:

where R2 is the coefficient of determination of the regression equation.

The coefficient R² reflects the degree to which the regression model fits the data, with higher values indicating a better fit. A smaller Tol value indicates strong multicollinearity between the variables. VIF indicates the degree of influence of multicollinearity on the variance of the regression coefficients. Usually, when the VIF ≥ 10 and Tol < 0.10, it is determined that there is a problem of covariance among the assessed factors63. In this case, it is necessary to consider the elimination of the relevant factors.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis evaluates the influence of input criteria on model outputs and verifies the adaptability of parameters32. This study conducted single-parameter sensitivity analysis on the GWPZ evaluation factors to determine their actual impact on GWPZ. The effective weight \(\:{\stackrel{-}{w}}_{i}\) for each factor was calculated as:

where \(\:{w}_{i}\) is the normalized empirical weight of each factor, \(\:{r}_{i}\) is the subclass rating assigned to the current factor layer, and GWPI is the Groundwater Potential Index calculated by formula (20).

Model validation and evaluation index

The construction of high-quality models in scientific research relies on rigorous validation techniques. In this research, ROC curves were used and water production prediction models were constructed in conjunction with the location of drilled wells and their water volumes to provide a comprehensive assessment of the two MCDA methods.

The ROC curve measures model accuracy by describing the ability of a predefined event to occur correctly or not22. The x-axis of the curve reflects 1-specificity (i.e., the false positive rate, FPR, of the model predictions) and the y-axis represents the sensitivity (i.e., the true positive rate, TPR, of the model predictions). Essentially, the ROC curve is the TPR-FPR curve calculated and plotted at different thresholds. A curve closer to the upper-left corner indicates better model performance, i.e., it indicates that a higher TPR is obtained at a lower FPR. In addition, the area under the curve (AUC) is a key indicator of the overall performance of the model. Its value ranges from 0.5 to 1, with larger values indicating better model differentiation ability. When AUC = 0.5, the model performance is equivalent to random guessing.

In order to test the prediction accuracy of the model, several frequently used statistical metrics were used, including mean square error (MSE), mean absolute error (MAE), mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), root mean square error (RMSE) and coefficient of determination (R2. Lower error values indicate higher model accuracy. R2 is mainly used to assess the goodness of fit of the regression model. Values close to 1 indicate that the regression model has a better fit to the observations. The formula for each evaluation index is as follows:

where \(\:N\) denotes the number of observations, \(\:{y}_{i}\) denotes the actual observations, \(\:{\widehat{y}}_{i}\) denotes the predicted values of the observations, and \(\:\stackrel{-}{y}\) denotes the average of the actual observations.

Results and analysis

Selection of evaluation metrics

This study initially identified twelve factors that influence groundwater potential. To assess their correlation, a Pearson correlation analysis was conducted at a 99% significance level, as illustrated in (Fig. 5). Strong correlations were noted among factors within the same category: slope with relative relief (0.79) and TWI (−0.56), drainage density and distance to rivers (−0.74), fracture distance and fault density (−0.60), NDVI and land use (−0.52). Generally, a correlation coefficient (ρ) with an absolute value exceeding 0.7 suggests the need to remove redundant variables64. However, this study adopts a more stringent threshold of 0.5 to facilitate subsequent factor overlay applications. By retaining factors with higher utilization frequency and relatively weaker correlations with alternate variables, seven evaluation indicators were selected: slope, lithology, distance to faults, spring flow, TWSC, drainage density, and land use.

Further analysis regarding multicollinearity among the selected factors is detailed in (Table 5). As a result, Pearson correlation coefficients (ρ) ranged from −0.318 to 0.281 and were statistically significant (P < 0.01). The diagnosis of multicollinearity revealed that the Tol for slope (0.807) was the lowest, and the VIF for slope (1.239) was the highest. All collinearity statistics fell within acceptable thresholds (Tol > 0.1, VIF < 10), confirming the absence of multicollinearity. These indicate that the selected factors are independent and can reliably distinguish groundwater potential anomalies without redundancy. Therefore, these indicators are deemed reliable predictor variables for GWPZ mapping and assessment.

Development of thematic layers

To facilitate the overlay analysis of GWPZs, these indicator layers were transformed into a uniform projection and resampled using ArcGIS software. The final step involved converting these indicators into thematic layers in a standardized raster data format, using the WGS-1984 UTM 50 N projected coordinate system with a 30 m spatial resolution, as shown in (Figs. 6 and 7).

Topographic and geological influencing factors for GWPZs: (a) slope, (b) lithology, (c) distance to faults, (d) spring flow using ArcMap 10.6.1 software35.

