Abstract

This research developed an alkali-activated geopolymer (GP) cement using powdered granite waste (GW), blast furnace slag (BFS), and Zirconium aluminum Layered double hydroxide (Zr–Al–CO3 LDH). The alkali-activation reactions were promoted using NaOH and Na2SiO3 (1:1) as an alkaline activator. The durability of various GP mixes was tested by examining their mechanical properties against firing up to 800 °C and exposure to high doses of gamma rays. Results indicated that incorporating up to 30% granite powder into the GP mixture resulted in faster setting times: initial setting time decreased by 20%, and final setting time decreased by 33%. This improvement is attributed to the acceleration of alkali-activation reactions and the increased stiffness of the paste, which is due to the surplus soluble silicon ions released from the granite powder. Replacing BFS with 10% GW led to an improvement in strength by approximately 4–6%. However, increasing the replacement ratio resulted in a decline in mechanical properties. Enhancing the 80% BFS and 20% granite waste (GW) mixture with 0.5–1% of Zr–Al–CO3 LDH significantly increased compression resistance by 37% and 25% at all stages of the alkali activation process. This enhancement in compression resistance is attributed to the nano-filling effect of Zr–Al–CO3 LDH and its ability to improve the bonding between the BFS and granite particles. Furthermore, BFS (blast furnace slag) reinforced with LDH (layered double hydroxide) showed no loss of strength during durability tests against gamma-ray irradiation at doses up to 1000 kGy. Additionally, it demonstrated thermal stability when fired at temperatures up to 800 °C, in contrast to the GP mix made solely from BFS. This behavior is mainly due to the combined action of granite particles, which serve as energy storage and thermal insulating materials, with the nano-filling and/or absorptivity properties of Zr–Al–CO3 LDH within the GP matrix which reinforces the geopolymer structure to endure the detrimental impacts of these demanding environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Portland cement (PC) is considered the most effective construction material, that can be served as a binding component in traditional concrete. PC manufacturers are encountering significant challenges, including the global rise in carbon emissions, a major contributor to climate change1. Alkali-activated or geopolymer cement (GP) is an inorganic polymeric material with suitable binding properties, offering potential as a substitute for traditional cement in construction mixes2. Geopolymers (GP) are composites with cementitious properties that do not rely on Portland cement (PC). The production of Geopolymer binders does not rely on the burning of limestone, which helps reduce CO2 emissions in the vicinity3. Additionally, in the production of GPs, industrial solid waste can be used as main sources of alumina and silica to minimize their potential accumulation risks in the future4,5,6. Furthermore, geopolymer (GP) composites have excellent mechanical properties and increased resistance in acidic and corrosive environments7,8. Moreover, these cement binders showed enhanced performance when subjected to heat or radiation9,10,11,12,13,14. From an artistic perspective, GP provides a cost-effective and environmentally friendly option to Portland cement (PC) for different industrial uses. Nonetheless, the chemical makeup of the GP mix is a critical factor in establishing durability and mechanical performance.

Granite is an igneous rock composed of coarse-grained quartz, feldspars, and mica in varying proportions. Granite is a massive, hard, and tough rock with a widespread construction stone throughout human history15,16,17. Granite has many applications in the ceramic industry, such as bricks and ceramic tiles, due to its thermal stability and energy storage properties18,19. Granite waste (GW) is a byproduct formed during granite processing, constituting about 15–20% of the total mass as waste. Granite waste powder contains a high silica content, as well as alumina, iron, and magnesium oxides20. These minerals are present in an active state or can be activated either thermally or chemically. Recently, crushed granite powder can serve as a filter stone in drainage projects or for building the base for roads and pavements21,22. Many studies showed that granite rock is one of the common shielding materials used in building construction due to its high attenuation cross-section for high-energy gamma rays and neutrons23,24,25. Granite can also be seen as a natural pozzolana, and several researchers have examined its properties as supplementary cementitious materials to OPC26,27.

Layered double hydroxide (LDHs) are synthetic clays that are prepared by partial substitution of divalent cations (Ca+ 2, Zn+ 2, Mg+ 2, Co+ 2, etc.) by trivalent cations (Al+ 3, Fe+ 3 etc.), and anions are intercalated into the interlayer zone to balance the net charge28. Numerous studies have investigated LDHs and found them to be excellent adsorbents in various fields29,30. Ke et al.31 found that Mg-Al and Ca–Al LDHs can effectively resist the penetration of chloride ions through concrete pore structures in concrete mixes. However, further exploration is needed to fully utilize the ordered structure of LDH in cementitious systems, especially Zr–Al–CO3 LDH. Incorporating nano-zirconia into metakaolin-based geopolymers significantly enhances mechanical properties due to their filling action32. Incorporating zirconium in the preparation of layered double hydroxide is expected to enhance the effectiveness of the geopolymer cement to which it is added.

This study focuses on assessing the combined impact of granite powder waste (GW) and Zr–Al–CO3 LDH on the production of a highly durable and high-performance geopolymer binder. A solution mixture of Na2SiO3 and NaOH (in a 1:1 ratio) was used as the activator for the GP. The physical and mechanical properties and the performance of the geopolymer mixes prepared during firing and irradiating by gamma rays are also studied.

Experiment

Materials characterization

The materials used in this study were:

-

Ground granulated blast-furnace slag (BFS) is sourced from an iron and steel factory located in the Helwan area of Egypt. The BFS has a Blaine-specific surface area of 2883 cm2/g.

-

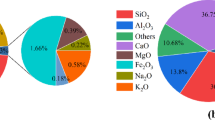

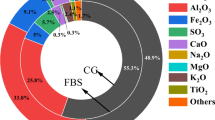

Crushed granite waste (GW) is provided from the Shuq El Thouban region. The granite powder was ground and sieved into particles sized ≤ 90 mm with a Blaine surface area of 3420 cm2/g. The mineralogical oxides composition (%) of BFS and GW is assessed by XRF (XRF, model PW-1400, Xios) which is represented in Table 1. Figure 1a, b. showed XRD diffractometry of BFS and GW. According to the XRF analysis of GW, SiO2 (68.56%) is the main oxide then Al2O3 (11.62%) and Fe2O3 (4.81%). CaO and MgO are present in low proportions. These components primarily occur as minerals such as quartz and mica in granite, as indicated in its XRD chart. These minerals contribute to granite’s thermal insulation properties. This is consistent with existing literature that highlights mica’s high thermal stability, allowing it to withstand decomposition at temperatures exceeding 1000 °C33. The main oxide composition of BFS is mainly CaO (38.33%), SiO2 (35.38%) then Al2O3 (7.11%), and MgO (5.4%). XRD diffractometry of BFS attains a broad hump between 2θ = 23–36◦, which is correlated to the amorphous and glassy nature of BFS.

