Abstract

Coal seam drilling for pressure relief is one of the most widely adopted measures to mitigate rock bursts. However, conventional drilling methods exhibit limited effectiveness in hard coal seams and may compromise the integrity of roadway support structures. To optimize traditional pressure relief drilling parameters, this study investigated the influence of coal seam strength and borehole diameter on pressure relief efficiency based on elastoplastic mechanics theory. A novel mechanical reaming technology for pressure relief and rock burst prevention in hard coal seams was developed and subjected to field trials. Multiple monitoring techniques were employed to evaluate its performance in terms of both pressure relief and support stability. The conclusion was drawn that: (1) The higher the strength of the coal seam, the smaller the radius of the plastic zone of the borehole; therefore, the pressure relief effect of the borehole in the hard coal seam is poor. After increasing the diameter of the borehole, the radius of the plastic zone increases, but when the diameter of the borehole increases to 300 mm, the increasing trend of the radius of the plastic zone weakens. Thus, only increasing the diameter of the borehole cannot improve the pressure relief effect of the borehole without limit. (2) An innovative hard coal seam pressure relief and anti-impact technology, termed support, deep pressure relief, unloading-support coupling, the elastic energy accumulated in the coal body through a deep large borehole while utilizing a shallow small borehole to maintain the bearing capacity of the support structure, thereby achieving a balance between pressure relief and support. (3) In comparison to conventional drilling areas, the volume of coal seam drilling powder in the mechanical reaming area has increased by 3.1 times, and the number of per meter has risen by 70%, significantly enhancing the pressure relief effect. Additionally, the anchoring force of the roof anchor cable in the mechanical reaming area has decreased by up to 29%, the variation in tension of the anchor cable on the sides has been reduced by up to 51.8%, the convergence of the two sides of the roadway has diminished by up to 63%, the convergence between the roof and floor has decreased by up to 51%, and both the stress on the support structure and the deformation of the surrounding rock have been significantly reduced. These research findings provide a theoretical foundation and technical support for the prevention and control of rock bursts in similar hard coal seam mining roadways.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rock burst is a dynamic phenomenon caused by the instantaneous release of elastic energy accumulated in the coal and rock mass around the roadway or working face in the process of underground mining1,2,3. A large number of practices show that the prevention and control of rock bursts is essentially to control the high-stress state of coal and rock mass, reduce the strength of coal and rock mass, and increase its plastic characteristics4,5. Borehole pressure relief in coal seams is one of the most commonly used means to prevent and control rock bursts. Its essence is to form a weakening zone inside the coal body, redistribute the stress of the coal body, transfer the peak stress position to the deep part of the coal body, and effectively weaken the bearing capacity of the coal body, thus reducing the storage capacity of the elastic strain energy of the rock mass and the rock burst tendency5.

There has been a lot of research on the pressure relief and anti-impact technology of coal seam drilling. Jia et al.5,6,7 studied the influence of drilling parameters on the strength and failure mode of the sample through laboratory tests and numerical simulation. The results show that the expansion and penetration of cracks around the borehole are the main reasons for pressure relief. Zhang et al.8 studied the strength, energy dissipation index, crack propagation, and local crack initiation and propagation process of the sample. It was found that the drilling density had a significant effect on the development of local cracks, and the pressure relief density was positively correlated with the pressure relief effect of the drilling. Wen et al.9 used a numerical simulation method to study the process of borehole pressure relief in rock burst roadways and found that the main factors affecting the effectiveness of borehole pressure relief include borehole diameter and borehole spacing. Mishra et al.10 measured the stress change process of borehole pressure relief on site, indicating that the stress change of surrounding rock after drilling shows three-stage characteristics. This indicates that large-diameter boreholes can provide sufficient space for surrounding rock deformation and improve pressure relief efficiency. Through the construction of large-diameter pre-pressure relief boreholes with a diameter of 120 mm, a hole depth of 25 m, and a spacing of 1 m, the pressure relief protection zone formed by Zhu Sitao11 and others alleviates the rock burst and large deformation problems of roadways along thick coal seams.

However, the traditional drilling pressure relief technology also has some limitations. Pan Junfeng et al.12,13 studied the pressure relief effect of boreholes under the condition of incremental static load, such as advance abutment pressure of the working face, by means of indoor experiments and numerical simulations. It was found that with the increase in stress concentration, the range of the pressure relief area and the pressure relief amplitude of the borehole gradually decreased, the volume of the plastic zone of the surrounding rock of the borehole gradually decreased, and the pressure relief effect of the borehole decreased. Zhang Dongxiao et al.14 studied the pressure relief effect and energy release law of coal seam boreholes under different coal seam thickness conditions. It was found that with the increase in coal seam thickness, measures such as reducing borehole spacing and increasing borehole diameter should be taken to achieve a better pressure relief effect. Miao Chen et al.15 also carried out finite compression experiments on samples with different borehole diameters, reaming lengths, and spacings. The results show that increasing the borehole diameter and reaming length while reducing the borehole spacing can increase the dissipated strain energy, thereby achieving a better pressure relief effect. In field practice, many scholars have achieved a good anti-scour effect by optimizing the drilling pressure relief parameters. Tan et al.17 studied the mechanism of instability and rock burst in deep coal roadways and found that the prevention and control of rock bursts should start from two aspects: ‘unloading’ and 'solid.' Through shallow reinforcement and deep drilling pressure relief, the stability of the roadway surrounding rock is protected. Gao Mingshi et al.18 studied the combined technology of support-external unloading of built-in casing, repeatedly cutting cracked coal bodies, and active support of anchor cables, which effectively maintained the stability of the roadway surrounding rock. Liu Guolei et al.19 proposed a three-stage reconstruction and anti-scour technology scheme for surrounding rock in high-stress difference zones, including fracturing reconstruction, water injection modification, and drilling pressure relief, which reduced the impact risk of deep coal roadways. Wu Yongzheng et al.20 considered that the deep rock burst roadway should take measures in coordination, which could improve the effect of drilling pressure relief and reduce the overall deformation of the surrounding rock of the roadway. Xie Shengrong et al.21 studied the deformation characteristics of deep soft broken coal roadways under the influence of strong mining and proposed the collaborative control technology of external anchoring and internal unloading in large-section coal roadways. It shows that the pressure relief of large holes in the peak area of internal stress on both sides of the coal body can promote the transfer of coal and rock deformation to the pressure relief hole group and maintain the long-term stability of large-section coal roadways.

