Abstract

Mothers of children with burn injuries often experience psychological distress, affecting their well-being and children’s pain. This study evaluates the impact of resilience training on maternal resilience and child pain. This randomized clinical trial was conducted at Amir Al-Momenin Burn Hospital, Shiraz, Iran, with 50 mothers in 2021–2022. Participants were assigned to an intervention group (six-day resilience training) or a control group (standard care). Outcomes were measured at multiple time points using the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale and the Visual Analog Scale. Data were analyzed using SPSS v.22. The analysis revealed significant time effects on child pain intensity (B = − 0.84, p < 0.001) and maternal resilience (B = 3.99, p < 0.001). Significant group effects revealed greater improvements in the intervention group for child pain intensity (B = 2.85, p < 0.001) and maternal resilience (B = − 3.05, p < 0.001). The intervention group showed significant improvement in maternal resilience over time compared to the control group (B= − 2.06, p = 0.001), with no significant difference in child pain intensity over time compared to the control group (B = − 0.05, p = 0.69). Resilience training enhances maternal resilience and children’s pain over time. However, its impact on child pain intensity is limited compared to standard care. Therefore, integrating resilience training for mothers into pediatric burn care is recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Burn injuries represent a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in children1. It is estimated that 90% of these cases occur in low- and middle-income countries1. In Iran, the prevalence of burns among children is particularly high compared to other age groups, with approximately 3 million cases reported annually2.

Although burn injuries are common among children and their associated pain is severe, the management of burn pain remains insufficiently addressed3. Uncontrolled pain can have adverse effects on patients both in the short term and over the long term. It can induce anticipatory anxiety regarding future medical procedures, and heightened levels of pain and anxiety may impede wound re-epithelialization. This delay in healing can result in prolonged consequences affecting growth and mobility. Severe pain resulting from pediatric burns not only has significant psychological effects on the children but also exerts detrimental psychological impacts on their families4. Parents of children with burn injuries frequently experience feelings of guilt, blame, and shame5. They endure greater psychological distress compared to parents of children with other injuries or medical conditions6. While both mothers and fathers are profoundly impacted by their child’s burn injury7, mothers typically experience greater psychological distress compared to fathers8,9.

A substantial body of research indicates a high prevalence of psychological distress among mothers of burn-injured children. Studies consistently report elevated rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression in these mothers10,11,12,13. Maternal psychological stress following pediatric burn injuries is associated with a range of adverse child outcomes. Children whose mothers experience significant stress may exhibit more emotional regulation difficulties, struggling to manage their emotions effectively12,13,14. In addition, maternal stress, in particular, has been identified as a critical factor that can exacerbate a child’s pain experience15. In line with this, studies show the positive effect of mothers’ psychological well-being on their children’s chronic pain16,17. In the field of pediatric burn injury, only one study by Brown et al. (2019) has shown that increased psychological support for parents may reduce procedural pain-related distress in young burn-injured children18. In this regard, providing the strategies to enhance maternal resilience seems crucial to alleviate the psychological burden on mothers and improve the mental and physical well-being of their children.

Resilience is characterized by adaptive and dynamic changes in cognitive, emotional, and behavioral domains that contribute to enhanced mental health19. Parents of children who survive burn injuries often undergo substantial psychological distress and exhibit low resilience20. Promoting resilience in mothers can buffer the negative effects of stress, leading to improved coping mechanisms and better outcomes for both the mother and the child21. Therefore, resilience training may be a beneficial strategy to enhance the resilience of mothers of children with burn injuries and reduce their children’s pain.

Resilience training is a structured psychological intervention designed to enhance adaptive coping and emotional regulation, enabling individuals to manage stress more effectively22,23,24. While there is a paucity of research specifically on resilience training for mothers of burn-injured children, the broader literature on resilience and stress management provides valuable insights21. In the context of burn injuries, it was shown that psychotherapy, including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and other evidence-based approaches, can help mothers develop coping skills and manage their psychological distress13,25. In other contexts, research has shown that such training can significantly reduce psychological distress in mothers of children with chronic conditions, improving their emotional well-being and caregiving capacity26,27,28,29. However, no experimental studies have been found that assess the impact of resilience training for mothers on the pain experience of children with burn injuries. In this line, Brown et al. (2019) proposed a conceptual model within the pediatric burn unit framework, suggesting that variations in parental procedural behavior mediate the relationship between parental psychological distress and child procedural distress30. This model implies that enhancing acute psychological support for parents of burn-injured children can alleviate procedural pain-related distress in these young patients30. Given the well-established link between maternal stress and child health outcomes, reducing maternal distress may contribute to better pain management in children by fostering a more supportive and responsive caregiving environment26. However, there is a need for studies specifically assessing the impact of resilience training on both maternal resilience and the pain experience of children with burn injuries.