-

A commercial sodium silicate and sodium derived from Al-Salam Association, 6 October District, Egypt serve as alkaline activators of the prepared GP.

Preparation of Zr–Al–CO3 LDH

Zr–Al–CO3 LDH was prepared by coprecipitation method34. 50 ml of ZrOCl2 8H2O (0.5 M) was mixed with 100 ml of AlCl3 (0.5 M) in a volume ratio 1:2 for half an hour.Na2CO3 (1 M) was used as a precipitating agent until a white emulsion was obtained at pH = 8. The obtained gel was washed with deionized water and dried at an oven at 90 °C overnight to complete the dryness of the LDH powders. Figure 2 shows a representation of the method of preparation of LDH. The morphology and texture characterization of the prepared LDH were examined via SEM/EDX techniques, in addition to the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) Surface Area Analysis and Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) pore size and volume analysis testing technique (BET/BJH), which will be discussed in “Characterization of Zr–Al–CO3 LDH” section.

GP mix design

Different blended dry powders were produced by replacing varying proportions of ground granulated blast furnace slag (BFS) with fine granite waste (GW): 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30% by mass of BFS. A mix of 80% BFS and 20% GW was strengthened with Zr–Al–CO3 LDH (0.5% or 1%). A mixture solution containing equal volumes of 6 M sodium silicate and 4 M sodium hydroxide was added to the dry mix of GP. Each dry mix was then agitated for 5 h in a porcelain ball mill to ensure the uniformity of the mixture. Table 2 provides the notation and design for each dry mix. The water-to-solid ratio (W/S) in the preparation of GP pastes was 1:2 for all samples10,11,35. Zr–Al–CO3 LDH powders were added to the GP mix as suspended particles in the prepared alkaline NaOH/Na2SiO3 solution containing 0.1% naphthalene-based dispersing agent (NB)35 and then sonicated for 20 min (Ultrasonic- LUHS0A12–220 V/50HZ, 700 W). The suspension (NaOH/H2O/NB/Zn-phase) was mixed with GP powder using an automatic ELE-automatic mixer for 3 min. After mixing the dry mixes with the alkaline solution, the resulting paste was shaped into cubic samples using molds (2.5*2.5*2.5 cm) and kept at RH ≈ 98 ± 2% for 24 hrs to start the alkali activation reactions.

Testing

-

The initial and final setting times for all the newly prepared geopolymer pastes were measured using the Vicat needle apparatus according to ASTM C19136. This apparatus consists of a frame with a movable rod with a disc on one end and a needle that can be attached to the other end.

-

The compressive strength test was conducted on three cubic samples for each geopolymer mix after 3, 14, 28, and 90 days, according to ASTM C109 M16-A37.

-

The ability of the prepared GP samples to block gamma rays was assessed on the dried 28-day sample. The examination was done by exposing the 28-days hardened samples to a gamma ray source (Co60 γ-cell-220, Atomic Energy Commission, India). The sample was exposed to doses of 250, 500, 750, 1000, and 1500 kGy at ambient temperature at a dosing rate of 1.4 kGy/hr35,38. The effect of exposing GP samples to gamma ray irradiation at varying doses on their mechanical properties was evaluated by conducting a compressive strength test, and the residual strengths (RS %) were calculated using a specific Eq. (1)10:

$$ ~~\left( {{\text{RS}}} \right)_{{{\text{rad}}}} = {\text{ }}\left( {{\text{CS}}} \right)_{{{\text{rad}}}} /\left( {{\text{CS}}} \right)_{0} ~~~ \times {\text{1}}00 f $$(1)

(CS)rad : is the compressive strength after irradiation by gamma ray, (CS)0 : is the compressive strength value before irradiation (28-day value).

-The durability of the geopolymer cement against firing was tested by exposing 28-day-old dried samples to three different firing temperatures (300 °C, 600 °C, and 800 °C) for three hours in a muffle furnace with a heating rate of 10 °C per minute10. These three temperatures were selected to observe the response of various GP samples and assess the durability of various cement hydrates under these fire exposure conditions39. After the firing test, the samples were left to gradually cooled to room temperature in closed desiccators. Subsequently, their compressive strength was tested, and the residual strength (RS)t was assessed using Eq. (2).

(C.S.)t: compressive strength after firing at heating temperature (t) .

(C.S.)0: compressive strength before firing (28-day value).

XRD (XRD, model Xpert-2000, Philips) and thermogravimetric (TGA: TA instrument, model SDT Q600) techniques were used to identify the phases formed during the hydration of various geopolymer samples. X-ray Diffraction (XRD) was conducted using a cobalt target (λ = 0.17889 nm) and a nickel filter, operating at 40 kV and 40 mA. The scanning range extended from 5° to 60° (2θ), with a scanning speed of 1 s per step and a resolution of 0.02 per step. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) was performed using a TGA-TG instrument, model SDT Q600. A nitrogen environment was maintained while heating 15 mg of powdered sample (≤ 25 μm) over a temperature range of 50 °C to 1000 °C, with a heating rate of 10 °C per minute. To examine microstructural development, Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) was utilized, along with Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDX) for elemental analysis. The SEM device used was a Quanta 250 FEG. To prevent electron accumulation and ensure electrical conductivity, a thin layer of gold was applied to the sample prior to capturing the SEM images.

Figure 3 provides a graphical representation of the methodology.

Results and discussion

Characterization of Zr–Al–CO3 LDH

The morphology and surface characteristics of the prepared Zr–Al–CO3 LDH were studied using SEM/EDX and N2-adsorption/desorption techniques. The SEM image of the Zr–Al–CO3LDH, shown in Fig. 4, revealed there are two crystal shapes: hexagonal crystals and fibers (which appeared as nano-rods). These two types of crystals are strongly interconnected and form a well-developed layered structure40. The elemental analysis (EDX spectrum) for Zr–Al–CO3LDH is 18.3% (Zr), 35.40% (O), 41% (C), and 9.2% (Al) which is the stoichiometric formula for Zr–Al–CO3 LDH39. (BET/BJH) models were utilized to examine the texture characterization and pore size distribution of the prepared LDH nanolayers41.