Throughout the above research, the academic and engineering circles have paid attention to the fact that the conventional coal seam drilling pressure relief technology cannot take into account the pressure relief and support effects and have put forward targeted improvement methods. However, there are few studies on the influence of coal seam strength on the drilling pressure relief effect, especially on the effect of reaming pressure relief. In addition, the hard coal seam is an important geological feature of rock bursts. The application scenarios of the above research are mainly concentrated in ordinary coal seams, and there are few studies on the application effect of reaming pressure relief technology in hard coal seams. To comprehensively examine the impact of segmented reaming and drilling pressure relief technology on the prevention and management of rock bursts in hard coal seams, this study employed a combination of theoretical analysis, numerical simulation, and other methodologies. The investigation focused on the effects of coal seam strength and borehole diameter on the efficacy of drilling pressure relief. A novel technology for segmented reaming and pressure relief in hard coal seams, based on mechanical reaming principles, was developed, followed by an industrial test of this approach. The effectiveness of pressure relief and support mechanisms was assessed through various methods, and the efficacy of rock burst prevention was validated. The findings of this research provide a theoretical foundation and technical guidance for the prevention and control of rock bursts in roadways within hard coal seams exhibiting similar characteristics.

Characteristics of borehole pressure relief in hard coal seam

The uniaxial compressive strength is the most direct indicator of coal hardness. The identification reports of the burst tendency of the main coal seams of 40 coal mines in the main rock burst mining areas, such as Ludong, Luzhong, Luxi, Henan Yima, Shaanxi Binchang, and Ordos in China, were collected, and the uniaxial compressive strength index of the coal seam was counted. The statistical results are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1. It is found that the uniaxial compressive strength of the main coal seam in the Ordos area is generally greater than 25 MPa, reaching up to 35 MPa, which is higher than that of rock burst mines in Shandong, Henan and Shaanxi, and ranks first in the main rock burst mines in China.

Coal seam drilling pressure relief is the most commonly used pressure relief method in the Ordos area. The area is generally constructed according to the national standard of 'Rock Burst Measurement, Monitoring and Prevention Method (GB/T 25217.10).' The diameter of the borehole is 150–200 mm, and the depth of the borehole is 15–25 m. However, due to the influence of hard coal seam conditions, the traditional pressure relief method has the following limitations in field practice:

-

1.

The occurrence of drilling collapse is infrequent. Taking the Menkeqing Coal Mine as a case study, borehole collapse is seldom observed beyond a distance of 70 m from the working face, and instances of collapse are notably absent within the advanced influence zone, as illustrated in Fig. 2a.

-

2.

Shear failure is likely to occur. As depicted in Fig. 2b, when a borehole collapses, lateral splitting is commonly observed approximately 1 m within the orifice, accompanied by the formation of a separation layer between the coal mass and the surface of the roadway.

-

3.

The area affected by the orifice damage is substantial. As shown in Fig. 2c, the collapse of the borehole is characterized by abrupt brittle failure rather than plastic deformation, which can lead to a 'blow-out’ phenomenon, posing a significant risk of damage to the roadway support structure.

-

4.

Repeated pressure relief is required. Due to the large strength of the coal body and the difficulty of pressure relief, the mine often needs to carry out high-density, multi-round large-diameter drilling pressure relief work. Repeated pressure relief is likely to cause roadway support failure, as shown in Fig. 2d.

In conclusion, the analysis indicates that while pressure relief techniques for coal seam drilling in the Ordos region are extensively implemented, their effectiveness remains suboptimal. Therefore, enhancing the pressure relief outcomes of drilling in hard coal seams and reducing the detrimental impact of drilling on foundational support constitutes a significant area for further investigation.

Theoretical analysis of drilling pressure relief mechanism in hard coal seam

Radius analysis of the plastic zone around the borehole

In accordance with the principles of classical elastic mechanics, a drilling mechanics model has been developed for a non-uniform pressure stress field. It is posited that the coal matrix adheres to conditions of continuity, uniformity, and isotropy, while also conforming to the Mohr–Coulomb strength criterion. The rock mass at an infinite distance around the R0 borehole is in a two-way unequal pressure state, which is subjected to vertical stress P, horizontal stress kP, and plastic zone radius Rp, as shown in Fig. 3.

The expression for the stress surrounding the borehole in polar coordinates is presented in Eq. (1), and the stress at any point in the model can be determined by r and θ22.

In the formula: p is the initial in-situ stress; K represents the lateral pressure coefficient associated with the specific location of the coal body; R0 is the borehole radius; σr is the radial stress of coal at point (r,θ); σθ is the tangential stress of coal at point (r,θ); τrθ is the shear force of coal at point (r,θ).

Substituting θ = 0° into Eq. (1), the tangential stress of the elastic surrounding rock on the horizontal axis is

When k ≠ 1, the total load of elastic surrounding rock on the horizontal axis is:

In the event that the borehole undergoes plastic deformation, the stress distribution will display characteristics indicative of the simultaneous presence of both elastic and plastic states. When k ≤ 1, Fig. 4 illustrates the elastic–plastic tangential stress and the elastic tangential stress of the surrounding rock in the borehole at an angle of θ = 0°.

