Abstract

To reveal morphological changes in musculoskeletal apparatus after conservative treatment of condylar head fracture (CHF) by clinical examinations, condylar and masticatory muscle reconstruction, to guide the clinical therapeutic strategy. Patients with unilateral CHF and treated conservatively during November 2015 to January 2020 were enrolled and followed up for 2 years. Clinical assessments (mouth open, mandible deviation and occlusal relationship), and CT reconstruction (condyle, ramus height, masseter and lateral pterygoid) immediately and 2 years after fracture were compared with the unfractured side as control group. Mixed-effect analysis and two-way ANOVA were manipulated and P ≤ 0.05 was defined as significant. 26 patients were involved. The average of maximum mouth opening increased from 12.6 ± 5.40 mm to 27.8 ± 8.60 mm. Significant musculoskeletal resorption with an average condyle volume decrease of 241.86 mm3 (P = 0.0029), ramus height decrease of 1.87 mm (P = 0.0004), masseter volume decrease of 3,447.3 mm3 (P < 0.0001), and lateral pterygoid volume decrease of 1203.05 mm3 (P = 0.0049) occurred. No significant changes occurred to the unfractured sides. Conservative treatment of CHF displayed significant musculoskeletal resorption. Clinical assessments showed less optimal improvements. Surgeons should be aware of these trends and take full consideration before applying nonsurgical treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Condylar fractures, including condylar head, neck, and base fractures, may be caused by a direct trauma or indirect forces transmitted from a blow elsewhere in the mandible bone1, accounting for about 29–52% of the mandible fracture2. Complications include masticatory function disturbance, mandible deviation, disc displacement and ankylosis3. Not only the bone but also the intra-articular soft tissues are severely injured in condylar dislocations, and the posterior ligament is often torn4. Since the condyle serves an important role in appearance, speech, swallowing and respiration, injury to the condylar region deserves special care5.

The treatment aims at pain alleviation, re-establishment of occlusal relationship, improvement on facial symmetry, mouth opening greater than 35 mm and unrestricted lateral and protrusive movements6. For decades, conservative treatment has been the preferred treatment because treatment is easier and less invasive, and the results are comparable, with no surgical complications7. The conservative management of condylar fractures usually applies to patients with intracapsular fractures without open mouth restriction, loss of the ramus height or malocclusion6, avoiding surgical complications such as damage to the facial nerve, scarring or wound infections, and comprises varying periods of intermaxillary fixation (0 to 6 weeks).

Existing studies8,9,10,11 focused mostly on the follow-up of clinical symptoms, and found that conservative treatment might alleviate complications, while showing less effective in restoring the ramus height. Wu et al. found worse condyle reconstruction in conservative treatment than open reduction12. Zhou et al. further declared that condyle resorption and serious shortening of the ascending ramus usually occurred in the displaced direction in conservative treatment for condylar fractures13. Al-Moraissi et al. also pointed out that conservative treatment might exhibit less optimal outcome than open reduction and rigid fixation. However, quantitative and statistical analysis of the musculoskeletal modification for nonsurgical treatment among condylar head fractures was rare and lack of evidence base. This study conducted a 2 year follow up self-controlled study of unilateral mandibular condylar head fractures and treated conservatively in the Oral and Maxillofacial Department with an aim to quantitatively evaluate the morphological changes in the musculoskeletal apparatus based on clinical follow-up, radiological reconstruction, and statistical analysis.

Materials and methods

Selection of clinical cases

This self-controlled experimental study enrolled patients’ data selected from those who were admitted to the department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital with unilateral condylar head fracture between November 2015 to January 2020. The letter of informed consent was signed before the proceeding of treatment, clarifying all medical and imaging documents were approved for experimental study or article publication without the revelation of personal privacy under the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Inclusion criteria

-

a.

Adult patients diagnosed with unilateral condylar head fracture without other maxillofacial fractures and treated conservatively.

-

b.

Unilateral condylar head fracture (CHF) including CHF location (M/P), fragmentation (0/1/2), and vertical apposition (0/1/2) according to Neff’s classification14.

-

c.