Adsorption/desorption isotherm of Zr–Al–CO3 LDH, Fig. 5a, displays type 2 with a small H1 hysteresis loop according to IUPAC classifications which confirms the mesoporous/microporous nature of Zr–Al–CO3 LDH40. The texture parameters of Zr–Al–CO3 LDH were SBET = 192 m2/g, average pore diameter = 12.77 nm, and total pore volume (Vp) = 0.677cm3. Figure 5b shows BJH curve for LDH which shows the maximum pore size value (dpmax = 28 nm). The high surface area and the tiny particle size of the prepared LDH confirm the great contribution of LDH to catalyzing the alkali-activation reactions of the created geopolymer binder.

Setting times

The initial and final setting times of different GP formulations play a crucial role in determining how tested materials are handled and where they can be used. In Fig. 6, you can see that the control mix had initial and final setting times of 55 and 85 min, respectively. When ground granulated blast furnace slag (BFS) was replaced by granite powder (GW), the setting times decreased by 6 to 20% for the initial setting time and by 13 to 33% for the final setting time. The reduction in setting times is due to the high silica content in the GP formulation due to the replacement of BFS (which has a high calcium content) with GW (which has a high silica content). The elevated silica content encourages the rapid release of silica ions when the alkaline activator is introduced. The free silica ions interact with the calcium ions to initiate rapidly the formation of the GP networks. Furthermore, the high silica content in GP paste rapidly removes water from the matrix, leading to an acceleration in the setting process10,42. Such finding matches that of Khale and Chaudhary’s investigation, which studied the impact of silica ions on the geopolymer mechanism. They found that a high silica content facilitates the rapid release of silica ions when the alkaline activator is introduced. These ions then interact with the calcium ions to initiate the formation of the GP networks43.

Amelioration of GP mix by 0.5 or 1% of Zr–Al–CO3 layer double hydroxide results in a further reduction in the setting times to be in case mix M2-LDH1, 34 and 58 min for initial and final setting times respectively while mix M20-LDH2 recorded 31 and 55 min. This accelerated setting process is due to the acceleration impact of Al3+ and Zr 2+ metal ions released from the partial dissolution of LDH at a high pH medium. Gohi et al. clarified that at pH around 11.5, the partial dissolution of Zr-Al LDH can release Al3+ metal ions beside Zr2+ metal ions44. The release of Al3+ metal ions can contribute to forming further amounts from strength-giving-phases such as CAH and CASH44. Additionally, Zr–Al–CO3 LDH can act as active nucleation sites that catalyze the alkali-activation reaction, giving extra strength-binding phases. The impact of Zr–Al–CO3 layered double hydroxide (LDH) on the setting behavior of BFS/GW geopolymer is comparable to that of other nano additives, such as nano-silica and nano-clays45. Research has demonstrated that these materials function through similar mechanisms, primarily due to their high surface area and fine particle size, which enhance their catalytic action. This action promotes the dissolution of geopolymer oligomers and accelerates the geopolymerization process.

Compressive strength

Figure 7 shows the compressive strength (measured in MPa) of various GP formulations after 3,14,28 and 90 days. The compressive strength of the control mix (100% BFS, Mix M0) increases consistently over time, with approximately 65% of the strength achieved within the first 14 days. In the initial stage of alkali activation, the alkaline mixture (blend of Na2SiO3 and NaOH) partially dissolves the BFS particles, releasing active components and facilitating the activation reactions. These reactions create strength-giving phases, such as calcium-silicate-hydrate (C-S-H) and calcium-substituted sodium-aluminosilicate-hydrate (N-C-A-S-H) gels33,34,46. Over time, these phases transform into a more thermodynamically stable form known as calcium-aluminate-silicate-hydrate (C-A-S-H) gel. Both calcium-silicate-hydrate and calcium-aluminate-silicate-hydrate built up the GP network and positively impacted its mechanical properties. According to the literature, forming C-A-S-H acting as micro-nucleation sites in the geopolymer gel, in which more hydrates are formed, resulting in a denser and more uniform binder47.

Replacing 10% of BFS with GW led to a 7 to 10% increase in strength values across all curing times. This improvement is due to the release of Si ions from the substituted granite waste powder with the shortage of Ca ions (results from BFS) in the GP system, The replacement of GW increases the Si/Al ratio while decreasing the Ca/Al ratio in the geopolymer (GP) matrix. This change promotes the formation of more N-A-S-H gel instead of C-S-H gel. According to the literature, the presence of N-A-S-H gel influences the microstructure and, consequently, the engineering properties of geopolymers. Furthermore, the more soluble silicon can interact with calcium ions from blast furnace slag (BFS), leading to the formation of greater quantities of strength-enhancing phases such as C-A-S-H and N-C-A-S-H. The N-C-A-S-H phase has a three-dimensional reticulated structure, which can create an organized two-dimensional or three-dimensional inorganic network with improved mechanical properties48. At 20 and 30% replacement, the compressive strength diminished by 15 and 50% for M20 and M30 respectively after 90 days. This decrease can be attributed to the dilution effect caused by blending BFS with 20% GW. This blending decreased calcium content, a key factor for promoting GP reactions, sourced from BFS which was replaced by Granite powder (has high silica content)21. In M20 and M30 mixes, the Ca contents were insufficient for forming considerable quantities of strength-giving phases (CSH and CASH). Shilar et al. reported that the increase in the GW content in the mix increases the compressive strength up to 10%, and beyond 20% CS declined21. The suitable proportion of GW in the GP mix results in more silica gel that promotes the production of denser Si–O–Si linkages during polymerization provided49. High GW content adversely affects the matrix structure of geopolymer composites, hindering the silica gel formation. Excess silicate delays water evaporation during polycondensation and detriment the compression resistance50,51,52.