Given the high risk of psychological distress among mothers of children with burn injuries31,32 and its potential impact on their children’s pain33,34, it is crucial to assess effective psychological interventions. While existing studies underscore the benefits of parental resilience training35 and its potential to improve child pain outcomes16,17,36,37, most focus on chronic pain conditions other than burns. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the impact of resilience training for mothers of hospitalized children with burn injuries on the resilience of mothers and the pain experienced by their burn-injured children, guided by the conceptual model established by Brown et al. (2019). We hypothesize that resilience training for these mothers will lead to significant improvements in maternal resilience and reductions in child pain, as assessed during and after the intervention and at follow-up points.

Method

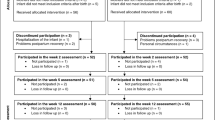

This study was conducted in accordance with the CONSORT guidelines38,39 [see the CONSORT diagram in Fig. 1].

Study design

This study is designed as a parallel-group, double-blind, randomized clinical trial with comparator controls.

Participants and settings

The study was conducted between November 2021 and April 2022 at the pediatric ward of Amir Al-Momenin Burn Hospital, affiliated with Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, in Shiraz, Iran. The participants consisted of 50 mothers of children aged 6 to 12 years who were hospitalized with burn injuries (degree 2 or greater) and their respective children. Inclusion criteria required that the children have a burn injury diagnosed by the treating physician, maternal literacy, and the willingness of both mothers and children to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria included chronic physical or mental illnesses in the mother or child, maternal absence from more than two resilience training sessions, pre-existing child pain before the burn injury, and severe fractures or non-burn-related wounds in the child.

Mothers of hospitalized children who met the inclusion criteria were approached by the principal researcher, and written informed consent was obtained from those willing to participate. After eligibility was confirmed, participants were randomly assigned to either the experimental group (n = 25) or the control group (n = 25) using a 1:1 random sampling method. The experimental group received the resilience training intervention, while the control group did not. Both groups completed a resilience questionnaire at three time points: before the first session, before the fourth session, and immediately after the final session. Additionally, participants completed the questionnaire daily until the fifteenth day of hospitalization, totaling 12 assessments at 5 p.m.

Sample size calculation

Sample size was estimated using G*Power 3.1 software. Based on an α level of 0.05, a power of 0.90, and an effect size of 0.40 40, the required sample size was 47. To compensate for a 20% anticipated dropout rate, 56 participants were recruited, and 50 completed the study.

Randomization and blinding

To minimize bias and enhance the reliability of the findings, randomization and blinding were rigorously applied in this study. Children with burn injuries and their mothers were randomly assigned to either the intervention group, which received resilience training for the mothers, or the control group, which did not receive any resilience training. Randomization was performed using the randomizer.org tool, with participants randomly allocated to either the intervention or control group. This method of simple randomization was conducted by an independent researcher who was not involved in participant recruitment, intervention delivery, or outcome assessment. Each child and their corresponding mother were assigned a unique identification number. These numbers were entered into the randomization software, which then randomly allocated the participants into either the intervention or control group using these identifiers. The use of random allocation was crucial to eliminate selection bias and ensure that each participant had an equal chance of being assigned to either the intervention or control group, thereby enhancing the internal validity of the study.

To prevent data contamination, data collection from the control group was completed before data collection from the intervention group. This sequencing ensured that the control group’s data remained unaffected by the subsequent intervention and maintained the integrity of the data across both groups.

Blinding was rigorously implemented in this study to reduce the potential for bias. Participants were blinded to their group assignments, meaning they were unaware of whether they were part of the intervention or control group. This was critical to prevent any influence on their behavior, expectations, or responses that could arise from knowing their assigned group. Moreover, the intervention and control groups were designed to be indistinguishable to the participants, which further minimized the likelihood of bias related to their perception of the intervention. In addition, the outcome assessors and data analysts were also blinded to the group allocations. These individuals were responsible for collecting and interpreting the outcome data, and their lack of knowledge regarding the participants’ group assignments ensured that their assessments and analyses were not influenced by any preconceived expectations. By ensuring that both the participants and the evaluators remained blinded throughout the study, we were able to mitigate the risk of performance bias and detection bias, both of which are essential for maintaining the internal validity of the study. These measures were taken to minimize bias and ensure the reliability and validity of the study results41.

Resilience intervention condition

After completing the data collection for the control group, mothers in the intervention group participated in a six-session resilience training program. The sessions focused on stress management (2 sessions), identifying and addressing cognitive distortions (2 sessions), and applying positive psychology techniques (2 sessions). These sessions were conducted in groups of 3–6 participants at the Amir Al-Momenin Burn Hospital’s conference hall, with each session lasting 60–90 min. The sessions were held daily over a six-day period. The program was led by a psychiatric nurse (the third author), who holds specialized training in mental health nursing and has received additional training in resilience-building techniques and therapeutic interventions for individuals facing psychological distress.

The first session served as a needs assessment to tailor the program to the participants’ specific requirements. Various instructional methods were used, including visual aids (charts, films, PowerPoint slides), interactive group discussions, and practical exercises. Each session began with a lecture by the nurse, followed by group discussions and exercises. Participants were encouraged to select the techniques most beneficial for them and integrate them into their daily routines, rather than attempting to practice all techniques at once. Feedback on the strategies’ effectiveness was solicited throughout the program. Table 1 outlines the objectives and content covered in each of the six training sessions.

