Abstract

Health professionals (HPs) who work on the front lines are more likely to contract COVID-19.Healthmanners of HPs impact control and prevention activities employed in answer to the contagion crisis. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to assess the pooled level of practice and associated factors toward COVID-19 prevention among HPs in Ethiopia. PubMed, Scoups, Web of Science, Google Scholar (search engine), Google Advance, and Cochrane Library were searched from December 20, 2023 -January 30, 2024. Data was dugout using Microsoft Excel (version 10) and analysis was computed using STATA version 11. Funnel plot and quantitatively further through Egger’s regression test, with P < 0.05 was used to check publication bias. I2 statistics were used to check the heterogeneity of the studies. Pooled analysis was used using a weighted inverse variance random-effects model. A subgroup analysis was conducted based on publication year and region. Meta-regression and sensitivity analysis were used. Eighteen studies with 7,775 Health professionals were included in the review process. Among them, 57.03% (95% CI; 48.41, 65.65%) of HPs practice correctly. Although the risk factors reported were inconsistent between studies, access to infection prevention training (IP) (AOR = 1.79; 95% CI 1.54, 2.08), good knowledge (AOR = 1.92; 95% CI 1.38, 2.66), MSc degree and above (AOR = 3.53; 95% CI 2.64, 4.71), and positive attitude (AOR = 2.19; 95% CI 1.50, 3.19) were significant predictors of good practice. Nearly 43% of health professionals had poor practice. Good knowledge, positive attitude, level of education, and infection prevention training were the main determinants of good practice. The responsible authorities do emphases to halt barriers and improving the zero infection principles of health professionals during the pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A novel coronavirus infection, 2019 (COVID-19), was initially discovered in China and World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19, as a pandemic disease on March 20201,2.

On February 01, 2024 the virus affected more than 231 nations across the globe and it was expected that over 760,000,000 people were contracted with COVID-19 worldwide; more than 7 million have lost their precious lives6. In Ethiopia more than 501 million cases and 7,574 deaths from recent data6. As of June 20, 2023, almost 13 billion COVID-19 vaccination doses had been administered globally3. The risk of hospitalization and mortality from COVID-19 was 7.2 and 3.9 times higher in individuals who had not received the vaccination than in those who had received at least one booster dose7. Worldwide coronavirus diseases had numerous negative consequences such as disrupting the health service system, overwhelming (social, political, psychological), economic crises, and loss of productivity8,9,10,11. This impact is more than triple with the existing limited resources in underdeveloped countries like Ethiopia12,13.The cornerstone of health systems and the engine for attaining universal health coverage and global health security are health professionals. But numerous healthcare providers got an infection and many of them died14. There is no comprehensive, global database that counts the number of nurses and other healthcare workers who have the disease or died from it15. WHO reports 80, 000 to 180, 000 healthcare professionals may have perished from COVID-19 between January 2020 and May 202117. International Council of Nursing (ICN) reports that more than 230,000 medical personnel worldwide have contracted the disease, and 600 nurses have already lost their lives to the virus16. Different studies show15–57.06% of HCWs was infected with COVID-1918,19. A systematic review showed that 11% of HPs were contracted by COVID-19 of which 48% were nurses20.

All healthcare providers indeed ought to follow sound preventative and control procedures; however, research employed around the globe revealed that a substantial number of healthcare workers had inadequate practice in the prevention of COVID-19 infection. In Chicago and Pakistan,90%27 and 74.1%28 of healthcare professionals had poor practice of donning and doffing PPE, respectively. In India, Lebanon and Nepal 54.8%29, 50.3%30, and 24.4%31 of HPs had poor practice of COVID-19 prevention, respectively. Likewise in Nigeria and South Africa, 40% and 37% of healthcare workers had poor practice of Covid-19 prevention. Furthermore, in Amhara and South Nation Nationality of Peoples (SNNPs) Region73%32 and 64.5%33 of HPs had inadequate practice of COVID-19 control measures, respectively. Inadequate practice causes delays in diagnosis and treatment, as well as poor adherence to treatment guidelines, all of which contribute to the spread of COVID-1934,35.

Numerous studies in different parts of the world highlight that knowledge, attitude, age, work experience, sex, type of healthcare facilities, standard precaution training, availability of infection prevention guideline, profession of healthcare workers, source of information, level of education, and personal protective equipment were significant factors of practice to wards COVID-19 prevention30,36,37,38. However; there are inconsistent findings of health professionals practice and factors towards COVID-19 control measures. As far as our knowledge, no published research has been done to evaluate the pooled estimate of practice and its associated factors of COVID-19 prevention among health professionals. Across the world, different scholars explore the factors that contribute to HPs' infection, such as inaccessibility of infection prevention training, unavailability of personal protective equipment (PPE), lack of understanding of the disease, unclear diagnostic criteria, and absence of diagnostic tests, psychological stress, depression, and burnout15,16,19,21,22,23,24,25,26. Our finding provides insight for policymakers, programmers, decision- makers, and federal health office ministers to save the precious life of healthcare workers and to enhance health service management. Therefore, these systematic reviews and meta-analysis aimed to assess the pooled level of practice and associated factors of COVID-19 prevention among health professionals in Ethiopia.

Methods

Setting and study design

Ethiopia is one of the second most populous and underdeveloped countries located in the Horn of Africa. It currently has 115 million population with a projected population of 133.5 million in 2032 and 171.8 million in 205039.The Ethiopian health system is structured into three levels. These are tertiary level health care (i.e. specialized hospital services with the capacity to treat 3.5 to 5.0 million people), secondary level health care (i.e. general hospitals, which treat 1 to 1.5 million people), and primary care services (for example, primary hospitals, which serve 60,000 to 100,000 people) and health centers (which serve 40,000 people)40.The primary health care services are mainly focused on disease prevention.

