Abstract

The scavenger receptor CD36 has gained increasing interest in cancer research, with various functions in cell metabolism, angiogenesis, and immune response. This study aimed to investigate the molecular role of CD36 expression on tumor vasculature of advanced high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC) tissues and its prognostic implication. Immunohistochemical staining for CD36 was performed on whole tissue slides of 109 patients with advanced HGSOC. Patients were divided into two groups based on CD36 expression, i.e. positive versus negative, and correlated to clinicopathologic and survival data. RNA sequencing, metabolomics, and proteomics data were correlated to the CD36 expression within a subpopulation. CD36 expression in tumor vasculature was significantly associated with unfavorable overall survival (OS), both in univariate (HR 1.71, p = 0.039) and multiple Cox regression analyses (HR 1.91, p = 0.021), considering age, FIGO stage, postoperative residual tumor, and bevacizumab treatment as covariates. Positive CD36 expression was significantly associated with postoperative residual tumor, reflecting high tumor-burden. (p = 0.042). RNA sequencing from isolated tumor cells revealed an activated ‘regulation of lipolysis in adipocytes’ pathway significantly associated with CD36 expression. Co-association gene expression network analysis revealed increased ribosomal activity and protein translation in tumor cells of CD36-positive samples. Proteomics analysis of ascites showed three overexpressed proteins involved in lipid metabolism (LCN2, CFHR1, and CFHR4) out of 21 significantly deregulated proteins. Metabolomic analyses of serum showed a significant decrease of 60 glycerophospholipids (mainly unsaturated ones) and eight amino acids, four essential proteinogenic, in patients with CD36 positive vessels. CD36 intratumoral vessel expression was associated with unfavorable OS in patients with advanced HGSOC. Our analyses support the role of CD36 in tumor metabolism, possibly via CD36+-endothelial cell-mediated glycerophospholipid/oxLDL uptake. Signs of increased tumor metabolism were found, as well as a decrease of specific metabolic building blocks, indicating a higher—presumably CD36–mediated—uptake capacity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the most lethal gynecological malignancy. Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is usually diagnosed at an advanced stage due to unspecific symptoms at early stages and limited screening options. The 5-year survival rate is still only at around 45%1,2 and innovative therapy concepts are urgently needed to improve patient survival and therapy efficacy.

A potentially interesting new therapy-targeted could be the transmembrane glycoprotein CD36.

Belonging to the class B scavenger receptor family, CD36 has become of increasing interest in cancer research, including ovarian cancer. CD36 is expressed on the surface of various cells, such as dendritic cells (DCs), monocytes, microvascular endothelial cells, adipocytes, podocytes, and platelets. In malignant disease, CD36 is also expressed on tumor cells, stromal cells, and tumor associated immune cells3,4.

CD36 has various functions in normal and abnormal tissue, including important functions in cell metabolism, angiogenesis and immune response. Additionally, CD36 functions as a receptor for lipids, especially long chain fatty acids (LCFA) and oxidized low-density lipoproteins (oxLDL)5. It has been discovered that oxLDL and fatty acids (FA) are internalized in endothelial cells via CD366,7. Via transfer of absorbed FAs to the mitochondria, CD36 provides energy for cell metabolism5.

An altered metabolism of cancer cells has been recognized as a hallmark of cancer8. For that, cancer cells use several mechanisms, metabolic support from stromal cells or adipocytes in the tumor microenvironment (TME)9, as one example. In ovarian cancer, interaction of cancer cells between stromal cells and stromal (omental) adipocytes in the TME has been reported. Cancer cells can induce lipolysis in adipocytes, therefore providing lipids for cancer metabolism10. Yang et al. identified a mechanism for stromal metabolic support by increased glutamine production from cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and a potential treatment target in an ovarian cancer mouse model11. It was also shown that tumor cells can take up extracellular lipids from the TME for metabolic tumor support (PMID: 23671091). CAFs in the TME can interact with cancer cells in various ways, by classical paracrine signaling or via exosomes, thereby promoting tumor growth and metastasis. TGBF1 in fibroblast exosomes can support EMT in ovarian cancer cells12 and increased lipid secretion (such as fatty acids and phospholipids) supports tumor metabolism13. It has been shown, that ovarian adipose stromal cells metabolically support tumor growth through arginine metabolism14.

In co-culture experiments of ovarian cancer cell lines with primary human omental adipocytes, Ladanyi et al. found an increase in CD36 expression and thereby increased exogenous fatty acid uptake, as well as increased CD36 gene expression in omental metastases compared to primary tissues of ovarian cancer patients4.

Associated with metastasis and tumor progression in various cancer entities5,15, CD36 levels have been observed to rise with increasing tumor burden, especially in a metastatic situation5. Low expression of CD36 mRNA was found to be associated with improved prognosis in ovarian and colon cancer16. CD36 gene expression was found to be highly upregulated in recurrent HGSOC tissues compared to the corresponding primary tumors17.