Control condition

Mothers in the control group received standard care and did not participate in the resilience training. Upon completion of the follow-up assessments, they were provided with educational materials on resilience skills at the hospital.

Measures

Data were collected using online questionnaires and forms. A socio-demographic and clinical assessment form, developed by the researchers, was utilized to gather information on the socio-demographic characteristics of the mothers of children with burn injuries (including age, occupation, educational level, and economic status) and the clinical-demographic details of their children (including age, gender, percentage of burns, degree of burns, cause of burns, hospitalization duration, and postoperative day). The outcome measures were as follows:

Primary clinical outcome

Resilience was designated as the primary clinical outcome, based on the assumption that enhanced parental resilience may serve as a protective factor against child pain outcomes36. Resilience was assessed using the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC)47.

The CD-RISC consists of 25 items, each rated on a Likert scale from 0 (not true at all) to 4 (very true, nearly all the time). The total score can range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater resilience. The scale demonstrates strong internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.8947. The scale has demonstrated good convergent validity. Factor analysis revealed five distinct factors within the scale47. The Persian version of the CD-RISC also exhibits high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89) and sufficient validity48,49. In this study, the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale showed high reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82.

Secondary clinical outcome

The researchers used the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for pain assessment, which consists of a 10-centimeter-long vertical or horizontal line, with 0 indicating the absence of pain and 10 representing extreme or intolerable pain. The scale has demonstrated concurrent validity with the Numerical Pain Rating Scale (NPRS), ranging from 0.71 to 0.78, and test-retest reliability ranging from 0.71 to 0.9950. In Iran, the scale’s reliability has been reported to be 0.8151. In the present study, the reliability of the tool was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, yielding a coefficient of 0.87.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS software, version 22 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, were used to summarize the data. The normality of data distribution was first assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to verify adherence to the normality assumption. To evaluate group homogeneity regarding demographic and clinical characteristics, the chi-square test (or Fisher’s exact test when appropriate) was applied for categorical variables, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for continuous variables due to the non-normal distribution of the data. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was utilized for assessing significant differences within groups, while the Mann-Whitney U test was employed to compare differences between groups. Missing data were addressed using the mean series imputation method in SPSS. For the purposes of data analysis and interpretation, the treatment groups were coded as intervention (0) and control (1).

In this study, a Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) model was employed to assess the impact of the intervention on the improvement of children’s pain and mothers’ resilience. Given that the data on the effect of resilience training were collected over twelve consecutive measurements, the responses were both correlated and longitudinal. The GEE method is particularly suited for analyzing such correlated and longitudinal data. This method evaluated the effect of the intervention (resilience training) and calculated the variance matrix using the exchangeable correlation structure in the longitudinal context. The GEE technique is valuable for handling repeated measures or time-series data and for estimating causal models across panels or for entire datasets. It provides asymptotic estimates based on quasi-likelihoods, even when correlations between explanatory and dependent variables are unknown or when there are missing partial correlations52. Statistical significance was defined as a P-value of less than 0.05.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, with reference number IR.SUMS.REC.1398.1098. It was also registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (Registration number: IRCT20201001048893N2, 8/12/2020, https://irct.behdasht.gov.ir/search/result?query=IRCT20201001048893N2). The study was conducted in adherence to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and all participants provided written consent after being informed about the study procedures. The research methods were performed in accordance with the applicable guidelines and regulations. Prior to participation, eligible mothers of children with burn injuries were provided with detailed information about the study. Consent was obtained from both the mothers and, where applicable, the children. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without facing any negative repercussions. To avoid any financial burden on the participants, their involvement in the study was at no cost. Confidentiality was strictly maintained; data were anonymized, and questionnaires were assigned numerical codes instead of using personal identifiers. Upon completion of the study, educational pamphlets on resilience skills were provided to the control group as a form of post-study support.

Results

Of the 65 participants (children with burn injuries and their mothers) assessed for eligibility, 56 were found to meet the criteria. Six mothers had to be excluded from the study—three from each of the intervention and control groups—because their children were discharged before completing the training sessions. Consequently, 50 participants completed the study, with 25 in the control group and 25 in the intervention group.

The mean age of the mothers was 33.80 years (standard deviation [SD] = 8.47), while the mean age of their children was 9.64 years (SD = 3.29). Most mothers had a high school education (82%). 70% resided in rural areas, and 92% were unemployed (Table 2). Among the children, 52% were male, 54% had upper extremity burns, and 74% had second- or third-degree burns. Additionally, 44% of the children were admitted with burns covering more than 20% of their bodies. There were no significant differences in baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics between the intervention and control groups (p > 0.05).

The baseline characteristics of the participants are detailed in Tables 2 and 3. Most of the demographic and clinical characteristics did not show significant differences between the intervention and control groups, indicating a relative homogeneity among the study participants. However, a significant difference was observed in fathers’ education level (p = 0.017), which could be considered a potential influencing factor in interpreting the study findings.