A systematic review and meta-analysis were used to summarize the level of preventive practice of the COVID-19 pandemic among health professionals in Ethiopia. The preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis guideline (Updated PRISMA 2020 statement checklist) were used for this review (Supplementary file 1: Table S1)41.

Search strategy

The updated PRISMA 2020 statement guideline, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Statement42 was used to report the results of this systematic review and meta-analysis. To obtain the significant articles that fit the study objectives, international electronic databases such as PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus, Web of Science, Cochrane Library and a list of references were used from December 10, 2023 to January 30, 2024. Furthermore, experts in the field were consulted to obtain unpublished articles, and the bibliography of selected articles was reviewed for additional relevant studies. Two independent authors conducted the article search process independently and systematically. Moreover, by cross-referencing, other noteworthy publications were manually extracted from the grey literature. The core search terms and phrases were ‘health professional’, ‘health worker’, ‘COVID-19 preventive measures’, ‘COVID-19’, ‘health worker practice’, ‘COVID-19 magnitude preventive practice’, ‘associated factors’, and ‘Ethiopia’. Search strategies were developed using different Boolean operators. In particular, to fit the advanced PubMed database, the following search strategy was applied: “health personnel” [MeSH Terms] OR healthcare workers OR “health professional” [MeSH Terms] AND (COVID-19 preventive practice [MeSH Terms] OR COVID-19 preventive practices) AND (Associated factors) AND ((Ethiopia)] or (((((((Prevalence of COVID-19 preventive practice) OR (control measures)) OR (SARAS-2)) OR (COVID-19 infection)) AND (health professionals)) OR (healthcare providers)) OR (health care workers)) AND (Ethiopia) see the search strategy syntax table (Table S2).

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Only those studies that fulfilled the following requirements were included in this systematic review:1 all observational quantitative studies that reported the prevalence of COVID-19 preventive practice and its associated factors from January 2020 to December 30, 20232, Participants who are health professionals working in Ethiopia. Health professionals were defined as all people engaged in activities whose primary intention is to improve health3, studies that reported the proportion of practice on COVID19 preventive measures and its associated factors4, studies that were conducted in Ethiopia5, this study included only published articles in English-language.

Exclusion criteria

Qualitative study design, single case study research reports, study protocols, reviews, and citations lacking the entire text, program evaluation studies, letter to editors not fully accessed articles, poor methodological quality, articles on general population, no clear report, unpublished studies, not written in English and outside of the study area were excluded.

Study selection process

To remove duplicate studies, the obtained articles were exported to reference management software, Endnote version 7. Two authors (Almaz Tefera Gonete and Berhan Tekeba) screened and evaluated the titles and abstracts of the studies, followed by full-text assessments independently and systematically. Disagreements were resolved by consensus and discussion if not resolved referred to third author and decision made. Eligible studies were independently selected and evaluated by two authors ensuring the predefined criterion.

Exposure variables

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, associated factors (accessibility of infection prevention training, availability of infection prevention guidelines, having chronic illness, sex and level of education, type of health service, source of information, availability of protective personal equipment, level of knowledge and attitude) that increase the probability of good practice of health professionals were taken into account as exposure variables to calculate the magnitude of good practice of health professionals toward COVID-19 preventive practice.

Outcome variable

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, the pooled level of preventive practice of COVID-19 was considered the outcome variable for this study.

Quality assessment of studies

Articles examined in the database were collected and identical articles were manually deleted using EndNote version X7.Two assessors (ATG and BT) independently evaluated the superiority of the included studies using the JBI checklist43 established for methodological quality assessment of prevalence studies that includes criteria of inclusion, description of subjects and setting, reliability, and validity of exposure measurement, criteria of measurement, identification, and strategies to deal with confounding factors, validity, and reliability of outcomes measurement, and statistical analysis used. Studies were scored on a scale of 0 to 1 for eight items and studies with a total score of < 4, 4–6,and 7 to 8 were considered to have low, moderate, and high methodological quality, respectively. Any disagreements in ratings of the studies were resolved through discussion between the two reviewers.

Extraction of data

From Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI), A standardized data extraction tool was adapted and used to extract data from articles included in the review43. Two groups of review authors, group one (ATG and BT) and group two (ATG and TTT), extracted the data independently after a screening of titles, abstracts, and full texts of each primary study included in this meta-analysis. In cases where there were differences between the two authors of the group on the extracted data, the differences were resolved through discussion. Any variance between the two authors of the group was referred to the third author of the group (BSW and MSA) and resolved by consensus after discussion. The following necessary information was extracted from each included article: the name of the first author, study setting, year of publication, study design, study participants, sample size, and percentage of good level of practice among HPs towards COVID-19 pandemic. The data was recorded in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. When the authors found multiple publications from the same dataset, the articles reported the prevalence and factors associated with a good level of practice in extractable form were included. Data extraction incorporates primary author, region, and publication year, prevalence with a 95% confidence interval, study design, sample size, sampling technique, odd ratio or relative risk, and quality score of each study. Data from eligible studies were extracted and organized into data tables (Table 1).

Heterogeneity and publication bias

I2 statistics were used to determine the percentage of overall variation between studies that resulted from heterogeneity44. Therefore, the values of I 2, 75%, 50%, and 25% represented high, moderate, and low heterogeneity, respectively. In the same way, a p-value less than 0.05 were used to declare heterogeneity. For the test result that indicates the presence of heterogeneity, a random effect model was used as the analysis method as it reduces the heterogeneity of studies45. Visual examination of funnel plot asymmetry, Begg-Mazumdar rank correlation tests, and Egger regression tests were also used to check for publication bias46. Moreover, fill and trim analysis followed Egger’s and Begg’s test with a p-value less than 0.05 to evaluate the presence of publication bias47.