The cumulative load exerted by the surrounding rock of the borehole along the horizontal axis can be documented as:

In the formula: \(\sigma_{{\theta (r \le R_{s} )}}\) and \(\sigma_{{\theta (r > R_{s} )}}\) are the tangential stress of the plastic zone and the elastic zone around the borehole on the horizontal axis, MPa.

Studies have shown that23,24, Under non-isobaric conditions, the stress distribution along the horizontal axis of the plastic zone remains uniform.

For the stress in the elastic zone, the tangential stress \(\sigma_{{\theta (r \le R_{s} )}}\) of the elastic zone of the surrounding rock at θ = 0° still obeys formula (2), that is,

The stress at the elastic–plastic interface must satisfy the yield criterion, while the shear stress of the surrounding rock in the horizontal axis direction is assumed to be zero. Therefore, r = Rs1 can be substituted into the above parallel M-C criterion equation to obtain:

In order to describe the σθ-r relation of surrounding rock in the elastic zone, the formula (6) is rewritten as

In the formula, F(r) is a function of r; the physical meaning of σθ is shown in Fig. 4, which is the stress difference between the stress at the elastic–plastic junction of the surrounding rock on the horizontal axis and P, MPa.

By combining Fig. 4 and Formula (8), it can be seen that when r = Rs1, F(r) = 1. Therefore, r = Rs1 is substituted into Formula (6), and F(r) = 1 is substituted into Formula (8), and then the two formulas are solved simultaneously:

Combining Eqs. (6), (7), and (8), the expression for F(r) can be obtained as:

Therefore, the tangential stress in the elastic zone of surrounding rock at θ = 0° can be expressed as

In the formula, σθ|r=Rs = Rs is the tangential stress at the elastic–plastic interface on the vertical axis of the surrounding rock, in MPa. Its expression can also be solved according to the condition of a uniform stress field:

Finally, the total load of elastic–plastic surrounding rock on the vertical axis can be obtained by substituting formula (5), formula (11), and formula (12) into formula (4). According to the law that the total load is constant, the total load formula (3) of elastic surrounding rock is solved; that is, when k ≤ 1, the approximate solution of Rs1 is.

Similarly, when plastic deformation occurs in the borehole under the condition of k > 1, as shown in Fig. 5, the radius of the plastic zone on the vertical axis, Rs2, must not be 0, and the tangential stress of the surrounding rock on the vertical axis will have elastic and plastic stress states. Rs2 can be derived by using the law of constant total load on the vertical axis and the stress formula of the plastic zone in a uniform stress field.

Analysis of influencing factors of drilling pressure relief effect

Assuming that the surrounding rock exhibits a continuous transition to an ideal plastic state, the Mohr envelope representing plastic deformation is characterized as a linear function. This linearity is defined by the parameters of cohesion (c) and the internal friction angle (φ), as illustrated in Fig. 6.

The plastic condition derived from the Mohr stress circle at the limit state is22,23:

By substituting Eq. (1) into the plastic condition outlined in Eq. (15), one can derive the implicit equation that defines the boundary of the plastic zone surrounding the borehole in terms of the variables r and θ.

The boundary equation that delineates the transition between the elastic zone and the plastic zone of the surrounding rock near the borehole can be derived when f (r, θ) equals zero. From Eq. (16), it is known that the main factors affecting the plastic zone are the lateral pressure coefficient, coal strength, and borehole diameter. This study examines the influence of coal strength and borehole diameter on the extent of the plastic zone for a specific roadway, assuming that the lateral pressure coefficient remains constant.

Influence of coal strength

Because it is very difficult to sample and test coal seams with different strength conditions in different mines, in order to obtain the mechanical parameters of coal bodies with different hardness, the test reports of physical and mechanical parameters of the main coal seams in six mines in China were collected, and the cohesion, internal friction angle, compressive strength, shear strength, and other parameters of coal samples were statistically analyzed. The statistical results are shown in Table 2.

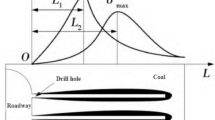

Assuming that the above six kinds of coal samples are in the same geological conditions, set P = 16 MPa, k = 0.4, R0 = 0.2 m. The six groups of c and φ values in Table 1 are substituted into formula (16) for calculation, and the plastic zone boundary curve around the borehole is obtained, as shown in Fig. 7.

It can be seen from Fig. 7 that with the increase of uniaxial compressive strength of the coal seam, the boundary of the borehole plastic zone undergoes three characteristic stages of ' butterfly-ellipse-circular ', and the maximum plastic zone radius decreases gradually with the increase of uniaxial compressive strength of the coal seam. The relationship between the radius of the maximum plastic zone in Fig. 7 and the uniaxial compressive strength and uniaxial shear strength of coal is obtained, as shown in Fig. 8.

From Fig. 8, it can be seen that the maximum plastic zone radius of the borehole is negatively correlated with the uniaxial compressive strength and shear strength of the coal and rock mass, indicating that the higher the strength of the coal body, the stronger the ability of the coal body near the hole wall to resist damage, and the smaller the plastic zone radius of the borehole, the worse the effect of drilling pressure relief.

The influence of borehole diameter

Similarly, set P = 16 MPa, k = 0.4, c = 2 MPa, φ = 25°, substitute the parameters into Eq. (16), change the value of borehole diameter R0, and calculate the plastic zone boundary curve around the borehole when R0 = 0.2–0.5 m, as shown in Fig. 9.

It can be seen from Fig. 9 that as the diameter of the borehole increases, the boundary of the plastic zone around the borehole is always distributed in a ' butterfly ' shape, and the radius of the maximum plastic zone gradually increases. At the same time, when the borehole diameter increases to 300 mm, the increasing trend of the plastic zone radius is weakened.

