Abstract

Future research directions aim to optimize the efficiency and sustainability of bismuth-based semiconductors for environmental remediation. In this study, potent Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 composites were synthesized via a facile in situ hydrothermal-assisted impregnation of Bi3+ onto WO3 nano-substrate. Comprehensive characterization using HR-TEM, SEM-EDX, PXRD, XPS, FTIR, PL, and DRS confirmed the structural, morphological, and optical properties of the synthesized materials. The optimized Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 heterojunction exhibited significantly enhanced photocatalytic activity under visible-light (λ > 350 nm) compared to pristine Bi2O3 and WO3, effectively degrading Indigo Carmine (IC) dye. The UV–Vis spectroscopy and chemical oxygen demand (COD) analyses validated the degradation efficiency. A detailed photocatalytic mechanism was proposed based on trapping experiments, band position calculations, and photoluminescence measurements. Furthermore, the fabricated nanocomposites demonstrated excellent stability and recyclability, highlighting their potential for environmental remediation. This study provides a promising strategy for designing efficient visible-light-driven photocatalysts for wastewater treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increasing discharge of toxic organic pollutants from industrial activities, particularly synthetic dyes, poses severe environmental and health concerns due to their high stability and resistance to conventional wastewater treatment methods1. This effluent contains organic and inorganic waste, which can directly affect chemical and biological variables. Notably, the textile sector plays a major role in contributing to these challenges. The textile industry emits many toxic pollutants, including solvents and hazardous textile dyes2. The effluent from colored textiles usually has elevated levels of dye compounds. Many of these dyes are harmful, cancerous, and capable of causing genetic mutations. Additionally, the release of dyes can lead to visible environmental changes. Indigo carmine (IC) is a well-established anionic indigoid dye that finds widespread application in various industries, such as textiles, food, and cosmetics3. Approximately 20,000 tons of IC dye are manufactured annually to produce blue jeans4. It is also utilized as a diagnostic tool for different medical applications. IC dye is hazardous, cancer-causing, and non-biodegradable, posing a significant risk to human health and causing detrimental impacts on the environment5. Additionally, it poses a multitude of risks to human health, including respiratory discomfort, gastrointestinal diseases, vision loss, and digestive and cognitive disorders6.

Semiconductor photocatalysis’s technology is an intriguing way to effectively eliminate a wide range of organic contaminants, particularly water-polluting dyes, when exposed to UV and/or solar radiation7,8. This process allows for completely degrading organic toxins at ambient temperature within a few hours, employing active photocatalysts9,10. Photocatalysts are semiconductors that can degrade a wide range of organic compounds, chemicals, and pharmaceutical products by generating reactive radicals and charge carriers upon exposure to light11. In recent years, novel photocatalysts have garnered significant attention for their potential in environmental remediation, particularly in addressing challenges such as water purification and air pollution12.

The construction of advanced heterojunctions has been widely recognized for its significant impact on the efficient separation and utilization of photo-generated charge carriers in photocatalytic processes13,14. In a heterojunction, two semiconductors with different band structures are coupled, allowing for the effective separation of photogenerated electrons and holes. This results in a decrease in charge recombination, which is a major hindrance to photocatalytic efficiency. The band alignment at the interface of the two semiconductors facilitates the transfer of electrons from the conduction band of one material to the conduction band of the other, while holes migrate to the valence band of the second material. This spatial separation of charge carriers enhances their lifetime and increases their participation in photocatalytic reactions, leading to improved overall photocatalytic performance15. Numerous studies have demonstrated that heterojunctions not only improve charge carrier dynamics but also enhance the absorption of visible light, further promoting the efficiency of photocatalytic processes16,17. Thus, the design of heterojunctions plays a crucial role in optimizing the photocatalytic activity of composite materials, making them highly effective in various environmental and energy-related applications.

Several metal oxide photocatalysts, including CeO2, ZrO2, ZnO, SnO2, TiO2, and Bi2O3, have demonstrated high effectiveness in degrading organic contaminants into benign water and CO2 byproducts18. Among these, tungsten trioxide (WO3) nanoparticles have emerged as a promising candidate due to their stability, non-toxicity, and wide applicability19. However, their limited absorption in the visible-light spectrum constrains their photocatalytic performance20. Consequently, substantial endeavors have been undertaken to create novel or altered semiconductor photocatalysts that are capable of harnessing visible light. Composite photocatalysts were implemented to optimize the longevity of the electron-hole charge carriers produced by light by minimizing their recombination rate21. Additionally, these heterostructure photocatalysts were designed to enhance their activity under visible light. The impregnation of WO3 nanoparticles with Bi3+ ions has garnered significant attention as a strategy to enhance their photocatalytic activity22. The incorporation of Bi3+ not only modifies the electronic structure of WO3 but also facilitates the formation of bismuth-based semiconductors, which exhibit improved visible-light absorption and charge separation efficiency23,24.

Numerous studies have been conducted on bismuth-based semiconductors to improve photocatalysis’s visible-light response, especially for creating various heterojunctions25,26. Bismuth tungstate (Bi2WO6), as an n-type semiconductor, has attracted significant attention in the scientific world due to its unique optical, electrical, and photocatalytic properties, making it a prominent photocatalyst among several bismuth-based counterparts27. It belongs to the Aurivillius-phase perovskite oxide category and is composed of fluorite-like [Bi2O2]2+ layers and [WO4]2− layers in a 1:1 stoichiometric ratio28. It has recently gained significant attention due to its potential as a visible-light-driven photocatalyst with an approximate band gap of 2.8 eV29. However, the rapid recombination of light-generated electron-hole pairs reduces energy conversion efficiency, which limits the use of BWO in photocatalysis30. The firmly developed heterojunction configuration can be implemented to restrict the recombination of the charge carriers and improve the quantum yield. Consequently, numerous researchers have coupled Bi2WO6 with various semiconductors, including TiO231, Ag3PO432, BiOBr25, V2O533, BiVO434, and ZnO35,36.

Bi2O3 is a p-type semiconductor with a band gap of ~ 2.8 eV. It has been demonstrated to act as a photocatalyst for water splitting and contaminants’ degradation when exposed to visible-light37. Nevertheless, the photocatalytic-efficiency of pure Bi2O3 is also limited due to the elevated chance of recombination between photogenerated holes and electrons38. However, the photocatalytic-activity is anticipated to be significantly enhanced by generating a p–n junction structure between the n-type Bi2WO6 and p-type Bi2O339,40. After reviewing the available literature, we noticed that there are no published reports on the in situ hydrothermal synthesis of Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 heterojunction via the impregnation of WO3 nanoparticles with Bi3+ ions to degrade IC dye efficiently. The photocatalytic-degradation parameters of the previous semiconductor heterojunctions toward IC dye are presented in Table 1. Thus, this study enables the development of a heterojunction system with synergistic photocatalytic properties by optimizing the interaction between WO3 and Bi3+ to harness the full potential of the resulting Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 composite to achieve efficient photocatalytic degradation of such hazardous industrial dye. The significance of these advances lies not only in their environmental applications but also in their ability to provide scalable, sustainable solutions for large-scale remediation efforts, ultimately advancing the field of photocatalysis for environmental protection.

This work investigated the synthesis of new composites consisting of x% weights of Bi3+ and WO3 NPs using an in-situ hydrothermal approach. This method has numerous advantages, including outstanding repeatability, narrow size distribution, high yield and elevated product purity. The beneficial features of the fabricated heterojunction were evaluated by examining the degradation of aqueous solutions of Indigo carmine (IC) dye under different light sources. The photocatalytic efficiency of the synthesized composite is compared to the individual components, Bi2O3 and WO3. The mechanism behind the improved photocatalytic efficacy was determined by calculating and analyzing the band structure. In addition, the active species involved in the degradation of IC dye on the optimized composite was examined and the catalyst’s cycling performance was evaluated. Ultimately, a plausible mechanism for the photocatalytic-degradation process was investigated.

Experimental section

Chemicals

The chemicals utilized in the study were employed without any additional purification. The precursors used were Sodium tungstate dihydrate [Na2WO4·2H2O], bismuth nitrate pentahydrate [Bi(NO3)3.5H2O], nitric acid (HNO3), acetic acid (CH3COOH, HAc), and urea (NH2CONH2). Polyethylene glycol with a molecular weight of 10,000 (PEG) was employed as a dispersant.