The slope in the study area ranges from 0 to 67° (Fig. 6a). Steep slopes (> 15°) cover about 40% of the area, mainly due to the surrounding mountains, while gentler slopes (< 7°) are limited to central and northeastern basins. Plains and basins with low slope values have higher water storage capacity relative to mountains with high slope values. Figure 6b illustrates that the study area spans various geological formations, predominantly Quaternary and Devonian strata. Granites of different ages are distributed along the margins. Based on the lithology and porosity characteristics of different strata (see Supplementary Table S1 online), the stratigraphic units were grouped and rated for groundwater potential. Springs were relatively evenly distributed in the mountainous areas, with 53% being small-flow springs (< 0.1 L/s). After spatial interpolation, spring flow values ranged from 0.01 to 16.20 L/s. Higher flow values, indicating better groundwater potential, were found in the central and northern parts (Fig. 6c). Significant tectonic activity, with faults widely distributed except in central basins (Fig. 6d), increases rock fragmentation near faults, enhancing groundwater recharge and infiltration rates.

Hydrological and Land cover influencing factors for GWPZs: (a) drainage density, (b) TWSC, (c) land use using ArcMap 10.6.1 software35.

The study area features long mountain ranges and undulating hills, and the steep terrain produces a dense drainage network with a density ranging from 0 to 3.23 km/km2 in (Fig. 7a). High mountain ridges exhibited lower drainage density, limiting rainfall infiltration and river recharge, and resulting in low groundwater recharge potential. In contrast, areas with high drainage density at river confluences promote faster groundwater recharge. TWSC indicates the maximum water infiltration capacity, and its larger values suggest greater groundwater storage potential. The multi-year average TWSC shows a clear northeast-to-southwest decreasing trend, with an annual maximum of 1020 mm and a changing amplitude of about 130 mm as shown in (Fig. 7b). Land use was categorized into six types (Fig. 7c), where cropland, grassland, and forest were assigned higher weights due to their high recharge rates. Conversely, artificial surfaces and bare land were assigned lower ratings due to surface runoff and lower permeability, which reduced their groundwater enrichment potential.

Detection of GWPZs

Indicator weights and subclass rating

Groundwater potential maps were created by assigning weights and ratings to thematic layers using linear weighted overlays in ArcGIS v10.6. Based on previous studies, each layer was classified into subclasses with rankings from 1 (least important) to 9 (most important) according to their impact on groundwater. Table 6 presents the classification and ranking of these layers, along with essential references. The analysis of wells situated in subclasses rated medium or higher (rank > 5) across various thematic layers indicates that all proportions exceed 61%, with a maximum of 100% and an average of 85%. This properly demonstrates the accuracy of the ranking of thematic layers.

Determining the weights of evaluation indicators is a critical component for GWPZ detection using the AHP and FAHP methods. This study systematically employed impact levels on groundwater, derived from the extensive literature review, as the foundational basis for decision-making (see Table 2). Subsequently, it integrated expert opinions and methodologies from mountain groundwater surveys to accurately assess and recalibrate the relative significance of these indicators. To this end, the pairwise comparison matrices for both models were meticulously constructed, as shown in (Fig. 8). Subsequent consistency tests revealed that the consistency ratio (CR CI/RI = 0.021/1.32) was 0.016 (< 0.1) for the AHP model, which satisfied logical consistency requirements, validating the reliability of the AHP-derived weights. The FAHP model used the same semantic scale as AHP and was thus also assumed to satisfy consistency requirements.

Normalized weights for thematic layers were computed for both methods and are summarized in (Table 6). Larger values of weights indicate that the evaluation indicator has a greater impact on groundwater potential. In YDC, lithology was the most influential factor, with weights of 32.51% (AHP) and 24.28% (FAHP), followed by slope (28.32 and 21.18%, respectively) and drainage density (15.78 and 16.82%, respectively). Other factors had weights below 15%, with their relative importance ranked as follows: fault distance > spring flow > TWSC > land use.

Weighted overlay analysis

Based on the indicator weights estimated by AHP and FAHP models and the subclass ratings by expert decision-making, the normalized weights of factors and features were integrated into the corresponding thematic layers using GIS reclassification. GWPI for each pixel was calculated using a weighted linear combination approach according to formula (20). To maximize inter-category variation, natural breaks classification was applied, resulting in five GWPZ categories: very low, low, medium, high, and very high, as illustrated in (Fig. 9a, b). The area distribution of these categories is detailed in (Fig. 9c).

Groundwater potential distribution in YDC: (a) AHP; (b) FAHP; (c) Area of different zones using ArcMap 10.6.1 software35.

GWPI values were in the ranges of 0.112–0.306 (AHP) and 0.118–0.298 (FAHP). The proportions of areas classified as very high potential were 13.92 and 14.33%, while high-potential areas accounted for 26.29 and 27.55%, respectively. Medium-potential zones accounted for 29.33% (AHP) and 28.14% (FAHP), followed by low-potential zones (20.66 and 21.50%) and very low-potential zones (9.80 and 8.48%). The high correlation coefficient (ρ = 0.977) between the two assessments indicates that they have similar spatial distributions.

