Abstract

Abdominal aortic calcification (AAC) and atherosclerosis are prevalent conditions among older adults, and recent research suggests that their association may extend beyond the effects of aging alone. An essential instrument for determining the possibility of cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the cardiometabolic index (CMI), a new lipid-based index sensitive to visceral obesity. However, little has been established about the relationship between CMI and AAC. We examined CMI and AAC data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) conducted in 2013–2014 for this study. The relationship between AAC, severe abdominal aortic calcification (SAAC), and CMI was assessed using multiple linear and logistic regression models. The overall trend was visualized using smoothed curve modeling. Subgroup analyses were conducted to find possible moderating factors. Among the 2704 participants included, those with higher CMI levels exhibited much greater AAC scores and a higher prevalence of SAAC. In model 3, elevated CMI positively correlated with AAC (0.25 (0.09, 0.41)) and with the odds of SAAC (OR = 1.35 (1.09, 1.67)). Participants in the highest CMI quartile had an AAC score that was 0.65 units higher (β = 0.65 (0.26, 1.04)) and an 114% higher risk of SAAC (OR = 2.14 (1.29, 3.54)). Subgroup analyses indicated sex and smoking status significantly modified the relationship between CMI, AAC, and SAAC, while previously diagnosed with congestive heart failure (CHF) and heart attack significantly moderated the association between CMI and AAC. These results imply that greater AAC scores and a higher risk of SAAC are linked to heightened CMI, which represents visceral fat storage and disturbed lipid metabolism. Our findings indicate that CMI is correlated with AAC in certain demographic and cardiovascular subgroups, suggesting its potential as an exploratory indicator of elevated AAC risk in these populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An abnormal buildup of crystallization of calcium within the intima of the artery is a hallmark of vascular calcification1. This accumulation in the arterial wall might constrict the aorta’s lumen and make it more stiff. Furthermore, lipid-rich deposits build up and solidify along the vessel walls to create atherosclerotic plaques, which are facilitated by calcium deposits. Plaque calcification over time may impede blood flow, increasing the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD)2,3. AAC, a common manifestation of vascular calcification4, develops earlier than coronary artery calcification (CAC) and may serve as a sign of vascular morbidity and mortality. Research indicates that AAC can independently predict subclinical CVD and anticipated cardiovascular risks, unrelated to traditional risk factors5,6,7. The cardiovascular consequences of AAC and CAC were examined by the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Only AAC was found to be significantly linked to CVD mortality, despite the fact that both CAC and AAC were independent predictors of CVD and coronary heart disease (CHD). Additionally, AAC outperformed CAC as a predictor of all-cause death8. Consequently, reducing the incidence and prevalence of CVD requires effective handling and the avoidance of AAC9.

Globally, Obesity is now a significant public health challenge10. As reported by studies, 11.1% of mortality caused by non-infectious diseases is attributable to overweight or obesity11,12. Despite being widely used to evaluate the CVD risk linked to obesity, the amount and location of body fat are not properly described by body mass index (BMI), and BMI does not take into consideration changes in hydration status and fails to discern whether weight changes are due to preserved or increased lean mass or elevated fat mass13,14,15. In CHF, visceral fat deposits are acknowledged as a more robust indicator of death risk than BMI-defined obesity14,16. The CMI has been used to screen for both obesity and diabetes. It incorporates obesity indicators, such as the triglyceride-to-HDL cholesterol ratio and the waist-to-height ratio (WHtR), to evaluate visceral obesity17. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), hyperuricemia, chronic kidney disease (CKD), CVD, and stroke are all linked to CMI18,19,20,21,22.

No clinical research has been performed to evaluate the correlation between CMI and AAC. We tested the hypothesis that an elevated CMI is positively connected with the likelihood of having AAC by using 2013–2014 NHANES data in order to close this gap.

Methods

Survey description and study population

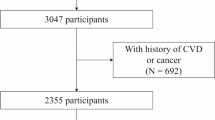

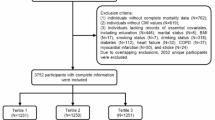

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) administers the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), A comprehensive survey program designed to assess the health status of the American population. The research began with an enrollment of 10,175 individuals. Following the removal of individuals lacking AAC scores (n = 7,035) and CMI components (total: n = 179; waist circumference: n = 39; standing height: n = 22; HDL: n = 104; TG: n = 14), as well as participants with incomplete covariate information (n = 257)—covering variables such as poverty-to-income ratio (PIR) (n = 235), BMI (n = 2), education level (n = 2), marital condition (n = 1), smoking (n = 1), CHF (n = 5), angina pectoris (n = 5), heart attack (n = 3), CHD (n = 1), and stroke (n = 2)—the final analytical sample comprised 2,704 participants. A flowchart was provided in Fig. 1.

