Abstract

This study addresses the problems of critical conduction mode (CRM) Boost-PFC circuit switch tubes(switch tubes are semiconductor devices like MOSFET that control electric current on/off states) with large opening voltages that lead to high opening loss and high dv/dt, which result in poor electromagnetic interference (EMI). This study also proposes an improved soft-switching constant on time (COT) control method that adaptively realizes ZVS at low instantaneous input voltage values and valley conduction at high instantaneous input voltage values. The EMI performance of the circuit was improved by reducing the switching voltage, switching loss, and the dv/dt of the switch tube. This study discusses the Boost-PFC circuit of the CRM mode, the principle and working process of the proposed control method, analyzes the impact of the proposed control method on the EMI characteristics of the circuit, and designs key parameters. Finally, the simulation and experimental results demonstrate the input and output characteristics, efficiency curves, and EMI curves of the prototype with a power of 20–40 W, an input of 176-277Vac, and an output constant voltage of 430Vdc, which verify the effectiveness of the proposed control method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the global emphasis on environmental protection and the pressure of energy shortage, the shipbuilding industry is also actively exploring and promoting new energy power systems, and promoting the development of low carbon emissions, low pollution, and low noise in the shipping industry by using renewable energy instead of fuels1,2. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) has issued relevant regulations and standards to promote the global implementation of the requirement that the sulphur content of marine fuel should not exceed 0.50% m/m, which has greatly increased environmental protection requirements and further promoted the development of green ships3. According to statistics, the size of China’s electric ship market will reach 9.48 billion yuan in 2021, a year-on-year increase of 12.9%, which shows that electric ships will be used in more in-land shipping in the future. In the case of oil depletion, the new energy power system plays a good renewable role, and its high efficiency can greatly reduce the energy con-sumption and emissions of ships4. Electric ships are about 90% more energy efficient than conventional fuels.

The new energy ship power system is a shipborne energy device that conforms to the current international trend of energy conservation and emission reduction, and its main available clean energy is wind energy, bioenergy and solar energy. Among them, the basic principle of wind energy is to use wind power generation as a power source and build a power system, such as the use of multi-layer sails to provide auxiliary power for ships, through the air chamber, suspension control box, electronic control devices, mechanical drives and other physical equipment to control wind power generation, to provide auxiliary power for ships, at present, a small number of ships have begun to apply wind power generation energy system, but limited by power generation, the proportion of wind power generation applied to the main power is still very low5; The application of bioenergy in marine power systems is mainly focused on biodiesel. However, the unstable cost of raw materials used in bioenergy production restricts the economics of bioenergy power systems. On the other hand, taking biodiesel as an example, its calorific value is about 10% lower than that of diesel, so it cannot be independently used as a marine fuel, and the blending ratio with diesel cannot be too high, so the scale of promotion and application in ship power systems has been limited6; The application of solar energy in powered ships is mainly concentrated in solar fuel cells, because the ship sailing in the ocean without shelter, solar power generation is often in a state of full power, and the ship projection plane is large, creating favorable conditions for the laying of solar photovoltaic panels. Therefore, solar photovoltaic power generation has a good development prospect as the main energy replenishment channel for electric ships7. In recent years, it is also common to report that electric ships using photovoltaic power generation at home and abroad, such as Norway’s “Viking Princess” and Shanghai’s “Shangdeguosheng” have introduced solar power generation as a supplementary power supply, and built a hybrid power system containing photovoltaic power generation to save traditional fuels8. It can be seen that the new energy represented by photovoltaic and energy storage has been gradually promoted to modern ships, forming a new Marine power system containing photovoltaic, energy storage, synchronous generator multi-type power supply mix. With the rapid development of high-power power electronic devices, the performance of Marine electric propulsion technology has gradually improved, the traditional power system has transmuted into a “comprehensive power system”, and power electronic devices have become an indispensable part of new Marine power system9,10. Among them, the boost circuit, owing to its simple structure and low production cost, is widely used in various parts of integrated power systems of ships11.