When 80% BFS and 20% granite are mixed with 0.5% or 1% Zr–Al–CO3 LDH particles (as mixes M20-LDH1 and M20-LDH2), it leads to significantly improved compression resistance. The mix with a 1% addition performs better than a 0.5% addition, showing a 25% improvement in strength for M20-LDH1 and a 35% improvement for M20-LDH2 after 90 days compared to their counterparts without LDH. The improvement finding is mainly attributed to the nano-filling effect and the nucleation/catalytic properties of Zr–Al–CO3LDH, which result in the formation of additional hydration products that refine the microstructure. According to Vanitha et al., nano additives have been found to speed up the growth of alkali-activation gel and the filling of tiny pores42. It is worth noting that Zr–Al–CO3 LDH has a large specific surface area (192 m2/g) and functions as a solid binder, facilitating the connection between the BFS/granite particles50. Additionally, Zr–Al–CO3 LDH can release the CO3 ions which refine the GP matrix51. All these factors explain the increase in the strength of the M20-LDH mixes compared to their control mix.

Durability tests

Gamma-ray shielding

The ability of construction materials to shield destructive rays, such as gamma rays, depends on their structural formulation, porosity, microstructure, their included phases, curing conditions, and the power of the applied rays53,54. The linear attenuation coefficient (µ, cm− 1) is one of the most important metrics for determining the radiation shielding capabilities of any material. The attenuation coefficient represents the fraction of an energy beam that is absorbed or scattered per unit thickness of the medium. The linear attenuation coefficients after 28 days of curing were measured to evaluate the shielding capability of M0, M20, M20-LDH1, and M20-LDH2 mixes against gamma rays. In Fig. 8a, the linear attenuation coefficients were shown after irradiation using a γ-ray source (60Co-γ-cell-220, Atomic Energy Commission, Canada) of various intensities (250, 500, 750, 1000, and 1500 kGy). The µ value decreases as the power of the gamma rays increases for all the studied GP mixes. Moreover, the blended mixes exhibited higher linear attenuation coefficients than the control mix (M0) at all the tested powers of gamma rays. According to Abdalla et al. who studied the shielding properties of granite rocks of various thicknesses against different powers of gamma rays. They found that the granite rock under study has high attenuating effectiveness and shielding properties against gamma rays at low energy54. To study the destructive effect of the irradiation by gamma ray, the residual strength of the tested cubes after exposure was measured. Figure 8b displayed the relation between the residual strength (RS)rad after irradiation by gamma rays of intensities 500, 1000, and 1500 kGy. The control mix (M0) exhibited a declining trend in residual strength RSrad as the power of the irradiated γ-rays increased. There was an 18.5–35% decrease in compression strength in the M0 mix due to the exposure to gamma rays at powers of 500 and 1500 kGy, respectively. This decline in strength may be attributed to the negative effect of the irradiated rays on creating a loose structure55. In contrast, the blended mixes containing granite powders (M20) showed an improvement in residual strength by 3% when irradiated by gamma rays of power 500 kGy compared to the strength measured before irradiation (the value at 28 days of curing). While irradiation by powers 1000 and 1500 kGy, the RSrad decreases by 9 and 12% respectively but is still higher than those recorded by the control mix at the same powers of gamma rays. For the binary blended mixes containing LDH and granite powders, M20-LDH1 & M20-LDH2, the residual strength highly improved by 9 & 8% at 500 kGy irradiation and 2% for the power 1000 kGy of irradiated gamma rays. This behavior results from multiple factors that enhance the shielding properties of these blends. The primary factor is the energy storage properties of GW, which resist the destructive effects of harmful gamma rays. According to Obaid et al. and others, the granite rocks have a considerable shielding efficiency for gamma with high energy, and they can be recommended as suitable alternatives for gamma-ray shielding applications in nuclear reactors and research facilities56. Besides, the cross-linking occurred in the linear alumino-silicate chains in an alkali-activated matrix caused by gamma-ray irradiation10,57. This process leads to the formation of additional hydration products that fill the pores and enhance the compression resistance. Furthermore, the LDH nanosheets’ filling and catalytic properties, along with their ability to connect between the hydration products, enable the formation of a denser GP microstructure with higher resistance to the damaging effects of gamma rays. At the 1500 kGy level, these composite mixes experience a 7% and 8% reduction in compression resistance for M20-LDH1 and M20-LDH2, respectively. However, they still demonstrate a better performance than the control mix (M0, 35% loss) or their counterpart without LDH (M20,12% loss). It is worth noting that the fabricated BFS/GW reinforced by Zr–Al–CO3 LDH showed higher stability in gamma-ray irradiation than other GP composites, such as metakaolin-based geopolymer57,58 and slag-based geopolymer cement59,60.

Firing test

Figure 9 illustrates the residual strength (RS%)t for specimens M0, M20, and M20-LDH2 after being subjected to firing at 300 °C, 600 °C, and 800 °C for three hours, and then cooling gradually in desiccators to room temperature. It has been observed that there is an increase in compressive strength in all the tested mixes when they are fired at 300 °C compared to their original strength (28-day values). When a hardened geopolymer mix is heated to 300 °C, the steam pressure inside the matrix increases. This steam pressure acts as self-autoclaving process that activates the unreacted geopolymer precursors leading to the progression of the alkali activation reactions and cross-linking of the geopolymer network through the alkaline hydroxyl anions10,34,61. These activation processes lead to the accumulation of hydrates in the pore system of the geopolymer matrix, ultimately improving its compression resistance62. After being fired at 600 °C, all the mixtures displayed a slightly decreased compressive strength. Among the mixtures tested, M20-LDH2 exhibited the highest remaining strength. The residual strength recorded by M20-LDH2 mix can be attributed to the combined effects of the filling and nucleation properties of LDH particles, as well as the thermal insulation properties of the fine granite powder63,64. The high fire resistance of the M20-LDH2 mix is still noticeable even after exposure to temperatures of 800 °C. Although the control mix (M0) showed a significant decrease in compressive strength when fired at 800 °C (RSt =49.2%), the blended mixes still provided higher RSt than mix M0, with mix M20-LDH2 being the best (RS = 65%). At 800◦C, dehydration/ dehydroxlation of all the formed hydrates occurred leading to the formation of micro-cracks and the opening of pores due to high pressure inside the pore matrix resulting in a great depletion in the mechanical properties and reduction in RSt for all mixes. The thermal insulation properties of fine granite can reduce these destructive actions and retain some of its mechanical properties65. It is important to note that the firing resistance of the fabricated GP composite is comparable to that of Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC), particularly at high temperatures of 600 °C and 800 °C. According to earlier studies, OPC-hardened pastes lost 21% of their original strength at 600 °C and 47% at 800 °C respectively58.