Definition of CMI and AAC

The CMI is calculated using the WHtR and participants’ lipid profiles. The formula is as follows:

The AAC score, which was measured using the Kauppila scoring method, was used to evaluate the severity of AAC. Using the Densitometer Discovery A (Hologic, Marlborough, MA, USA), lateral lumbar spine images acquired by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) were analyzed. More severe calcification is indicated by higher total AAC scores, which range from 0 to 24. According to earlier research, an AAC score of more than 6 was considered SAAC, which is a widely accepted cutoff point for detecting substantial aortic calcification.

The research designated CMI as the primary exposure variable, whereas the AAC score and SAAC were analyzed as outcome variables.

Covariates

Demographics, economic position, metabolic markers, and comorbidities were deemed confounding factors based on their clinical importance. Among the covariates evaluated in this study are age, sex, race, BMI, PIR, educational background, smoking status, marital condition, standing height, waist circumference, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), serum phosphorus, serum calcium, Serum Creatinine (Scr), total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and triglycerides (TG) were significant factors. Additionally, we accounted for the presence of comorbid conditions, including hypertension, diabetes, Chronic kidney disease (CKD), CHF, angina pectoris, heart attack, CHD, and stroke. Supplementary Table 1 contains information on the covariates, while the measurement protocols are publicly accessible through www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/.

Statistical analysis

This analysis utilized R software alongside EmpowerStats (http://www.empowerstats.com), with a two-sided P-value < 0.05 for statistical significance.

Mean ± standard deviation (SD) was employed to describe continuous variables, while proportions were used for categorical variables. The CMI data were normalized using a log2 transformation to guarantee an equitable distribution. Differences across quartiles of the CMI for continuous variables were assessed using Student’s t-tests, and chi-square tests were employed for categorical variables. To investigate the relationship between CMI and AAC, multivariable linear regression models were used and logistic regression models were employed for the analysis of CMI and SAAC. The model 1 was unadjusted, the model 2 included adjustments for sex, age, and race, and the model 3 accounted for sex, age, race, educational background, marital condition, PIR, BMI, smoking status, total cholesterol, serum phosphorus, serum calcium, CKD, hypertension, diabetes, CHF, angina pectoris, CHD, heart attack, and stroke. Trend tests were conducted to evaluate associations across CMI quartiles. Subgroup analyses assessed the relationships between CMI, AAC, and SAAC by stratifying participants according to sex, diabetes status, smoking status, CKD, hypertension, angina, heart attack, CHD, stroke, or CHF. Interaction tests examined associations within these subgroups, with covariates from model 3 included in the analyses. Additionally, to visualize the trends, smoothed curve fitting was conducted.

Results

Baseline characteristics of participants

This analysis incorporated data from 2,704 participants, with a median age of 58.52 ± 11.99 years. The sample comprised 48.56% male and 51.44% female participants. The racial and ethnic distribution included 45.71% non-Hispanic white. The mean ± SD values for the CMI and AAC across all participants were 0.97 ± 1.35 and 1.63 ± 3.51, respectively. Clinical characteristics by CMI quartiles are detailed in Table 1. Mexican American men were overrepresented in the highest CMI quartile. Additionally, individuals with elevated CMI tended to have lower education and income, higher smoking prevalence, increased BMI and waist circumference, and elevated levels of TC, and TG. This group also had a higher risk of diabetes, hypertension, CHD, and CHF, alongside lower HDL-C levels.

The association between CMI and AAC

Table 2 shows that higher CMI scores are linked to greater AAC scores and an increased likelihood of SAAC. CMI and AAC scores showed a positive correlation in model 3 (β = 0.25 (0.09, 0.41)), indicating that each one-unit increase in CMI corresponds to a 0.25 unit increase in AAC scores. The study authors stratified CMI into quartiles, revealing a significant relationship between the highest quartile (Q4) and AAC (β = 0.65 (0.26, 1.04), P for trend = 0.001). For SAAC, after full adjustment, a one-unit increase in CMI resulted in a 35% elevated risk (OR = 1.35 (1.09, 1.67)). The significant association was also evident in quartile-based analyses, where participants in the highest CMI quartile showed an 114% heightened risk of SAAC than those in the reference quartile (OR = 2.14 (1.29, 3.54), P for trend = 0.005).