Several studies have investigated anti-cancer strategies concerning CD36. These include inhibition of FA uptake and promotion of TSP-1 binding to CD36. Unfortunately, most drugs, which have reached the clinical trial phase, have been found to be either ineffective or to cause severe side effects5. Recently, Wang et al. achieved a significant reduction in tumor growth in melanoma engrafted mice treated with a CD36 inhibitor and/or a PD-1 inhibitor3.

Bevor addressing CD36 as potential therapy target in EOC, its molecular role needs to be further elucidated as data derived from this tumor entity is limited. Wang et al. generated a peptide derived from prosaposin (psap), which stimulated p53 & TSP-1 and tested this anti-tumorigenic therapy in a patient-derived tumor xenograft model, successfully promoting tumor regression. They also found CD36 expression in all 12 investigated primary human ovarian cancer cell lines derived from ascites of HGSOC patients and in 97% (130/134) of HGSOC tissues on a tissue microarray (TMA) compared to 61% in normal tissues, with even higher staining intensity in metastatic tissues18.

The aim of this study was to investigate the molecular role of CD36 expression on tumor vasculature of advanced high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC) tissues and its prognostic implication.

Materials and methods

Study design

Patients treated for EOC at the Medical University of Vienna between 2004 and 2018 were selected from a prospectively maintained database. Only patients with advanced stage (FIGO III – IV) HGSOC were included. Further inclusion criteria were availability of representative tumor samples and respective clinical and follow up data. Patient samples were originally collected at primary diagnosis (diagnostic laparoscopy or primary debulking surgery) prior to any anti-tumor therapy and later retrieved from the pathological archives of the Medical University of Vienna. Histology was confirmed by gynecologic pathologists and clinical and follow-up data were retrieved from electronic medical records. The study was approved by the ethical review board (EK Nos. 1966/2020 and 1892/2021) and all patients gave their written informed consent.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed on 2 μm thin whole tissue sections of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) ovarian tumor tissues.

After rehydration in ethanol-series, antigen retrieval for CD36 staining was performed in sodium citrate buffer at pH 6.0 for 15 min at 95 °C using the KOS Multifunctional Microwave Tissue Processor (Milestone Medical, Sorisole, Italy). IHC staining procedure started with peroxidase blocking in 3% H2O2 and a blocking solution (Ultravision Protein Block, Thermo scientific, TA-125-PBQ) for 7 min, followed by primary antibody incubation of 30 min at room temperature, followed by incubation with Ultravision HRP Polymer (Thermo Scientific™ TL-015-HAJ). Slides were stained with DAB (Vector laboratories; SK-4100) and counterstained in Mayer’s hemalum. Anti-CD36 HPA002018 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) was used at a dilution of 1:100. CD36 stained slides were scanned with Vectra Polaris (Akoya Biosciences, Massachusetts, USA) and evaluated digitally and optically via light-microscopy.

Scoring of CD36 staining was performed manually by two independent investigators, including one dedicated gynecological pathologist. In case of discrepancy, consensus was achieved.

CD36 expression was determined semi-quantitatively as the percentage of vessels that presented positive for CD36 (0-100%). Staining intensity was evaluated by a 4-tier grading system, (negative, weakly positive, moderately positive, and strongly positive).

Multi-omics analyses

From a subgroup of these patients (n = 22, 20.2%), extensive molecular characterization of blood, ascites and tumor samples were available from previous studies19,20. Cytokines, metabolomics, proteomics, and RNA sequencing were performed as previously described19,20,21 and summarized briefly below.

Cytokines

Cyto- and chemokines were measured in 19 cell-free ascites and 16 serum samples on a Bio-Plex 200 System (Bio-Rad Laboratories), following instructions provided by the corresponding kits “Bio-Plex Pro Human Cancer Biomarker Assays: Panel 1”, “Bio-Plex Pro Human Chemokine Panel Assay” (both Bio-Rad Laboratories), and “Cytokine Human Magnetic 25-Plex Panel” (Life Technologies).

Metabolomics

Targeted metabolomics of 19 ascites samples and 21 serum samples was performed with AbsoluteIDQ p180 kits (Biocrates Life Sciences AG) after the guidelines from Biocrates. Samples were analyzed on an AB SCIEX QTrap 4000 mass spectrometer (Framingham, MA, USA) using an Agilent 1200 RR HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), which were operated with Analyst 1.6.2 (AB SCIEX). The chromatographic column was obtained from Biocrates. The experiments were validated using the supplied software (MetIDQ, Version 5-4-8-DB100-Boron-2607, Biocrates).