The performance of the boost circuit directly affects the power quality and operational efficiency of a ship’s “integrated power system.” However, the boost circuit has issues, such as high switch tube loss owing to the high opening voltage when the switch tube is turned on and the dv/dt problem12 (The meaning of “opening voltage” is the maximum voltage in the overlapping area of voltage and current when the switch is turned on). These problems negatively impact the efficiency and EMI characteristics of the boost circuits13,14,15,16. Therefore, the boost circuit is operated in the CRM in practical applications to achieve low-voltage conduction of the switch tube and reduce the opening loss, improving the power supply efficiency and the EMI characteristics of the power supply17,18,19. Lyu20 proposed an analysis of the circuit’s parasitic parameters to obtain the optimal conduction point of the circuit’s switch tube, providing a guiding method to achieve ZVS and valley switching (VS) for the Boost-PFC circuit switch tube. However, this method requires a significant calculation and a complex control process, which is challenging to popularize. Lin21 proposed a method to detect the voltage across the switch tube and control the switch tube conduction, which requires compensation. The sampling circuit in this method is not isolated from the main power circuit, which leads to significant interference signals and increased power losses in the detection circuitry. Liu22 proposed an optimization method for zero current detection circuits, which does not achieve the purpose of ZVS for the circuit switch tube despite the circuit switch tube being in a hard-switching state. Wei23 and Zhu24 proposed the use of auxiliary switch tubes to achieve ZVS of the main circuit switch tube, achieving ZVS and low switching noise for the circuit; however, the proposed circuit is complex, challenging to implement, and limits its application. Qian25 proposed an isolated zero-crossing detection circuit that achieved isolation from the main circuit and low-voltage conduction; however, the proposed detection circuit has poor precision and does not consider the impact of parasitic parameters.

This study proposes a COT control method combined with slope zero-detection control, which achieves ZVS or valley voltage conduction of the switch tube by detecting the voltage signal slope on the auxiliary winding of the boost inductor to enhance the conversion efficiency of the boost circuit, reducing the opening loss and EMI interference of the Boost-PFC circuit.At present, demagnetization detection is one of the most widely used methods for identifying valley voltage. This method achieves valley opening through a delay circuit composed of R and C. However, the design of this RC delay circuit is difficult as its recognition accuracy is insufficient, which generally leads to premature conduction of the switching transistor before it reaches the valley. This limits the valley voltage that the switching transistor of the circuit cannot reach when it is turned on. By contrast, the proposed control method excludes a delay module, simplifies the detection and calculation processes, and is adaptable. Additionally, it effectively reduces the conduction voltage of the switch tube, improves the efficiency of the switching power supply, reduces the dv/dt of the switch tube conduction, and improves the EMI characteristics of the circuit. This study focuses on the principle and working process of the proposed control method, discusses the impact of the proposed control on the EMI characteristics of the circuit, and designs key parameters in conjunction with the main circuit. Computer simulation analysis was performed, and a prototype was designed to measure the input and output, efficiency, and EMI characteristics of the prototype with an output voltage of 430Vdc, output power of 20–40 W, and input voltage of 176-277Vac, verifying the effectiveness of the proposed control method.

Materials and methods

CRM Boost-PFC circuit

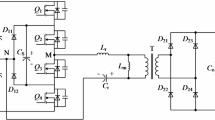

Figure 1 illustrates a schematic diagram of the Boost-PFC circuit in the CRM mode. Figure 2 illustrates the main waveforms of the switching cycle.

Based on the operating characteristics of the boost circuit, the operating process of the main circuit under the soft-switching COT control method can be divided into four stages, as illustrated in Fig. 3. The working process analysis is based on the following assumptions: (1) Switch tube Q is a non-ideal device with a total equivalent capacitance of Cj at both ends, and the other power devices are ideal; (2) The output capacitance was sufficiently significant to assume that the load voltage remained unchanged when the switch tube was turned on.

Mode 1: Corresponds to the [t1-t2] phase of the working waveform, as shown in Fig. 3a. Before time t1, switch tube Q is off, and diode D is on. At time t1, the inductor current reaches its peak value, the switch tube Q turns off, and both the input power supply and inductor store energy, simultaneously charging the parasitic capacitance Cj of the switch tube and causing the voltage on the parasitic capacitance Cj to reach the output voltage of the boost circuit. At time t2, charging ends, diode D becomes conductive, and the voltage of the parasitic capacitance Cj is equal to the output voltage V0.

Mode 2: Corresponds to the [t2-t3] phase, as shown in Fig. 3b. After time t2, the switch tube Q of the boost circuit is off, diode D is on, and the inductor and input power supply provide energy to the output capacitor and load. The main device state expressions for this period are as follows:

At time t3, the energy stored in the inductor depletes, the diode current drops to zero, the diode is turned off, the inductor current is zero, and the parasitic capacitance of the switch tube begins to discharge back into the input source.