Phase composition

XRD

XRD testing was conducted to identify the phases resulting from alkali-activation reactions in different GP formulations. Figures 10 and 11 displayed XRD patterns for mixes M0, M20, and M20-LDH2 after 28 days of alkali activation reactions and firing at 300 & 800 °C. According to XRD patterns, the M0 pattern showed peaks were distinguished for unreacted phases like calcite (PDF# 01–088–180) which appeared at 2θ= 36.2, 39.91, 47.1, and 50.67, quartz (PDF#01–087–2096) at 2θ= 21.4 and 26.81◦. The hydrated phases had also appeared in XRD patterns of all samples as the ill-crystalline phases of CSHs (PDF# 00–033–0306) appeared as humps at 2θ= 26.17 and 29.07° and hydrogarnet (CASHs: PDF# 00–020–0452) appeared at 2θ= 26,8 °and 31.23. Besides, a small peak appeared at 31.54 and 33.4° assigned to amorphous NASHs (PDF# 00–039–0217). These phases were generated as the main alkali activation products in the control sample in which CASH acts as nucleation sites for the geopolymerization process10,44,66. While, CSHs built the primary structure of solid materials, marking the start of the hardening process67. M20 and M20-LDH2 displayed the same hydrated phases as the control mix, M0. The main observation is the decrease in intensities of the peaks assigned to amorphous CSHs, making them less visible, while those for CASH and NASHs became more intense. The C-S-H gel was likely C-A-S-H or C-(N)-A-S-H gel, which aided in geopolymerization and enhanced the mechanical performance in the composite samples. For M20-LDH2 mix, the XRD pattern showed additional peaks assigned to Zr- alumino-silicate-hydrates (ZASH, PDF 01–088–2370) at 2θ = 22.1, 28.3° which formed due to the interaction of Zr ions liberated from the LDH with the GP matrix64. Zr ions can replace Ca in the CASH phase to form its analog ZrASH. Additionally, there are increased intensities of the hydrated phases in mix M20-LDH2 which confirms the effect of adding Zr–Al–CO3 LDH for forming more hydrated and improving the strength.

Figure 11 shows the main phases of the various mixes after firing at 800 °C for three hours. The main observation of the XRD patterns for samples fired at 800 °C is the increased intensities of the peaks assigned to unhydrous phases as; quartz and calcite and the broadening with a reduction in their intensities of the peaks of the hardened phases like; CSH, CASH, and NASH. Most of the GP hydration products were de-calcinated at this high temperature as shown in XRD patterns of all mixes. M20 and M20-LDH2 showed higher intensities for CSHs, and NASH compared to those in M0 mix, which confirms the high resistivity against firing at high temperatures for these two composites compared to the control mix. This resistance toward firing at extremely high temperatures may be related to the thermal insulation properties of granite powders (as in M20 mix) and/or the Plenty of hydration products (as in M20-LDH2 mix)68,69.

Thermal study

Figure 12a&b shows TG/DTG curves for mixes M0 and M20-LDH2 after 28 days of curing. There is a continued decrease in mass loss (%) for the two mixes studied by heating up to 900 °C. TG/DTG curves can be divided into three stages of mass loss, at three ranges of temperatures: 50–300 °C, 300–600 °C, and 600–900 °C. The first stage of mass loss (50–300 °C) is related to the removal of water (free, physically adsorbed, and chemically combined) occurred with the dehydration of CSHs gel/semicrystalline, the disintegration of the C-A-S-H (including the gehlenite phase, C2ASH8), as well as the thermal breakdown of sodium -aluminate-silicate-hydrates (NASH)70,71. For M20-LDH, there is an increase in the percent of mass loss from 4.4 to 7.08% indicating the formation of more previously mentioned hydrates in this mix as well as ZrASH phase due to the release of Zr ions from LDH and their interaction with GP hydrates. At the second thermal decomposition stage (300–600ºC), the decomposition of the hydrocalumite, (C4ASH4) and calcium-aluminate-hydrates (C3AH6) occurred72,73. Again, M20-LDH2 mix recorded the highest mass loss (7.02%) while the control mix showed 3.8%. This confirms the effects of Zr-LDH in forming more hydrates which aligns with the mechanical behavior of this mix. The third stage, between 600 °C and 900 °C, is associated with the carbonation of samples during handling74.

The Derivative Thermal Gravimetry (DTG) study revealed two main endothermic peaks, which represent the main phases present in these mixtures. The first broad endothermic peak occurs between 50 and 220 °C, centered at 205 °C, and is associated with the continued evaporation of free water and weakly adsorbed water inside the geopolymer gel pores75. The second endotherm, observed at 230–450 °C with a peak intensity at 400 °C, suggests the disintegration of the most thermally stable binding phases, including C-A-S-H (hydrogarnet, C3ASH4), and the stable cubic phase of C-A-H as C3AH676. M20-LDH2 showed broadening with an increased intensity in this endotherm.

Microstructure

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) analysis SEM were used to explore the microstructure and the morphology of the hydrates formed during the alkali-activation reaction of GP mixes. Figure 13a and b showed the SEM/EDX analysis of mixes M0 and M20-LDH2 after 28 days of curing. Notably, a compact structure composed mainly of semi-crystalline CSHs fibers which appeared as tiny rods is interconnected with pyramidal-like crystals for CASH (Al-Tobormorite) that appeared in the M0 image. These types of hydrates are responsible for the geopolymer matrix’s solidified structure, which is the main reason for the obtained strength75,76. EDX qualitative/semi-quantitive analysis of that image showed the chemical composition of the GP matrix composed mainly from; O, Ca, Si, Al, Na, and Mg elements with Ca/Si, Ca/Al, and Na/Al ratios: 1.45, 2.17 and 0.43 respectively. These ratios are the stoichiometric compositions of CSHs gels, CASH, and NASH respectively77. For mix M20-LDH2, numerous pyramidal/plate-like crystals of CASH interconnected in CSH fibers appeared in its SEM image. Besides, large quantities of stacked Zr(OH)2 flakes are shown, which formed due to the reaction of Zr ions with OH− ions inside the GP matrix. EDX analysis of the hydrates formed in the M20-LDH2 mix showed increases in the percent of O, Ca, and Si elements with the Ca/Si and Ca/Al ratios 1.65 and 3.5 respectively. This affirms the role Zr–Al–CO3 LDH for catalytic alkali-activation reactions and forms extra quantities of CSH & CASH which are strength-giving phases in the GP mix.