Proteomics

Untargeted shotgun proteomics analysis of 16 ascites samples was performed on a QExactive Orbitrap instrument (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA USA) coupled with an UltiMate 3000 RSLC nano system (Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Targeted analysis of selected proteins in the cell supernatant were implemented on a QQQ6490 triple quadrupole instrument (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) coupled with a Chip-nano-LC system (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

RNA sequencing

RNA of 42 EpCAM-enriched tumor cell samples from ascites and solid tumor tissue samples was isolated with the miRNeasy® Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Sequencing libraries were prepared from 200 ng total RNA with the NEBNext® Ultra™ Directional RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB). After quality assessment on a DNA High Sensitivity chip (Bioanalyzer 2100), libraries were quantified with digital PCR (QX100™ Droplet Digital™ PCR System, BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). For each lane of the Illumina HiSeq 2000 system (San Diego, CA, USA) eight libraries were pooled equimolar and sequenced for 150 bp paired ends.

Bioinformatic and statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in GNU R 4.1.2 with following R-packages: survival 3.2–13, survMisc 0.5.5, limma, and MASS 7.3–55. Survival analyses were performed by univariate and multiple Cox-regression analyses, including clinicopathologic factors as confounders. Alive patients were censored at the time of last contact. Median follow-up of the cohort (only censored patients) was 62.13 months (interquartile range, IQR [44.12; 92.12]. The optimal cut-off for a dichotomized CD36 was determined by the cutp function from the R-package MASS. To plot estimated survival curves for dichotomized CD36 abundance from the final Cox-regression models, all correcting factors were averaged. Continuous nominal values were compared between two groups with students’ t-test. Correlations of nominal variables with nominal or ordinal variables were performed using Spearman Correlations. Correlations to multiomics data were performed with limma, using the CD36 expression as independent variable and logarithmized (base 2) analytes as dependent variables. Raw p-values were corrected for multiple testing by the Benjamini-Hochberg method, yielding false discovery rates (FDR).

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 109 patients with advanced stage HGSOC treated at the Medical University of Vienna between 2004 and 2018 were included in this study. Thereof, 77 patients (70.6%) presented with FIGO stage III and 32 patients (29.4%) with FIGO stage IV HSGOC. According to non-linear remodeling of cubic splines, age was dichotomized using 65 years as cut-off.

Platinum based chemotherapy was recommended in all patients, and bevacizumab was administered to 70 patients (64.2%). 24 (22.0%) patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by intervention debulking surgery and 82 (75.2%) patients were treated with primary debulking surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy. In one case (0.9%) chemotherapy was administered without surgery and two (1.8%) patients received surgery only. Complete tumor resection (R0) was achieved in 61 (56.0%) patients.

CD36 staining

Staining intensity and percentage varied between patients. CD36 staining was found mainly on tumor vasculature of whole tissue sections (Fig. 1). Percentages of CD36 staining on tumor vasculature ranged from 0 to 100%, with a median of 0% and a mean of 22%. CD36 intensity was recorded from 0 to 3 with a median of 0 and a mean of 0.75. An H-score was calculated multiplying CD36% with staining intensity, ranging from 0 to 300, with a median of 0 and a mean of 51.07.

For further analyses, patients were divided into two groups based on this H-score. The optimal cutoff was determined using the cutp function from the R-package MASS, as described above, and yielded 73 patients in the CD36 negative group (H-score 0–10) and 36 patients in the CD36 positive group (H-score > 10). To validate the used cutoff (H-score > 10), a Cox regression model was built using splines for non-linear modelling of the association between the CD36 H-score and the hazard ration for overall survival. Figure 2 shows this association confirming the validity of the used cutoff.

Correlation with clinicopathological parameters

CD36 abundance was correlated to clinicopathological parameters, as presented in Table 1. No significant correlation between CD36 and patients’ age, FIGO stage or bevacizumab therapy was found. Interestingly, CD36 abundance was significantly correlated to residual disease after surgery (p = 0.042), with a higher rate of complete tumor resection in CD36-negative patients.

Overall survival

In a univariate Cox regression analysis, the dichotomized CD36 H-score (p = 0.039, HR 1.72), i.e. positive versus negative CD36 expression, residual disease, and age were significantly associated with overall survival. In a multiple Cox regression analysis, including age, FIGO stage, residual disease, and bevacizumab therapy as confounders, again the dichotomized CD36 H-score (p = 0.021, HR 1.91), residual disease, and age were significantly and independently associated with overall survival (Table 2). Figure 3 shows the survival curves of patients with positive compared to negative CD36 expression, corrected for clinicopathologic parameters.

Overall survival curves for negative and positive CD36 abundance according to the multiple Cox regression model corrected for age, FIGO stage, residual disease, and bevacizumab treatment (HR 1.91 [1.10–3.31], p = 0.021; x-axis in months; cf. Table 2). The dotted lines show the median survival times of both groups. As these survival curves are derived from a multiple Cox regression model, no censored patients are indicated.

Correlations with molecular characterizations

From previous projects, extensive molecular characterizations of blood, ascites, and tumor samples were available for subpopulations of the patients analyzed in this study.

Multiplexed immunoassays

A Luminex-based assay analyzing 56 cyto- and chemokines revealed significant positive correlations of CD36 abundance with CXCL19, CCL2, CCL3, and Osteopontin in matching serum samples using an FDR cutoff of 0.2 (Table 3, Supplementary Fig. S1).