Synthesis of WO3 NPs

To synthesize nano WO3, approximately 0.03 mol (9.9 g) of sodium tungstate was dissolved in 150 ml of distilled water. Then, 3.75 g of PEG was added, stirring the mixture for 1 h. Concentrated acetic acid was slowly added drop by drop until the pH reached around 2–3. The resulting white suspension was agitated for a further 2 h at ambient temperature. The solution is transferred into a Teflon-lined cell and placed inside a stainless-steel autoclave in an oven set at 160 °C for 24 h. The product was washed with ethanol and water and then dried at 100 °C for one night. The desiccated sample was ultimately calcinated for 2 h in a muffle furnace at 500 °C, forming a greenish precipitation of WO3 NPs. The precipitate was thoroughly pulverized and subsequently utilized for further experimental work.

Synthesis of Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 heterojunctions

The Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 photocatalysts were synthesized using the in-situ hydrothermal technique. Initially, a molar ratio of 1.5:1 was established between Bi2O3 and WO3. Subsequently, 14.55 g of Bi(NO3)3.5H2O were dissolved in 100 ml of acetic acid (HAc). This solution was then slowly added drop by drop to 50 mL of deionized water containing 2.32 g of highly dispersed WO3 NPs. The resulting suspension was mixed with urea in a 1:5 molar ratio (50 ml) under vigorous magnetic stirring at room temperature. The mixture was agitated using a magnetic stirrer for 30 min at an ambient temperature. The suspension was then transferred to 250 ml Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclaves with a capacity of ~ 75% of their maximum volume. The autoclave was then heated to a specific temperature of 160 °C for 24 h. After the autoclaves cooled to room temperature, the precipitate was separated using centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 5 min. The sample was subjected to three washing cycles with deionized water and ethanol to eliminate any potentially interfering ionic species. The resulting mixture was subjected to drying at a temperature of 100 °C for 24 h. The dried sample was subjected to calcination for 2 h in a muffle at 500 °C, forming bright yellow precipitates to harvest the Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 composite, labelled as a BW1 sample. The inclusion of the (Bi2WO6) phase in the composite is attributed to the effectiveness of hydrothermal treatment (HT) in the presence of urea (pH ≈ 10), as indicated by the chemical reaction below58:

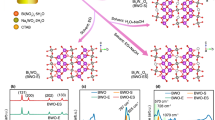

For comparison, composites with molar ratios of Bi2O3:WO3 at 1:1 and 0.5:1 were synthesized and labeled as BW2 and BW3 samples, respectively. Besides, Bi2O3 powders were synthesized via a hydrothermal technique using identical preparation conditions indicated earlier, excluding adding WO3 NPs. The synthesis-steps of Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 heterostructures were summarized in Fig. 1.

Photocatalytic performance experiments

The photocatalytic performance of the fabricated nanomaterials was evaluated in a photoreactor equipped with UVA (6w, 365 nm, ~ 1100 mW/cm2), UVC (6w, 254 nm, ~ 1050 mW/cm2), and LED (15w, λ ≥ 380 nm, ~ 1350 mW/cm2) light sources at room temperature (~ 30 °C). The degradation of the Indigo carmine (IC) dye (C16H8N2Na2O8S2, 466.36 g/mol) was monitored during the experiment. For every degradation experiment, a 100 ml aqueous solution containing IC was carefully poured into the beaker, maintaining a consistent initial concentration of 50 mg/l (50 ppm). Then, a specific amount of the photocatalyst (50 mg) was added to the solution while continuously stirring it with a magnetic stirrer for 30 min. This step was carried out in a dark environment to ensure that the adsorption-desorption equilibrium was achieved before proceeding with the photocatalytic-degradation. The light was then activated to initiate the degradation process. At regular time intervals of 10 min, a 2 mL portion of the suspension was carefully extracted and subjected to centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 3 min. The solution was then analyzed using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer to determine its absorbance maximal at 610 nm. A calibration curve was employed to ascertain the IC concentration based on the peak absorbance. An extensive examination of multiple factors, such as pH, catalyst dosage, contact duration, initial dye concentration, and trapping agents, was successfully conducted. The degradation efficiency of the synthesized catalysts has been evaluated using Eq. (1):

where, A○ and At are the absorbance readings of IC before and after exposure to light, respectively.

According to the Hinshelwood–Langmuir approach, the photodegradation of organic toxins usually follows the pseudo-first-order kinetics, so the photo-decolorization rate of IC dye was studied by Eq. (2):

where (C0) is the initial concentration and (Ct) is the concentration at any time, t. The rate constants (k) were estimated from the slopes of the straight-line segment of the plots of ln(C0/Ct) versus t for each reaction.

The COD of the dye solution was measured before and after the photolysis reactions at regular irradiation intervals to determine if only discoloration or complete dye mineralization takes place during the photodegradation process using the dichromate-oxidation method59. The mineralization proficiency was determined by Eq. (3):

CODi was the value measured before exposure to light, while CODf was the COD-value measured after exposure to light at regular time intervals. The measurements were done three times, and the mean values were noted.

Detection of active species

Quenching tests were conducted to provide insight into the active species and potential photocatalytic pathways. The experiment followed a similar procedure to the photocatalytic test, including adding scavengers to the reaction solutions before introducing the photocatalyst. The photodegradation systems utilized 0.5 mmol of p-benzoquinone (p-BQ), ammonium oxalate (AO), potassium dichromate (K2Cr2O7), and isopropyl alcohol (IPA) as scavengers. These scavengers were employed to effectively suppress the activity of superoxide radicals (·O2−), photo-holes (h+), photoelectrons (e−), and hydroxyl radicals (·OH), respectively.

Results and discussion

Morphological and structural features of synthesized materials

To identify the role of synthesized nanomaterials (WO3, Bi2O3 and BW1) and measure their efficiencies in photocatalytic degradation for Indigo carmine (IC) dye, their phase composition, degree of crystallinity, functional group, morphology, purity, and crystal size were examined using XRD, FTIR, SEM/EDX and HRTEM/SAED. The composite BW1 was specifically selected for a comprehensive characterization while disregarding the other composites (BW2 and BW3) because the BW1 composite exhibited the highest catalytic activity in degrading the target dye (IC), which will be explained in more detail later.

Phase identification

Powder X-ray diffraction was utilized to ascertain the phase composition of the solid powders and to confirm the successful synthesis of the synthesized materials60,61. The XRD analysis (Fig. 2) shows that all synthesized nanomaterials have high purity. The XRD-diffractogram of WO3 NPs displays several distinguish peaks having different crystallographic-planes with specific reflection-peaks (hkl) at 2Ɵ= 23.11° (002), 23.57° (, 24.35° (200), 26.59° (120), 28.96° (121), 33.25° (022), 34.15° (202), 41.64° (221), 49.89° (140) and 55.89° (420), matching with Hatel and Baitoul62. These peaks refer to the formation of pure monoclinic WO3 NPs, according to PDF# 01-072-0677. The peaks observed in XRD-diffractogram of Bi2O3 NPs at 2Ɵ= 25.75° (002), 26.91° (111), 27.39° (120), 28.01° (012), 33.26° (200), 35.04° (210), 37.62° (112) and 46.34° (221) are related to monoclinic α-Bi2O3 NPs according to PDF# 01-071-2274, as identified by Oudghiri-Hassani et al.63. For the Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 heterostructure, four prominent peaks are detected at 2Ɵ= 28.37, 32.85, 47.11, and 55.93°. At each peak, there are two overlapped phases are identified, which are cubic Bi2O3 (PDF# 01-076-2478 with reflection-peaks 111, 200, 220 and 311, respectively) and orthorhombic Bi2WO6 (PDF# 01-073-1126 with reflection-peaks 131, 200, 202 and 133, respectively), in line with Singh et al.64. It is important to notice that the overlap of the diffraction peaks of Bi2O3 and Bi2WO6 in the BW1 composite indicates the effective development of Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 heterostructure via this synthesis route65. Moreover, the absence of any additional phases is confirmed, indicating the samples’ great purity.

From XRD-analysis, the degree of crystallinity was measured using Match! 3 version 3.15 software. All the samples exhibit a satisfactory level of crystallinity. It was found that the degree of crystallinity of WO3 NPs > Bi2O3 NPs > Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 heterostructure; their values are 81.22%, 77.12%, and 76.95%, respectively. Also, the average crystal-size was calculated using Debye–Scherrer’s equation (D = Kλ/βcosƟ), where D: crystal-size, K: shape-factor (equal 0.92), λ: wavelength of X-ray (1.5406 A°), β: full-width at half-maximum, FWHM), and θ: scattering-angle. It was found that the crystal sizes of WO3 NPs ranged from 9.58 to 42.88 nm with an average size of 25.67 nm, Bi2O3 NPs ranged from 7.78 to 50.71 nm with an average size of 36.71 nm, and Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 composite ranged from 6.88 to 31.22 nm with an average size of 18.10 nm. The smaller particle size of the Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 composite with respect to WO3 and Bi2O3 may be attributed to the acting of the Bi2WO6 nanoparticles as a nucleation site for Bi2O366. This results in increasing dispersion and thus reducing the particle size67. Also, these results match the degree of crystallinity; the low degree of crystallinity refers to the low particle size. Kominami et al.68 and Sudrajat and Sujaridworakun69 reported that the degree of crystallinity of small particles is lower than that of large particles. Moreover, the high surface area of Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 composite with respect to WO3 and Bi2O3, as will be illustrated below (“Textural parameters studies”), is strong evidence of the smaller particle size of the nanocomposite.