Conclusions

In the present research, we demonstrated the use of blast furnace slag (BFS), and granite powder waste (GW) combined with Zr–Al–CO3 LDH in the development of geopolymer (GP) composites with satisfactory mechanical characteristics and durable performance. The key conclusions drawn from our findings are as follows:

-

1.

The blending of BFS with GW shortens the setting times due to the release of additional Si ions in the GP formulation which increases the water absorptivity and stiffness of the paste. Amelioration of GP mixes by Zr–Al–CO3 LDH greatly accelerates the setting process.

-

2.

Up to 10% blending of GP by GW, the compression resistance improved by 7 to 10% in all the curing times, this is attributed to the presence of suitable Ca and Si ions in GP formulation for forming 2D or 3D geopolymer network for improved mechanical properties.

-

3.

20 and 30% replacement of BFS by GW reduced the strength due to the reduction in Ca ions via blending and formation of insufficient strength-giving phases (CSH and CASH).

-

4.

Amelioration of GP formulation by 0.5 or 1% Zr–Al–CO3 LDH enhances its mechanical properties at all curing periods by about 25 to 35%.

-

5.

BFS/GW mixes have good durability in both firing action and irradiation against gamma rays. This is related to the thermal insulation properties and the energy storage properties of granite phases.

-

6.

The BFS/GW reinforced by Zr–Al–CO3 LDH showed superior resistance against the firing action and the destructive effects of irradiation by high doses (1000 and 1500 kGy) of gamma rays.

-

7.

Such high durability is related to the combined effect of GW which acts as a thermal insulator material and energy storage material as well as the catalytic action/ filling properties of Zr–Al–CO3 LDH nanosheets. This combined action resulted in the formation of extra hydration products that refine the GP matrix and improve the microstructure. According to our study, geopolymer cement composites reinforced with LDH may exhibit improved properties, making them a novel and promising building material.

-

8.

BFS/GW reinforcement by Zr–Al–CO3 LDH geopolymer cement can have a wide range of applications as thermal tiles, shielding applications in nuclear reactors and lining of hospital radiation rooms.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

14 July 2025

This article has been updated to amend the license information.

References

Nie, S. et al. Analysis of theoretical carbon dioxide emissions from cement production: Methodology and application. J. Clean. Prod. 334, 130270 (2022).

Elyamany, H. E., Abd Elmoaty, A. E. M. & Elshaboury, A. M. The durability of alkali-activated materials in comparison with ordinary Portland cements and concretes: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 184, 111–127 (2018).

Ren, A., Lai, Y. & Gao, J. Exploring the influence of SiO2 and TiO2 nanoparticles on the mechanical properties of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 30 175, 277–285 (2018).

Hazem, M., Hashem, F. S., Amin, M. S. & El-Gamal, S. M. A. Mechanical and microstructure characteristics development of hardened oil well cement pastes incorporating fly ash and silica fume at elevated temperature. J. Taib Univer Sci. 4(1), 155–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/16583655.2020.1711998 (2020).

Mohamed, H., Morsi, A. E. A. S. & W.M Characteristics of blended cements containing nano-silica. HBRC 9, 243–255 (2013).

Nazari, N. & Riahi, S. The role of SiO2 nanoparticles and ground granulated blast furnace slag admixtures on physical, thermal and mechanical properties of self-compacting concrete. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 528, 2149–2157 (2011).

Li, G. Properties of high-volume fly ash concrete incorporating nano-SiO2. Cem. Concr. Res. 34, 1043–1094 (2004).

Thuadaij, N. & Nuntiya, A. Preparation of nano silica powder from rice husk ash by precipitation method. Chiang Mai J. Sci. 35, 206–211 (2008).

El-Gamal, S. M. A., Hashem & F.S. Enhancing the thermal resistance and mechanical properties of hardened Portland cement pastes by using pumice and al. J. Therm. Analy Calorim 128, 15–27 (2017).

Mashout, H. A., Razek, T. A., Amin, M. S. & Hashem, F. S. Performance of nano titania-reinforced slag/basalt geopolymer composites. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 70, 106. https://doi.org/10.1186/s44147-023-00278-6 (2023).

Monir, D., Selim, F., Hazem, M. & Hashem, F. S. Geopolymer cement composite containing agriculture solid wastes: Mechanical and durability performance. HBRC J. https://doi.org/10.1080/16874048.2024.2318503 (2024).

Liu, Q., Li, X., Cui, M., Wang, J. & Lyu, X. Preparation of eco-friendly one-part geopolymers from gold mine tailings by alkaline hydrothermal activation. J. Clean. Prod. 298, 126806 (2021).

Abd Elmoaty, A. E. M. Mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of concrete modified with granite dust. Constr. Build. Mater. 47(2013) 743–752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.05.054 (2013)

Adjei, S., Elkatatny, S. & Sarmah, P. Evaluation of granite waste powder as an oil-well cement extender, Arab. J. Sci. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-022-07550-6 (2023).

Ramadji, C., Messan, A. & Prud’Homme, E. Influence of granite powder on Physico- mechanical and durability properties of mortar. Materials 13, 5406. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13235406 (2020).

Dassekpo, J. B. M., Zha, X. & Zhan, J. Compressive strength performance of geopolymer paste derived from completely decomposed granite (CDG) and partial fly ash replacement. Constr. Build. Mater. 138, 195–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.01.133 (2017).

Vasi´c, M. V., Mijatovi´c, N. & Radojevi´c, Z. Aplitic granite waste as Raw material for the production of outdoor ceramic floor tiles. Mater 15(9), 3145. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15093145 (2022).

Terrones-Saeta, J. M., Suarez-Macías, J., Corpas-Iglesias, F. A., Korobiichuk, V. & Shamrai, V. Development of ceramic materials for the manufacture of bricks with stone cutting sludge from granite. Mineral 10(7), 621. https://doi.org/10.3390/min10070621 (2020).

Jiang, C. C., Huang, S. F., Li, G. Z., Zhang, X. Z. & Chen, X. Formation of closed-pore foam ceramic from granite scraps. Ceram. Int. 44(3), 3469–3471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2017.10.180 (2018).

Gupta, L. K. & Vyas, A. K. Impact on mechanical properties of cement sand mortar containing waste granite powder. Constr. Build. Mater. 191, 155–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.09.203 (2018).