Mode 3: Corresponds to the [t3-t5] phase, as shown in Fig. 3c. At time t3, the energy stored in the inductor depletes, and the diode current naturally drops to zero, achieving zero-current turn-off. However, the voltage on the parasitic capacitance Cj equals the output voltage, which is higher than the input voltage; hence, inductor L forms a resonant circuit with parasitic capacitance Cj and input capacitance C1. The current begins to flow back from the parasitic capacitance Cj through the inductor to the input capacitor C1: From 1/4 of the resonant cycle to time t4, the voltage on the inductor is zero, the zero current detection (ZCD) pin voltage crosses zero, the reverse current reaches its peak through resonance, and the parasitic capacitance-voltage equals the input voltage. The widely used demagnetization detection control method controls the switch tube to conduct at time t4 but fails to achieve the lowest voltage conduction. Theoretically, it is essential to wait for another 1/4 of the resonant cycle after time t5, when the voltage on the parasitic capacitance reaches its lowest value, which is the voltage across the switch tube DS reaches its lowest value. The switch tube is turned on at this time to achieve the best state of low-voltage conduction for the switch tube. This technology is called valley conduction control technology for circuits. The theoretical analysis demonstrates that when the instantaneous value of the input voltage exceeds half of the output voltage, the switch tube can achieve valley voltage conduction, achieving ZVS. The valley conduction control technology of the boost circuit achieves low-voltage conduction or ZVS of its switch tube, effectively reducing dv/dt when the switch tube is turned on and improving the EMI characteristics of the circuit. At time t5, the voltage at both ends of the switch tube is the valley voltage 2vin-V0 or 0, the voltage across the diode is 2V0-2vin or V0, and the inductor current is zero.

Mode 4: Corresponds to the [t5-t6] phase, as shown in Fig. 3d. At time t5, the switch tube Q changes from off to on. Next, the Boost circuit’s switch tube Q remains in the on state. The input power supply provides energy storage to the inductor, and the output capacitor supplies power to the load until time t6. The switch tube Q turns off. During this period, the main device state expressions are:

At time t6, the inductor current reaches its peak value, and the switch tube turns off. The voltage across the diode decreases, and the state of each device remains the same at time t1, completing the switching cycle and leading to the next cycle.

Improved soft switching COT control

The PFC circuit in this study adopts an improved soft-switching COT control method, a commonly used control method in the peak current control mode, as illustrated in Fig. 4. Additionally, it combines the valley conduction control technology when the switch tube is turned on, achieving ZVS in the area and valley opening, thereby enhancing the circuit’s performance.

This paper proposes a slope zero-detection valley-voltage conduction control method that achieves ZVS for the Boost circuit when the instantaneous value of the input voltage is approximately half of the output voltage and achieves valley conduction when the instantaneous value of the input voltage exceeds half of the output voltage. The method does not contain a delay module, has a simple structure, and can accurately identify voltage valleys.

Figure 5 illustrates the detection circuit schematic. The proposed detection circuit consists of three parts: (1) ZCD voltage zero detection circuit; (2) ZCD voltage slope zero detection circuit; and (3) Switch judgment circuit. Figure 3 shows the circuit’s operation process.

The ZCD voltage zero-detection circuit includes a comparator and an RS flip-flop. When the level of the ZCD pin is lower than the reference zero level, the RS flip-flop outputs a high level to turn on switch Sx, and the level signal on the ZCD pin is transmitted to the slope zero detection circuit. When the slope of the ZCD signal is below Vrefs2, vx triggers the RS flip-flop, thereby outputting a high level from vgs and driving the MOS tube to conduct. The control process is as follows.

Figure 6 shows the key waveform diagram of the turn-on signal control circuit, which illustrates the circuit’s control process according to the timing in the schematic diagram. The auxiliary-side conduction time detection information is obtained through the ZCD on the primary-side auxiliary winding.

[t1–t2]: Before time t1, the switch tube is turned on, and the diode is turned off. At time t1, the switch tube turns off, the secondary-side diode conducts, the auxiliary winding voltage is proportional to the secondary-side output voltage, and a stable output voltage is output until the secondary-side conduction time ends at time t2, during which DeE outputs a low-voltage signal. When Sx is off, the slope-detection circuit does not work, A outputs a zero level, vx maintains a high level and does not act, and the switch tube does not operate.