In Fig. 2, further analysis utilizing smoothed curve fitting identified a positive correlation of CMI with both AAC and SAAC.

Subgroup analysis

To determine whether the connections between CMI, AAC, and SAAC differ across various population subcategories, Subgroup analyses were carried out with stratification by sex, smoking status, diabetes, hypertension, CHF, angina pectoris, heart attack, CHD, and stroke. The results indicated significant variations in these associations across subgroups. The findings highlight significant interaction effects between AAC and sex, smoking status, and CHD (P for interaction < 0.05). For SAAC, significant interactions were identified with sex and smoking status (P for interaction < 0.05). Specifically, in the female subgroup, CMI had a stronger positive association with AAC and SAAC. In never smokers, this association was also more pronounced relative to current smokers. Additionally, among patients without CHF and those without a history of heart attack, the positive relationship between CMI and AAC was more significant. The results indicate that the influence of CMI on AAC and varies across demographic factors, including sex, smoking status, and cardiovascular conditions, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

Discussion

The purpose of this research was to examine, within a population-based sample, the association between CMI and AAC. Within the sample of 2704 participants, both a significant positive correlation between CMI and AAC and a significant trend across higher CMI strata were observed. Subgroup analyses indicated sex, smoking status, CHF, and history of heart attack modified this association. His study identifies a robust positive correlation between CMI and AAC, which warrants further investigation to determine if CMI management might have implications for AAC risk.

In 2015, Wakabayashi et al. initially introduced the CMI, as a predictive marker of diabetes and CVD risk17. According to Qiu et al., people with higher levels of CMI demonstrated a markedly higher propensity for early development of diabetes (HR = 1.78), while participants transitioning from lower to higher CMI ranges during the observation period exhibited a 75% increase in diabetes risk23. Luo et al. discovered that both CMI and CMI-age were independently linked to elevated CVD risk in a study involving 9,008 participants, highlighting the necessity of keeping an eye on people with high CMI16. Xu et al. performed a cohort study demonstrating a positive link between CMI and total mortality among older individuals, with inflammation playing a significant mediating role24. Among those suffering from concurrent obstructive sleep apnea and hypertension, Cai et al. conducted a positive correlation between CVD risk and CMI21. Similarly, Higashiyama et al. revealed that those without metabolic syndrome (MetS) but with greater CMI levels had an increased risk of ischemic CVD25. These findings underscore the strong association between CMI and various systemic diseases and its connection to poor prognosis. At present, no studies have evaluated the potential link between CMI and AAC, particularly in elderly persons who are more likely to have comorbidities.

Additional anthropometric and metabolic measures, including the triglyceride glucose (TyG) index, BRI, WWI, and VAI, have also been validated as associated with AAC or cardiovascular mortality. Chen et al. found that in a representative sample of American adults, the TyG index was meaningfully linked to extensive AAC (OR = 1.41), regardless of additional variables26. Chen et al. further elucidated a positive relationship between BRI and AAC (OR = 1.22)27. In their 20-year longitudinal study on BRI trends among American adults, Zhang et al. reported a U-shaped association with mortality risk, with increased risks observed at both ends of the BRI spectrum relative to median values28. According to Qin et al., WWI had a nonlinearly positive relationship with SAAC, and greater AAC scores were linked to higher WWI levels29. Greater VAI levels were linked to greater AAC (β = 0.04) and a higher chance of SAAC (OR = 1.04), according to Chen et al.30. Moreover, the research by Chen et al. found that elevated VAI levels were linked to a greater risk of composite cardiovascular events and overall death rates in a prospective research involving 464 common hemodialysis patients31. In line with earlier research on the cardiovascular implications of other obesity indicators, this study observed a positive relationship between CMI and AAC and found that CMI might be useful in cross-sectional assessments of AAC risk.