Model validation of AHP and FAHP

To validate the precision of the actual GWPZ delineation, measured borewells and spring data were superimposed on the GWPZ map, and the model prediction accuracy was assessed using the ROC curve. This curve is widely regarded as a robust tool for evaluating the performance of binary classification models, with the AUC serving as a performance metric that does not depend on a specific threshold. Due to the absence of a globally accepted principle for evaluating groundwater potential using spring or drilling water influx data, this study adopted a standard groundwater richness classification commonly employed in hydrogeological investigations in China. Specifically, when the drilling water influx is ≥ 100 m3/d or the spring flow rate is ≥ 0.1 L/s, the corresponding water-bearing rock group is classified as moderately or highly water-rich19. Based on this criterion, 81 testing sites (28 drilled wells and 53 springs) were labeled as either possessing or lacking groundwater potential. The ROC curves for both models are illustrated in (Fig. 10).

GWPZ detection aims to facilitate groundwater development by converting the qualitative description of potential zones into quantitative characterizations of accessible water quantities. Predicting water outflows in high GWPZs has significant practical value. In this study, the quantitative relationship between drilling water influx and the GWPI was explored. This study explored the quantitative relationship between drilling water influx and GWPI, and validated model performance using accuracy indicators. Experimental results revealed that the logarithmic values of GWPI and borewell yield exhibited a distinct linear relationship, meaning that the groundwater potential and drilled yield conform to an exponential function model, as shown in (Fig. 11). Table 7 summarizes the statistical prediction performance metrics of the AHP and FAHP models.

As detailed in Table 7, the ROC analysis yielded AUC values of 84.41% for AHP and 85.09% for FAHP. An AUC exceeding 80% is generally indicative of a highly accurate groundwater potential assessment model65. These findings confirm the reliability of both AHP and FAHP in GWPZ detection. The FAHP model, with R2 value of 0.817, exhibited a better fit compared to the AHP model (R2 = 0.747). The R2 differences were also tested using the Bootstrap method66, yielding a P-value of 0.02 (< 0.05), which indicates that this improvement is statistically significant. Additionally, other performance indicators in (Table 7), such as lower error values for FAHP, emphasize its better prediction performance, thereby confirming its advantages in improving the accuracy of groundwater potential mapping.

Sensitivity analysis of indicators

Sensitivity analysis is an effective technique for determining the degree of variability in model outputs due to individual factors. In this study, the sensitivity was evaluated by analyzing the proportion of model output results accounted for by individual factors. The effective weights are presented in (Table 8).

The results reveal numerical deviations between the effective and empirical weights, but the ranking of factor influence remains within an acceptable range. Lithology, slope, and drainage density were still the most influential factors, with effective weights of 26.57, 22.60, and 14.43%, respectively. These factors are more dominant in mountainous terrain than in the plains, which also confirms that topography, geology, and water system characteristics are the key exploration targets in groundwater potential assessments in mountainous areas. Factors such as distance to faults (12.31%) and spring flow (9.07%) exhibited moderate sensitivity. Although these parameters have lower effective weights, their control on groundwater storage and movement should not be ignored for the exploration of groundwater potential in mountainous areas. Conversely, TWSC (7.99%) and land use (7.03%) were identified as low-sensitivity parameters. Despite its low weight, the influence of land use was nevertheless evident. The impact of TWSC was limited by the lower spatial resolution of precipitation and other meteorological variables, thus reducing its apparent effect on groundwater. In conclusion, this study has demonstrated the reliability and applicability of the selected seven indicators for assessing groundwater potential in regions such as YDC by integrating the correlation and sensitivity analyses of the factors.

Typical water enrichment types

Based on the degree of influence of various factors on groundwater potential, this study identified four primary types of groundwater-enriched areas for hilly and mountainous areas: catchment basins, riverine zones, fractured hard rocks, and water-enriched karst areas. These types were defined by integrating three-dimensional topographic, fracture, and river data, along with field investigations of drilled wells with significant water influx that had been constructed and put into service. Using the groundwater prediction model and field investigations, we obtained the spatial distribution of predicted water influx and representative water-enriched regions, as shown in (Fig. 12). The characteristics of each type in the study area are elaborated as follows:

Predicted groundwater influx and distribution of typical water enrichment types using ArcMap 10.6.1 software35.

-

(1)

Catchment basins are characterized by surface water accumulation due to low-lying topography near mountainous regions, coupled with dense surface water systems. Such areas exhibit strong groundwater enrichment, as depicted as Type I. Topographic and hydrological factors, such as slope and drainage density, are the primary controlling factors.

-

(2)

In riverine zones, groundwater enrichment is attributed to loose Quaternary rock layers, which exhibit high permeability, and the strong water cycle interactions near rivers. During periods of high water availability, groundwater is fully recharged, and even if the groundwater evaporates and is discharged slowly during droughts, the water yield is still higher. Lithology and surface water systems primarily control these zones, depicted as type II.