Cases with complete clinical follow-up and Computed Tomography (CT) obtained after trauma and at the end of the postoperative second year.

-

d.

CT scans and temporomandibular joint magnetic resonance imaging (TMJ-MRI) with high quality.

Exclusion criteria

-

a.

Patients with severe developmental disorders, mandible bone pathology or tumors.

-

b.

Patients with osteoporosis using bisphosphonates or other antiresorptive medications which interfere with bone metabolism.

-

c.

Patients with no molars or edentulous, and those who were allergic to titanium, which influenced the manipulation of conservative treatment.

-

d.

Patients lost to the follow-up or lack of clinical and imaging records.

Description of Conservative treatment

The treatment protocol has been reported in our previous study in detail15. Patients wore maxillary splint with soft pads on the molars of the affected sides, thus creating a fulcrum. Self-drilling mini screws were inserted into anterior alveolar bone. Vertical traction was applied by elastics (ORMCO, 3/16, 8oz), approximately 500–600 g/side, for more than 22 h per day. Traction elastics and the splint could be removed shortly to facilitate food taking and oral hygiene. Daily physical exercises started 1 month after fracture, in which patients use their thumb and index finger to manually expand the MIO, and those exercises should be insisted for at least 5 times per day, and 5 min duration for each time. The above semi-rigid intermaxillary ligation continued at night, but gradually reduced.

Clinical follow-up

The intervals for follow-up were 1 week after the manipulation of conservative treatment, and then 1 month, 3 months, half a year, and 1 year, 2 years, 5 years. Since the covid-19 exploded and hindered patients from a regular follow-up, online video calls were used in certain cases and CT and TMJ-MRI were requested every half a year for a minimum frequency. Data were collected and reconstructed immediately after fracture and at least 2 years after treatment for statistical analysis.

Maximum interincisal mouth opening, mandible deviation and occlusal relationship were measured and compared immediately and 2 years after fracture. The maximum interincisal mouth opening was calculated by the distance from the medial corner of the upper incisor to the medial corner of the lower incisor16,17. The mandible deviation was defined by the distance between the pogonion to the midsagittal plane18, and a deviation of the pogonion over 3 mm from the midline was defined as mandible deviation19. The malocclusion caused by condylar fracture, such as the open bite of the posterior teeth and cross bite of the opposite side, or the open bite of the anterior teeth were documented20.

Evaluation of disc-condyle relationship

According to De Stefano, A.A21, in the maximum intercuspation position (ICP), the border between the low signal of the disc and the high signal of the retrodiscal tissue was located between the 11:30 and 12:30 clock positions and the intermediate zone was located between the anterior-superior aspect of the condyle and the posterior-inferior aspect of the articular eminence, which was defined as a normal disc-condyle relationship. If the low signal of the disc and the high signal of the retrodiscal tissue were located anterior to the 11:30 clock position both in maximum intercuspation and full open-mouth position, then an anterior displacement occurred.

3D reconstruction of the musculoskeletal structure

Reconstruction of the condyle

Spiral CT was produced by GE (USA) with tube voltage of 80–140 kV, tube current of 50–500 mA, exposure time of 0.3–1.0 s, and advanced imaging technologies for high-resolution diagnostics.

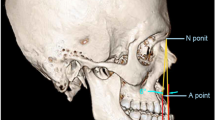

To quantify the changes of condylar volume, CT reconstruction before and 2 years after treatment was compared and analyzed. Mimics Research 21.0 (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium) was used for reconstruction. The Frankfort Horizontal plane (FH plane) was defined by the left intraorbital point and 2 auricular points, the other planes were formed through the lowest points of the sigmoid notch, parallel to the FH plane. The “Measure and Analyze” function was used to personally input the reference points and planes, and “With Polyplanes” and “Splint” function were then utilized to cut and separate the condyle, then the condyle volume counted by pixels directly appeared alongside by the software with a unit of mm3. As shown in Fig. 1, The left and right condyles were separated by the sigmoid notch plane, and the upper border was the outline of the condyle. The volume of the condyles were calculated based on the number of the pixel.