There was no significant correlation of CD36 abundance with chemokines and cytokines measured in ascites samples (data not shown).

Proteomics

Twenty-one proteins were found to be associated with CD36 abundance in ascites samples (Table 4) using raw p-values and a cutoff of 0.05. Of these, three proteins are functionally annotated to be involved in proliferation/migration (PEBP4, LCN2, CDC42) and three involved in lipid metabolism (LCN2, CFHR1, and CFHR4) (Supplementary Fig. S2). After correction for multiple testing (FDR < 0.2) significancy was no longer present.

Metabolomics

Metabolomics of serum samples revealed 82 metabolites significantly associated with CD 36 abundance using an FDR cut-off of 0.2 (Table 5). These include eight amino acids, which were all negatively correlated: Citrulline, Glutamine, Glycine, Histidine, Lysine, Threonine, Tryptophan, and Tyrosine. Four of these belong to the group of essential amino acids (Histidine, Lysine, Threonine, and Tryptophan). Except for phenylalanine (log2 fold-change 0.078), the other essential amino acids (isoleucine, leucine, methionine, and valine) were all negatively correlated, though not reaching significance.

Contrary to serum, metabolomics analysis of ascites was not significantly associated to CD36 abundance (FDR > 0.2). Though not significant, all essential amino acids were again negatively correlated to CD36 abundance.

Of all significantly correlated glycerophospholipids (GPhL) in serum samples, unsaturated phospholipids were the vast majority (53/60, 88.3%). Those unsaturated phospholipids were all down regulated compared to saturated phospholipids (7/19; 36.8%) (p = 0.001). All significantly deregulates GPhLs can be found in Supplementary Fig. S6.

RNA-sequencing

rRNA-depleted RNA sequencing data from tissue samples were analyzed for significant correlations with CD36 positivity. Using a 0.05 FDR cut-off, 393 genes correlated with CD36 abundance (2,794 if using an FDR cut-off of 0.2), 196 positively and 197 negatively. All vascular-associated genes from the gene ontology (GO)22,23 were extracted (n = 398) and overlapped with the genes significantly associated with CD36 abundance, yielding seven vasculature-associated genes, six upregulated and one downregulated (Table 6).

A signal pathway analysis (SPIA) revealed three activated pathways significantly associated with CD36 abundance: the “VEGF signaling pathway”, “regulation of lipolysis in adipocytes”, and “glutamatergic synapse”. Figures 4, 5 and 6 show these pathways with log2 fold-changes between CD36 positive and CD36 negative patients, representative molecules from each pathway can be found in Supplementary Fig. S3-5.

KEGG pathways “VEGF signaling pathway”, significantly associated with CD36 abundance. Color scale showing up- (red) and down-regulation (green) of affected proteins. Supplementary Figure S4 shows boxplots of different expressions of relevant genes (TSHR, PRKACA, INSR, ADCY6) of this pathway. Images are obtained from KEGG58,59,60.

KEGG pathways “Glutamatergic Synapse”, significantly associated with CD36 abundance. Color scale showing up- (red) and down-regulation (green) of affected proteins. Supplementary Figure S5 shows boxplots of different expressions of relevant genes (GNB5, SLC38A2, PRKACA, PPP3CA) of this pathway. Images are obtained from KEGG58,59,60.

In each two pathways, protein kinase A (PKA) and protein kinase B (PI3K) were found upregulated. The most strongly positively correlated pathway components were thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)-receptor (in the lipolysis pathway), Protein Phosphatase 3 Catalytic Subunit Alpha (PPP3CA, CALN) in the VEGF signaling pathway as well as AMPA (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor) and Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 2B (PP2B) in the glutamatergic synapse pathway. Negatively correlated pathway components were adPLA, PLIN, and COX (components of the insulin signaling pathway) in the lipolysis pathway and SHANK in the glutamatergic synapse pathway.

Projecting the differentially expressed genes between CD36 positive and CD36 negative samples on an ovarian cancer specific planar and scale free small world co-association gene expression network21 revealed one significantly associated cluster of proteins involved in protein translation, i.e. ribosomal proteins, all positively associated with CD36 expression (Fig. 7; cave: all log2 fold-changes shown in the network are positive).

Projection of significantly CD36-associated genes on an ovarian cancer-specific planar and scale-free small world co-association gene expression network revealing proteins involved in protein translation, i.e. ribosomal proteins. All shown proteins are positively correlated with CD36 abundance, the color scale corresponds to the log2 fold-change of the individual genes. Images are obtained from KEGG58,59,60.

Discussion

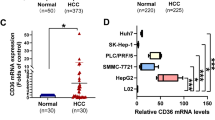

We performed an analysis of CD36 expression in tumor tissues of EOC patients. CD36 expression was predominantly found on tumor vasculature. CD36 positive tumor vasculature was significantly associated with unfavorable overall survival in HGSOC patients, univariately and corrected for known clinicopathologic parameters (age, FIGO stage, residual tumor after debulking, and Bevacizumab treatment) in a multiple Cox regression model. High CD36 expression levels on tumor cells have already been correlated to worse prognosis in brain, cervical, colorectal, gastric, pancreatic, and prostate cancers24.