-

(3)

Fractured hard rocks are underlain by fractured hard rock strata, which provide excellent recharge and transport channels for groundwater. Abundant groundwater reserves form after surface water recharge, making lithology and fault tectonics the dominant controlling factors. This type is predominantly distributed in granite regions, are shown as type III.

-

(4)

Water-enriched karst areas are characterized by groundwater movement and storage in karst landscapes, often in the form of underground rivers and reservoirs. Carbonate rocks serve as the primary control, with dense spring distributions or significant water inflows aiding in their identification. This type is depicted as Type IV in the study area.

Notably, the marked regions represent the most water-rich areas, while the scattered, unlabeled zones predominantly correspond to riverine and catchment basin types in (Fig. 12).

Discussion

The limitation of model assumptions

This study utilized two models based on expert judgment, AHP and FAHP, to detect GWPZs. However, the model assumptions have inherent limitations. As knowledge-driven approaches, they are predominantly reliant on subjective opinions, which may introduce various biases. While this study confirms that FAHP has a slight advantage over AHP based on limited drilling data, the adopted method does not entirely mitigate these limitations. In light of recent advancements in machine learning techniques, there exists substantial potential to enhance GWPZ assessment methodologies. Recent work by Sadeghi et al.24 indicates that integrating physics-based methods with machine learning in hybrid models may improve the performance of deep learning models in GWPZ mapping. Furthermore, specific strategies that amalgamate machine learning with knowledge-driven approaches have shown considerable promise. These include leveraging expert knowledge to enhance model accuracy, implementing rule-based systems to guide machine learning algorithms, and utilizing ontologies for data structuring to improve contextual understanding. Such methodologies mitigate human influence in traditional approaches and address non-linearity and multiple regression issues. Representing essential research directions for future robust groundwater evaluations, these strategies underscore the necessity for extensive validation to ensure their efficacy.

Data constraints

The data constraints consist of two primary parts. Firstly, the uncertainty inherent in the original datasets introduces errors in the mapping results. This issue is particularly pronounced in remote sensing data, where inadequate or erroneous information can result in biased conclusions. Although this study has implemented several strategies, including utilizing widely recognized datasets with high accuracy, conducting correlation analyses to mitigate potential factor interactions, and resampling to standardize resolution, some degree of error remains unavoidable. In future research targeting specific regions, it is advisable to assess the consistency and reliability of various satellite images, along with a comparative analysis of spatial interpolation using field data from authoritative institutions. Such measures aim to reduce these errors further and enhance the mapping precision of GWPZs.

Additionally, the difficulty in obtaining key data has led to the absence of some important impact indicators. Based on publicly available data, this study established seven evaluation factors. However, these indicators serve as indirect measures of groundwater potential. Certain indicators, such as aquifer thickness, resistivity, soil permeability, and groundwater depth, which could provide direct insights into groundwater characteristics, were excluded primarily due to issues with data availability and collection difficulties. This unfortunate deficiency underscores the need for future research endeavors to gather relevant data, validate its application, and enhance its utility in groundwater assessments.

Comparison with other studies

Investigating the changes in groundwater availability influenced by human activities and climate dynamics is crucial for planning decisions to mitigate related risks, particularly in regions vulnerable to natural disasters and climatic variability. A recent study by Tiwari et al.67 employed various parameters, specifically analyzing rainfall, groundwater levels, and land use across different periods, to develop spatiotemporal maps of groundwater potential zones in Ajmer City, India. This provides a clear approach for exploring seasonal or long-term changes in groundwater potential under climate influences. While this research primarily focuses on urgent water supply demands, it has not conducted relevant research due to the lack of timely collection of long-term time series data for related indicators. This issue is acknowledged and will be rectified in future research efforts. Moreover, existing research results have underscored the significance of groundwater’s social attributes, as there is a close relationship between socio-economic variables and water access68. Socio-economic factors such as population density, income levels, and industrial structure are pivotal in determining water accessibility and vulnerability. Addressing these critical research topics requires further data support that will be pursued in subsequent studies.

Application of research findings

In China, groundwater potential assessment has traditionally focused on regions with severe water scarcity and frequent disasters. For example, Zhang et al.36 studied the Sichuan Province in Southwestern China, known for its susceptibility to earthquakes, while Deng et al.19 and Shao et al.27 examined the semi-arid Liaoning Province in Northeast China and Shanxi Province in northern China, respectively. In contrast, this paper addresses the southern hilly areas characterized by abundant water resources but seasonal shortages, thereby filling a gap in the existing literature. Additionally, their methods relied solely on AHP or FAHP models without comparative validation, and their selected indicators varied based on regional characteristics. Our research findings also incorporate practical applications in locating water sources, which is less common in other studies.