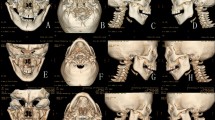

Reconstruction of the masticatory muscle and the ramus height

CT were transformed into DICOM format and imported into Mimics Research 21.0 (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium). Threshold of soft tissue (−700 ~ 225 HU) was chosen, and the contour of masticatory muscle was depicted by Lasso in each layer and interpolated, as shown in Fig. 2A, B.

The extent of the mandible ramus was defined by the vertical distance between the gonial angle.

point (Go) and the plane through the condylar top point parallel to the FH plane22. The condylar top point and Go point were set manually on each reconstructed mandible as described in Fig. 2C, and the distance was calculated automatically after setting the points.

To validate the reproducibility of the reconstruction, all measurements were repeated by the same investigator (Bu L) twice, and the average distance or volume were adopted.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was accomplished by GraghPad Prism (Version 9.0.0, GraghPad Software, LLC, San Diego, California, USA). The volume of the condyle, the masseter, the lateral pterygoid, and the ramus height immediately and 2 years after CHF were compared. Shapiro-Wilk test was used to verify Gaussian distribution. For condylar volume, Mixed-effects model (REML) was applied for comparison, while for ramus height, masseter and lateral pterygoid muscle volume, Two-way RM ANOVA was applied for comparison. The differences were considered statistically significant at *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, ****p ≤ 0.0001.

Results

Patients’ data

26 patients were included in the study based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. There were 16 males and 10 females (with a male : female ratio of 8:5). Their mean age was 36 years (range, 7 to 60 years). The condylar fracture was caused by falling in 20 patients, external force in 4 and traffic accident in 2. All patients underwent conservative treatment. (Table 1)

Clinical assessment and complications

The average of maximum mouth opening increased from 12.6 ± 5.40 mm to 27.8 ± 8.60 mm 2 years after fracture. Mandible deviation occurred to 16.64% of patients immediately after fracture and decreased to 10.53% 2 years later. Abnormal occlusal relationships were complained by 85.42% patients, and improved during 2 years re-establishment.

1 patient diagnosed by unilateral condylar head fracture and treated conservatively suffered from artificial joint replacement on the left side 2 years later.

The disc-condyle relationship

Evaluated by TMJ-MRI, 25 patients exhibited a relatively normal disc-condyle relationship with normal disc contour immediately after fracture. The fractured fragment moved inward medially. In the maximum intercuspation position, the border between the low signal of the disc and the high signal of the retrodiscal tissue was still located between the 11:30 and 12:30 clock positions and the intermediate zone was located between the anterior-superior aspect of the condyle and the posterior-inferior aspect of the articular eminence.

In the full open-mouth position, since the maximum mouth opening remained only 12.2 ± 6.7 mm immediately after fracture, the intermediate zone of the disc was still between the articular eminence and the condyle articular surface. 2 years after conservative treatment, the TMJ-MRI showed reconstruction of the condyle bone, and the disc-condyle relationship remained as shown in Fig. 3.

Typical TMJ-MRI findings postoperatively and 2 years later in patients with condylar head fractures. (A) Immediately after fracture, the intermediate zone of the disc was between the articular eminence and the condyle articular surface in maximum intercuspation. Articular fluid is visible in the upper cavity. (B) Immediately after fracture, the intermediate zone of the disc was between the articular eminence and the condyle articular surface in open position. Articular fluid is visible in the upper and lower cavities. (C) Coronal section showed medial displaced segment and articular fluid. (D) 2 years after fracture, the border between the low signal of the disc and the high signal of the retrodiscal tissue located between the 11:30 to 12:30 clock positions in maximum intercuspation position. (E) The intermediate zone was located between the anterior-superior aspect of the condyle and the posterior-inferior aspect of the articular eminence in full open-mouth position. Articular fluid disappeared. (F) Coronal section showed fusion of displaced segment. (yellow: condyle cancellous bone; brown: condyle cortical bone; dark red: condylar disc; blue: joint fluid).