Functional group identification

The FTIR-spectra of WO3, Bi2O3 and Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 are represented in Fig. 3 to confirm their structure by identifying various bonds’ existence. The spectrum of each sample displays several transmittance-bands at different wavenumbers. The WO3 NPs’ spectrum demonstrates the presence of three bands affiliated to δ W-O-W stretching, υ W-Ointer-W bridge stretching and υ W =O symmetrical stretching, which are centered at 624, 803 and 1042 cm− 1, aligning well with results from earlier comparable studies19,70. For Bi2O3 NPs, three bands are observed associated with vibrations of the Bi–O bond at 430 and 496 cm− 1 and Bi–O–Bi stretching at 843 cm− 1, aligning with Li et al.71. The band detected at 1374 cm− 1 may be correlated to N–O bending vibrations of NO3− resulting from the Bi2(NO3)3.5H2O precursor used in the preparation procedure, as described by Priscilla et al.72. Regarding Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 heterostructure, absorption bands in the range 500–1000 cm− 1 are assigned to the metal-oxygen stretching bond. The Bi-O stretching, W-O stretching and W–O–W bridge stretching bands are found at 585, 705 and 815 cm− 1, respectively, as identified by Salari73, Zhou et al.74, Song et al.75 and Dong et al.76. Furthermore, the bands observed within this region correspond to the orthorhombic phase of Bi2WO677. These results affirmed the formation of pure WO3 NPs, Bi2O3 NPs and Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 heterostructure.

Surface morphological analysis

The morphology, purity, and particle size distribution of synthesized materials were investigated using SEM/EDS-mapping/EDX (Fig. 4) and HR-TEM/SAED (Fig. 5). The SEM-micrographs reveal that the WO3 NPs, Bi2O3 NPs and Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 heterostructure have spheroid-like structure (matched with Sayed et al.19), worm-like structure (matched with Moghadam and Farzaneh78) and nano-flakes developed hierarchical flower-like structure (matched with Dong et al.76), respectively. The spheroid particle characteristics of WO3 disappeared and were transformed into a newly generated hierarchical structure in the composite. Furthermore, the presence of substantial clusters of Bi2WO6 and the accumulation of nanosized Bi2O3 particles on the outer surface provide unambiguous evidence of the creation of a Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 composite (Fig. 4c). The elemental analysis using EDS-mapping/EDX shows a uniform distribution of the elements as well as the presence of W and O only in WO3 NPs, Bi and O only in Bi2O3 NPs and W, Bi and O in Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 heterostructure. The absence of impurities in the samples confirms the high purity level of synthesized samples. The TEM images (Fig. 5a,c) revealed the presence of highly agglomerated nanosized particles, which corresponded to the particle morphologies observed in the SEM images (Fig. 4). The significant agglomeration can be ascribed to the highly minute particle size dispersion in the examined samples79. On the other hand, HR-TEM/SAED images/patterns (Fig. 5d–f) provide information on atoms on the NPs’ crystal lattice by measuring the interplanar spacing (d-spacing, nm) and identifying the lattice fringes. The d-spacing of WO3 NPs is 0.27 nm, corresponding to (200) crystallographic-plane of monoclinic WO3 NPs (PDF# 01-072-0677). The d-spacing of Bi2O3 NPs is 0.31 nm, relating to (120) crystallographic-plane of monoclinic α-Bi2O3 NPs (PDF# 01-071-2274). In BW1 composite (Fig. 5f), there are two distinct patterns of lattice fringes with interplanar d-spacings of 0.31 nm and 0.35 nm, correlating to (131) crystallographic-plane of orthorhombic Bi2WO6 NPs (PDF# 01-073-1126) and (111) crystallographic-plane of cubic Bi2O3 NPs (PDF# 01-076-2478), respectively, confirming the successful formation of heterostructure composite. The estimated d-spacing values and their related lattice planes from this pattern are accurately fitted with the XRD data. Furthermore, the SAED patterns revealed that the spot analysis areas of all the manufactured materials exhibited a distinct lack of ambiguity, indicating a significant level of crystallinity, particularly in polycrystalline forms. These findings align with those obtained from the PXRD study depicted in Fig. 2.

XPS analysis

XPS-analysis was performed quantitatively on the fabricated BW1 heterostructure. The full survey and high-resolution spectra for the Bi4f, W4f, and O1s species (Fig. 6) indicated the presence of only O, Bi, and W elements in the sample. The XPS-spectrum of the W4f zone displayed peaks at binding energies of 36.1 eV (W 4f7/2) and 38.0 eV (W 4f5/2), characteristic of the W6+ oxidation state80,81. However, low-intensity peaks at 40.0 eV may have resulted from the existence of W5+ and oxygen vacancies in the Bi2WO6 matrix82. The deconvoluted Bi4f spectrum exhibited peaks at binding energies of 165.8 eV (Bi 4f5/2) and 160.5 eV (Bi 4f7/2), confirming the presence of the Bi3+ state83,84,85. Although these binding energies are indicative of Bi3+ and W6+ species, they do not precisely match those observed in pure Bi2O3 or Bi2WO6, suggesting the formation of a unique chemical environment in the BW1 heterostructure. This observation also implies forming an interfacial structure, resulting in a modification of the constituent elements’ local environments and electron densities38. The O 1s XPS-spectrum could be deconvoluted into three peaks centered at 530.5, 532, and 534.5 eV, which were attributed to Bi–O and W–O bonds in Bi2WO6 and Bi–O bonds in Bi2O3, respectively86,87,88,89. Besides, oxygen vacancies within the composite lattice are observable through an asymmetric profile of the O1s profile90. In contrast, the XPS-analysis of sample BW1 revealed that the surface contains 23.9 atom% Bi3+ and 9.6 atom% W6+. The proportion of bismuth to tungsten atoms is approximately 2.5, exceeding the stoichiometric ratio found in Bi2WO6. The finding shows that both Bi2O3 and Bi2WO6 species are present in the BW1 composite, which agrees with the findings obtained from XRD, HR-TEM, and SEM analyses.

Textural parameters studies

The texture parameters were analyzed via Brunauer–Emmett–Teller model (BET) and Barrett–Joyner–Halenda model (BJH). Figure 7a,b displays N2-adsoprtion/desorption isotherms and BJH-pore size distribution curves for the prepared metal oxides. According to IUPAC classification, Fig. 7a confirms that WO3 and Bi2O3 obey Type III isotherm while Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 obey Type III/H3 hysteresis-loop reflecting the meso-porous nature of the prepared composite. The hysteresis is attributed to the capillary condensation phenomena91,92 inside the mesoporous system of Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 of 105 nm maximum and pore diameter, as clarified in Fig. 7b. Moreover, Table 2 affirms that Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 NPs possess the highest textural parameters as compared with single oxides as the BET-specific surface area (S.S.A), monolayer capacity (Vm), and total pore volume (Vt) are 6.57 m2/g, 1.51 cm3/g, and 0.127 cm3/g, respectively. Thus, these outcomes indicate that the prepared Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 NPs will have a distinct photo-catalytic performance compared to WO3 and Bi2O3 NPs and will hence act as effective active centers for the degradation of the target dye93.