[t2–t3]: At time t2, the voltage across the switch tube drain and source is equal to Vin+nV0, which is greater than the input voltage Vin. The current flows back to the input source from the switch tube DS capacitor through the transformer’s primary side equivalent inductor. The voltage between the switch tube DS and the ZCD voltage decreases until time t3. When the voltage across the switch tube DS equals the input voltage, the voltage across the transformer equivalent inductor is 0, and the ZCD voltage equals 0, triggering the slope detection circuit to start working.

[t3-t4]: After time t3, a zero-voltage signal is detected. DeE outputs a high-level signal, making the switch Sx signal a high-level signal and controlling the switch Sx to conduct. The slope detection circuit starts working and detects a negative slope. However, because the input voltage is negative, the output signal value A is greater than zero. The comparator acts despite outputting a low level. Next, vx outputs a low level until time t4. The slope of the voltage change at the ZCD pin becomes zero. The output of point A is at a low level below Vrefs2. The comparator acts and outputs a high level, whereby vx outputs a high level, driving the signal vgs to output a high level. The switch tube conducts, leading the zero detection circuit switch Sx to turn off.

Between times t3 and t4, if the instantaneous input voltage is in the low-instantaneous-value phase of the sinusoidal input voltage, as illustrated in Fig. 6, and when the instantaneous value of the input voltage is below V0/2, after resonance, the voltage across the switch tube will directly reach zero. This enables the body diode of the switch tube to conduct, thereby achieving zero-voltage conduction in the Boost-PFC circuit switch tube. If the instantaneous input voltage is in the high instantaneous value phase of the sinusoidal input voltage, as shown in Fig. 6b, when the input voltage exceeds V0/2, the minimum voltage across the switch tube exceeds zero, leading to switch tube conduction at the valley voltage. Moreover, the conduction of the switch tube can reduce the switch-tube loss and dv/dt.

After time t4, because switch Sx of the ZCD zero detection circuit is off and DeE is also at a low level, the slope detection circuit does not work. Therefore, all signals maintain the previous state until the turn-off signal CS controls the switch tube to turn off.

[t4–t5]: At time t4, the switch tube turns on, and vgs maintains a high level until time t5. When the vCS level exceeds the reference level vrefs1, the comparator COM3 outputs a high level, and the RS flip-flop outputs a low level, causing the switch tube to turn off. The circuit state at time t5 was consistent with that at time t1, and the switching cycle continued.

Impact of improved COT control on EMI

When the switch tube is turned on during non-valley conduction, dv/dt can be expressed by the following formula:

where V0 is the output voltage and tr is the time required for the switch tube to turn on.

After the Boost circuit uses the valley conduction technology, the turn-on voltage vvalley of the switch tube becomes

By combining the valley conduction, dv/dt when the switch tube is turned on can be expressed by the following formula:

where V0 is the Boost-PFC output voltage, Vin is the amplitude of the input voltage, and θ is the phase angle of the input voltage.

According to formulas (3) and (5), the values of dv/dt at different \({\text{\varvec{\uptheta}}}\) can be calculated, as shown in Fig. 7. It can be seen from the figure that the dv/dtr of the boost circuit during the turn-on of each input voltage is significantly reduced, after using the valley conduction technology.

Key parameter design

Using the COT control strategy, when the switch tube is in the conduction phase and according to the inductor characteristics, we derive

where Vin is the amplitude of the input voltage, θ is the phase of the input voltage, and L is the inductance of the boost circuit. Based on the output power and estimated efficiency of the front end Boost-PFC circuit, the instantaneous average value of the input current i can be calculated as:

where P0 is the output power and η is the efficiency of the Boost circuit.

Using the formula above, the conduction time of the switch tube during COT control can be obtained as follows:

The conduction time of the switch tube of the boost circuit is related only to the input power, inductance, and magnitude of the input voltage. Therefore, under specific conditions of input power, inductance, and input voltage, the conduction time of the switch tube is constant; hence, the name is COT control.

The turn-off time of the switch tube within this period can be derived as:

The turn-off time of the switch tube is variable, indicating that the COT control method is a variable frequency control method.

When the switch tube is turned off, the voltage increases across its ends, mainly for charging the capacitors at both ends of the switch tube. Therefore, the rise time can be expressed as:

where Cj represents the equivalent capacitance at both ends of the switch tube DS.