Shilar, F. A. et al. Evaluation of the effect of granite waste powder by varying the molarity of activator on the mechanical properties of ground granulated blast-furnace slag-based geopolymer concrete. Polymers 14, 306 https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14020306 (2022).

Shih, J. Y., Chang, T. P. & Hsiao, T. Effect of nano silica on characterization of Portland cement composite. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 424, 266–274 (2006).

Askin, A. & Dal, M. Assessment of the mass Attenuation coefficients of granite, basalt, andesite and tuff stones with the Geant4 model of a high-purity germanium detector. Pramana - J. Phys. 93 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12043-019-1780-9 (2019).

Çelen, Y. Y., Akkurt, L., Ceylan, Y., Atçeken, H. & H Application of experiment and simulation to estimate the radiation shielding capacity of various rocks. Arab. J. Geosci. 14 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-021-08000-7 (2021).

Alorfi, H. S., Hussein, M. A. & Tijani, S. A. The use of rocks in lieu of bricks and concrete as radiation shielding barriers at low gamma and nuclear medicine energies. Construct Build. Mater. 251, 118908. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118908 (2020).

He, X-Y. et al. A novel ZnWO4/MgWO4 n-n heterojunction with enhanced sonocatalytic performance for the removal of methylene blue: Characterizations and nanocatalytic mechanism surf. Interfaces 31, 101980 (2022).

Wu, B., Zuo, J., Dong, B., Xing, F. & Luo, C. Study on the affinity sequence between inhibitor ions and chloride ions in MgAl layer double hydroxides and their effects on corrosion protection for carbon steel. Appl. Clay Sci. 180, 105181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2019.105181 (2019).

Xu, S., Zhao, J., Yu, Q., Qiu, X. & Sasaki, K. Understanding how specific functional groups in humic acid affect the sorption mechanisms of different calcinated layered double hydroxides. Chem. Eng. J. 392, 123633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2019.123633 (2020).

Chen, G. et al. Combination of LDHs and metakaolin for improving the sulfate ion resistance of concrete. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. 36, 1–5 (2014).

Wang, C., Kong, F. & Pan, L. Effects of polycarboxylate superplasticizers with different side-chain lengths on the resistance of concrete to chloride penetration and sulfate attack. J. Build. Eng. 43, 102817 (2021).

Ke, X., Bernal, S. A. & Provis, J. L. Uptake of chloride and carbonate by Mg-Al and CaAl layered double hydroxides in simulated pore solutions of alkali-activated slag cement. Cem. Concr Res. 1001–1013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2017.05.015 (2017).

Saukani, M. et al. Effect of nano-zirconia addition on mechanical properties of metakaolin-based geopolymer. J. Compos. Sci. 6, 293. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs6100293 (2022).

Agasnalli, C., Hema, H. C., Lakkundi, T. & Chandrappa, K. D. Integrated assessment of granite and basalt rocks as Building materials. Mater. Today 62(8), 5388–5391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2022.03.546 (2022).

Brahma, D. & Saikia, H. Synthesis of ZrO2/MgAl-LDH composites and evaluation of its isotherm, kinetics and thermodynamic properties in the adsorption of congo red dye. Chem. Thermo Therm. Anal. 7, 100067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctta.2022.100067 (2022).

Hashem, F. S., Abd El-Razek, T., Mashout, H. & Selim, F. A. Fabrication of Slag/CKD One- mix geopolymer cement reinforced by low- cost nano-particles, mechanical behavior, and durability performance. Sci. Rep. (49) 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-53023-1 (2024).

ASTM standards. Standard test method for time of setting of hydraulic cement by Vicat needle. ASTM C191:208. ASTM International. (1983).

ASTM. Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Hydraulic Cement Mortars109 (ASTM Inter. West Conshohocken, 2008).

Öztürk, B. C., Kızıltepe, C. Ç., Ozden, B., Güler, E. & Aydın, S. Gamma and neutron attenuation properties of alkali-activated cement mortars. Radia Phy Chem. 166, 108478 (2020).

ASTM E119-20. Standard Test Methods for Fire Tests of Building Construction and Materials, ASTM International.10.1520/E0119-20 (2022).

Poonoosamy, J., Brandt, F. & Stekiel, M. M. Zr-containing layered double hydroxide: synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of thermodynamic properties. Appl. Clay Sci. 151, 54–65 (2018).

Bardestani, R., Gregory, S. P. & Kaliaguine, S. Experimental methods in chemical engineering: specific surface area and pore size distribution measurements—BET, BJH, and DFT, can. J. Chem. Eng. 97, 2781–2791. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjce.23632 (2019).

Vanitha, N., Revathi, T., Sivasakthi, M. & Jeyalakshmi, R. Microstructure properties of poly(phospho-siloxo) geopolymeric network with Metakaolin as sole binder reinforced with n-SiO2 and n-Al2O3. J. Sol Stat. Chem. 312 123188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2022.123188 (2022).

Khale, D. Chaudhary R. Mechanism of geopolymer-ization and factors influencing its development: A review. J. Mater. 42 (3) 729–746 (2007).

Gohi, B. F. et al. Optimization of ZnAl/chitosan supra-nano hybrid preparation as efficient antibacterial material. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14(20), 22–5705 (2019).

Jindal, B. & Sharma, R. The effect of nanomaterials on properties of geopolymers derived from industrial by-products: A state-of-the-art review. Constr. Build. Mater. 119028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119028 (2020).

Mohsen, A., Abdel-Gawwad, H. A. & Ramadan, M. Performance, radiation shielding, and anti-fungal activity of alkali-activated slag individually modified with zinc oxide and zinc ferrite nanoparticles. Constr. Build. Mater. 257, 119584 (2020).

Gla, B. et al. Compatibility studies between N-A-S-H and C-A-S-H gels. Study in the ternary diagram Na2O-CaO-Al2O3-SiO2-H2O, Cem. Concr Res. 41(9), 923–931 (2011).

Zhao, X. et al. Investigation into the effect of calcium on the existence form of geopolymerized gel product of fly Ash based geopolymers. Cem. Concr Compos. 103, 279–292 (2019).

Amran, Y. H., Alyousef, R., Alabduljabbar, H. & El-Zeadani, M. Clean production and properties of geopolymer concrete—A review. J. Clean. Prod. 251, 119679 (2020).

AlKhatib, A., Maslehuddin, M. & Al-Dulaijan, S. U. Development of high-performance concrete using industrial waste materials and nano-silica. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 9, 6696–6711 (2020).