Under the support of drinking water safety project of China geological survey, we conducted groundwater exploration in key villages of YDC facing severe water shortages. Our findings provided timely information on potential groundwater resources, narrowing down geophysical exploration and drilling efforts to yield well locations that are abundant and accurately positioned, as shown in (Fig. 13). The detailed account of the geophysical exploration process is available in our other published work69. These initiatives ensure a reliable drinking water supply for local residents and meet agricultural irrigation needs, contributing to YDC becoming a national model county for safe drinking water. The integration of groundwater potential assessments with geophysical methods reduces costs and provides a novel approach for precise water sourcing. However, despite some applications of our findings, there is still a need for cross-regional adaptive research. Therefore, we plan to expand these applications to validate our methodologies further.

Integrated application of GWPZ maps and geophysical methods for rapid and accurate water exploration in YDC69.

Conclusion

This study employed a GIS platform to integrate multi-source datasets, including remote sensing, geology, and hydrology, to delineate GWPZs in YDC. The MCDA techniques were also applied to enhance the mapping process. To validate the proposed methodology, borewell data were systematically compared, enabling yield predictions and performance evaluations. The specific conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

Seven indicators influencing groundwater potential were identified: slope, lithology, distance to faults, spring flow, TWSC, drainage density, and land use. These factors have proven economical and practical based on publicly available data and rigorous correlation analysis. Sensitivity analysis elucidated the degree of influence of different factors for GWPZs, highlighting that lithology, slope, and drainage density are the most significant contributors to this typical mountainous terrain.

-

(2)

The reliability of combining GIS with AHP and FAHP to delineate GWPZs was confirmed. There is a minimal spatial variation between the results derived from the AHP and FAHP models. The accuracy of the FAHP model (85.09%), measured by the AUC of the ROC, was slightly better than that of AHP (84.41%). The yield prediction model also showed a stronger correlation coefficient for FAHP (R2 of 0.817) than that of AHP (R2 of 0.747). These results confirm that the FAHP model is more effective in delineating GWPZs.

-

(3)

The GWPZ maps for YDC were constructed and categorized into five levels: very high (13.92% for AHP and 14.33% for FAHP), high (26.29 and 27.55%), medium (29.33 and 28.14%), low (20.66 and 21.50%) and very low (9.80 and 8.48%). Four primary types of groundwater-enriched areas in hilly and mountainous regions have also been identified: catchment basins, riverine zones, fractured hard rocks, and water-enriched karst areas. Relevant maps have been utilized to enhance groundwater development in water-scarce villages, resulting in substantial benefits.

This study significantly contributes to understanding the groundwater potential in YDC. The generated maps can be used as an initial framework for local authorities in planning for prospective groundwater areas, emergency water sources, and ecological protection zones. Due to limitations such as model assumptions, future research will explore groundwater potential using advanced artificial intelligence methods, including physics-constrained integration and heterogeneous model fusion. Additionally, the socio-economic variables and time series data should be integrated as a criterion to enhance water resource accessibility and potential applications. The findings of this study establish a solid foundation for identifying target areas for emergency groundwater development, thereby facilitating focused drilling activities. Furthermore, these results support informed decision-making for improving storage quantity and conditions for sustainable groundwater management and ensuring long-term water security in similar mountainous environments.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kaliyappan, S. P., Hasher, F. F., Abdo, B. H. G., Kumar, P. J. S. & Paneerselvam, B. A novel integrated approach to assess groundwater appropriateness for agricultural uses in the Eastern coastal region of India. Water 16 (18), 2566 (2024).

Oki, T. & Kanae, S. Global hydrological cycles and world water resources. Science 313 (5790), 1068–1072 (2006).

Gebeyehu, A., Ayenew, T. & Asrat, A. Delineation of groundwater potential zones of the transboundary aquifers within the semiarid Bulal catchment, Southern Ethiopia. Environ. Monit. Assess. 195 (4), 458 (2023).

Fang, Y. & Ying, B. Spatial distribution of mountainous regions and classifications of economic development in China. J. Mt. Sci. 13 (6), 1120–1138 (2016).

Yin, Z. et al. Variations of groundwater storage in different basins of China over recent decades. J. Hydrol. 598, 126282 (2021).

Zhang, Z. et al. Groundwater potential assessment in Gannan region, China, using the soil and water assessment tool model and GIS-based analytical hierarchical process. Remote Sens. 15 (15), 3873 (2023).

Guan, Y. et al. Tracing anomalies in moisture recycling and transport to two record-breaking droughts over the mid-to-lower reaches of the Yangtze river. J. Hydrol. 609, 127787 (2022).

Lubang, J., Liu, H. & Chen, R. Combined application of hydrogeological and geoelectrical study in groundwater exploration in karst-granite areas, Jiangxi Province. Water 15 (5), 865 (2023).

Ranjan, P., Pandey, P. K. & Pandey, V. Groundwater spring potential zonation using AHP and fuzzy-AHP in Eastern Himalayan region: Papum Pare district, Arunachal Pradesh, India. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 31 (7), 10317–10333 (2024).