Until now, CD36 expression in EOC has mainly been investigated on the RNA level and in cell culture models4,17,25.

Immunohistochemical CD36 expression in HGSOC was reported once by Wang et al.18, with CD36 expression on 97% (n = 130/134) of HGSOC tissues on a tissue microarray (TMA) compared to 61% on the ovarian surface epithelium of healthy controls, with particularly high staining intensities on metastatic tissues. They did, however, not investigate the impact of CD36 expression on survival outcomes. The discrepancy of almost missing CD36 expression on tumor cells and the expression pattern observed in tumor vasculature in this study compared to the high CD36 positive expression on tumor cells described by Wang et al. can be explained by the usage of different antibodies: the rabbit polyclonal CD36 antibody (ab78054, Abcam) by Wang et al., and the rabbit polyclonal anti-CD36 HPA002018 antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) in this study. HPA002018 was validated in The Human Protein Atlas (proteinatlas.org)., which also revealed negative expression of CD36 in all EOC tumor samples shown26.

A small number of studies investigated immunohistochemical staining of CD36 in other tumor entities. Hawighorst et al. analyzed tumor development in normal vs. transgenic mice with targeted overexpression of TSP-1 (a ligand for CD36) in the epidermis following a standard two-step chemical skin carcinogenesis model. They found a high expression of CD36 in blood vessels compared to a low expression of CD36 in lymphatic vessels27. Other studies stained CD36 in gastric cancer28, bladder cancer29, and glioblastoma30, but did not discuss CD36 staining of tumor vasculature. One publication by Enke et al. presented an image of CD36 immunohistochemical staining in prostate cancer, where CD36-positive vessels can be assumed, although vessel staining was not discussed31.

Four cytokines were significantly correlated to the CD36 abundance in blood serum using multiplexed cyto- and chemokine assays. Serum CXCL16, a known promoter of peritoneal metastasis, cell invasion and migration in ovarian cancer32,33,34, showed the highest correlation with CD36 abundance. CXCL16 has been associated with highly invasive and aggressive ovarian cancer by increasing the expression and secretion of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) and activation of its receptor CXCR634. Serum CCL3, which was also positively correlated to CD36 abundance, has been associated with tumor progression in colorectal cancer35, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma36, cholangiocarcinoma37, breast cancer, osteosarcoma, leukemia, and multiple myeloma38. Osteopontin, which was also significantly positively correlated to CD36 abundance, is associated with chemoresistance and poor prognosis in ovarian cancer39.

Several analytes were significantly correlated to CD36 expression in proteomics and metabolomics analyses of ascites and blood serum. PZP, which was previously identified as a potential diagnostic biomarker for colorectal cancer and lung adenocarcinoma in type 2 diabetes patients40,41, was positively correlated to CD36 abundance. PZP is elevated in malignant gynecologic diseases, such as ovarian cancer, compared to benign gynecologic diseases42. LCN-2, also positively correlated with CD36 abundance, has antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and anti-stress effects. Additionally, LCN-2 can destroy the extracellular matrix, potentially supporting cancer metastasis43. High mobility group box-B 1 (HMGB1) is expressed by cancer cells and contributes to tumor growth and metastasis and was also positively correlated with CD36 abundance. HMGB1 is associated with chemotherapy resistance in EOC44. In addition, three further proteins were positively correlated to CD36 abundance, PEBP4, LCN2, and CDC42, which are all involved in cell proliferation and migration.

CD36, as a scavenger receptor, binds oxLDL and free FA, which are subsequentially internalized into endothelial cells6,7 and provide i.a. energy for cell metabolism5. The most CD36-associated gene-expression subnetwork (projected onto an HGSOC-specific gene expression co-association network) revealed increased ribosomal activity and protein translation. The transmembrane molecule CXCL16 (see above) also acts as a scavenger receptor for oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL)45.

The majority of GPhLs significantly correlated with CD36 abundance were unsaturated GPhLs and were all negatively correlated to CD36 abundance. Several metabolomic studies described a decrease in lysophosphatidylcholines, which are generated by the cleaving of phosphatidylcholines, in the blood of ovarian cancer patients compared to healthy controls46. We previously showed that low unsaturated serum GPhL concentrations in blood were associated with unfavorable overall survival in EOC patients47. Additionally, osteopontin was significantly negatively correlated with the concentration of unsaturated serum GPhLs47, which fits to the positive correlation with high CD36 expression discovered in this study. High unsaturated serum GPhL concentrations were also positively correlated with histone expression in tumor cells47, while CD36 abundance was negatively correlated to Histones 2 A abundance in this study.