Owing to the use of valley conduction technology, a resonance process, which consists of the Boost inductor and its parasitic capacitance, the capacitance Cj at both ends of the switch tube DS, and the filter capacitor C1 after the bridge occurs when the switch tube turns on, as illustrated in Fig. 6. When the resonance reaches the lowest point of the voltage across the switch tube, the switch tube conducts. However, because the capacitance of the filter capacitor after the bridge is much larger than the equivalent capacitance Cj at both ends of the switch tube DS, the filter capacitor after the bridge can be considered as a short circuit. The time duration for this resonance process can be expressed with the formula:

The switching frequency of the proposed soft-switching COT control method is:

The PFC circuit designed in this study has an output power of 40 W, output rated voltage of 430 V, AC input voltage range of 176–305 Vac, and an estimated efficiency of 96%. Because the trise and tfall times are very short, they can be ignored in the inductor design. Therefore, according to the formula, we obtain:

The minimum frequency in the CRM mode to 20 kHz, and the inductance value is 1.1 mH under the condition that satisfied the formula.

The relationship between the DC bus electrolytic capacitor C0 and the output voltage ripple ΔVo_ac is shown in the formula. After the AC input voltage is rectified by the rectifier bridge, its frequency is fac = 100 Hz. When the maximum average output current I0 is 0.1 A, and the maximum ripple ΔVo_ac is 15 V, the output electrolytic capacitor can be taken as 450 V/33 uF under the condition that meets the formula:

Results and discussion

Simulation results

Table 1 illustrates a simulation circuit for the boost circuit, which lists the main parameters of the simulation model based on the circuit principles and control strategies and the designed circuit parameters.

Input characteristics

Figure 8 illustrates the input characteristic simulation waveform of the designed front-end boost circuit. The experimental waveform demonstrates that the boost circuit has good input characteristics, which can achieve good power factor correction, complying with the IEC1000-3-2 Class C-related standards.

The circuit simulation results demonstrate that under an input of 176Vac–277Vac, with half-load to full-load output, the minimum PF was 0.965, and the maximum THD was 9.62%, meeting the relevant harmonic standards.

Soft switching characteristics

Figure 9 illustrates the voltage and current simulation waveforms of the Boost-PFC circuit’s switch tube under the input voltage of 176 Vac–277 Vac/50 Hz at full load. Before the switch tube current rose, the voltage across its ends had already dropped to the valley voltage. The current was zero when it turned on, achieving zero current turn-on of the boost circuit. The voltage across the switch tube was at the valley voltage when it turned on, significantly reducing dv/dt when the switch tube turned on and enhancing the power supply EMI characteristics.

Figure 10 shows the voltage and current waveforms of the diode when the input voltage was 176 Vac–277 Vac/47–63 Hz or 171 Vdc–275 Vdc under different loads. Before the diode turned off, its current had already dropped to zero, achieving soft switching of the diode.

Valley conduction characteristics

Figure 11 shows two detection methods for the valley conduction characteristics of the switch tube of the boost PFC circuit at the peak of the power-frequency period under a full load. Operating the switch tube of the boost circuit at the valley voltage reduced the switching loss of the switch tube and the dv/dt of the switch tube, thereby enhancing the EMI performance of the circuit. Figure 11 shows the soft-switching characteristics of the boost circuit. The simulation demonstrates that at a 220 V input, the PFC circuit operated as a constant voltage output, with an output voltage of 430 Vdc. Moreover, it can be seen that the slope detection method further reduces the conduction voltage of the switch tube.

Experimental results

In this study, a 40 W prototype was built to test and verify the correctness of the theoretical analysis and simulation. Table 2 illustrates the prototype parameters, while Fig. 12 presents the prototype.

Input and output characteristics

Figure 13 illustrates the input voltage and current waveforms when the input voltage was 176 Vac–277 Vac/47–63 Hz or 171 Vdc–275 Vdc under different loads, indicating that the input current effectively follows the input voltage owing to good input characteristics.

When the prototype was at the rated input of 50–100% output, the PF value exceeded 0.96, and the THD value was approximately 10%, as shown in Fig. 14. When the prototype was at 277 V input, 50–100% output, the PF value exceeded 0.91, and the THD value was approximately 20%, complying with the IEC1000-3-2 Class C-related standards.