Chatterji, P. C. & Singh, S. A proposed photohydrogeomorphic technique as an aid for faster exploration of groundwater potential areas in the Indian arid zone. Ann. Arid Zone. 19 (1–2), 58–64 (1980).

Sreedevi, P. D., Subrahmanyam, K. & Ahmed, S. The significance of morphometric analysis for obtaining groundwater potential zones in a structurally controlled terrain. Environ. Geol. 47 (3), 412–420 (2005).

Sonkamble, S., Satishkumar, V., Amarender, B. & Sethurama, S. Combined ground-penetrating radar (GPR) and electrical resistivity applications exploring groundwater potential zones in granitic terrain. Arab. J. Geosci. 7 (8), 3109–3117 (2014).

Gomo, M. Exploring deeper groundwater in a dolomite aquifer using telluric electric frequency selection method geophysical approach. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 26, 101265 (2024).

Zheng, Z. et al. Integrated geophysical methods for ground water prospecting in fault fracture zones under low-resistivity background conditions: a case study from Laohutiangou village, Xuanwei, Yunnan Province. Earth Sci. Inf. 18 (2), 209 (2025).

Gori, F. et al. Groundwater–rock interactions and mixing in fault–controlled karstic aquifers: A structural, hydrogeochemical and multi-isotopic review of the Pontina plain (Central Italy). Sci. Total Environ. 951, 175439 (2024).

Welch, L. A. & Allen, D. M. Hydraulic conductivity characteristics in mountains and implications for conceptualizing bedrock groundwater flow. Hydrogeol. J. 22 (5), 1003–1026 (2014).

Segura, C. et al. Climate, landforms, and geology affect baseflow sources in a mountain catchment. Water Resour. Res. 55 (7), 5238–5254 (2019).

Shaddoud, M. A., Costache, R., Kotaridis, I., Fereshtehpour, M. & Kuriqi, A. Flash flood prioritization assessment using morphometric analysis in the coastal region of the Eastern mediterranean. DYSONA - Appl. Sci. 6 (1), 172–185. https://doi.org/10.30493/das.2024.480819 (2025).

Deng, F. et al. Application of remote sensing and GIS analysis in groundwater potential Estimation in West Liaoning Province, China. J. Eng. Res. 4 (3), 1–17 (2016).

Goodchild, M. F. Geographical information science. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 6 (1), 31–45 (1992).

Malczewski, J. GIS-based multicriteria decision analysis: a survey of the literature. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 20 (7), 703–726 (2006).

Golkarian, A., Naghibi, S. A., Kalantar, B. & Pradhan, B. Groundwater potential mapping using C5.0, random forest, and multivariate adaptive regression spline models in GIS. Environ. Monit. Assess. 190 (3), 149 (2018).

Morgan, H., Madani, A., Hussien, H. M. & Nassar, T. Using an ensemble machine learning model to delineate groundwater potential zones in desert fringes of East Esna-Idfu area, nile Valley, upper Egypt. Geosci. Lett. 10 (1), 9 (2023).

Sadeghi, B., Alesheikh, A. A., Jafari, A. & Rezaie, F. Performance evaluation of convolutional neural network and vision transformer models for groundwater potential mapping. J. Hydrol. 654, 132840 (2025).

Saaty, T. L. Decision making with the analytic hierarchy process. Int. J. Serv. Sci. 1 (1), 83–98 (2008).

Swetha, T. V., Gopinath, G., Thrivikramji, K. P. & Jesiya, N. P. Geospatial and MCDM tool mix for identification of potential groundwater prospects in a tropical river basin, Kerala. Environ. Earth Sci. 76 (12), 428 (2017).

Shao, Z., Huq, M. E., Cai, B., Altan, O. & Li, Y. Integrated remote sensing and GIS approach using Fuzzy-AHP to delineate and identify groundwater potential zones in semi-arid Shanxi Province, China. Environ. Modell Softw. 134, 104868 (2020).

Jenifer, M. A. & Jha, M. K. Comparison of analytic hierarchy process, catastrophe and entropy techniques for evaluating groundwater prospect of hard-rock aquifer systems. J. Hydrol. 548, 605–624 (2017).

Fijani, E., Hayati, S. & Mozafari, M. Prospectivity modeling of karstic groundwater in the Southeast of Damavand Mountain, Iran. Geopersia 12 (1), 141–151 (2022).

Arabameri, A., Rezaei, K., Cerda, A., Lombardo, L. & Rodrigo-Comino, J. GIS-based groundwater potential mapping in shahroud plain, Iran. A comparison among statistical (bivariate and multivariate), data mining and MCDM approaches. Sci. Total Environ. 658, 160–177 (2019).

Ikirri, M. et al. Delineation of groundwater potential area using an AHP, remote sensing, and GIS techniques in the Ifni basin, Western Anti-Atlas, Morocco. Water 15 (7), 1436 (2023).