Optical properties

UV–Vis diffuse reflectance spectral studies (UV-DRS)

For evaluating the photocatalytic-performance of the synthesized photocatalysts, it is crucial to consider the specific range of wavelengths of light that they can absorb94. Hence, the optical characteristics of the synthesized nanocomposite (BW1) were investigated using UV-DRS analysis and compared to the pristine WO3 and α-Bi2O3 nanoparticles, as depicted in Fig. 8. The DRS spectra of pure WO3, α-Bi2O3, and BW1 composite exhibited an optical absorption edge at wavelengths of 452 nm, 456 nm, and 439 nm, respectively, as displayed in Fig. 8a. This demonstrates their abilities to absorb visible light. Nevertheless, the BW1 composite exhibits absorption shoulders at approximately 490 nm, suggesting that this catalyst has a greater capacity for absorbing light across a wide range of visible regions. The enhanced visible-light absorption of BW1 composite material can be attributed to the surface plasmon band heterojunction by the well-distributed Bi2O3 nanoparticles95. Besides, upon the amalgamation of the two semiconductors, Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 heterojunction (BW1) exhibits heightened absorption within the visible-light spectrum, surpassing that of pure α-Bi2O3 or WO3 components. The direct bandgap energy (Eg) of the synthesized semiconductors was determined by fitting the absorption data to the direct transition equation (Tauc’s equation)96:

where α is the absorption coefficient, hυ is the photon energy, Eg is the direct bandgap of the material and A is constant. The bandgap energies of synthesized materials have been measured by plotting (αhυ)2 as a function of photon energy (hυ) and extrapolating the linear portion of the curve to absorption equal to zero97. The plots of (αhυ)2 versus (hυ) are shown in Fig. 8b and the corresponding bandgap energies depending upon these plots were determined to be 2.8 eV, 2.78 eV, and 2.93 eV for WO3, α-Bi2O3, and BW1 composite, respectively. The increase in the bandgaps upon the formation of the Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 nanocomposites, as observed in our study, can be attributed to the interactions between the Bi2O3 and Bi2WO6 components. Specifically, the formation of the heterojunction can lead to a shift in the electronic structure of both semiconductors40,98. The interface between the two materials can result in band bending, which may affect the electronic states and the absorption of light. Furthermore, the increase in bandgap could also be a result of the quantum confinement effects in the nanocomposite, as the size of the particles decreases during synthesis99. Clearly, the integration of Bi2O3 nanoparticles into Bi2WO6 improves its ability to absorb visible light. This can be attributed to the mutual photosensitization of Bi2O3 and Bi2WO6 surfaces100.

Photoluminescence (PL) measurements

Photoluminescence (PL) experiments were conducted on all the manufactured solid samples to examine the photogenerated electron-hole pairs’ lifespan. The PL spectra are directly associated with the transfer dynamics of the photoexcited electrons and generated holes. The samples exhibited green emission bands spanning a wavelength range of 450 to 550 nm (Fig. 9). The recombination of electron-hole pairs is responsible for the intense emission bands observed in bare WO3 and Bi2O3 nanoparticles101,102. In contrast, the PL emission intensity of the composite Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 (BW1) is considerably lower compared to individual precursors, suggesting a reduction in the photogenerated charges’ recombination103. This reduction causes a significant increase in the lifetime of the reactive radicals that are produced104. Thus, the electron and hole pairs generated by light absorption are less likely to be recombined because the charge carriers are spatially separated across the heterojunction, which leads to a decrease in PL intensity despite the relative increase in bandgap15,105.

Photocatalytic performance of synthesized nanomaterials

Effect of catalyst type

The fabricated materials were analyzed for their photocatalytic-characteristics by observing the degradation of Indigo carmine (IC) dye under UV-A irradiation, as depicted in Fig. 10a,b. The matching UV-visible absorption spectra can be seen in Supplementary Information (Fig. S1). The photoactivities of the samples in degrading IC dye diminish in the following order: BW1 > Bi2O3 > BW2 > BW3 > WO3. To conduct an additional screening test, photolysis was carried out by activating the light source without the presence of any photocatalysts. The elimination efficiency after 2 h was approximately 8%. Regarding the effect of pollutant adsorption on photocatalysis, we would like to point out that the adsorption capacity of the applied catalysts is relatively small, with a maximum adsorption percentage of no more than 7%. As a result, the impact of pollutant adsorption on the overall photocatalytic degradation process is minimal. However, the degradation percentage was evaluated after irradiation, i.e., during the photoreaction step, following the dark adsorption phase. The pure WO3 NPs exhibited the lowest degrading efficiency, ~ 21%, after 2 h. However, efficiency is significantly enhanced by the incorporation of Bi2O3 and the creation of composite heterostructures. The BW1 composite demonstrated the highest photodegradation performance level in the IC dye, achieving an efficiency of 99.7%. Generally, the impregnation of Bi2O3 to WO3 in the synthesized composites, 1:1 in BW2, 0.5:1 in BW3, and 1.5:1 in BW1 improved the photocatalytic activity of the resulting composite in degrading IC dye. Including an excessive amount of Bi2O3 in the composition of the (BW1; Bi2O3/Bi2WO6) catalyst reduces the recombination rate of electron-hole pairs. Consequently, this increases the involvement of many electron-hole pairs in the photocatalytic-reaction, resulting in enhanced catalytic activity. This observation aligns with the findings documented in various investigations in the literature10,106. As a result, the BW1 composite was chosen for additional studies to optimize photocatalytic-activity features.

Effect of catalyst dose

The impact of various doses of BW1 composite (ranging from 0.5 to 1.5 g L− 1) on its efficacy in degrading IC dye is illustrated in Fig. 11, along with their respective UV-visible absorption spectra in Fig. S2. The current degradation process occurs under UV-A light irradiation at varied time intervals for an initial concentration of 50 ppm of IC dye. In general, the degradation percentage of IC dye increased as the amount of photocatalyst increased at different intervals of reaction, as shown in Fig. 11a. The degradation percentage achieved a maximum of 98.9% after 120 min when an increased quantity of catalyst, specifically 1.5 g/L, was used. In addition, a pseudo-first-order model was employed to establish a relationship between the data on photo-degradation reactions of IC dye and the various catalyst doses of BW1 composite. The rate constant k (min− 1) was determined by calculating the slope of the natural logarithm of the initial concentration divided by the concentration at a given time (i.e., ln C0/Ct), plotted against time (t) as presented in Fig. 11b. The degradation of IC dye over BW1 composite using different doses was well described by the pseudo-first-order model, with an R2 value of approximately 0.97. The maximum degradation rate constant (kapp) for IC dye was determined to be 0.021 min− 1, using a concentration of 1.5 g/L of BW1 composite (Table 3).

Effect of light source

The impact of different light sources on the photocatalytic–degradation of IC dye using the BW1 catalyst was demonstrated in Fig. 12a, and its related UV-visible absorption spectra are shown in Fig. S3. Four distinct light sources were utilized: UV-A (λ = 365 nm), UV-B (λ = 256 nm), LED-lamp, and Hg-lamp. The degradation efficiency rate is ordered as: UV-A > Hg-lamp > UV-B ≈ LED in degrading IC dye within 2 h of irradiation. Generally, the photocatalytic degradation of IC dye is greater when exposed to UV irradiation compared to visible irradiation at various time intervals. This phenomenon can be explained by the fact that UV-A light possesses greater energy than visible-light, allowing UV light to readily permeate the catalyst reaction slurry, which leads to greater activation of the catalyst, creating a higher number of electrons and holes107. Despite the high energy of UV-B radiation, the degradation efficiency is relatively low. This observation demonstrates that increasing the photon flux is insufficient if it does not align with the effective band gap of the photocatalyst108. However, as depicted in Fig. 12b, the pseudo-first-order model accurately represented the degradation of the IC dye by BW1 under the applied light sources, indicating that the degradation process over the BW1 catalyst under both UV and visible irradiation occurs through an identical chemical pathway. The degradation rate constants were determined as follows: 0.011 min− 1 for UV-A, 0.007 min− 1 for Hg-lamp, 0.002 min− 1 for UV-B, and 0.002 min− 1 for LED-lamp (Table 3).

Effect of initial pH

The impact of pH on the photocatalytic-degradation of IC dye using the BW1 composite was illustrated in Fig. 13 and its related UV-visible absorption spectra in Fig. 14. The data shows that when the pH of the solution increased, the percentage of photodegradation of IC dye over BW1 also increased. The highest degradation level was achieved at a pH of 12 after 2 h. Given that IC is an anionic dye, it was anticipated that the degradation would decrease as the pH of the dye solution increased, and the dye removal would be generally lower in alkaline pH solutions. However, the XPS results can provide insight into the potential cause of the existence of oxygen vacancies within the lattice of the BW1 composite. In an alkaline dye solution, the presence of hydroxide ions can induce ionization of these groups, forming negatively charged oxygen groups109. Therefore, we can hypothesize that the photoinduced positive hole (h+) on the surface of BW1 is likely to react with these ionized negative oxygen groups. This also results in a restriction of the diffusion of holes towards the interface between the composite and the reaction solution, impeding the recombination of electrons (e−) and holes (h+)110. Furthermore, the higher concentration of OH− ions, as opposed to H+ ions, in the reaction medium can enhance the creation of more reactive oxygen species (ROS) that facilitate the photo-degradation process111. Consequently, the rate of indigo degradation over BW1 showed a consistent increase as the pH increased. This behavior is similar to observations documented in prior studies10,112. However, the natural pH value (7.5–8) was selected for all experiments and further studies due to its ease of application in treating aqueous media without prior treatments.