Figure 15 illustrates the voltage and current of the Boost-PFC inductor when the input voltage was 176 Vac–277 Vac/47–63 Hz or 171 Vdc–275 Vdc, under different loads.

Figure 16 shows the output voltage when the input voltage was 176 Vac–277 Vac/47–63 Hz or 171 Vdc–275 Vdc under different loads. Additionally, the Boost-PFC circuit had a stable output voltage, and its ripple rate was approximately 3%.

Soft switching characteristics

Figure 17 illustrates the voltage and current waveforms for the Boost-PFC circuit’s switch tube under different loads when the input voltage was 176 Vac–277 Vac/47–63 Hz or 171 Vdc–275 Vdc. Before the switch tube current rose, the voltage across its ends had already dropped to the valley voltage, and the current was zero when it turned on, achieving zero current turn-on of the boost circuit. The voltage across the switch tube was at the valley voltage when it turned on, significantly reducing dv/dt when the switch tube turned on, enhancing EMI power supply characteristics.

As shown in Fig. 18, at rated input and output, the valley voltage of demagnetization detection method is 363 V, while the valley voltage of slope method (the method proposed in this paper) is 332 V. The conduction voltage drops by 31 V, which means a reduction in switching losses and an improvement in efficiency.

Figure 19 illustrates the voltage and current waveforms of the diode when the input volt-age was 176 Vac–277 Vac/47–63 Hz or 171 Vdc–275 Vdc under different loads. Before the diode turned off, its current had already dropped to zero, achieving soft switching of the diode.

EMI characteristics

When the switch tube was turned on, the conduction voltage decreased as the dv/dt decreased, enhancing the circuit EMI characteristics. Figure 20 shows the testing equipment and environment for conducting EMI on the prototype tested in this article. Among them, the EMI receiver is FFT3010 produced by AFJ company, and LISN is LT32 produced by AFJ company.

Figure 21 compares the EMI characteristics before and after the improvement of the boost circuit. Among them, the QP Limit Value represents the quasi peak limit, with a frequency range of 9 kHz-30 MHz; The AV Limit Value represents the average limit, with a frequency range of 150 kHz-30 MHz. In addition, the QP and AV are examples of EMI test curves for actual prototypes. The QP represents the quasi peak value, and the AV represents the average value.The EMI margin improved from 0.4 to 6.3 dBuV, indicating that the proposed control method enhances the EMI characteristics of the CRM Boost circuits.

Input and output characteristics

Figure 22 compares the efficiencies of the Boost-PFC circuit before and after improvement. The power supply is provided by CHROMA 62020H-150S, and the load is provided by CHROMA 63203E-600-210. Calculate the efficiency of the proposed converter based on the power displayed on these two devices. After using the improved COT control method, the full-load efficiency of the power supply increased from 94.83 to 95.11%, thereby enhancing the efficiency.

Conclusion

This study proposed an improved soft-switching COT control strategy for Boost-PFC circuits, which enables the conduction of the switch tube of the boost circuit at the valley when the instantaneous value of the input voltage exceeds half of the output voltage. Consequently, the ZVS soft switching was achievable when the instantaneous value of the input voltage was approximately half of the output voltage. The simulation and experimental results demonstrate that the proposed control method effectively reduced the turn-on voltage of the Boost-PFC circuit switch tube and the turn-on loss of the circuit and effectively reduced dv/dt when the circuit switch tube was turned on, thereby improving the EMI performance of the circuit.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Lan, H., Bai, Y. F. & Wen, S. L. Energy saving and emission reduction evaluation of large oil tanker with solar power. Acta Energ. Sol. Sin. 36(11), 2738–2743 (2015).

Li, H. Development of electric ship under the vision of carbon peak in transportation industry. Ship Eng. 44(11), 76–78 (2022).

Fan, A. L., He, Y. P. & Yan, X. P. Concept and key technologies of intelligent new energy ship. Ship Eng. 42(3), 9–14 (2020).

He, Y. P., Yan, X. P. & Fan, A. L. Development status and prospects of ship intelligent energy efficiency management technology. J. Harbin Eng. Univ. 42(3), 317–324 (2021).

Pu, L. S. Current situation and development trend of ship new energy power system. Mar. Equip. Mater. Mark. 32(1), 100–102 (2024).

Zhang, Z., Jiang, G. H. & Chen, Y. J. Effects of performance of marine diesel engine by combustion mixing a small proportion of biodiesel. China Oils Fats 48(2), 70–74 (2023).