Sensitivity analysis

Furthermore, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to see the effect of a single study on the overall estimation.

Data processing and statistical analysis

Data were extracted in Microsoft Excel (version10) format and exported to STATA (version 11) software for analysis. The random effect model was used to assess the pooled prevalence and associated factors of COVID-19 preventive measures among healthcare professionals for the adjustment of the observed variability48. The pooled effect size with a 95% confidence interval was present using a forest plot graph and used to visualize the presence of heterogeneity graphically49. For the possible difference in the primary study, we explored subgroup analysis and meta-regression subsequently using publication year, study setting, sample size, and region. For the second outcome, the odds ratio was used to determine the association between determinant factors and outcome variables in the included articles.

Results

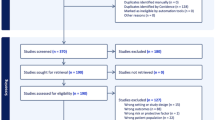

A total of 2,472 articles reporting the prevalence of COVID-19 preventive practice and associated factors of health professionals in Ethiopia were searched using previously stated databases. Of the total of research articles, 450 were excluded due to duplications. After reviewing the titles and abstracts, about 1890 research papers were excluded because they were irrelevant. An article was omitted due to the poor quality of the study (114). Lastly, 18 full articles were involved in this systematic review (Fig. 1).

Description of included studies

All researched articles included in this systematic review were conducted by a cross-sectional study design and published from 2020 to 2022. Eighteen articles with 7,775 study participants were included to assess the pooled level of good practice of COVID − 19 prevention of health professionals. The included studies showed that the lowest prevalence (38.7%)50, and highest (84.9%)51 Covid-19 preventive measures of health professionals were from Amhara region and Addis Ababa, respectively. This review includes five studies from the Amhara region 28%50,52,53,54,55, two studies from Tigray 11%24,56, three studies from the Oromia region 16.6%57,58,59, four studies from SNNPs 22%33,60,61,62, two studies from Addis Ababa 11%51,63, and another two studies from National 11%64,65 (Table 1).

The pooled level of health professionals’ practice towards COVID-19 prevention in Ethiopia

The pooled status using the fixed effect model confirmed significant heterogeneity among the included studies. Using the Dersimonian-Laird random effect model, the estimated status of practice on COVID- 19 prevention reported was 57.03% (95% CI (48.41%, 65. 65%) (Fig. 2).

Publication bias and heterogeneity of included studies

The inverted funnel plot is symmetrically distributed; concluded that has no publication bias as shown (Fig. 3). Hence, four studies lay on the right side, four studies on the left side of the line, and 10 studies lay on the center representing the estimated status. The overall heterogeneity of the included studies was Ι2 = 98.6%, with P < 0.0001 by using the random effect model to adjust the observed variability (Fig. 2). The Begg’s and Egger’s tests were performed with p = 0.015 indicating the existence of publication bias. Moreover, filled funnel trim analysis was performed to further investigate publication bias, and no studies were observed beyond the limit (Fig. S1).

Subgroup analysis

The subgroup analysis was executed based on the region, publication year, sampling technique, and data collection methods. The analysis outcome showed that the source of heterogeneity is not due to region. The lowest good practice among health professionals was identified in National studies at 54.35% (95% CI 28.77–79.93) and the highest was in Tigray at 65.70% (95% CI (62.44–68.95) (Table 2). The source of heterogeneity was further evaluated using study year, sampling technique, or study setting to identify the reason for variation between studies, but none of them is the source of heterogeneity (Table 2).

Meta-regression

Moreover, of the subgroup analysis, univariate meta-regression is carried out with sample size, publication year, and region and sample technique for possible heterogeneity. The result of the analysis indicates that none of them significantly affected heterogeneity between studies (Table 3).

Sensitivity analysis

However, the analysis result of the sensitivity test using the random effects model indicated that no single study affected the overall estimate because of all variables lie on the estimated line the line between lower class limit and upper class limit (Fig. S2).

Associated predictors of practice among HPs towards the COVID-19 pandemic

In the random effect model, the pooled effect size of good practice among HPs who had IP training was 1.79 times greater than those HPs who had no IP training (AOR = 1.79; 95% CI:1.54, 2.08) (Fig. 4).

Heterogeneity and publication bias of included studies for access to IP training

As stated, Fig. 4 showed that the overall heterogeneity test (I2) on the effect of accessibility of IP training was 21.4% with a p-value of 0.273, using a random-effects model to adjust the observed variability. This heterogeneity test indicates that there is no observed variability among the included studies.

Concerning publication bias, the graph asymmetry test of the funnel plot shows a symmetric distribution, with three lay on the right side and three laying on the left side (Fig.S3), but objectively Egger’s test p-value = 0.048, indicating that there is publication bias.

Likewise, the odds of being knowledgeable increase the level of good practice among HPs nearly 2 times more than their counterpart parts (AOR = 1.92; 95% CI: 1.38, 2.66) (Fig. 5).

Heterogeneity and publication bias of the included studies for good knowledge.

As stated in Fig. 5, the overall heterogeneity test (I2) on the effect of being knowledgeable was 80.2% with a value of p = 0.000, using the random effect model to adjust the observed variability. This heterogeneity test indicates that there is observed variability in the included studies.

Relating to publication bias, the graphic asymmetry test of the funnel plot shows a slightly asymmetrical distribution, with one lay on the right side and eight lay on the left side (Fig. S4), but objectively the Egger test p-value = 0.074, indicating that there is no publication bias.