One patient showed an acute anterior disc dislocation immediately after fracture with no rapture initially, both in closed-mouth and open-mouth position, as shown in Fig. 4. The initial MIO was 2 cm. The fracture fragment was too tiny to be fixed, and the patient refused to reposition the disc. 2 years later, the disc remained anteriorly dislocated and rapture occurred, the cortical bone of the condyle showed irregular contour, which indicated the formation of osteoarthritis. The MIO increased slightly to 2.5 cm 2 years after conservative treatment, and the pogonion showed a 1.4 mm deviation to the left side.

Anterior dislocation of disc after condylar fracture and the formation of osteoarthritis 2 years later. (A, B,C) Immediately after fracture, the low signal of the disc and the high signal of the retrodiscal tissue are located anterior to the 11:30 clock position both in maximum intercuspation and full open-mouth position. (D, E,F) 2 years after fracture, the disc shrink, and the anterior dislocation remained, the contour of the cortical bone of the condyle showed irregular. (yellow: condyle cancellous bone; brown: condyle cortical bone; dark red: condylar disc).

Reconstruction of the condyle, the masticatory muscle, and the ramus height

Condylar volume analysis

Mixed-effect analysis proved a significant condylar volume decrease from an average of 2119.05 ± 458.2 mm3 to 1846.5 ± 404.6 mm3 (P = 0.0029) on the fracture side, while no significant change on the unfractured side observed. CHF-M exhibited a significant average decrease of 292.82 mm3 (P = 0.0010), while for CHF-P, an average decrease of 217 mm3 was found without significance (Figs. 5A and 6A).

Ramus height

The ramus height decreased significantly from an average of 50.34 ± 10.33 mm to 48.50 ± 9.85 mm (P = 0.0004) on the fracture side, while no significant change on the unfractured side observed. CHF-M displayed a significant average decrease of 1.81 mm (P = 0.0017), while for CHF-P, an average decrease of 1.1 mm was found without significance (Figs. 5B and 6B).

Masseter volume analysis

The masseter volume decreased significantly from an average of 23992.6 ± 9241 mm3 to 20545.3 ± 8362 mm3 (P < 0.0001) on the fracture side, while no significant change on the unfractured side observed. CHF-M displayed a significant average decrease of 3,786.6 mm3 (P < 0.0001), while for CHF-P, an average decrease of 2,542.7 mm3 was found without significance (Figs. 5C and 6C).

Lateral pterygoid volume analysis

The lateral pterygoid volume decreased significantly from an average of 8180.28 ± 2470 mm3 to 6977.23 ± 2397 mm3 (P = 0.0049) on the fracture side, while no significant change on the unfractured side observed. CHF-M showed a significant average decrease of 1,407.75 mm3 (P = 0.0007), while for CHF-P, an average decrease of 657.2 mm3 was found without significance (Figs. 5D and 6D).

Self-controlled comparison of the musculoskeletal modification between the fractured and unfractured side. (A) Modification of condylar volume in CHF (fractured versus unfractured). (B) Modification of ramus height in CHF (fractured versus unfractured). (C) Modification of masseter volume in CHF (fractured versus unfractured). (D) Modification of lateral pterygoid volume in CHF (fractured versus unfractured).

Discussion

In this study, 26 patients with unilateral condylar head fractures were treated conservatively, and the morphological modification of musculoskeletal apparatus were reconstructed and statistically analyzed, to guide the therapeutic strategy. The clinical outcome of conservative treatment after condylar fracture was less than ideal, which agreed to the study of Hisham S. et al., who found midline deviations persisted without significant alterations after functional orthodontic treatment of mandibular condyle fractures23. The condylar fracture fragment moved inward, interfering with the movement of the mandible bone, thus leading to mouth opening limitation. As the height of the mandible ramus shortened due to fracture, unilateral condylar fracture might cause the chin to incline to the fractured side, or backward in the condition of bi-lateral condylar fracture. Even though Qi J. believed that both adolescent and adult condyle had a strong remodeling ability no matter the manipulations24, on the contrary, we found the reconstruction potency of the condyle was less than enough to support an ideal recovery of maximum mouth opening and mandible deviation even after adequate physical exercise.