Trapping experiments and photocatalytic mechanism

Experiments to confine active species for the degradation process were carried out to clarify the photocatalytic mechanism of the most potent BW1 catalyst. The scavengers like Benzoquinone (BQ), ammonium oxalate (AO), potassium dichromate (K2Cr2O7), and isopropyl alcohol (IPA) were employed to effectively suppress the activity of superoxide radicals (·O2−), photo-holes (h+), photoelectrons (e−), and hydroxyl radicals (·OH), respectively113. The results are portrayed in Fig. 15 and Fig. S4. The results showed that the photodegradation percentage of IC dye on BW1 decreased from 96.7 to 88.5%, 3.3%, 24.9%, and 27.7% with the inclusion of IPA, BQ, K2Cr2O7, and AO, respectively. Thus, it can be deduced that the superoxide radicals play a key role in the degradation process, while the photo-induced electron-hole pairs have a subordinate impact and hydroxyl radicals have a minimal effect. This also suggests that photogenerated holes are not solely the cause of the photodegradation of IC dye.

Generally, the type-II heterojunction and Z-scheme structure are the two factors that determine how charges are separated between Bi2O3 and Bi2WO6103. Upon exposure to visible-light, Bi2O3 with a narrow bandgap becomes activated, generating photoelectrons and holes. The electrons in the conduction-band of the p-type Bi2O3 are transferred to the conduction band of the n-type Bi2WO6 since the Fermi energy level (Ef) is closer to the CB of Bi2WO6, while the holes stay fixed in the valence-band of Bi2O338. This is advantageous for minimizing their recombination. The electrons produced by light were captured by O2, forming O2−• and H2O2, then generating hydroxyl radicals114. Besides, the photogenerated holes in Bi2O3 strongly oxidize unsaturated organic contaminants, causing them to be mineralized into CO2 and H2O115. The role of the photogenerated holes in the degradation of organic compounds over the Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 catalyst has been well established. Also, the migration rates of the photogenerated electrons and holes are accelerated by the internal electric field within the Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 heterojunctions, significantly enhancing the photocatalytic activity. After carefully analyzing the experimental results, we have formulated the most likely type-II heterojunction degradation mechanism of IC dye under visible-light irradiation, as represented in Fig. 16. This proposed mechanism is very consistent with many previous studies documented in literature98,103,116.

Mineralization of dye

The chemical oxygen demand (COD) is a way to indirectly determine the total organic compounds present in wastewater by measuring the oxygen required for oxidizing organic matter using a chemical oxidant like potassium dichromate117. The ultimate objective of the photocatalytic-degradation of organic of the organic dye molecule to CO2 and H2O118. Through examination of the spectral curve of IC dye through photo-degradation experiments, a gradual decline in the dye’s absorption over time was observed across the entire absorption spectrum, without any shifting or new peaks emerging or a significant increase in absorption at any specific wavelength. The reduction in absorbance of the IC dye solution over time is primarily caused by photodegradation and dye conversion into CO2 and H2O, as documented in various previous research studies94,119,120,121. Nonetheless, assessing mineralization solely through spectrophotometric methods is not feasible. Hence, COD was utilized in current research. Table 4 provides the (CODi) and (CODf) values for IC dye during photocatalytic degradation at various time intervals. The mineralization efficiency of Indigo carmine (IC) dye reached a maximum of 88.9% after 180 min of treatment with the BW1 catalyst. However, when the initial COD was adjusted to account for dye adsorbed, the effective mineralization efficiency was slightly lower at 88.1%. Thus, the data of COD and UV-Vis are consistent with the confirmation that it is not merely discoloration but that the dye’s mineralization occurs into smaller fragments during photocatalytic-reaction117.

Reusability of catalyst

This study examined the photocatalytic-stability of the optimized BW1-catalyst in the degradation of IC dye after four consecutive cycles (Fig. 17). The tests were conducted with an initial dye concentration of 50 ppm, a catalyst dosage of 1.5 g/L, and an irradiation period of 120 min at room temperature under UV-A irradiation. As shown in Fig. 18, the BW1 photocatalytic reactivity indicates that approximately 90% of the dye is mineralized throughout the four cycles, indicating significant reusability. The repetitive FTIR-spectra (Fig. 18A) and PXRD-pattern (Fig. 18B) of the recycled nanocomposite were analyzed. The repetitive spectra of the recycled composite (BW1) demonstrate the presence of the primary characteristic peaks for the synthesized composite across four successive cycles, showing its structural stability.

Comparison with other catalysts

Importantly, based on our literature review, no prior studies have reported the use of Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 nanocomposites specifically for the degradation of Indigo Carmine dye under visible light irradiation. This underlines the novelty of our work and demonstrates the potential of our composite as an efficient visible-light-driven photocatalyst for this organic pollutant. The Bi2O2/Bi2WO6 composite exhibited near-complete degradation (~ 100%) of Indigo Carmine (IC) dye after 120 min of visible light exposure. This high efficiency ranks among the best in our dataset (Table S1) and is on par with other catalysts used for similar dye degradation.

Conclusions

This study explores the role of Bi3+ impregnation in enhancing the visible-light response of WO3 nanoparticles and discusses its implications for the design of efficient inorganic photocatalysts. Highly efficient Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 nanocomposites were synthesized through a facile in-situ hydrothermal method, employing WO3 as a substrate and followed by annealing. This approach created a tightly bonded interface between the two semiconductors, facilitating efficient charge carrier transfer and separation. The resulting Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 composite demonstrated significantly enhanced photocatalytic-activity for hazardous indigo carmine (IC) dye degradation under visible-light irradiation, with the optimal performance observed for the 1.5 wt% Bi2O3:Bi2WO6 catalyst. The superior photocatalytic activity resulted from the synergistic effect between Bi2O3 and Bi2WO6, which broadened the visible-light absorption range and separated charge efficiently at the heterojunction interface. Radical and hole-trapping experiments revealed that the photoinduced-electrons and superoxide-radicals were the main reactive species that caused the degradation process. This study presents a promising strategy for developing novel heterojunction photocatalysts to remove hazardous organic pollutants efficiently.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kishor, R. et al. Ecotoxicological and health concerns of persistent coloring pollutants of textile industry wastewater and treatment approaches for environmental safety. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9, 105012 (2021).

Tavangar, T., Karimi, M., Rezakazemi, M., Reddy, K. R. & Aminabhavi, T. M. Textile waste, dyes/inorganic salts separation of cerium oxide-loaded loose nanofiltration polyethersulfone membranes. Chem. Eng. J. 385, 123787 (2020).

Sukhadeve, G., Shaileshkumar, Y., Janbandhu, R., & Kumar, R. S. Gedam Ag-doped TiO2 nanoparticles as an effective photocatalyst for degradation of Indigo Carmine dye under visible light. Chemistryselect. 6 12873–12883 (2021).

Rendón-Castrillón, L. et al. Treatment of water from the textile industry contaminated with Indigo dye: A hybrid approach combining bioremediation and nanofiltration for sustainable reuse. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 8, 100498 (2023).

Chaudhary, R. G. et al. Preparation of mesoporous ThO2 nanoparticles: influence of calcination on morphology and visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of Indigo Carmine and methylene blue. Environ. Res. 222, 115363 (2023).

Oliveira, L. V. et al. Free-standing cellulose film containing manganese dioxide nanoparticles and its use in discoloration of Indigo Carmine dye. Carbohydr. Polym. 230, 115621 (2020).

Zhang, G. et al. Fabrication of Bi2MoO6/ZnO hierarchical heterostructures with enhanced visible-light photocatalytic activity. Appl. Catal. B. 250, 313–324 (2019).

Ferdosi, E., Bahiraei, H. & Ghanbari, D. Investigation the photocatalytic activity of CoFe2O4/ZnO and CoFe2O4/ZnO/Ag nanocomposites for purification of dye pollutants, separation and purification technology, 211 35–39 (2019).

Kumar, S., Sharma, S., Kaushik, R. & Purohit, L. Chalcogen-doped zinc oxide nanoparticles for photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B under the irradiation of ultraviolet light. Mater. Today Chem. 20, 100464 (2021).

Abdeldayem, H. M. & Sayed, M. A. Synthesis and characterization of Ag/Ce1-XBiXZnO composites hosted α-β/Bi2O3 as highly efficient catalysts for degradation of cationic and anionic dyes. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A. 427, 113773 (2022).

Kannan, K., Radhika, D., Sadasivuni, K. K., Reddy, K. R. & Raghu, A. V. Nanostructured metal oxides and its hybrids for photocatalytic and biomedical applications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 281, 102178 (2020).

Zhang, J., Yu, G., Yang, C. & Li, S. Recent progress on S-scheme heterojunction strategy enabling polymer carbon nitrides C3N4 and C3N5 enhanced photocatalysis in energy conversion and environmental remediation. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 45, 101040 (2024).

Marschall, R. Semiconductor composites: strategies for enhancing charge carrier separation to improve photocatalytic activity. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 2421–2440 (2014).