The above P, k, c, φ values are substituted into Eqs. (11)–(14), and the radial stress σr and tangential stress σθ curves of the borehole are calculated when R0 = 0.2 m, 0.3 m, and 0.4 m, respectively, as shown in Fig. 10. According to the quantitative analysis of Fig. 10, it is found that when the borehole diameter increases from 200 to 300 mm, the radius of the plastic zone increases by 0.43 m, while when the borehole diameter increases from 300 to 400 mm, the radius of the plastic zone only increases by 0.26 m. This suggests that merely increasing the diameter of the borehole does not unlimitedly improve the pressure relief effect of the borehole.

Mechanical reaming and pressure relief technology in hard coal seams

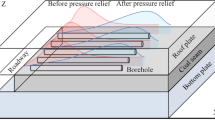

To ensure the stability of the surrounding rock within the roadway, it is essential to dissipate the elastic energy accumulated in the coal mass while also preserving the load-bearing capacity of the support structure. This necessitates establishing a balance between pressure relief and support mechanisms. The advancement of technologies related to the coupling of unloading support for hard coal seams, which incorporates reaming pressure relief and anti-scour techniques, can be summarized in the support and deep pressure relief anti-scour methodology, as illustrated in Fig. 11.

-

1.

Shallow support is defined as a circular borehole that encompasses the entire roadway, with the surrounding coal body divided into three distinct zones: a fracture zone, a plastic softening zone, and an elastic zone. The primary focus of the support system is on the fracture zone and the plastic softening zone, while the peak stress region is not emphasized. Additionally, the drilling diameter and density are not prioritized. As a result, only conventional large-diameter drilling techniques are utilized to maintain the integrity of the shallow support structure of the roadway.

-

2.

Deep pressure relief involves modifying the ‘elastic core’ region of the coal body that is subjected to peak stress. This is achieved by enlarging the borehole diameter through reaming and pressure relief techniques, which facilitates the transition of a larger section of the coal body from the elastic zone to the plastic zone. This process results in a significant release of elastic energy, effectively reducing the total elastic energy stored within the ‘elastic core’ area of the hard coal body. The ultimate objective of this intervention is to achieve pressure relief and mitigate the risk of erosion.

The implementation of shallow hole support, deep hole expansion, and pressure relief techniques effectively reduces the level of stress concentration at the initial stress peak. This process also facilitates the relocation of the stress peak to deeper regions of the solid coal, thereby achieving the objectives of cutting and pressure redistribution. Concurrently, by maintaining the support strength of the surrounding rock, the deformation of the roadway’s surrounding rock is minimized, which enhances the overall impact resistance of the roadway.

Numerical simulation of unloading-support coupling anti-scour in hard coal seam

The unloading-support coupling mechanism for reaming pressure relief

To elucidate the unloading-support coupling anti-scour mechanism associated with hard coal seams and to assess the impact of critical parameters such as borehole diameter, reaming diameter, and reaming point position on anti-scour efficacy, this study utilizes the engineering geological conditions of the Menkeqing 3106 working face as its research context. Layered modeling is conducted in accordance with the physical and mechanical properties of various rock strata, and FLAC3D is employed to simulate the changes in the stress field and displacement field of the surrounding rock in the roadway during the pressure relief process. A three-dimensional model that reflects the actual working conditions is presented in Fig. 12.

The dimensions of the model are defined as follows: length (Y) × width (X) × height (Z) = 45 m × 8 m × 15 m. A borehole is drilled in the positive direction of the Y-axis, utilizing the Mohr–Coulomb plastic strength criterion for analysis. A brick element is employed to represent both the coal seam and the surrounding rock. Horizontal movement is constrained on both lateral sides of the model, while vertical movement is restricted at the base. A vertical stress of 17 MPa is applied to the upper section, corresponding to the burial depth of the coal seam, and a lateral pressure coefficient of 0.8 is implemented based on the results of ground stress testing (According to the Menkeqing coal mine ground stress test report.). The physical and mechanical parameters of coal and rock mass used in simulation calculation and analysis are shown in Table 3 (according to the identification report of coal and rock burst tendency of the 3-1 coal seam in Menkeqing Coal Mine).

Following the initial calibration of the model, simulations were conducted to analyze the stress and deformation characteristics of the surrounding rock during roadway excavation, conventional drilling, and unloading support coupling reaming excavation. The dimensions of the roadway were established at 5 m × 5 m. After the excavation process, a cable bolt unit was incorporated into the roadway, characterized by a bolt diameter of Φ22 mm and a length of 2500 mm, with full anchorage. The arrangement consisted of a row spacing of 1 m × 1 m, with 12 bolt units allocated per row, and an initial anchoring force set at 60 kN. Following the installation of the bolts, simulations were performed for both conventional borehole excavation and unloading-branch coupling reaming excavation. The conventional borehole was designed with a diameter of 150 mm, while the reaming borehole had a diameter of 350 mm, positioned 6 m from the coal wall, with a borehole spacing of 1 m. The vertical stress distribution and the expansion of the plastic zone within the coal seam are illustrated in Fig. 13.

It can be seen from Fig. 13a that after the excavation of the roadway, the ‘elastic core’ area is generated due to the stress concentration at the position of 6 m in the coal wall. After the conventional drilling pressure relief, the area of the ‘elastic core’ is reduced, but the ‘elastic core’ area between the borehole and the roof still exists, and the degree of stress concentration is not significantly reduced. After taking deep reaming excavation, the area of the ‘elastic core’ is reduced to nearly disappear, and the degree of stress concentration is significantly reduced. From Fig. 13b, after pressure relief by deep reaming, the plastic zone between boreholes is obviously expanded, which indicates that the pressure relief effect of the borehole is enhanced, while the plastic zone on the roadway side is about 1 m. Compared with the conventional boreholes, there is no obvious change, and the coal wall still has a certain support strength, indicating that the unloading-support coupling pressure relief has a relatively small disturbance to the roadway surface support structure.