There was a noticeable trend that CHF exhibited significant musculoskeletal resorption after conservative treatment, which was a new finding never been reported. The tremendous bone resorption after conservative treatment of mandibular condylar fracture found in this study was also supported by many others. Wu S. et al. found that the condylar reconstruction in the surgical group was better than that in conservative treatment, in which the growth of condylar process was poor, and the condylar shape and position were not as good as surgical repositioning, which agreed to our previous (under publication) and this study12. Moreover, Aleš V. et al. also proved that surgical treatment restored anatomy and securely enabled further symmetric growth of the condyles, mandible, and the entire facial skeleton25. Yang R. et al. revealed the process of ramus height resorption that conservative treatment failed in promoting the spontaneous fracture reduction in patients with CHF, and the absorption of the lateral process of the condyle became close to the ‘horizontal absorption’, until the height of the lateral condylar process dropped and aligned to the articular surface of the medial process26. Besides CHF, Zhou H. et al. found that conservative treatment could hardly restore the ramus height of extracapsular condylar fractures, however, surgical treatment of ORIF can substantially restore the ramus height for dislocated fractures27. There remains one topic which needs to be emphasized and studied on in the future. Since existing studies possessed different ways of separating the condyle, which reminded a lack of a uniform way of mandibular condylar reconstruction to minimize the bias in clinical trials.

Soft tissue is gaining more and more attention these days, as far as this study group was concerned, there existed few condylar fracture research concerning the change of masticatory muscle. This study revealed a significant resorption of the masseter and the lateral pterygoid in CHF after conservative treatment. The mechanism behind might be explained by Loreine M. et al., who further revealed the side effect of the shortening of the ramus height after condylar fracture by finite element analysis that the loading capacity of the fractured condyle descended, leading to dysfunction of the masticatory system28. Based on the self-controlled analysis, the unfractured sides were barely affected by the CHF, which was a result within expectation. In future studies, the morphological modification of the medial pterygoid and the temporalis will be studied on. Moreover, the significant drop of masticatory muscles volume might be due to the initial edema immediately after trauma when the first CT was acquired, in future studies, improved reconstruction on the muscle should be worked on.

Özlem A. found a progressive tendency of disc displacement after condylar fracture managed by conservative treatment that not only no disc displacement recovered but more disc displacement occurred during the follow up, and emphasized the early diagnosis of disc displacement by TMJ-MRI and early reduction29. Ruptured or displaced discs might cause pain, dysfunction, or osteoarthritis in advanced stages. Ying et al. stressed that the disc and the condyle must be managed as a whole unit30, which agreed to this study. Thus, before conducting conservative treatment, assuring a correct disc-condyle relationship is important to prevent osteoarthritis.

In our point of view, choice of conservative treatment should be carefully depended on the level and displacement of the fracture, the state of dentition and dental occlusion, and the aesthetical and functional aspects31. For CHF, manipulation of open reduction was difficult due to the tiny size or medial dislocation of the fracture fragments in certain cases. Plus, patients’ age had a crucial role in the treatment choice, and the type of fracture (presence of condylar displacement, or dislocation) was also a major prognostic indicator of the radiologic outcome. Even though a limitation of case numbers and investigators existed in this study, we hope this study raises more attention on the reconstruction of soft tissue in the field of oral and maxillofacial surgery and gives insight into the sequelae of non-surgical treatment of mandibular condyle fractures. Moreover, surgeons should be aware of these trends before conservative treatment and understand the changes that occur after such treatment.

Conclusion

Less than ideal functional results could be achieved by conservative treatment. Bone resorption and masticatory muscle atrophy happened to the musculoskeletal apparatus after conservative treatment in cases of unilateral condylar head fracture, especially in CHF cases with medial displaced segment. Surgeons should strictly control the indication of conservative treatment in condylar head fractures and be aware of the negative outcome.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

References

Karagah, A. et al. Correlation of radiomorphometric indices of the mandible and mandibular angle fractures. Heliyon 8 (9), e10549 (2022).

Krishnan, S., Periasamy, S. & Arun, M. Evaluation of patterns in mandibular fractures among South Indian patients. Bioinformation 18 (6), 566–571 (2022).

Nys, M., Van Cleemput, T., Dormaar, J. T. & Politis, C. Long-term complications of isolated and combined condylar fractures: A retrospective study. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma. Reconstruction. 15 (3), 246–252 (2022).