Okab, A. A. et al. A comprehensive review highlights the photocatalytic heterojunctions and their superiority in the photo-destruction of organic pollutants in industrial wastewater. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 158, 111503 (2023).

Zhang, P., Wang, T., Chang, X. & Gong, J. Effective charge carrier utilization in photocatalytic conversions. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 911–921 (2016).

Li, S. et al. Interfacial Mo–S bond modulated S-scheme Mn0.5Cd0.5S/Bi2MoO6 heterojunction for boosted photocatalytic removal of emerging organic contaminants. Chin. J. Catal. 68, 259–271 (2025).

Shen, C. et al. Surface plasmon effect combined with S-scheme charge migration in flower-like Ag/Ag6Si2O7/Bi12O17Cl2 enables efficient photocatalytic antibiotic degradation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 679, 161303 (2025).

Sayed, M. A., Ahmed, M., El-Shahat, M. & El-Sewify, I. M. Mesoporous polyaniline/SnO2 nanospheres for enhanced photocatalytic degradation of bio-staining fluorescent dye from an aqueous environment. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 139, 109326 (2022).

Sayed, M. A. et al. Towards a green climate: production of slag–red brick waste-based geopolymer mingled with WO3 nanoparticles with bio-mechanical achievements. Constr. Build. Mater. 413, 134909 (2024).

Govindaraj, T., Mahendran, C., Marnadu, R., Shkir, M. & Manikandan, V. The remarkably enhanced visible-light-photocatalytic activity of hydrothermally synthesized WO3 nanorods: an effect of Gd doping. Ceram. Int. 47, 4267–4278 (2021).

Adhikari, S. P. et al. Visible-light-driven Bi2O3/WO3 composites with enhanced photocatalytic activity. RSC Adv. 5, 91094–91102 (2015).

Karuppannan, R. Design and Development of bismuth-based Ternary Oxides and their Hybrid Composites for solar-driven Photocatalytic Degradation of Pharmaceutical Pollutants (Université Laval, 2021).

Gong, Z., Zhang, W., Pan, S. & Pan, J. Ag+/Bi3+ doping induced band structure and optoelectronic properties changes in CsPbBr3 crystals. J. Cryst. Growth. 586, 126604 (2022).

Lee, J. Y., Lee, S., Ryu, J. & Kang, D. W. Bandgap engineering via doping strategies for narrowing the bandgap below 1.2 eV in Sn/Pb binary perovskites: unveiling the role of Bi3+ incorporation on different A-site compositions. Nanomaterials. 14, 1554 (2024).

Meng, X. & Zhang, Z. Facile synthesis of BiOBr/Bi2WO6 heterojunction semiconductors with high visible-light-driven photocatalytic activity. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A. 310, 33–44 (2015).

Qin, K. et al. A review of bismuth-based photocatalysts for antibiotic degradation: insight into the photocatalytic degradation performance, pathways and relevant mechanisms. Environ. Res. 199, 111360 (2021).

Aouni, A. E. & Ait Ahsaine, H. et al. Design of bismuth tungstate Bi2WO6 photocatalyst for enhanced and environmentally friendly organic pollutant degradation. Materials. 17, 1029 (2024).

Kang, Z. et al. Effect of oxygen vacancies and crystal symmetry on piezocatalytic properties of Bi2WO6 ferroelectric nanosheets for wastewater decontamination. Environ. Sci. Nano. 8, 1376–1388 (2021).

Hao, Y., Li, F., Chen, F., Chai, M. & Liu, R. X.-j. Wang, in situ one-step combustion synthesis of Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 heterojunctions with notable visible light photocatalytic activities. Mater. Lett. 124, 1–3 (2014).

Gui, M. S., Zhang, W. D., Su, Q. X. & Chen, C. H. Preparation and visible light photocatalytic activity of Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 heterojunction photocatalysts. J. Solid State Chem. 184, 1977–1982 (2011).

Obregón, S. & Colón, G. Erbium doped TiO2–Bi2WO6 heterostructure with improved photocatalytic activity under sun-like irradiation. Appl. Catal. B. 140, 299–305 (2013).

Fu, G., Xu, G., Chen, S., Lei, L. & Zhang, M. Ag3PO4/Bi2WO6 hierarchical heterostructures with enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity for the degradation of phenol. Catal. Commun. 40, 120–124 (2013).

Kanwal, S. et al. A facile green approach to the synthesis of Bi2WO6@V2O5 heterostructure and their photocatalytic activity evaluation under visible light irradiation for RhB dye removal. Arab. J. Chem. 16, 104685 (2023).

Dang Phu, N., Huy Hoang, L., Guo, P. C. & Chen, X. B. Ching Chou, study of photocatalytic activities of Bi2WO6/BiVO4 nanocomposites. J. Solgel Sci. Technol. 83, 640–646 (2017).

Liu, J., Luo, Z., Han, W., Zhao, Y. & Li, P. Preparation of ZnO/Bi2WO6 heterostructures with improved photocatalytic performance. Mater. Sci. Semiconduct. Process. 106, 104761 (2020).

Min, Y., Zhang, K., Chen, Y., Zhang, Y. & Zhao, W. Synthesis of nanostructured ZnO/Bi2WO6 heterojunction for photocatalysis application. Sep. Purif. Technol. 92, 115–120 (2012).

Xu, Z. et al. UV-induced formation of activated Bi2O3 nanoflake: an enhanced visible light driven photocatalyst by platinum loading. RSC Adv. 2, 103–106 (2012).

Peng, Y. et al. Novel one-dimensional Bi2O3–Bi2WO6 p–n hierarchical heterojunction with enhanced photocatalytic activity. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2, 8517–8524 (2014).

Wang, H. et al. Surface decoration of Bi2WO6 superstructures with Bi2O3 nanoparticles: an efficient method to improve visible-light-driven photocatalytic activity. CrystEngComm. 15, 9011–9019 (2013).

Pal, S. et al. β-Bi2O3–Bi2WO6 nanocomposite ornated with meso-Tetraphenylporphyrin: interfacial electrochemistry and photoresponsive detection of nanomolar hexavalent cr. Inorg. Chem. 62, 21201–21223 (2023).

Lianmawii, L. & Singh, N. M. Luminescence and photocatalytic degradation of Indigo Carmine in the presence of Sm3+ doped ZnS nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 13, 22450 (2023).

AbouSeada, N., Ahmed, M. & Elmahgary, M. G. Synthesis and characterization of novel magnetic nanoparticles for photocatalytic degradation of Indigo Carmine dye. Mater. Sci. Energy Technol. 5, 116–124 (2022).

Sukhadeve, G. et al. Visible light assisted photocatalytic degradation of Indigo Carmine dye and NO2 removal by Fe doped TiO2 nanoparticles. Ceram. Int. 48, 29121–29135 (2022).

Abdel-Aziz, R., Ahmed, M. & Abdel-Messih, M. A novel UV and visible light driven photocatalyst AgIO4/ZnO nanoparticles with highly enhanced photocatalytic performance for removal of Rhodamine B and Indigo Carmine dyes. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A. 389, 112245 (2020).

Channei, D. et al. Synthesis and characterization of WO3/CeO2 heterostructured nanoparticles for photodegradation of Indigo Carmine dye. ACS Omega. 6, 19771–19777 (2021).

Alsadoon, A. H., Abbas, B. I. & Fairooz, N. Y. Photo catalytic degradation of Indigo Carmine in aqueous media using nano crystalline zirconia by solid state method: synthesis and characterization.

Sukhadeve, G., Shaileshkumar, Y., Janbandhu, R. & Kumar, R. S. Gedam corrigendum: Ag-Doped TiO2 Nanoparticles as an effective photocatalyst for degradation of Indigo Carmine dye under visible light. ChemistrySelect. 7, e202200173 (2022).

Kumar, R., Janbandhu, S. Y., Sukhadeve, G. K. & Gedam, R. S. Visible light assisted surface plasmon resonance triggered Ag/ZnO nanocomposites: synthesis and performance towards degradation of Indigo Carmine dye. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 98619–98631 (2023).

Darwish, A. S., Sayed, M. A. & Shebl, A. Cuttlefish bone stabilized Ag3VO4 nanocomposite and its Y2O3-decorated form: Waste-to-value development of efficiently ecofriendly visible-light-photoactive and biocidal agents for dyeing, bacterial and larvae depollution of Egypt’s wastewater. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A. 401, 112749 (2020).

Janbandhu, S., Joshi, A., Munishwar, S. & Gedam, R. CdS/TiO2 heterojunction in glass matrix: synthesis, characterization, and application as an improved photocatalyst. Appl. Surf. Sci. 497, 143758 (2019).