The influence of reaming parameters on the effect of pressure relief support

From the numerical simulation results, it can be seen that for the unloading-support coupling reaming pressure relief method, the shallow borehole diameter has a great influence on the roadway support effect, while the deep borehole diameter has a great influence on the coal pressure relief effect. Therefore, in order to quantitatively reveal the influence of deep and shallow borehole diameters on roadway support and pressure relief effects, three sets of numerical simulations were carried out using the control variable method: ① The fixed shallow borehole diameter is 150 mm, the deep borehole diameter is 350 m, and the borehole spacing varies from 1 to 3 m.② The fixed borehole spacing is 1 m, the deep borehole diameter is 350 mm, and the shallow borehole diameter changes from 100 to 200 mm.③ The distance between fixed boreholes was 1 m, the diameter of shallow boreholes was 150 mm, and the diameter of deep boreholes varied from 200 to 400 mm.

Influence of borehole spacing

Borehole spacing has a decisive influence on the effect of reaming pressure relief. The vertical stress distribution nephogram of the coal seam under different borehole spacing conditions is drawn, as shown in Fig. 14.

From the analysis of Fig. 14, it can be seen that when the borehole spacing is 1 m, a continuous low-stress pressure relief arch shell is formed between the boreholes, and the pressure relief effect is better in the stress peak area near the roadway side. When the borehole spacing increases to 2 m, the height of the pressure relief arch shell and the pressure relief area between the holes gradually decrease. After the borehole spacing increases to 3 m, a continuous pressure relief arch shell cannot be formed between the boreholes, and the pressure relief effect is further reduced. The variation curve of vertical stress of the coal seam under different borehole spacing is drawn as shown in Fig. 15.

According to the analysis of Fig. 15, with the increase in borehole spacing, the stress of the coal body between holes increases. When the spacing is 1 m, 2 m, and 3 m, the peak values of vertical stress between holes are 11.8 MPa, 14.6 MPa, and 22.7 MPa, respectively. When the borehole spacing increases from 1 to 2 m, the peak stress between the holes increases by 23%. When the borehole spacing increases from 2 to 3 m, the peak stress between the holes increases by 55%. It can be seen that reducing the borehole spacing helps to form a continuous weakening pressure relief zone around the borehole and improves the pressure relief effect of the borehole. Under the condition of a hard coal seam, the spacing of reaming pressure relief boreholes should not exceed 2 m.

The influence of shallow borehole diameter

The diameter of the shallow borehole has a direct influence on the coal support of the roadway side. The curves of the deformation of the surrounding rock and the effective binding force of the bolt are extracted respectively when the diameter of the shallow borehole changes, as shown in Fig. 16.

The analysis of Fig. 16a reveals that as the diameter of the shallow borehole increases, there is a corresponding gradual increase in the deformation of both the roof and floor of the roadway. Conversely, the deformation of the lateral sides initially decreases before subsequently increasing. Specifically, when the borehole diameter ranges from 100 to 130 mm, the deformation of the roadway’s lateral sides is slightly lower compared to scenarios without pressure relief. This phenomenon can be attributed to the pressure relief effect of the borehole, which alleviates stress concentration within the coal body and subsequently reduces the deformation of the surrounding rock in the roadway. However, once the diameter of the shallow borehole exceeds 130 mm, the deformation of the lateral sides escalates rapidly. For instance, at a borehole diameter of 200 mm, the deformation of the lateral sides can reach 429.3 mm, representing an increase of 49.3% compared to conditions without pressure relief. Furthermore, the analysis presented in Fig. 16b reveals that as the diameter of the shallow borehole increases, the effective binding force between the lateral sides and the roof bolt progressively diminishes, with the rate of decline accelerating in tandem with the borehole diameter. This analysis underscores that once the diameter of the shallow borehole exceeds 130 mm, larger diameters exacerbate damage to the roadway support structure, thereby complicating the control of roadway deformation.

The influence of deep borehole diameter

The curves of vertical stress and peak stress of the coal body when the diameter of the deep borehole changes are extracted, as shown in Fig. 17.

The analysis of Fig. 17a indicates that as the diameter of the deep borehole increases, the vertical stress distribution within the coal body maintains a consistent pattern. Specifically, the peak stress observed on the shallow side of the roadway exhibits a gradual decline, while the peak stress on the deep side shows a corresponding increase. According to Fig. 17b, from the perspective of stress increase, when the diameter of the deep borehole increases from 200 to 300 mm, the peak stress in the shallow region decreases from 14.48 to 9.41 MPa, a reduction of 5.07 MPa. Conversely, when the borehole diameter increases from 300 to 400 mm, the peak stress in the shallow region decreases only by 0.1 MPa, while the peak stress in the deep region increases from 9.08 to 9.72 MPa, an increase of 0.64 MPa. This trend is consistent with the theoretical analysis presented in Sect. 2.2. It also indicates that when the borehole diameter reaches 300 mm, the pressure relief effect from further increasing the diameter of the reaming diminishes, resulting in the formation of a new stress concentration zone at the bottom of the borehole.

Engineering practice of mechanical reaming and pressure relief in hard coal seam

Engineering test situation

The Menkeqing Coal Mine in the Ordos region has been selected as the engineering test site. The 3106-working face of the Menkeqing Coal Mine is characterized as a side-free face. The primary coal seam, designated as 3-1, exhibits a significant tendency for impact, with a uniaxial compressive strength of 33.54 MPa. During the excavation and mining operations of the 3106-return airway, numerous substantial energy events exceeding 105 J have been recorded, along with frequent occurrences of coal gun phenomena. Notably, there is pronounced deformation of the roadway side drum, which increases the risk of impact. Conventional large-diameter boreholes have proven ineffective in achieving adequate pressure relief in this context. To enhance the pressure relief efficacy of the coal body, an industrial test involving unloading-support coupling anti-scour techniques was conducted at the 3106 working face.