The results of the GEE analysis revealed significant main effects of time on child pain intensity (B = − 0.84, p < 0.001) and maternal resilience (B = 3.99, p < 0.001), indicating that both child pain intensity and maternal resilience significantly improved over time. These findings suggest that, regardless of group membership, the passage of time had a substantial effect on both outcomes, with mothers showing increased resilience and children experiencing reduced pain intensity over the course of the study.

Moreover, the analysis revealed significant main effects of group on child pain intensity (B = 2.85, p < 0.001) and maternal resilience (B = − 3.05, p < 0.001). These results indicate that the intervention group demonstrated significantly greater improvements in both child pain intensity and maternal resilience compared to the control group. Specifically, when controlling for the effect of time, the intervention group exhibited a more pronounced reduction in child pain intensity and a greater increase in maternal resilience than the control group. These findings suggest that the intervention had a beneficial impact on both outcomes, beyond the natural changes that occurred over time.

The interaction between group and time for maternal resilience was statistically significant, indicating that the GEE analysis revealed a significant difference in maternal resilience between the intervention and control groups over time (B = − 2.06, p = 0.001). Specifically, this interaction suggests that the intervention group showed a greater improvement in maternal resilience over time compared to the control group. This finding highlights the effectiveness of the intervention in enhancing maternal resilience, with the benefits becoming more pronounced as time progressed.

In contrast, the interaction between group and time for child pain intensity was not statistically significant (B = − 0.05, p = 0.69), suggesting that the improvement in child pain intensity over time did not differ significantly between the intervention and control groups. This lack of a significant interaction indicates that while pain intensity decreased for both groups over time, the intervention did not produce a significantly greater reduction in pain intensity compared to the control group. Additional details are provided in Table 4; Figs. 2 and 3.

Paired t-test analysis was conducted to compare participants’ scores between the first day’s assessment and subsequent assessments. For the control group, the analysis of mothers’ resilience scores revealed significant differences between the mean resilience score on the first day and the scores on the 11th day (t = − 4.01, df = 10, p = 0.002), the 13th day (t = − 5.29, df = 4, p = 0.003), and the 15th day (t = − 5.89, df = 10, p = 0.03). There was a significant reduction in pain intensity from the first day’s assessment to all subsequent pain assessments in children of both the control and experimental groups (p < 0.05). Additionally, a significant increase in resilience was observed in the experimental group between the first day’s assessment and all subsequent resilience assessments (p < 0.05).

While both groups showed improvements over time, the intervention group showed more pronounced and sustained improvements. This suggests that the resilience training program was an effective addition to the standard care regimen, emphasizing the importance of caregiver emotional support in pediatric pain management. These findings underscore the importance of integrating resilience-focused psychological support into routine burn care to optimize both maternal and child outcomes. They highlight the need for holistic, family-centered approaches in pediatric burn care settings to enhance coping mechanisms and overall recovery.

Discussion

Given the high risk of psychological distress among mothers of children with burn injuries31,32 and its potential impact on their children’s pain33,34, it is crucial to assess effective psychological interventions. Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the effect of a resilience training intervention for mothers of hospitalized children with burn injuries on the resilience of mothers and the pain of their burnt children.

The results demonstrated that the intervention significantly improved maternal resilience, with sustained benefits observed throughout the study. Previous studies have shown that resilience training can enhance mental health in mothers facing various challenges, including intellectual disabilities53, leukemia54, and ADHD55. While studies directly investigating resilience training for mothers of children with burn injuries are limited, some research on psychosocial interventions for these parents suggests promising results. For example, Sveen et al. (2017) found that a six-week psychoeducational program reduced post-traumatic stress in parents of burned children25. Similarly, Shaygan et al. (2025) reported that resilience programs alleviated anxiety in mothers during the acute phase of hospitalization56, while Tully et al. (2022) associated improved resilience with reduced traumatic stress several months post-injury57. Furthermore, Hornsby et al. (2019) conducted a systematic review of psychosocial interventions, emphasizing the importance of early psychosocial support in promoting the psychological recovery of parents following their children’s burn injuries. According to this review, parent group counseling, a form of resilience training, has shown promise in enhancing maternal resilience58.

Dealing with a child’s burn injury is one of the most stressful experiences for parents57, especially mothers14,59, leading to elevated stress, anxiety, depression, and other emotional burdens59. These psychological reactions can negatively affect both the parents’ and children’s well-being. Previous research suggests that parental distress can increase the risk of low resilience in children60, while low resilience in pediatric burn survivors is linked to more intense symptoms in caregivers61. In this study, it seems that resilience training helped mothers to manage psychological stress, improve coping strategies, and enhance mental health support, benefiting both the mothers and their children. This study suggests that resilience training improved mothers’ psychological well-being and likely led to better outcomes for their children by alleviating parental distress, which in turn enhanced maternal resilience. While improvements in the child’s condition due to medical treatment may have contributed to the outcomes, resilience training seems to have had a positive effect on both mothers and children. Therefore, incorporating a family-based resilience approach in burn services is recommended to support both parents and children following trauma.