Mallick, J. et al. Modeling groundwater potential zone in a semi-arid region of Aseer using fuzzy-AHP and geoinformation techniques. Water 11 (12), 2656 (2019).

Suryawanshi, S. L. et al. Spatial and decision-making approaches for identifying groundwater potential zones: a review. Environ. Earth Sci. 82 (20), 463 (2023).

Ying, B., Ke, L., Zhu, F. & He, N. Towards differentiated development policies for mountainous areas: A Spatial analysis of mountain distribution and characteristics in a geographic region. Land. Degrad. Dev. 34 (16), 5071–5082 (2023).

ArcGIS. https://desktop.arcgis.com/zh-cn/arcmap/10.6/get-started/setup/arcgis-desktop-quick-start-guide.htm (2018).

Zhang, Q. et al. GIS-based groundwater potential assessment in varied topographic areas of Mianyang City, Southwestern China, using AHP. Remote Sens. 13 (22), 4684 (2021).

Tang, G., Clark, M. P., Papalexiou, S. M., Ma, Z. & Hong, Y. Have satellite precipitation products improved over last two decades? A comprehensive comparison of GPM IMERG with nine satellite and reanalysis datasets. Remote Sens. Environ. 240, 111697 (2020).

Hasan, F., Medley, P., Drake, J. & Chen, G. Advancing hydrology through machine learning: insights, challenges, and future directions using the CAMELS, caravan, GRDC, CHIRPS, PERSIANN, NLDAS, GLDAS, and GRACE datasets. Water 16 (13), 1904 (2024).

Luo, D., Wen, X., Zhang, H., Xu, J. & Zhang, R. An improved FAHP based methodology for groundwater potential zones in Longchuan river basin, Yunnan Province, China. Earth Sci. Inf. 13 (3), 847–857 (2020).

Madani, A. & Niyazi, B. Groundwater potential mapping using remote sensing and random forest machine learning model: a case study from lower part of Wadi Yalamlam, Western Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 15 (3), 2772 (2023).

Chen, J., Cao, X., Peng, S. & Ren, H. Analysis and applications of GlobeLand30: a review. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 6 (8), 230 (2017).

Jin, X., Liu, J., Wang, S. & Xia, W. Vegetation dynamics and their response to groundwater and climate variables in Qaidam basin, China. Int. J. Remote Sens. 37 (3), 710–728 (2016).

Burayu, D. G., Karuppannan, S. & Shuniye, G. Geospatial mapping of groundwater potential zones using multi-criteria decision analysis and GIS fuzzy logic in Dabus Sub-Basin, Western Ethiopia. Quat Sci. Adv. 18, 100275 (2025).

Mohammed, S. H. et al. Integrating Geospatial, hydrogeological, and geophysical data to identify groundwater recharge potential zones in the Sulaymaniyah basin, NE of Iraq. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 9920 (2025).

Pitchaimani, V. S., Joe, R. J. J., Abishek, S. R., Aswin, S. K. & Narayanan, M. S. S. Integrating AHP and Geospatial data analysis for mapping groundwater potential in tropical coastal villages of Thiruvananthapuram, Southern India. J. Coast Conserv. 29 (1), 1 (2025).

Tasci, S. et al. Geospatial and multi-criteria analysis for identifying groundwater potential zones in the Oltu basin, Turkey. Water 17 (2), 240 (2025).

Chavda, Z. K., Kakwani, D. & Singh, N. Delineation of groundwater potential zones in Narmada district Gujarat (India) using GIS and AHP techniques. Water Conserv. Sci. Eng. 9 (1), 7 (2024).

El-Sorogy, A. S., Alharbi, T., Al-Kahtany, K., Rikan, N. & Salem, Y. Identification and validation of groundwater potential zones in Al-Madinah Al-Munawarah, Western Saudi Arabia using remote sensing and GIS techniques. Water 16 (23), 3421 (2024).

Osumeje, J. O., Eshimiakhe, D., Oniku, A. S. & Lawal, K. M. Application of remote sensing and electrical resistivity technique for delineating groundwater potential in North Western Nigeria. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 22299 (2024).

Bhadran, A. et al. A GIS based Fuzzy-AHP for delineating groundwater potential zones in tropical river basin, Southern part of India. Geosyst. Geoenviron. 1 (4), 100093 (2022).

Abdo, H. G. et al. GIS-based multi-criteria decision making for delineation of potential groundwater recharge zones for sustainable resource management in the Eastern mediterranean: a case study. Appl. Water Sci. 14 (7), 160 (2024).

Ogungbade, O. et al. A combined GIS, remote sensing and geophysical methods for groundwater potential assessment of Ilora, Oyo central, Nigeria. Environ. Earth Sci. 81 (3), 74 (2022).