Akkoc, M. F. & Bulbuloglu, S. The treatment perspective of pediatric condyle fractures and Long-Term outcomes. Cureus 14 (10), e30111 (2022).

Patel, H. B., Desai, N. N., Matariya, R. G., Makwana, K. G. & Movaniya, P. N. Unilateral condylar fracture with review of treatment modalities in 30 Cases - An evaluative study. Annals Maxillofacial Surg. 11 (1), 37–41 (2021).

Menon, S., Kumar, V., Archana, S., Nath, P. & Shivakotee, S. A retrospective study of condylar fracture management in a tertiary care Hospital-A 10-Year experience. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 19 (3), 380–386 (2020).

Al-Moraissi, E. A. & Ellis, E. 3 Surgical treatment of adult mandibular condylar fractures provides better outcomes than closed treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Oral Maxillofacial Surgery: Official J. Am. Association Oral Maxillofacial Surg. 73 (3), 482–493 (2015).

Throckmorton, G. S. & Ellis, E. 3 Recovery of mandibular motion after closed and open treatment of unilateral mandibular condylar process fractures. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 29 (6), 421–427 (2000).

Ishihama, K. et al. Comparison of surgical and nonsurgical treatment of bilateral condylar fractures based on maximal mouth opening. Cranio: J. Craniomandib. Pract. 25 (1), 16–22 (2007).

Merlet, F. L. et al. Outcomes of functional treatment versus open reduction and internal fixation of condylar mandibular fracture with articular impact: A retrospective study of 83 adults. J. Stomatology Oral Maxillofacial Surg. 119 (1), 8–15 (2018).

Kolk, A. et al. Prognostic factors for long-term results after condylar head fractures: A comparative study of non-surgical treatment versus open reduction and osteosynthesis. J. cranio-maxillo-facial Surgery: Official Publication Eur. Association Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Surg. 48 (12), 1138–1145 (2020).

Shiyan, W., Shi, J. & Zhang, W. Effect of different treatment modalities for condylar fractures in childhood on mandibular symmetry and temporomandibular joint function: A retrospective study. J. Craniofac. Surg. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0000000000010237 (2024).

Zhou, H. H., Lv, K., Yang, R. T., Li, Z. & Li, Z. B. Extracapsular condylar fractures treated conservatively in children: mechanism of bone remodelling. J. Craniofac. Surg. 32 (4), 1440–1444 (2021).

Neff, A., Cornelius, C. P., Rasse, M., Torre, D. D. & Audigé, L. The comprehensive AOCMF classification system: condylar process Fractures - Level 3 tutorial. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma. Reconstruction. 7 (Suppl 1), S044–058 (2014).

Ren, R., Dai, J., Zhi, Y., Xie, F. & Shi, J. Comparison of temporomandibular joint function and morphology after surgical and non-surgical treatment in adult condylar head fractures. J. cranio-maxillo-facial Surgery: Official Publication Eur. Association Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Surg. 48 (3), 323–330 (2020).

AlHammad, Z. A., Alomar, A. F., Alshammeri, T. A. & Qadoumi, M. A. Maximum mouth opening and its correlation with gender, age, height, weight, body mass index, and temporomandibular joint disorders in a Saudi population. Cranio: J. Craniomandib. Pract. 39 (4), 303–309 (2021).

Aliya, S., Kaur, H., Garg, N. & Rishika, Yeluri, R. Clinical measurement of maximum mouth opening in children aged 6–12. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 45 (3), 216–220 (2021).

Economou, S. et al. Evaluation of facial asymmetry in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: correlation between hard tissue and soft tissue landmarks. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthopedics: Official Publication Am. Association Orthodontists its Constituent Soc. Am. Board. Orthod. 153 (5), 662–672e661 (2018).

Oh, M. H. & Cho, J. H. The three-dimensional morphology of mandible and glenoid fossa as contributing factors to menton deviation in facial asymmetry-retrospective study. Prog. Orthodont. 21 (1), 33 (2020).