As shown in Fig. 18a, the test site is selected at a distance of 579 m to 649 m away from the retracement channel of the 3106-return airway, and the mining position of the advanced working face is 700 m, so as to avoid the influence of the advanced abutment pressure. During the excavation in this area, no borehole pressure relief was carried out on both sides of the roadway, the support was not damaged, and the integrity of the coal wall was good. A total of three different pressure relief parameters of ABC were set up for comparative tests, as follows:

A area: construction range of 20 m, mechanical reaming with pressure relief, drilling spacing of 1 m, and a hole depth of 20 m. Sectional reaming is employed, commencing at a depth of 7 m, while leaving 1 m for every 2 m. The diameter of the shallow borehole is 150 mm, and the diameter of the deep borehole is 350 mm.

Area B: construction range of 20 m, mechanical reaming and pressure relief, drilling spacing of 2 m, the remaining parameters unchanged.

C area: construction range is 30 m, conventional large diameter drilling pressure relief, drilling spacing is 2 m, drilling depth is 20 m, drilling diameter is 150 mm.

The mechanical reaming tool is used in the field. The tool adopts hydraulic control. It automatically opens under high-pressure hydraulic action, closes under low pressure, and retreats during rotary cutting reaming, as illustrated in Fig. 18b. The location and field photographs of the reaming experiment are presented in Fig. 18a,c.

Pressure relief effect test

In order to test the effect of the mechanical reaming method on the release of elastic energy accumulated in the coal body, the amount of drilling powder produced per meter during drilling in each borehole in the three regions of A, B, and C, as well as the number of ‘coal gun’ events produced per meter, were counted respectively, as shown in Figs. 19 and 20.

As illustrated in Fig. 19, the maximum quantity of pulverized coal per meter in the reaming section (7–20 m) can reach 225 kg/m, which is 3.1 times greater than that observed in conventional large-diameter boreholes measuring 150 mm. This finding indicates that mechanical reaming significantly enhances the radius of the borehole’s plastic zone, thereby markedly improving the pressure relief effect within the coal body. Figure 20 illustrates that the region between 7 and 14 m within the coal wall represents the zone of maximum stress within the coal body. When conventional drilling techniques are employed for pressure relief, an average of 2.37 ‘coal shots’ are produced per meter in this range. In contrast, the application of mechanical reaming for pressure relief results in an average of 3.69 and 4.06 ‘coal shots’ per meter in areas A and B, respectively, indicating a 70% increase in the number of 'coal shots.' This finding suggests that mechanical reaming facilitates the collapse and failure of the coal body in areas of stress concentration, significantly releasing the elastic energy that has accumulated within the coal body and enhancing the effectiveness of pressure relief.

In order to test the pressure relief effect of the mechanical reaming method on the static load in the coal body, three sets of 7-order deep and shallow hole stress gauges were constructed on the front side of the 3106 return airway. The depths of the stress gauges were 2 m, 4 m, 6 m, 8 m, 10 m, 12 m, and 14 m, and a total of 21 stress gauges were installed. Three groups of second-order deep and shallow holes were constructed on the auxiliary side, and the depths of the stress gauges were 2 m and 3 m, respectively. A total of 6 stress gauges were installed, as shown in Fig. 21.

Figure 22 is the monitoring curve of the coal stress meter in the three areas of ABC before and after the drilling construction. The analysis shows that when the mechanical reaming pressure relief is carried out in the A and B areas, the stress level of the coal body is stable, and there is no stress fluctuation or sudden increase (the roof of the B area exploded on November 8, and some stress meters have a sharp rise and fall). During the pressure relief of the conventional large-diameter drilling in the C area, the 6 m stress meter in the coal wall showed a gradual upward trend, and the 8 m, 10 m, and 12 m stress meters all showed irregular sudden increases, with the highest increases of 3.8 MPa, 3.1 MPa, and 3.9 MPa, respectively, indicating that the conventional large-diameter drilling after pressure relief results in high stress in the peak area and a fast stress recovery speed. The pressure relief effect of reaming pressure relief on the concentrated static load area of the coal seam is obvious.

Support effect test

In order to evaluate the stress and deformation of the surrounding rock in various pressure relief zones, five newly constructed anchor cables, each measuring Φ21.8 × 4300 mm, were installed in the roof and on both sides of three designated areas (A, B, and C). The pre-tensioning force applied to each anchor cable was maintained at a minimum of 150 kN. After the installation of the anchor cable is complete, a dynamometer with a self-storage function is installed at the end of the anchor cable. This device is programmed to store data for a period exceeding two weeks, with a monitoring frequency set at every 10 min. Concurrently, the 'cross point method’ was employed to assess the deformation of the surrounding rock within the test area. A total of nine displacement monitoring stations were established along the roadway surface in the 3106-return airway. The displacements of the roadway’s sides, roof, and floor were recorded both prior to and following the construction of the pressure relief borehole. The configuration of the measurement points is illustrated in Fig. 23.