Rather, A. F. et al. Mapping of groundwater potential zones in Pohru watershed of Jhelum Basin-Western Himalaya, India using integrated approach of remote sensing, GIS and AHP. Earth Sci. Inf. 15 (4), 2091–2107 (2022).

Allafta, H., Opp, C. & Patra, S. Identification of groundwater potential zones using remote sensing and GIS techniques: a case study of the Shatt Al-Arab basin. Remote Sens. 13 (1), 112 (2021).

Dar, T., Rai, N. & Bhat, A. Delineation of potential groundwater recharge zones using analytical hierarchy process (AHP). Geol. Ecol. Landsc. 5 (4), 292–307 (2021).

Doke, A. B., Zolekar, R. B., Patel, H. & Das, S. Geospatial mapping of groundwater potential zones using multi-criteria decision-making AHP approach in a hardrock basaltic terrain in India. Ecol. Indic. 127, 107685 (2021).

Halder, S., Roy, M. B. & Roy, P. K. Fuzzy logic algorithm based analytic hierarchy process for delineation of groundwater potential zones in complex topography. Arab. J. Geosci. 13 (13), 574 (2020).

Xie, J., Xu, Y., Gao, C., Xuan, W. & Bai, Z. Total basin discharge from GRACE and water balance method for the Yarlung Tsangpo river basin, Southwestern China. J. Geophys. Res. -Atmos. 124 (14), 7617–7632 (2019).

Kumar, T., Gautam, A. K. & Kumar, T. Appraising the accuracy of GIS-based Multi-criteria decision making technique for delineation of groundwater potential zones. Water Resour. Manag. 28 (13), 4449–4466 (2014).

Nag, S., Roy, M. B. & Roy, P. K. Study on the functionality of land use land cover over the evaluation of groundwater potential zone: A fuzzy AHP based approach. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 131 (3), 146 (2022).

Van Laarhoven, P. J. M. & Pedrycz, W. A fuzzy extension of Saaty’s priority theory. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 11 (1–3), 229–241 (1983).

Buckley, J. J. Fuzzy hierarchical analysis. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 17 (3), 233–247 (1985).

Ragragui, H. et al. Mapping and modeling groundwater potential using machine learning, deep learning and ensemble learning models in the Saiss basin (Fez-Meknes region, Morocco). Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 26, 101281 (2024).

Shrestha, N. Detecting multicollinearity in regression analysis. Am. J. Appl. Math. Stat. 8 (2), 39–42 (2020).

Maity, B., Mallick, S. K., Das, P. & Rudra, S. Comparative analysis of groundwater potentiality zone using fuzzy AHP, frequency ratio and bayesian weights of evidence methods. Appl. Water Sci. 12 (4), 63 (2022).

Cameron, A. C., Gelbach, J. B. & Miller, D. L. Bootstrap-based improvements for inference with clustered errors. Rev. Econ. Stat. 90 (3), 414–427 (2008).

Tiwari, V., Kumar, A. & Mukherjee, M. Spatiotemporal mapping of groundwater recharge potential zones for physical planning process-A case of Ajmer City, India. Ecohydrol Hydrobiol. 25 (1), 184–205 (2025).

Bhowmik, D., Kader, Z., Hosen, B. & Hossain, S. Exploring socioeconomic vulnerability and natural disasters impacts on water access in Southwestern Bangladesh. DYSONA - Appl. Sci. 6 (1), 186–199. https://doi.org/10.30493/das.2024.483646 (2025).

Dai, Z. et al. Studying on the joint method in groundwater exploration in mountainous area based on DEM and high-density resistivity. Int. Core J. Eng. 10 (6), 146–158 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42074176) and the Technology Innovation Guidance Program of Jiangxi Province (No. 2022KSG01003). The authors are also thankful to the Wuhan Center of China Geological Survey, for providing data for the analysis and the invaluable suggestion from experts in the field of hydrogeology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.C. and S.Z. conceived the idea for the study and drafted the main manuscript text. S.L. and M.L. prepared the code and conducted data analysis. T.W. and T.Z. provided supervision and visualization support. X.B. checked English grammar and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, M., Zhang, S., Liu, S. et al. Mapping the groundwater potential zones in mountainous areas of Southern China using GIS, AHP, and fuzzy AHP. Sci Rep 15, 17159 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01837-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01837-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Integration of geospatial techniques and artificial neural networks for groundwater potential zonation in India

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

Geophysical and multi-criteria decision methods for delineating groundwater potential in coastal terrains: a study from Port Sudan

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

Unraveling the hydrochemical characteristics and assessing health risk of groundwater in the Luanhe River Piedmont Alluvial Fan Complex, an industrial-agricultural transition zone in North China

Environmental Geochemistry and Health (2026)

-

Integrated assessment of groundwater potential and quality in a seismically active Himalayan city: a case study from Muzaffarabad, Pakistan

Environmental Geochemistry and Health (2026)

-

Disappearing streams and morphometric degradation in small watersheds of the Ganga River basin

Discover Water (2026)