Correspondingly in the random effect model, the pooled effect size of good practice among HPs who had a favorable attitude had 2.19 times superior practice of COVID-19 prevention when compared to HPs who had unfavorable attitude towards COVID-19 preventive practice (AOR = 2.19; 95% CI:1.50, 3.19) (Fig. 6).

Heterogeneity and Publication bias of included studies for positive attitude as stated in Fig. 6, the overall heterogeneity test (I2) on the effect of positive attitude was 68.7% with a P-value of 0.012, using a random effect model to adjust the observed variability. This heterogeneity test indicates that there is observed variability in the included studies.

Despite publication bias, the graphic asymmetry test of the funnel plot shows an asymmetrical distribution, two on the right side and five on the left side (Fig. S5), and objectively Egger’s test p-value = 0.000, indicating that there is publication bias. Furthermore, HPs with a degree of MSc. and greater than 3.53 times are more likely to have a good level of practice compared to those without a degree of M.Sc. and greater (AOR = 3.53; 95%CI: 2.64, 4.71) (Fig. 7).

Heterogeneity and Publication bias of the included studies for MSc degree and above.

As stated in Fig. 7, the total heterogeneity test (I2) on the effect of having MSc degree and above was 91.9% with a P-value of 0.000, using the random effect model to adjust the observed variability. This heterogeneity test indicates that there is observed variability in the included studies.

About publication bias, the funnel plot graphic asymmetry test illustrates little asymmetrical distribution, as three lay on the right side, five lay on the left side, and one on the center (Fig. S6), nonetheless objectively Egger’s test p-value = 0.265, indicating that there is no publication bias.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis determine the estimated status of practice and its associated factors of HP on the prevention of coronavirus infection. It is a contagious pandemic and a major global burden, including Ethiopia. Controlling the spread of the viruses is a serious issue around the world. Estimating the pooled level of satisfactory practice towards COVID-19 prevention in Ethiopia can contribute to informing HPs, healthcare organizations, researchers, programmers, and policymakers to halt the spread of pandemic infections or out-breaks, implement interventions, implement early mitigation strategies and fill literature gaps36,66,67,68.

Our result showed that the pooled level of good practice of COVID-19 prevention among HPs was 57.03% (95% CI (48.4%, 65.65%). This finding is in line with a study done in Nigeria 50.8%69,a study conducted in Ethiopia on compliance of health care workers to wards COVID-19 preventive measures and COVID-19 preventive practice among general population which were 49.7 and 51.61% respectively. However, our finding is lower than a global systematic review which was 79.8%36. The reason could be: Most included studies were carried out in developed countries, allowing easy access to online training, up-to-date information related to COVID-19 preventive practice, and availability of PPE, disinfectants such as alcohol or sanitizer. But in underdeveloped countries such as Ethiopia there is a shortage of PPE and disinfectants, a lack of updated information, hard to get continuous and periodic infection prevention training61, due to this in Africa there is bad practice70. Similarly, this finding is greater than a report from a systematic review 44% of the participants had good practice71. The difference could be attributable to the population &sample size difference besides, variation in addition to the variation in the study time. Moreover, our finding is also lower than astudie emploeed in Ethiopia among general population the reason could be the difference in time, study population.

The likelihood of good practice is almost two times increased among HPs who had good knowledge.Ourresultisconsistentwithglobalstudy36, Iran72, Pakistan73, Uganda38, and Ethiopia74. Knowledge is a prerequisite for endorsing preventive practice to fight against the pandemic75. Knowledge is the instrument to establish prevention beliefs, develop positive attitudes, and encourage positive behavior; all contribute to the effectiveness of COVID-19 prevention practice among healthcare professionals29. HPs who have adequate knowledge can find and use evidence-based updated information about ways of transmission, diagnosis, and adhere to the treatment guidelines which enhance precaution measures30. HPs with good knowledge of COVID-19 prevention expected to have expertise in disease transmission informs effective practices such as mask-wearing, appropriate utilization of PPE and social distancing, good community education skills, give standard care for the client, contribute in surveillance and scientific research, participate in global collaboration related to COVID-19 prevention. With the help of these contributions, medical professionals make sure that COVID-19 preventive measures are up to date, contextually appropriate, and always being improved upon, which eventually stops the virus from spreading and safeguards public health.

A positive attitude is found to be a significant predictor of practice toward COVID-19 prevention. Therefore, HPs who had positive attitudes had two times good practice compared to their counterparts. There are findings similar with this result in Nepal76, Saudi Arabia77,78,Pakistan73,Bangladesh79, Ethiopia33 and Uganda80. Good knowledge with a favorite attitude can ultimately promote preventive or positive behavior. Favorite attitude is essential to ensure that protocols are followed and that patient safety is upheld in hospital environments, all of which have the effect of adhering to the treatment guide lines, dis-proofing misinformation and myths about COVID-1950. This is crucial for protecting marginalized populations and ultimately saving lives. Health professionals are more likely to implement these facts if they are aware of the pandemic and have a positive attitude toward taking precautions33. Generally speaking, the optimistic outlook of a health professional serves as a foundation for learning about the pandemic from many sources and relevant bodies to increase knowledge, reason for behavioral changes, and establish good practice.

Moreover, HPs’ positive attitudes on COVID-19 prevention have a critical role in influencing public behavior and the overall efficacy of preventive efforts. Definitely positive attitudes of health professionals significantly influence the public’s behavior towards COVID-19 prevention by serving as role models, providing sound information, increasing patient education and communication, building trust, supporting public health measures, persuading policy, raising innovation, reducing stigma, ensuring continuous learning, improving workplace safety, and engaging in community outreach. These factors cooperatively contribute to a more effective and pervasive adoption of preventive practices. In other words, attitudes influence behavior through cognitive, emotional, and motivational processes, influencing information interpretation, intentions, and decision-making. They align with self-identity and reinforce desired outcomes.