RNA sequencing results from isolated tumor cells revealed the pathway “regulation of lipolysis in adipocytes” as a significantly associated pathway with CD36 abundance. Protein kinase A (PKA), involved in lipid metabolism, was part of two of the three significantly associated pathways and was upregulated in CD36-positive tumors. Furthermore, proteomics analyses of ascites samples revealed three proteins involved in lipid metabolism (LCN2, CFHR1, and CFHR4) significantly correlated with CD36 expression.

Seven amino acids (lysine, glycine, tryptophan, histidine, threonine, glutamine, and tyrosine), thereof four essential amino acids (lysine, tryptophan, histidine, and threonine), were negatively correlated with CD36 expression. Except for phenylalanine, all other essential amino acids (isoleucine, leucine, methionine, and valine) were all negatively correlated, though not reaching significance. Plewa et al. investigated serum-free amino acids in ovarian cancer patients and described twelve amino acids significantly altered in concentrations in ovarian cancer patients compared to healthy controls including borderline tumors48. Decreased histidine levels have previously been reported in ovarian, cervical, and lung cancer49,50,51 patients. Low tryptophan levels have also been reported in ovarian cancer52 and an increased kynurenine to tryptophan ratio has been observed in various tumors, including ovarian cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma, and lung cancer53. Lysine, tryptophan, histidine, and threonine, the negatively correlated essential amino acids, were previously identified as the four amino acids with the highest impact on patient survival in HGSOC47. Furthermore, we previously described that low abundance of essential amino acids in serum correlated with unfavorable overall survival in HGSOC patients47.

A limitation of this study is that due to the retrospective character, sample material was not available from all patients for the omics analyses. Another limitation is the contradictory staining results compared to the study of Wang et al.18, which could be explained by the use of different antibodies26. Our results are consistent with CD36 vessel staining observed by Hawighorst et al.27.

We have not found significant alterations in chemokines, cytokines, or metabolites concerning CD36 in ascites samples, in contrast to serum samples, where significant results were obtained. This could be due to a higher inter-patient variability of ascites (PMID: 34454680) compared to serum with a very tight regulated chemistry. The pathogenesis of ascites is complex and influenced by various aspects and ascites volumes differ vastly between patients, as well as the build-up time or the “incubation” time of ascites spent in the patient until the ascitic fluid was extracted from the patient54,55. Furthermore, while serum can show only traces of all cancer cells in the body, the percentage of cancer cells in malignant ascites is diverse, with single tumor cells and tumor spheroids making up a substantial proportion of cells in ascites56.

Conclusion

We investigated CD36 protein expression in late-stage HGSOC tissue samples whereby expression was observed mainly on tumor vasculature. Positive CD36 tumor vasculature expression was significantly correlated with residual disease after debulking surgery. Furthermore, positive CD36 expression was associated with unfavorable overall survival in patients with advanced HGSOC. In these patients, evidence for an increased tumor metabolism was found, as well as a decrease of metabolic building blocks in peripheral blood (i.e. unsaturated glycerophospholipids and essential amino acids), indicating a higher – presumably CD36-mediated – uptake capacity.

Our study supports the role of CD36 in tumor metabolism, possibly via CD36+-endothelial cell-mediated glycerophospholipid/oxLDL uptake.

Data availability

RNA sequencing data have been submitted to the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and are available under the accession number GSE29364357. Raw ascites proteomics data were already published (see Table S1 in20). Other data presented in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Statistik Austria. Krebserkrankungen in Österreich 2020. Vienna.

Center, G. C. R. Ovarian cancer Survival in Germany: an Nationwide Analysis by Stage and Histotype (Robert Koch-Institut, 2024).

Wang, H. et al. CD36-mediated metabolic adaptation supports regulatory T cell survival and function in tumors. Nat. Immunol. 21 (3), 298–308 (2020).

Ladanyi, A. et al. Adipocyte-induced CD36 expression drives ovarian cancer progression and metastasis. Oncogene 37 (17), 2285–2301 (2018).

Wang, J. & Li, Y. CD36 Tango in cancer: signaling pathways and functions. Theranostics 9 (17), 4893–4908 (2019).

Harmon, C. M. & Abumrad, N. A. Binding of sulfosuccinimidyl fatty acids to adipocyte membrane proteins: isolation and amino-terminal sequence of an 88-kD protein implicated in transport of long-chain fatty acids. J. Membr. Biol. 133 (1), 43–49 (1993).

Pi, X., Xie, L. & Patterson, C. Emerging roles of vascular endothelium in metabolic homeostasis. Circul. Res. 123 (4), 477–494 (2018).

Hanahan, D. & Weinberg, R. A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144 (5), 646–674 (2011).

Kimmelman, A. C. & Sherman, M. H. The role of stroma in Cancer metabolism. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Med. ;14(5). (2024).

Nieman, K. M. et al. Adipocytes promote ovarian cancer metastasis and provide energy for rapid tumor growth. Nat. Med. 17 (11), 1498–1503 (2011).