Elevated CMI, which reflects visceral obesity and metabolic abnormalities, is linked to Elevated triglyceride levels accompanied by reduced HDL cholesterol concentrations. These metabolic disturbances are key risk factors for atherosclerosis and vascular calcification32,33. Lipid-loaded vascular wall lesions are a hallmark of atherosclerosis. Chronic inflammation brought on by lipid buildup in the arterial wall activates the vascular endothelium and adhesion molecules are released in significant quantities, attracting circulating monocytes to the endothelium and promoting their maturation into macrophages. Macrophages that are laden with lipids then migrate into foam cells34. Foam cell apoptosis speeds up the establishment of a necrotic core and encourages the growth of lesions35. One of the main causes of atherosclerosis is the dysregulation of macrophage phenotypes. High-plasticity macrophages polarize to the pro-inflammatory M1 type and release a lot of inflammatory factors, including IL-6 and TNF-α, further activating immune cells within arterial walls, making plaques more prone to rupture and increasing the risk of cardiovascular events36,37,38,39. As atherosclerosis advances, the prolonged inflammatory environment and cell death within plaques promote vascular calcification40,41,42,43. Vascular calcification is fundamentally characterized by the transdifferentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) from a mesenchymal lineage into osteoblast-like cells, constituting a central pathological mechanism44. The presence of arterial calcific plaques induces biomechanical stress through compromised vascular compliance, resulting in sustained mechanical strain that promotes both proliferative and osteogenic differentiation of VSMCs45. Transcriptomic analyses reveal partial activation of osteogenic transcriptional programs in phenotypically modulated VSMCs, though the magnitude of osteoblast-specific mRNA expression remains markedly reduced compared to terminally differentiated osteoblasts46. Pathological elevations in extracellular calcium-phosphate concentrations synergistically potentiate vascular mineralization through dual mechanisms: direct physicochemical precipitation and induction of VSMC phenotypic reprogramming via upregulation of osteogenic differentiation-associated proteins47,48. This calcification cascade is primarily mediated by the canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling cascade, with RUNX2 emerging as the principal transcriptional regulator orchestrating VSMC osteochondrogenic transformation, osteoblastic differentiation, and subsequent initiation of ectopic mineralization processes49,50. These processes work together to drive calcification, inflammation, and stress from oxidation in the arterial intima.51,52.

This research is affected by several limitations. The primary limitation is that the cross-sectional design employed in this analysis precludes causal inferences between CMI and AAC. Therefore, future prospective research is necessary to validate these results. Second, because of restrictions within the NHANES database, not all relevant covariates that may affect BRI and AAC were included. These excluded variables may have predictive value and merit further investigation. Third, AAC-related data are only available in the 2013–2014 NHANES cycle, which restricts the sample size and may limit the generalizability of our results. Lastly, NHANES data are representative of the U.S. population and include only individuals aged 40 and older (due to AAC measurement constraints). To confirm the broader applicability of these findings, additional research should focus on diverse countries and younger populations.

Conclusion

In this cross-sectional NHANES study, Our results indicate a significant positive relationship between CMI and AAC, highlighting the potential of CMI as a screening indicator to detect individuals with a higher risk for vascular calcification, particularly in populations with metabolic risk factors. Future research should focus on investigating the impact of CMI management on AAC and related cardiovascular risks, providing valuable insights for clinical and public health strategies.

Data availability

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey dataset at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/.

Abbreviations

- AAC:

-

Abdominal aortic calcification

- SAAC:

-

Severe abdominal aortic calcification

- CMI:

-

Cardiometabolic index

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- CAC:

-

Coronary artery calcification

- CHD:

-

Coronary heart disease

- WHtR:

-

Waist-to-height ratio

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- HDL:

-

High-density lipoprotein

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- PIR:

-

Poverty-to-income ratio

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CHF:

-

Congestive heart failure

References

Bardeesi, A. S. et al. A novel role of cellular interactions in vascular calcification. J. Transl. Med. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-017-1190-z (2017).

Sethi, A. et al. Calcification of the abdominal aorta is an under-appreciated cardiovascular disease risk factor in the general population. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 1003246. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.1003246 (2022).

Tesche, C. et al. Correlation and predictive value of aortic root calcification markers with coronary artery calcification and obstructive coronary artery disease. Radiol. Med. 122, 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11547-016-0707-5 (2017).

Reaven, P. D., Sacks, J., Investigators for the Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study of Glycemic Control and Complications in Diabetes Mellitus Type 2. Reduced coronary artery and abdominal aortic calcification in hispanics with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 27, 1115–1120. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.27.5.1115 (2004).

Wilson, P. W. F. et al. Abdominal aortic calcific deposits are an important predictor of vascular morbidity and mortality. Circulation https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.103.11.1529 (2001).

Schousboe, J. T. et al. Abdominal aortic calcification (AAC) and ankle-brachial index (ABI) predict health care costs and utilization in older men, independent of prevalent clinical cardiovascular disease and each other. Atherosclerosis 295, 31–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2020.01.012 (2020).

Gonçalves, F. B. et al. Calcification of the abdominal aorta as an independent predictor of cardiovascular events: A meta-analysis. Heart 98, 988–994. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2011-301464 (2012).