Health professionals who had access to infection prevention training practice correctly twofold over their counterparts. This is consistent with studies employed in Ethiopia55,74,81, Africa70,South Africa, Bangladesh among health professionals, Nurses, and Doctors79,82,83 respectively, and Nepal76. Training gives crucial knowledge about the virus, including how it spreads, what signs to look for and how to avoid it. People who have this knowledge are better able to prevent themselves, and others from getting infected and spreading the virus52. HPs who are trained are better able to manage the difficulties presented by the epidemic and offer individuals afflicted with high-quality care84.Generally IP training plays a pivotal role in improving COVID-19 prevention practices by providing knowledge, skills, and confidence. It leads to improved compliance with health guidelines, lesser infection rates, and enhanced outbreak management. By endorsing consistent and effective infection control measures, training not only helps prevent the spread of COVID-19 but also builds a foundation for handling future public health threats. Consistent & effective training is crucial for continuous improvement professional growth, and overall excellence in practice.

Moreover, HPs who had an MSc degree and above were 3.53 times more likely to have good practice than those who did not have an MSc degree and above. This finding is agreement with studies conducted in India29, Ethiopia53,57,64, global study85, New York City19, and China86.The possible clarification for this finding is the ability of highly educated to easily understand the nature of the disease and easily identify reliable sources of information and an increased opportunity to be exposed to information related to COVID-19 prevention modalities87. More educated health personnel are expected to adhere to treatment guidelines, strictly follow the infection prevention protocol and wisely use PPE50,64. HPs with higher educational success were more likely to have adequate practice on COVID-19 prevention, perhaps due to these HPs’ abilities to find the right source of information, such as published articles and good training programs86. Consequently, it is strongly advised to bridge the practice gap by offering HPs with lower educational qualifications, particularly with specially designed COVID-19 training sessions. Furthermore, professionals with higher educational status may have increased income, leading to the possibility of buying PPE such as a face mask, sanitizer, and alcohol, which may result in better practice toward COVID-19 prevention.

Strength and limitation

Almost all pooled conducted on the first period of coronavirus infection with limited articles, and most studies reported only the descriptive aspects without doing a meta-analysis of or an analysis of contributing factors. However, our study is being done in the post-pandemic period. Likewise, we incorporated the contributing factors of practice towards Covid-19 prevention among HPs to stop the pandemic crisis by working on possible predictors. Furthermore, there is a recommendation from the researcher to assess the practice of HPs to analyze the variations between the early and late stages of the pandemic. Therefore, some limitations must be considered when interpreting the results. First, there was greater heterogeneity among the included studies; therefore, readers should interpret the findings with caution. Second, the included studies used the cross-sectional study design shares the limitation of this, thirdly, our finding was focused on articles published in Ethiopia and in the English language that may not be representative other than the study setting and did not include which was published in other languages.

Conclusion

Almost half of the HPs had poor practice. Accessibility to infection prevention training, good knowledge, a positive attitude, and a high level of education were significantly associated with good practice of COVID-19 prevention. Poor practice leads to delayed diagnosis and treatment and poor infection prevention control. Our finding has numerous implications for HPs, policymakers, and other responsible bodies. It offers a framework to establish interventions targeting predictors to improve the practice of HPs through education, online training programs, and invitations to participate in virtual discussions, as this is a key point to avoid diagnosis delay, disease spread, and poor practice of infection control.

Data availability

Availability of data and materials: The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Corona virus infection disease, 2019

- JBI-MAStARI:

-

Joanna Briggs Institute meta-analysis of statistics assessment and review instrument

- Fig.S:

-

Figure of supplementary files

- ICN:

-

International council of nursing

- IP:

-

Infection prevention

- HP:

-

Health professionals

- LMICs:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- MeSH:

-

Medical subject heading

- PPE:

-

Personal protective equipment

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis

- PubMed:

-

Public/Publisher MEDLINE

- SE:

-

standard error

References

CDC. COVID-19 (2019 Novel Coronavirus) Research Guide 2020. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/library/researchguides/2019NovelCoronavirus.html.

WHO & Coronavirus Officially Declared, A. Pandemic 2020 [cited 2024 1/2]. Available from: https://www.wgbh.org/news/national/2020-03-11/coronavirus-officially-declared-a-pandemic.

WHO. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Key Facts:9 August 2023 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19).

COVID, C. et al. Preliminary estimates of the prevalence of selected underlying health conditions among patients with coronavirus disease 2019—United States, February 12–March 28, 2020. Morbidity Mortali. Weekly Rep.69(13), 382.

Linton, N. M. et al. Incubation period and other epidemiological characteristics of 2019 novel coronavirus infections with right truncation: a statistical analysis of publicly available case data. J. Clin. Med.9 (2), 538 (2020).

Worldmeter Covid-19 Reported Cases and Deaths by Country or Territory Worldwide 2024 [cited 2/2/2024]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/.

Health WSDo. COVID-19 Hospitalizations and Deaths by Vaccination Status in Washington State 2023 [cited 2024 1/2]. Available from: https://doh.wa.gov/sites/default/files/2022-02/421-010-CasesInNotFullyVaccinated.pdf.

Singh, K. et al. Health, psychosocial, and economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with chronic conditions in India: a mixed methods study. BMC Public. Health. 21, 1–15 (2021).

Cerami, C. et al. Covid-19 outbreak in Italy: are we ready for the psychosocial and the economic crisis? Baseline findings from the psycovid study. Front. Psychiatry. 11, 556 (2020).

Bukuluki, P., Mwenyango, H., Katongole, S. P., Sidhva, D. & Palattiyil, G. The socio-economic and psychosocial impact of Covid-19 pandemic on urban refugees in Uganda. Social Sci. Humanit. Open.2 (1), 100045 (2020).