Yang, L. et al. Targeting stromal glutamine synthetase in tumors disrupts tumor Microenvironment-Regulated Cancer cell growth. Cell. Metab. 24 (5), 685–700 (2016).

Li, W. et al. TGFbeta1 in fibroblasts-derived exosomes promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition of ovarian cancer cells. Oncotarget 8 (56), 96035–96047 (2017).

Zhang, F. et al. Cancer associated fibroblasts and metabolic reprogramming: unraveling the intricate crosstalk in tumor evolution. J. Hematol. Oncol. 17 (1), 80 (2024).

Salimian Rizi, B. et al. Nitric oxide mediates metabolic coupling of omentum-derived adipose stroma to ovarian and endometrial cancer cells. Cancer Res. 75 (2), 456–471 (2015).

Pascual, G. et al. Targeting metastasis-initiating cells through the fatty acid receptor CD36. Nature 541 (7635), 41–45 (2017).

Rachidi, S. M., Qin, T., Sun, S., Zheng, W. J. & Li, Z. Molecular profiling of multiple human cancers defines an inflammatory cancer-associated molecular pattern and uncovers KPNA2 as a uniform poor prognostic cancer marker. PloS One. 8 (3), e57911 (2013).

Westergaard, M. C. W. et al. Changes in the tumor immune microenvironment during disease progression in patients with ovarian Cancer. Cancers ;12(12). (2020).

Wang, S. et al. Development of a prosaposin-derived therapeutic Cyclic peptide that targets ovarian cancer via the tumor microenvironment. Sci. Transl. Med. 8 (329), 329ra34 (2016).

Auer, K. et al. Role of the immune system in the peritoneal tumor spread of high grade serous ovarian cancer. Oncotarget 7 (38), 61336–61354 (2016).

Muqaku, B. et al. Neutrophil extracellular trap formation correlates with favorable overall survival in high grade ovarian Cancer. Cancers ;12(2). (2020).

Bekos, C. et al. NECTIN4 (PVRL4) as Putative Therapeutic Target for a Specific Subtype of High Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer-An Integrative Multi-Omics Approach. Cancers. ;11(5). (2019).

Ashburner, M. et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The gene ontology consortium. Nat. Genet. 25 (1), 25–29 (2000).

Gene Ontology, C. et al. The gene ontology knowledgebase in 2023. Genetics ;224(1). (2023).

Feng, W. W., Zuppe, H. T. & Kurokawa, M. The role of CD36 in Cancer progression and its value as a therapeutic target. Cells ;12(12). (2023).

Baczewska, M. et al. Energy substrate transporters in High-Grade ovarian cancer: gene expression and clinical implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(16). (2022).

Uhlen, M. et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 347 (6220), 1260419 (2015).

Hawighorst, T. et al. Thrombospondin-1 selectively inhibits early-stage carcinogenesis and angiogenesis but not tumor lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic metastasis in Transgenic mice. Oncogene 21 (52), 7945–7956 (2002).

Pan, J. et al. CD36 mediates palmitate acid-induced metastasis of gastric cancer via AKT/GSK-3beta/beta-catenin pathway. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 38 (1), 52 (2019).

Pardo, J. C. et al. Prognostic impact of CD36 immunohistochemical expression in patients with Muscle-Invasive bladder Cancer treated with cystectomy and adjuvant chemotherapy. J. Clin. Med. ;11(3). (2022).

Hale, J. S. et al. Cancer stem cell-specific scavenger receptor CD36 drives glioblastoma progression. Stem Cells. 32 (7), 1746–1758 (2014).

Enke, J. S. et al. SARIFA as a new histopathological biomarker is associated with adverse clinicopathological characteristics, tumor-promoting fatty-acid metabolism, and might predict a metastatic pattern in pT3a prostate cancer. BMC Cancer. 24 (1), 65 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Fibrosis of mesothelial cell-induced peritoneal implantation of ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Manage. Res. 10, 6641–6647 (2018).

Hong, L., Wang, S., Li, W., Wu, D. & Chen, W. Tumor-associated macrophages promote the metastasis of ovarian carcinoma cells by enhancing CXCL16/CXCR6 expression. Pathol. Res. Pract. 214 (9), 1345–1351 (2018).

Mir, H. et al. Higher CXCL16 exodomain is associated with aggressive ovarian cancer and promotes the disease by CXCR6 activation and MMP modulation. Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 2527 (2019).

Ma, X. et al. CCL3 Promotes Proliferation of Colorectal Cancer Related with TRAF6/NF-kappaB Molecular Pathway. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging. 2387192 (2022).

Kodama, T. et al. CCL3-CCR5 axis contributes to progression of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by promoting cell migration and invasion via Akt and ERK pathways. Lab. Invest. 100 (9), 1140–1157 (2020).

Zhou, S. et al. CCL3 secreted by hepatocytes promotes the metastasis of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma by VIRMA-mediated N6-methyladenosine (m(6)A) modification. J. Translational Med. 21 (1), 43 (2023).