Figure 24a,b are the monitoring curves of the anchor cable stress gauges on the main side and the roof in the three regions, respectively. It can be seen from the diagram: (1) During the drilling construction phase, the average anchoring forces of the roof anchor cables in Areas A, B, and C were recorded at 74.1 kN, 86.4 kN, and 104.8 kN, respectively. Notably, the mechanical reaming area exhibited a significantly lower anchoring force compared to the conventional drilling anchor cables, with a maximum reduction of 29%. (2) Following the completion of the drilling construction, the stress levels of the roof anchor cables increased over a one-month period; however, the stress in the mechanical reaming area remained considerably lower than that observed in the conventional drilling area. This finding suggests that mechanical reaming effectively maintains a low-stress condition for the roof anchor cables over an extended duration, demonstrating its long-term efficacy. (3) During the drilling construction, the tensile force of the side anchor cables exhibited a gradual increase. The maximum abrupt change in tensile force within the mechanical reaming area was measured at 7.7 kN, which is 51.8% lower than the 16 kN observed in the conventional drilling area. This indicates that the tensile force of the side anchor cables in the mechanical reaming area is characterized by greater stability. (4) One month after the completion of drilling construction, the stress levels of the anchor cables in the mechanical reaming area continued to be significantly lower than those in the conventional drilling area, further supporting the conclusion that mechanical reaming is capable of maintaining a prolonged low-stress state for the anchor cables.

Figure 25a,b present the monitoring curves depicting the average displacements of the two sides, as well as the average displacements of the roof and floor, calculated as the mean values from three sets of measurement points within each region. The data illustrated in these figures indicate that during the drilling operations, there is an observable increase in the displacements of both the roof and the lateral sides of the roadway. Notably, the deformation observed on the lateral sides within the conventional drilling construction area is significantly greater, reaching a maximum of 51 mm/day. In contrast, the lateral displacements in the mechanical reaming pressure relief area can be reduced by as much as 63%, while the displacements of the roof and floor can be diminished by up to 51%. These findings suggest that the reaming pressure relief method exhibits a substantially superior control effect on the deformation of the surrounding rock in the roadway compared to the conventional large diameter drilling pressure relief approach.

Discussion

Compared with the traditional pressure relief method, the mechanical reaming pressure relief and anti-scour technology proposed in this paper shows certain advantages in pressure relief effect and protection of the supporting structure. However, limited by the test conditions (the geological structure of the test site, Menkeqing Coal Mine, is relatively simple, the buried depth of the coal seam is less than 700 m, and the test range is only 70 m), its large-scale promotion still needs to be systematically demonstrated in the dimensions of technical representativeness, applicability, and economy.

In terms of representativeness, the technology of mechanical reaming and pressure relief in hard coal is still in the theoretical improvement stage and undergoing pilot industrial testing. The thickness, strength, and stress conditions of coal seams vary across different mines. Therefore, the design of relevant parameters for mechanical reaming must be continuously explored and refined based on extensive large-scale testing in various mines, ultimately leading to broader implementation and application.

In terms of applicability, in order to promote the application of this technology under deep high-stress and complex geological conditions, it is necessary to further quantify the response law of the surrounding rock stress field under different reaming diameters and reaming points, and optimize the selection of key parameters. In addition, the reaming and pressure relief in the deep high-stress area may also trigger a higher energy event, causing construction safety risks. A lot of research is needed to clarify its application boundary.

In terms of economy, the construction efficiency of mechanical reaming is 50% lower than that of conventional drilling due to the increase in reaming construction links. According to rough calculations, the comprehensive cost of equipment, labor, and pulverized coal cleaning produced by mechanical reaming is 35% higher than that of conventional drilling. After its large-scale application, the drilling tool loss and equipment maintenance costs caused by hard coal reaming will continue to increase. The large-scale promotion of this technology needs to be further improved in terms of construction efficiency and pressure relief effect in order to reduce the comprehensive construction cost.

Conclusions

-

1.

The uniaxial compressive strength of the main coal seam in the Ordos area can reach up to 35 MPa, ranking first among the main rock burst mining areas in China. Under the condition of a hard coal seam, the pressure relief effect of the conventional drilling pressure relief method is poor, and it is easy to damage the basic support of the roadway in the process of pressure relief.

-

2.

Coal strength, borehole diameter, and lateral pressure coefficient are the main controlling factors affecting the effect of borehole pressure relief. The higher the uniaxial compressive and shear strength of the coal seam, the smaller the radius of the plastic zone of the borehole; thus, the pressure relief effect of the borehole in the hard coal seam is poor. After increasing the diameter of the borehole, the radius of the plastic zone increases, but when the diameter of the borehole increases to 300 mm, the increasing trend of the radius of the plastic zone weakens. Therefore, simply increasing the diameter of the borehole cannot improve the pressure relief effect of the borehole without limit.

-

3.

A new technology of mechanical reaming, pressure relief, and rockburst prevention in hard coal seams has been developed, which includes support, deep pressure relief, and unloading-support coupling. That is, the elastic energy accumulated in the coal body is released by the deep large hole, while the shallow small hole is used to ensure the bearing capacity of the support body, achieving a balance between pressure relief and support. The related technology has been applied in the Menkeqing Coal Mine in the Ordos area.

-

4.

Compared with the conventional drilling area, the amount of coal seam drilling powder in the mechanical reaming area is increased by 3.1 times, and the number per meter is increased by 70%. The pressure relief effect is obviously improved. Compared with the conventional drilling area, the anchoring force of the roof anchor cable in the mechanical reaming area is reduced by up to 29%, the mutation of the tension of the anchor cable on the side is reduced by up to 51.8%, the convergence of the two sides of the roadway is reduced by up to 63%, the convergence of the roof and floor is reduced by up to 51%, and the stress of the support body and the deformation of the surrounding rock are significantly reduced.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Pan, Y. S., Song, Y. M. & Liu, J. Pattern, change and new situation of coal mine rockburst prevention and control in China. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 42, 2081–2095. https://doi.org/10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2022.1048 (2023).

He, M. & Qi, W. Rock dynamics in deep mining. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 33, 1065–1082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2023.07.006 (2023).

Yu, M., Zuo, J., Sun, Y., Mi, C. & Li, Z. Investigation on fracture models and ground pressure distribution of thick hard rock strata including weak interlayer. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 32, 137–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2021.10.009 (2022).