Health UDo, Services, H. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the hospital and outpatient clinician workforce. (2022).

Kluge, H. H. P. et al. Prevention and control of non-communicable diseases in the COVID-19 response. Lancet395 (10238), 1678–1680 (2020).

WHO. COVID-19 significantly impacts health services for noncommunicable diseases 2020 [cited 2024 1/2]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/01-06-2020-covid-19-significantly-impacts-health-services-for-noncommunicable-diseases.

WHO. WHO, Health & Care Worker Deaths during COVID 19 2021. and. Available from: (2021). Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/20-10-2021-health-and-care-worker-deathsduring-covid-19.

Todd, B. The toll of COVID-19 on health care workers remains unknown. Am. J. Nurs. 14–15. (2021).

ICN. ICN. Global Nurses death from Covid-19. Available from: (2020). Available from: https://www.icn.ch/news/more-600-nurses-die-covid-19-worldwide

WHO. Health and Care Worker Deaths during COVID 19. (2021). Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/20-10-2021-health-and-care-worker-deathsduring-covid-19.

Sarah, W. et al. Professional practice for COVID-19 risk reduction among health care workers: a Cross-Sectional study with matched Case-Control comparison. medRxiv. 2021:2021.09. 09.21263315.

Breazzano, M. P. et al. Resident physician exposure to novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV, SARS-CoV-2) within new York City during exponential phase of COVID-19 pandemic: report of the new York City residency program directors COVID-19 research group. MedRxiv 2020:2020.04. 23.20074310.

Gómez-Ochoa, S. A. et al. COVID-19 in health-care workers: a living systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence, risk factors, clinical characteristics, and outcomes. Am. J. Epidemiol.190 (1), 161–175 (2021).

Xing, L. et al. Anxiety and depression in frontline health care workers during the outbreak of Covid-19. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 67 (6), 656–663.https://doi.org/10.1177/002076402096 (2021).

Semaan, A. et al. Voices from the frontline: findings from a thematic analysis of a rapid online global survey of maternal and newborn health professionals facing the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Global Health. 5 (6), e002967 (2020).

Raudenská, J. et al. Occupational burnout syndrome and post-traumatic stress among healthcare professionals during the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol.34 (3), 553–560 (2020).

Gebremeskel, T. G., Kiros, K., Gesesew, H. A. & Ward, P. R. Assessment of knowledge and practices toward COVID-19 prevention among healthcare workers in Tigray, North Ethiopia. Front. Public. Health. 9, 614321 (2021).

Lasalvia, A. et al. The sustained psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers one year after the outbreak—a repeated cross-sectional survey in a tertiary hospital of North-East Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18 (24), 13374 (2021).

Chua, G. T. et al. Multilevel factors affecting healthcare workers’ perceived stress and risk of infection during COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Public. Health. 66, 599408 (2021).

Phan, L. T. et al. Personal protective equipment doffing practices of healthcare workers. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg.16 (8), 575–581 (2019).

Qabool, H., Ali, F., Sukhia, R. H. & Badruddin, N. Compliance to donning and doffing of personal protective equipment among dental healthcare practitioners during the coronavirus pandemic: a quality improvement plan, do, study and act (PDSA) initiative. BMJ Open. Qual.;11(3). (2022).

Maurya, V., Upadhyay, V., Dubey, P., Shukla, S. & Chaturvedi, A. Assessment of front-line healthcare workers’ knowledge, attitude and practice after several months of COVID-19 pandemic. J. Healthc. Qual. Res.37 (1), 20–27 (2022).

Abou-Abbas, L. et al. Knowledge and practice of physicians during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study in Lebanon. BMC Public. Health. 20 (1), 1–9 (2020).

Pandey, S. et al. Knowledge, attitude and reported practice regarding donning and doffing of personal protective equipment among frontline healthcare workers against COVID-19 in Nepal: a cross-sectional study. PLOS Global Public. Health. 1 (11), e0000066 (2021).

Atnafie, S. A., Anteneh, D. A., Yimenu, D. K. & Kifle, Z. D. Assessment of exposure risks to COVID-19 among frontline health care workers in Amhara region, Ethiopia: A cross-sectional survey. Plos One. 16 (4), e0251000 (2021).

Mersha, A. et al. Health professionals practice and associated factors towards precautionary measures for COVID-19 pandemic in public health facilities of Gamo zone, Southern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Plos One. 16 (3), e0248272 (2021).

Abdulrahman Yusuf, K., Isa, S. M., Al-Abdullah, A. F. & AlHakeem, H. A. Assessment of knowledge, accessibility, and adherence to the use of personal protective equipment and standard preventive practices among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Public. Health Res.12 (2), 22799036231180999 (2023).

Doos, D. et al. The dangers of reused personal protective equipment: healthcare workers and workstation contamination. J. Hosp. Infect.127, 59–68 (2022).

Tegegne, G. T. et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of healthcare providers toward novel coronavirus 19 during the first months of the pandemic: a systematic review. Front. Public. Health. 9, 606666 (2021).

Kamabu, L. K. et al. Determinants of knowledge, attitudes, and practices of frontline health workers during the first wave of COVID-19 in Africa: A multicenter online Cross-Sectional study. Infect. Drug Resist.4595, 610 (2022).

Olum, R., Chekwech, G., Wekha, G., Nassozi, D. R. & Bongomin, F. Coronavirus disease-2019: knowledge, attitude, and practices of health care workers at Makerere university teaching hospitals, Uganda. Front. Public. Health. 8, 181 (2020).