The resilience training group showed a significant reduction in child pain compared to its baseline. Furthermore, it exhibited a greater reduction compared to the control group, considering the main effect of the group. These findings suggest that enhancing maternal resilience may improve coping strategies and enhance children’s pain management. This highlights the broader benefits of resilience training beyond individual coping mechanisms. Previous studies indicate that parental behaviors significantly affect children’s pain during medical procedures62,63,64,65. For example, Brown et al. (2019) found that parental psychological distress impacts children’s pain during burn care, and acute psychological support for parents may reduce pain-related distress in children30. Additionally, Maia Brasil et al. (2012) emphasized the role of family resilience and emotional support in reducing children’s pain post-burn injury66. Psychoeducation for parents not only reduces their stress but also strengthens family cohesion and aids the child’s recovery67. Although the impact of resilience training on children’s pain had not been fully explored, this study addresses this gap by demonstrating its positive effects.

In the control group, where mothers did not receive resilience training, a reduction in children’s pain was observed, though less pronounced than in the intervention group. Both groups received standard care, including pharmacological treatments, which are critical in managing pediatric burn pain68,69. However, pain reduction in the control group could also be attributed to the natural healing process70, tissue regeneration70, and parental presence during procedures71. Repeated exposure to painful procedures, such as dressing changes, can reduce both emotional and physiological pain responses over time72. While these factors contributed to pain relief in the control group, resilience training for mothers led to more significant improvements in pain management. Effective pain management is essential, as untreated pain can delay wound healing73,74 and lead to chronic pain or post-traumatic stress75,76. Pharmacological interventions remain the cornerstone of effective pediatric burn pain management68,69. However, pharmacological treatments can have limitations, including insufficient pain control, respiratory depression, and excessive sedation77. Additionally, children often respond less effectively to medical treatments compared to adults, highlighting the importance of complementary or alternative therapies78. Non-pharmacological pain management strategies, such as resilience training for mothers, offer an effective, cost-efficient, and practical approach, reducing reliance on painkillers while enhancing children’s pain relief.

Our study supports Brown et al. (2019), showing that enhancing psychological support for parents of burn-injured children alleviates procedural pain-related distress in these children. Resilience training for mothers in the experimental group reduced their psychological distress, which in turn decreased their children’s pain. While the control group also showed pain reduction, adding resilience training to standard care was more effective. This effect may be due to improved parental coping, which creates a more supportive environment that reduces anxiety and enhances pain management. Resilient parents can also model adaptive coping behaviors, influencing their children’s pain perception and tolerance. This study highlights the importance of integrating resilience training for parents in pediatric burn care.

A key limitation of this study was the high attrition rate due to child discharges, which may have influenced the results. Additionally, cultural and economic factors, which could affect coping mechanisms, were not considered and may have impacted the outcomes of resilience training and pain management. Future research should address these variables to better understand their influence. The use of mean imputation for missing data may have underestimated variability, so more robust methods like multiple imputation or maximum likelihood estimation are recommended. The sample was predominantly from rural areas with limited resources, and many children had upper extremity burn injuries, limiting generalizability. The small sample size also affects the robustness of the conclusions. Future studies should include larger, more diverse populations. Furthermore, the study did not isolate the effects of pharmacological treatments, which should be analyzed in future research to better evaluate their role in pain reduction. Finally, exploring other psychosocial interventions and their impact on maternal resilience and child outcomes would be valuable.

Conclusion

Parental psychological distress following a child’s burn injury can impact both the child’s physical recovery and the ongoing psychological well-being of both the child and the mother79. Therefore, implementing effective psychological interventions for mothers is crucial. In the present study, resilience training for mothers led to a significantly greater improvement in maternal resilience over time compared to the control group. However, although pain intensity decreased significantly in both groups, the reduction in the intervention group was greater but not statistically significant compared to the control group over time. The training likely improves maternal coping strategies and mental health support, which fosters a more supportive environment for the child. This, in turn, may reduce the child’s anxiety and pain perception.

The study supports integrating resilience training into family-centered pediatric burn care, offering mothers essential psychological support to manage distress and adapt to their child’s condition. This approach is accessible, cost-effective, and suitable for rehabilitation. However, further research is needed to better address the psychosocial needs of these families, with a focus on tailoring interventions based on individual circumstances and burn injury characteristics.

Data availability

Upon a reasonable request from scientists, the associated data can be made available by reaching out to the corresponding author via email. Moreover, researchers interested in obtaining the intervention manual may contact the corresponding author for further information.

References

Abedin, M., Rahman, F. N., Rakhshanda, S. & Mashreky, S. R. Epidemiology of non-fatal burn injuries in children: evidence from Bangladesh health and injury survey 2016. 6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjpo-2022-001412 (2022).

Dehghani, M., Hakimi, H., Mosazadeh, S., Zeinali, Z. & Shafiepour, S. Z. Survey related factors to burning of 1–6 years old children referred to Velayat’s health and training center of burn in Rasht City. Pajouhan Sci. J. 16, 1–10 (2018).

Carpinelli, L., D’Elia, D. & Savarese, G. The multilevel pathway in MSTs for the evaluation and treatment of parents and minor victims of aces: Qualitative analysis of the intervention protocol. 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9030358 (2022).