Lubis, S. & Sitompul, D. W. Photocatalytic degradation of indigo carmine dye using α-Fe2O3/bentonite nanocomposite prepared by mechanochemical synthesis. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 012142 (IOP Publishing, 2019).

Lakshmi, K. D. et al. Visible light driven mesoporous Mn and S co-doped TiO2 nano material: characterization and applications in photocatalytic degradation of Indigocarmine dye and antibacterial activity. Environ. Nanatechnol. Monit. Manag. 10, 494–504 (2018).

Messih, M. A., Ahmed, M., Soltan, A. & Anis, S. S. Facile approach for homogeneous dispersion of metallic silver nanoparticles on the surface of mesoporous Titania for photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue and Indigo Carmine dyes. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A. 335, 40–51 (2017).

Ananda, S. Synthesis and characterization of Se-doped ZnO nanoparticles by electrochemical method: photodegradation kinetics of Indigo Carmine dye and study of antimicrobial, antimitotic activities of Se-doped ZnO nanoparticles. Am. Chem. Sci. J. 4, 616–637 (2014).

Ananda, S., Gowda, N. M. M. & Raksha, K. R. Synthesis of Niobium doped ZnO nanoparticles by electrochemical method: characterization, photodegradation of Indigo Carmine dye and antibacterial study. Adv. Nanopart. 3, 133 (2014).

Huy, B. T., Paeng, D. S., Thao, C. T. B., Phuong, N. T. K. & Lee, Y. I. ZnO-Bi2O3/graphitic carbon nitride photocatalytic system with H2O2-assisted enhanced degradation of Indigo Carmine under visible light. Arab. J. Chem. 13, 3790–3800 (2020).

Tho, N. T. M., Van Cuong, N., Thi, V. H. L., Thang, N. Q. & Dang, P. H. A novel n–p heterojunction Bi2S3/ZnCo2O4 photocatalyst for boosting visible-light-driven photocatalytic performance toward Indigo Carmine. RSC Adv. 13, 16248–16259 (2023).

Ge, M., Li, Y., Liu, L., Zhou, Z. & Chen, W. Bi2O3 – Bi2WO6 composite microspheres: hydrothermal synthesis and photocatalytic performances. J. Phys. Chem. C. 115, 5220–5225 (2011).

Nezamzadeh-Ejhieh, A. & Zabihi-Mobarakeh, H. Heterogeneous photodecolorization of mixture of methylene blue and bromophenol blue using CuO-nano-clinoptilolite. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 20, 1421–1431 (2014).

Abdel-Aziz, A. M., Ramadan, M., Mohsen, A. & Sayed, M. A. Thermal treatment of lead-rich dust to improve fresh characteristics and adsorption behavior of autoclaved geopolymer for methylene blue dye removal. Egypt. J. Chem. 66, 1633–1644 (2023).

Sayed, M. A., Abdelmaksoud, W., Teleb, S. M., El-Din, A. M. & Abo-Aly, M. M. Low-cost fabrication and physicochemical characterization of ZnFe2O4 nanoparticles as an efficient multifunctional inorganic pigment. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 20, 1997–2006 (2023).

Hatel, R. & Baitoul, M. Nanostructured tungsten trioxide (WO3): synthesis, structural and morphological investigations. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 012014 (2019).

Oudghiri Hassani, H. et al. Synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic activity of α-Bi2O3 nanoparticles. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 239 (2015).

Singh, S., Rawat, S., Patidar, R. & Lo, S. L. Development of Bi2WO6 and Bi2O3 – ZnO heterostructure for enhanced photocatalytic mineralization of bisphenol A. Water Sci. Technol. 86, 3248–3263 (2022).

Mandal, R. K. & Pradhan, S. K. Superior photocatalytic performance of mechanosynthesized Bi2O3–Bi2WO6 nanocomposite in wastewater treatment. Solid State Sci. 115, 106587 (2021).

Li, C. et al. Improved photocatalytic activity of Z-scheme β-Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 nanocomposites from band bending of Pn heterojunction. J. Nanopart. Res. 22, 1–11 (2020).

Wu, C. H. et al. Synthesis of Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 composites using single-step solvothermal method: determinations of surface characteristics and photocatalytic activity. Desalin. Water Treat. 151, 56–65 (2019).

Kominami, H., Murakami, S., Kato, J., Kera, Y. & Ohtani, B. Correlation between some physical properties of titanium dioxide particles and their photocatalytic activity for some probe reactions in aqueous systems. J. Phys. Chem. B. 106, 10501–10507 (2002).

Sudrajat, H. & Sujaridworakun, P. Correlation between particle size of Bi2O3 nanoparticles and their photocatalytic activity for degradation and mineralization of atrazine. J. Mol. Liq. 242, 433–440 (2017).

El-Gamal, S. M. et al. Impact of WO3-nanoparticles on the setting time and early strength for different cementitious materials. Mater. Sci. Forum Trans. Tech. Publ. 125–133 (2024).

Li, T., Quan, S., Shi, X., Yang, L. & Liu, C. Fabrication of La-doped Bi2O3 nanoparticles with oxygen vacancies for improving photocatalytic activity. Catal. Lett. 150, 640–651 (2020).

Trixy Nimmy Priscilla, D., Radha, R., Chitra, A. & Geetha, S. K. Comprehensive evaluation of nanosized bismuth tungstate (Bi2WO6) as photoanodes for photoelectrochemical water splitting performance. J. Cluster Sci. 35, 875–889 (2024).

Salari, H. Facile synthesis of new Z-scheme Bi2WO6/Bi2MoO6 p–n junction photocatalysts with high photocatalytic activity: structure, kinetics and mechanism approach. Mater. Res. Bull. 131, 110979 (2020).

Zhou, K. et al. Highly efficient photocatalytic performance of BiI/Bi2WO6 for degradation of Tetracycline hydrochloride in an aqueous phase. RSC Adv. 10, 12068–12077 (2020).

Song, Y., Zhou, F., Chai, Y. & Zhan, S. Study on high antibacterial RGO/Bi2WO 6 microspheres combined with PEVE coating for marine sterilization under visible light. Res. Chem. Intermed. 47, 2297–2310 (2021).

Dong, H., Yin, Y. & Guo, X. Synthesis and characterization of Ag/Bi2WO6/GO composite for the fast degradation of Tylosin under visible light. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 25, 11754–11766 (2018).

Low, J., Yu, J., Li, Q. & Cheng, B. Enhanced visible-light photocatalytic activity of plasmonic ag and graphene co-modified Bi2WO6 nanosheets. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 1111–1120 (2014).

Moghadam, S. A. & Farzaneh, F. Synthesis and investigation of template effects on nanoporous Bi2O3 morphologies by Sol gel method as photocatalysts for degradation of some organic dyes as water pollutants. J. Cluster Sci. 33, 495–502 (2022).

Ramadan, M., Amin, M. & Sayed, M. A. Superior physico-mechanical, fire resistivity, morphological characteristics and gamma radiation shielding of hardened OPC pastes incorporating ZnFe2O4 spinel nanoparticles. Constr. Build. Mater. 234, 117807 (2020).

Alenazi, D. A. et al. Synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic performance of W6+ impregnated g-C3N4 for the removal of Chlorophenol derivatives in natural sunlight exposure. Chemosphere. 265, 129135 (2021).

Cai, M., Liu, Y., Dong, K., Chen, X. & Li, S. Floatable S-scheme Bi2WO6/C3N4/carbon fiber cloth composite photocatalyst for efficient water decontamination. Chin. J. Catal. 52, 239–251 (2023).

Gupta, S. et al. Morphology and crystal structure dependent pseudocapacitor performance of hydrated WO3 nanostructures. Mater. Adv. 1, 2492–2500 (2020).

Palomino-Resendiz, R. et al. Analysis of the effect of cationic ratio Bi3+/Fe3+ on the magnetic and multiferroic properties of BiFeO3 nanoparticles synthesized using a sonochemical-assisted method. Ceram. Int. 48, 14746–14753 (2022).

LiS., Dong, K., Cai, M., Li, X. & Chen, X. A plasmonic S-scheme Au/MIL-101 (Fe)/BiOBr photocatalyst for efficient synchronous decontamination of cr (VI) and Norfloxacin antibiotic. EScience. 4, 100208 (2024).

Li, S. et al. Enhanced antibiotic degradation performance of Cd0.5Zn0.5S/Bi2MoO6 S-scheme photocatalyst by carbon Dot modification. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 164, 59–67 (2023).

Zhao, L. et al. Bi/Bi2O3/WO3 composite: A bifunctional plasmonic heterostructure for detection and degradation pollutions in wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10, 107643 (2022).