Cong, Y. Application of photovoltaic power generation technology on large ships. China Water Transp. 18(9), 69–70 (2018).

Sun, X. J., Song, E. Z. & Yao, C. Research status of key technologies for energy management system of marine hybrid propulsion systems. China Mech. Eng. 33(4), 469–481 (2022).

Ma, W. M. Typical applications of power electronics in naval ship power systems. Trans. China Electrotech. Soc. 26(05), 1–8 (2011).

Chi, Y. & Minyou C,Yi, Y. H. Novel adaptive multi-clustering algorithm-based optimal ESS sizing in ship power system considering uncertainty. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 33(1), 307–316 (2018).

Pang, K. W., Guo, C. X. & Zhang, M. The application of improved two-phase interleaved boost circuit in photovoltaic system. Ship Sci. Technol. (8), 99–103. (2018).

Goswami, R. et al. Differential mode active EMI filter design for a boost power factor correction AC/DC converter. Emerging and selected topics in power electronics. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 7 (1), 576–590 (2019).

Esfetanaj, N. N. et al. Analytical modeling of 9-150 kHz EMI in single-phase PFC converter. In IECON 2019 -45th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society 4689–4693 (IEEE, 2019).

Pourmahdi, M., Heydari-Doostabad, H., Ghazi, R. & O’Donnell, T. Buck–Boost common ground bridgeless PFC (CGBPFC) rectifies with positive/negative output. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 37(2), 1272–1282 (2022).

Liu, Y. N. Research on EMI mechanism based on Boost PFC radiation. Jiangsu University (2019).

Yao, K., Li, J., Shao, F. & Zhang, B. Parallel fixed switching frequency CRM and DCM boost PFC converter with high power factor. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 37(3), 3247–3258 (2022).

Song, H. et al. Non-linear control of a boost PFC converter with a small inductor based on feedforward correction and frequency variation. IET Power Electron. 15(8), 675–688 (2022).

Zhou, G. & Xu, J. Digital peak current control for switching DC–DC converters with asymmetrical dual-edge modulation. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 56(11), 815–819 (2009).

Yang, X. I., Gu, G. S., Yang, Z. & Mou, Y. D. Study of APFC based on boost technology and average current mode. Digit. Technol. Appl. 37(10), 132–133 (2019).

Lyu, D., Tong, Q. L., Min, R. & Zou, X. H. Optimization of soft-switching time of CRM boost circuit based on piecewise equivalent capacitance model. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Tech. Nat. Sci. Ed. 49(03), 24–28 (2021).

Lin, A. N. Research on interleaved Boost PFC converter based on CRM. South China University of Technology (2020).

Liu, T. Y. Research on CRM Boost PFC converter based on GaN device. China University of Mining and Technology (2019).

Wei, L., Liu, S., You, W. Y., Zhang, Y. C. & Yao Y T. A novel Lnterleaved boost converter with Non-Resonant Soft-Switching. Trans. China Electrotech. Soc. 32(03), 172–183 (2017).

Zhu, L. J. Research on interleaved boost PFC converter with soft-switching technology. Yanshan University (2012).

Qian, B. Research of High efficiency isolated high step-up converter. Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics (2016).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the 2023 Annual Fuzhou Marine Research Institute “Top Talents Recruitment” Science and Technology Project, grant number 2023F06, the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province, grant number 2023J011400, and the Education and Research Project for Young and Middle-aged teachers of Fujian Provincial Department of Education, grant number JAT220317, the Minjiang University Talent Introduction and Scientific Pre-research Project, grant number MJY23013, the Science and Technology Key Project of Fuzhou, grant number 2022-ZD-021.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, H.C., J.X. and S.Z.; methodology, H.C., J.X. and S.Z.; validation, H.C., S.Z., J.L. and C.L.; formal analysis, H.C., S.Z., and J.L.; investigation, H.C.; resources, S.Z. and C.L.; data curation, H.C.; writing—original draft preparation, H.C.; writing—review and editing, J.X., C.L. and Z.W.; visualization, H.C.; supervision, J.X., Z.W. and C.L.; project administration, H.C. and J.L.; funding acquisition, H.C., C.L. and Z.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, H., Xiao, J., Lin, J. et al. Improved COT control strategy for CRM Boost-PFC circuits applied to marine integrated power systems. Sci Rep 15, 17239 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01888-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01888-1