Bekele, A. & Lakew, Y. Projecting Ethiopian demographics from 2012–2050 using the spectrum suite of models. Ethiop. Public. Health Assoc.;4. (2014).

Croke, K. The origins of Ethiopia’s primary health care expansion: the politics of state Building and health system strengthening. Health Policy Plann.35 (10), 1318–1327 (2020).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg.88, 105906 (2021).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj;372. (2021).

Peters, M. D. et al. The Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual 2015: methodology for JBI scoping reviews. (2015).

Huedo-Medina, T. B., Sánchez-Meca, J., Marín-Martínez, F. & Botella, J. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I² index? Psychol. Methods. 11 (2), 193 (2006).

Higgins, J. P., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J. & Altman, D. G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Bmj327 (7414), 557–560 (2003).

Rücker, G., Schwarzer, G. & Carpenter, J. Arcsine test for publication bias in meta-analyses with binary outcomes. Stat. Med.27 (5), 746–763 (2008).

Begg, C. B. & Mazumdar, M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1088 – 101. (1994).

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. & Rothstein, H. R. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random‐effects models for meta‐analysis. Res. Synthesis Methods. 1 (2), 97–111 (2010).

Rücker, G., Schwarzer, G., Carpenter, J. R. & Schumacher, M. Undue reliance on I 2 in assessing heterogeneity May mislead. BMC Med. Res. Methodol.8 (1), 79 (2008).

Kassie, B. A., Adane, A., Abebe Kassahun, E., Ayele, A. S. & Kassahun Belew, A. Poor COVID-19 preventive practice among healthcare workers in Northwest Ethiopia, 2020. Adv. Public. Health. 2020, 1–7 (2020).

Deressa, W., Worku, A., Abebe, W., Gizaw, M. & Amogne, W. Risk perceptions and preventive practices of COVID-19 among healthcare professionals in public hospitals in addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PloS One. 16 (6), e0242471 (2021).

Asemahagn, M. A. Factors determining the knowledge and prevention practice of healthcare workers towards COVID-19 in Amhara region, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional survey. Trop. Med. Health. 48 (1), 1–11 (2020).

Bitew, G., Sharew, M. & Belsti, Y. Factors associated with knowledge, attitude, and practice of COVID-19 among health care professional’s working in South Wollo zone hospitals, Northeast Ethiopia. SAGE Open. Med.9, 20503121211025147 (2021).

Ashebir, W. et al. Knowledge, attitude, practice, and factors associated with prevention practice towards COVID-19 among healthcare providers in Amhara region, Northern Ethiopia: A multicenter cross-sectional study. PLOS Global Public. Health. 2 (4), e0000171 (2022).

Eyayu, M., Motbainor, A. & Gizachew, B. Practices and associated factors of infection prevention of nurses working in public and private hospitals toward COVID-19 in Bahir Dar City, Northwest Ethiopia: Institution-based cross-sectional study. SAGE Open. Med.10, 20503121221098238 (2022).

Tadesse, D. B., Gebrewahd, G. T. & Demoz, G. T. Knowledge, attitude, practice and psychological response toward COVID-19 among nurses during the COVID-19 outbreak in northern Ethiopia, New microbes and new infections. 2020;38:100787. (2020).

Tsegaye, D. et al. COVID–19 related knowledge and preventive practices early in the outbreak among health care workers in selected public health facilities of illu Aba Bor and Buno Bedelle zones, Southwest Ethiopia. BMC Infect. Dis.21 (1), 1–11 (2021).

Gebremedhin, T., Abebe, H., Wondimu, W. & Gizaw, A. T. COVID-19 prevention practices and associated factors among frontline community health workers in Jimma zone, Southwest Ethiopia. J. Multidisciplinary Healthc. 2239–2247 (2021).

Negera, A., Hailu, C. & Birhanu, A. Practice towards prevention and control measures of coronavirus disease and associated factors among healthcare workers in the health facilities of the horo guduru wollega zone, west Ethiopia, 2021. Global Health Epidemiol. Genomics. (2022).

Tsehay, A. et al. Factors associated with preventive practices of COVID-19 among health care workers in Dilla university hospital, Southern Ethiopia. Environ. Challenges. 5, 100368 (2021).

Adola, S. G. et al. Assessment of factors affecting practice towards COVID-19 among health care workers in health care facility of West Guji zone, South Ethiopia, 2020. Pan Afr. Med. J.;39(1). (2021).

Yesse, M. et al. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice toward COVID-19 and associated factors among health care workers in silte zone, Southern Ethiopia. PloS One. 16 (10), e0257058 (2021).

Tesfaye, Z. T., Yismaw, M. B., Negash, Z. & Ayele, A. G. COVID-19-related knowledge, attitude and practice among hospital and community pharmacists in addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Integr. Pharm. Res. Pract.105, 12 (2020).

Fetansa, G. et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of health professionals in Ethiopia toward COVID-19 prevention at early phase. SAGE Open. Med.9, 20503121211012220 (2021).

Jemal, B. et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of healthcare workers toward COVID-19 and its prevention in Ethiopia: A multicenter study. SAGE Open. Med.9, 20503121211034389 (2021).

Saqlain, M. et al. Knowledge, attitude, practice and perceived barriers among healthcare workers regarding COVID-19: a cross-sectional survey from Pakistan. J. Hosp. Infect.105 (3), 419–423 (2020).

Organization, W. H. Infection Prevention and Control during Health Care when Novel Coronavirus (nCoV) Infection Is Suspected: Interim Guidance, 25 January 20209240000917 (World Health Organization, 2020).

Nwagbara, U. I., Osuala, E. C., Chireshe, R. & Bolarinwa, O. A. Knowledge, Attitude, Perception and Preventive Practice Towards Novel Coronavirus 2019 in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Scoping Review Protocol. (2020).