Wang, T., Zhang, F., Xiao, G., Zhong, S. & Lu, C. Synthesis of Bi2WO6/Bi2O3 composite with enhanced photocatalytic activity by a facile one-step hydrothermal synthesis route. Photochem. Photobiol. 91, 291–297 (2015).

Zuo, G. et al. S-scheme Bi2O3/MnS heterojunction for photocatalytic degradation of Ciprofloxacin under visible light. J. Mater. Res. 1–14 (2025).

You, C. et al. Improved photo-carrier transfer by an internal electric field in BiOBr/Nrich C3N5 3D/2D S-scheme heterojunction for efficiently photocatalytic micropollutant removal. Acta Phys. Chim. Sin. 40, 2407014 (2024).

Chang, J. et al. Oxygen vacancies enriched Bi2O3 as high capacity and high rate negative material for aqueous alkali battery. Appl. Surf. Sci. 601, 154296 (2022).

Ramadan, M. et al. Developing green slag/bentonite-based geopolymers modified with meso-porous tungsten oxide: zeolitic phases, mechanical performance and gamma-radiation mitigation. Appl. Clay Sci. 255, 107421 (2024).

Amin, M. et al. Synthesis of multifunctional mesoporous geopolymer under hydrothermal curing: high mechanical resistance and efficient removal of methylene blue from aqueous medium. Dev. Built Environ. 18, 100460 (2024).

Anastasescu, C., Mihaiu, S. & Preda, S. M. Zaharescu, 1D Oxide Nanostructures Obtained by Sol–Gel and Hydrothermal Methods (Springer, 2016).

Sayed, M. A., Abo-Aly, M., Aziz, A. A. A., Hassan, A. & Salem, A. N. M. A facile hydrothermal synthesis of novel CeO2/CdSe and CeO2/CdTe nanocomposites: spectroscopic investigations for economically feasible photocatalytic degradation of congo red dye. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 130, 108750 (2021).

Reddy, I. N. et al. Systematic studies of Bi2O3 hierarchical nanostructural and plasmonic effect on photoelectrochemical activity under visible light irradiation. Ceram. Int. 45, 16784–16791 (2019).

Viezbicke, B. D., Patel, S., Davis, B. E. & Birnie, D. P. Evaluation of the Tauc method for optical absorption edge determination: ZnO thin films as a model system. Phys. Status Solidi (b). 252, 1700–1710 (2015).

Babitha, K., Sreedevi, A., Priyanka, K., Sabu, B. & Varghese, T. Structural characterization and optical studies of CeO2 nanoparticles synthesized by chemical precipitation. Indian J. Pure Appl. Phys. (IJPAP). 53, 596–603 (2015).

Devi, K. S. et al. Modelling and optimization of Rhodamine B degradation over Bi2WO6–Bi2O3 heterojunction using response surface methodology. Appl. Nanosci. 13, 3749–3765 (2023).

Katubi, K. M. et al. The correlation of bandgap with the crystallite size using the quantum confinement effect for wastewater treatment. Desalin. Water Treat. 101115 (2025).

Hu, W., Wu, F. & Liu, W. Construction of S-scheme heterojunction by doping Bi2WO6 into Bi2O3 for efficiently enhanced visible-light photocatalytic performance. J. Mater. Sci. 57, 4265–4282 (2022).

Wei, Y. L. et al. Porous and visible-light-driven p–n heterojunction constructed by Bi2O3 nanosheets and WO3 microspheres with enhanced photocatalytic performance. Sep. Purif. Technol. 256, 117815 (2021).

Haghighi, P., Alijani, S., Bazyari, A. & Thompson, L. T. Visible light dye degradation over fluorinated mesoporous TiO2 – WO3 – Bi2O3/SiO2 nanocomposite photocatalyst-adsorbent using immersion well reactor. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A. 426, 113790 (2022).

Hu, W., Wu, F. & Liu, W. Facile synthesis of Z-scheme Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 composite for highly effective visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of nitrobenzene. Chem. Phys. 552, 111377 (2022).

Dong, S. et al. Interfacial and electronic band structure optimization for the adsorption and visible-light photocatalytic activity of macroscopic ZnSnO3/graphene aerogel. Compos. Part. B Eng. 215, 108765 (2021).

Li, H., Zhou, Y., Tu, W., Ye, J. & Zou, Z. State-of‐the‐art progress in diverse heterostructured photocatalysts toward promoting photocatalytic performance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25, 998–1013 (2015).

Chen, T. et al. A honeycomb multilevel structure Bi2O3 with highly efficient catalytic activity driven by bias voltage and oxygen defect. Appl. Catal. B. 237, 442–448 (2018).

Chen, A., Lu, G., Tao, Y., Dai, Z. & Gu, H. Novel photocatalyst immobilized on springs and packed photoreactor. Mater. Phys. Mech. 4, 121–124 (2001).

Enesca, A. & Isac, L. The influence of light irradiation on the photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants. Materials. 13, 2494 (2020).

Yuan, R., Ramjaun, S. N., Wang, Z. & Liu, J. Photocatalytic degradation and chlorination of Azo dye in saline wastewater: kinetics and AOX formation. Chem. Eng. J. 192, 171–178 (2012).

Qi, L., Yu, J. & Jaroniec, M. Enhanced and suppressed effects of ionic liquid on the photocatalytic activity of TiO2. Adsorption. 19 557–561 (2013).

Dong, C., Fang, W., Yi, Q. & Zhang, J. A comprehensive review on reactive oxygen species (ROS) in advanced oxidation processes (AOPs). Chemosphere. 308, 136205 (2022).

Rezaei, M., Nezamzadeh-Ejhieh, A. & Massah, A. R. A comprehensive review on the boosted effects of anion vacancy in the heterogeneous photocatalytic degradation, part II: focus on oxygen vacancy. ACS Omega. 9, 6093–6127 (2024).

Wang, P. et al. In-situ growth of Ag3VO4 nanoparticles onto BiOCl nanosheet to form a heterojunction photocatalyst with enhanced performance under visible light irradiation. J. Alloys Compd. 688, 1–7 (2016).

Sheng, J., Li, X. & Xu, Y. Generation of H2O2 and OH radicals on Bi2WO6 for phenol degradation under visible light. ACS Catal. 4, 732–737 (2014).

Zhou, L. et al. In situ oxidation of ethylene glycol coupled with Bi2O3 epitaxial growth to prepare Bi2O3/BiOCOOH heterojunctions with oxygen vacancies for efficient photocatalytic lignin degradation. Colloids Surf. A. 664, 131134 (2023).

Zeng, T. et al. In-situ construction of oxygen vacancies-rich direct Z-scheme δ-Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 heterojunction for enhanced photocatalytic N2 fixation. J. Alloys Compd. 975, 172851 (2024).

Khadhraoui, M., Trabelsi, H., Ksibi, M., Bouguerra, S. & Elleuch, B. Discoloration and detoxicification of a congo red dye solution by means of Ozone treatment for a possible water reuse. J. Hazard. Mater. 161, 974–981 (2009).

Hitam, C. & Jalil, A. A review on exploration of Fe2O3 photocatalyst towards degradation of dyes and organic contaminants. J. Environ. Manage. 258, 110050 (2020).

Jamil, S. et al. Photocatalytic degradation of Indigo Carmine dye by hydrothermally synthesized graphene nanodots (GNDs): investigation of kinetics and thermodynamics. RSC Adv. 14, 23973–23986 (2024).

Bonelli, B., Freyria, F. S., Rossetti, I. & Sethi, R. Nanomaterials for the Detection and Removal of Wastewater Pollutants (Elsevier, 2020).

Nagaraja, R., Kottam, N., Girija, C. & Nagabhushana, B. Photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B dye under UV/solar light using ZnO nanopowder synthesized by solution combustion route. Powder Technol. 215, 91–97 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work is based on work supported by the Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) under grant number 46044. The authors would like to extend a special acknowledgment to STDF to support this research.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A.S.: Conceptualization, methodology, visualization, resources, formal analysis, data curation, validation, writing-review and editing. S.M.A.E.-G.: Conceptualization, investigation, writing-review and editing, project administration. M.R.: Conceptualization, visualization, resources. F.M.H.: Methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation. A.M.: Conceptualization, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, writing-review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sayed, M.A., El-Gamal, S.M.A., Ramadan, M. et al. Hydrothermal synthesis and structural optimization of Bi2O3/Bi2WO6 nanocomposites for synergistic photodegradation of Indigo Carmine dye. Sci Rep 15, 17260 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01925-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01925-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Structural and Optical Engineering of Bi2O3 Nanostructures for Enhanced Visible-Light Photocatalysis

Catalysis Letters (2026)

-

Hollow flower-like Cu2(OH)3Cl/Cu2O nanostructures and their efficient catalytical properties

Applied Physics A (2025)