Storey, K., Kimble, R. M. & Holbert, M. D. The management of burn pain in a pediatric burns-specialist hospital. Paediatr. Drugs. 23, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40272-020-00434-y (2021).

Bayuo, J. & Wong, F. K. Y. Issues and concerns of family members of burn patients: a scoping review. Burns: J. Int. Soc. Burn Injuries 47, 503–524 (2021).

Kent, L., King, H. & Cochrane, R. Maternal and child psychological sequelae in paediatric burn injuries. Burns 26, 317–322 (2000).

Townsend, A. N. et al. Parent traumatic stress after minor pediatric burn injury. J. Burn Care Research: Off. Publ. Am. Burn Assoc. 44, 329–334. https://doi.org/10.1093/jbcr/irac055 (2023).

Egberts, M. R., Van de Schoot, R., Geenen, R. & Van Loey, N. E. Parents’ posttraumatic stress after burns in their school-aged child: A prospective study. Health Psychol. 36, 419 (2017).

Sveen, J. & Willebrand, M. Feelings of guilt and embitterment in parents of children with burns and its associations with depression. Burns 44, 1135–1140 (2018).

Egberts, M. R. et al. Mothers’ emotions after pediatric burn injury: Longitudinal associations with posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms 18 months postburn. J. Affect. Disord. 263, 463–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.140 (2020).

Sveen, J. et al. Internet-based information and self-help program for parents of children with burns: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Internet Interv. 2, 367–371 (2015).

Yako, J. P. W. Exploring paediatric Burns: narrative accounts from caregivers in Khayelitsha. (Cape Town, 2005).

Bakker, A. Beyond Pediatric Burns: a Family Perspective on the Psychological Consequences of Burns in Children (Utrecht University, 2013).

Haag, A. C. & Landolt, M. A. Young children’s acute stress after a burn injury: Disentangling the role of injury severity and parental acute stress. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 42, 861–870 (2017).

Matsuda-Castro, A. C. & Linhares, M. B. M. Pain and distress in inpatient children according to child and mother perceptions. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto) 24, 351–359 (2014).

Khu, M., Soltani, S., Neville, A., Schulte, F. & Noel, M. Posttraumatic stress and resilience in parents of youth with chronic pain. Children’s Health Care 48, 142–163 (2019).

Beeckman, M., Simons, L. E., Hughes, S., Loeys, T. & Goubert, L. Investigating how parental instructions and protective responses mediate the relationship between parental psychological flexibility and pain-related behavior in adolescents with chronic pain: A daily diary study. Front. Psychol. 10, 2350 (2019).

Brown, E. A., De Young, A., Kimble, R. & Kenardy, J. Impact of parental acute psychological distress on young child pain-related behavior through differences in parenting behavior during pediatric burn wound care. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings. 26, 516–529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-018-9596-1 (2019).

Kalisch, R. et al. Deconstructing and reconstructing resilience: a dynamic network approach. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 14, 765–777 (2019).

McGarry, S. et al. Paediatric medical trauma: the impact on parents of burn survivors. Burns 39, 1114–1121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2013.01.009 (2013).

Wu, G. et al. Understanding resilience. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 7, 10 (2013).

Chmitorz, A. et al. Intervention studies to foster resilience—a systematic review and proposal for a resilience framework in future intervention studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 59, 78–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.11.002 (2018).

Forbes, S. & Fikretoglu, D. Building resilience: the conceptual basis and research evidence for resilience training programs. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 22, 452–468. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000152 (2018).

Denckla, C. et al. Psychological resilience: An update on definitions, a critical appraisal, and research recommendations. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 11 https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1822064 (2020).

Sveen, J., Andersson, G., Buhrman, B., Sjöberg, F. & Willebrand, M. Internet-based information and support program for parents of children with Burns: A randomized controlled trial. Burns 43, 583–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2016.08.039 (2017).

Kaboudi, M., Abbasi, P., Heidarisharaf, P., Dehghan, F. & Ziapour, A. The effect of resilience training on the condition of style of coping and parental stress in mothers of children with leukemia. Int. J. Pediatr. 6, 7299–7310. https://doi.org/10.22038/IJP.2018.29245.2559 (2018).

Saba, S., Arsalani, N., Hosseini, M. A., Soltani, P. & Azizi, M. The effect of resilience training on the stress of mothers of students with down syndrome. Iran. Rehabil. J. https://doi.org/10.32598/irj.21.3.1906.1 (2023).

Luo, Y. & Xia, W. Effectiveness of a mobile Device-Based resilience training program in reducing depressive symptoms and enhancing resilience and quality of life in parents of children with cancer: Randomized controlled trial. 23, e27639 (2021). https://doi.org/10.2196/27639

Naderpour, M. et al. The effect of resiliency training on mental health and resilience of pregnant women with unwanted pregnancy: A randomized clinical trial. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 29, 231–237. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijnmr.ijnmr_389_21 (2024).

Brown, E. A., De Young, A., Kimble, R. & Kenardy, J. Impact of parental acute psychological distress on young child pain-related behavior through differences in parenting behavior during pediatric burn wound care. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings. 26, 516–529 (2019).