Criqui, M. H. et al. Abdominal aortic calcium, coronary artery calcium, and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 34, 1574–1579. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303268 (2014).

Liu, Q. et al. Associations between life’s essential 8 and abdominal aortic calcification among US adults: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 24, 1090. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18622-7 (2024).

González-Muniesa, P. et al. Obesity. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 3, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2017.34 (2017).

Tomiyama, A. J. Stress and obesity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 70, 703–718. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102936 (2019).

Vekic, J., Stefanovic, A. & Zeljkovic, A. Obesity and dyslipidemia: A review of current evidence. Curr. Obes. Rep. 12, 207–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-023-00518-z (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. Association between visceral adiposity index and heart failure: A cross-sectional study. Clin. Cardiol. 46, 310–319. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.23976 (2023).

Aryee, E. K., Ozkan, B. & Ndumele, C. E. Heart failure and obesity: The latest pandemic. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 78, 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2023.05.003 (2023).

Scicchitano, P. & Massari, F. The role of bioelectrical phase angle in patients with heart failure. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 24, 465–477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-022-09757-2 (2023).

Luo, X. & Cai, B. Association between cardiometabolic index and congestive heart failure among US adults: A cross-sectional study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 11, 1433950. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2024.1433950 (2024).

Wakabayashi, I. & Daimon, T. The, “cardiometabolic index” as a new marker determined by adiposity and blood lipids for discrimination of diabetes mellitus. Clin. Chim. Acta 438, 274–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2014.08.042 (2015).

Guo, Q. et al. Association between the cardiometabolic index and chronic kidney disease: A cross-sectional study. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 56, 1733–1741. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-023-03888-4 (2024).

Li, F.-E. et al. Association between cardiometabolic index and stroke: A population-based cross-sectional study. Curr. Neurovasc. Res. 18, 324–332. https://doi.org/10.2174/1567202618666211013123557 (2021).

Zuo, Y.-Q., Gao, Z.-H., Yin, Y.-L., Yang, X. & Feng, P.-Y. Association between the cardiometabolic index and hyperuricemia in an asymptomatic population with normal body mass index. Int. J. Gen. Med. 14, 8603–8610. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S340595 (2021).

Cai, X. et al. Associations of the cardiometabolic index with the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea: Results of a longitudinal cohort study. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 4914791. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/4914791 (2022).

Liu, Y. & Wang, W. Sex-specific contribution of lipid accumulation product and cardiometabolic index in the identification of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease among Chinese adults. Lipids Health Dis. 21, 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-021-01617-3 (2022).

Qiu, Y. et al. Transition of cardiometabolic status and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus among middle-aged and older Chinese: A national cohort study. J. Diabetes Investig. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdi.13805 (2022).

Xu, B. et al. Is systemic inflammation a missing link between cardiometabolic index with mortality? Evidence from a large population-based study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 23, 212. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-024-02251-w (2024).

Higashiyama, A. et al. The risk of fasting triglycerides and its related indices for ischemic cardiovascular diseases in Japanese community dwellers: The Suita study. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 28, 1275–1288. https://doi.org/10.5551/jat.62730 (2021).

Chen, Y. et al. Association between the triglyceride-glucose index and abdominal aortic calcification in adults: A cross-sectional study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 31, 2068–2076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2021.04.010 (2021).

Wu, J., Lu, D. & Chen, X. Association of body roundness index with abdominal aortic calcification among middle aged and elderly population: Findings from NHANES. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 11, 1475579. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2024.1475579 (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. Body roundness index and all-cause mortality among US adults. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e2415051. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.15051 (2024).

Qin, Z. et al. The association between weight-adjusted-waist index and abdominal aortic calcification in adults aged ≥ 40 years: Results from NHANES 2013–2014. Sci. Rep. 12, 20354. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-24756-8 (2022).

Qin, Z. et al. Higher visceral adiposity index is associated with increased likelihood of abdominal aortic calcification. Clinics https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinsp.2022.100114 (2022).

Chen, H.-Y. et al. Visceral adiposity index and risks of cardiovascular events and mortality in prevalent hemodialysis patients. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 13, 136. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-014-0136-5 (2014).

Krauss, R. M. Lipids and lipoproteins in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 27, 1496–1504. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.27.6.1496 (2004).

Ginsberg, H. N. & MacCallum, P. R. The obesity, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes mellitus pandemic: part I. Increased cardiovascular disease risk and the importance of atherogenic dyslipidemia in persons with the metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Cardiometab. Syndr. 4, 113–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-4572.2008.00044.x (2009).