Qi, Q. X. et al. Seventy years development of coal mine rockburst in China: Establishment and consideration of theory and technology system. Coal Sci. Technol. 47, 1–40. https://doi.org/10.13199/j.cnki.cst.2019.09.001 (2019).

Han, P., Zhang, C., Wang, X. & Wang, L. Study of mechanical characteristics and damage mechanism of sandstone under long-term immersion. Eng. Geol. 315, 107020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2023.107020 (2023).

Zhang, W., Wang, X., Xing, M. & Zhang, B. Theoretical and experimental study on the mechanical measurement of rock tensile fracture by ring radial compression. Géotechnique https://doi.org/10.1680/jgeot.24.01054 (2024).

Han, P., Wang, K., Pang, J., Ji, X. & Zhang, C. Response properties of geometries of coal penetrating fracture on seepage behavior. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 35, 191–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2025.01.003 (2025).

Zhang, S., Li, Y., Shen, B., Sun, X. & Gao, L. Effective evaluation of pressure relief drilling for reducing rockbursts and its application in underground coal mines. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 114, 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2018.12.010 (2019).

Wen, Y. L., Zhang, G. J. & Zhang, Z. Q. Numerical experiments of drilling pressure relief preventing roadway rockburst. Appl. Mech. Mater. 353–356, 1583–1587. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.353-356.1583 (2013).

Shi, Q., Mishra, B., Wang, S. & Xu, G. In situ assessment of the effectiveness of an undisturbed single driving entry’s relief borehole in coal burst-prone seam. Min. Metall. Explor. 38, 2443–2452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42461-021-00511-x (2021).

Zhu, S. T. et al. Research on mechanism of rockburst and large deformation coordination controlling in thick coal seam of deep shaft. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 34, 4262–4268. https://doi.org/10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2014.1542 (2015).

Pan, J. F. et al. Technical difficulties and emerging development directions of deep rockburst prevention in China. J. China Coal Soc. 49, 1291–1302. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2023.1480 (2024).

Pan, J. F. et al. Response law and limit of pressure relief drilling borehole in coal seams under incremental static loading. J. Min. Strata Control Eng. 7, 34–48. https://doi.org/10.13532/j.jmsce.cn10-1638/td.2024-1232 (2025).

Zhang, D. X. et al. Influence of coal seam thickness on pressure relief and energy release mechanism of large-diameter drilling hole. Coal Sci. Technol. 52, 40–50. https://doi.org/10.12438/cst.2023-0654 (2024).

Chen, M. et al. Experimental investigation on pressure relief mechanism of specimens with prefabricated reaming boreholes. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 56, 2949–2966. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-022-03159-1 (2023).

Yao, J. et al. Segmented enlarged-diameter borehole destressing mechanism and its influence on anchorage support system. Energy Sci. Eng. 8, 2831–2840. https://doi.org/10.1002/ese3.700 (2020).

Tan, Y. L., Guo, W. Y., Zhao, T. B. & Meng, X. J. Coal rib burst mechanism in deep roadway and “stress relief-support reinforcement” synergetic control and prevention. J. China Coal Soc. 45, 66–81. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.YG19.1772 (2020).

Gao, M. S., He, Y. L., Lu, C. P., Shao, X. & Yang, Z. Coordination mechanism of internal strong active support, soft structure pressure relief and anti-punching of roadway. J. China Coal Soc. 45, 2749–2759. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2020.0427 (2020).

Liu, G. L. et al. Mechanism and technology of rockburst prevention in deep coal tunnel based on controlling surrounding rock stress difference gradient. J. China Coal Soc. 49, 674–693. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2023.1769 (2024).

Wu, Y. Z. et al. Principle and technology of “pressure relief-support-protection” collaborative prevention and control in deep rockburst roadway. J. China Coal Soc. 46, 132–144. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.YG20.1821 (2021).

Xie, S. R. et al. Collaborative control technology of external anchor-internal unloading of surrounding rock in deep large-section coal roadway under strong mining influence. J. China Coal Soc. 47, 1946–1957. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.XR21.1990 (2022).

Savin, G. N. Stress Distribution Around Holes (NASA, 1970).

Kang, H. & Gao, F. Evolution of mining-induced stress and strata control in underground coal mines. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 43, 1–40. https://doi.org/10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2023.1055 (2024).

Zhang, W., Zhang, D., Guo, W. & Zhang, B. Experimental study on failure precursory characteristics and moisture content effect of pre-cracked rocks under graded cyclic loading and unloading. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 35, 249–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2024.12.014 (2025).

Funding

(Fund Project: Project supported and financed by the Shaanxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 2024JC-YBMS-261).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The research was conceptualized by Jia-hao Xie and Zi-wei Ding, who established the foundational framework for the study. Guang-an Zhu was responsible for designing the methodology, overseeing software development, and ensuring the integrity of data management. The validation of results, through the comparison of experimental and simulated data, was conducted by Jia-hao Xie and Xiao-qi Hao. Data analysis was performed by Jia-hao Xie, while Jin-dui Jia led the investigative efforts, which included conducting a literature review and collecting data. Resource management, encompassing equipment, technical support, and funding, was overseen by Zi-wei Ding. Jia-hao Xie ensured the accuracy and integrity of the data curated for the study. The original draft of the manuscript was authored by Jia-hao Xie, with subsequent review and editing conducted by Zi-wei Ding. Data visualization was managed by Jin-dui Jia. Guang-an Zhu provided supervision for the project, ensuring adherence to scientific standards, while Jia-hao Xie coordinated project workflow and communication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, Jh., Ding, Zw., Zhu, Ga. et al. Research and engineering practice on mechanical reaming for pressure relief and rock burst prevention technology in hard coal seam roadways. Sci Rep 15, 37368 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02002-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02002-1