Korbecki, J., Grochans, S., Gutowska, I., Barczak, K. & Baranowska-Bosiacka, I. CC chemokines in a tumor: A review of Pro-Cancer and Anti-Cancer properties of receptors CCR5, CCR6, CCR7, CCR8, CCR9, and CCR10 ligands. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21(20). (2020).

Qian, J. et al. Cancer-associated mesothelial cells promote ovarian cancer chemoresistance through paracrine osteopontin signaling. J. Clin. Investig. 131(16). (2021).

Yang, J. et al. A novel diagnostic biomarker, PZP, for detecting colorectal Cancer in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients identified by Serum-Based mass spectrometry. Front. Mol. Biosci. 8, 736272 (2021).

Yang, J. et al. Discovery and validation of PZP as a novel serum biomarker for screening lung adenocarcinoma in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Cancer Cell Int. 21 (1), 162 (2021).

Teng, H., Zhang, W. Y. & Zhu, F. Q. A study on the serum pregnancy zone protein levels in pregnant women and patients with gynecological tumors. Chin. Med. J. 107 (12), 910–914 (1994).

Jaberi, S. A. et al. Lipocalin-2: structure, function, distribution and role in metabolic disorders. Biomed. Pharmacother. 142, 112002 (2021).

Camara-Quilez, M. et al. The HMGB1-2 ovarian Cancer interactome. The role of HMGB proteins and their interacting partners MIEN1 and NOP53 in ovary Cancer and Drug-Response. Cancers ;12(9). (2020).

Gutwein, P. et al. CXCL16 is expressed in podocytes and acts as a scavenger receptor for oxidized low-density lipoprotein. Am. J. Pathol. 174 (6), 2061–2072 (2009).

Saorin, A., Di Gregorio, E., Miolo, G., Steffan, A. & Corona, G. Emerging role of metabolomics in ovarian Cancer diagnosis. Metabolites ;10(10). (2020).

Bachmayr-Heyda, A. et al. Integrative systemic and local metabolomics with impact on survival in High-Grade serous ovarian Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 23 (8), 2081–2092 (2017).

Plewa, S. et al. Usefulness of amino acid profiling in ovarian Cancer screening with special emphasis on their role in cancerogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. ;18(12). (2017).

Zhang, T. et al. Identification of potential biomarkers for ovarian cancer by urinary metabolomic profiling. J. Proteome Res. 12 (1), 505–512 (2013).

Hasim, A. et al. Plasma-free amino acid profiling of cervical cancer and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia patients and its application for early detection. Mol. Biol. Rep. 40 (10), 5853–5859 (2013).

Klupczynska, A. et al. Evaluation of serum amino acid profiles’ utility in non-small cell lung cancer detection in Polish population. Lung cancer. 100, 71–76 (2016).

Zhang, T. et al. Discrimination between malignant and benign ovarian tumors by plasma metabolomic profiling using ultra performance liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. Clin. Chim. Acta. 413 (9–10), 861–868 (2012).

Lieu, E. L., Nguyen, T., Rhyne, S. & Kim, J. Amino acids in cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 52 (1), 15–30 (2020).

Ford, C. E., Werner, B., Hacker, N. F. & Warton, K. The untapped potential of Ascites in ovarian cancer research and treatment. Br. J. Cancer. 123 (1), 9–16 (2020).

Kipps, E., Tan, D. S. & Kaye, S. B. Meeting the challenge of Ascites in ovarian cancer: new avenues for therapy and research. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 13 (4), 273–282 (2013).

Capellero, S. et al. Ovarian Cancer cells in Ascites form aggregates that display a hybrid Epithelial-Mesenchymal phenotype and allows survival and proliferation of metastasizing cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. ;23(2). (2022).

Auer, K. et al. Peritoneal tumor spread in serous ovarian cancer-epithelial mesenchymal status and outcome. Oncotarget 6 (19), 17261–17275 (2015).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28 (1), 27–30 (2000).

Kanehisa, M. Toward Understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28 (11), 1947–1951 (2019).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53 (D1), D672–D7 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Core Facility Imaging of the Medical University of Vienna for their support.

Funding

Funding by the Austrian Research Promotion Agency FFG: BRIDGE project ‘DECIMA’ (project no. 880603) and the City of Vienna Fund for Innovative Interdisciplinary Cancer Research (project no. 21021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.T.G., S.A. and D.P. designed the study, C.T.G., S.A., G.H., L.H., C.G., S.P. provided clinical samples and clinical information, C.T.G., E.U. and L.H. performed the experiments/IHC analyses, C.T.G. and G.H. performed IHC assessment, D.P. did the bioinformatics, C.T.G. and D.P. drafted the manuscript, and all revised and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Medical University of Vienna (1966/2020 and 1892/2021). All patients gave their written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grech, C.T., Aust, S., Hofstetter, G. et al. High CD36 expression in the tumor microenvironmental vasculature correlates with unfavorable overall survival in high grade serous ovarian cancer. Sci Rep 15, 19354 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01917-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01917-z