Ogoina, D. et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice of standard precautions of infection control by hospital workers in two tertiary hospitals in Nigeria. J. Infect. Prev.16 (1), 16–22 (2015).

Kamabu, L. K. et al. Determinants of knowledge, attitudes, and practices of frontline health care givers during the first wave of Covid-19 in Africa: a Multi-centers online Cross-sectional. (2021).

Saadatjoo, S., Miri, M., Hassanipour, S., Ameri, H. & Arab-Zozani, M. A systematic review of the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of physicians, health workers, and the general population about coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). MedRxiv. 2020:2020.10. 04.20206094.

Honarbakhsh, M., Jahangiri, M. & Ghaem, H. Knowledge, perceptions and practices of healthcare workers regarding the use of respiratory protection equipment at Iran hospitals. J. Infect. Prev.19 (1), 29–36 (2018).

Saqlain, M. et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice among healthcare professionals regarding COVID-19: A cross-sectional survey from Pakistan. J. Hosp. Infect. (2020).

Girma, S., Alenko, A. & Agenagnew, L. Knowledge and precautionary behavioral practice toward COVID-19 among health professionals working in public university hospitals in Ethiopia: a web-based survey. Risk Manage. Healthc. Policy 1327–1334. (2020).

McEachan, R. et al. Meta-analysis of the reasoned action approach (RAA) to Understanding health behaviors. Ann. Behav. Med.50 (4), 592–612 (2016).

Nepal, R. et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice regarding COVID-19 among healthcare workers in Chitwan, Nepal. (2020).

Asdaq, S. M. B., Alshrari, A., Imran, M., Sreeharsha, N. & Sultana, R. Knowledge, attitude and practices of healthcare professionals of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia towards covid-19: a cross-sectional study. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.28 (9), 5275–5282 (2021).

Almohammed, O. A. et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practices associated with COVID-19 among healthcare workers in hospitals: a cross-sectional study in Saudi Arabia. Front. Public. Health. 9, 643053 (2021).

Saha, A. K., Mittra, C. R., Khatun, R. A. & Hasan, M. R. Nurses’ knowledge and practices regarding prevention and control of COVID-19 infection in a tertiary level hospital. Bangladesh J. Infect. Dis.7, S27 (2020).

Amanya, S. B. et al. Knowledge and compliance with covid-19 infection prevention and control measures among health workers in regional referral hospitals in Northern Uganda: A cross-sectional online survey. F1000Research10, 136 (2021).

Negera, A., Hailu, C., Birhanu, A. & Santangelo, O. E. Practice towards prevention and control measures of coronavirus disease and associated factors among healthcare workers in the health facilities of the horo guduru wollega zone, west Ethiopia, 2021. Global Health Epidemiol. Genomics. e5 (2022).

Shahrin, L. et al. In-person training on COVID-19 case management and infection prevention and control: evaluation of healthcare professionals in Bangladesh. PloS One. 17 (10), e0273809 (2022).

Islam, M. T. et al. Knowledge and practice on infection prevention among medical Doctors working at a COVID-19 unit of a tertiary care hospital in Bangladesh. Bangladesh J. Infect. Dis.8 (2), 57 (2021).

Matricardi, P. M., Dal Negro, R. W. & Nisini, R. The first, holistic immunological model of COVID-19: implications for prevention, diagnosis, and public health measures. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol.31 (5), 454–470 (2020).

Kamate, S. K. et al. Assessing knowledge, attitudes and practices of dental practitioners regarding the COVID-19 pandemic: A multinational study. Dent. Med. Probl.57 (1), 11–17 (2020).

Zhong, B-L. et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: a quick online cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Biol. Sci.16 (10), 1745 (2020).

Chawe, A. et al. Knowledge, attitude and practices of COVID-19 among medical laboratory professionals in Zambia. Afr. J. Lab. Med.10 (1), 1–7 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the team members for their valuable contribution from the conception to the final approval for submission to publication.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors’ ContributionsConceptualization: Gonete AT.Data curation: Gonete, AT, Workneh BS, Mekonen EG, Zegeye AF, Techane MA, Tsega SS, Wassie YA.Formal analysis: Gonete AT, Ali MS, Tekeba B, Wassie M, Techane MA, Tewodros Getaneh Alemu, Wassie YA.Investigation: Gonete AT, Tamir TT, Tsega SS, Ahmed MA, Kassie AT, Tekeba B.Methodology: Gonete AT, Tamir TT; Workneh BS, Alemu TG, Mekonen EG, Ali MS, Zegeye AF, Wassie M, Kassie AT, Techane MA, Ahmed MA, Tekeba BProject administration: Tekeba B and Techane MA, Tsega SS, Wassie YA.Software: Gonete AT, Tamir TT, Workneh BS, Alemu TG, Mekonen EG, Ali MS, Zegeye AF, Wassie M, Kassie AT, Ahmed MA, Tekeba B.Supervision: Gonete AT, Workneh BS, Ahmed MA, Ali MS, Tsega SS, Techane MA.Validation: Gonete AT, Ahmed MA, Wassie YAVisualization: Gonete AT, Tekeba B, Tamir TT, Alemu TG, Ahmed MA, Wassie YA.Original draft writing: Gonete AT.Writing – review & editing: Gonete AT, Tamir TT, Workneh BS, Alemu TG, Techane MA, Mekonen EG, Ali MS, Zegeye AF, Wassie M, Kassie AT, Tekeba B. Author declaration: All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gonete, A.T., Tamir, T.T., Techane, M.A. et al. Practice and associated factors of Covid-19 prevention among health professionals in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 15, 18462 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01919-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01919-x