Egberts, M. R., van de Schoot, R., Geenen, R. & Van Loey, N. E. E. Mother, father and child traumatic stress reactions after paediatric burn: Within-family co-occurrence and parent-child discrepancies in appraisals of child stress. Burns 44, 861–869 (2018).

Egberts, M. R. et al. Mothers’ emotions after pediatric burn injury: Longitudinal associations with posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms 18 months postburn. J. Affect. Disord. 263, 463–471 (2020).

France, E. et al. A meta-ethnography of how children and young people with chronic non‐cancer pain and their families experience and understand their condition, pain services, and treatments. Cochrane Database Syst. Reviews (2023).

Sil, S., Woodward, K. E., Johnson, Y. L., Dampier, C. & Cohen, L. L. Parental psychosocial distress in pediatric sickle cell disease and chronic pain. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 46, 557–569 (2021).

Aivalioti, I. & Pezirkianidis, C. The role of family resilience on parental well-being and resilience levels. Psychology 11, 1705–1728 (2020).

Cox, D., McParland, J. L. & Jordan, A. Parenting an adolescent with complex regional pain syndrome: A dyadic qualitative investigation of resilience. Br. J. Health. Psychol. 27, 194–214 (2022).

Hanania, J. W. Protective Parental Influences in Pediatric Chronic Pain (Northeastern University, 2021).

Campbell, M. K., Elbourne, D. R. & Altman, D. G. CONSORT statement: Extension to cluster randomised trials. Bmj 328, 702–708 (2004).

Montgomery, P. et al. Reporting randomised trials of social and psychological interventions: the CONSORT-SPI 2018 extension. Trials 19, 1–14 (2018).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G. & Buchner, A. G* power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 39, 175–191 (2007).

Cook, T. D., Campbell, D. T. & Shadish, W. Experimental and quasi-experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference (Houghton Mifflin Boston, 2002).

Beck, J. S. & Beck, A.Cognitive behavior therapy. (Basics Beyond Guilford Publication, New York, 2011).

Kabat-Zinn, J. & Hanh, T. N. Full Catastrophe Living (Revised Edition): Using the Wisdom of your Body and Mind To Face Stress, Pain, and Illness (Random House Publishing Group, 2013).

Stahl, B. & Goldstein, E. A mindfulness-based Stress Reduction Workbook (New Harbinger Publications, 2019).

Villani, D. Integrating Technology in Positive Psychology Practice (Igi global, 2016).

Seligman, M. E. Positive psychology: A personal history. Ann. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 15, 1–23 (2019).

Connor, K. M. & Davidson, J. R. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD‐RISC). Depress. Anxiety 18, 76–82 (2003).

Abdi, F., Sh, B., Ahadi, H. & Sh, K. Psychometric properties of the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC) among women with breast cancer. J. Res. Psychol. Health 13, 81–99 (2019).

Derakhshanrad, S. A., Piven, E., Rassafiani, M. & Hosseini, S. A. Standardization of Connor-Davidson resilience scale in Iranian subjects with cerebrovascular accident. J. Rehabil. Sci. Res. 1, 73–77. https://doi.org/10.30476/jrsr.2014.41059 (2014).

Kahl, C. & Cleland, J. A. Visual analogue scale, numeric pain rating scale and the McGill pain questionnaire: An overview of psychometric properties. Phys. Therapy Rev. 10, 123–128 (2005).

Dehghan, M., Ahmadi, A. & Jalili, S. A study of pain and anxiety/depression severity on patients with nonspecific chronic low back pain. J. Shahrekord Univ. Med. Sci. 20 (2018).

Park, H. W. & Park, S. H. Association between coronavirus disease 2019-related workplace interventions and prevalence of depression and anxiety. Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 34, e11. https://doi.org/10.35371/aoem.2022.34.e11 (2022)

Hosseini Ghomi, T. & Jahanbakhshi, Z. Effectiveness of resilience training on stress and mental health of mothers whose have children suffering mental retardation. Couns. Cult. Psycotherapy 12, 205–228. https://doi.org/10.22054/qccpc.2020.50262.2327 (2021).

Kaboudi, M., Abbasi, P., Heidarisharaf, P., Dehghan, F. & Ziapour, A. The effect of resilience training on the condition of style of coping and parental stress in mothers of children with leukemia. Int. J. Pediatr. 6, 7299–7310 (2018).

Tabatabaei, S. M. & Chalabainloo, G. The effectiveness of resilience training on positive and negative affect and reduction of psychological distress in mothers of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. HBI J. 23, 438–449. https://doi.org/10.32598/jams.23.4.1224.5 (2020).

Shaygan, M., Dehghan Manshadi, Z., Hosseini, F. A. & Shaygan, M. Building resilience: A promising approach to reduce anxiety in mothers and hospitalized children with burn injuries. Burns: J. Int. Soc. Burn Injuries 51, 107374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2025.107374 (2025).

Tully, C. B., Amatya, K., Batra, N., Inverso, H. & Burd, R. S. Parent resilience after young child minor burn injury. Families, Systems, & Health. https://doi.org/10.1037/fsh0000703 (2022).