Diao, Y. & Clematichinenoside, A. R. Alleviates foam cell formation and the inflammatory response in Ox-LDL-induced RAW264.7 cells by activating autophagy. Inflammation 44, 758–768. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10753-020-01375-x (2021).

Wei, X. et al. Phoenixin-20 prevents ox-LDL-induced attachment of monocytes to human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs): A protective implication in atherosclerosis. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 12, 990–997. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00787 (2021).

Hutcheson, J. D., Blaser, M. C. & Aikawa, E. Giving calcification its due: Recognition of a diverse disease—A first attempt to standardize the field. Circ. Res. 120, 270–273. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.310060 (2017).

Kuznetsova, T., Prange, K. H. M., Glass, C. K. & De Winther, M. P. J. Transcriptional and epigenetic regulation of macrophages in atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 17, 216–228. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-019-0265-3 (2020).

Guerrero, F. et al. TGF-β prevents phosphate-induced osteogenesis through inhibition of BMP and Wnt/β-catenin pathways. PLoS ONE 9, e89179. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089179 (2014).

Hao, N. et al. Interleukin-29 accelerates vascular calcification via JAK2/STAT3/BMP2 signaling. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 12, e027222. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.122.027222 (2023).

Xie, R., Liu, X., Wu, H., Liu, M. & Zhang, Y. Associations between systemic immune-inflammation index and abdominal aortic calcification: Results of a nationwide survey. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 33, 1437–1443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2023.04.015 (2023).

Bagyura, Z. et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is an independent risk factor for coronary artery disease in central obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24087397 (2023).

Sánchez-Cabo, F. et al. Subclinical atherosclerosis and accelerated epigenetic age mediated by inflammation: A multi-omics study. Eur. Heart J. 44, 2698–2709. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad361 (2023).

Li, M. et al. Programmed cell death in atherosclerosis and vascular calcification. Cell Death Dis. 13, 467. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-022-04923-5 (2022).

Donoghue, P. S., Sun, T., Gadegaard, N., Riehle, M. O. & Barnett, S. C. Development of a novel 3D culture system for screening features of a complex implantable device for CNS repair. Mol. Pharm. 11, 2143–2150. https://doi.org/10.1021/mp400526n (2014).

Tang, X. et al. Pathological cyclic strain promotes proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells via the ACTH/ERK/STAT3 pathway. J. Cell Biochem. 119, 8260–8270. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.26839 (2018).

Patel, J. J. et al. Differing calcification processes in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells and osteoblasts. Exp. Cell Res. 380, 100–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yexcr.2019.04.020 (2019).

Persy, V. & D’Haese, P. Vascular calcification and bone disease: the calcification paradox. Trends Mol. Med. 15, 405–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmed.2009.07.001 (2009).

Campbell, G. R. & Campbell, J. H. Smooth muscle phenotypic changes in arterial wall homeostasis: Implications for the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 42, 139–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-4800(85)90023-1 (1985).

Lin, M.-E., Chen, T., Leaf, E. M., Speer, M. Y. & Giachelli, C. M. Runx2 expression in smooth muscle cells is required for arterial medial calcification in mice. Am. J. Pathol. 185, 1958–1969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.03.020 (2015).

Saidak, Z. et al. Wnt/β-catenin signaling mediates osteoblast differentiation triggered by peptide-induced α5β1 integrin priming in mesenchymal skeletal cells. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 6903–6912. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M114.621219 (2015).

Dini, C. S. et al. Contemporary approach to heavily calcified coronary lesions. Interv. Cardiol. https://doi.org/10.15420/icr.2019.19.R1 (2019).

Sage, A. P., Tintut, Y. & Demer, L. L. Regulatory mechanisms in vascular calcification. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 7, 528–536. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2010.115 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Funding

There is no funding in this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Minjiang Ren: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing—Original draft preparation; Yifan Shen: Conceptualization, Writing—Original draft preparation; Ye Yuan: Conceptualization, Methodology; Zhiyu Han: Conceptualization, Data curation; Yun Zhong: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing—review & editing; Shiming Liu: Conceptualization, Supervision; Writing—review & editing; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The NCHS ethics review board approved the NHANES protocol. And each participant authorized the informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ren, M., Shen, Y., Yuan, Y. et al. Association between cardiometabolic index and abdominal aortic calcification in US adults from the NHANES. Sci Rep 15, 17831 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01848-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01848-9