Hashem, F. S., Fadel, O., Selim, F. & Hassan, H. S. Examining the effect of hybrid activator on the strength and durability of slag-fine metakaolin based geopolymer cement. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scp.2024.101890 (2025). .43101890.

Hassan, H. S., Chi, S., Hashem, F. S., Alcantara, I. I. & Pfeiffer, H. Exploring diatomite as a novel natural resource for ecofriendly-sustainable hybrid cements. Resour. Conser Recy 202 107402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2023.107402 (2024).

Ababneh, F. A., Alakhras, A. I., Heikal, M. & Ibrahim, S. M. Stabilization of lead bearing sludge by utilization in fly ash-slag based geopolymer. Constr. Build. Mater. 227, 116694 (2019).

Amin, M. S., El-Gamal, S. M. A. & Hashem, F. S. Fire resistance and mechanical properties of carbon nanotubes – clay bricks wastes (Homra) composites cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 98, 237–249 (2015).

Garg, A. et al. Durability studies on conventional concrete and slag-based geopolymer concrete in aggressive sulphate environment. Energy Ecol. Environ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40974-023-00300-w (2023).

Obaid, S. S., Sayyed, M. I., Gaikwad, D. K. & Pawar, P. P. Attenuation coefficients and exposure buildup factor of some rocks for gamma ray shielding applications. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 148, 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radphyschem.2018.02.026 (2018).

Geddes, D. A. et al. Effect of exposure of metakaolin-based geopolymer cements to gamma radiation. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 107, 4621–4630. https://doi.org/10.1111/jace.19747 (2024).

Hashem, F. S., Hekal, E. E., Abdel Naby, M. M. & Selim, F. A. Mechanical properties and durability performance against fire, gamma ray and bio-fouling of hardened Portland cement pastes incorporating lead bearing wastes. Mater. Chem. Phys. 272, 124–997 (2021).

Hassan, M. W., Sugiharto, S. & Astutiningsih, S. Gamma radiation shielding properties of slag and fly ash-based geopolymers. Atom Indonesia 47(3), 173–180 (2021).

Abdalla, A. M., Al-Naggar, T. I., Bashiri, A. M. & Alsareii, S. A. Radiation shielding performance for local granites. Prog Nucl. Enery. 150, 104294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnucene.2022.104294 (2022).

Arivumangai, A. & Felixkala, T. Strength and durability properties of granite powder concrete. J. Civ. Eng. Res. 4, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.5923/c.jce.201401.01 (2014).

Fadel, O., Hehal, E. E., Hashem, F. S. & Selim, F. A. Mechanical properties, resistance to fire and durability for sulfate ions of alkali activated cement made from blast furnace slag- fine metakaolin. Egypt. J. Chem. 63, 4821–4831 (2019).

Baiyi, L. & Feng, J. Thermal stability of granite for high-temperature thermal energy storage in concentrating solar power plants. App Therm. Eng. 138, 25 409–416 (2018).

Chen, Y. L., Ni, J., Shao, W. & Azzamb, R. Experimental study on the influence of temperature on the mechanical properties of granite under uniaxial compression and fatigue loading int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 56, 62–66 (2012).

Fu, Q. et al. The microstructure and durability of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete: A review. Ceram. Intern. 47 21, 29550–29566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.07.190 (2021).

Nematollahi, B., Sanjayan, J. & Shaikh, F. U. A. Synthesis of heat and ambient cured one-part geopolymer mixes with different grades of sodium silicate. Ceram. Int. 41, 5696–5704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2018.04.071 (2015).

Zheng, S., Chen, J. & Wang, W. Effects of fines content on durability of high-strength manufactured sand concrete. Materials 16, 522. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16020522 (2023).

Qiu, Z. et al. Effect of Portland cement on the properties of geopolymers prepared from granite powder and fly Ash by alkali-thermal activation. J. Build. Eng. 76, 107363 (2023).

Selim, F. A., Hashem, F. S. & Amin, M. S. Mechanical, micro-structural and acid resistance aspects of improved hardened Portland cement pastes incorporating marble dust and fine kaolinite sand. Const. Build. Mater. 251, 118992 (2020).

Khalid, S. et al. Analysis of strength and durability properties of ternary blended geopolymer concrete. Mater. Today Proc. 54 259–263. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2021.08.307

Zawrah, M. F., Gado, R. & Khattab, R. Optimization of slag content and properties improvement of metakaolin-slag geopolymer mixes. Open. Mater. Sci. J. 12(1) (2018).

Zawrah, M. F. et al. Fabrication and characterization of non-foamed and foamed geopolymers from industrial waste clays. Ceram. Int. 47(29), 320–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.07.097 (2021).

Farhan, K. Z., Johari, M. A. M. & Demirboğa, R. Evaluation of properties of steel fiber reinforced GGBFS-based geopolymer composites in aggressive environments. Constr. Build. Mater. 345, 128339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.128339 (2022).

Vakalova, T. V., Devyashina, L. P., Sharafeev, S. M. & Sergeev, N. P. Phase formation, structure and properties of light-weight aluminosilicate proppants based on claydiabase and clay-granite binary mixes. Ceram. Int. Ceram. Int. 47(11), 15282–15292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.02.092 (2021).

Abo-El-Enein, S. A., Hashem, F. S., Amin, M. S. & Sayed, D. M. Physicochemical characteristics of cementitious building materials derived from industrial solid wastes. Constr. Build. Mater. 126, 983–990 (2016).

Amin, M. S. & Hashem, F. S. Hydration characteristics of hydrothermal treated cement kiln dust–sludge–silica fume pastes. Constr. Build. Mater. 5, 1870–1876 (2011).

Amin, M. S. et al. Evaluation of mechanical performance, corrosion behavior, texture characterization and aggressive attack of OPC-FMK blended cement pastes modified with micro Titania. Constr. Build. Mater. 416, 135261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.135261 (2024).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.S.H.: Supervision, Conception and design, Analysis and interpretation of data, Investigation of study, writing—original draft, review & editing. A.T.A.: Investigation, Methodology, representation of data writing—original draft, review & editing, D.M.: Methodology, representation of data writing—original draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hashem, F.S., Salam, A.T.A. & Monir, D. Mechanical properties and durability of slag granite geopolymer cement incorporated zirconium aluminum layered double hydroxide. Sci Rep 15, 17824 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02052-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02052-5