Hornsby, N., Blom, L. & Sengoelge, M. Psychosocial interventions targeting recovery in child and adolescent Burns: A systematic review. J. Pediatr. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsz087 (2019).

Heath, J. Peer-informed Support for Parents of burn-injured Children (University of the West of England, 2020).

Quezada Berumen, L., González-Ramírez, M. & Mecott, G. Explanatory model of resilience in pediatric burn survivors. J. Burn Care Res.: Off. Publ. Am. Burn Assoc. 37 https://doi.org/10.1097/BCR.0000000000000261 (2015).

Isokääntä, S., Koivula, K., Honkalampi, K. & Kokki, H. Resilience in children and their parents enduring pediatric medical traumatic stress. Pediatr. Anesth. 29, 218–225 (2019).

Chorney, J. M. et al. Healthcare provider and parent behavior and children’s coping and distress at anesthesia induction. J. Am. Soc. Anesthesiol. 111, 1290–1296 (2009).

Chambers, C. T., Craig, K. D. & Bennett, S. M. The impact of maternal behavior on children’s pain experiences: An experimental analysis. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 27, 293–301 (2002).

Cohen, L. L., Manimala, R. & Blount, R. L. Easier said than done: what parents say they do and what they do during children’s immunizations. Children’s Health Care 29, 79–86 (2000).

McGrath, P. J. & Frager, G. Psychological barriers to optimal pain management in infants and children. Clin. J. Pain 12, 135–141 (1996).

Gonçalves, M., Brasil, E. & De Brito, M. M. E. & Neyva Da Costa Pinheiro, P. Characterization of families of children admitted in a burning treatment center. J. Nurs. UFPE/Revista De Enfermagem UFPE 6 (2012).

Cioga, E., Cruz, D. & Laranjeira, C. Parental adjustment to a burn-injured child: how to support their needs in the aftermath of the injury. Front. Psychol. 15, 1456671 (2024).

Gandhi, M., Thomson, C., Lord, D. & Enoch, S. Management of pain in children with burns. Int. J. Pediatrics 825657 (2010).

Shiferaw, A., Mola, S., Gashaw, A. & Sintayehu, A. Evidence-based practical guideline for procedural pain management and sedation for burn pediatrics patients undergoing wound care procedures. Annals Med. Surg. 83, 104756 (2022).

Brown, N. J. The impact of a child’s pain, anxiety and stress on burn re-epithelialisation (2014).

Azak, M., Aksucu, G. & Çağlar, S. The effect of parental presence on pain levels of children during invasive procedures: A systematic review. Pain Manage. Nursing: Official J. Am. Soc. Pain Manag. Nurses. 23, 682–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2022.03.011 (2022).

Chester, S. J. et al. Effectiveness of medical hypnosis for pain reduction and faster wound healing in pediatric acute burn injury: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 17, 1–11 (2016).

Brown, N. J., Kimble, R. M., Rodger, S., Ware, R. S. & Cuttle, L. Play and heal: randomized controlled trial of ditto™ intervention efficacy on improving re-epithelialization in pediatric burns. Burns 40, 204–213 (2014).

Brown, N. J., Kimble, R. M., Gramotnev, G., Rodger, S. & Cuttle, L. Predictors of re-epithelialization in pediatric burn. Burns 40, 751–758 (2014).

Dauber, A., Osgood, P. F., Breslau, A. J., Vernon, H. L. & Carr, D. B. Chronic persistent pain after severe Burns: a survey of 358 burn survivors. Pain Med. 3, 6–17 (2002).

De Young, A. C., Kenardy, J. A., Cobham, V. E. & Kimble, R. Prevalence, comorbidity and course of trauma reactions in young burn-injured children. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 53, 56–63 (2012).

Mazlom, S. R., Hosseini Amiri, M., Tavoosi, S. H., Manzari, Z. S. & Mirhosseini, H. Effect of direct transcranial current stimulation on pain intensity of burn dressing. Evid. Based Care. 4, 35–46 (2015).

Hadadi Moghadam, H., Kheirkhah, M., Jamshidi Manesh, M. & Haghani, H. The impact of distraction technique on reducing the infant’s pain due to immunization. Horizon Med. Sci. 16, 0–0 (2011).

Brown, E. Psychological and Procedural Distress Following a Young Child’s Burn Injury (The University of Queensland, 2019).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. The authors extend their sincere appreciation to the administrative staff and authorities at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, as well as to all the participants who contributed to this research.

Funding

The research received support from the Vice Chancellor for Research at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran (Grant No. 18257).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.H., M.S. (second author), and M.S. (third author) participated in the conception and design of the study, contributed to data interpretation, drafting, and critically reviewed the article. M.S. (third author) implemented the intervention and played a role in data acquisition, while F.H. and M.S. (second author) were involved in data analysis. All authors have thoroughly read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hosseini, F.A., Shaygan, M. & Shayegan, M. Effects of resilience training for mothers on maternal resilience and children’s pain in pediatric burn units in a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 15, 17136 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02040-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02040-9