Mooney, S., Gulati, R. D., Yusupov, S. & Butts, S. C. Mandibular condylar fractures. Facial Plast. Surg. Clin. North Am. 30 (1), 85–98 (2022).

De Stefano, A. A., Guercio-Monaco, E., Hernández-Andara, A. & Galluccio, G. Association between temporomandibular joint disc position evaluated by magnetic resonance imaging and mandibular condyle inclination evaluated by computed tomography. J. Rehabil. 47 (6), 743–749 (2020).

van Bakelen, N. B., van der Graaf, J. W., Kraeima, J. & Spijkervet, F. K. L. Reproducibility of 2D and 3D Ramus height measurements in facial asymmetry. J. Personalized Med. 12(7), 1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12071181 (2022).

Sabbagh, H., Nikolova, T., Kakoschke, S. C., Wichelhaus, A. & Kakoschke, T. K. Functional orthodontic treatment of mandibular condyle fractures in children and adolescent patients: an MRI Follow-Up. Life (Basel Switzerland) 12(10), 1596. https://doi.org/10.3390/life12101596 (2022).

Qi, J., Deng, Y., Jiang, L., Lu, Y. & Li, W. Conservative versus surgical approaches in the treatment of intracapsular condylar fractures: A retrospective study. Facial Plast. Surgery: FPS. 40 (6), 784–788 (2024).

Vesnaver, A. Dislocated pediatric condyle fractures - should Conservative treatment always be the rule? J. cranio-maxillo-facial Surgery: Official Publication Eur. Association Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Surg. 48 (10), 933–941 (2020).

Yang, R. C. et al. Fracture fragment of the condyle determines the Ramus height of the mandible in children with intracapsular condylar fractures treated conservatively. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 19924 (2022).

Zhou, H. H., Lv, K., Yang, R. T., Li, Z. & Li, Z. B. Restoration of Ramus height in child patients with extracapsular condylar fractures: is this mission almost impossible to accomplish?? J. Craniofac. Surg. 32 (3), e293–e296 (2021).

Helmer, L. M. L. et al. Load distribution after unilateral condylar fracture with shortening of the Ramus: a finite element model study. Head Face Med. 19 (1), 27 (2023).

Akkemik, Ö., Kugel, H. & Fischbach, R. Acute soft tissue injury to the temporomandibular joint and posttraumatic assessment after mandibular condyle fractures: a longitudinal prospective MRI study. Dento Maxillo Fac. Radiol. 51 (3), 20210148 (2022).

Guo, L., Meng, X. & Wu, Z. [Clinical application of disc reduction and anchorage for diacapitular condylar fracture with disc displacement]. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za zhi = zhongguo Xiufu Chongjian Waike Zazhi = Chinese. J. Reparative Reconstr. Surg. 36 (5), 587–591 (2022).

Choi, K. Y., Yang, J. D., Chung, H. Y. & Cho, B. C. Current concepts in the mandibular condyle fracture management part I: overview of condylar fracture. Archives Plast. Surg. 39 (4), 291–300 (2012).

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFC2509100); Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (23Y31900400); National Natural Science Foundation of China (82370984); Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (22S31903400); Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine Affiliated Ninth People’s Hospital (2022 hbyjxys-zjs).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors gave their final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Lingtong Bu: Contributed to conception and design; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; drafted manuscript. Yuxin Zhang: Contributed to analysis and interpretation; drafted manuscript. Xiang Wei: Contributed to design; critically revised manuscript. Qingyu Xu: Contributed to interpretation; critically revised manuscript. Zixian Jiao: Contributed to design; analysis; critically revised manuscript. Chi Yang: Contributed to design; acquisition; critically revised manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

An ethical approval has been given by Shanghai Research Center for Oral Diseases (SH9H-2019-T315-1).

Patient consent statement

The letter of informed consent was signed before the proceeding of treatment, clarifying all medical and imaging documents were approved for experimental study or article publication without the revelation of personal privacy under the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bu, L., Zhang, Y., Wei, X. et al. A 2 year follow-up self-controlled study on morphological changes in the musculoskeletal apparatus after conservative treatment of condylar head fracture. Sci Rep 15, 16638 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01866-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01866-7